Abstract

Interest in psychedelic therapies is booming, with hundreds of studies in process. Despite the interest, there are no approved psychedelic treatments for any psychiatric condition. Further, the one large-scale development program using MDMA that reached the FDA was disapproved by the agency for reasons that could apply to clinical trials for classical psychedelics. We review the definitions of psychedelics, the current status of psychedelic therapies, conditions targeted, compounds under investigation, and the research/clinical strategies employed. Some treatment interventions include pharmacologically assisted psychotherapy, with both benefits and challenges associated with this strategy. There is debate about whether the psychedelic experience is a required fundamental element for therapeutic potential with the induced psychedelic state, rendering blinded clinical trials challenging. We address current societal issues, such as the deregulation of formerly illegal substances in some areas, that may affect development decisions. Our review also considers regulatory issues, including alternatives to blinded trials and whether some therapeutic targets, such as adjustment disorder, may pose hurdles if current regulatory standards are applied to these trials. The interest in psychedelic treatment is considerable, although the path forward has some complexities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mainstream interest in psychedelic therapies for the treatment of psychiatric conditions is booming [1], which reflects a return to interests originating decades ago. Psychedelic compounds have been tested for therapeutic use for a multitude of conditions [2], with an explosion of mainstream clinical research efforts. The convergence between the serotonergic mechanisms of classical psychedelics (psilocybin, LSD, Mescaline, and dimethyltryptamine (DMT)) and existing treatment agents used for mood and anxiety disorders may suggest a fortuitous path for reducing poor treatment response in a variety of conditions [3]. As current treatments are inarguably only partially successful for many conditions, including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety disorders, an alternative approach offering expanded benefits and more flexible and patient-friendly dosing compared to current approaches is likely to be embraced with sufficient evidence of efficacy. Further, there are several medications beyond the classical serotonergic psychedelics with alternative mechanisms of action, including glutamatergic [Ketamine and derivatives] and dopaminergic [MDMA: ±3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine]. These compounds are also under investigation for similar conditions [4].

Inherent in any consideration of treatment with psychedelics is the need for a safety discussion. Safety concerns for these currently restricted compounds include immediate medical adverse events (AEs), persisting AEs, and abuse potential. Such issues need to be considered first for participants in clinical trials and later during the period of approved use of these compounds. The diversion of FDA-approved opiate medications changed the landscape of substance abuse in America. The availability of approved, insurance-reimbursed psychedelic treatments will lead to a role shift for psychiatrists, who have commonly had to convince their patients to accept medications that were offered to them and will now have to act in a gatekeeper role.

Clinical and scientific issues

There are several current strategies for therapeutic uses of psychedelic medications, which we describe and review. The evidence for previous benefits of psychedelic treatments across strategies will be considered, along with the quality of the evidence. Some of the therapeutic approaches are designed such that psychedelic medications are used as adjuncts to psychotherapy [5], although this is not always the case [6]. In that context, the efficacy of the combined interventions needs to be differentiated from that of the components alone and to be practical and accessible. Another important issue is dosing and delivery. Some of these treatments are being investigated as a single-dose or single-day dosing [7,8,9], which requires understanding the durability of effects [10]. If the therapeutic effect is time-limited, redosing strategies need to be evaluated. Are there post-dosing interventions offered to “stretch” the benefit of the pharmacological psychedelic intervention [11], and how are they delivered and regulated?

Definitions of treatment targets are important for regulatory considerations. The FDA has granted breakthrough designation for trials on several well-defined clinical targets, including MDMA for PTSD, LSD for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression (TRD). There are trials currently targeting other less well-defined conditions, such as demoralization disorder, adjustment disorder to life-threatening illness, and combined conditions such as depression and PTSD or Alzheimer’s disease (AD) with anxiety. Historically, targets such as these have led to quite complex and challenging trial design proposals on the part of regulators.

Also important to consider during development and later clinical utilization is the history of previous experience with psychedelics on the part of treatment-seeking individuals. There are several factors of importance, including valence of previous experiences, expectation for therapeutic effect, potential to recognize a psychedelic effect when a clinical trial participant, and the motivation for seeking treatment: (drug seeking or depression?). In terms of the clinical applications of these compounds, there will likely be an ongoing dialogue about how many people seeking psychedelic therapies are in search of recreational substances.

There are multiple regulatory issues associated with the approval of psychedelic therapeutic uses that will be considered. Research designs have unique challenges because the core features of the psychedelic experiences are challenging to mask in a blinded controlled trial [12]. Most of these medications are legally prohibited from use [13], and all potential studies must navigate the legality of the acquisition and administration of the investigational products. There are many constituencies in the mix regarding regulatory decisions, including pharmaceutical companies that are seeking formal approval, government regulatory agencies, advocacy groups aligned on both sides of the clinical treatment and unregulated access issues, and political and legal systems. The safety of psychedelics in special populations is also critical, including participants with histories of psychosis or bipolar disorder [14]. Limited data are available on older populations as well, with as few as 2% of participants in published research studies to date being older than 60 [15]. Figure 1 depicts the three-dimensional model of legalities of use of these agents at the present time. This is a very useful conception and addresses multiple considerations. We present additional commentary on these considerations later.

Defining psychedelic drugs

Psychedelic medications are defined by their psychological effects after administration. These include multiple experiences, clearly articulated by Fonzo et al. [2], including “alterations in emotional processing; alterations in sense of self; changes in sensory perception (including visual and auditory illusions, distortions, and/or hallucinations); psychomotor slowing; shifts in attention, working memory, and executive function; and, at times, profound states of consciousness, termed ‘mystical experiences’, characterized by a sense of unity, ineffability, and deep reverence for life, oneself, and the world.” These experiences are common, with some degree of uniformity, with dosing of classical psychedelics, and there are rating scales developed to measure their occurrence (The 5-Dimensional Altered States of Consciousness Rating scale; [16]). These same experiences are also described as an experiential feature for some subset of individuals exposed to the dissociative anesthetic ketamine and its variant, esketamine [17,18,19].

Classical psychedelic drugs are agonists at the serotonin 2A receptor [20]. These drugs include LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin, as well as some more short/rapid-acting compounds such as dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and 5-methoxy-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT [21, 22]). These drugs have multiple downstream effects, but their interaction with serotonin 2A may be central to their potential benefits for psychiatric disorders. One of the suggested benefits of these treatments is induction of neuroplasticity [23], the time course and extent of which is not well-defined. DMT and 5-MeO-DMT have been proposed to have unique benefits because of their rapid onset and offset, allowing for shorter therapeutic sessions. The psychedelic effects of oral psilocybin or LSD have a 30–60 min onset time and last 4–6 h [24], those of inhaled 5-MeO-DMT and intravenous DMT occur instantly and potentially only last for 15–30 min [25]. Thus, the time frame of intervention sessions varies considerably across the compounds, possibly impacting on cost and practicality of therapeutic interventions.

The effects of MDMA do not seem to be psychedelic-like, without depersonalization or derealization or the visual perceptual phenomena and panic reactions that are associated with classical psychedelics, instead producing a state of positive mood and correlates as described below. MDMA is commonly discussed as a psychedelic drug, but its mechanism of action is not directly serotonergic but rather stimulant-like. The resulting state of positive mood, subjective well-being, and extroversion, including increased sensitivity to environmental cues [26], has led to its description as an “empathogen” or “enactogen.” Effects of MDMA, in contrast to classical psychedelics, are not attenuated by blockade of the serotonin 2A/C receptors by ketanserin [27]. Further, in a comparative study examining subjective effects in healthy individuals of different medications, including MDMA, LSD, and amphetamine, MDMA was reported to have subjective effects similar to amphetamine and distinct from LSD [28].

