Abstract

The USP37 gene encodes a deubiquitylase (DUB), which catalyzes the proteolytic removal of ubiquitin moieties from proteins to modulate their stability, cellular localization or activity. Its expression is downregulated in a subgroup of medulloblastomas driven by constitutive activation of sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling. Patients with SHH-driven medulloblastomas with elevated expression of the RE1 silencing transcription factor (REST) and reduced expression of USP37 have poor outcomes. In previous studies, we showed sustained proliferation of SHH-medulloblastoma cells due to blockade of terminal cell cycle exit and neuronal differentiation stemming from a failure in USP37-dependent stabilization of its target, the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKI)-p27. This finding suggested a tumor suppressive function for USP37. Interestingly, the current study also uncovered Raptor, a component of the mTORC1 complex, as a novel target of USP37. Under conditions of low-USP37 expression, reduced Raptor stability and mTORC1 activity caused a decline in phosphorylation of 4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP1) and increased its interaction with eukaryotic elongation factor 4E (eIF4E), which is known to inhibit CAP-dependent translation initiation. Surprisingly, a subset of patients with SHH-driven medulloblastomas with elevated expression of USP37 and the Glioma-associated Oncogene 1 (GLI1), also exhibited poor outcomes. Using genetic and biochemical analyses, we showed that USP37-mediated stabilization of GLI1, a terminal effector of SHH signaling, increases pathway activity and upregulates expression of its target oncogene product, CCND1, to drive cell proliferation. These data indicate that USP37 elevation in SHH-driven medulloblastomas has the potential to promote non-canonical activation of SHH signaling. Overall, our findings suggest that USP37 may have context-specific oncogenic and tumor suppressive roles in medulloblastoma cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medulloblastoma (MB) is the most common malignant brain tumor of childhood, with over 500 new diagnoses each year [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Despite advances in the molecular stratification and understanding of tumor biology, standard of care relies on surgical resection, craniospinal radiation and chemotherapy [7, 9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. These are toxic to the normal developing brain and cause long-term quality of life issues and further, are ineffective in the setting of recurrence/metastasis [9,10,11,12,13,14,15, 20]. The 5-year survival for patients diagnosed with MBs is 66%, with molecular subgroups—Wingless (Wnt), Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), group 3, or group 4, serving as the main determinant of outcomes [1, 3, 8, 9, 11, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Patients with group 3 MBs have the worst prognosis, whereas those with SHH and group 4 tumors have intermediate outcomes [1, 3, 8, 9, 11, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. While deregulated chromatin remodeling is implicated in MB genesis [21, 26, 32, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49], there is also growing evidence of aberrant regulation of protein degradation in SHH-driven MBs [35, 36].

Our previous work implicated the Ubiquitin Specific Protease 37 (USP37)—a deubiquitylase (DUB) and a component of the proteasomal degradation machinery, in MB biology [35, 36]. DUBs catalyze the proteolytic removal of ubiquitin groups from proteins, resulting in changes to their stability, subcellular localization, or function [50,51,52,53,54]. They oppose the functions of enzymes (E1-3), which coordinate the addition of ubiquitin moieties to proteins [55,56,57]. Previously, we found that in SHH-driven MB cells with RE1 silencing transcription factor (REST) elevation, USP37 downregulation prevented the stabilization of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKI)-p27 and maintained cell proliferation [35]. Pharmacological targeting of G9a histone methyltransferases upregulated USP37 expression and reduced tumor formation of low-USP37 MBs, suggesting an epigenetic basis for USP37 downregulation in MBs [36]. At approximately the same time, work from the Dixit group demonstrated a role for USP37 in controlling S phase entry through its regulation of cyclin A stability in non-neural cells [58]. Since these initial reports, research from other groups has revealed the importance of USP37 in the regulation of DNA replication and cell cycle [35, 59, 60]/cell proliferation [61] in addition to functions in receptor signal transduction [62], homologous recombination [63], DNA damage repair [64], cell migration [65], autophagy [66], epithelial to mesenchymal transition [67] and resistance to chemotherapy [68].

In the current study, we identify Raptor and GLI1 as novel USP37 targets in SHH-MBs and also suggest that USP37 may have context-specific oncogenic roles in addition to its previously described tumor suppressive function in these tumors [35]. We show that REST elevation and low USP37 results in reduced stability of Raptor, a component of the mTORC1 complex, and a regulator of protein translation. In the context of high USP37 expression, we found increased GLI1 protein levels and USP37-dependent GLI1 ubiquitination and protein stabilization. These data suggest a REST-context specific role for USP37 in the regulation of protein translation and in the non-canonical activation of SHH signaling in SHH-MBs. Consistent with these findings, USP37 loss in the context of high-REST expression, as well as USP37 elevation in the background of high-glioma-associated oncogene 1 (GLI1) levels, were both found to be correlated with poor outcomes for patients with SHH-MBs.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

Two publicly available MB patient’s datasets (GSE85217 and GSE124814) were used for gene expression analysis [69, 70]. Differential gene expression analysis was performed using the R2: Genomics Analysis and Visualization Platform (http://r2.amc.nl). A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. Gene ontology p-values were not corrected for multiple testing. Histopathological analyses was performed in paraffin embedded de-identified MB tumor sections (n = 33) by our collaborating neuropathologist.

Cell culture

293T and SHH-MB cell lines (DAOY, UW228, UW426, and ONS76) are used in this study. DAOY cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA). UW228 and UW466 cells were a kind gift of Dr. John Silber at the University of Washington. ONS76 cells were purchased from Accegen, NJ, USA. All cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich), 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), and 1% sodium pyruvate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Patient-derived xenograft models

Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models (RCMB-18, 24 and 54) were a kind gift of Dr. Robert Wechsler-Reya (Columbia University). Serial transplantation of tumors was carried out in NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) by intracranial inoculation of tumor cells using a stereotactic device as described previously [48]. Housing, maintenance, and experiments involving mice were done in compliance with a protocol approved by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Our study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Animals

Generation of Ptch+/−/RESTTG is described in an earlier [48]. The hREST transgene expression was induced by intraperitoneal (ip) injections of (100 µl of 2 mg/ml) tamoxifen (Cat# T5648, Sigma-Aldrich) on post-natal (P) days 2, 3 and 4. Moribund animals were euthanized, and brains were harvested for further analysis. All experiments were compliant with institutional IACUC guidelines and in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse brain tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin phosphate for 48 h (h) and embedded in paraffin. 8 µm thick sections were used for histological analysis using a Gemini AS Automated Stainer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After overnight incubation with primary antibody at 4 °C, the sections were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody provided by either the ABC kit or the MOM kit (Vector Laboratories, CA, USA). For detection, VECTASTAIN® Elite® ABC-HRP Kit, Peroxidase (Cat# PK-6101, Vector Laboratories) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions and developed using the DAB Substrate Kit, Peroxidase (HRP) (Cat# SK-4100, Vector Laboratories) followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin. After dehydration and mounting, slides were visualized under a Nikon ECLIPSE E200 microscope mounted with an Olympus SC100 camera. The list of primary antibodies used for IHC is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Lentiviral infection and generation of stable cell lines

Embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were co-transfected with either a control or the gene of interest along with packaging plasmid (PAX2) and envelope plasmid (MD2). Lentiviral particles were collected 48 h post-transfection. MB cells were transduced with the collected viral supernatant in the presence of Polybrene (8 μg/mL) and incubated for 48 h. Infected cells were then cultured in medium containing 2 μg/mL puromycin for up to 1 week for selection.

