Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains the most challenging human malignancy that urgently needs effective therapy. Tissue factor (TF) is expressed in ~80% of PDAC and represents a potential therapeutic target. While a novel TF-ADC (MRG004A) demonstrated efficacy for PDAC and TNBC in a Phase I/II trial [Ref. 18], the functional role of TF in PDAC remains incompletely understood. We investigated the relationship between TF and the innate STING pathway. We found that patients with TF-overexpression had poor survival, very low levels of P-STING/P-TBK1, reduced amounts of ISGs and chemokines as well as low numbers of cytotoxic immunocytes in their tumor. In experimental models of mouse and human PDAC, tumor cell-intrinsic TF expression played a major role in silencing the cytosolic micronuclei sensing and cGAS-STING activation. This process involved a TREX1 exonuclease-dependent clearance of micronucleus-DNA accumulated in tumor cells. Treatment of tumors with TF-KO/shRNA or anti-TF antibody HuSC1-39 (parent antibody of MRG004A) triggered a rapid and proteasome-dependent degradation of TREX1 thereby restoring the STING/TBK1 cascade phosphorylation. TF-inhibition therapy promoted a robust STING/IRF3-dependent IFN/CCL5/CXCL9-11 production, immune effector cell infiltration and antitumor efficacy. Moreover, in the PBMC and cancer cell co-culture, TF-inhibition synergized with a STING agonist compound. A covalently conjugated TF antibody-STING agonist ADC strongly increased the efficacy of tumor-targeted STING agonism on chemokine secretion and tumor inhibition in vitro and in vivo. Thus, TF-inhibition reshapes an “immune hot” tumor environment. TF-targeted therapy warrants clinical investigation as a single agent or in combination with immunotherapy for treating TF-positive PDAC and TNBC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains the most challenging human malignancy worldwide. With a persistently increasing incidence and late diagnosis, the metastatic PDAC holds a 1-year 7% survival rate and will become the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality by the year 2030 [1,2,3]. Combination cytotoxic chemotherapy serves as first-line treatment and is responsible for only a modest improvement in survival [4,5,6]. While immunotherapies, notably immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), have improved survival in numerous cancer types, PDAC is mostly refractory to these interventions. In the search for resistance mechanisms, one recent focus in PDAC has been the fibrotic stroma, a physical barrier to chemotherapy and immune infiltration [7,8,9]. Little progress has been made regarding the impact of intrinsic alterations in tumor cells, particularly those driving resistance to immunotherapy in PDAC, on treatment outcomes. Therefore, further elucidation of the regulatory mechanism of immune evasion and development of new therapeutic strategies are urgently needed.

Tissue factor (TF) is a 47 kDa glycoprotein encoded by the clotting factor 3 (F3) gene. While TF is normally synthesized by the liver and functions in the extrinsic clotting pathway, its aberrant activation can greatly promote the malignant behavior of cancer [10]. Elevated TF expression is found on the surface of numerous malignant tumor types including that of PDAC [11,12,13,14]. TF plays multiple roles in tumor growth, metastasis and angiogenesis through coagulation proteases and cancer promoting macrophages [15, 16]. The TF/FVIIa complex can bind and stimulate protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2), which in turn stimulates the MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways. TF-PAR2-mediated intracellular signaling may operate in a parallel or bypass fashion to support tumor growth and disease progression [17]. TF is the molecular target of the FDA-approved ADC Tivdak for cervical cancer. Most recently, a novel TF-targeted ADC (MRG004A) demonstrated preliminary but promising antitumor efficacy for PDAC and TNBC [18] in a latest Phase I/II clinical trial (NCT04843709).

The Stimulator of interferon genes (STING) mediates inflammation upon cellular stress or infection and senses pathogenic nucleotides to activate the innate immune response [19, 20]. When cytosolic DNA is detected by cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate synthase (cGAS), the cGAS-STING pathway is activated [21, 22]. STING activation triggers a downstream cascade reaction via the STING-TBK1-IRF3 axis, stimulating the transcription of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) and mediating extensive biological functions of type I IFNs and other chemokines, which promotes the activation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) as well as the priming and infiltration of T cells to tumor sites [23, 24]. However, how the STING pathway coordinates with various oncogenic processes in tumor development and therapy resistance is poorly understood.

We have been interested in exploring new mechanism of TF in cancer cells, particularly whether TF regulates therapeutic resistance and promotes an immunosuppressive tumor environment. We previously created a potent and humanized TF antibody, HuSC1-39 (the parent antibody of MRG004A), and demonstrated its preclinical efficacy in treating PDAC and TNBC tumors [25]. We also discovered that activation of the TF-mTORC2 axis plays an important role in promoting resistance to KRAS-G12C inhibition in NSCLC [26]. We further showed that TF-overexpression in TNBC confers a poorly immunogenic “cold tumor” phenotype, in which the tumor cell-intrinsic TF blocks the synthesis and secretion of the T-cell recruiting chemokine CXCL9/10/11 [27]. These earlier results prompted us to investigate whether TF plays a role in the negative regulation of innate immunity.