We focus our review on the classical psychedelics, including newly developing variants, with discussion of MDMA because of its wide interest as a psychotherapy adjunct, but do not review efficacy and clinical uses of the dissociative anesthetic compounds ketamine, phencyclidine, and the ketamine derivative esketamine. The use of these compounds has been systematically and recently reviewed elsewhere [29, 30]. There are some relevant features of these compounds in terms of designs for clinical trials with psychedelics, including consideration of active placebos to control for strong subjective effects, the potential association between dissociative effects and antidepressant efficacy, and uses in special populations such as children.

Cannabis is also not considered to be psychedelic. It can cause transitory dissociation in some individuals, and it clearly increases the risk for psychosis in a subset of users [31], with even higher risks in individuals at high risk for psychotic disorders [32]. Cannabis interacts with the cannabinoid receptor and not the serotonin (or dopaminergic) receptor system. Thus, the potential benefits of psychedelics in terms of their serotonergic interactions are absent for cannabis, and we focus our discussion on these other compounds. As with the NMDAR agents described above, we consider some potential cannabis use cases for refinement of clinical trials with psychedelics.

What are the target conditions for psychedelic treatment?

There are a host of conditions that have been identified recently as potential targets for psychedelic treatment, with the number and quality of the treatment efforts to date varying considerably across targets. Esketamine is a non-antidepressant FDA-approved treatment for TRD, and there are multiple studies targeting TRD as well as suicidal ideation in depression. Many studies of psychedelics have targeted TRD as well, but there are multiple other conditions that have been targeted in one or more studies. We organize our discussion by condition and detail the treatment efforts across psychedelics. Further, as there are so many treatment efforts underway, we refer the reader to a continuously updated source for all efforts and focus our attention on completed phase 2 and 3 trials, both successful and unsuccessful.

A primary source for this development information is the “Alpha Bullseye Chart,” which is an updated tracker of all known research efforts in psychedelic treatment: psychedelicalpha.com/news/q125-psychedelic-drug-development-pipeline-bullseye-chart. This website compiles all current clinicaltrials.gov registered trials at FDA phases 1,2, and 3 for all medications defined by the organization as psychedelic (which includes MDMA and ketamine and variants). The remarkable number of different conditions being treated with psychedelics is highlighted by the summary generated by Fonzo and Nemeroff [4] from this chart. There were 14 phase 2 trials with psilocybin alone and 12 using other psychedelics. There were also a total of 24 phase 1 trials. It would not be possible to describe all of these trials, but some of these phase 2 trials will likely transition to phase 3 because of the considerable financial support and enthusiasm for these efforts.

Major depression and treatment-resistant depression (TRD)

Major depression and TRD reflect the most common treatment targets for psychedelic therapy. There are two US-registered phase 3 trials ongoing, with the most advanced being studies of psilocybin for adjunctive psychotherapeutic treatment of TRD and Deuterated psilocybin for MDD. The adjunctive psychotherapy study uses the Compass Psychological Support Model [33] and psilocybin treatment. This study is a follow-up of a longitudinal randomized 12-month study comparing 1 mg, 10 mg, and 25 mg single doses of psilocybin [7]. In the previous study, 25 mg doses provided a greater sustained benefit than 1 and 10 mg doses over the 12-month follow-up [10].

A very recent press release reported top-line results of this study [https://ir.compasspathways.com/News-Events-/news/news-details/2025/Compass-Pathways-Successfully-Achieves-Primary-Endpoint-in-First-Phase-3-Trial-Evaluating-COMP360-Psilocybin-for-Treatment-Resistant-Depression/default.aspx]. Active treatment augmentation of psychotherapeutic interventions was superior to placebo augmentation by 3.6 points on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS [34]). There were no differences in suicidal ideation between treatment arms. The full results are pending, but this difference was statistically significant. The clinical significance of this improvement needs to be considered in the context of the severe TRD status of participants on the one hand and the substantial investment of time and effort in the treatment on the other. The cost-benefit of this treatment will need to be evaluated.

A phase 2 study with psilocybin and psychosocial intervention was recently published [35], comparing a single 25 mg. dose of psilocybin to a 100 mg niacin comparator, combined with supportive treatments. The outcomes of the study suggested that both depression and self-reported functioning were superior with active treatment at 43 days. There were more AEs with active treatment. There was no attempt to assess functional unblinding, but the clinical ratings were conducted by remote raters.

There are also two phase 3 trials with an LSD variant, lysergide-D-tartarate (MM120), delivered in a rapid dissolving formulation (Mind Medicine, Inc.) in the treatment of MDD. The first study launched on April 15, 2025 [36]. As presented in a press release, the first study, 52-week program called “Emerge” study, will be conducted in two parts: Part A, a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study assessing the efficacy and safety of a single dose of MM120 ODT versus placebo; and Part B, a 40-week extension period during which participants will be eligible for open-label treatment with MM120 ODT based on symptom severity. In Part A, participants will be randomized 1:1 to receive MM120 ODT 100 µg or placebo. The primary endpoint of Emerge is the change from baseline in MADRS score at week 6 between MM120 ODT 100 µg and placebo. These studies use sophisticated strategies for the clinical ratings, including remote raters and high levels of training and supervision for in-person raters.

There are multiple phase 2 studies of TRD and MDD in process with other compounds, including DMT, LSD, and MDMA, as well as other treatments characterized as “miscellaneous.” In psychiatric drug development, there have been notable challenges with sustained success in the transition from phase 2 trials to phase 3. Clearly, there will be a substantial burst of information coming soon as these trials are completed.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

PTSD is another common treatment target for psychedelic therapy. It shares challenges in the efficacy of pharmacological treatments with TRD, with many participants poorly responsive to previous medication treatments. There have been multiple previous studies of medication-assisted psychotherapy in PTSD, with a detailed review presented by Wolfgang et al. [37]. There have been at least 8 randomized, placebo-controlled trials of MDMA assisted therapy at the phase 2 or phase 3 levels, with the majority presenting quite positive results. The most advanced development program of MDMA for PTSD is the Lykos psychedelic-assisted therapy study, which advanced all the way to a US FDA advisory panel. This program included a positive phase three study [38], which randomized 90 patients 1 to 1 to receive manualized therapy accompanied by a placebo or by psilocybin. The authors reported a substantial separation of active and placebo-treated psychotherapy groups on the primary outcome, improvement in the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5 [39]). This study was followed by a similarly designed, slightly larger phase 3 study [40], where 104 participants were randomized to similar treatment strategies, with similar results and reports of separation of active and placebo treatment groups. The FDA advisory panel meeting on June 4, 2024 [41] turned down the application and raised several questions about the conduct of the study [42]. These include functional unblinding, therapist misconduct, and contribution to unblinding, and prior exposure to psychedelics on the part of a substantial number of the trial participants.

In a very unique observational study, Cherian et al. [43] administered ibogaine in an open-label study to 30 special operations veterans and examined several outcomes, including PTSD. Significant changes in depression, anxiety, and PTSD were identified, as were significant improvements in self-reported everyday disability. As noted by the authors, a blinded trial with broader outcomes assessments is certainly important, and consideration of the potential cardiac AEs of ibogaine will remain critical.

In addition to pharmaceutical industry efforts, psychedelic treatments, particularly MDMA, are in wide use in the veteran populations with PTSD [44]. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) established a formal structure and process for the examination of the potential for psychedelic treatments, which led to a report [45] and a request for applications to develop interventions [46]. Several areas of special consideration are present for veterans, including the very high prevalence and severity of PTSD seen and the intrinsically limited resources of the VA [47]. These VA efforts are proceeding in parallel with drug development efforts from pharmaceutical companies seeking FDA approval. Given the interest in innovative treatments for PTSD and the potential to improve the design of some of these treatment efforts, it seems likely that PTSD treatment with psychedelics will continue to be robustly pursued. Like TRD and MDD, a burst of results is to be anticipated, although it is completely clear how many of these studies would meet regulatory standards for a registration trial.