Cycloheximide (CHX) chase assay

SHH-MB cell lines were treated with CHX alone for varying lengths of time (0–240 min) to assess changes in protein levels. To show proteasomal control of protein stability, rescue experiments were conducted, where cells were co-treated with CHX and MG132 for 240 min. Following the above treatment(s), cells were harvested and lysed using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. Protein lysates were quantified and analyzed by Western blotting to evaluate the dynamics of protein degradation.

Western blot analyses

Cell lysates were prepared in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and protease/phosphatase inhibitors) and processed for Western blotting as described previously [40] using primary antibodies listed in Supplementary Table S1 followed by HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies. SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Cat#34075, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Western Lightning Plus-ECL, Enhanced Chemiluminescence Substrate (Cat# 50-904-9325, Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) were used to develop the blot and detected using Kodak Medical X-Ray Processor 104 (Eastman Kodak Company) or ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Images were analyzed using Image Lab software version 5.2.1 (Bio-Rad).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Cell pellets were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in mild lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Cat# 78429, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and phosphatase inhibitor (Sigma) and sonicated. Lysates were incubated with control mouse IgG, anti-USP37 (Cat# A300-927A, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-4EBP1 (Cat# 9644, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA), anti-eIF4E (Cat# 2067, Cell Signaling Technology) primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and then incubated with Pierce™ Protein A/G UltraLink™ Resin (Cat# 53132, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1.5 h at 4 °C. After four washes with lysis buffer, beads were boiled in loading buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and analyzed by Western blotting.

In vitro deubiquitination (DUB) assay

293T cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3-Myc3-Raptor/ pcDNA3-6XHis-GLI1 and HA-Ub or with pDEST26-FLAG-HA-USP37, FLAG-HA-USP37C350S or FLAG-HA-USP1 using jetPRIME (Polyplus, NY, USA). Cells were treated with 20 mM MG132 for 6 h prior to lysis. HA-Ub-Myc-Raptor and HA-Ub-6XHis-GLI1 substrate were purified using EZ view Red Anti-c-Myc Affinity Gel (Cat# E6654, Millipore Sigma) and Ni-NTA Agarose (Cat # R90101, Thermo Fisher Scientific), respectively. Deubiquitinase (DUBs: USP37, USP37C350S or USP1) were immunopurified using anti-FLAG M2 beads (Cat# A2220, Millipore Sigma) and eluted with FLAG peptide (Cat# HY-P0319, MedChem Express, NJ, USA). For DUB assays, equal amounts of substrates and purified DUBs were incubated for 8 h at 37 °C in the presence or absence of 15mM N-ethyl maleimide (NEM). Reactions were terminated by boiling in 2X Laemmli buffer and analyzed by Western blotting.

In vivo DUB assay

MB cells were transiently transfected with plasmids expressing (Flag-HA-USP37WT and Flag-HA-USP37C350S (Addgene, MA, USA). Cells were treated with 20 mM MG132 for 6 h prior to lysis. Samples were heat-denatured and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-Raptor (Cat# 2280, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-GLI1 (Cat# ab134906, Abcam, MA, USA), anti-FLAG (Cat# F1804, Millipore Sigma) and anti-Ubiquitin (Cat# 3933, Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), derived from at least three independent biological replicates. Comparisons of means between groups were conducted using unpaired Student’s t tests. For survival analysis, the Kaplan–Meier method was employed, and statistical significance between survival curves was assessed using the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. To analyze transcriptomic data from MB patients, Welch’s t test was used to account for unequal variances and sample sizes. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05, and results are denoted as: ****p < 0.0001, ***p = 0.0001–0.001, **p = 0.001–0.01, *p = 0.01–0.05, ns = not significant.

Results

Low- and high-USP37 expression in SHH-MBs is correlated with poor patient outcomes

Our previous work reported USP37 as a novel target of REST in SHH-MBs and also studied its expression in MB cell lines compared to normal cerebella [35, 36]. Here, we assessed the levels of USP37 in human MB samples (n = 33) (Fig. 1A). Samples were graded as negative (-) or positive (+/++/ +++/ ++++) for USP37 expression (Fig. 1A). Approximately, 33.3% of the samples were negative for USP37, whereas weak and focal staining (+) was noted in 30% of the samples. Weak diffuse and multifocal focal staining (++) was noted in 6.7% samples (Fig. 1A, B). The remaining 30% of samples exhibited strong expression of USP37 (23.3% - strong and focal staining (+++) and (6.7% - strong diffuse or focal (++++)) (Fig. 1A, B). Further, samples with negative or weak expression of USP37 (-/+/++) exhibited high levels of REST (++/+++/++++), while samples with high USP37 (+++/++++) were negative or expressed low levels of REST (-/+) (Fig. 1C).

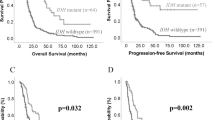

A Human MB samples (n = 33) were stained with anti-USP37 antibodies and graded on a scale from (-) to (++++) based on the level of USP37 expression (magnification: 40×). B Quantitation of data shown in (A) to show the distribution of tumors with different grades and patterns of USP37 staining. C Graphical representation of data from (A) and (B) to show the inverse correlation between REST and USP37 levels. Each dot represents a tumor. Significance and correlation were measured using the unpaired t-test and Pearson correlation coefficient (r = 0.478 and P value = <0.0001). D USP37 gene expression in a microarray data set (GSE85217) [69] of human SHH- MB samples. Hierarchical clustering based on the expression of neuronal differentiation markers divided the SHH-type MB patient samples into six distinct clusters [48]. Each dot corresponds to an individual patient. Statistical significance was assessed using Welch’s t-test. E Kaplan–Meier plot to demonstrate significant differences in the overall survival of SHH-MB patients divided into four cohorts based on the relative expression of REST and USP37 in their tumors (GSE85217) [69]. Statistical significance between survival curves was assessed using the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. F Pathway analysis to show significantly enriched pathways in tumors with high-REST/low-USP37 expression relative to samples with low-REST/high-USP37 expression using the GSE124814 dataset [70].

Transcriptomic data from MB patient samples revealed that USP37 levels were significantly lower in WNT, SHH and group 3 tumors compared to group 4 samples (Fig. S1A). Since our previous work implicated USP37 in SHH-MB pathology [35], we further investigated USP37 mRNA expression in the six differentiation-based clusters of SHH-MB patients described in our earlier studies [48, 69]. As expected, a significant reduction in USP37 expression was observed in clusters 2 and 5, which we previously showed to exhibit elevated REST expression and to be associated with poor outcomes (Fig. 1D). Kaplan Meier analyses confirmed that SHH-MB patients with high-REST/low-USP37 (n = 69) did indeed exhibit poor survival compared to patients with high-REST/high-USP37 (n = 27) and low-REST/low-USP37 (Fig. 1E). Unexpectedly, a cohort of SHH-MB patients with low-REST/high-USP37 (n = 19) in their tumors also exhibited poor outcomes (Fig. 1E). Further evaluation of the high-REST/low-USP37 and low-REST/high-USP37 cohorts of patients from the GSE124814 and GSE85217 datasets by pathway analyses revealed a significant enrichment of processes known to regulate cerebellar and hind brain development, including those regulating proliferation and maintenance of stem-cells and neuronal precursor cells, neurogenesis, and neuronal differentiation, Smoothened, Wnt and Hippo signaling (Fig. 1F and S1B). Interestingly, pathways which we previously discovered as REST-regulated, such as vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, hypoxia, cell-cycle and cell migration were enriched in the high-REST/low-USP37 cohort of patient samples compared to the low-REST/high-USP37 group (Figs. 1F and S1B). Apoptosis, protein translation, and mTOR were also differentially enriched in those two patient cohorts (Fig. 1F).

