Abstract

Background

Intrauterine blood transfusions (IUBTs) are critical for treating fetal anemia but may expose fetuses to toxic metals. This study assessed mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and arsenic (As) levels in red blood cell (RBC) transfusion bags used during pregnancy, examined metal exposure in maternal and cord blood, and evaluated fetal health risks.

Methods

Thirty pregnant women who underwent intrauterine blood IUBTs were enrolled in this study. Metal concentrations were measured in one to nine transfusion bags for each participant. These bags contained 8–103 mL volumes and were administered between gestational weeks 18 and 35. We also tested the mothers’ blood for metal levels in the final stages of pregnancy and the umbilical cord blood at birth. The assessment utilized the intravenous reference dose (IVRfD) and the hazard index (HI) to evaluate the non-carcinogenic health risks these metals might pose to the fetus.

Results

Metals were detectable in almost all transfusion bags. The IVRfD was exceeded for Hg in 16 fetuses, Cd in 8 fetuses, Pb in 30 fetuses, and As in 1 fetus. Significant correlations were found between the concentrations of Hg, Cd, and As in transfused RBCs and cord blood. No correlations were observed between these concentrations and maternal blood levels, except for Cd. The influence of multiple IUBTs was positively associated only with Cd levels in the cord (ß = 0.529, 95% confidence intervals (CI) between 0.180 and 0.879). The HI exceeded 1, indicating significant health risks, predominantly from Pb, followed by Hg and Cd.

Conclusion

The findings of this study highlight the significant risk of fetal exposure to toxic metals, mainly Pb, through IUBTs. This underscores the critical need for prescreening blood donors for toxic metals to minimize the potential for long-term adverse effects on the fetus. The research stresses the necessity of balancing the immediate benefits of IUBTs against the risks of toxic metal exposure, underscoring the importance of safeguarding fetal health through improved screening practices.

Impact

-

This study highlights the risk of toxic metal exposure through IUBTs, a treatment for fetal anemia.

-

Hg, Cd, Pb, and As levels were measured in transfusion bags and linked to fetal exposure through maternal and umbilical cord blood analysis.

-

The HI indicates significant Pb exposure risks, underscoring the need for mandatory blood donor screening.

-

Recommendations include shifting toward safer practices in managing fetal anemia to protect fetal health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An intrauterine blood transfusion (IUBT) is administered to fetuses suffering from anemia (a low red blood cell (RBC) count), predominantly due to Rhesus (Rh) blood group incompatibility between the mother and the fetus.1,2 While blood banks routinely screen blood for hazardous pathogens,3 potential contamination with pollutants, especially toxic metals like cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), arsenic (As), and mercury (Hg), has been somewhat overlooked. Several studies have highlighted that blood transfusions could serve as a source of exposure to heavy metals and other pollutants, posing a risk to sensitive recipients such as fetuses, premature infants, and neonates.4,5,6,7,8 Our recent research indicates that RBC transfusions may expose preterm neonates, especially those requiring multiple transfusions during their Neonatal Intensive Care Unit stay, to Pb and Hg.9 Consequently, some experts have advocated for screening transfusion blood for Pb because of its neurotoxic effects.

A study by Gehrie et al.10 noted that transfused RBCs could contain Pb concentrations more than 20 times higher than normal, posing a significant risk of pediatric Pb exposure. While Germany’s reference value for blood Pb was 7 µg/dL,11,12 the Human Biomonitoring Commission of the German Environment Agency discontinued this reference in 2010, citing Pb’s neurotoxicity and its classification as possibly carcinogenic to humans.13 Scientific evidence confirms that Pb levels below 3 µg/dL can impair cognitive function and induce maladaptive behavior in humans and animal models.14 Except for the study by Flack et al.,15 which reported substantial in utero exposure to Hg and Pb as early as 20 weeks of gestation following an IUBT procedure, further research in this area is scarce.

The current research aimed to evaluate the extent of fetal exposure to toxic metals through IUBTs by analyzing the residual blood from each transfusion bag received by the fetus throughout pregnancy. We directly measured fetal exposure to toxic metals in cord blood at birth and indirectly assessed it through maternal blood samples collected during the third trimester.