Anxiety disorders

GAD is being studied in two phase 3 trials with an LSD variant, lysergide-D-tartarate (MM120), delivered in a rapid dissolving formulation and conducted by the same company, Mind Medicine, Inc., as the above-described MDD trials. Both are single-dose studies. Previous dose finding studies settled on doses of 50 and 100 μg and placebo that are administered after randomization, with a 12-week in-study follow-up period and a 40-week extension study to examine the durability of the effects. Outcomes include clinical ratings of anxiety and depression and safety data.

There are multiple phase 2 studies on GAD listed in the tracker. These include interventions using 5-MeO-DMT, psilocybin, MDMA, and DMT. Clearly, there will be a flood of results in these areas in the near future, and it will be very important to see which of the treatments will be successful. Multiple previous studies have been conducted, but some included participants who had anxiety that did not meet GAD criteria. In fact, these studies were characterized by reviewers as having methodological challenges, nonstandard dosing, and short follow-up periods [48].

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) and other forms of substance abuse

There are two phase 2 AUD studies listed with psychedelic treatments, including interventions using psilocybin and 5-MeO-DMT. Several phase 1 studies are listed, including the only company officially testing interventions with mescaline. Finally, there is a phase 2 opiate use disorder study listed, testing the use of IV ibogaine as the intervention.

In an interesting non-registration trial of psilocybin for AUD, active treatment vs placebo was combined with 12 weekly psychotherapy sessions, with the outcomes being impact on personality factors and subsequent alcohol use [49]. Several dimensions of personality functioning changed more in the active treatment group, including reductions in neuroticism and increases in extraversion and openness. Across both groups, decreases in impulsiveness were associated with lower posttreatment alcohol consumption. Exploratory analyses revealed that these associations were strongest among psilocybin-treated participants who continued moderate- or high-risk drinking prior to the first medication session. A challenge in the study results was that the 4-week psychotherapy run-in was associated with substantial improvements in drinking, such that only a subset of the participants (17/44) randomized to psilocybin manifested moderate or higher alcohol risk scores after 4 weeks of psychotherapy. Despite the reduced sample size, the correlations between changes in drinking and changes in personality factors in psilocybin-treated participants were substantial, r = 0.50 for all 17 participants and r = 0.70 for the 11 participants whose risk score was high or very high at week 4.

Adjustment to serious illness

An additional clinical topic covered by some psychedelic treatment studies is that of adjustment disorders induced by serious or life-threatening illness. The roadmap indicates that there is a study on the use of LSD as a treatment for existential distress in cancer patients and a phase 1 study on the use of 5-MeO-DMT to treat depression in AD. Further, there is a phase 2 study by Reunion Neurosciences using injected psilocybin as a treatment for adjustment disorder associated with life-threatening illness. These are clearly areas of need, and there are potential regulatory challenges associated with the treatment of adjustment disorders, in terms of defining treatment targets and addressing consent and safety issues. It is unclear if regulators will view adjustment disorders to multiple medical illnesses as fundamentally similar or if there will be strict operationalism. Historically, it would not be surprising to receive the regulatory suggestion that adjustment disorder in response to breast cancer has to be addressed in completely separate studies from adjustment disorder in response to lung cancer.

Other conditions and considerations

There are several other conditions with registration trials and with non-registration research in process. These include obsessive-compulsive disorder, tobacco dependence, demoralization in long-term male survivors of AIDS, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, as well as anorexia nervosa and treatment-resistant body dysmorphic disorder [2]. Some of these targets are clearly defined in the DSM, and for those pre-defined disorders, the regulatory question will be limited to whether psychedelics provide a path forward for treatment in these conditions, where there are very few current treatment options.

Another topic of considerable clinical importance is the utilization of psychedelics in older individuals. Some of the psychedelic treatment targets currently under investigation are directly related to aging, such as depression in AD. Other aging-related considerations fall in line with the common treatment targets in younger individuals. These included the increased prevalence of TRD in older individuals, based on the tendency for depression to be more common [50] and less responsive to traditional treatments [51] in this age group. As many as 1/3 of older people experience depression, and older people with TRD may represent close to a third of all TRD cases in the US [52]. This would seem to suggest that psychedelic treatment might be a reasonable suggestion [53]. Despite the apparent need, fewer than 2% of all participants in previous psilocybin treatment trials have been over the age of 65 [15]. Despite medical considerations in older populations, a clear cost-benefit analysis can be performed, and the morbidity (and suicide related mortality) associated with TRD in older populations needs to be considered.

There are other conditions, such as prolonged grief disorder (PGD), which is clearly common in the elderly because of their life stage. This condition, recently defined in diagnostic manuals, consists of a grief reaction that is longer and often more intense than the norm, which is associated with multiple morbidities [54]. It has been suggested that PGD could be a prime treatment target for psychedelics [55] because of the potential for the directly relevant benefits from psychedelic experiences, which are marked by transcendence, mystical experiences, and a sense of oneness, to directly counteract the existential distress associated with bereavement. An open-label feasibility trial is currently underway to address this strategy and target [56].

Table 1 presents a summary table for the conditions currently being considered for psychedelic treatment. We present the conditions in terms of their presence in existing diagnostic systems, with primary conditions separated from co-morbid conditions or treatment of a subset of targeted illness features. We include TRD as an illness feature target because the diagnostic systems do not specify a definition of TRD, and each study sponsor will have to achieve regulatory consensus regarding their definitions.

Dosing strategies

Several strategies for dosing psychedelics are being investigated and will have implications for the clinical uses of these treatments. Across all medication treatment strategies, there is commonly a time-linked treatment target, which varies as a function of at least three different mechanisms of influence of treatments on psychiatric conditions shown in Box 1.

Antipsychotic and antidepressant medications are an example of the first case, while single-dose therapeutics such as psychedelics are an example of the second. Cancer immunotherapy is an example of the third. For the first use case, daily dosing is central to the use of the medications, which is commonly one or more times per day, other than long-acting formulations. For the second use case, the time to recurrence of symptoms would determine redosing schedules. The third use case seems rare in psychiatry, but medication-assisted psychotherapy could be seen to have a cure as a goal.

In the MDMA assisted therapy studies that formed the basis of the Lykos FDA application, there were three dosing periods accompanied by concurrent therapy, with these periods separated by a month or so. Dosing was escalated in participants who could tolerate the medication. Other treatments, including psilocybin, LSD, and DMT, have often been dosed once, although there are clinical trials that used multiple doses. A meta-analysis suggests that multi-dosing of psilocybin had greater efficacy than a single dose for sustained treatment of depression [57]. The ongoing Mind Medicine 12-month LSD studies for GAD and MDD involve plans for redosing during the 12-month extension period at time periods to be determined by clinical need. These data highlight the open questions for clinical uses of psychedelics that will need to be answered with post-registration research. If a drug has a long-term beneficial effect, its durability needs to be determined to identify when re-treatment is required. If re-treatment is required, the parameters of the re-treatment strategy will need to be determined: Repeat the initial dose, administer a larger dose (now that tolerability and efficacy are proven), or administer smaller doses, possibly more frequently?

There are a substantial number of conditions being considered for treatment with a limited set of psychedelic compounds. It thus seems likely that the duration of treatment benefits and required redosing may be both condition and compound-specific. If clinical benefits within a compound are fortuitously homogenous across conditions, then dosing strategies could converge as well.

Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy

As noted by McIntyre et al. [58], it has consistently been shown in the treatment of TRD that combined therapy with medication and carefully delivered and manualized psychotherapy has additional benefits. In the psychedelic arena, the concurrent application of psychotherapy and psychedelics is very common; a recent systematic review [59] reported on 45 studies assessing combined psychotherapy and psychedelics, including psilocybin, MDMA, LSD, or ayahuasca. Psychotherapeutic interventions ranged from coaching or support to manualized therapy. Application of a systematic rating system, the Template for Intervention Description and Replication [60] checklist, in that review led to a number of important findings. For studies with psilocybin, MDMA, and LSD, a three-phase therapy structure could be delineated: preparation, support, and integration, which suggests continuity over the course of treatment. However, limitations in the individual study reports included a general lack of reported information about fidelity of the therapists to the suggested therapies, as well as a lack of information about the professional credentials of the therapists in some studies. Studies using the MAPS manual and the COMPASS system were noted as being likely to promote potential replication in later studies. Consistent with the comments of McIntyre et al., the authors suggested that the design of the previous studies does not allow for the separation of the impacts of drug vs. the psychotherapeutic treatment in most cases. This would not be a clinical barrier but might pose a challenge for regulatory approval or eventual insurance payments.

The reaction of the US FDA to the Lykos studies is informative regarding the challenges to assisted therapies. The FDA decision included comments on the lack of a priori validation of the therapeutic intervention. The Seybert et al. review noted that the Lykos studies did not specify the credentials of the therapists, stating that at least one member of the therapy team had to be licensed locally to deliver psychotherapy, and a master’s degree was required. Training in the delivery of the intervention was well-described, but there were no reports in the papers of fidelity to the therapeutic strategies.

There are also questions about the feasibility and cost of psychedelic-assisted therapy. First, regulatory agencies are being asked to approve both a medication treatment and a psychotherapy. The previous Lykos decision suggests there will be ongoing concerns regarding the separability of medication and psychotherapeutic effects. Second, access may be limited, particularly for individuals who are disabled by long-term psychiatric issues such as TRD or PTSD. Payers are commonly reluctant to pay adequately for psychotherapy alone and are even less willing to pay for unlicensed providers. Many insurance plans cap the number of psychotherapy sessions allowed, and some of the current models have more psychotherapy visits than payers are willing to cover. This concern would be potentially reduced with institutional payers, such as the VA or national health service insurance plans, such as those in the UK or Canada. However, in the public sector in the United States, this would be a major concern. In the state of Florida, for instance, no outpatient services delivered by a psychologist are covered by Medicaid.

Safety

Dating back to the days of “Reefer Madness,” the general public perception has been that psychoactive substances carry unavoidable and catastrophic risks. As noted by multiple reviews of the safety of psychedelics in general [5] and in clinical trials [12], there are substantial differences between investigational products delivered in clinical trials and illicitly obtained psychedelics. A critical feature of these comparisons is that illicitly obtained psychedelic medications may be self-administered in conjunction with other substances. Further, adulterants potentially present in illicit medications are absent in investigational products. There are still legitimate concerns. Psychedelic compounds commonly have substantial serotonergic activity, and serotonin-related conditions could be a risk linked to classical psychedelics across uses [61, 62]. Psychedelics are well known to increase blood pressure, raising the risk of stroke in patients with pre-existing hypertension. Ghaznavi et al. [63] review the medical safety of psychedelics and conclude that cardiac events are quite rare but could be detected in small numbers of individuals with identifiable pre-existing risk factors.

Another issue is that there are several syndromes reported in individuals with regular psychedelic use, and if these originate from the psychedelic compounds, they could occur in study participants and in clinical treatment. Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) is one such syndrome, which is differentially persistent and may be exaggerated in individuals with other psychiatric conditions [64]. As the prevalence of HPPD is not well understood, and case control evidence is lacking, although the number of cases of HPPD seems small given the population’s exposure to psychedelics [65]. This is certain to be a safety issue requiring close monitoring.

Is a psychedelic experience required for treatment efficacy?

There is a major controversy regarding the psychedelic experience as a prerequisite for therapeutic efficacy. A number of scientists [66,67,68] have argued that the gains from treatment are intrinsically correlated with the intensity of the psychedelic experience. Some are not convinced [69]. An excellent example is the study of Aaronson et al. [70]. In that study, 12 participants with severe TRD were treated in an open trial of psilocybin with psychotherapeutic support delivered by clinicians trained in the COMPASS protocol. In an exploratory analysis, the authors reported that the occurrence and intensity of the psychedelic experience of “oceanic boundlessness” indexed by the Five Dimension Altered State of Consciousness Scale (5D-ASC [71]) was correlated with the extent of antidepressant response. This same design was used in a study of treatment-resistant bipolar depression by the same research group [72]. Again, the intensity of psychedelic experiences was correlated with the extent of antidepressant response from psilocybin.

Mystical experiences are reported across all psychedelics. Interestingly, a recent study suggested that high doses of cannabis can induce similar experiences [73], including the oceanic boundlessness experience. The rate of psychedelic experience (20%) was about 1/3 of that previously reported in psilocybin trials, and individuals with more cannabis experience reported reduced psychedelic experiences. Another study of cannabis [74] found that cannabis doses of 7.5 to 15 mg of oral THC lead to similar changes in language entropy compared to those previously reported with LSD [75]. Thus, some of the subjective and observable features of psychedelics can appear with cannabis, suggesting that the need for understanding if mystical experiences are on their own or associated with the specific pharmacology of psychedelic treatments is the driver of these findings.

It has recently been argued [76] that it is possible to develop compounds that replicate the therapeutic benefits of classical psychedelics without the related psychedelic experience. These compounds are described as “plastogens” in that they promote the same postulated plasticity processes induced by current psychedelics. If this were to prove to be the case, many of the challenges associated with both clinical trial design and regulatory issues would be resolved. First, blinding would be easier. Second, safety concerns would be reduced, as abuse liability would seem to be limited by the lack of psychedelic effects. This possibility creates a real conundrum, because if regulators are unwilling to accept data from trials without unequivocal blinding, do we have to wait until the next generation of “non-psychedelic plastogens” work their way through all of the stages of FDA approval? This would be a very challenging position, because if their efficacy turns out to be less than the original compounds, then the wait would potentially be quite disruptive to the development effort.

Legal status of psychedelic distribution

As described in an excellent recent paper [13] on the legal status of psychedelic therapies, most of these compounds have extremely restricted access at present. There are several levels of registration and approval of potentially therapeutic medications, only some of which would involve the option to prescribe these medications, with reimbursement an even more distal goal. The very useful framework discusses therapeutic intent, legality, and structure. For instance, a medication that is approved by the FDA for prescription by physicians for a specific condition, manufactured under supervision, and dispensed by a registered pharmacy would have the highest levels of all three constructs. Illicit purchase for non-therapeutic personal use would be the lowest. Therapeutic intent is likely challenging to measure because it seems likely that a considerable number of participants who receive medicinal cannabis are not using it for therapeutic purposes. Legality is higher for the regulated dispensing of medicinal cannabis than for legalized or decriminalized recreational use, and the overall level of structure decreases from a prescription for a specific condition to generalized medicinal use, and then recreational use. Drugs purchased from a dispensary with regulated products would be more structured and more legal than illicit purchases.

Current levels of regulation

The existing hierarchy of regulation for restricted compounds is in flux due to the decriminalization of cannabis [77]. In a modification of the Kian conception, we present the hierarchy of regulation of all formerly restricted psychoactive drugs in Box 2.

This hierarchy can be mapped onto cannabis and, now, to psilocybin in some locations [78]. There are 24 states in the US where personal cannabis possession has been explicitly legalized. Cannabis possession in many other localities is not the subject of law enforcement, making it unregulated on a de facto basis [79]. In those de facto situations, the origin of the cannabis and its quality and safety (i.e., is it adulterant-free?) are not under government supervision in most cases. In the case of medical cannabis, individuals can obtain and possess cannabis with a doctor’s order. In most locations, this is not equivalent to a prescription, but more like a permission slip. In many states, an eligibility card can be obtained, which allows for purchases of various products from legal dispensaries up to statutory limits. In most “medical cannabis” situations, insurance does not cover the cost, and there has been no formal regulatory process for the evaluation of the efficacy of medical cannabis. Safety is commonly evaluated by inspection standards for legal cannabis dispensaries. Although cannabis is still restricted by the Federal government, prosecution of individuals for cannabis possession is suspended as long as the individuals are complying with local laws.

