Abstract

Genome-wide molecular profiling has emerged as a promising approach for advancing the clinical management of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), with the potential to improve prognostic accuracy and enable more personalized treatment strategies. In this review, we summarize current evidence from genomic and epigenomic EAC stratification studies, highlighting the proposed molecular subtypes and evaluating their clinical relevance. We discuss how these subclassifications may inform disease outcomes, refine patient selection for specific therapies and uncover new treatment opportunities aligned with tumor molecular profiles. Additionally, we explore molecular subtypes associated with Barrett’s esophagus, a precursor lesion of EAC, and consider how these insights can help elucidate the mechanisms underlying EAC development. Such understanding may inform improved strategies for early tumor detection, risk stratification and prevention, ultimately aiming to reduce the burden of EAC. We also address the current challenges limiting the clinical application of these molecular classifiers, including restricted sample availability, insufficient validation and the difficulty of translating genome-wide findings into practical and clinical useful biomarkers. Integrating molecular subtyping into clinical workflows is a key step toward precision medicine in EAC, with the goal of enhancing treatment response rates and patient outcomes. Future advances will require collaborative efforts and robust clinical validation in large prospective studies to ensure that molecular stratification strategies can be effectively translated into improved management of EAC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the eleventh most diagnosed cancer and the seventh leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. It is classified into two main histological entities—squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma—with distinct epidemiologic, biologic and clinical characteristics [2]. Esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) is the most frequent type in Western countries, where its incidence has been rapidly rising.

A main risk factor for EAC is gastroesophageal reflux disease, with male sex and lifestyle factors such as obesity as contributing factors [3]. EAC usually develops from Barrett’s esophagus (BE), a metaplastic condition in which chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease replaces the normal stratified squamous epithelium with columnar-lined epithelium, typically containing intestinal-type goblet cells [4]. The progression from BE to EAC is a multistep process involving increasing grades of dysplasia [5] and accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations [6,7,8]. One of the pathways by which BE can advance to EAC involves complex genomic catastrophes, such as chromothripsis and breakage-fusion-bridge events, observed in around 20% of patients with dysplastic BE [9]. The occurrence of these mechanisms has been confirmed in several studies [10,11,12,13] and proposed to accelerate EAC development [14]. Although the annual risk of progression for individual BE patients is low, the overall lifetime risk is substantially elevated compared to the general population [5].

Despite improvements in EAC prognosis due to modern multimodal therapy regimens, the 5-year overall survival rates remain around 20% [15]. Several factors contribute to this dismal prognosis. First, in early phases, EAC is typically asymptomatic, and a large proportion of patients are diagnosed with metastatic or locally inoperable tumors. For these patients, curative therapy may not be available. Furthermore, the demanding surgery and the oncological treatment renders a significant subset of patients unfit for potential curative treatment. Lastly, a substantial percentage of patients undergoing curative treatment experiences tumor relapse with limited treatment options.

Across different therapeutic regimens, up to one fifth of patients with EAC receiving neoadjuvant oncologic treatment may achieve a pathologic complete response, i.e., absence of viable tumor tissue in the resected specimen [16]. Patients with residual disease in the resected specimen following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, along with selected patients with gastroesophageal metastatic or unresectable disease, may be offered treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [17]. Also in the context of immunotherapy, only a subset of patients show a complete or partial response [17].

The unclear drivers of therapeutic resistance and the variation of individual tumor response to same treatment in EAC underscore the need for improved molecular characterization. Although biomarkers such as PD-L1 expression, microsatellite instability (MSI) status and tumor mutation burden have been implemented in clinical practice, molecular profiling on the genome and epigenome level still has a limited role in EAC prognostication and treatment.

Genome-wide approaches have enabled tumor classification into clinically relevant subtypes. Well-established examples include the consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) in colorectal cancer [18] and the molecular subtypes identified in breast cancer [19]. Emerging molecular subgroups have also been identified in EAC and BE, offering important insights into their molecular diversity. This review summarizes genome-wide genomic and epigenomic stratification studies and evaluates EAC subclassifications for clinical utility. A summary of the key aspects discussed for EAC in this review is illustrated in Fig. 1. In addition, we explore reported molecular subtypes associated with BE and how they can contribute to elucidating the mechanisms driving EAC development.

In this review, studies on EAC were categorized according to the clinical questions they address, either the stratification’s value for prognostication or impact on therapy selection. Several studies combined therapeutic decisions with prognostic assessment of the patients. Particularly relevant examples of subtyping are highlighted. CIMP: CpG island methylator phenotype.

Selection criteria

Original research studies were eligible for inclusion in this review if they aimed to identify features that grouped EAC and/or BE cases into distinct subtypes or risk groups using genome-wide genomic or epigenomic approaches. Such criteria resulted in a list of 29 candidate studies. Among these, 5 used stratification strategies in which EAC molecular profiles were analyzed in a pan-cancer context. One of these pan-cancer studies was excluded due to the lack of information regarding cluster assignment of EAC cases.

Studies reporting combined results from EAC and squamous cell carcinoma (n = 4) were also excluded, as joint analysis of these two histological subtypes could introduce bias in patient stratification due to their distinct molecular profiles identified across multiple platforms [20]. The included studies were categorized according to the clinical questions they addressed, i.e., (i) prognostic relevance, (ii) influence on therapy selection and (iii) contribution to elucidating the mechanisms underlying EAC development.

Applying these selection criteria resulted in the inclusion of 24 studies (Fig. 2), summarized in Table 1. Among these, 22 studies investigated EAC either alone or in combination with BE, while the remaining 2 studies focused exclusively on BE.

Twenty-nine studies were eligible for inclusion. Among this, one was excluded due to lack of information regarding cluster assignment of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) cases in a pan-cancer stratification, and four others were excluded as they performed a joint evaluation of EAC and squamous cell carcinoma. Application of these selection criteria resulted in the inclusion of 24 studies, 22 of which investigated EAC either alone or in combination with Barrett’s esophagus (BE), while the remaining 2 studies focused exclusively on BE. Only around 40% of the studies stratifying EAC relied on unique data from “in-house” cohorts.