In this study, we investigated the relationship between TF overexpression and STING pathway function in PDAC. We analyzed tumor mRNA expression data from TCGA and CCLE databases. We then performed PDAC tissue microarray (TMA) IHC/TSA staining, gene-knockout experiments and pharmacological intervention. We demonstrated that tumor cell-intrinsic TF expression plays a major role in blocking the activation of cGAS-STING pathway function. TF-targeted therapy normalized the cGAS-STING response, triggered an increased chemokine production, and immune effector cell infiltration and significantly improved antitumor efficacy.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and gene depletion

Cell lines of BxPC3, MDA-MB-231 (MDA-231), HCC1806, and HEK293T were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and HPAF-II cells were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). KPC-luc was provided by Professor Li Zhaoshen of the Shanghai Institute of Pancreatic Diseases. All the cells were cultured in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2 using standard cell culture methods and reagents (Invitrogen). The mouse KPC-luc cell-derived stable TF-KO clones were constructed employing CRISPR-Cas9 technology with TF sgDNA packaged in HEK293T cells [27]. The sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 2. The human TF depletion in HPAF-II, BxPC3, HCC1806 and MDA231 cells were performed with validated and doxycycline (Dox)-inducible pTRIPZ lentiviral TF-shRNA or NT-shRNA (Open Biosystem) as previously described [25]. Human STING was depleted via lentiviral shRNA (PGMLV, Genomeditech) via a similar method. The details of the shRNA sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Analysis of the TF transcriptome and tumor TMA

The mRNA expression data of pancreatic cancer patients (PDAC) were obtained from TCGA database (n = 176, https://www.cancer.gov). Two subgroups for PDAC patients expressing TF-High (TF-H, n = 88) and TF-Low (TF-L, n = 88) were subjected to analysis of survival curves and various biomarkers. All survival curves, heatmaps, columns and correlation plots were generated using GraphPad Prism 8.0. The immune cell fractions of all patient samples were examined via CIBERSORT (https://cibersort.stanford.edu/), an analysis tool developed by Newman et al. [28].

PDAC TMA (Cat# HPan-Ade170Sur-01) containing PDAC (n = 76) and PSCC (n = 4) was obtained from Shanghai Outdo Biotech Company and approved by the company Ethics Committee (reference number SHYJS-CP-1804012). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The TMA was stained with various markers as indicated. For the analysis, the immunofluorescence (IF) combined score (CS), quantified as fluorescence intensity multiplied by the percentage of positive cells. ImageJ was used to measure the average fluorescence intensity for each tumor sample. To determine the percentage of positive tumor cells, we selected three different fields (200×) and recorded the percentage of positive cells among all tumor cells in each field. For each stained biomarker, the CS values were converted proportionally to a scale of 0-4, with the highest CS score defined as a value of 4.

Immunoblotting, immunohistochemistry, TUNEL and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) are provided in “Supplementary Methods”

Picogreen staining

The cells were prepared in confocal dishes at a suitable density, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and processed according to the manufacture’s instructions for the Picogreen dsDNA reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cells were incubated with 5% BSA containing 0.3% Picogreen at 37 °C for 1 h, washed three times with PBS, and counterstained with DAPI before images were collected via confocal microscopy.

qRT-PCR, ELISA assay

Total RNA was extracted via TRIzol reagent and reverse transcribed into cDNA via the PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (TaKaRa; RR036A). TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ (TaKaRa; RR420A) was used in the Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time system. The mRNA level was normalized to that of GAPDH via the 2−ΔΔCT method. The primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Commercial ELISA kits for human CXCL10 (Liankebio, EK168), human IFN-γ (Liankebio, EK180), and mouse CXCL10 (Liankebio, EK268) were used to detect cytokine secretion from tumor cells and co-cultured medium from tumor cells and PBMC according to standard methods provided by the manufacturer. The concentration of cytokines was quantified according to the absorbance value and standard curve.

Co-culture of tumor cells and PBMC

Frozen human PBMC (Xidier Biotech, Jiangsu, China) were thawed and cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Luciferase labeled tumor cells were seeded in 96-well plates at an appropriate number of cells. The next day, PBMC was added to the tumor cells (E:T = 10:1). For the synergy experiment, 15 μg/ml HuSC1-39 and 1000 nM AN014 were added. For analysis of antitumor activity of the TF antibody-STING agonist ADC, serially diluted AN014, HuSC1-39, HuSC1-39-AN014 were added at a top dose of 1000 nM, and 1000 nM hIgG1 was added to the control group of tumor cells or PBMC. After appropriate incubation times, the culture supernatant was collected for subsequent cytokine detection and stored at −80 °C. For determination of the killing effect of PBMC on tumor cells, the luciferase activity of the tumor cells was measured.

Animal studies

In vivo efficacy studies were performed under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Fudan University (Reference number 2018-YL-YK-01). For mouse orthotopic tumor studies, 1 × 106 KPC-luc cells or human HPAF-II cells in Matrigel (BD, Cat#354248): PBS (ratio of 1:1, total volume of 50 μl) were injected into the tail of the pancreas in 6-week-old C57 mice or nude mice, respectively. Tumor growth was monitored weekly by a live imaging system (PerkinElmer, IVIS Spectrum). At the end of the experiment, all the mice were euthanized, and the tumors were harvested for analysis. For the subcutaneous tumor studies, 10 × 106 BxPC3, 2.5 × 106 HCC1806 or HPAF-II cells in 200 μl of sterile PBS were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of the nude mice. When the tumor size reached ~200 mm3, mice were randomized into treatment groups, and 10 mg/kg HuSC1-39 or hIgG1 was intravenously injected via the lateral tail vein.

Statistical analysis

All numerical data processing and statistical analysis were performed with Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism 8 software. Values of in vitro data are mean ± SD, and in vivo values are mean ± SE. P values were calculated by using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. In all tests, symbols are: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Results

Overexpression of TF in PDAC is associated with poor survival and a repressed innate immune STING pathway profile