A considerable volume of scientific literature also describes uses of psilocybin outside of formal clinical trials. For instance, Kettner et al. [15] presented data on responses to psilocybin in younger and older individuals who attended psychedelic retreats and used a variety of substances, typically psilocybin. Outcomes were collected by self-report, with structured assessment scales, and there were several findings reported. Included in the results were clinical responses on the part of individuals who self-reported having certain conditions (Depression, Anxiety) for which psilocybin is being tested as an intervention. However, the results did not originate from a clinical trial, and a substantial proportion of cases did not provide follow-up information. Information such as this would not be usable as evidence for an FDA approval, and the response rate might also be seen as a barrier. However, as we noted in a commentary [80], evidence from studies such as this could easily be presented to local government officials in support of the idea that individuals with these conditions could benefit from self-administered psilocybin. These data are at least as high quality as the research supporting medicinal cannabis use, and there are many similar observational studies in the literature.

In Oregon, psilocybin is now available under the same framework as medicinal cannabis in other states. There is some intermediate level of structure, because facilitators, service centers, manufacturers, and laboratories are under supervision, but there is no legally defined set of conditions to be treated. This development is quite interesting because there are a substantial number of conditions described above where psilocybin is under investigation under potentially FDA-regulated strategies. It is unclear what will happen in the eventuality that psilocybin consistently fails to separate from a placebo in clinical trials. Will the manufacturers seek to make these variants of psilocybin available in Oregon and other jurisdictions yet to come with similar access regulations? Will there be efforts to lobby for the expansion of similar access beyond Oregon? Will there be efforts on the part of developers of other medications, such as LSD, DMT, and mescaline, to seek their distribution there? Clearly, there are many constituencies that are convinced of the value of psychedelic therapy. What will happen if the FDA regulatory approval of these compounds is substantially delayed?

Interpretive concerns with psychedelic clinical trials

FDA or equivalent regulatory approvals consider both efficacy and safety. In the following sections, we consider challenges with the design and conduct of regulatory clinical trials and address some potential barriers if current regulatory standards are applied.

Blinding

Double blind randomized clinical trials presume unawareness of treatment status. However, psychedelics induce an experience in most recipients that may be challenging to mask. The majority of participants in trials of psilocybin and MDMA accurately identified their treatment condition [38, 81]. As noted by McIntyre et al. [12], not only can awareness of treatment assignment exaggerate perceived benefits but could potentially lead to negative (i.e., “Nocebo”) responses on the part of participants who become aware that they are not receiving active treatment.

Given the many challenges with inactive placebos [82], active placebos or dose-response study designs have been suggested. This challenge was recognized early on in studies of ketamine, where active placebo conditions have been attempted. Many studies have used midazolam as an active placebo, with results suggesting that the magnitude of ketamine effects is slightly different when compared to saline or midazolam [83] as the comparator treatment. Subsequent trials of the expansion of esketamine treatment to children have used that compound as well [84]. There is some limited evidence of reduced treatment separation, defined by the odds ratio for clinical response, of ketamine and midazolam (OR = 3.7), compared to ketamine compared to a saline control(OR = 2.2), either due to masking effects of midazolam preserving the blind or potential clinical benefits of midazolam. Further, suicidal ideation and depression symptoms have different levels of placebo response [85].

Active placebos have also been used in studies of psilocybin [35] and other compounds. A recent review provided systematic suggestions for strategies for choosing active placebos for psychedelic treatment [86]. Given the results of the ketamine studies described above, the effect of the treatment may be substantial across comparators. An additional strategy for comparators has been smaller or “micro-doses” of the active treatment as the control condition [87]. The logic is that a microdose is too low to produce efficacy, but that the low-level psychedelic might serve a masking function by being detectable to participants while lacking efficacy. A final suggestion is that of cannabis as an active placebo. As noted above [73], substantial single doses of cannabis can induce a full psychedelic experience in as many as 20% of cases. Aday et al. [86] suggested cannabis as a possible active placebo in single-dose psychedelic studies, because single doses of cannabis are not believed to have any therapeutic benefit for targeted conditions.

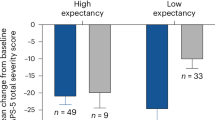

Another perspective is that of alternative control strategies [88]. These can include comparison with existing treatments, such as randomization to antidepressant or antipsychotic medications versus psychedelic treatment. It is not clear if either of these comparison strategies could aid in blinding. Another interesting suggestion was recently advanced, suggesting that expectancy effects could be measured as an individual difference variable and used as part of a covariate strategy to understand expectancies’ independent effects on treatment outcomes [89]. These are appealing strategies, but it is unclear what evidence would need to be produced in order to convince regulators that this is an effective control.

Previous history of psychedelic use

An issue in several previous psychedelic studies is the prior personal history of psychedelic exposure. In the Kettner et al. study, 44% of the older participants reported prior psychedelic experience, and 29% reported more than five previous uses. In the Lykos phase 3 studies 32% and 46% of the participants reported prior MDMA use. This is a multi-faceted problem. Can experienced participants be blinded? Are they in the study because of psychiatric symptoms or drug-seeking behavior? Clearly, having a large proportion of drug-experienced participants could compromise clinical trial design, and matching drug and placebo groups for prior experience could actually exacerbate challenges in blinding trials, because accurate recognition of both drug and placebo treatments would seem to be more common on the part of experienced participants.

Concurrent conditions: comorbidities and treatment of a limited set of illness features

Previous registration efforts to treat concurrent features of other diagnosable conditions have proven quite challenging. For instance, attempts to treat negative symptoms or cognition in schizophrenia have required complex designs [90,91,92], with multiple assessments to assess all features of the base condition (e.g., psychosis and negative symptoms for cognition studies and psychosis and cognition for negative symptoms studies) in order to prove the specificity of the treatment to the target outcome feature. A further regulatory concern has been whether other illness features are adversely affected by the novel treatment, even if the primary outcome is positive. The resulting design is cumbersome and can require a multi-day baseline assessment. The requirements of this design raise the bar considerably because it requires potentially complex assessments of the primary outcome, as well as the ancillary assessments.

Clearly, among the current group of developing psychedelic studies, registration trials for the treatment of depression in AD could be required to use similarly complex strategies to define the features of AD that are required to be present (as well as absent) in the study participants. Additional considerations would be the impacts of other treatments offered for AD, as there are multiple symptomatic and potentially disease-modifying treatments (cholinesterase inhibitors, memantine, and anti-amyloid treatments) that many patients would be expected to be receiving. It would not be a realistic regulatory suggestion to exclude all such treatments. Adjustment and mood symptoms in cancer seem to be similarly challenging in reference to outcomes induced by features of the illness vs. concurrent treatments (e.g., fatigue and cognitive changes). Clearly, relaxation of previous regulatory guidance would be required for these studies to be feasible and have any chance of a positive outcome.

Are we considering suggesting psychedelic treatments for children?

Several studies have reported on the use of both ketamine and esketamine in children with TRD and substantial suicidal ideation [84, 93, 94]. Also, other studies have reported on the psychedelic treatment of adults with disorders that generally originate in childhood, such as anorexia [95], ADHD [96], autism spectrum disorders [97], and body dysmorphic disorder [98]. While childhood TRD and suicidal ideation and behavior have all the features of a critical indication, what about the others? If anorexia could be reversed at age 14, its mortality would be notably decreased. If standard treatments for ADHD are either ineffective or intolerable in middle school, alternative treatments would seem to raise the chances of success in high school and college. LSD has been tested in ADHD, albeit without success [96]. Would we suggest psychedelic therapy in middle school for ADHD that fails to respond to state-of-the-art prodrug treatments, which is about 20–30% of cases [99]?