Research design and methodology

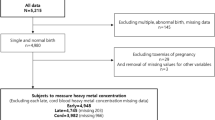

A prospective study was conducted from June 2020 to 2023 involving 30 pregnant women who underwent IUBTs at the Maternal-Fetal Therapy Unit, Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic of the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre (KFSH&RC). The indication for IUBTs primarily involved severe fetal anemia due to Rh alloimmunization, diagnosed through regular monitoring antibody titers and Doppler ultrasound measurements of the middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity (MCA-PSV). Elevated MCA-PSV values and hydrops fetalis observed on ultrasound are key indicators.

The transfused blood comprised packed red blood cells leuco-reduced and irradiated, O Rh D-negative, or cross-matched against the mother’s blood. It was obtained from cytomegalovirus-negative multiple donors and collected within 72 h of the procedure.

The volume of blood administered during IUBTs was determined on the basis of the estimated fetal weight and pre-transfusion hemoglobin level.

The gestational age at the time of IUBTs was calculated on the basis of the last menstrual period and expressed in weeks and days to ensure precise timing, as some fetuses received transfusions within a narrow gestational age span. During the third trimester (between 27 weeks and 6 days to 36 weeks), venous blood samples were collected from the study participants, and cord blood samples were obtained at delivery. Additionally, residual RBCs from the transfusion bags were collected. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the KFSH&RC (approval number RAC #2200007), and informed consent was obtained from each participant.

We collected 30 venous blood samples, 21 cord blood samples, and residual RBCs from 30 transfusion bags. The number of RBC transfusions received by the participants ranged from 1 to 9 during pregnancy. Residual RBCs from all transfusion bags were collected for 19 patients. However, for 11 patients, one or two bags were missed due to actions beyond our control, dependent on the attending nurse.

Eligibility criteria for participation included being 18 years or older, having a singleton pregnancy, planning to deliver at the KFSH&RC, residing in Riyadh for at least 1 year, and obtaining signed consent forms from both parents. Exclusion criteria encompassed significant chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, autoimmune disorders, and cardiac or renal issues, and women who developed preeclampsia during the study.

Collection and analysis of blood samples

Venous blood samples (5 mL) were collected from all pregnant women during the third trimester (between 27 weeks and 6 days to 36 weeks), and 4 mL of cord blood was obtained at delivery using ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey). A 200-µL portion of whole blood was then stored in 1.5 mL cryogenic vials (Corning Incorporated, NY) at −30 °C for later analysis of Hg, Cd, Pb, and As levels. Additionally, residual blood from each transfusion bag was collected post-RBC transfusion to assess concentrations of Hg, Cd, Pb, and As.

Each blood/RBC sample (50 µL) was diluted 50× with a specific diluent and measured using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (Perkin Elmer NexION®, 2000). Calibration curves for Hg, Cd, Pb, and As in blood showed linearity (R2 > 0.9994) across the range of 0.25–4.0 µg/L. Accuracy was validated using reference materials and spiked samples, achieving recoveries between 100 and 104.3% with relative standard deviations below 5%. ClinChek controls matched certified ranges. Method detection limits (MDLs) were determined as 0.002 µg/L, 0.044 µg/L, 0.0014 µg/L, and 0.0022 µg/L for Cd, Pb, As, and Hg, respectively. Complete method details can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Intravenous reference dose calculation

To enable the safety of toxic metal exposure to be calculated from blood transfusions, the intravenous reference dose (IVRfD) was calculated for each metal, following the procedures described in previous studies.15,16,17 Determining the IVRfD was crucial because it enabled the study to evaluate the potential health risks posed by the Hg, Cd, Pb, and As concentrations observed in RBC transfusion bags. This approach facilitated an informed understanding of the risks associated with exposure to metals during blood transfusions.