Animal models of SHH-MBs express variable levels of USP37 and REST

Immunohistochemical staining of patient-derived orthotropic xenograft (PDOXs) sections of SHH-MB tumors was performed to assess the levels of USP37 and REST (Fig. 2A). Of the four PDOX tumors, two showed strong Ki67 staining, while all four showed some positivity for TUBB3. Strong REST staining was observed in all four samples. Varying levels of USP37 staining were observed in the tumors, with RCMB-018 showing minimal staining and Med1712 exhibiting maximum cytoplasmic USP37 expression among the four samples (Fig. 2A). Cerebellar sections of Ptch+/-/RESTTG animals bearing tumors were also histologically analyzed, which revealed strong Rest staining as expected (Fig. 2B). Usp37 was low in two of the three samples studied (Fig. 2B).

Raptor is a novel target of USP37

In previous work by Dobson et al., we found that REST elevation in SHH-MB tumors to correlate with AKT activation as measured by its phosphorylation at Ser473 (pAKTSer473), a modification brought about by the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) [48]. Western blotting was used to confirm these findings in human SHH-MB cell lines expressing varying levels of REST and USP37 (Figs. S2A and 3A). As shown in Fig. 3A, cells with higher levels of REST (293 and DAOY) had higher p-AKTSer473 levels and that of its known targets p-GSK-3βSer9 and p-p27Thr157 compared to lower REST expressing cell line (UW228) [71, 72]. Total GSK-3β and Actin were included as controls (Fig. 3A). p27 levels were lower in DAOY cells consistent with our previous report showing reduced USP37 levels prevented the stabilization of the cell cycle regulatory protein [35]. In line with this finding, the kinase activity of Rictor was higher in 293 and DAOY cells compared to UW228 and UW426 cells as measured by reduction in the levels of the Thr1135 phosphorylation, an event known to inhibit Rictor activity [73, 74] (Fig. 3B). Total Rictor as well as MLST8 levels were not different in these cells (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, mTOR expression was lower in UW228 cells whereas expression of mSIN1, a structural component of the mTORC2 complex, was lower in UW228 and UW426 cells compared to DAOY and 293 cells (Fig. 3B). β-actin was used as the loading control (Fig. 3B). These results show that REST elevation is associated with increased mTORC2 complex activity in some SHH-MB cells.

Western blot analyses to assess levels of A AKT, GSK3β, and p27 and their respective phosphorylated forms in 293 and different MB cell lines with varying levels of REST, B mTORC2 components -p-Rictor, Rictor, mTOR, mLST8, and mSIN1 in SHH-MB cell lines with varying levels of REST, and C mTORC1 components - Raptor p-Raptor, PRAS40, Deptor, and the mTORC1 target - 4EBP1 and its phosphorylated form. D Western blot analysis to demonstrate post-translation and proteasomal control of Raptor in DAOY cells following treatment with cycloheximide (CHX) alone or in combination with the proteasome inhibitor, MG132 (shown by *). E Co-immunoprecipitation assay using control IgG or anti-USP37 antibodies followed by Western blotting to assess interaction between USP37 and mTORC1/2 components. Input shows 2% of total lysate. F In vivo DUB assay using transiently transfected FLAG (Fl)-tagged wildtype (WT) USP37 and mutant USP37 (USP37C350S) to study longitudinal changes in endogenous Raptor levels in DAOY cells. G In vitro DUB assay was done by co-incubation of purified MYC tagged-Ub-Raptor with Flag-WT-USP37 (lane 2), Flag-WT-USP37 in the presence of NEM (lane3), Flag-USP37C350S (lane 4) and Flag-USP1 (lane 5). The reaction containing MYC tagged-Ub-Raptor substrate alone is included as a control (lane 1). IHC to show Raptor expression in cerebellar sections of mice with H human SHH-MB PDOX tumors and I Ptch+/−/RESTTG tumors (scale bar: 20 µm). Statistical data are presented for three independent biological replicates as the means ± SDs. ns = non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 by Student’s t test.

AKT signaling is also known to negatively control mTORC1 activity. Indeed, Western blot analyses revealed lower mTORC1 activity in DAOY cells compared to UW228 and UW426 cells based on levels of phosphorylated 4EBP1, although total 4EBP1 levels were not different between these cells (Fig. 3C). Deptor, a component of both mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes, was absent in UW228 cells and lower in DAOY cells compared to 293 and UW426 cells (Fig. 3C). PRAS40 levels were similar between the cells (Fig. 3C). However, Raptor levels were significantly reduced in DAOY cells and was also associated with higher levels of the inhibitory Ser792 phosphorylation and a laddering pattern of migration, suggestive of post-translational modification such as ubiquitination [75]. A significant decrease in Raptor levels in DAOY cells following treatment with cycloheximide (CHX) suggested that its expression is post-transcriptionally controlled in SHH-MB cells (Fig. 3D). Further, co-treatment with the proteasome inhibitor, MG132, countered the reduction in Raptor levels suggesting that Raptor may be subjected to ubiquitin-mediated proteasome degradation (Fig. 3D). Other mTORC1 components did not reveal a similar MG132-dependent change in levels (Fig. S2B). The CHX-induced reduction in Raptor levels, along with its reversal upon co-treatment with MG132, was also validated in ONS76 cells (Fig. S2C). Immunoprecipitation assays were performed following co-transfection of DAOY cells with plasmids expressing Myc-Raptor and HA-Ubiquitin. Pull down with anti-HA antibody revealed strong ubiquitination of Raptor (Fig. S2D).

As a first step in investigating if the stability of Raptor is regulated by USP37, we performed co-immunoprecipitation assays using anti-USP37 antibody to demonstrate an interaction between endogenous USP37 and components of mTORC1 and mTORC2 in MB cells (Fig. 3E). Strong interaction between USP37 and Raptor was observed, but not between USP37 and other components of the mTORC complex such as Rictor, Deptor, mTOR, pRAS40, and mSIN1 (Fig. 3E). Studies with ONS76 cells also confirmed the interaction between USP37 and Raptor (Fig. S2E). Next, we assessed the stability of Raptor in response to USP37 overexpression. In vivo DUB assays confirmed an increase in Raptor levels and a decrease in high-molecular-weight bands of Raptor following USP37 overexpression in DAOY cells and ONS76 cells (Figs. 3F and S2F). Raptor levels were not discernably different in cells overexpressing a catalytically inactive mutant of USP37 (USP37C350S) (Figs. 3F and S2F). We also performed in vitro DUB assay using purified tagged proteins to ask if USP37 directly deubiquitinates Raptor. Addition of USP37 to the reaction containing Myc-Ub-Raptor resulted in a significant increase in Raptor levels compared to that containing USP37 and a protease inhibitor N-ethyl maleimide (NEM) or USP37C350S or USP1 (Fig. 3G). Thus, these findings indicate that REST-dependent destabilization of Raptor is caused by reduction in USP37 levels. Immunohistochemical staining of SHH-MB PDOXs and Ptch+/-/RESTTG tumor sections was also carried out to demonstrate a positive correlation between USP37 and Raptor levels (Figs. 2A, B, 3H, I). Together, these data identify Raptor as a novel target of USP37.