True risk-benefit is hard to estimate for many of these situations. However, if psychedelic drugs are approved for adults with a variety of conditions, the US FDA commonly requires studies in children as well. Informed consent and assent for research and subsequent parental consent for treatment, as well as vetting parents for appropriate motivation for their children’s treatment, reflect complex ethical issues that will require ongoing consideration at a level far beyond that required in previous expansions of approved drugs to childhood uses.

Conclusions and future research directions

Psychedelic treatments for mental health conditions are under investigation for a multitude of conditions across an array of psychedelic compounds across all stages of development (phases 1–3). Motivation to conduct these studies arises from the large proportion of participants who are not responsive to existing therapies. Certain subgroups, such as older individuals, more commonly manifest treatment failure compared to younger individuals. Many studies are also being conducted that are not officially supervised by regulatory agencies. These studies include monotherapy strategies as well as multiple studies aiming to augment the effects of an array of supportive and psychotherapeutic interventions.

Long-term concerns about the risks of psychedelics have historically led to legal prohibition. Data from supervised trials suggests that the safety risks seem lower, acutely and long-term, than illicit use. However, many studies have had limited safety assessments and limited long-term follow-up. Further, standard blinded trials are very difficult because psychedelic effects have made blinding challenging, and many participants are aware of their assigned treatment. The controversy about the need for a psychedelic experience is far from resolved, and medications are in development that aim to provide therapeutic efficacy without the psychedelic experience. These compounds would be promising for blinding trials, but these medications are years behind existing compounds in their development. If regulators decide that these drugs must be fully tested before drugs that are hard to blind could be approved, this could create considerable tension. In augmentation trials, regulators believe that the psychotherapeutic interventions must meet high standards; approval of one such strategy was declined because of concerns with the adequacy of the psychotherapeutic interventions.

Several other issues are unique to psychedelic clinical treatment and clinical trials. The number of participants with previous psychedelic experience is often high, raising questions about both blinding and motivation for participation in studies as well as the composition of the eventual candidates for clinical treatment with psychedelics. The partial legalization of psilocybin in Oregon, combined with the decriminalization and medicinal access to cannabis, may lead to tensions for developers: choose to wait for formal FDA approval, versus making safely manufactured psychedelics broadly available for purchase. At this time, there is considerable excitement and investment in these treatments. As in all treatments of psychiatric disorders, the development of predictors of treatment response could be a high priority. If we could develop such biomarker predictors of psychedelic agents, the pathway for approval could be accelerated because of bypassing the challenge of blinded trials. If the therapeutic potential of these treatments can be confirmed, it could be revolutionary. In the meantime, various treatments are making their way forward in development in the hopes that efficacy can be demonstrated even in the context of historical regulatory hurdles. Things are developing very rapidly, and much new information is to be expected in the next few months to years.

References

Andersen KAA, Carhart-Harris R, Nutt DJ, Erritzoe D. Therapeutic effects of classic serotonergic psychedelics: a systematic review of modern-era clinical studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;143:101–18.

Fonzo GA, Wolfgang AS, Barksdale BR, Krystal JH, Carpenter LL, Kraguljac NV, et al. Psilocybin: from psychiatric pariah to perceived panacea. Am J Psychiatry. 2025;182:54–78.

Vargas MV, Dunlap LE, Dong C, Carter SJ, Tombari RJ, Jami SA, et al. Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity through the activation of intracellular 5-HT2A receptors. Science. 2023;379:700–6.

Fonzo GA, Nemeroff CB. Psychedelics move toward mainstream medicine. Am Sci. 2025;113:170–7.

Sloshower J, Skosnik PD, Safi-Aghdam H, Pathania S, Syed S, Pittman B, et al. Psilocybin-assisted therapy for major depressive disorder: an exploratory placebo-controlled, fixed-order trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2023;37:698–706.

Goodwin GM, Malievskaia E, Fonzo GA, Nemeroff CB. Must psilocybin always “assist psychotherapy”?. Am J Psychiatry. 2024;181:20–5.

Goodwin GM, Aaronson ST, Alvarez O, Arden PC, Baker A, Bennett JC, et al. Single-dose psilocybin for a treatment-resistant episode of major depression. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1637–48.

Palhano-Fontes F, Barreto D, Onias H, Andrade KC, Novaes MM, Pessoa JA, et al. Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49:655–63.

Reckweg JT, van Leeuwen CJ, Henquet C, van Amelsvoort T, Theunissen EL, et al. A phase 1/2 trial to assess safety and efficacy of a vaporized 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine formulation (GH001) in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1133414.

Goodwin GM, Nowakowska A, Atli M, Dunlop BW, Feifel D, Hellerstein DJ, et al. Results from a long-term observational follow-up study of a single dose of psilocybin for a treatment-resistant episode of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2025;86:24m15449.

Iacoviello BM, Murrough JW, Hoch MM, Huryk KM, Collins KA, et al. A randomized, controlled pilot trial of the Emotional Faces Memory Task: a digital therapeutic for depression. NPJ Digit Med. 2018;1:21.

McIntyre RS, Kwan ATH, Mansur RB, Oliveira-Maia AJ, Teopiz KM, Maletic V, et al. Psychedelics for the treatment of psychiatric disorders: interpreting and translating available evidence and guidance for future research. Am J Psychiatry. 2025;182:21–32.

Mian MN, Dinh MT, Coker AR, Mitchell JM, Anderson BT. Psychedelic regulation beyond the controlled substances act: a three-dimensional framework for characterizing policy options. Am J Psychiatry. 2025;182:6–9.

Simonsson O, Goldberg SB, Chambers R, Osika W, Simonsson C, Hendricks PS. Psychedelic use and psychiatric risks. Psychopharmacology. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-023-06478-5.

Kettner H, Roseman L, Gazzaley A, Carhart-Harris RL, Pasquini L. Effects of psychedelics in older adults: a prospective cohort study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2024;32:1047–59.

Dittrich A, Lamparter D, Maurer M. 5D-ASC: Questionnaire for the assessment of altered states of consciousness. Zurich, Switzerland: PSIN PLUS; 2010.

Williamson D, Williamson L, Vaccarino V, Bremner JD. The pattern of dissociative symptoms differs between post-traumatic stress disorder and first esketamine administration for treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2025;389:119632.

Ballard ED, Zarate CA. The role of dissociation in ketamine’s antidepressant effects. Nat Commun. 2020;11:6431.

Hashimoto K. Are “mystical experiences” essential for antidepressant actions of ketamine and the classic psychedelics? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2025;275:1333–46.

Kim K, Che T, Panova O, DiBerto JF, Lyu J, Krumm BE, et al. Structure of a hallucinogen-activated G-coupled 5-HT2A serotonin receptor. Cell. 2020;182:1574–88.e19.

Johnston JN, Kadriu B, Allen J, Gilbert JR, Henter ID, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and serotonergic psychedelics: an update on the mechanisms and biosignatures underlying rapid-acting antidepressant treatment. Neuropharmacology. 2023;226:109422.

Ramaekers JG, Reckweg JT, Mason NL. Benefits and challenges of ultra-fast, short-acting psychedelics in the treatment of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2025;182:33–46.

Ly C, Greb AC, Cameron LP, Wong JM, Barragan EV, Wilson PC, et al. Psychedelics promote structural and functional neural plasticity. Cell Rep. 2018;23:3170–82.

Holze F, Becker AM, Kolaczynska KE, Duthaler U, Liechti ME. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral psilocybin administration in healthy participants. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2023;113:822–31.

Reckweg JT, Uthaug MV, Szabo A, Davis AK, Lancelotta R, Mason NL, et al. The clinical pharmacology and potential therapeutic applications of 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT). J Neurochem. 2022;162:128–46.