Molecular stratification and improvement of prognostic accuracy

Currently, the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system and histopathological characteristics such as tumor differentiation remain the cornerstones for predicting EAC prognosis [21]. While tumor response to neoadjuvant oncological therapy provides additional prognostic insight [22,23,24], these tools show limited ability to predict individual survival probabilities. For example, stage-matched patients present considerable variation in clinical outcomes and complete histopathological tumor response in resected specimens may not be an appropriate surrogate marker for survival [25]. This prognostic uncertainty underscores the need for more precise stratification tools. Molecular profiling addresses this gap by identifying biologically distinct tumor subtypes associated with disease outcome. Such stratification can help identify patients who have a lower chance of survival and may benefit from alternative therapeutic interventions, and spare patients with a higher chance of survival from therapies that may have limited benefit and potential adverse effects. Ultimately, this approach may allow for more accurate survival predictions beyond conventional clinical parameters.

Early molecular stratification studies used gene expression profiling to categorize patients with EAC. Already in 2010, Kim and colleagues grouped EAC into three clusters with distinct recurrence-free survival [26]. The cluster with the poorest prognosis showed strong enrichment of NF-κB pathway activity. Importantly, a two-gene signature comprising SPARC and SPP1 was validated as an independent prognostic marker for overall survival, with their combined expression significantly associated with patient outcomes even after adjusting for conventional clinicopathological factors. These results highlight the potential for subtype-specific molecular markers to refine risk assessment.

More recently, analysis of DNA methylation profiles from gastrointestinal (GI) adenocarcinomas grouped patients with EAC across four distinct pan-GI subtypes [27] (Fig. 3). These subtypes – hypermethylated, hypomethylated, intermediate and normal-like – showed a wide range of DNA methylation levels, revealing extensive epigenetic heterogeneity in EAC. Notably, 18% of EAC patients belonged to the normal-like subtype, which presented a low degree of aberrant DNA methylation and the poorest survival. Consistent with the range of DNA methylation levels, the four pan-GI subtypes including EAC cases overlapped with a range of CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) statuses.

CIMP-like subtypes

CIMP is characterized by widespread hypermethylation at CpG islands in gene promoter regions, resulting in transcriptional silencing of multiple genes. CIMP was originally described in colorectal cancer by Toyota et al. in 1999 [28], and has since been identified in various other cancer types, including glioma, bladder -, pancreatic -, lung -, hepatocellular -, and gastric cancer [29]. While the prognostic significance of CIMP varies among cancer types [29], it is often associated with more aggressive biology in GI tumors, particularly in colorectal cancer [30,31,32].

In EAC, genome-wide DNA methylation studies have identified CIMP-like subtypes [33,34,35,36], although their clinical significance remains unclear. In 2011, Kaz and colleagues were among the earliest to analyze variations in CpG island methylation in EAC and BE [33]. By using microarrays to analyze global DNA methylation patterns, they identified high- and low-methylation epigenotypes, along with CpG sites potentially involved in disease progression. This groundwork described for the first time methylation subgroups in BE and EAC, and established aberrant DNA methylation as a key feature of EAC pathogenesis.

Building on this, Krause and colleagues [34] also used DNA methylation arrays to identify two EAC subtypes: a CIMP-like hypermethylated group and a non-CIMP group. The CIMP-like group was characterized by extensive CpG island hypermethylation, including high methylation levels of CIMP markers previously proposed in gastric and colorectal cancer [37,38,39]. This supports the utility of an array-based approach for detecting CIMP in EAC. The hypermethylated tumors also showed significant overlap with regions marked by the repressive histone modification H3K27me3 and binding sites for Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 proteins, indicating coordinated epigenetic gene silencing. Clinically, patients with the most hypermethylated tumors had significantly poorer survival outcomes compared to other groups. Analysis of an independent cohort from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) in the same study further supported the presence of a CIMP-like phenotype in EAC. However, the prognostic value of this stratification has not been assessed. It is also noteworthy that probe selection was based on CpG islands with highest methylation variation observed across tumors and with low methylation in normal squamous epithelium. While this approach is appropriate for detecting CIMP, it may have missed other potentially clinically relevant methylation patterns, such as CpG sites characterized by frequent hypomethylation.

Further advancing the understanding of DNA methylation in EAC, Sánchez-Vega et al. [36]. classified 87 EAC tumors from TCGA into three categories – CIMP-positive, CIMP-intermediate and CIMP-negative – based on differentially methylated CpG islands (probes) when comparing tumor and healthy adjacent tissue. According to TCGA original study (ref), these data were generated from samples with high tumor purity ( ≥ 60%; Table 1). Approximately one-third of EAC samples were classified as CIMP-positive, exhibiting pronounced DNA hypermethylation, while CIMP-negative tumors had methylation profiles closer to those observed in normal tissues. Interestingly, unlike colorectal cancer, no significant association between MLH1 promoter hypermethylation and CIMP categories was found in EAC, suggesting possible mechanistic differences in epigenetic regulation between these cancers. The authors highlighted that subdividing samples according to CIMP status could reduce heterogeneity within cancer subtypes and result in more uniform molecular and phenotypic characteristics. This could help achieve more consistent response rates in clinical trials.

In a broader context, Liu et al. [35] integrated 79 TCGA EAC samples into a pan-GI molecular taxonomy, revealing that GI adenocarcinomas displayed markedly higher frequencies of CpG island hypermethylation compared to non-GI adenocarcinomas, partly attributable to the higher CIMP frequency. Patients with EAC were distributed across four out of the seven pan-GI subtypes identified – CIMP-high, gastroesophageal CIMP-low and two non-CIMP subtypes. When present, the CIMP-like methylation patterns were associated predominantly with chromosomal instability rather than MSI or MLH1 methylation, which are more characteristic of lower GI tumors. This work underscored once again the molecular heterogeneity of EAC and its closer resemblance to chromosomally unstable gastric cancers than to colorectal cancers.

Collectively, these studies provide compelling evidence that CIMP-like methylation patterns exist in EAC and may contribute to tumor heterogeneity and progression. However, their clinical significance remains uncertain due to inconsistent validation across cohorts, and lack of standardized criteria for CIMP classification currently limit its clinical application. Future research should focus on establishing consensus definitions for CIMP in EAC and validating its prognostic and predictive utility in large, well-characterized patient cohorts.

Classification models for improved mortality risk assessment

Ideally, prognostic evaluation in EAC would associate patient outcomes to specific molecular biomarkers involved in tumor progression. Molecular classifiers may facilitate individualized mortality risk assessment, enabling clinicians to more accurately identify patients with a low survival probability for tailored therapeutic interventions. Furthermore, the discovery of prognostically relevant genes may reveal novel biological pathways and potential therapeutic targets, advancing precision medicine and ultimately improving patient survival.

