Abstract

Complexity science is a discipline which explores how complex systems behave and how we interact with them. Though it is widely implemented outside medicine, particularly in the sciences involving human behavior, but also in the natural sciences such as physics and biology, there are only a few applications within medical research. We propose that complexity science can provide new and helpful perspectives on complex pediatric medical problems. It can help us better understand complex systems and develop ways to cope with their inherent unpredictabilities. In this article, we provide a brief introduction of complexity science, explore why many medical problems can be considered ‘complex’, and discuss how we can apply this perspective to pediatric research.

Impact

-

Current methods in pediatric research often focus on single mechanisms or interventions instead of systems, and tend to simplify complexity. This may not be appropriate.

-

Complexity science provides a framework and a toolbox to better address complex problems.

-

This review provides a starting point for the application of complexity science in pediatric research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Complexity is a word we often use in common language to describe something that is difficult to understand. In complexity science, we make a distinction between complicated and complex systems. Complicated systems may have many parts that interact in intricate ways, but the system can be pulled apart, its components analyzed, the system understood and its future behavior predicted. An example is a car, where despite it being a complicated machine, we can predict what will happen when we change a part. In contrast, complex systems have certain characteristics, which we will discuss later, which make the whole more than the sum of its parts, and which make them to a certain extent unpredictable.1,2,3 Think for example of hurricane trajectory predictions, which, despite enormous amounts of data and on the clock analyses, are almost never 100% accurate. What characterizes hurricanes and makes them so difficult to predict? To what extent are health outcomes of children also unpredictable? And most importantly, how can we best deal with this unpredictability when doing research or when taking treatment decisions in clinical practice?4 (Box 1).

In this article, we will discuss the characteristics of complex systems and use clinical examples to show how many problems in pediatrics can be considered complex. Moreover, we will discuss how complexity science deals with this complexity and the resulting unpredictability, both in terms of research, as well as in terms of clinical management. Our thinking on how to apply the complexity perspective in pediatrics is still in its infancy. In this article, we intend to start the discussion on complexity in pediatrics, with the longer-term aim to develop research projects based on complexity science.

What is complexity science?

Origins of complexity science

Complexity science originates from cross-disciplinary collaborations starting in the 1980s between computer scientists, physicists, chemists and biologists.5 These scientists realized that the systems they were looking at in their own fields, had striking similarities with systems in apparently unrelated fields. These systems varied from chemical reactions to biological processes to political systems and economies. They realized that these systems had similar characteristics and contained a certain level of inherent unpredictability and started to model this using sophisticated mathematical modeling strategies. Most of all, they realized the value of true interdisciplinary research to create a better understanding of complex systems. Over the years, many of the characteristics of complex systems have been defined, and complexity science has been applied in many fields, including physics, chemistry, biology, but also management and social sciences, and many research institutes on complex systems have been established worldwide.

Characteristics of complex systems

In Table 1, we describe some of the key characteristics of complex systems.3,5 The first four characteristics are considered to be the essential conditions for complexity to arise and in complex systems, these conditions will give rise to some or all of the remaining six characteristics or products. For a system to qualify as a complex system, the initial four conditions plus the products self-organization and robustness must be present. The other characteristics are often present but are not critical.

Self-organization or emergence requires further explanation. Emergence means that there is spontaneous order and organization as a result of many interactions between multiple parts. Not only does the system respond to its environment, but it is able to change its internal structure in response to it. For example, economies change their structure in response to money supply, growth rate, political stability, etc. The human brain changes its structure in response to things we do repeatedly – ‘neurons that fire together, wire together’. The architecture of a tumor varies depending on the supply of nutrients and oxygen and its interaction with immune cells, etc.6 Key requirement for emergence is that there is no a priori design, and no central control, emergence happens solely via interaction of the system with its environment through interactions among its parts.3

Recognizing complex systems

There is little debate in the field of biology on the fact that (human) cells, organs and the (human) body are complex systems.7,8 Social, environmental, economic and many other systems are considered complex as well and there have been strong pleas for the use of a complexity approach in public health.9,10 In clinical medical research, we deal with many of these complex systems simultaneously, because we are interested in how a diagnosis or a treatment affects the (long term) health outcomes of children.11,12,13,14

How can we know whether something is a complex system? There is no such thing as a complexity-test. A system with many interacting parts that defies our abilities to understand or predict it, and that meets the criteria described in the table, should makes us wonder whether we should be studying such a system through the lenses and methods of complexity science. If there are no observable patterns at all (chaos), prediction is impossible and a complexity approach may not help. The questions we ask also matter. If we want to predict whether summers are warmer than winters, we may not need to consider complexity. If we want to predict the exact temperature on June 19, 2025, we do.