Risk assessment

We calculated the hazard index (HI) to estimate the potential non-cancer adverse health effects of toxic metals by summing the IVRfD values of each metal detected in the RBC transfusion bag.18 An HI value ≤1 indicates that the exposure is unlikely to result in non-cancer adverse health effects.18

Statistical analysis

Values within the text are presented as means, medians, minimums, and maximums. The relationship between the metal contents across different matrices was assessed using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. Moreover, differences in metal concentrations between cord and maternal blood were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. β regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated to evaluate the impact of the total number of IUBTs and their timing within the gestational period. All values below the MDL were substituted with half of the MDL value. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 20 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk), with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 30 women between 30 and 46 years received 1–9 IUBTs per fetus to treat fetal anemia secondary to Rh isoimmunization. The volume of each IUBT ranged from 8 to 103 mL and was administered on the basis of fetal weight, gestational age, pre-transfusion hemoglobin levels, hemoglobin drop between transfusions, and the presence of hydrops fetalis. The gestational age at the time of IUBTs ranged from 18 to 35 weeks. The median (range) pre-, mid-, and post-transfusion hemoglobin levels were 6.3 (1.2–14), 11.8 (2.8–17.7), and 14.6 (7.1–18.2) g/dL, respectively. Estimated fetal weight was not measured for all participants. Out of 141 instances of IUBT, fetal weight was recorded for only 37 cases, showing a median of 1450 g (range: 324–2654 g). These measurements exhibited a strong correlation (r = 0.959, p < 0.001) with the standard World Health Organization fetal weight chart for gestational age.19 Table 1 summarizes RBC transfusion parameters, demographic data, and toxic metal concentrations for all patients. Furthermore, patient-specific data are detailed in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Table S2).

Concentration of toxic metals in RBC transfusion bags

We analyzed 127 RBC transfusion bags and found that 98% of the bags contained detectable levels of Hg, 90% contained such levels of Cd and As, and 100% contained such levels of Pb. The median concentrations were as follows: Hg = 0.739 µg/L, Cd = 0.715 µg/L, Pb = 12.812 µg/L, and As = 0.483 µg/L. Furthermore, three bags were exposed to Hg levels above the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) reference value of 5.8 µg/L,20 and eight bags were found to be exposed to levels over 3.5 µg/L.21 Although no Cd levels were found to surpass the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)’s threshold of 5 µg/L,20,22 51 bags were found to exceed 1 µg/L, the typical level found in smokers,23 For Pb, while no samples surpassed the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s action level of 50 µg/L for children,24 four bags contained more than 35 µg/L,25 91 bags exceeded the recommended threshold of 10 µg/L for donor RBC units intended for pediatric use,10 and 125 bags exceeded the 5 µg/L interim reference level.26 For As, while the median concentration was below the level found in a previous study,9 18 bags exceeded the 1.4 µg/L threshold for children, while 10 surpassed the 2 µg/L threshold for adults.27

IVRfD assessment of toxic metals

Figure 1a–d illustrates the IVRfD of four metals to which fetuses are exposed during an IUBT. Each stacked bar represents the cumulative exposure for each fetus, corresponding to the IVRfD of each metal. The median IVRfD values for Hg, Cd, Pb, and As were 0.0319, 0.0271, 0.0543, and 0.0204 µg/kg, respectively. For Hg, although the median IVRfD was below the aforementioned level of 0.07 µg/kg,15 16 fetuses—aged from 19 weeks and 3 days to 33 weeks and 6 days—experienced Hg exposure above the IVRfD threshold of 0.095 µg/kg per transfusion.28 Notably, one fetus underwent four transfusions while five received two each, with median exposure levels of 0.140 µg/kg (range: 0.098–2.117 µg/kg). Cd exhibited a median IVRfD higher than the typical 0.01 µg/kg for preterm neonates.28 Moreover, eight fetuses exceeded the IVRfD benchmark of 0.1 µg/kg per transfusion,28 with one fetus undergoing four transfusions and three receiving two each. The median exposure levels were 0.113 µg Cd/kg body weight (range: 0.101–0.174 µg/kg). For Pb, the data indicated that fetuses aged between 18 weeks and 34 weeks and 6 days were subjected to 117 transfusions, with the Pb levels surpassing the 0.19 µg/kg threshold.15 Ten fetuses were exposed to 5–9 bags with elevated Pb levels. Finally, we calculated an IVRfD of 0.285 µg/kg body weight per transfusion for As.28 based on 95% gastrointestinal absorption.29 and an oral reference dose of 0.3 µg/kg body weight per day.30 Only one fetus exceeded this IVRfD level as it received a transfusion with 0.285 µg/kg body weight of As.

This figure presents stacked bar charts depicting the IVRfD for heavy metals in pregnant women undergoing multiple IUBTs. Panel (a) displays the data for Hg, panel (b) for Cd, panel (c) for Pb, and panel (d) for As. Red lines across each panel indicate the permissible IVRfD levels in µg/kg body weight, set at 0.095 for Hg, 0.1 for Cd, 0.19 for Pb, and 0.258 for As.