Several molecular signatures developed from genome-wide approaches have been suggested for prognostic assessment of patients with EAC, stratifying them into high- and low-risk groups. While studies differ in the type of data used to build the prognostic models, the methodologies for identifying these signatures are similar: prognostic-related features are derived from differentially altered genes or regions between tumor and normal samples, followed by selection using various modalities of Cox regression analyses. Patients are then categorized into risk groups based on the median survival risk score calculated from the identified signatures, with those in the low-risk group demonstrating improved outcomes compared to those in the high-risk groups.

In 2021, Lan et al. [40] identified a 5-mRNA signature (SLC26A9, SINHCAF, MICB, KRT19 and MT1X) that outperformed the traditional TNM staging system in predicting 3-year survival rates for EAC. This signature maintained predictive accuracy across all tumor stages and was validated in an external dataset, supporting its utility as a robust prognostic biomarker. In the study of Mao et al. [41], a four-gene expression signature (ALAD, ABLIM3, IL17RB and IFI6) strongly associated with overall survival was identified. This signature showed particularly strong predictive performance in advanced-stage disease. Expanding beyond gene expression, Chen et al. incorporated DNA methylation data into their analyses and defined a signature comprising four methylation driven genes (GPBAR1, OLFM4, FOXI2, and CASP10) [42], while Li et al. [43] used DNA methylation data alone to developed a 3-CpG prognostic classifier (mapped to ITGA1 and MCC genes). Time-dependent ROC curve analysis indicated that the methylation-based classifier outperformed established clinical risk factors – including age, gender, BMI, smoking, alcohol use and tumor stage, – in predicting patient survival. This classifier effectively distinguished low- and high-risk groups across both early and advanced stages. Multivariate analyses showed that the risk scores calculated from all these signatures were independent predictors of overall survival for EAC. While the study of Lan et al. achieved external validation, those of Mao et al., Chen et al. and Li et al. lack such validation, limiting their immediate clinical applicability despite initially promising results.

Molecular stratification and personalized treatment selection

The highly heterogeneous molecular landscape of EAC complicates the development of effective targeted therapies. Currently, patients are typically treated with a “one-size-fits-all” approach, including surgery and perioperative chemotherapy and/or radiation. Clinical guidelines suggest the use of trastuzumab for HER2-positive EAC patients with metastatic disease [44], based on its demonstrated survival benefit when combined with chemotherapy in HER2-positive metastatic gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancers [45]. Zolbetuximab has also been recently recommended as first-line therapy in combination with chemotherapy for treatment of claudin 18.2 (CLDN18.2)-positive, HER2-negative, locally advanced, and metastatic gastric and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinomas [46, 47]. This suggests that CLDN18.2-targeted therapies could be applied to EAC outside the gastroesophageal junction, but clinical validation is still needed. In addition, anti-PD-1 inhibitors are used for EAC treatment but, in the adjuvant setting, this is done regardless of PD-1 or PD-L1 expression levels, likely resulting in suboptimal efficacy.

Molecular classification systems could therefore give insights into new strategies for therapeutic intervention. Advances in molecular profiling – including genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics and tumor microenvironment (TME) analysis – have revealed distinct EAC subtypes with specific biological characteristics and with the potential to guide more precise therapies and, in some cases, complement prognostic assessment.

Subtypes with potential actionable targets

Whole-genome sequencing of 129 EAC cases by Secrier et al [48]. identified three subtypes with suggested therapeutic relevance: (i) DNA damage repair induced, BRCA-like tumors, with homologous recombination defects, likely sensitive to PARP inhibitors; (ii) hypermutated tumors with high neoantigen loads, potential candidates for immunotherapy; and (iii) C > A/T dominant, aging-associated tumors likely benefiting from conventional chemotherapies. Importantly, these treatment suggestions have been derived from in vitro experiments using cell lines representative of each subtype and from findings in other cancer types, hence requiring validation specifically in EAC. Moreover, frequent co-amplification of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) was observed across subtypes, suggesting that combinatorial RTK inhibition might be necessary to overcome resistance mechanisms. Translating subtype classification into clinical benefit requires methodologies that are both practical and accessible. While whole-genome sequencing remains costly, the same subtypes were identified using cost-effective low-coverage sequencing, making this approach more feasible for routine clinical use and expanding opportunities for tailored treatment.

Transcriptomic profiling of 215 EAC samples from three independent cohorts performed by Guo et al. [49] added another dimension, distinguishing gastric-like (Subtype I) and squamous-like (Subtype II) EACs. Subtype I displayed an epithelial and keratinocyte differentiation signature, with molecular features resembling gastric adenocarcinoma. In contrast, subtype II was characterized by cytochrome P450-related metabolism signatures and shared gene expression patterns with esophageal squamous carcinoma. The authors hypothesized that patients in subtype II could be more sensitive to chemotherapy than patients in subgroup I. However, with only three annotated samples analyzed this hypothesis remains speculative. Moreover, distinct mutation signatures were observed in both subgroups, though there was no significant difference in overall mutation burden. Considering the findings from Secrier et al. [48], it can be hypothesized that both transcriptomic subtypes are represented within the hypermutated subgroup. Consequently, ICIs, suggested for hypermutated tumors, could potentially benefit both subtype I and II, depending on neoantigen load. This underscores the molecular complexity of EAC and highlights the importance of multi-omics stratification.

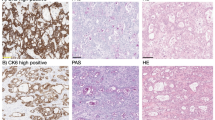

Epigenetic profiling by Yu et al. [50] using an in-house discovery dataset (n = 23) further explored EAC stratification with therapeutic relevance. The group identified four methylator subtypes: high, intermediate, low, and minimal. These subtypes resembled previously described CIMP groups [34, 36] and were validated in the TCGA EAC cohort (n = 87). By analyzing the genomic alterations in both cohorts and integrating methylome and transcriptome data from all TCGA samples in the validation cohort, the authors further characterized the subtypes. They found that most actionable features were present in the high methylator subtype, specifically characterized by ERBB2 alterations (mutations or amplifications) and silencing of the tumor suppressor PTPN13 by aberrant methylation. This subtype also displayed an elevated mutational load, suggesting a possible overlap with Secrier’s hypermutated group and theoretically implying shared vulnerabilities to combined epigenetic and immunotherapy strategies. Since only samples with high tumor content were included in the study (Table 1), the presented differences in the number of actionable features are plausible and not likely an effect of variable tumor cell percentages across the four methylation subtypes. Moreover, drug sensitive assays in EAC cell lines representing the methylator subtypes suggested distinct susceptibilities to conventional and targeted therapies, which, if validated clinically, may improve precision medicine for EAC patients. Thus, DNA methylation-based subtyping could provide insights into the functional roles of epigenetic alterations in EAC and serve as predictive markers. However, Yu et al. [50] promising results are based on relatively small cohorts (discovery n = 23; validation n = 87), necessitating further validation.