Bershad AK, Mayo LM, Van Hedger K, McGlone F, Walker SC, de Wit H. Effects of MDMA on attention to positive social cues and pleasantness of affective touch. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:1698–705.

Liechti ME, Saur MR, Gamma A, Hell D, Vollenweider FX. Psychological and physiological effects of MDMA (“Ecstasy”) after pretreatment with the 5-HT(2) antagonist ketanserin in healthy humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:396–404.

Holze F, Vizeli P, Müller F, Ley L, Duerig R, Varghese N, et al. Distinct acute effects of LSD, MDMA, and D-amphetamine in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:462–71.

Fountoulakis KN, Saitis A, Schatzberg AF. Esketamine treatment for depression in adults: a PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2025;182:259–75.

Calder CN, Kwan ATH, Teopiz KM, Wong S, Rosenblat JD, Mansur RB, et al. Number needed to treat (NNT) for ketamine and esketamine in adults with treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2024;356:753–62.

D’Souza DC. Cannabis, cannabinoids and psychosis: a balanced view. World Psychiatry. 2023;22:231–2.

Sheitman A, Bello I, Montague E, Scodes J, Dambreville R, Wall M, et al. Observed trajectories of cannabis use and concurrent longitudinal outcomes in youth and young adults receiving coordinated specialty care for early psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2024;267:313–21.

Kirlić N, Lennard-Jones M, Atli M, Malievskaia E, Modlin NL, Peck SK. Compass psychological support model for COMP360 psilocybin treatment of serious mental health conditions. Am J Psychiatry. 2025;182:126–32.

Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9.

Raison CL, Sanacora G, Woolley J, Heinzerling K, Dunlop BW, Brown RT. Single-dose psilocybin treatment for major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330:843–53.

Mind Medicine Phase 3 Press Release. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20250414503827/en/MindMed-Announces-First-Patient-Dosed-in-Phase-3-Emerge-Study-of-MM120-in-Major-Depressive-Disorder-MDD.

Wolfgang AS, Fonzo GA, Gray JC, Krystal JH, Grzenda A, Widge AS, et al. MDMA and MDMA-assisted therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2025;182:79–103.

Mitchell JM, Bogenschutz M, Lilienstein A, Harrison C, Kleiman S, Parker-Guilbert K, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nat Med. 2021;27:1025–33.

Weathers FW, Bovin MJ, Lee DJ, Sloan DM, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, et al. The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychol Assess. 2018;30:383–95.

Mitchell JM, Ot’alora G M, van der Kolk B, Shannon S, Bogenschutz M, Gelfand Y, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for moderate to severe PTSD: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2023;29:2473–80.

FDA Lykos FDA Advisory meeting. https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/updated-meeting-time-and-public-participation-information-june-4-2024-meeting-psychopharmacologic.

FDA Lykos Final meeting minutes. https://www.fda.gov/media/180463/download.

Cherian KN, Keynan JN, Anker L, Faerman A, Brown RE, Shamma A, et al. Magnesium-ibogaine therapy in veterans with traumatic brain injuries. Nat Med. 2024;30:373–81.

Wolfgang AS, McClair VL, Schnurr PP, Holtzheimer PE, Woolley JD, Stauffer CS, et al. Research and implementation of psychedelic-assisted therapy in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Psychiatry. 2025;182:17–20.

Mackey KM, Anderson JK, Williams BE, Ward RM, Parr NJ. Evidence brief: psychedelic medications for mental health and substance use disorders. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2022.

To improve care for veterans, VA to fund studies on new therapies for treating mental health conditions. Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs; 2024. https://news.va.gov/press-room/to-improve-care-for-veterans-va-to-fund-studies-on-new-therapies-for-treating-mental-health-conditions/.

Wolfgang AS, Hoge CW. Psychedelic-assisted therapy in military and veterans healthcare systems: clinical, legal, and implementation considerations. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2023;25:513–32.

Kim V, Wilson SM, Woesner ME. The use of classic psychedelics for depressive and anxiety-spectrum disorders: a comprehensive review. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2025;45:37–45.

Pagni BA, Zeifman RJ, Mennenga SE, Carrithers BM, Goldway N, Bhatt S, et al. Multidimensional personality changes following psilocybin-assisted therapy in patients with alcohol use disorder: results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2025;182:114–25.

Cai H, Jin Y, Liu R, Zhang Q, Su Z, Ungvari GS, et al. Global prevalence of depression in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological surveys. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;80:103417.

Gronemann FH, Jorgensen MB, Nordentoft M, Andersen PK, Osler M. Sociodemographicand clinical risk factors of treatment-resistant depression: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2020;261:221–9.

Zhdanava M, Pilon D, Ghelerter I, Chow W, Joshi K, Lefebvre P, et al. The prevalence and national burden of treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82:20m13699.

Bering JM, Gillespie CM. Avoiding stigma and sensationalism in therapeutic psilocybin communications: considerations for reaching older patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2025;33:1251–9.

Killikelly C, Smith KV, Zhou N, Prigerson HG, O'Connor MF, Kokou-Kpolou CK, et al. Prolonged grief disorder. Lancet. 2025;405:1621–32.

Ehrenkranz R, Agrawal M, Penberthy JK, Yaden DB. Narrative review of the potential for psychedelics to treat Prolonged Grief Disorder. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2024;36:879–90.

Beesley VL, Kennedy TJ, Maccallum F, Ross M, Harvey R, Rossell SL, et al. Psilocybin-Assisted supportive psychotherapy in the treatment of prolonged Grief (PARTING) trial: protocol for an open-label pilot trial for cancer-related bereavement. BMJ Open. 2025;15:e095992.

Salvetti G, Saccenti D, Moro AS, Lamanna J, Ferro M. Comparison between single-dose and two-dose psilocybin administration in the treatment of major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of current clinical trials. Brain Sci. 2024;14:829.

McIntyre RS, Alsuwaidan M, Baune BT, Berk M, Demyttenaere K, Goldberg JF, et al. Treatment-resistant depression: definition, prevalence, detection, management, and investigational interventions. World Psychiatry. 2023;22:394–412.

Seybert C, Schimmers N, Silva L, Breeksema JJ, Veraart J, Bessa BS, et al. Quality of reporting on psychological interventions in psychedelic treatments: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2025;12:54–66.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

Sabé M, Sulstarova A, Glangetas A, De Pieri M, Mallet L, Curtis L, et al. Reconsidering evidence for psychedelic-induced psychosis: an overview of reviews, a systematic review, and meta-analysis of human studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2025;30:1223–55.

McIntyre RS. Serotonin 5-HT2B receptor agonism and valvular heart disease: implications for the development of psilocybin and related agents. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2023;22:881–3.

Ghaznavi S, Ruskin JN, Haggerty SJ, King F, Rosenbaum JF. Primum non nocere: the onus to characterize the potential harms of psychedelic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2025;182:47–53.

Halpern JH, Lerner AG, Passie T. A review of hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) and an exploratory study of subjects claiming symptoms of HPPD. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:333–60.

Halpern JH, Pope HG Jr. Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder: What do we know after 50 years?. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69:109–19.

Roseman L, Nutt DJ, Carhart-Harris RL. Quality of acute psychedelic experience predicts therapeutic efficacy of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:974.

Goodwin GM, Aaronson ST, Alvarez O, Carhart-Harris R, Chai-Rees J, Croal M, et al. The role of the psychedelic experience in psilocybin treatment for treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2025;372:523–32.

Yaden DB, Griffiths RR. The subjective effects of psychedelics are necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021;4:568–72.

Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021;4:563–7.

Aaronson ST, van der Vaart A, Miller T, LaPratt J, Swartz K, Shoultz A, et al. Single-dose psilocybin for depression with severe treatment resistance: an open-label trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2025;182:104–13.