Heavy metals in maternal versus cord blood: concentrations and correlations

This study’s findings indicate significant differences in heavy metal concentrations between cord and maternal venous blood. Hg levels were found to be higher in cord blood (median: 0.515 µg/L; range: 0.051–2.029 µg/L) compared with maternal blood (median: 0.334 µg/L; range: 0.0011–1.075 µg/L; p = 0.034). Conversely, Cd concentrations were found to be approximately five times higher in maternal blood (median: 0.281 µg/L; range: 0.001–3.526 µg/L) than in cord blood (median: 0.079 µg/L; p-value = 0.031). Pb exhibited similar median levels in cord (4.352 µg/L) and maternal blood (4.254 µg/L) with no significant difference. Lastly, As levels were three times higher in maternal blood (median: 0.24 µg/L) than in cord blood (median: 0.093 µg/L; p-value = 0.092).

Furthermore, a correlation analysis revealed a strong association between Hg levels in RBC transfusions and cord blood (r = 0.803, p < 0.001) but not with maternal blood. However, Hg levels in cord and maternal blood were positively correlated (r = 0.57, p < 0.001). Moreover, moderate correlations were found for Cd levels between RBC transfusions and both types of blood (cord: r = 0.48, p = 0.032; maternal: r = 0.551, p < 0.001), with a positive correlation found between cord blood and maternal levels (r = 0.51, p = 0.022). By contrast, Pb levels displayed no significant correlations across RBC transfusions, cord blood, and maternal blood. Finally, As levels in RBC transfusions were positively correlated with cord blood (r = 0.504, p = 0.024) but exhibited no significant correlation with maternal venous As or between cord and maternal blood.

Impact of transfusion frequency and timing on metal levels

Table 2 outlines the impact of the total number of transfusions per mother/fetus dyad and their timing. Our analysis revealed a significantly positive association only between the total number of IUBTs and Cd levels in cord blood (ß = 0.529, 95% CI: 0.180 to 0.879). However, the timing of transfusions did not significantly influence metal levels.

Discussion

This study highlights critical concerns regarding fetal exposure to toxic metals through RBC transfusions, aligning with the findings of previous research. The notably high Hg, Cd, Pb, and As detection rates within RBC transfusion bags suggest that fetuses are particularly susceptible to these toxicants during vital developmental stages. This emphasizes the necessity of implementing stringent screening processes to detect and reduce the presence of toxic metals in blood donors before donation, thereby safeguarding fetal health.

Our findings highlight significant variability in Hg exposure levels among fetuses receiving RBC transfusions, with several instances surpassing the US EPA.20 and researcher-proposed safety thresholds.21 The exceedance of these thresholds, particularly the IVRfD,28 raises concerns about potential adverse health effects. The observed median exposure level of 0.140 µg Hg/kg body weight, higher than previously reported,15 suggests that certain fetuses are at increased risk, especially those undergoing multiple transfusions. This discrepancy with prior studies can be attributed to variations in transfusion practices or differences in the Hg content of transfused blood. Our results demonstrate a significant transfer of Hg via RBC transfusions into cord blood, suggesting efficient crossing through the placental barrier.31 This is supported by the strong correlation between Hg levels in RBC transfusions and cord blood. Additionally, the positive correlation between Hg levels in cord and maternal venous blood underscores a systemic circulation of Hg, typically in an organic form such as methylmercury,32 which is known for its high placental transfer efficiency.33 This highlights the potential risks to fetal health from Hg exposure during transfusions. Furthermore, the median Hg concentration in cord blood was notably higher than in maternal venous blood, a difference consistently observed in prior studies and has been attributed to the presence of high-affinity fetal-specific serum albumin proteins in the cord blood compared to maternal blood.34,35,36,37,38 Nevertheless, the median Hg levels observed in cord (0.51 µg/L) and maternal blood (0.334 µg/L) are lower than those reported in previous studies, specifically in cord blood (1.949 µg/L) and maternal blood (2.876 µg/L) from over a decade ago.34 Crucially, none of these levels exceeded the critical threshold value for Hg in blood.20