Jammula et al. further provided a comprehensive description of epigenetic heterogeneity, stratifying a larger cohort of patients with BE (n = 150) and EAC (n = 285) collected by the Oesophageal Cancer Clinical and Molecular Stratification (OCCAMS) Consortium [51]. They identified four subtypes associated with patient outcome and potential therapy response. Subtype 1 showed DNA hypermethylation, aligning with a CIMP-like profile, as most hypermethylated probes overlapped with CpG islands and promoter regions. The characteristics of this subtype also matched the high methylator subtype proposed by Yu et al. [50], including high mutation burden and ERBB2 amplifications. Jammula and colleagues proposed that patients in subtype 1 could be sensitive to DNA methyltransferase and topoisomerase I inhibitors, which have shown efficacy in tumors with high levels of methylation [50, 52]. Interestingly, this subtype had the best overall survival. Subtype 3 did not show significant changes in DNA methylation compared to normal tissues and it was associated with the poorest survival, in line with other studies indicating that the DNA methylation “normal like” subtype in GI adenocarcinomas, including EAC, is linked to worse prognosis [27]. Notably, gene expression data revealed significant infiltration of both innate and adaptive immune cells in this subtype, a feature typically associated with better immunotherapy response. However, frequent MDM2 amplification – often linked to resistance to ICIs [53] – was also observed in this subtype, creating a clinical contradiction where apparent immunological responsiveness conflicts with molecular resistance mechanisms. The study did not include data on immunotherapy administration or outcomes in this subgroup, leaving it unclear whether MDM2 amplification ultimately contradict the potential benefits suggested by immune cell infiltration. Additionally, analysis of EAC organoids provided insights into potential subtype-specific targeted therapeutics. For example, CDK2 inhibitors were more effective in organoids representing hypomethylated subtype 4, characterized by CCNE1 amplification, an alteration reported to be sensitive to CDK2 inhibitors.

Sundar and colleagues identified a DNA methylation signature that stratified patients with EAC into two clusters with distinct survival outcomes based on treatment received [54]. Both clusters included patients who had undergone neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery or surgery alone. In cluster 1, patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy showed significantly improved median overall survival compared to those treated with surgery alone. Conversely, patients in cluster 2 had no survival benefit from chemotherapy, suggesting that alternative strategies are needed for this group. These observations demonstrate the predictive value of the epigenetic signature, as the survival differences were specifically tied to chemotherapy response rather than general prognosis. The signature was subsequently validated in an independent cohort, strengthening its potential for predicting survival outcome and chemotherapy response in EAC.

Notably, by integrating genetic, epigenetic and expression data from TCGA, Hoadley and colleagues identified 28 pan-cancer clusters [55], seven of which included EAC cases. Cell-of-origin patterns strongly influenced tumor clustering and EAC was highly linked to pan-GI lineages. Yet, EAC cases were also distributed across more heterogeneous clusters characterized by immune-related features or distinct copy-number alteration patterns (Fig. 3). In addition, a minority of cases exhibited molecular similarities to HER2-amplified breast cancers or squamous cell carcinomas. This framework suggests broad opportunities for targeted therapeutic strategies in EAC. The conserved pathways across GI cancers, along with the resemblance to HER2-amplified tumors, support the potential utility of therapies such as trastuzumab, which has demonstrated clinical benefit in gastric and colorectal cancers with similar molecular features [56, 57]. Furthermore, the significant proportion of EAC cases in the Mixed (Stromal/Immune) cluster (24%), displaying strong immune-related signaling profiles, suggests that a subset of patients with EAC may have increased susceptibility to immunotherapeutic approaches.

Immunological profiling with potential clinical relevance

As research indicates that patient response to immunotherapy is strongly influenced by dynamic tumor-immune interactions [58], comprehensive analysis of the TME may offer new opportunities to identify patient subgroups most likely to benefit from immunotherapy. In other tumor types, classifying patients into immunological “hot” or “cold” subtypes has proven successful in guiding clinicians on the feasibility of immunotherapy [59]. In EAC, however, robust biomarkers predictive of immunotherapy response have been lacking, which may contribute to the generally limited efficacy of these treatments in most patients. Although PD-L1 expression, tumor mutational burden, and MSI have been investigated [17], none have consistently or reliably predicted response to immunotherapy. Stratifying EAC cases based on their immunological states therefore appears to be a promising approach for developing more individualized and effective therapeutic strategies [60].

By integrating RNA expression data and immune infiltrate scores Ling et al. developed a classifier to stratify patients with EAC into two subtypes with significant prognostic differences and distinct immunological profiles [61]. Age- and tumor stage-stratified survival analyses confirmed the prognostic value of these subtypes. The subtype with the best prognosis showed up-regulated immune-related signaling pathways and enriched immune cell infiltration, including CD8 + /CD4 + T cells, B cells, as well as M2 macrophages and cancer-associated fibroblasts. This subtype also presented high enrichment scores for antigen-presenting signatures, suggesting that it could be highly sensitive to immunotherapy. Conversely, the subtype with the poorest prognosis showed significantly decreased macrophage function, indicating that patients in this group may respond better to chemotherapy or combination therapy.

