Abstract

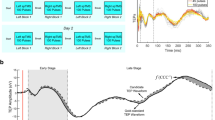

The strength of a given transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) pulse decays rapidly with distance. Male and female bone structure reliably differs by the shape of the frontal bone, mandible, and inion. Given the morphology of these structures constitutes much of the scalp-to-cortex distance (STCD), we hypothesized that females have shorter STCDs and thereby receive stronger TMS electrical field strengths, relative to males. Head models (n = 411; 197 female, 214 male) were constructed from MRIs of healthy participants (ages 18–90). STCD and peak electrical field strength were measured at 50 EEG 10–20 sites (SimNIBSv3.2). Linear models (bootstrapped and Benajamini-Hochberg multiple comparison-corrected) evaluated the influence of sex on STCD and electrical field strength. Females had significantly shorter STCDs at 27/50 sites and stronger TMS electrical fields at 18/50. When normalized by data collected at the motor cortex, females had significantly shorter STCD at 40/49 sites and stronger TMS electrical fields at 29/49 sites. The largest effect size differences were detected at the frontal, temporal, and occipital poles, and the cerebellum. Interestingly, STCD at the motor cortex was not different between sexes, suggesting the motor cortex-based dosing strategies produce unequal electrical fields between sexes. These data provide a mathematically grounded explanation for sex-differences in clinical outcome and may be relevant to other modalities that depend on electromagnetic signals (e.g., EEG, MEG).

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 13 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $19.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

MR images from the ADNI and ICBM data sets are publicly available. MR data from the Stanford data set can be made available upon request. Processed STCD and electrical field strength data for all data sets are available upon request.

References

Blumberger DM, Vila-Rodriguez F, Thorpe KE, Feffer K, Noda Y, Giacobbe P, et al. Effectiveness of theta burst versus high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with depression (THREE-D): a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1683–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30295-2.

O’Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, Sampson S, Isenberg KE, Nahas Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1208–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.018.

BrainsWay. BrainsWay Receives FDA Clearance for Smoking Addiction in Adults 2020. Available from: https://www.brainsway.com/news_events/brainsway-receives-fda-clearance-for-smoking-addiction-in-adults/.

Carmi L, Alyagon U, Barnea-Ygael N, Zohar J, Dar R, Zangen A. Clinical and electrophysiological outcomes of deep TMS over the medial prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices in OCD patients. Brain Stimul. 2018;11:158–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2017.09.004.

Zangen A, Moshe H, Martinez D, Barnea-Ygael N, Vapnik T, Bystritsky A, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for smoking cessation: a pivotal multicenter double-blind randomized controlled trial. World Psychiatry. 2021;20:397–404. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20905.

Huang Y-Z, Edwards MJ, Rounis E, Bhatia KP, Rothwell JC. Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron. 2005;45:201–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.033.

Pascual-Leone A, Valls-Sole J, Wassermann EM, Hallett M. Responses to rapid-rate transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human motor cortex. Brain. 1994;117:847–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/117.4.847.

Gamboa OL, Antal A, Moliadze V, Paulus W. Simply longer is not better: Reversal of theta burst after-effect with prolonged stimulation. Exp Brain Res. 2010;204:181–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-010-2293-4.

McCalley DM, Lench DH, Doolittle JD, Imperatore JP, Hoffman M, Hanlon CA. Determining the optimal pulse number for theta burst induced change in cortical excitability. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8726. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87916-2.

Nettekoven C, Volz LJ, Kutscha M, Pool EM, Rehme AK, Eickhoff SB, et al. Dose-dependent effects of theta burst rtms on cortical excitability and resting-state connectivity of the human motor system. J Neurosci. 2014;34:6849–59. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4993-13.2014.

Sackeim HA, Aaronson ST, Carpenter LL, Hutton TM, Mina M, Pages K, et al. Clinical outcomes in a large registry of patients with major depressive disorder treated with Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.005.

Hanlon CA, McCalley DM. Sex/gender as a factor that influences transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment outcome: three potential biological explanations. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:869070. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.869070.

Maxwell J. On physical lines of force. Philos Mag. 1861;1:451–513.

Bohning DE, Pecheny AP, Epstein CM, Speer AM, Vincent DJ, Dannels W, et al. Mapping transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) fields in vivo with MRI. Neuroreport. 1997;8:2535–8.

Luders E, Narr KL, Thompson PM, Rex DE, Jancke L, Steinmetz H, et al. Gender differences in cortical complexity. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:799–800. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1277.

Javaid Q, Usmani A. Anthropological significance of sexual dimorphism and the unique structural anatomy of the frontal sinuses: review of the available literature. J Pak Med Assoc. 2020;70:713–8. https://doi.org/10.5455/JPMA.32528.

Nambiar P, Naidu MDK, Subramaniam K. Anatomical variability of the frontal sinuses and their application in forensic identification. Clin Anat. 1999;12:16–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-2353. (1999)12:1<16::Aid-ca3>3.0.Co;2-d.

Lee MK, Sakai O, Spiegel JH. CT measurement of the frontal sinus - gender differences and implications for frontal cranioplasty. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2010;38:494–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2010.02.001.