Our research confirms that fetuses are exposed to Hg through RBC transfusions, a matter that raises significant concerns due to the vulnerability of the study population. Given the cumulative nature of Hg, it is critical to minimize early-life exposure to prevent serious health complications. This is particularly important for preventing neurodevelopmental delays that may manifest later in life.39

Furthermore, our findings regarding Cd levels in transfusion bags were concerning. While these levels do not exceed OSHA’s highest safety thresholds,22 they surpass those typically observed in high-exposure populations such as smokers.23 This is particularly alarming given the sensitive developmental stage of the fetuses. Moreover, the median IVRfD for Cd was higher than previously reported levels for preterm neonates, indicating a potential increase in the risk of adverse health outcomes in affected fetuses.28 The fact that eight fetuses experienced Cd exposures above the established IVRfD benchmark underscores the critical need for reevaluating safety thresholds and monitoring practices in transfusions for this population. Additionally, our findings suggest a transfer of Cd between maternal and fetal circulations, corroborated by the correlations observed between RBC transfusions and cord and maternal blood. The detectable presence of Cd in maternal and cord blood supports Cd’s ability to cross the placental barrier; however, the significantly higher maternal Cd concentration suggests that the placenta acts as a partial barrier.34,40 This aligns with research demonstrating reduced Cd levels in cord blood, although the present study confirms that median Cd levels in cord and maternal venous blood were significantly lower than the 0.704 and 0.983 µg/L reported in Saudi Arabia.34 Despite these generally lower levels, elevated Cd levels (>1 µg/L) were observed in 11 maternal venous and three cord blood samples. This elevation is likely to be related to tobacco exposure,23 including one case of maternal smoking and 14 cases of exposure to second-hand smoke. Our data indicate that RBC transfusions could expose fetuses to Cd during a critical developmental period. Moreover, given Cd’s long half-life (10–30 years) and its tendency to accumulate in tissues, a heightened potential exists for long-term health risks, including cancer.41

While we found no transfusion bags that surpassed the CDC’s action level for Pb exposure in children,24 several bags exceeded less stringent thresholds.25,26 Specifically, four bags contained lead levels higher than a cutoff value proposed by the CDC’s subcommittee on Pb poisoning prevention; additionally, a significant number exceeded the interim reference level designated for evaluating potential adverse effects of dietary Pb in children and women of childbearing age.26 In our analysis, we observed that fetuses that received RBC transfusions between 18 and almost 35 weeks of gestation were exposed to Pb levels that exceeded the safety threshold of 0.19 µg/kg body weight in a significant number of cases.15 Specifically, 117 transfusions delivered Pb doses above this critical level. Furthermore, a subset of 10 fetuses experienced exposure from 5–9 transfusion bags, each of which contained elevated Pb levels. This exposure pattern underscores the urgent need to address and mitigate Pb risks in medical interventions, particularly during the critical stages of fetal development. Given Pb’s neurotoxicity and classification as probably carcinogenic in humans,13 the German Federal Agency’s Commission suspended the reference level for blood Pb,9 suggesting that an IVRfD of 0.19 µg Pb/kg body weight cannot be considered acceptable. Moreover, the median Pb concentration in cord blood was not significantly different from that in maternal venous blood, consistent with findings from our previous study that reported lower Pb levels in both blood types.34 In the current study, of the 21 cord and 30 maternal blood samples analyzed, 6 and 9 samples exceeded the 50 µg/L Pb threshold, respectively.24 Although we found no direct correlation between Pb levels in transfusion bags and those in blood samples, one cannot ignore the potential for RBC transfusions to contribute to Pb exposure. This concern is heightened by the high environmental Pb levels to which the Saudi population is exposed from typical as well as unusual sources,42,43,44 which have been further amplified following recent increases in industrialization and urbanization.45 Given the significant risks associated with cumulative Pb exposure, particularly to the developing brains and organs of vulnerable populations, this is an area of serious concern.46