In another study by Naeini et al. [62], the proportion of 18 immune cell types in the TME of pre-treatment samples was used to categorize 68 patients with EAC into four immune clusters associated with overall and progression-free survival. Among these, immune hot, immune cold and immune suppressed clusters were identified. The immune hot cluster was enriched with lymphocytes (i.e., CD4+ and CD8 + T cells), myeloid-derived cells (i.e., macrophages, monocytes and dendritic cells) and demonstrated high levels of immune checkpoint molecules, suggesting a potential response to immune checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. This cluster had the best outcome, consistent with one of Ling’s clusters [61], and with previous studies linking immune hot tumors to prolonged survival in other cancer types [63]. On the other hand, the immune cold cluster was characterized by low immune infiltrate and low expression of immune checkpoint molecules, suggesting limited benefit from ICI therapy. However, enrichment of metabolic pathways in tumors within this cluster suggested that alternative therapy strategies could be effective. The immune suppressed cluster, enriched with macrophages and myeloid-derived cells but depleted of lymphocytes, was associated with the worst survival. Tumors in this cluster showed high expression of immune suppression markers, such as SPP1, and invasive phenotypes marked by increased angiogenesis, G2M checkpoint activity, and activation of MYC and E2F targets – features mostly reduced in the immune hot cluster. Although not statistically significant, lower pathological responses to cisplatin/5-FU chemotherapy were found in this cluster compared to the others.

The characterization of immunological profiles in EAC has also been explored in broader contexts. Using a collection of immune expression signatures scores, Thorsson et al. classified TCGA tumors – including 76 EAC – into six major immune subtypes spanning multiple cancer tissue types [64]. Each immune subtype was defined by dominant immunogenomic features with potential therapeutic implications and likely impact on prognosis, as the subtypes were associated with both overall survival and progression-free interval. Patients with EAC were distributed across five clusters – C1: wound healing, C2: IFN-γ dominant, C3: inflammatory, C4: lymphocyte depleted and C6: TGF-β dominant (Fig. 3) – demonstrating the immune heterogeneity of EAC. Only the immunologically quiet C5 cluster, characterized by low immune cell infiltration, did not include any EAC patients. The poorest outcomes were observed for C4 and C6, whereas C3 showed the most favorable prognosis. These observations are consistent with above-mentioned studies [61, 62], where immunosuppressed TMEs were associated with poor prognosis, while tumors with high immune cell infiltration had better outcomes. The comprehensive immunogenomic characterization of these clusters allowed the suggestion of subtype-appropriate therapies, spanning from potential response to ICIs in tumors with high lymphocyte infiltration and neoantigen load (as in C2), to the use of TGF-β inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy (for patients in C6).

Immune-based classification models for improved mortality risk assessment

Molecular signatures developed for prognostic assessment of patients with EAC may also inform potential response to immunotherapy or suggest new immunotherapy targets, especially if they are associated with immune-related genes. Patient stratification based on such signatures could enable improved treatment interventions for those with otherwise poor prognoses. The following studies aimed to build prognostic models for EAC based on the differential expression of immune-related genes between EAC and normal tissue samples. Prognosis-associated, differentially expressed features were refined into signatures that allowed categorization of patients into high- and low-risk groups, based on the median survival risk score calculated from the identified signatures. Patients in the low-risk groups consistently showed improved outcomes compared to those in the high-risk groups, and the two groups frequently display distinct immune landscapes.

From gene expression data, Yang and colleagues [65] constructed a four-gene immune-related signature associated with prognosis. The survival risk score calculated from this signature was an independent risk factor for overall survival in EAC patients. Differences in immune cell infiltration, tumor immune escape (TIDE) scores and expression of immune checkpoint-related genes suggested that patients in the high-risk group might be more suitable for immunotherapy. Another immune-based prognostic signature based on gene expression data was proposed by Zhang et al. [66], and the survival rate difference between high- and low-risk groups remained significant when patients were stratified by age or tumor stage. Furthermore, multivariate analyses and a nomogram indicated that combining the survival risk score with sex, M stage and tumor stage could accurately predict survival in patients with EAC. The proportions of M0, M1, and plasma cells differed between the high- and low-risk groups, although the potential for targeted therapy response has not been explored.

Molecular stratification and elucidation of the mechanisms underlying EAC carcinogenesis

Understanding the molecular changes occurring during transition from BE to EAC may provide essential mechanistic insights into early EAC carcinogenesis, and may help improve early detection, risk stratification and prevention strategies [67]. A significant number of publications have characterized the genomic events occurring in BE, as reviewed by Killcoyne and Fitzgerald [68]. While such studies are important for understanding the mechanisms underlying EAC development, they do not use these events for direct patient stratification and were therefore not included in this review.

Genome-wide molecular profiles of BE samples have been compared to those of EAC [34, 49, 51]. Characterizing inter-lesional molecular heterogeneity may allow identification of novel tumor suppressors involved in esophageal carcinogenesis and potential biomarkers for malignant progression of BE. Krause et al. investigated genome-wide methylation profiles of EAC, BE and normal squamous esophagus [34]. The most variable probes across all samples separated EAC and BE from normal squamous esophagus, but not EAC from BE, highlighting the molecular similarity between tumors and their precursor lesion. As a result, EAC and BE were grouped together in two distinct clusters, one of them characterized by a CIMP-like methylation pattern. The distribution of BE samples across clusters was independent of whether they were collected from patients with EAC. Jammula et al. reported similar findings, showing that methylation profiles of BE more closely overlap with EAC than with normal tissues [51]. These observations confirm that aberrant methylation is an early event in EAC progression [8, 69], and that BE and EAC samples share genome-wide methylation features [7, 34, 51], distinct from normal squamous esophagus. Interestingly, one of the four subtypes identified by Jammula et al. was dominated by BE cases (83% against 17% EAC). The few EAC cases in this subtype had adjacent BE, moderate differentiation, and the best prognosis compared to EAC cases in the other subtypes. These observations are in agreement with another study showing that EAC with adjacent BE has a better prognosis [70].

Molecular similarities between BE and EAC are also supported by transcriptomics and genomics data. In a meta-analysis of gene expression data from three independent EAC cohorts, Guo et al. identified two subtypes with specific expression and mutation profiles [49]. The gastric-like subtype II exhibited gene expression patterns closely resembling those found in BE, supporting the concept of a progression pathway from BE to EAC. Additionally, whole-genome sequencing has shown that BE exhibits a high mutational burden [11, 71], present already in non-dysplastic BE samples, underscoring the presence of extensive early molecular changes in this premalignant condition. Complex genomic catastrophes found in dysplastic BE [9] have been suggested as a potential driver of malignant transformation [14, 68]. Structural rearrangement patterns derived from such complex genomic events were used by Nones and colleagues [14] to subtype 22 EAC cases. The number of structural variants and their genomic distribution revealed considerable inter-tumor heterogeneity and enabled categorizing EAC cases into unstable genomes, scattered and complex localized.