REST and USP37 converge on the cellular cap-dependent protein translational machinery

USP37 overexpression-dependent increase in Raptor levels in MB cells was accompanied by an increase in phospho-4EBP1 (Fig. 4A). However, total 4EBP1 levels were unaffected (Fig. 4A). p27 levels were also increased under these conditions, as expected, and served as a positive control (Fig. 4A). Actin was used as a loading control (Fig. 4A). mTORC1 kinase controls protein translation initiation through phosphorylation of 4EBP1, which inhibits its binding with eIF4E and favors cap-dependent translation initiation (Fig. 4B) [76, 77]. As seen in Fig. 4A, C, USP37 overexpression in DAOY and ONS76 cells caused an increase in phospho-4EBP1 levels, and co-immunoprecipitation assays using anti-4EBP1 antibodies showed an USP37-dependent decrease in interaction between 4EBP1 and eIF4E. An increase in the phosphorylated form of 4EBP1 was also noted in the immunoprecipitate, validating the decreased interaction between 4EBP1 and eIF4E and confirming increased activation of mTORC1 complex under conditions of USP37 elevation (Fig. 4A, C). As expected, 4EBP1 did not interact with eIF4G, a scaffolding component of the translational initiation machinery (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that cap-dependent translation initiation may be favored under conditions of constitutive USP37 expression. In contrast, under conditions of REST overexpression, interaction between eIF4E and 4EBP1 was increased and that between IF4E and eIF4G was decreased, suggesting an inhibition of cap-dependent translation initiation (Fig. 4D).

A Western blotting to show changes in the levels of Raptor, 4EBP1, p-4EBP1 and p27 in DAOY and ONS76 MB cell lines with constitutive over expression of USP37. B Schema to illustrate expected effect of mTORC1 kinase activity on phosphorylation of 4EBP1 and its interaction with eIF4E. Phosphorylated 4EBP1 releases eIF4E, allowing its binding to the CAP structure of mRNA and thereby enabling canonical protein translation. Conversely, mTORC1 inactivity results in the binding of unphosphorylated 4EBP1 to eIF4E, preventing its association with the CAP structure of mRNA. This is expected to prevent canonical protein translation initiation and cause a potential shift to CAP-independent protein translation. Co-immunoprecipitation assays to study C interaction of 4EBP1 with eIF4E and eIF4G using control IgG or anti-4EBP1 antibody and D eIF4E with 4EBP1, p-4EBP1, and eIF4G using control IgG or anti-eIF4E antibody, in parental and isogenic USP37- and REST- overexpressing DAOY and ONS76 cells, respectively. Statistical data are presented for three independent biological replicates as the means ± SDs. ns = non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.0001 by Student’s t test.

USP37 promotes GLI1 stability

As shown in Fig. 1E, patients with high-REST/low-USP37 as well as low-REST/high-USP37 expression in their tumors exhibited poor survival. Enrichment of pathways associated with SHH signaling led us to investigate if the underlying mechanism may involve USP37-mediated regulation of one or more molecules driving SHH pathway activity. Based on a previous report that GLI1 is a target of USP37 in breast cancer cells - a non-neural cell type, we explored if a similar USP37-dependent stabilization of GLI1 and consequent hyperactivation of SHH signaling may drive SHH MB tumor growth [67]. Consistent with this possibility, patients with high-GLI1 expression, and low or high-USP37 expression, in their tumors exhibited poor overall survival (Fig. 5A). Pathways known to be controlled by GLI1 including apoptosis and cell migration, ciliary assembly, transport and organization, early-stage brain development, and development of metencephalon, hindbrain, cerebellum, and neuronal differentiation, were enriched in patient tumors with high GLI1 expression in the GSE124814 dataset (Fig. 5B). Immunohistochemical staining for GLI1 in SHH-MB PDOX brain sections showed higher USP37 levels to be associated with higher GLI1 protein levels (Figs. 2A and 5C). CCND1, a known GLI1 target, was also elevated in high USP37/high-GLI1 expressing tumors along with low levels of cleaved Caspase 3, indicating an increase in proliferation and decrease in apoptosis under these conditions (Fig. 5C). Tumor sections from Ptch+/- SHH-MB mice also showed a positive association between Usp37 and Gli1 protein levels (Figs. 2B and 5D).

A Kaplan–Meier plot to show a significant correlation between reduced overall survival of SHH-MB patients with high expression of USP37 and GLI1 in their tumors (GSE85217) [69]. Statistical significance was assessed using the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. B Bubble plot to show significantly enriched pathways in tumors with high-USP37/high-GLI1 compared to low-USP37/high-GLI1 expressing samples in the GSE124814 dataset [70]. IHC staining of cerebellar sections with C human SHH-MB PDOX and D Ptch+/− SHH-MB tumors (n = 3) for GLI1, CCND1 and Cleaved caspase3 and Usp37 and Gli1, respectively. (scale bar: 200 µm for H&E (D) and 20 µm for IHC).

Next, biochemical analyses were performed to investigate if GLI1 is a target of USP37 in MB cells. We first examined the expression of REST, USP37, and GLI1 across four SHH-MB cell lines (Fig. S3A). DAOY and UW228 cells, which have low USP37 expression, also exhibited reduced GLI1 levels. In contrast, ONS76 cells, with higher USP37 expression, demonstrated elevated GLI1 levels (Fig. S3A). Further, in ONS76 cells, GLI1 levels were markedly reduced following CHX treatment, but were restored upon co-treatment with MG132 suggesting that GLI1 is subjected to proteasomal degradation, likely in a ubiquitination-dependent process. (Fig. 6A). In UW228 cells, CHX treatment led to a reduction in GLI1 levels. Although co-treatment with MG132 significantly increased GLI1 levels compared to 240 h of CHX alone, the levels could not be restored to that in untreated cells (Fig. 6A). Next, co-immunoprecipitation assays were done to show a strong interaction of endogenous USP37 with GLI1 in UW228 and ONS76 cells (Fig. 6B). Overexpression of USP37 in both SHH-MB cell lines promoted a significant increase in the levels of GLI1 and its target, CCND1 (Fig. 6C). In vivo DUB assays showed an increased GLI1 levels at 16 and 24 h post-transient transfection of WT, but not the catalytically impaired USP37 (USP37C350S) mutant in ONS76 and UW228 cells (Figs. 6D and S3B). Anti-FLAG antibody was used to confirm expression of both USP37 transgenes (Figs. 6D and S3B). Finally, in vitro DUB assays were performed using tagged proteins affinity-purified from transiently transfected 293 cells to assess if GLI1 is a direct target of USP37. Incubation with WT USP37 caused a significant increase in GLI1 protein at the expected molecular weight of ~150 kDa (Fig. 6E). In contrast, incubation with USP37C530S, USP1 or WT-USP37 in the presence of NEM did not support GLI1 stabilization (Fig. 6E). The above data confirm that GLI1 protein level is controlled by USP37-mediated deubiquitination in SHH-MB cells.

A Western blot analyses to show changes in the levels of GLI1 in UW228 and ONS76 cells after treatment with CHX for 0 min to 240 min and co-treatment with CHX and MG132 for 240 min (*). B Co-immunoprecipitation assay using control IgG or anti-USP37 antibody to show interaction between endogenous USP37 and GLI1 proteins in UW228 and ONS76 cells. C Western blot analysis to demonstrate an increase in the levels of GLI1 and its target gene product, CCND1 in UW228 and ONS76 cells following overexpression of transiently transfected USP37. D In vivo DUB assay to show a longitudinal increase in GLI1 protein levels after transient expression of Fl-USP37WT but not with Fl- USP37C350S mutant proteins in ONS76 cells. Overexpressed USP37 proteins are shown using anti-FLAG antibody. E In vitro DUB assay was performed by co-incubation of purified HA-Ub-6XHis-GLI1 with Flag-WT-USP37 (lane 2), Flag-WT USP37 in the presence of NEM (lane3), Flag-USP37C350S (lane 4) and Flag-USP1 (lane 5). The reaction containing purified HA-Ub-6XHis-GLI1 alone is shown in lane 1. Statistical data are presented for three independent biological replicates as the means ± SDs. ns = non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 by Student’s t test.