In this study, the median As concentration in RBC transfusion bags was found to be notably lower than concentrations previously reported in transfusions given to preterm neonates.9 Despite this, our findings contrast with those of other research that detected no arsenic in blood transfusions,23 indicating that As contamination can vary significantly between different clinical settings. Crucially, several transfusion bags exceeded the recognized safety thresholds for children and adults,27 highlighting a sporadic but significant risk of higher As exposure through transfusions. Although RBC transfusions are not typically a significant source of As exposure, the observed positive correlation between As levels in RBC transfusions and cord blood is noteworthy. As such a correlation was absent between maternal venous blood and RBC transfusions and cord blood, there is a need to further investigate the mechanisms of As transfer and its accumulation in the fetus compared with the mother. Additionally, elevated As levels above the RV95 threshold for children.27 were detected in three cord and seven maternal blood samples. However, caution is required when interpreting these results, as our measurements were of total As rather than its more toxic inorganic forms or urinary methylated metabolites, which could differ significantly in terms of health implications.47

When examining the impact of multiple IUBTs and fetal gestational age at transfusion on metal levels in cord and maternal blood, we observed that fetuses receiving more frequent transfusions may experience higher exposure to Cd, a potentially harmful metal. This finding suggests a need for further investigation into sources and potential health effects of Cd exposure during multiple blood transfusions in fetuses. The lack of significant associations for other metals in cord blood may be due to a range of other factors not considered in this analysis, such as differences in the efficiency of placental transfer of metals, genetic variability among mothers and fetuses that might influence metal metabolism, accumulation dynamics, and the limited sample size of the study. Further research is necessary to explore these potential influences to better understand the dynamics of metal exposure during pregnancy.

Our study revealed that 17 fetuses showed HI > 1, with Pb being the major contributor, followed by Hg and Cd. This indicates that exposure to a combination of these toxic metals through RBC transfusions at such a vulnerable age is concerning, suggesting an increased potential for overall non-cancer adverse health effects. Such effects include those on neurodevelopment, obesity, congenital anomalies, and cardiometabolic diseases, which might be reflected in children’s early or later stages of life.9,48,49,50

Our study has some limitations that warrant attention. (1) The small sample size may have constrained our ability to identify correlations among certain metals. (2) There is a lack of essential data related to RBC transfusions. (3) The estimated fetal weight was not consistently measured or recorded in patient charts. (4) Not all RBC transfusions were analyzed for metal content due to oversight by nursing staff in keeping the remaining residual. (5) Cord blood samples were not obtained for all participants in the delivery room. (6) Pre-transfusion heavy metal levels in the mothers were not measured, which may have contributed to the heavy metal levels observed in the cord blood samples. (6) The HI did not consider the combined effects of the metals as a mixture. Consequently, the potential health hazard may be underestimated if the interactions between the metals are synergistic or overestimated if these interactions are antagonistic.51

In conclusion, our study’s findings significantly enhance the understanding of fetal exposure to toxic metals during IUBT procedures. They also contribute valuable insights to the limited research that exists in this field. Furthermore, this study’s findings demonstrate that Hg, Cd, Pb, and As levels often exceed established safety thresholds, which highlights not only the efficient transfer of these metals through the placental barrier but also the risks of cumulative exposure associated with multiple transfusions. While IUBTs are essential for treating fetal anemia, they may have significant health consequences later in life, particularly with regard to neurodevelopment. These findings underscore the urgent need to reevaluate blood donor screening protocols and develop revised clinical guidelines to reduce fetal metal exposure and enhance fetal health. Additionally, long-term monitoring must be initiated for children who have undergone an IUBT.

Data availability

Data are available upon request.

References

Dean, L. Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens [Internet]. Ch. 4, Hemolytic disease of the newborn (National Center for Biotechnology Information US, 2005).

Lindenburg, I. T., van Kamp, I. L. & Oepkes, D. Intrauterine blood transfusion: current indications and associated risks. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 36, 263–271 (2014).

World Health Organization (WHO). Screening Donated Blood for Transfusion-transmissible Infections (WHO, 2010).

Aly, S. M. et al. Lead, mercury, and cadmium concentrations in blood products transfused to neonates: elimination not just mitigation. Toxics 11, 712 (2023).

Aly, S. M., Omran, A., Abdalla, M. O., Gaulier, J. M. & El-Metwally, D. Lead: a hidden “untested” risk in neonatal blood transfusion. Pediatr. Res. 85, 50–54 (2019).

Averina, M. et al. Environmental pollutants in blood donors: the multicentre Norwegian donor study. Transfus. Med. 30, 201–209 (2020).