We first performed TF IHC/TSA staining on PDAC TMA (n = 80). The TF expression level was measured as combined score (CS). TF-high (TF-H) patients (n = 55) accounted for 68.75% of the total number of cases and tended to have higher TNM stages (Fig. 1A). TF-H expression significantly affected patient prognosis, with TF-H vs. TF-L values of 8 months versus 31 months in all 80 patients. Analysis with stage-matched patients showed a similar worse prognosis for TF-H tumors (Fig. 1B). We stained TMAs with relevant markers. TF-H PDAC tumors presented elevated expression of P-ERK and P-AKT and reduced infiltration of CD8A+GZMB+ T cells, especially in patients diagnosed with stages III and IV (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. S1A). Unexpectedly, the TF-H tumors also showed drastically diminished levels of P-STING and its downstream mediator P-TBK1 (Fig. 1C, D). Results from 80 patients indicated a positive correlation of TF with P-ERK and P-AKT, and an inverse correlation of TF with P-STING, P-TBK1 and CD8A+GZMB+ T cells (Fig. 1E, F, Supplementary Fig. S1B). We next analyzed TF expression in 176 patients with pancreatic cancer in TCGA database. The TF mRNA level tended to be higher in patients with disease progression and recurrence (Supplementary Fig. S1C, D) and was related to poor survival (Supplementary Fig. S1E, F, G). CIBERSORT analysis revealed that the infiltration fraction of immune effector cells, such as CD8A+ T cells and activated NK cells in TF-H tumors was significantly lower than TF-L tumors, whereas the infiltration of immunosuppressive M2 macrophage was higher in TF-H tumors (Fig. 1G). As STING pathway stimulates ISGs [29, 30], we then compared their levels in top 25% and bottom 25% TF expression cohorts in TCGA. The TF-L tumors expressed significantly higher levels of ISGs (Fig. 1H) and chemokines CCL5, CXCL9-11 (Fig. 1I). Overall, these results show that TF-high expression promotes ERK and AKT signaling pathways and inhibits the cGAS-STING innate immune response, which collectively contributes to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.

A PDAC TMA were subjected to IHC/TSA staining. The proportions of TF-H/L tumors of various TNM stages were analyzed. B TF expression level and OS in all tumors or TNM stage-matched tumors were analyzed via the Kaplan–Meier method. C IHC staining of TF and related markers were analyzed in PDAC tumors as described in the Methods and shown as expression level heatmap. D Representative images of TF-H/L tumor staining are shown. E Analysis of TMA for TF correlation with the indicated biomarkers. F Analysis of TMA for levels of the indicated proteins in TF-H/L tumors. G Analysis of TCGA tumors for immune cell fractions in TF-H/L tumors via CIBERSORT. Analysis of TCGA tumors for correlation of TF expression and ISGs (H) and chemokines (I).

TF gene-knockout inhibits tumor growth and restores STING signaling in a syngeneic mouse model of PDAC

We employed CRISPR/Cas9 technology to knockout TF gene (TF-KO) in mouse KPC cells. The TF-KO efficiency was verified by immunoblotting and DNA sequencing in two independent clones (Fig. 2A). While TF-KO did not affect the proliferation of KPC cells in vitro, it substantially inhibited tumor growth when orthotopically implanted into mouse pancreas (Fig. 2B, C, Supplementary Fig. S2A). IHC/TSA studies with KPC tumor sections revealed a drastic reduction in Ki67+ and an increase in TUNEL+ apoptotic tumor cells (Fig. 2D). We then performed tumor staining for relevant biomarkers. Both the TF-KO-1 and TF-KO-2 tumors induced a DNA damage response (γ-H2AX) and active STING signaling (P-TBK1, P-STAT1) (Fig. 2E), leading to increased infiltration of antitumor cytotoxic T cells and dendritic cells (Fig. 2F). To determine whether this effect is directly due to the loss of TF in tumor cells, we performed immunoblotting on KPC-scramble, TF-KO-1 and TF-KO-2 cells in vitro. While KPC-TF-KO cells showed markedly decreased levels of P-AKT and P-ERK, the levels of P-TBK1, P-STAT1 and P-IRF3 were all substantially increased in these cells (Fig. 2G). qRT-PCR analysis of these same cells demonstrated an increase in CCL4, CCL5, and CXCL9-11 mRNA levels (Fig. 2H). Additionally, RNA-seq revealed a coordinated increase in the ISGs (IRF1, IRF7, ISG15, and IFI44) and chemokine genes (CCL5, CXCL10 and IFN-β) in both TF-KO-1 and TF-KO-2 cells (Fig. 2I). Collectively, these results highlight TF as a negative regulator of STING pathway activity in KPC cells. TF-KO reversed STING suppression and profoundly improved the antitumor immune environment.

A TF protein levels in KPC-Scramble and TF-KO cell lines were detected by immunoblotting. B In vitro proliferation rate of KPC-Scramble and TF-KO cell clones. C Representative bioluminescence image of mouse KPC-luc orthotopic pancreatic tumors and the tumor growth of Scramble, TF-KO-1 and TF-KO-2 (n = 3 each) are shown. D TUNEL staining and cell proliferation marker (Ki67) analysis. E Tumor sections were stained with various biomarkers and analyzed. F The infiltration levels of immune cells in Scramble and TF-KO tumor tissues were detected by IF. G Immunoblotting of scramble and TF-KO cells to analyze the various biomarkers. H The gene expression of CCL4, CCL5, CXCL9-11 was measured by qRT-PCR in Scramble and TF-KO cells. I RNA-seq results of Scramble and TF-KO tumor cells. An Expression heatmap of the STING activation signature genes is shown.