Discussion

DUBs are a class of catalytic enzymes that remove ubiquitination moieties from proteins to regulate their stability and or function [78]. Deregulation of DUBs is linked to critical cellular processes such as cell cycle control, apoptosis, and DNA repair, contributing to the development and progression of various cancers [79, 80]. USP37 is a cysteine protease that has been reported to control biological processes such as chromosomal cohesion and mitotic progression, cell cycle progression, stemness and cancer cell therapeutic sensitivity, metastasis, DNA damage response and epithelial to mesenchymal transition [58, 60, 63, 65, 67, 68, 81]. Our previous work had implicated USP37 in the stabilization of the CDKi–p27 and showed that USP37 downregulation in REST-driven SHH-MBs drives cell proliferation and prevents cell cycle exit [35]. In follow up studies, we demonstrated that REST-associated G9a histone methyltransferase was involved in the epigenetically silencing of USP37 in the REST-high SHH-MB cell, DAOY [36]. Overall, these studies suggested a tumor suppressive role for USP37 in REST-driven SHH-MBs. However, in non-neural cells, USP37 was also shown to exhibit oncogenic properties [61, 62, 82, 83], which suggested that USP37 may have cell and context-specific tumor suppressive and oncogenic roles.

In the current study, the identification of Raptor as a novel target of USP37 links it to the mTORC1 complex, and through it to the regulation of protein translation and potential management of cellular energetics and metabolism [84,85,86]. mTORC1 directly controls protein translation through its kinase activity and phosphorylation of S6 kinase (S6K) and 4EBP1, and downregulation of their activity under conditions of low USP37 would be expected to significantly impact cap-dependent protein translation [85]. However, REST elevation in SHH-MB cells is associated with increased cell proliferation, which requires protein translation [39, 48]. This raises questions regarding how cancer cells meet the demand for new protein synthesis associated with rapidly dividing cells. A possible scenario is that in context of REST elevation and USP37 downregulation forces SHH-MB cells to switch to non-canonical cap-independent protein translation initiation mechanisms to meet the increased cellular demand for proteins necessary for stress adaptation and survival [87, 88]. Indeed, MB cells have been shown to employ internal ribosome entry site (IRES) elements to initiate protein translation without relying on the 5’ cap structure, and to selectively elevate the translation of oncoproteins essential for tumor cell growth and survival [89, 90]. However, additional studies are needed to demonstrate that indeed USP37-deficient cells rely on non-canonical translational initiation mechanisms, as well as identify the specific molecular mechanisms deployed under conditions of low mTORC1 activity.

Impaired mTORC1 complex activity is also known to reduce anabolic processes such as protein and lipid biosynthesis and decrease translation of mitochondrial proteins and biogenesis to modulate cellular energy production [85, 86]. Under these conditions, cells exhibit an increased reliance on catabolic and scavenging mechanisms such as autophagy for survival [91, 92]. In fact, in previous work we showed that REST elevation in SHH-MB cells upregulates HIF1α expression and autophagy [40]. Interestingly, in earlier work we also identified a role for REST in the phosphorylation of AKT, tumor cell infiltration and leptomeningeal dissemination [48]. AKT is also shown to modulate mTORC1 complex activity through TSC1/2 and PRAS40 [93, 94]. Thus, it is possible that REST elevation and consequent silencing of USP37 expression may allow the survival of infiltrative and metastatic tumor cells through engagement of the cap-independent protein translation machinery as well as co-opting catabolic processes. These data point to a role for USP37 in the adaptation of REST-driven SHH MBs to cell stress, allowing for cell survival.

In contrast, in the absence of perturbations in REST levels in SHH-MBs or when USP37 expression is elevated and GLI1 is stabilized in a USP37-dependent manner, the upregulation of GLI1 target oncogene product, CCND1 drives proliferation of SHH-MB cells [95]. Work from other groups has shown that GLI1 is subject to both transcriptional and post-translational control by ubiquitination [96,97,98,99]. Our findings are also consistent with work by Qin et al, which showed that USP37 mediated the increase in GLI1 stability in breast cancer cells [67]. Although not tested, it may also facilitate an auto feedback loop to increase GLI1 transcription. Here, USP37 appears to function as an oncogene. Paradoxically, when REST is elevated and USP37 is downregulated, and presumably GLI1 levels are reduced, SHH signaling continues to be maintained by mechanisms that are yet to be elucidated. GLI1 is one of three GLI transcription factors, and its functional overlap with GLI2 may help maintain SHH pathway activity. When GLI1 is downregulated, GLI2 may partially compensate due to its role as an important activator of SHH signaling, a topic of ongoing investigation in our group [100,101,102]. It is also important to note that USP37 is not the only GLI1-specific DUB and HAUSP/USP7, USP48 and USP21, which have been identified as GLI1 deubiquitinating enzymes in non-MB systems, and whether these compensate for USP37 loss to allow proliferation of REST-high SHH-MBs remains to be investigated [103,104,105]

This work also highlights the paradoxical duality of USP37 function in MBs. This is not unique to USP37 since multiple publications in the literature support the functional duality of proteins as tumor promoters or suppressors [106]. SHH-MBs tumors have their origins in cerebellar granule precursor cells (CGNPs), and potentially cells at different stages of neuronal lineage commitment [107, 108]. REST elevation in these different neuronal lineage commitment states may give rise to the clusters of SHH-MB cells described in Fig. 1D and create unique cellular contexts in which USP37 interaction with various substrate(s) may occur. Alternatively spliced isoforms of USP37 are also suggested to exist, and their preferential expression under normal or elevated REST expression conditions may be an additional avenue for context-specific USP37-substrate interactions, which is also being actively explored in our laboratory.

Our findings described here support a growing body of literature which suggest that non-canonical activation of GLI1 may turn on SHH pathway signaling independent of SMO activation [96, 109, 110]. Critically, tumors (including MBs), with non-canonical activation of GLI signaling are less sensitive to SMO inhibitors [111,112,113]. GLI inhibitors are under consideration for other cancers, yet targeting GLI proteins is thought to be challenging. GANT61, which interferes with GLI-DNA binding, is the most promising of GLI antagonists, but its clinical use is restricted by its pharmacological properties [114]. SRI-38832, a derivative of GANT61 is more potent but is not commercially available [115]. ATO, which is FDA-approved against promyelocytic leukemia, has shown GLI inhibition in mouse models of MB and basal cell carcinoma [116]. If effective, GLI inhibitors may have promise against USP37-high SHH-MBs. While G9a is involved in the silencing of USP37 expression, the mechanisms underlying UPS37 upregulation in SHH-MBs are unclear and defining this process may allow for further therapeutic advances. However, the duality of USP37 function in SHH-MBs (Fig. 7), which our work clearly highlights, must be taken into consideration while effective therapeutic strategies are being developed.

Under high REST conditions, USP37 is downregulated, leading to destabilization of Raptor and subsequent inactivation of mTORC1. This inactivation decreases cap-dependent protein translation initiation. Conversely, when USP37 levels are elevated, it stabilizes GLI1 protein to promote proliferation of SHH-MB cells.

Data availability

All transcriptomic analyses were performed using previously published datasets: GSE85217 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE85217) and GSE124814 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE124814).

References

Archer TC, Mahoney EL, Pomeroy SL. Medulloblastoma: molecular classification-based personal therapeutics. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14:265–73.

Aktekin EH, Kutuk MO, Sangun O, Yazici N, Caylakli F, Erol I, et al. Late effects of medulloblastoma treatment: multidisciplinary approach of survivors. Childs Nerv Syst. 2024;40:417–25.

Cho YJ, Tsherniak A, Tamayo P, Santagata S, Ligon A, Greulich H, et al. Integrative genomic analysis of medulloblastoma identifies a molecular subgroup that drives poor clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1424–30.