It is important to realize that we can look at complexity at many different levels. For example, we can look at a complex health issue within a cell, an organ, a human body, an intensive care unit, a hospital system, a national healthcare system, or on a global scale. Each of these are systems within systems, and each consist of many components and can qualify as a complex system, but they require different approaches and considerations. The level at which one approaches a system will depend on the questions one is trying to answer. In this paper, we focus on human health and clinical medical research, which involves several levels of complexity. We will pragmatically refer to biological complexity (everything that happens inside the human body, including the effects of interventions), within hospital complexity (everything that happens in the healthcare system setting, including interactions between parents, hospital staff, and collaborations with other centers) and out of hospital complexity (everything that happens between people inside and outside of the hospital, e.g., their social network, and everything that happens after patients are discharged, e.g., education) (Box 2).

We can also look at complexity over different timescales. This is important because the structure of a complex system can be more stable (e.g., a human cell) or less stable (e.g., an economy). We need to keep this in mind when we research complex systems. There is a time window within which we can expect stability, and therefore we can make good predictions of the system. But beyond that time window, predictions become very difficult. Different disciplines often look at different timescales with different methods.

Understanding complex systems

Complex systems, because of characteristics such as self-organization, non-linearity and adaptive behavior, are unpredictable, in the sense that we can never know with 100% certainty how the system will behave or what the effect of an intervention will be. This unpredictability is crucial for the system, as it reflects its adaptability, robustness, and self-organizing capability (Box 3).

In a sense, many systems can be considered complex, and they are all connected to other complex systems. Does that mean that everything is always unpredictable and we should give up on research? On the contrary. Complexity does not mean that everything is happening randomly and we cannot know anything. As described before, complex systems are unpredictable to some extent, but they can form patterns which we can analyze to better understand their behavior. This is where complexity science provides us with tools to identify these patterns and improve our understanding of complex systems. The key is to remember that because the patterns are formed by a complex system, any internal change or external intervention may cause that complex system to adapt or shift in ways we cannot always foresee, especially when we look at long term outcomes (Box 4). One important implication of complexity science is that it is unlikely that there is a single disease pathway or mechanism that we can intervene on to ‘shift’ the system completely, because that would make a system highly vulnerable. There are often collateral pathways, there is redundancy, and the system’s ability to adapt. Although there have been examples of successful single golden bullet treatments, such as vitamin C for scurvey, or surfactant for respiratory distress syndrome, these are most likely exceptions to the rule. A second implication is that when we intervene in a system, the system responds, and then we respond, so action and reaction are ‘entangled’, and co-evolve.

Don’t we just need more data?

The most common argument against complexity science is that the unpredictability of complex systems results from a lack of knowledge. ‘We just don’t have enough data, but once we have more data, we will understand the system and eliminate unpredictability.’ Complexity science states that although lack of data is clearly a problem in medicine, because of the way complex systems function, some degree of unpredictability will always remain. So why exactly won’t collecting more data solve the problem of unpredictability in complex systems? We identify three main arguments.

-

1.

The reference class problem. In clinical research, when everything is measured, every human being is unique and therefore different. To make accurate predictions, we would need to include reference groups in our studies for each of the relevant characteristics that can differ between people, and all the interactions and feedback loops. Evidently, there are too many variables and not enough data (and humans) in the world to solve this. This will mean that patients will always differ in some ways from patients in clinical studies, and therefore predictions will sometimes fail and treatments that are expected to benefit patients may not.15,16

-

2.

Changes over time. Humans and their environment change constantly. The moment we finish a study, the world has already moved on and our predictions or understandings – even if they were impeccable at the time the data were generated - may be out of date. In addition, intervening in a system will often change the system. We are always a step behind; data cannot predict the future.

-

3.

Interconnecting systems. Complex systems are often part of other systems and consist of subsystems. Most of the time, we cannot investigate all relevant systems that are connected to our system of interest. We need to put boundaries and because complex systems are open systems, change can always occur across these boundaries.

Some may argue that artificial intelligence will allow us to reduce unpredictability. Though we expect that artificial intelligence can improve our understanding of complex systems substantially, because it can account for the many interactions and feedback loops that conventional analytic methods cannot, we maintain our claim that there will still be irreducible uncertainty, for the same reasons as mentioned above.

How can complexity science help us improve pediatric research?

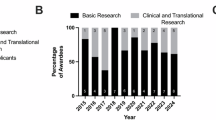

Over the past years, complexity science has gained some traction in medical research, although, the focus has mostly been on health care organization, epidemiology and public health and not on applied clinical medical research.9,10,11,12,14,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 For various medical topics, there have been papers and books describing the need for a complexity approach, for example in sepsis, burn care, asthma, and related to the Covid pandemic.11,17,24,25,26,27 Several systematic reviews, which looked at applications of complexity science in health care, identified only 15–20 papers per year, of which only a minority of papers were about clinical research, and only a handful in pediatrics. Most importantly, these reviews highlight that although the concepts of complexity science are being embraced more and more, definitions vary, and practical applications are lacking. Some important advocates of complexity science within health care have highlighted this as well.14,18,28,29,30,31,32,33 In short, complexity science has not been explored sufficiently in pediatric research.