Restoration of STING signaling in orthotopically implanted human pancreatic tumor model treated with TF-targeted therapy

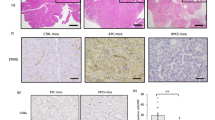

To explore the relationship between TF and STING pathway in human cancer models, we first performed immunoblotting on PDAC HPAF-II and BxPC3 cells, and TNBC MDA-231 and HCC1806 cells in vitro. Treatment with a Dox-inducible TF-shRNA or the anti-TF antibody HuSC1-39 in all four cell lines induced a robust active STING pathway signature, including P-TBK1, P-STAT1 and P-IRF3 (Fig. 3A, B). RNA-seq analysis of HPAF-II, BxPC3 and HCC1806 cells revealed further induction of the mRNA signature of ISGs and chemokines CCL5 and CXCL10 (Fig. 3C). We then implanted HPAF-II PDAC cells into the pancreas of nude mice. In vivo treatment with HuSC1-39 or Dox-inducible TF-shRNA greatly inhibited tumor growth (Fig. 3D, E; Supplementary Fig. S2B, C). TF-inhibition resulted in a decrease in P-ERK and P-AKT signaling (Fig. 3F) accompanied by the decrease in Ki67+ and increase in TUNEL+ tumor cells (Supplementary Fig. S2D). Antitumor efficacy was also observed in BxPC3 orthotopic and subcutaneous models (Supplementary Fig. S2E) and in TNBC HCC1806 subcutaneous model (Fig. S2F). TF inhibition in BxPC3 tumors also reduced Ki67+ cells and increased TUNEL+ cells (Supplementary Fig. S2G). Importantly, the HPAF-II tumors treated with TF-shRNA or HuSC1-39 presented an increased P-STING, P-TBK1, P-STAT1, and γ-H2AX levels, while the total STING level was not significantly altered (Fig. 3G, Supplementary Fig. S2H). Similarly activated STING pathway markers were observed in the treated BxPC3 tumors (Supplementary Fig. S2I). Moreover, TF-inhibition significantly promoted infiltration of NK cell, mature DCs and M1-like macrophage in tumors of HPAF-II (Fig. 3H) and BxPC3 (Supplementary Fig. S2J). These results indicate that similar to the KPC tumors, TF overexpression in human PDAC and TNBC tumors has a suppressive effect on the STING signaling pathway.

A, B Immunoblotting of P-TBK1, P-IRF3 and P-STAT1 in a panel of the indicated TF-H/L cells with TF-KO/TF-shRNA or HuSC1-39. C RNA-seq analysis of gene expression to detect STING activation status in TF-H cell lines after treatment with HuSC1-39. Representative bioluminescence images of pancreases-orthotopically implanted HPAF-II tumors containing either TF-shRNA (n = 4) (D) or treated with 10 mg/kg HuSC1-39 (n = 4) (E). Rx treatment. F Tumor sections (from D and E) were stained by IHC/TSA as indicated (n = 9). Representative images are shown. G TSA staining of the tumor sections as in F with P-STING and P-TBK1. H IHC/TSA staining of tumor sections as in F for biomarkers of NK, DC and M1-macrophage immune cells are shown and analyzed.

TF-inhibition triggers cytosolic micronuclei/cGAS accumulation, initiates STING phosphorylation and STING/IRF-dependent CCL5/CXCL10 production

To elucidate the cellular process underlying the STING repression in TF-high cells, we examined whether TF-inhibition induces cytosolic DNA micronuclei, a classical mechanism known to trigger the cGAS-STING innate immune responses [31]. Treatment with TF-KO/shRNA or HuSC1-39 induced accumulation of cytosolic micronuclei in TF-high cells, including KPC, HPAF-II, BxPC3, MDA-231 and HCC1806 cells (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Fig. S3A–D). Importantly, depletion of TF resulted in a robust increase in level of translocated and Ser-366-phosphorylated active STING, while the total STING level was not significantly altered (Fig. 4B). Immunoblotting study showed that in HPAF-II cells, STING-depletion completely prevented the TF inhibition-induced upregulation of P-TBK1, P-STAT1 and P-IRF3 (Fig. 4C), confirming that STING is essential for transmitting downstream signals. However, as demonstrated by the cGAS and dsDNA dual immunofluorescence, these STING-depleted cells remained largely responsive to TF inhibition-triggered micronuclei/cGAS accumulation (Fig. 4D). These findings suggest that TF acts to suppress the micronuclei/cGAS-sensing step prior to the involvement of STING. As TF-inhibition increased P-IRF3 expression (Fig. 3A, B), we performed qRT-PCR analysis of gene transcription. Treatment with TF-shRNA or HuSC1-39 increased mRNA levels of CCL5 and CXCL10 in HPAF-II and BxPC3 cells (Fig. 4E, F). However, CCL5 and CXCL10 transcription was prevented or compromised when STING was depleted (Fig. 4G, H). Collectively, these results support the notion that in TF-high PDAC and TNBC cells, TF-inhibition is sufficient to trigger innate immune activation by inducing cytosolic dsDNA/cGAS accumulation and STING phosphorylation, leading to an IRF3-dependent IFN/CCL5/CXCL10 response.

A Representative micrographs and quantification of micronuclei in KPC-Scramble and TF-KO cells. 100 cells per view were counted. B Immunofluorescence staining of P-STING and STING in HPAF-II cells treated with sh-NT or sh-TF. C Immunoblotting of STING pathway markers in HPAF-II cells treated with sh-STING or sh-STING and sh-TF. D Representative micrographs and quantification of the micronuclei and cGAS dual-positive HPAF-II cells treated with sh-TF or sh-TF and sh-STING. 100 cells per view were counted. qRT-PCR analysis of CCL5/CXCL10 mRNA in HPAF-II cells (E) and BxPC3 cells (F) treated with sh-TF or HuSC1-39. G mRNA level of STING, and CCL5/CXCL10 was analyzed by qRT-PCR after HPAF-II cells were treated with sh-STING or sh-STING and sh-TF. H HPAF-II cells without or with STING-depletion were treated with hIgG1 or HuSC1-39, and analyzed for CCL5/CXCL10 mRNA by qRT-PCR as described in the Methods section.