Zeltzer PM, Boyett JM, Finlay JL, Albright AL, Rorke LB, Milstein JM, et al. Metastasis stage, adjuvant treatment, and residual tumor are prognostic factors for medulloblastoma in children: conclusions from the Children’s Cancer Group 921 randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:832–45.

Van Ommeren R, Garzia L, Holgado BL, Ramaswamy V, Taylor MD. The molecular biology of medulloblastoma metastasis. Brain Pathol. 2020;30:691–702.

Spix C, Erdmann F, Grabow D, Ronckers C. Childhood and adolescent cancer in Germany-an overview. J Health Monit. 2023;8:79–93.

Korshunov A, Sahm F, Stichel D, Schrimpf D, Ryzhova M, Zheludkova O, et al. Molecular characterization of medulloblastomas with extensive nodularity (MBEN). Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136:303–13.

Garcia-Lopez J, Kumar R, Smith KS, Northcott PA. Deconstructing sonic hedgehog medulloblastoma: molecular subtypes, drivers, and beyond. Trends Genet. 2021;37:235–50.

Choi JY. Medulloblastoma: current perspectives and recent advances. Brain Tumor Res Treat. 2023;11:28–38.

Hammoud H, Saker Z, Harati H, Fares Y, Bahmad HF, Nabha S. Drug repurposing in medulloblastoma: challenges and recommendations. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2020;22:6.

Hovestadt V, Ayrault O, Swartling FJ, Robinson GW, Pfister SM, Northcott PA. Medulloblastomics revisited: biological and clinical insights from thousands of patients. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:42–56.

Leary SE, Olson JM. The molecular classification of medulloblastoma: driving the next generation clinical trials. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012;24:33–39.

Martin AM, Raabe E, Eberhart C, Cohen KJ. Management of pediatric and adult patients with medulloblastoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2014;15:581–94.

Rechberger JS, Toll SA, Vanbilloen WJF, Daniels DJ, Khatua S. Exploring the molecular complexity of medulloblastoma: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Diagnostics. 2023;13:2398.

Rosenberg T, Cooney T. Current open trials and molecular update for pediatric embryonal tumors. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2023;58:299–306.

Mynarek M, von Hoff K, Pietsch T, Ottensmeier H, Warmuth-Metz M, Bison B, et al. Nonmetastatic medulloblastoma of early childhood: results from the prospective clinical trial HIT-2000 and an extended validation cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2028–40.

Rutkowski S, von Hoff K, Emser A, Zwiener I, Pietsch T, Figarella-Branger D, et al. Survival and prognostic factors of early childhood medulloblastoma: an international meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4961–8.

von Bueren AO, von Hoff K, Pietsch T, Gerber NU, Warmuth-Metz M, Deinlein F, et al. Treatment of young children with localized medulloblastoma by chemotherapy alone: results of the prospective, multicenter trial HIT 2000 confirming the prognostic impact of histology. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:669–79.

Robinson GW, Rudneva VA, Buchhalter I, Billups CA, Waszak SM, Smith KS, et al. Risk-adapted therapy for young children with medulloblastoma (SJYC07): therapeutic and molecular outcomes from a multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:768–84.

Guerrini-Rousseau L, Abbas R, Huybrechts S, Kieffer-Renaux V, Puget S, Andreiuolo F, et al. Role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in metastatic medulloblastoma: a comparative study in 92 children. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22:1686–95.

Cooney T, Lindsay H, Leary S, Wechsler-Reya R. Current studies and future directions for medulloblastoma: A review from the Pacific Pediatric Neuro-oncology Consortium (PNOC) disease working group. Neoplasia. 2023;35:100861.

Bagchi A, Dhanda SK, Dunphy P, Sioson E, Robinson GW. Molecular classification improves therapeutic options for infants and young children with medulloblastoma. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2023;21:1097–105.

Fang FY, Rosenblum JS, Ho WS, Heiss JD. New developments in the pathogenesis, therapeutic targeting, and treatment of pediatric medulloblastoma. Cancers. 2022;14:2285.

Gajjar A, Robinson GW, Smith KS, Lin T, Merchant TE, Chintagumpala M, et al. Outcomes by clinical and molecular features in children with medulloblastoma treated with risk-adapted therapy: results of an international phase III trial (SJMB03). J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:822–35.

Hanz SZ, Adeuyan O, Lieberman G, Hennika T. Clinical trials using molecular stratification of pediatric brain tumors. Transl Pediatr. 2020;9:144–56.

Batora NV, Sturm D, Jones DT, Kool M, Pfister SM, Northcott PA. Transitioning from genotypes to epigenotypes: why the time has come for medulloblastoma epigenomics. Neuroscience. 2014;264:171–85.

Kool M, Koster J, Bunt J, Hasselt NE, Lakeman A, van Sluis P, et al. Integrated genomics identifies five medulloblastoma subtypes with distinct genetic profiles, pathway signatures and clinicopathological features. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3088.

Northcott PA, Buchhalter I, Morrissy AS, Hovestadt V, Weischenfeldt J, Ehrenberger T, et al. The whole-genome landscape of medulloblastoma subtypes. Nature. 2017;547:311–7.

Northcott PA, Shih DJ, Remke M, Cho YJ, Kool M, Hawkins C, et al. Rapid, reliable, and reproducible molecular sub-grouping of clinical medulloblastoma samples. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:615–26.

Taylor MD, Northcott PA, Korshunov A, Remke M, Cho YJ, Clifford SC, et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: the current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:465–72.

Archer TC, Ehrenberger T, Mundt F, Gold MP, Krug K, Mah CK, et al. Proteomics, post-translational modifications, and integrative analyses reveal molecular heterogeneity within Medulloblastoma subgroups. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:396–410.

Dubuc AM, Mack S, Unterberger A, Northcott PA, Taylor MD. The epigenetics of brain tumors. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;863:139–53.

Kumar R, Liu APY, Northcott PA. Medulloblastoma genomics in the modern molecular era. Brain Pathol. 2020;30:679–90.

Fang H, Zhang Y, Lin C, Sun Z, Wen W, Sheng H, et al. Primary microcephaly gene CENPE is a novel biomarker and potential therapeutic target for non-WNT/non-SHH medulloblastoma. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1227143.

Das CM, Taylor P, Gireud M, Singh A, Lee D, Fuller G, et al. The deubiquitylase USP37 links REST to the control of p27 stability and cell proliferation. Oncogene. 2013;32:1691–701.

Dobson THW, Hatcher RJ, Swaminathan J, Das CM, Shaik S, Tao RH, et al. Regulation of USP37 expression by REST-associated G9a-dependent histone methylation. Mol Cancer Res. 2017;15:1073–84.

Gopalakrishnan V. REST and the RESTless: in stem cells and beyond. Future Neurol. 2009;4:317–29.

Shaik S, Maegawa S, Gopalakrishnan V. Medulloblastoma: novel insights into emerging therapeutic targets. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2021;25:615–9.

Shaik S, Maegawa S, Haltom AR, Wang F, Xiao X, Dobson T, et al. REST promotes ETS1-dependent vascular growth in medulloblastoma. Mol Oncol. 2021;15:1486–506.

Singh A, Cheng D, Swaminathan J, Yang Y, Zheng Y, Gordon N, et al. REST-dependent downregulation of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor promotes autophagy in SHH-medulloblastoma. Sci Rep. 2024;14:13596.

Taylor P, Fangusaro J, Rajaram V, Goldman S, Helenowski IB, MacDonald T, et al. REST is a novel prognostic factor and therapeutic target for medulloblastoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:1713–23.