Toledo Avelar LE, Cardoso MA, Santos Bordoni L, de Miranda Avelar L, de Miranda Avelar JV. Aging and Sexual Differences of the Human Skull. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:e1297 https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000001297.

Hanlon CA, Philip NS, Price RB, Bickel WK, Downar J. A case for the frontal pole as an empirically derived neuromodulation treatment target. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85:e13–e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.07.002.

Stokes MG, Chambers CD, Gould IC, Henderson TR, Janko NE, Allen NB, et al. Simple metric for scaling motor threshold based on scalp-cortex distance: application to studies using transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:4520–7. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00067.2005.

McCalley DM, Hanlon CA. Regionally specific gray matter volume is lower in alcohol use disorder: Implications for noninvasive brain stimulation treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021;45:1672–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14654.

Pitcher JB, Ogston KM, Miles TS. Age and sex differences in human motor cortex input-output characteristics. J Physiol. 2003;546:605–13. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029454.

Turco CV, Rehsi RS, Locke MB, Nelson AJ. Biological sex differences in afferent-mediated inhibition of motor responses evoked by TMS. Brain Res. 2021;1771:147657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2021.147657.

Lefebvre-Demers M, Doyon N, Fecteau S. Non-invasive neuromodulation for tinnitus: A meta-analysis and modeling studies. Brain Stimul. 2021;14:113–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2020.11.014.

McCalley DMHCA, Giardino WJ, McNerney MW, Padula CB, editor. Females Experience Greater Clinical Benefit from TMS to AUD: A Translational Analysis of Sex-Differences in Preclinical and Clinical Treatment Outcomes. American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; 2024; Phoenix, Arizona: Springer Nature.

McCalley DM, Kaur N, Wolf JP, Contreras IE, Book SW, Smith JP, et al. Medial prefrontal cortex theta burst stimulation improves treatment outcomes in alcohol use disorder: a double-blind, sham-controlled neuroimaging study. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsgos.2022.03.002.

MacNiven KH, Jensen ELS, Borg N, Padula CB, Humphreys K, Knutson B. Association of neural responses to drug cues with subsequent relapse to stimulant use. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e186466 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6466. Epub 2019/01/16PubMed PMID: 30646331; PMCID: PMC6324538 Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research & Development during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

Tisdall L, MacNiven KH, Padula CB, Leong JK, Knutson B. Brain tract structure predicts relapse to stimulant drug use. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119:e2116703119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116703119.

Mortazavi L, MacNiven KH, Knutson B. Blunted neurobehavioral loss anticipation predicts relapse to stimulant drug use. Biol Psychiatry. 2024;95:256–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2023.07.020.

Jack CR Jr., Bernstein MA, Fox NC, Thompson P, Alexander G, Harvey D, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): MRI methods. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27:685–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.21049.

Jack CR Jr., Bernstein MA, Borowski BJ, Gunter JL, Fox NC, Thompson PM, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Update on the magnetic resonance imaging core of the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6:212–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.004.

Mazziotta J, Toga A, Evans A, Fox P, Lancaster J, Zilles K, et al. A probabilistic atlas and reference system for the human brain: International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM). Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:1293–322. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2001.0915.

W Penny KF, J Ashburner, S Kiebel, T Nicols. Statistical Parametric Mapping: The Analysis of Functional Brain Images. London, UK: Elsevier; 2007.

Gaser CDR CAT - A Computational Anatomy Toolbox for the Analysis of Structural MRI Data. Organization for Human Brain Mapping. 2016.

Geuzaine C, Remacle J-F. Gmsh: A 3-D finite element mesh generator with built-in pre- and post-processing facilities. Int J Numer Methods Eng. 2009;79:1309–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/nme.2579.

Nielsen JD, Madsen KH, Puonti O, Siebner HR, Bauer C, Madsen CG, et al. Automatic skull segmentation from MR images for realistic volume conductor models of the head: Assessment of the state-of-the-art. Neuroimage. 2018;174:587–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.03.001.

Padula CB, McCalley DM, Tenekedjieva LT, MacNiven K, Rauch A, Morales JM, et al. A pilot, randomized clinical trial: left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex intermittent theta burst stimulation improves treatment outcomes in veterans with alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res (Hoboken). 2024;48:164–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.15224.

McCalley DM, Kinney KR, Kaur N, Wolf JP, Contreras IE, Smith JP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of medial prefrontal cortex theta burst stimulation for cocaine use disorder: a three-month feasibility and brain target engagement study. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2024.11.022.

McCalley DM, Hanlon CA. The importance of overlap: A retrospective analysis of electrical field maps, alcohol cue-reactivity patterns, and treatment outcomes for alcohol use disorder. Brain Stimul. 2023;16:724–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2023.04.015.

Thielscher A, Antunes, A, Saturnino, GB, editor. Field modeling for transcranial magnetic stimulation: a useful tool to understand the physiological effects of TMS? IEEE EMBS; 2015; Milano, Italy.

Jurcak V, Tsuzuki D, Dan I. 10/20, 10/10, and 10/5 systems revisited: their validity as relative head-surface-based positioning systems. Neuroimage. 2007;34:1600–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.024.