We have identified several ways in which complexity science could improve pediatric research, which we will describe below, with accompanying examples. (Fig. 1) It is tempting to think that complexity science will provide us with ultimate solutions and magic bullets. However, if complex systems are truly as complex as we think they are, this is unlikely to happen. Instead, complexity science can provide us with better questions and a richer toolbox to start answering those.

Complexity science is a tool to help us identify aspects of complex systems that we should address in research

In order to better understand a complex system, we need to look at it from as many angles as possible. Complexity science helps us be aware of the different characteristics of complex systems (e.g., self-organization, adaptation, feedback loops etc)10,34,35 (Box 5).

In addition, within complexity science, different methods for mapping or visualizing complex systems have been developed, which can help researchers get a better overview of many of the factors at play (Box 6, Fig. 2).

Reprinted from “How exposure to chronic stress contributes to the development of type 2 diabetes: A complexity science approach,” by N. Merabet, 2022, Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology volume 65, 100972. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons CC-BY license, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Different aspects of complex systems will need different research approaches (measures of complexity)

The different characteristics of complex systems, such as non-linearity, emergence, and feedback, cannot be measured using just one method but require a combination of so called ‘measures of complexity.’ Many measures of complexity have been introduced and the list is still growing. They vary from simple analyses such as counts and variance for numerosity and diversity to methods that require more sophisticated computational modeling, such as Shannon entropy, agent based modeling or power laws5 (Box 7, Fig. 3). Stronks et al. describe that within epidemiological research, we need to look at patterns in place, time, and on a person-level, interactions, non-linearity, feedback loops, adaptation over time, and many other aspects, each of which require different types of data and different analyses.35 For medical research, we have the additional challenging task to connect these data with biological complex systems data.

Critical slowing down is a generic indicator that the patient has lost resilience in the sense that the patient may shift more easily from his current “healthy” state into an alternative “diseased” state. The patient (represented by the ball in the stability landscape in (a) and (b) can be in a diseased state (e.g., in a major generalized depression) and in a more healthy state (e.g., in a healthy mood state). Far from the tipping point, the patient is highly resilient, and perturbations will not easily flip the subject out of the basin of attraction to the alternative diseased state (a). Changes in conditions (e.g., drug application, stress, and comorbidity) can lower resilience and shrink the basin of attraction (b), so that a perturbation can more easily flip the patient into the severe disease state. As the basin of attraction becomes smaller, its slopes become less steep, implying that the return rate to equilibrium upon small perturbations slows down. Recovery time after a small perturbation is higher (E vs C) if the patient is closer to the tipping point. The effect of this slowing down can also be measured as (F vs D) increased variance in randomly induced fluctuations in the current state of the patient, caused by small external stressors, and (H vs G) in increased “memory” or increased (lag-1) autocorrelation between the serial measurements when the disease state is moving toward its tipping point. Reprinted from “Slowing Down of Recovery as Generic Risk Marker for Acute Severity Transitions in Chronic Diseases,” by M.G.M. Olde-Rikkert, 2016, Critical Care Medicine, Mar;44(3):601-6. Copyright © 2016 by the Society of Critical Care Medicine and Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Computational, mathematical strategies can help to improve the way we describe and visualize complex systems, because they can incorporate many components and interactions.36 It goes beyond the scope of this article to describe them in detail, but we refer to reviews published elsewhere.5 Rod et al. provide a thorough overview of epidemiologic strategies, which includes items like life course models, network analysis, computer simulation models such as system dynamics models and agent-based models, functional data analyses, flexible AI based methods, etc10 (Box 8). Even though these methods may often feel like a black box, and come with their own challenges and limitations, we may need to accept that difficult questions about complex systems may require difficult methods. The alternative, trying to answer difficult questions about complex systems using only simple methods, will almost invariably lead to research waste and may potentially be harmful.

Importantly, complexity science challenges the status of randomized clinical trials as the single gold standard for medical treatment effects. Although there is a clear rationale for randomized controlled trials, and they are a valuable research tool, we should not forget that they only answer very narrowly defined research questions and attempt to isolate the effect of a single causal factor without looking at context and the system as a whole.