Gibson P, Tong Y, Robinson G, Thompson MC, Currle DS, Eden C, et al. Subtypes of medulloblastoma have distinct developmental origins. Nature. 2010;468:1095–9.

Roussel MF, Hatten ME. Cerebellum development and medulloblastoma. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2011;94:235–82.

Roussel MF, Stripay JL. Epigenetic drivers in pediatric medulloblastoma. Cerebellum. 2018;17:28–36.

Roussel MF, Stripay JL. Modeling pediatric medulloblastoma. Brain Pathol. 2020;30:703–12.

Zhang L, He X, Liu X, Zhang F, Huang LF, Potter AS, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics in medulloblastoma reveals tumor-initiating progenitors and oncogenic cascades during tumorigenesis and relapse. Cancer Cell. 2019;36:302–18.e307.

Wu X, Northcott PA, Dubuc A, Dupuy AJ, Shih DJ, Witt H, et al. Clonal selection drives genetic divergence of metastatic medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012;482:529–33.

Dobson THW, Tao RH, Swaminathan J, Maegawa S, Shaik S, Bravo-Alegria J, et al. Transcriptional repressor REST drives lineage stage-specific chromatin compaction at Ptch1 and increases AKT activation in a mouse model of medulloblastoma. Sci Signal. 2019;12:eaan8680.

Gopalakrishnan V, Tao RH, Dobson T, Brugmann W, Khatua S. Medulloblastoma development: tumor biology informs treatment decisions. CNS Oncol. 2015;4:79–89.

Amer-Sarsour F, Kordonsky A, Berdichevsky Y, Prag G, Ashkenazi A. Deubiquitylating enzymes in neuronal health and disease. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:120.

Basar MA, Beck DB, Werner A. Deubiquitylases in developmental ubiquitin signaling and congenital diseases. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28:538–56.

Clague MJ, Heride C, Urbe S. The demographics of the ubiquitin system. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:417–26.

Clague MJ, Urbe S, Komander D. Breaking the chains: deubiquitylating enzyme specificity begets function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:338–52.

Satija YK, Bhardwaj A, Das S. A portrayal of E3 ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitylases in cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:2759–68.

Mattern M, Sutherland J, Kadimisetty K, Barrio R, Rodriguez MS. Using ubiquitin binders to decipher the ubiquitin code. Trends Biochem Sci. 2019;44:599–615.

Rape M. Ubiquitylation at the crossroads of development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19:59–70.

Zenge C, Ordureau A. Ubiquitin system mutations in neurological diseases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2024;49:875–87.

Huang X, Summers Matthew K, Pham V, Lill Jennie R, Liu J, Lee G, et al. Deubiquitinase USP37 is activated by CDK2 to antagonize APCCDH1 and promote S phase entry. Mol Cell. 2011;42:511–23.

Hernández-Pérez S, Cabrera E, Amoedo H, Rodríguez-Acebes S, Koundrioukoff S, Debatisse M, et al. USP37 deubiquitinates Cdt1 and contributes to regulate DNA replication. Mol Oncol. 2016;10:1196–206.

Yeh C, Coyaud É, Bashkurov M, van der Lelij P, Cheung Sally WT, Peters Jan M, et al. The deubiquitinase USP37 regulates chromosome cohesion and mitotic progression. Curr Biol. 2015;25:2290–99.

Hong K, Hu L, Liu X, Simon JM, Ptacek TS, Zheng X, et al. USP37 promotes deubiquitination of HIF2α in kidney cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117:13023–32.

Kim J-O, Kim S-R, Lim K-H, Kim J-H, Ajjappala B, Lee H-J, et al. Deubiquitinating enzyme USP37 regulating oncogenic function of 14-3-3γ. Oncotarget. 2015;6:36551.

Typas D, Luijsterburg MS, Wiegant WW, Diakatou M, Helfricht A, Thijssen PE, et al. The de-ubiquitylating enzymes USP26 and USP37 regulate homologous recombination by counteracting RAP80. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6919–33.

Wu C, Chang Y, Chen J, Su Y, Li L, Chen Y, et al. USP37 regulates DNA damage response through stabilizing and deubiquitinating BLM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:11224–40.

Cai J, Li M, Wang X, Li L, Li Q, Hou Z, et al. USP37 Promotes lung cancer cell migration by stabilizing snail protein via deubiquitination. Front Genet. 2020;10:1324.

Kim MS, Kim SH, Yang SH, Kim MS. miR-4487 Enhances gefitinib-mediated ubiquitination and autophagic degradation of EGFR in non-small cell lung cancer cells by targeting USP37. Cancer Res Treat. 2021;54:445–57.

Qin T, Li B, Feng X, Fan S, Liu L, Liu D, et al. Abnormally elevated USP37 expression in breast cancer stem cells regulates stemness, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cisplatin sensitivity. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:287.

Qin T, Cui X-Y, Xiu H, Huang C, Sun Z-N, Xu X-M, et al. USP37 downregulation elevates the chemical sensitivity of human breast cancer cells to adriamycin. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18:325.

Cavalli FMG, Remke M, Rampasek L, Peacock J, Shih DJH, Luu B, et al. Intertumoral heterogeneity within medulloblastoma subgroups. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:737–54.

Weishaupt H, Johansson P, Sundström A, Lubovac-Pilav Z, Olsson B, Nelander S, et al. Batch-normalization of cerebellar and medulloblastoma gene expression datasets utilizing empirically defined negative control genes. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:3357–64.

Hermida MA, Dinesh Kumar J, Leslie NR. GSK3 and its interactions with the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling network. Adv Biol Regul. 2017;65:5–15.

Fujita N, Sato S, Katayama K, Tsuruo T. Akt-dependent phosphorylation of p27Kip1 promotes binding to 14-3-3 and cytoplasmic localization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28706–13.

Dibble CC, Asara JM, Manning BD. Characterization of rictor phosphorylation sites reveals direct regulation of mTOR complex 2 by S6K1. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5657–70.

Julien L-A, Carriere A, Moreau J, Roux PP. mTORC1-Activated S6K1 phosphorylates rictor on threonine 1135 and regulates mTORC2 signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:908–21.

Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS, et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30:214–26.

Siddiqui N, Tempel W, Nedyalkova L, Volpon L, Wernimont AK, Osborne MJ, et al. Structural insights into the allosteric effects of 4EBP1 on the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E. J Mol Biol. 2012;415:781–92.

Marcotrigiano J, Gingras A-C, Sonenberg N, Burley SK. Cap-dependent translation initiation in eukaryotes is regulated by a molecular mimic of eIF4G. Mol Cell. 1999;3:706–16.

Liang X-W, Wang S-Z, Liu B, Chen J-C, Cao Z, Chu F-R, et al. A review of deubiquitinases and their roles in tumorigenesis and development. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1204472.

Liu F, Chen J, Li K, Li H, Zhu Y, Zhai Y, et al. Ubiquitination and deubiquitination in cancer: from mechanisms to novel therapeutic approaches. Mol Cancer. 2024;23:148.

Sun T, Liu Z, Yang Q, Sun T, Liu Z, Yang Q. The role of ubiquitination and deubiquitination in cancer metabolism. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:146.

Wu L, Zhao N, Zhou Z, Chen J, Han S, Zhang X, et al. PLAGL2 promotes the proliferation and migration of gastric cancer cells via USP37-mediated deubiquitination of Snail1. Theranostics. 2021;11:700.

Yang W-C, Shih H-M, Yang W-C, Shih H-M. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP37 regulates the oncogenic fusion protein PLZF/RARA stability. Oncogene. 2013;32:5167–75.

Pan J, Deng Q, Jiang C, Wang X, Niu T, Li H, et al. USP37 directly deubiquitinates and stabilizes c-Myc in lung cancer. Oncogene. 2015;34:3957–67.