Godbey, E. A. & Thibodeaux, S. R. Ensuring safety of the blood supply in the United States: donor screening, testing, emerging pathogens, and pathogen inactivation. Semin. Hematol. 56, 229–235 (2019).

White, K. M. R. et al. Donor blood remains a source of heavy metal exposure. Pediatr. Res. 85, 4–5 (2019).

Al-Saleh, I. et al. Exposure of preterm neonates to toxic metals during their stay in the neonatal intensive care unit and its impact on neurodevelopment at 2 months of age. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 78, 127173 (2023).

Gehrie, E. et al. Primary prevention of pediatric lead exposure requires new approaches to transfusion screening. J. Pediatr. 163, 855–859 (2013).

Schulz, C., Angerer, J., Ewers, U. & Kolossa-Gehring, M. The German Human Biomonitoring Commission. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 210, 373–382 (2007).

Schulz, C., Wilhelm, M., Heudorf, U. & Kolossa-Gehring, M. Reprint of “Update of the reference and HBM values derived by the German Human Biomonitoring Commission. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 215, 150–158 (2012).

Wilhelm, M., Heinzow, B., Angerer, J. & Schulz, C. Reassessment of critical lead effects by the German Human Biomonitoring Commission results in suspension of the human biomonitoring values (HBM I and HBm II) for lead in blood of children and adults. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 213, 265–269 (2010).

Rocha, A. & Trujillo, K. A. Neurotoxicity of low-level lead exposure: history, mechanisms of action, and behavioral effects in humans and preclinical models. Neurotoxicology 73, 58–80 (2019).

Falck, A. J., Sundararajan, S., Al-Mudares, F., Contag, S. A. & Bearer, C. F. Fetal exposure to mercury and lead from intrauterine blood transfusions. Pediatr. Res. 86, 510–514 (2019).

Barnes, D. G. & Dourson, M. Reference dose (RfD): description and use in health risk assessments. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 8, 471–486 (1998).

Takci, S. et al. Lead and mercury levels in preterm infants before and after blood transfusions. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 188, 344–352 (2019).

United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). EPA’s National-scale Air Toxics Assessment, an Overview of Methods for EPA’s National-scale Air Toxics Assessment (US EPA, 2011).

Kiserud, T. et al. The World Health Organization fetal growth charts: a multinational longitudinal study of ultrasound biometric measurements and estimated fetal weight. PLoS Med. 14, e1002220 (2017).

United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). Mercury: Human Exposure (US EPA, 2007).

Mahaffey, K. R. Mercury exposure: medical and public health issues. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 116, 127–153 (2005).

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Cadmium. OSHA 3136-06R (U.S. Department of Labor, 2004).

Boehm, R. et al. Toxic elements in packed red blood cells from smoker donors: a risk for paediatric transfusion? Vox Sang. 114, 808–815 (2019).

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Low Level Lead Exposure Harms Children: A Renewed Call for Primary Prevention. Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention (CDC, 2012).

Paulson, J. A. & Brown, M. J. The CDC blood lead reference value for children: time for a change. Environ. Health 18, 16 (2019).

Flannery, B. M. et al. U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s interim reference levels for dietary lead exposure in children and women of childbearing age. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 110, 104516 (2020).

Saravanabhavan, G. et al. Human biomonitoring reference values for metals and trace elements in blood and urine derived from the Canadian Health Measures Survey 2007–2013. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 220, 189–200 (2017).

Falck, A. J., Medina, A. E., Cummins-Oman, J., El-Metwally, D. & Bearer, C. F. Mercury, lead, and cadmium exposure via red blood cell transfusions in preterm infants. Pediatr. Res. 87, 677–682 (2020).

Rossman, T. G. Arsenic in Environmental and Occupational Medicine (eds Rom, W. N. & Markowitz, S. B.) 1006–1021 (Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2007).

Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS). Chemical Assessment Summary: Arsenic, Inorganic; CASRN 7440-38-2 (US EPA, 1991).

Sakamoto, M. et al. Plasma and red blood cells distribution of total mercury, inorganic mercury, and selenium in maternal and cord blood from a group of Japanese women. Environ. Res. 196, 110896 (2021).

WHO & and International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS). Methylmercury (WHO, 1990).

Hong, Y. S., Kim, Y. M. & Lee, K. E. Methylmercury exposure and health effects. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 4, 353–363 (2012).