TF-targeted innate immune response involves downregulation of TREX1, an established innate checkpoint exonuclease

Because the immune response profile in TF-inhibited tumors is striking and TF is not known to regulate DNA integrity and metabolism, we considered that TF may act through other direct regulators. Analysis of TCGA and CCLE database found that the mRNA level of TREX1 tended to be elevated in TF-high PDAC and TNBC cohorts. Immunoblotting revealed that the TREX1 protein level was drastically decreased in the TF-depleted or HuSC1-39-treated KPC, HPAF-II and MDA-231 cells (Fig. 5C–E). We next performed HPAF-II cell immunofluorescence to view the dynamic localization of TF, STING and TREX1. In the HPAF-II shNT-treated control cells, a large fraction of STING appeared more uniformly dispersed in cytoplasm, while in TF-depleted cells, the bulk of activated STING was enriched in proximity of nucleus (Fig. 5F). TREX1 staining showed an abundant and dispersed appearance in control cells, and depletion of TF resulted in a dramatic loss of TREX1 expression (Fig. 5G). We next performed IHC/TSA staining on tumor sections. Consistent with the in vitro results, the HPAF-II and BxPC3 orthotopic tumors treated with TF-shRNA or HuSC1-39 displayed a nearly complete loss of TREX1 staining (Fig. 5H, I). Collectively, these results highlight a positive relationship between TF and TREX1. The accumulation of cytosolic micronuclei in TF-inhibited cells may be mediated through the loss of TREX1.

Analysis of TCGA and CCLE database for correlations of TF with TREX1 mRNA in tumor (A) or cell line (B). C–E Immunoblotting of TREX1 in the indicated cell lines and treatments. Localization and intensity of TF with STING (F) or TF with TREX1 (G) were analyzed by immunofluorescence staining of HPAF-II cells treated with sh-NT or sh-TF. H, I IHC/TSA staining of TF and TREX1 was performed on the orthotopic HPAF-II and BxPC3 tumor sections (obtained from Fig. 3D, E). Representative images are shown.

TF-inhibition triggers a rapid and proteasome pathway-dependent degradation of TREX1 protein thereby restoring cGAS-STING signaling function

To confirm the functional role of TREX1 in TF-dependent suppression of STING pathway, we overexpressed exogenous TREX1 in HPAF-II shNT and shTF cells, which significantly increased TREX1 level even when TF was depleted (Fig. 6A, C-left). The TREX1 expression in TF-depleted cells effectively prevented accumulation of cytosolic micronuclei (Fig. 6B, C-right) and re-suppressed P-TBK1/P-STING (Fig. 6A, D). We next examined how TF regulates TREX1 expression. Treatment with TF-KO/shRNA in the KPC, HPAF-II and MDA-231 cells did not reduce TREX1 mRNA transcription (Fig. 6E). Rather, the HuSC1-39-triggered loss of TREX1 and TF protein were both rescued by the proteasome inhibitor PS-341 but not the lysosomal inhibitor chloroquine (CQ) indicating the involvement of proteasome pathway (Fig. 6F). In KPC-derived TF-KO cells, PS-341 similarly rescued TREX1 protein implying the loss of TF function as the trigger for proteasome activation (Fig. 6G). We then performed cycloheximide (CHX) chase experiments to quantify TREX1 protein half-life in HPAF-II cell treated with hIgG1, HuSC1-39 or HuSC1-39 + PS-341. In all treatment conditions, the TREX1 protein stability followed closely with that of TF (Fig. 6H). These results overall demonstrate that inhibition of TF triggers a proteasome-dependent degradation of TREX1, which ultimately leads to cytosolic micronuclei accumulation and STING pathway activation.

A Immunofluorescence staining of the exogenous TREX1-transfected HPAF-II cells as indicated. B Cells as in A were quantified for micronuclei levels. Representative micrographs are shown. C TREX1 staining intensity was measured (left); Quantification of micronuclei at 100 cells per view were counted (right). D P-TBK1 and P-STING staining were quantified. E qRT-PCR analysis of TF, TREX1 mRNA in the indicated cells and conditions. Immunoblotting of HPAF-II (F) or KPC (G) cells after treatment with HuSC1-39, or HuSC1-39 + 10 nM PS-341 or 10 μM CQ for 24 h. H HPAF-II cells were treated with 20 µM CHX alone or in combination with HuSC1-39 or HuSC1-39 and PS-341 for various times and immunoblotted. Blot scans (left) and quantification (right) are shown.

TF-inhibition and STING agonist synergistically stimulate STING pathway in cancer cell-PBMC co-culture

We investigated whether TF inhibition could synergize with a STING agonist. We conducted several co-culture experiments employing TF antigen-positive cancer cells and PBMCs. The STING agonist AN014 has rather weak activity on its own [32]. We performed ELISAs and found that the secretion of CXCL10 and IFN-γ was increased by TF-shRNA, 15 μg/ml HuSC1-39 or 1000 nM AN014 in TF-positive cancer cells (MDA-231, HPAF-II, BxPC3). The chemokine level was further synergistically increased by TF-inhibition combined with AN014 (Fig. 7A, B). We then performed tumor cell viability assays (HPAF-II-luc, BxPC3-luc, MDA-231-luc), and found that the number of viable tumor cells was significantly decreased after combination treatment with TF inhibitor and AN014 compared with single treatment alone (Fig. 7C). Thus, collectively, these results revealed a potential therapeutic synergy between TF-inhibition and the STING agonist in promoting CXCL10/IFN-γ secretion and tumor cell killing.

A, B ELISA measurement of CXCL10 and IFN-γ in co-culture supernatants after treatment with TF-depletion, 15 μg/ml HuSC1-39, 1000 nM AN014 or the indicated combination for 24 h. C Luciferase-labeled cancer cells were co-cultured with PBMCs and treated as indicated for 48 h. Cancer cell viability was measured via a luciferase activity assay.