Zhang Y, Nicholatos J, Dreier JR, Ricoult SJH, Widenmaier SB, Hotamisligil GS, et al. Coordinated regulation of protein synthesis and degradation by mTORC1. Nature. 2014;513:440–3.

Panwar V, Singh A, Bhatt M, Tonk RK, Azizov S, Raza AS, et al. Multifaceted role of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway in human health and disease. Signal Trans Target Ther. 2023;8:375.

Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell. 2017;168:960–76.

Mahé M, Rios-Fuller T, Katsara O, Schneider RJ. Non-canonical mRNA translation initiation in cell stress and cancer. NAR Cancer. 2024;6:zcae026.

Walters B, Thompson SR. Cap-independent translational control of carcinogenesis. Front Oncol. 2016;6:128.

Rivero-Hinojosa S, Lau LS, Stampar M, Staal J, Zhang H, Gordish-Dressman H, et al. Proteomic analysis of Medulloblastoma reveals functional biology with translational potential. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018;6:48.

Kuzuoglu-Ozturk D, Aksoy O, Schmidt C, Lea R, Larson JD, Phelps RRL, et al. N-myc–mediated translation control is a therapeutic vulnerability in medulloblastoma. Cancer Res. 2023;83:130–40.

Deleyto-Seldas N, Efeyan A. The mTOR–autophagy axis and the control of metabolism. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:655731.

Rabanal-Ruiz Y, Otten Elsje G, Korolchuk Viktor I. mTORC1 as the main gateway to autophagy. Essays Biochem. 2017;61:565–84.

Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan K-L, Inoki K, et al. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–57.

Dibble CC, Manning BD, Dibble CC, Manning BD. Signal integration by mTORC1 coordinates nutrient input with biosynthetic output. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:555–64.

Doheny D, Manore SG, Wong GL, Lo H-W. Hedgehog signaling and truncated GLI1 in cancer. Cells. 2020;9:2114.

Sigafoos AN, Paradise BD, Fernandez-Zapico ME. Hedgehog/GLI signaling pathway: transduction, regulation, and implications for disease. Cancers. 2021;13:3410.

Chai JY, Sugumar V, Alshawsh MA, Wong WF, Arya A, Chong PP, et al. The role of smoothened-dependent and -independent hedgehog signaling pathway in tumorigenesis. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1188.

Zhang Q, Jiang J, Zhang Q, Jiang J. Regulation of hedgehog signal transduction by ubiquitination and deubiquitination. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:13338.

Niewiadomski P, Niedziółka SM, Markiewicz Ł, Uśpieński T, Baran B, Chojnowska K. Gli proteins: regulation in development and cancer. Cells. 2019;8:147.

Jing J, Wu Z, Wang J, Luo G, Lin H, Fan Y, et al. Hedgehog signaling in tissue homeostasis, cancers and targeted therapies. Signal Trans Target Ther. 2023;8:315.

Tolosa EJ, Fernandez-Barrena MG, Iguchi E, McCleary-Wheeler AL, Carr RM, Almada LL, et al. GLI1/GLI2 functional interplay is required to control Hedgehog/GLI targets gene expression. Biochem J. 2020;477:3131–45.

Bai CB, Auerbach W, Lee JS, Stephen D, Joyner ALGli2. but not Gli1, is required for initial Shh signaling and ectopic activation of the Shh pathway. Development. 2002;129:4753–61.

Zhou Z, Yao X, Li S, Xiong Y, Dong X, Zhao Y, et al. Deubiquitination of Ci/Gli by Usp7/HAUSP regulates hedgehog signaling. Dev Cell. 2015;34:58–72.

Zhou A, Lin K, Zhang S, Ma L, Xue J, Morris SA, et al. Gli1-induced deubiquitinase USP48 aids glioblastoma tumorigenesis by stabilizing Gli1. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:1318–30.

Heride C, Rigden DJ, Bertsoulaki E, Cucchi D, Smaele ED, Clague MJ, et al. The centrosomal deubiquitylase USP21 regulates Gli1 transcriptional activity and stability. J Cell Sci. 2016;129:4001–13.

Castel P, Rauen KA, McCormick F, Castel P, Rauen KA, McCormick F. The duality of human oncoproteins: drivers of cancer and congenital disorders. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:383–97.

Smit MJ, Martini TEI, Armandari I, Bočkaj I, Zomerman WW, de Camargo Magalhães ES, et al. The developmental stage of the medulloblastoma cell-of-origin restricts Sonic hedgehog pathway usage and drug sensitivity. J Cell Sci. 2022;135:jeb258608.

Gold MP, Ong W, Masteller AM, Ghasemi DR, Galindo JA, Park NR, et al. Developmental basis of SHH medulloblastoma heterogeneity. Nat Commun. 2024;15:270.

Jenkins D. Hedgehog signalling: emerging evidence for non-canonical pathways. Cell Signal. 2009;21:1023–34.

Pietrobono S, Gagliardi S, Stecca B. Non-canonical hedgehog signaling pathway in cancer: activation of GLI transcription factors beyond smoothened. Front Genet. 2019;10:556.

Queiroz KC, Spek CA, Peppelenbosch MP. Targeting Hedgehog signaling and understanding refractory response to treatment with Hedgehog pathway inhibitors. Drug Resist Updat. 2012;15:211–22.

Singh BN, Fu J, Srivastava RK, Shankar S. Hedgehog signaling antagonist GDC-0449 (Vismodegib) inhibits pancreatic cancer stem cell characteristics: molecular mechanisms. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27306.

Swiderska-Syn M, Mir-Pedrol J, Oles A, Schleuger O, Salvador AD, Greiner SM, et al. Noncanonical activation of GLI signaling in SOX2(+) cells drives medulloblastoma relapse. Sci Adv. 2022;8:eabj9138.

Agyeman A, Jha BK, Mazumdar T, Houghton JA, Agyeman A, Jha BK, et al. Mode and specificity of binding of the small molecule GANT61 to GLI determines inhibition of GLI-DNA binding. Oncotarget. 2014;5:05–31.

Zhang R, Ma J, Avery JT, Sambandam V, Nguyen TH, Xu B, et al. GLI1 inhibitor SRI-38832 attenuates chemotherapeutic resistance by downregulating NBS1 transcription in BRAFV600E colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:241.

Beauchamp EM, Ringer L, Bulut G, Sajwan KP, Hall MD, Lee Y-C, et al. Arsenic trioxide inhibits human cancer cell growth and tumor development in mice by blocking Hedgehog/GLI pathway. J Clin Investig. 2011;121:148–60.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by grants through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (5R01NS079715) and the Addis Faith Foundation to VG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS, DC, ARH, and VG designed experiments and analyzed data. AS, DC, ARH, TD, YY, and RH performed experiments. VR provided neuropathology support. AS, ARH, TD and VG wrote the manuscript. VG provided funding support.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods in this study were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations as indicated below. Histopathological analyses of SHH-MB tumor sections were performed by Dr. Veena Rajaram (collaborating neuropathologist) at UT Southwestern Medical Center. MB samples were collected under the auspices of the Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocol STU 022011-081 from patients enrolled in clinical trials following receipt of informed consent. Samples were de-identified prior to use for immunohistochemical analyses. For experiments involving mice, housing, maintenance, and research methods were done in compliance with a protocol approved by the UT MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)-approved protocol #00001080 guidelines. Our study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, A., Cheng, D., Haltom, A.R. et al. Identification of Raptor and GLI1 as USP37 substrates highlight its context-specific function in medulloblastoma cells. Oncogene 45, 521–533 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-025-03651-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-025-03651-2