These studies, in agreement with others, indicate that molecular alterations occur early in EAC development and that they can be valuable for tumor stratification. However, some studies have highlighted molecular differences that distinguish BE from EAC [33, 51]. In addition to similarities in hypermethylation patterns, Jammula et al. also identified a set of unmethylated probes highly specific to the BE-dominated subtype, suggesting that these may maintain tissue specificity in BE and become methylated in EAC [51]. This subtype lacked DNA methylation at binding sites for key transcription factor motifs (including HNF4A/G, FOXA1/2/3, GATA6 and CDX2), consistent with their role in EAC progression. Similarly, Kaz et al. found distinct methylation signatures between EAC, BE, normal squamous esophagus and high-grade dysplasia [33]. By identifying molecular signatures that may separate EAC from BE, the authors provided insights into EAC progression. This approach also offers the potential for developing biomarkers for early detection and risk stratification among patients with BE.

To identify specific markers for these histological groups, Kaz et al. conducted differential methylation analysis, revealing the highest number of differentially methylated CpG sites between EAC and squamous epithelium (SQ; 442 sites), followed by BE vs. SQ (225 sites), and only a few between EAC and BE (17 sites) [33]. The low number of sites differentiating EAC and BE supports the substantial overlap in methylation profiles, but the identified sites may be involved in progression and may serve as diagnostic or prognostic markers.

Although BE is recognized as a pre-malignant condition, clinical heterogeneity exists among individuals with BE. Clustering analyses of BE samples independently from EAC have revealed methylation subtypes in BE [33, 50]. Yu et al. [50] identified four distinct non-dysplastic BE methylation subtypes that mirrored those identified in EAC, without significant differences in gene alteration frequency between them. As for EAC, Kaz et al. [33] found two BE clusters with distinct methylation profiles, described as high and low methylation epigenotypes, analogous to CIMP groups in other cancer types. The presence of similar clusters in BE and EAC suggests that molecular heterogeneity is established at the BE stage and highlights the importance of molecular profiling for identifying patients at higher risk of progression.

Common challenges limiting the clinical application of EAC molecular stratification studies

Despite research efforts in molecular subtyping of EAC, several limitations currently restrict the clinical utility of published stratification studies and prognostic signatures. First, EAC is a relatively rare cancer type, and most studies have therefore relied on modest sized cohorts (Table 1). Limited sample availability is also reflected by the fact that approximately 60% of the studies included here used data from the same patient cohorts, publicly available from TCGA or Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), rather than producing novel datasets from independent, population-representative patient cohorts (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Moreover, validation of findings in separate, external cohorts is often lacking (Table 1).

Furthermore, the subgroup stratification and the relative frequency of various molecular alterations risk being influenced by underlying confounding factors such as bias in clinical representativeness or variable tumor cell fraction within samples. Although several studies have included samples with a high tumor content only (Table 1), few of them have systematically addressed the distribution of tumor percentages across and within the subtypes [36] to evaluate its potential impact on subtype assignment.

Most studies reviewed here used surgical specimen samples from locally advanced, resectable tumors, while a large proportion of patients with EAC are diagnosed with metastatic or locally inoperable tumors. Although understanding molecular characteristics of localized disease can provide valuable information applicable to the metastatic context, – for example by informing therapeutic strategies or identifying biomarkers relevant throughout disease progression, – relying solely on data from locally advanced tumors may limit the applicability of findings in advanced disease.

Finally, methodological differences, such as the choice of genome-wide platform, feature selection strategies, clustering methods and study design, may also influence the molecular subtyping are identified and whether these can be validated.

Clinical implications and future directions

Despite challenges, molecular profiling may advance clinical management of EAC by providing more precise prognostic assessments and tailored therapeutic interventions. Stratification efforts have identified genomic and epigenomic subgroups with the potential to inform disease outcomes, refine patient selection for existing therapies, and uncover new treatment opportunities.

To enable clinical translation, future research should focus on larger, well-characterized, prospective patient cohorts and rigorous external validation. Collaboration across centers serve as an effective approach to overcome current sample limitations and to ensure consistent methodologies and standardization throughout studies. Such initiatives may also facilitate the use of patient cohorts that are representative with respect to demographic characteristics and clinically relevant features, including tumor stage.

Transparent reporting of tumor cell fraction within samples, clinical variables and stratification methods is also necessary to enhance reproducibility and facilitate fair comparison between studies. Controlling for these factors is important to ensure the quality of data analyses and assess the clinical relevance of proposed subtypes.

Moreover, stratification of BE, either independently or combined with EAC, may provide valuable insights into the early mechanisms driving tumor development. Such findings may facilitate the identification of biomarkers for malignant progression in BE, which could improve early detection, refine risk stratification, and inform effective prevention strategies to reduce the burden of EAC. Prioritizing the development and validation of molecular markers for patient subgroups at higher risk of malignant progression, as well as for early detection of EAC, remains essential for improving survival outcomes.

Collectively, these strategies may facilitate the implementation of promising molecular classifiers in routine clinical practice, enable the design of clinical trials with more homogeneous populations, and ultimately advance precision medicine in EAC.

References

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229–63.

Jajosky A, Fels Elliott DR. Esophageal cancer genetics and clinical translation. Thoracic Surg Clin. 2022;32:425–35.

Jiang W, Zhang B, Xu J, Xue L, Wang L. Current status and perspectives of esophageal cancer: a comprehensive review. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2025;45:281–331.

Minacapelli CD, Bajpai M, Geng X, Cheng CL, Chouthai AA, Souza R, et al. Barrett’s metaplasia develops from cellular reprograming of esophageal squamous epithelium due to gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2017;312:G615–22.

Beydoun AS, Stabenau KA, Altman KW, Johnston N. Cancer risk in Barrett’s esophagus: a clinical review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:6018.

Stachler MD, Camarda ND, Deitrick C, Kim A, Agoston AT, Odze RD, et al. Detection of mutations in Barrett’s esophagus before progression to high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:156–67.

Xu E, Gu J, Hawk ET, Wang KK, Lai M, Huang M, et al. Genome-wide methylation analysis shows similar patterns in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:2750–6.

Pinto R, Hauge T, Jeanmougin M, Pharo HD, Kresse SH, Honne H, et al. Targeted genetic and epigenetic profiling of esophageal adenocarcinomas and non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus. Clin Epigenet. 2022;14:77.

Newell F, Patel K, Gartside M, Krause L, Brosda S, Aoude LG, et al. Complex structural rearrangements are present in high-grade dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus samples. BMC Med Genom. 2019;12:31.