TF antibody-STING agonist ADC induces potent antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo

We then covalently conjugated STING agonist AN014 to TF antibody HuSC1-39, termed the HuSC1-39-AN014 ADC, with an average drug to antibody ratio (DAR) of 6.9 (Fig. 8A). HuSC1-39-AN014 exhibited a similar cell binding affinity compared with that of HuSC1-39 (Supplementary Fig. S4). To evaluate the antitumor effect in vivo, nude mice bearing HPAF-II tumors were treated with HuSC1-39, AN014 or HuSC1-39-AN014. It is clear that 5 mg/kg HuSC1-39-AN014 (equivalent of 0.16 mg/kg AN014) exhibited a profound tumor inhibition compared to that of 5 mg/kg HuSC1-39 or 2 mg/kg AN014 (Fig. 8B). Moreover, tumors treated with HuSC1-39-AN014 showed the most abundant levels of P-TBK1 (STING activation), NCR1+NK and CD86+ immune cells (Fig. 8C). These results demonstrate an in vivo antitumor synergy by TF inhibition and STING agonism. In co-culture experiments, serially diluted HuSC1-39-AN014 significantly increased the maximal secretion levels of CXCL10 and IFN-γ and decreased the EC50 values compared with those of single treatment with hIgG1, HuSC1-39, or AN014 (Fig. 8D). Compared with the free AN014, HuSC1-39-AN014 was 1700-fold and >2000-fold more potent in stimulating CXCL10 and IFN-γ, respectively (Fig. 8F). We also found that HuSC1-39-AN014 greatly enhanced tumor cell killing, as shown by the decreased proportions of viable MDA-231, HPAF-II, BxPC3 and HCC1806 cells (Fig. 8E). Compared with naked HuSC1-39 or free AN014, HuSC1-39-AN014 reduced the cell killing equivalent IC50 values by several to hundreds and thousands fold (Fig. 8G). These results are overall consistent with the data in Fig. 7, which support the synergy between TF-inhibition and STING agonist. Moreover, the ADC HuSC1-39-AN014 may serve as a novel therapeutic agent for treating TF-high expressing PDAC and TNBC.

A Structure of HuSC1-39-AN014. B In vivo efficacy of HuSC1-39-AN014 in HPAF-II xenograft tumors (n = 6). C IHC/TSA staining of tumor sections. D MDA-231 and PBMC co-cultures were treated with 1000 nM hIgG1 and serially diluted doses of AN014, HuSC1-39 and HuSC1-39-AN014 for 24 h. CXCL10 and IFN-γ in the culture supernatant were measured by ELISA. E The indicated cancer cell and PBMC co-cultures were treated with 1000 nM hIgG1, serially diluted doses of AN014, HuSC1-39 and HuSC1-39-AN014 for 48 h, and cell viability was measured by luciferase activity or the MTS assay. The results of ELISAs (F) and MTS (G) were analyzed statistically.

Discussion

TF is expressed in 80–90% of pancreatic cancer cases and is a compelling therapeutic target [33, 34]. Tumor immune environment plays important roles in PDAC progression and immunotherapy response [35,36,37]. Numerous studies have linked therapeutic effects of ICIs to the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway, as a lack of cytosolic DNA detection contributes to immune escape in cancer cells [38,39,40]. Type I IFNs significantly contribute to restraining tumor growth and extending host survival rates [41]. In this study, we revealed for the first time that TF facilitates inactivation of the cGAS-STING signaling pathway in PDAC and induces an immune-evasive “cold tumor” phenotype. Employing database analysis and PDAC TMA IHC/TSA staining, we showed that high TF expression is associated with disease progression and poor survival. These patient tumors contained very low levels of P-STING and P-TBK1, reduced ISGs and chemokine CCL4/CCL5/CXCL9-11 production, and ultimately, diminished infiltration of immune effector cells. Thus, TF overexpression could be a biomarker for intrinsic resistance to immunotherapy in PDAC.

We have shown that tumor cell intrinsic-TF played a major role in repressing cGAS-STING signaling. Treatment of a panel of TF-high PDAC and TNBC cell lines with TF-KO/shRNA or HuSC1-39 resulted in robust stimulation of STING pathway function in vitro and in vivo. In orthotopic KPC model in immunocompetent mice, TF-KO profoundly inhibited tumor growth and induced tumor apoptosis. This effect is mediated in a manner dependent on intra-tumoral cGAS-STING activation and secretion of chemokines CCL4/CCL5/CXCL9-11, which are known to improve both the innate and adaptive immunity responses [42]. In orthotopically implanted human PDAC HPAF-II and BxPC3 tumor models, TF-inhibition therapy also retarded tumor growth, increased apoptosis, decreased MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling, and activated cGAS-STING pathway. Based on these common observations, we conclude that TF-inhibition in these tumors reshapes an “immune hot” phenotype to elicit antitumor activity alone as a single agent or in combination with immunotherapy.

Malignant cancer cells tend to accumulate excessive micronucleus-derived cytosolic DNA due to genomic instability and uncontrolled cell proliferation. Cancer cells might also have developed ways to silence the sensing mechanism or disable the cGAS-STING functional mediators [43, 44]. In the current study, while TF-overexpression did not significantly affect the total protein level of STING or its downstream components, it prevented the translocation of STING to the Golgi apparatus where STING is phosphorylated and activated [45]. TF expression is positively related to TREX1, an established innate checkpoint exonuclease recently shown to degrade micronucleus-DNA and restrict the innate immune response in the context of cancer cells [46,47,48]. Moreover, we discovered that TF promotes the accumulation of TREX1 protein in TF-high PDAC cells, a regulatory event that explains how the micronucleus-DNA surveillance is disabled. Treatment of TF-high PDAC or TNBC cells with TF-inhibition therapy triggered a rapid and proteasome pathway-dependent degradation of TREX1, ultimately leading to the accumulation of cytosolic micronuclei and cGAS/STING recruitment and activation. This proposed mechanism is further strengthened by the TREX1-reconstitution experiment, where expression of exogeneous TREX1 in TF-depleted cells is sufficient to re-repress the micronucleus-DNA sensing and cGAS/STING activation. Thus, our results uncovered a novel mechanistic link between TF-overexpression and TREX1-mediated cytosolic DNA surveillance and may have implication in a range of TF-high cancers.