Al-Saleh, I., Shinwari, N., Mashhour, A., Mohamed Gel, D. & Rabah, A. Heavy metals (lead, cadmium and mercury) in maternal, cord blood and placenta of healthy women. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 214, 79–101 (2011).

Jedrychowski, W. et al. Fish consumption in pregnancy, cord blood mercury level and cognitive and psychomotor development of infants followed over the first three years of life: Krakow epidemiologic study. Environ. Int. 33, 1057–1062 (2007).

Lederman, S. A. et al. Relation between cord blood mercury levels and early child development in a World Trade Center cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 116, 1085–1091 (2008).

Sato, R. L., Li, G. G. & Shaha, S. Antepartum seafood consumption and mercury levels in newborn cord blood. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 194, 1683–1688 (2006).

Stern, A. H. & Smith, A. E. An assessment of the cord blood:maternal blood methylmercury ratio: implications for risk assessment. Environ. Health Perspect. 111, 1465–1470 (2003).

Park, J. D. & Zheng, W. Human exposure and health effects of inorganic and elemental mercury. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 45, 344–352 (2012).

García-Esquinas, E. et al. Lead, mercury and cadmium in umbilical cord blood and its association with parental epidemiological variables and birth factors. BMC Public Health 13, 841 (2013).

Wang, M. et al. A review on cadmium exposure in the population and intervention strategies against cadmium toxicity. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 106, 65–74 (2021).

Al-Saleh, I. Sources of lead in Saudi Arabia: a review. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 17, 17–35 (1998).

Al-Saleh, I. Reference values for heavy metals in the urine and blood of Saudi women derived from two human biomonitoring studies. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 225, 113473 (2020).

Al-Saleh, I., Al-Enazi, S. & Shinwari, N. Assessment of lead in cosmetic products. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 54, 105–113 (2009).

Shaik, A. P., Sultana, S. A. & Alsaeed, A. H. Lead exposure: a summary of global studies and the need for new studies from Saudi Arabia. Dis. Markers 2014, 415160 (2014).

Dórea, J. G. Environmental exposure to low-level lead (Pb) co-occurring with other neurotoxicants in early life and neurodevelopment of children. Environ. Res. 177, 108641 (2019).

Ashley-Martin, J., Fisher, M., Belanger, P., Cirtiu, C. M. & Arbuckle, T. E. Biomonitoring of inorganic arsenic species in pregnancy. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 33, 921–932 (2023).

Huang, W. et al. In-utero co-exposure to toxic metals and micronutrients on childhood risk of overweight or obesity: new insight on micronutrients counteracting toxic metals. Int. J. Obes. 46, 1435–1445 (2022).

Takeuchi, M., Yoshida, S., Kawakami, C., Kawakami, K. & Ito, S. Association of maternal heavy metal exposure during pregnancy with isolated cleft lip and palate in offspring: Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS) cohort study. PLoS ONE 17, e0265648 (2022).

Zhang, M. et al. A metabolome-wide association study of in utero metal and trace element exposures with cord blood metabolome profile: findings from the Boston Birth Cohort. Environ. Int. 158, 106976 (2022).

Wilbur, S. B., Hansen, H., Pohl, H., Colman, J. & McClure, P. Using the ATSDR guidance manual for the assessment of joint toxic action of chemical mixtures. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 18, 223–230 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The investigators gratefully acknowledge the Fetal Therapy Unit (Samar Bagabas and Wejdan Almadkaly), Labor and Delivery Unit (Tonya King and Lily Fung), and Blood Bank (Mohammed Alsalmi), and the pregnant women for their participation in this study.

Funding

The work was funded by the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre as part of the Environmental Health Program Research activities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.A.: Conceptualization/Writing/Review and editing/Formal analysis/Visualization/Project administration/Supervision; H.A.: Recruiting patients’/sample analysis; R.A.: Analysis; H.A.: Resources include funding, and M.T.: Resources. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the KFSH&RC (approval number RAC #2200007). Informed consent was obtained from the mothers at enrollment.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplemental information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Saleh, I., Alnuwaysir, H., Al-Rouqi, R. et al. Fetal exposure to toxic metals (mercury, cadmium, lead, and arsenic) via intrauterine blood transfusions. Pediatr Res 97, 647–654 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03504-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03504-w