Katz-Summercorn AC, Jammula S, Frangou A, Peneva I, O’Donovan M, Tripathi M, et al. Multi-omic cross-sectional cohort study of pre-malignant Barrett’s esophagus reveals early structural variation and retrotransposon activity. Nat Commun. 2022;13:1407.

Paulson TG, Galipeau PC, Oman KM, Sanchez CA, Kuhner MK, Smith LP, et al. Somatic whole genome dynamics of precancer in Barrett’s esophagus reveals features associated with disease progression. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2300.

Luebeck J, Ng AWT, Galipeau PC, Li X, Sanchez CA, Katz-Summercorn AC, et al. Extrachromosomal DNA in the cancerous transformation of Barrett’s oesophagus. Nature. 2023;616:798–805.

Bao C, Tourdot RW, Brunette GJ, Stewart C, Sun L, Baba H, et al. Genomic signatures of past and present chromosomal instability in Barrett’s esophagus and early esophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat Commun. 2023;14:6203.

Nones K, Waddell N, Wayte N, Patch A-M, Bailey P, Newell F, et al. Genomic catastrophes frequently arise in esophageal adenocarcinoma and drive tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5224.

Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA A Cancer J Clinic. 2025;75:10–45.

Gaber CE, Sarker J, Abdelaziz AI, Okpara E, Lee TA, Klempner SJ, et al. Pathologic complete response in patients with esophageal cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2024;13:e7076.

Dedecker H, Teuwen L-A, Vandamme T, Domen A, Prenen H. The role of immunotherapy in esophageal and gastric cancer. Clinical Colorectal Cancer. 2023;22:175–82.

Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, de Reyniès A, Schlicker A, Soneson C, et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2015;21:1350–6.

Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, Van De Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–52.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Analysis Working Group: Asan University, BC Cancer Agency, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Broad Institute, Brown University, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature. 2017;541:169–75.

Berry MF. Esophageal cancer: staging system and guidelines for staging and treatment. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6 Suppl 3:S289–297.

Gunadasa I, Papa N, Khu YL, Brown W, Burton P, Haydon A, et al. Differential impact of post-neoadjuvant stage on overall survival for surgically treated oesophageal cancer following neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Esophagus. 2024;7:2–2.

Davies AR, Gossage JA, Zylstra J, Mattsson F, Lagergren J, Maisey N, et al. Tumor stage after neoadjuvant chemotherapy determines survival after surgery for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2983–90.

Schwameis K, Zehetner J, Hagen JA, Oh DS, Worrell SG, Rona K, et al. Esophageal adenocarcinoma stage III: survival based on pathological response to neoadjuvant treatment. Surgical Oncol. 2017;26:522–6.

Okui J, Nagashima K, Matsuda S, Sato Y, Kawakubo H, Ruhstaller T, et al. Evaluation of pathological complete response as a surrogate endpoint for overall survival in resectable oesophageal cancer: integrated analysis of individual patient data from phase III trials. Br J Surg. 2025;112:znaf131.

Kim SM, Park Y-Y, Park ES, Cho JY, Izzo JG, Zhang D, et al. Prognostic biomarkers for esophageal adenocarcinoma identified by analysis of tumor transcriptome. Tan P, editor. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15074.

Pinto R, Vedeld HM, Lind GE, Jeanmougin M. Unraveling epigenetic heterogeneity across gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas through a standardized analytical framework. Mol Oncol. 2024;19:1117–31.

Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Issa JP. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8681–6.

Hughes, Melotte LAE, de Schrijver V, de Maat J, Smit M, VTHBM, et al. The CpG island methylator phenotype: what’s in a name?. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5858–68.

Jia M, Gao X, Zhang Y, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H. Different definitions of CpG island methylator phenotype and outcomes of colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Clin Epigenet. 2016;8:25.

Vedeld HM, Merok M, Jeanmougin M, Danielsen SA, Honne H, Presthus GK, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype identifies high risk patients among microsatellite stable BRAF mutated colorectal cancers. Intl J Cancer. 2017;141:967–76.

Wang J, Deng Z, Lang X, Jiang J, Xie K, Lu S, et al. Meta-analysis of the prognostic and predictive role of the CpG Island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Dis Markers. 2022;2022:4254862.

Kaz AM, Wong C-J, Luo Y, Virgin JB, Washington MK, Willis JE, et al. DNA methylation profiling in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma reveals unique methylation signatures and molecular subclasses. Epigenetics. 2011;6:1403–12.

Krause L, Nones K, Loffler KA, Nancarrow D, Oey H, Tang YH, et al. Identification of the CIMP-like subtype and aberrant methylation of members of the chromosomal segregation and spindle assembly pathways in esophageal adenocarcinoma. CARCIN. 2016;37:356–65.

Liu Y, Sethi NS, Hinoue T, Schneider BG, Cherniack AD, Sanchez-Vega F, et al. Comparative molecular analysis of gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:721–35.e8.

Sánchez-Vega F, Gotea V, Chen Y-C, Elnitski L. CpG island methylator phenotype in adenocarcinomas from the digestive tract: methods, conclusions, and controversies. WJGO. 2017;9:105.

Hinoue T, Weisenberger DJ, Lange CPE, Shen H, Byun H-M, Van Den Berg D, et al. Genome-scale analysis of aberrant DNA methylation in colorectal cancer. Genome Res. 2012;22:271–82.

Weisenberger DJ, Siegmund KD, Campan M, Young J, Long TI, Faasse MA, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2006;38:787–93.

Zouridis H, Deng N, Ivanova T, Zhu Y, Wong B, Huang D, et al. Methylation subtypes and large-scale epigenetic alterations in gastric cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:156ra140.

Lan T, Liu W, Lu Y, Luo H. A five-gene signature for predicting overall survival of esophagus adenocarcinoma. Medicine. 2021;100:e25305.

Mao Y, Zhang H, He X, Chen J, Xi L, Chen Y, et al. A four-gene signature predicts overall survival of patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma. Transl Cancer Res. 2024;13:1382–93.

Chen Y, Wang J, Zhou H, Huang Z, Qian L, Shi W. Identification of prognostic risk model based on DNA methylation-driven genes in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Tian S, editor. BioMed Res Int. 2021;2021:6628391.

Li D, Zhang L, Liu Y, Sun H, Onwuka JU, Zhao Z, et al. Specific DNA methylation markers in the diagnosis and prognosis of esophageal cancer. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11:11640–58.