STING agonists have emerged as an interesting strategy for enhancing the antitumor immune response. However, its systemic use may be limited by dose-limiting toxicity or tumor resistance [49, 50]. Our data suggest that TF inhibition may present another path to achieve tumor-targeted STING agonism. In PBMC co-culture of PDAC or TNBC cells, TF-inhibition not only stimulated CXCL10/IFN-γ secretion and tumor cell killing, but also synergized with the STING agonist AN014. This observation was further strengthened by the use of the TF-STING agonist ADC, which greatly enhanced the tumor-targeted immune response and antitumor efficacy both in vitro and in vivo.

In summary, our study identified TF as an important immune resistance regulator in PDAC. TF-inhibition may provide a unique therapeutic opportunity to direct the host immune response against immunosuppressive cancers. As TF-ADC is being explored for its clinical efficacy in various cancer settings, TF-targeted therapy warrants further investigation as a single agent or in combination with immunotherapy for treating TF-positive PDAC and TNBC.

Data availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript files and are available upon request.

References

Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting Cancer Incidence and Deaths to 2030: The Unexpected Burden of Thyroid, Liver, and Pancreas Cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–21.

Nevala-Plagemann C, Hidalgo M, Garrido-Laguna I. From state-of-the-art treatments to novel therapies for advanced-stage pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17:108–23.

Tas F, Sen F, Keskin S, Kilic L, Yildiz I. Prognostic factors in metastatic pancreatic cancer: Older patients are associated with reduced overall survival. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1:788–92.

Wood LD, Canto MI, Jaffee EM, Simeone DM. Pancreatic cancer: pathogenesis, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:386–402.e381.

Bockorny B, Semenisty V, Macarulla T, Borazanci E, Wolpin BM, Stemmer SM, et al. BL-8040, a CXCR4 antagonist, in combination with pembrolizumab and chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer: the COMBAT trial. Nat Med. 2020;26:878–85.

Adamska A, Domenichini A, Falasca M. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: current and evolving therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1338.

Balachandran VP, Beatty GL, Dougan SK. Broadening the impact of immunotherapy to pancreatic cancer: challenges and opportunities. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:2056–72.

Elahi-Gedwillo KY, Carlson M, Zettervall J, Provenzano PP. Antifibrotic therapy disrupts stromal barriers and modulates the immune landscape in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2019;79:372–86.

Luo W, Wen T, Qu X. Tumor immune microenvironment-based therapies in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: time to update the concept. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024;43:8.

Unruh D, Horbinski C. Beyond thrombosis: the impact of tissue factor signaling in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:93.

Khorana AA, Ahrendt SA, Ryan CK, Francis CW, Hruban RH, Hu YC, et al. Tissue factor expression, angiogenesis, and thrombosis in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2870–5.

Xia Q, Zhang X, Chen Q, Chen X, Teng J, Wang C, et al. Down-regulation of tissue factor inhibits invasion and metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer. 2020;11:1195–202.

Hu Z, Shen R, Campbell A, McMichael E, Yu L, Ramaswamy B, et al. Targeting tissue factor for immunotherapy of triple-negative breast cancer using a second-generation ICON. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6:671–84.

Yu G, Li H, Wang X, Wu T, Zhu J, Huang S, et al. MicroRNA-19a targets tissue factor to inhibit colon cancer cells migration and invasion. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;380:239–47.

Gil-Bernabé AM, Ferjancic S, Tlalka M, Zhao L, Allen PD, Im JH, et al. Recruitment of monocytes/macrophages by tissue factor-mediated coagulation is essential for metastatic cell survival and premetastatic niche establishment in mice. Blood. 2012;119:3164–75.

Hisada Y, Mackman N. Tissue Factor and Cancer: Regulation, Tumor Growth, and Metastasis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2019;45:385–95.

Versteeg HH, Schaffner F, Kerver M, Ellies LG, Andrade-Gordon P, Mueller BM, et al. Protease-activated receptor (PAR) 2, but not PAR1, signaling promotes the development of mammary adenocarcinoma in polyoma middle T mice. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7219–27.

Park W, Zhang J, Dayyani F, Shan J, Liu R, Guo R et al. Phase I/II first-in-human study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tissue factor-ADC MRG004A in patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol.

Wang Y, Luo J, Alu A, Han X, Wei Y, Wei X. cGAS-STING pathway in cancer biotherapy. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:136.

Li A, Yi M, Qin S, Song Y, Chu Q, Wu K. Activating cGAS-STING pathway for the optimal effect of cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:1–12.

Ablasser A, Goldeck M, Cavlar T, Deimling T, Witte G, Röhl I, et al. cGAS produces a 2′-5′-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature. 2013;498:380–4.

Zhou W, Whiteley AT, De Oliveira Mann CC, Morehouse BR, Nowak RP, Fischer ES, et al. Structure of the human cGAS–DNA complex reveals enhanced control of immune surveillance. Cell. 2018;174:300–11.e311.

Borden EC. Interferons α and β in cancer: therapeutic opportunities from new insights. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:219–34.

Woo S, Fuertes MB, Corrales L, Spranger S, Furdyna MJ, Leung MY, et al. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing mediates innate immune recognition of immunogenic tumors. Immunity. 2014;41:830–42.

Zhang X, Li Q, Zhao H, Ma L, Meng T, Qian J, et al. Pathological expression of tissue factor confers promising antitumor response to a novel therapeutic antibody SC1 in triple negative breast cancer and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:59086–102.