Opitz A, Windhoff M, Heidemann RM, Turner R, Thielscher A. How the brain tissue shapes the electric field induced by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neuroimage. 2011;58:849–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.069.

Nahas Z, Teneback CC, Kozel A, Speer AM, DeBrux C, Molloy M, et al. Brain effects of TMS delivered over prefrontal cortex in depressed adults: role of stimulation frequency and coil-cortex distance. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13:459–70. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.13.4.459.

Kozel FA, Nahas Z, deBrux C, Molloy M, Lorberbaum JP, Bohning D, et al. How coil-cortex distance relates to age, motor threshold, and antidepressant response to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12:376–84. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.12.3.376.

Nathou C, Simon G, Dollfus S, Etard O. Cortical anatomical variations and efficacy of rTMS in the treatment of auditory hallucinations. Brain Stimul. 2015;8:1162–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2015.06.002.

Hanlon CA, Lench DH, Dowdle LT, Ramos TK. Neural architecture influences rTMS-induced functional change: a DTI and FMRI study of cue-reactivity modulation in alcohol users. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019. Epub 2019/06/18. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.1545. PubMed PMID: 31206172.

Kedzior KK, Azorina V, Reitz SK. More female patients and fewer stimuli per session are associated with the short-term antidepressant properties of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): a meta-analysis of 54 sham-controlled studies published between 1997-2013. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:727–56. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S58405.

McCalley DM, Sanderson LL, Dowdle LT, Padula CB, Siddiqi SH, Ellard KK, et al. Illuminating posterior targets for transcranial magnetic stimulation beyond the prefrontal cortex. Nat Ment Health. 2025;3:859–69. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00433-3.

Lisanby SH, Husain MM, Rosenquist PB, Maixner D, Gutierrez R, Krystal A, et al. Daily left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: clinical predictors of outcome in a multisite, randomized controlled clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:522–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2008.118.

Feyrer A, Kerkel K, Mlcochova E, Langguth B, Schecklmann M. No sex difference in the antidepressive effect of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS): results from a retrospective analysis of a large real-world sample. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2025;26:170–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2025.2488357.

Fitzgerald PB. Targeting repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in depression: do we really know what we are stimulating and how best to do it?. Brain Stimul. 2021;14:730–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2021.04.018.

Stokes MG, Chambers CD, Gould IC, English T, McNaught E, McDonald O, et al. Distance-adjusted motor threshold for transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:1617–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2007.04.004.

Cave AE, Barry RJ. Sex differences in resting EEG in healthy young adults. Int J Psychophysiol. 2021;161:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2021.01.008.

Ott LR, Penhale SH, Taylor BK, Lew BJ, Wang YP, Calhoun VD, et al. Spontaneous cortical MEG activity undergoes unique age- and sex-related changes during the transition to adolescence. Neuroimage. 2021;244:118552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118552.

Shumbayawonda E, Abasolo D, Lopez-Sanz D, Bruna R, Maestu F, Fernandez A. Sex differences in the complexity of healthy older adults’ magnetoencephalograms. Entropy (Basel). 2019;21. https://doi.org/10.3390/e21080798.

Baker JM, Liu N, Cui X, Vrticka P, Saggar M, Hosseini SM, et al. Sex differences in neural and behavioral signatures of cooperation revealed by fNIRS hyperscanning. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26492. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26492.

Duffy KA, Epperson CN. Evaluating the evidence for sex differences: a scoping review of human neuroimaging in psychopharmacology research. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47:430–43. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-021-01162-8.

Van Hoornweder S, Nuyts M, Frieske J, Verstraelen S, Meesen RLJ, Caulfield KA. Outcome measures for electric field modeling in tES and TMS: A systematic review and large-scale modeling study. Neuroimage. 2023;281:120379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2023.120379.

Acknowledgements

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf. Data were collected for this manuscript from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number Q81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Heathcare;IXICO Ltd.; Jannsen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co, Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. Data were also collected from the International Consortium of Brain Mapping (ICBM). The ICBM project (Principal Investigator John Mazziotta, M.D., University of California, Los Angeles) is supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and BioEngineering. ICBM is the result of efforts of co-investigators from UCLA, Montreal Neurologic Institute, University of Texas at San Antonia, and the Institute of Medicine, Juelich/Heinrich Heine University, Germany. This work was supported by the Stanford Neurochoice initiative and the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (McCalley, K99AA031508).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

DMM and CBP were responsible for experimental design, data analysis, interpretation, manuscript writing, funding acquisition, and data collection. NJC, FW, and L-TT contributed meaningfully to data analysis and interpretation as well as data collection. BK contributed to data analysis, collection, and interpretation, as well as manuscript writing. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript in full prior to submission for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

*Affiliations listed within hyperlink: https://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

McCalley, D.M., Cadicamo, N.J., Weijerman, F. et al. Females have shorter scalp-to-cortex distances and receive stronger TMS electrical fields: Implications for clinical treatment. Neuropsychopharmacol. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-025-02299-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-025-02299-6