Muro K, Lordick F, Tsushima T, Pentheroudakis G, Baba E, Lu Z, et al. Pan-Asian adapted ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic oesophageal cancer: a JSMO-ESMO initiative endorsed by CSCO, KSMO, MOS, SSO and TOS. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:34–43.

Bang Y-J, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687–97.

Shah MA, Shitara K, Ajani JA, Bang Y-J, Enzinger P, Ilson D, et al. Zolbetuximab plus CAPOX in CLDN18.2-positive gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: the randomized, phase 3 GLOW trial. Nat Med. 2023;29:2133–41.

Shitara K, Lordick F, Bang Y-J, Enzinger P, Ilson D, Shah MA, et al. Zolbetuximab plus mFOLFOX6 in patients with CLDN18.2-positive, HER2-negative, untreated, locally advanced unresectable or metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (SPOTLIGHT): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;401:1655–68.

The Oesophageal Cancer Clinical and Molecular Stratification (OCCAMS) Consortium, Secrier M, Li X, De Silva N, Eldridge MD, Contino G, et al. Mutational signatures in esophageal adenocarcinoma define etiologically distinct subgroups with therapeutic relevance. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1131–41.

Guo X, Tang Y, Zhu W. Distinct esophageal adenocarcinoma molecular subtype has subtype-specific gene expression and mutation patterns. BMC Genom. 2018;19:769.

Yu M, Maden SK, Stachler M, Kaz AM, Ayers J, Guo Y, et al. Subtypes of Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma based on genome-wide methylation analysis. Gut. 2019;68:389–99.

Jammula S, Katz-Summercorn AC, Li X, Linossi C, Smyth E, Killcoyne S, et al. Identification of subtypes of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma based on DNA methylation profiles and integration of transcriptome and genome data. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1682–97.e1.

Zhang Z, Wang G, Li Y, Lei D, Xiang J, Ouyang L, et al. Recent progress in DNA methyltransferase inhibitors as anticancer agents. Front Pharm. 2022;13:1072651.

Fang W, Zhou H, Shen J, Li J, Zhang Y, Hong S, et al. MDM2/4 amplification predicts poor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors: a pan-cancer analysis. ESMO Open. 2020;5:e000614.

Sundar R, Ng A, Zouridis H, Padmanabhan N, Sheng T, Zhang S, et al. DNA epigenetic signature predictive of benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy in oesophageal adenocarcinoma: results from the MRC OE02 trial. European J Cancer. 2019;123:48–57.

Hoadley KA, Yau C, Hinoue T, Wolf DM, Lazar AJ, Drill E, et al. Cell-of-origin patterns dominate the molecular classification of 10,000 tumors from 33 types of cancer. Cell. 2018;173:291–304.e6.

Gunturu KS, Woo Y, Beaubier N, Remotti HE, Saif MW. Gastric cancer and trastuzumab: first biologic therapy in gastric cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2013;5:143–51.

Zheng-Lin B, Bekaii-Saab TS. Treatment options for HER2-expressing colorectal cancer: updates and recent approvals. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2024;16:17588359231225037.

Creemers JHA, Lesterhuis WJ, Mehra N, Gerritsen WR, Figdor CG, de Vries IJM, et al. A tipping point in cancer-immune dynamics leads to divergent immunotherapy responses and hampers biomarker discovery. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9:e002032.

Galon J, Bruni D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:197–218.

Lonie JM, Brosda S, Bonazzi VF, Aoude LG, Patel K, Brown I, et al. The oesophageal adenocarcinoma tumour immune microenvironment dictates outcomes with different modalities of neoadjuvant therapy - results from the AGITG DOCTOR trial and the cancer evolution biobank. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1220129.

Ling C, Zhou X, Gao Y, Sui X. Identification of immune subtypes of esophageal adenocarcinoma to predict prognosis and immunotherapy response. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15:605.

M. Naeini M, Newell F, Aoude LG, Bonazzi VF, Patel K, Lampe G, et al. Multi-omic features of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in patients treated with preoperative neoadjuvant therapy. Nat Commun. 2023;14:3155.

Sang M, Ge J, Ge J, Tang G, Wang Q, Wu J, et al. Immune regulatory genes impact the hot/cold tumor microenvironment, affecting cancer treatment and patient outcomes. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1382842.

Thorsson V, Gibbs DL, Brown SD, Wolf D, Bortone DS, Ou Yang T-H, et al. The immune landscape of cancer. Immunity. 2018;48:812–30.e14.

Yang C, Cao F, He Y. An immune-related gene signature for predicting survival and immunotherapy efficacy in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Med Sci Monit. 2023;29:e940157.

Zhang X, Yang L, Kong M, Ma J, Wei Y. Development of a prognostic signature of patients with esophagus adenocarcinoma by using immune-related genes. BMC Bioinforma. 2021;22:536.

Barchi A, Dell’Anna G, Massimino L, Mandarino FV, Vespa E, Viale E, et al. Unraveling the pathogenesis of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: the “omics” era. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1458138.

Killcoyne S, Fitzgerald RC. Evolution and progression of Barrett’s oesophagus to oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21:731–41.

Eads CA, Lord RV, Wickramasinghe K, Long TI, Kurumboor SK, Bernstein L, et al. Epigenetic patterns in the progression of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3410–8.

Sawas T, Killcoyne S, Iyer PG, Wang KK, Smyrk TC, Kisiel JB, et al. Identification of prognostic phenotypes of esophageal adenocarcinoma in 2 independent cohorts. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1720–1728.e4.

Ross-Innes CS, Becq J, Warren A, Cheetham RK, Northen H, O’Donovan M, et al. Whole-genome sequencing provides new insights into the clonal architecture of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1038–46.

Funding

This work was supported by the Norwegian Cancer Society (project numbers 216129, 223073, and 220115; the Norwegian Esophageal Cancer Consortium – NORECa) and the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (project number 2024032).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RP and GEL conceived and planned the paper; RP carried out the literature search, article collection and organization; RP, IVS, HMV and HP drafted the manuscript; RP and IVS designed the figures; GEL supervised the writing process, revised the first draft and made critical contributions; TM critically revised the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pinto, R., Sjurgard, I.V., Pharo, H. et al. Molecular stratification of esophageal adenocarcinoma: implications for prognosis and treatment strategy. Oncogene 45, 353–367 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-025-03650-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-025-03650-3