Zhang Y, Liu L, Pei J, Ren Z, Deng Y, Yu K. Tissue factor overexpression promotes resistance to KRAS-G12C inhibition in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2024;43:668–81.

Ren Z, Xue Y, Liu L, Zhang X, Pei J, Zhang Y, et al. Tissue factor overexpression in triple-negative breast cancer promotes immune evasion by impeding T-cell infiltration and effector function. Cancer Lett. 2023;565:216221.

Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015;12:453–7.

Yum S, Li M, Frankel AE, Chen ZJ. Roles of the cGAS-STING Pathway in Cancer Immunosurveillance and Immunotherapy. Annu Rev Cancer Biol. 2019;3:323–44.

Schneider WM, Chevillotte MD, Rice CM. Interferon-stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:513–45.

Mackenzie KJ, Carroll P, Martin C-A, Murina O, Fluteau A, Simpson DJ, et al. cGAS surveillance of micronuclei links genome instability to innate immunity. Nature. 2017;548:461–5.

Chen Y, Chen K, L. I. P, Liu C, Wang J, Qiu Q et al. Highly active sting protein agonist compound. Patent Application US/2024/20240189320.

Nitori N, Ino Y, Nakanishi Y, Yamada T, Honda K, Yanagihara K, et al. Prognostic significance of tissue factor in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2531–9.

Saito Y, Hashimoto Y, Kuroda J, Yasunaga M, Koga Y, Takahashi A, et al. The inhibition of pancreatic cancer invasion-metastasis cascade in both cellular signal and blood coagulation cascade of tissue factor by its neutralisation antibody. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2230–9.

Bear A, Vonderheide RH. O’Hara MH. Challenges and opportunities for pancreatic cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:788–802.

Fan J, Wang M, Chen H, Shang D, Das JK, Song J. Current advances and outlooks in immunotherapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:32.

Ho WJ, Jaffee EM, Zheng L. The tumour microenvironment in pancreatic cancer—clinical challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17:527–40.

Lu C, Guan J, Lu S, Jin Q, Rousseau B, Lu T, et al. DNA sensing in mismatch repair-deficient tumor cells is essential for anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:96–108.e106.

Wang H, Hu S, Chen X, Shi H, Chen C, Sun L, et al. cGAS is essential for the antitumor effect of immune checkpoint blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114:1637–42.

Li W, Lu L, Lu J, Wang X, Yang C, Jin J, et al. cGAS-STING–mediated DNA sensing maintains CD8+ T cell stemness and promotes antitumor T cell therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12:eaay9013.

Liang Y, Hannan R, Fu Y. Type I IFN activating type I dendritic cells for antitumor immunity. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:3818–24.

Romero JM, Grünwald B, Jang G-H, Bavi PP, Jhaveri A, Masoomian M, et al. A four-chemokine signature is associated with a T-cell–inflamed phenotype in primary and metastatic pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:1997–2010.

Vanpouille-Box C, Demaria S, Formenti SC, Galluzzi L. Cytosolic DNA sensing in organismal tumor control. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:361–78.

Klara Rasmussen Bollerup L, Emil Leth L, Martin Roelsgaard J. The balance of STING signaling orchestrates immunity in cancer. Nat Immunol. 2024;25:1144–57.

Mărunţelu I, Constantinescu A-E, Covache-Busuioc R-A, Constantinescu I. The Golgi Apparatus: A Key Player in Innate Immunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:4120.

Tani T, Mathsyaraja H, Campisi M, Li Z, Haratani K, Fahey CG, et al. TREX1 inactivation unleashes cancer cell STING–interferon signaling and promotes antitumor immunity. Cancer Discov. 2024;14:752–65.

Lim J, Rodriguez R, Williams K, Silva J, Gutierrez AG, Tyler P, et al. The exonuclease TREX1 constitutes an innate immune checkpoint limiting cGAS/STING-mediated antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2024;12:663–72.

Mohr L, Toufektchan E, von Morgen P, Chu K, Kapoor A, Maciejowski J. ER-directed TREX1 limits cGAS activation at micronuclei. Mol Cell. 2021;81:724–738. e729.

Kuhl N, Linder A, Philipp N, Nixdorf D, Fischer H, Veth S, et al. STING agonism turns human T cells into interferon-producing cells but impedes their functionality. EMBO Rep. 2023;24:e55536.

Li S, Mirlekar B, Johnson BM, Brickey WJ, Wrobel JA, Yang N, et al. STING-induced regulatory B cells compromise NK function in cancer immunity. Nature. 2022;610:373–80.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Fudan University (EZF301002), NSF of China (81373442), NST Major Project of China (2018ZX09711002-008) and NBR 973 Program of China (2013CB932500). The authors thank Fudan School of Pharmacy Animal Facility and Instrument Center for their technical support. We thank Professor Zhaoshen Li of Shanghai Institute of Pancreatic Diseases for KPC-luc cells and for the technical support from Dr. Liang Liu and Dr. Jinpeng Pei.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: Y Xue, K Yu. Development of methodology: Y Xue, Y Wang. Acquisition of data: Y Xue, Y Wang, Z Ren. Analysis and interpretation of data: Y Xue, Y Wang, K Yu. Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: Y Xue, Y Wang, K Yu. Administrative, technical, or material support: Y Xue, K Yu. Study supervision: Y Xue, K Yu.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, Y., Wang, Y., Ren, Z. et al. Tissue factor promotes TREX1 protein stability to evade cGAS-STING innate immune response in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene 44, 739–752 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-024-03248-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-024-03248-1

This article is cited by

-

Deciphering cGAS-STING signaling: implications for tumor immunity and hepatocellular carcinoma

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2025)

-

AP-1-dependent c-Fos activation by TREX1 drives M2 macrophage polarization and mitigates osteoarthritis progression

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2025)