Dittrich A. The standardized psychometric assessment of altered states of consciousness (ASCs) in humans. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1998;31:80–4.

Aaronson ST, van der Vaart A, Miller T, LaPratt J, Swartz K, Shoultz A, et al. Single-dose synthetic psilocybin with psychotherapy for treatment-resistant bipolar type II major depressive episodes: a nonrandomized open-label trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81:555–62.

Earleywine M, Ueno LF, Mian MN, Altman BR. Cannabis-induced oceanic boundlessness. J Psychopharmacol. 2021;35:841–7.

Murray CH, Srinivasa-Desikan B. The altered state of consciousness induced by Δ9-THC. Conscious Cogn. 2022;102:103357.

Sanz C, Pallavicini C, Carrillo F, Zamberlan F, Sigman M, Mota N, et al. The entropic tongue: Disorganization of natural language under LSD. Conscious Cogn. 2021;87:103070.

Barksdale BR, Doss MK, Fonzo GA, Nemeroff CB. The mechanistic divide in psychedelic neuroscience: an unbridgeable gap?. Neurotherapeutics. 2024;21:e00322.

Chemerinski E, Forman J, Hopper A, Kamin S. Cooperative federalism and marijuana regulation. UCLA Law Rev. 2015;62:74–122.

Psilocybin Regulation: ORS 475A. 2021.

Code of Ordinances: 1 x28-300. Denver, CO; 2019.

Harvey PD. Psychedelics and older adults: What do they do compared to younger people?. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2024;32:1060–2.

Bogenschutz MP, Ross S, Bhatt S, Baron T, Forcehimes AA, Laska E. Percentage of heavy drinking days following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy vs placebo in the treatment of adult patients with alcohol use disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79:953–62.

Nayak SM, Bradley MK, Kleykamp BA, Strain EC, Dworkin RH, Johnson MW. Control conditions in randomized trials of psychedelics: an ACTTION systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2023;84:22r14518.

Wilkinson ST, Farmer C, Ballard ED, Mathew SJ, Grunebaum MF, Murrough JW, et al. Impact of midazolam vs. saline on effect size estimates in controlled trials of ketamine as a rapid-acting antidepressant. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:1233–8.

Kosik-Gonzalez C, Fu DJ, Chen LN, Lane R, Bloch MH, DelBello M, et al. Effect of esketamine on depressive symptoms in adolescents with major depressive disorder at imminent suicide risk: a randomized psychoactive-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2026;65:42–55.

Bloomfield-Clagett B, Ballard ED, Greenstein DK, Wilkinson ST, Grunebaum MF, Murrough JW, et al. A participant-level integrative data analysis of differential placebo response for suicidal ideation and nonsuicidal depressive symptoms in clinical trials of intravenous racemic ketamine. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;25:827–38.

Aday JS, Simonsson O, Schindler EAD, D’Souza DC. Addressing blinding in classic psychedelic studies with innovative active placebos. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2025;28:pyaf023.

Wen A, Singhal N, Jones BDM, Zeifman RJ, Mehta S, Shenasa MA, et al. Systematic review of study design and placebo controls in psychedelic research. Psychedelic Med. 2024;2:15–24.

Lehrner A, Hildebrandt TB, Yehuda R. Rethinking placebo-controlled clinical trials in psychedelic therapies for psychiatric illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2025;227:721–2.

Sziget B, Heifets B. Expectancy effects in psychedelic trials. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2024;9:512–21.

Horan WP, Kalali A, Brannan SK, Drevets W, Leoni M, Mahableshwarkar A, et al. Towards enhancing drug development methodology to treat cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia and other neuropsychiatric conditions: insights from 2 decades of clinical trials. Schizophr Bull. 2025;51:262–73.

Bugarski-Kirola D, Liu IY, Arango C, Marder SR. A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pimavanserin as an adjunctive treatment for the negative symptoms of schizophrenia (ADVANCE-2) in patients with predominant negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 2025:sbaf034. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaf034. Online ahead of print.

Bugarski-Kirola D, Blaettler T, Arango C, Fleischhacker WW, Garibaldi G, Wang A, et al. Bitopertin in negative symptoms of schizophrenia-results from the phase III FlashLyte and DayLyte studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;82:8–16.

Dwyer JB, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Johnson JA, Londono Tobon A, Flores JM, Nasir M, et al. Efficacy of intravenous ketamine in adolescent treatment-resistant depression: a randomized midazolam-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178:352–62.

Zhou Y, Lan X, Wang C, Zhang F, Liu H, Fu L, et al. Effect of repeated intravenous esketamine on adolescents with major depressive disorder and suicidal ideation: a randomized active-placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2024;63:507–18.

Peck SK, Shao S, Gruen T, Yang K, Babakanian A, Trim J, et al. Psilocybin therapy for females with anorexia nervosa: a phase 1, open-label feasibility study. Nat Med. 2023;29:1947–53.

Mueller L, Santos de Jesus J, Schmid Y, Müller F, Becker A, Klaiber A, et al. Safety and efficacy of repeated low-dose LSD for ADHD treatment in adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2025;82:555–62.

Danforth AL, Grob CS, Struble C, Feduccia AA, Walker N, Jerome L, et al. Reduction in social anxiety after MDMA-assisted psychotherapy with autistic adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235:3137–48.

Schneier FR, Feusner J, Wheaton MG, Gomez GJ, Cornejo G, Naraindas AM, et al. Pilot study of single-dose psilocybin for serotonin reuptake inhibitor-resistant body dysmorphic disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;161:364–70.

Newcorn JH, Nagy P, Childress AC, Frick G, Yan B, Pliszka S. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled acute comparator trials of lisdexamfetamine and extended-release methylphenidate in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. CNS Drugs. 2017;31:999–1014.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Harvey and Nemeroff: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work. Harvey and Nemeroff: drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. Harvey and Nemeroff: final approval of the version to be published. Harvey and Nemeroff: agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Philip D Harvey is supported by the National Institutes of Aging, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the US Department of Veterans Affairs. He has received consulting fees or travel reimbursements from Alkermes, BMS (Karuna Therapeutics), Boehringer Ingelheim, Kynexis, Minerva Neurosciences, and Neurocrine Biosciences. He has a research grant from Intracellular Therapeutics (Now part of Johnson and Johnson). He receives royalties from the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (Currently owned by Clario, Inc. and contained in the MCCB). He is the chief scientific officer of i-Function, Inc. and a Scientific Consultant to EMA Wellness, Inc. Charles B Nemeroff is supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Mental Health, the Texas Child Mental Health Consortium, and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Charles Nemeroff is a consultant for Engrail Therapeutics, Clexio Biosciences LTD, Galen Mental Health LLC, Goodcap Pharmaceuticals, ITI Inc, Sage Therapeutics, Senseye Inc, Precisement Health, Autobahn Therapeutics Inc, EMA Wellness, Denovo Biopharma LLC, Alvogen, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Reunion Neuroscience, Kivira Health, Inc, Wave Neuroscience, Patient Square Capital LP, Invisalert Solutions Inc., and Neurocrine Biosciences, LLC. Charles Nemeroff owns the following patents: Method and devices for transdermal delivery of lithium (US 6,375,990B1), Method of assessing antidepressant drug therapy via transport inhibition of monoamine neurotransmitters by ex vivo assay (US 7,148,027B2), Compounds, Compositions, Methods of Synthesis, and Methods of Treatment (CRF Receptor Binding Ligand) (US 8,551,996B2). Charles Nemeroff owns stock in Corcept Therapeutics Company, EMA Wellness, Precisement Health, Signant Health, Galen Mental Health LLC, Kivira Health, Inc., Denovo Biopharma LLC, and Senseye Inc.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Harvey, P.D., Nemeroff, C.B. Psychedelic therapeutics in psychiatric conditions. Neuropsychopharmacol. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-026-02335-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-026-02335-z