Aside from the known limitations of RCTs, complexity science adds the understanding that any treatment effect is in a sense a dynamic, emergent effect.37,38 If an RCT shows beneficial effect of treatment A, this effect may have occurred via different ‘routes’ within a complex system, such as interactions with patient characteristics or co-treatment, but also social factors such as decision making strategies or power dynamics, which may all change over time and vary between hospitals, patients and caregivers. In other words, the effect of an intervention depends on its context, though of course this dependency will vary depending on the type of intervention studied. The fundamental generalizability assumption of Evidence-Based Medicine is that as long as we copy the intervention in the same clinical population (following the RCT inclusion and exclusion criteria), we can expect a similar treatment effect (on a group level) in other hospitals. The underlying assumption is that context will be relatively similar or will have little impact on the effect. However, RCTs often do not provide us with sufficient information to ascertain whether the complex system in our hospital resembles the complex system in the RCT enough to warrant implementation of the intervention. The need for thorough considerations and lack of consensus on how to assess generalizability of RCTs has also been highlighted in epidemiologic literature.39 Therefore, though RCTs can be helpful in identifying potential treatment effects, complexity science claims that RCTs alone provide insufficient information to guide implementation in clinical care, and need to be complemented with other types of research as well as clinical judgement. Evidence-based medicine traditionally teaches an evidence pyramid, with systematic reviews and then randomized trials set at the top by default. Complexity science, on the contrary, sees different methods as complementary and interdependent, each answering related research questions, which are all needed to come to a fuller understanding of a system.40

Complexity science also places a strong emphasis on the human factor and social sciences research. People often don’t act the way we expect them to act. Patients, caregivers, nurses, and clinicians may have motivations, biases and unconscious convictions that impact the way they make decisions or deliver care. All these factors are part of the same complex system in which we implement medical interventions. An example from neonatology was a neonatologist who transfused a child at the high threshold during the Planet-2/MATISSE RCT in an infant randomized to the low threshold, because she had followed the protocol for the low threshold on the previous day and that child passed away due to bleeding. Thus, the personal experience of health workers is filtered through knowledge and belief systems to influence adherence to protocols and guidelines. Despite knowing that the bleeding was unlikely to be caused by withholding the transfusion, she could not make herself withhold another transfusion in a similar scenario. The psychological side of decision making, how healthcare workers cope with uncertainty, and many other factors are important and need to be taken into account when we consider diagnostic tools or treatments.41 This is also why qualitative research is important and highly relevant. Not everything can be captured in numbers. Qualitative research needs to be reinstated as a valid scientific method in medicine42 (Box 9).

Complex systems require other types of interventions and strategies to manage them than complicated systems

We suspect that many clinicians may recognize the inherent unpredictability of the complex systems they are dealing with, but they may have come to accept that the only way to do research and to develop guidelines is by ignoring some of the complexity and simplifying the system. In fact, one could say that there is a mismatch: we perform research as if the systems we look at were complicated, even though in fact they are complex. Complexity science proposes another, more pragmatic approach, where we anticipate unpredictability, and develop treatment plans and a health care system that can cope with unexpected changes and can quickly adapt and improve.18,43 We can imagine that guidelines developed through the application of complexity science will be different, and will include strategies that allow for more flexibility in patient management.12,13 Of course this is a delicate balance because the stakes are high, and junior doctors especially need guidance to support their practice. This is a widespread difficulty across clinical practices, and needs further investigation in an interdisciplinary way.13 In this context, we propose that we can learn a lot from other equally complex disciplines and fields where complexity science is being applied (Box 10).

Complexity science is a tool to help us identify leverage points in complex systems

Leverage points are points in a complex system where a relatively small change could lead to a ‘shift’ or large change in the system’s behavior. Therefore, they are potential targets for interventions. Often, multiple interventions and leverage points need to be addressed to obtain change.44,45 Nobles et al. developed the Action Scales Model, a conceptual tool to identify key points for action within complex adaptive systems. They divided leverage points into events, structures, goals and beliefs. Intervening at the goals or beliefs level (e.g., changing people’s perception of unhealthy food) is often more effective than intervening at structural or event level (e.g., removing a snack bar from a neighborhood).45 In the medical context, addressing beliefs of clinicians regarding the effectivity of a certain treatment may be more effective than implementing a guideline requiring them to change their behavior. To our knowledge, little has been published on leverage points in relation to biological complexity. But we can imagine this approach will help identify new biological leverage points or a combination of leverage points which can be targeted (Box 11).

Complexity science can help us identify and avoid research waste and better prioritize research

A system is not either complex or not complex, but shows variation in the degree of complexity, and our understanding of the system varies too. Sometimes we can identify patterns that can help us guide practice, and we improve our understanding of the system. Complexity science can help us distinguish between questions and methods that have the potential to contribute to this understanding, and those that don’t. For example, looking at a single intervention and a single outcome in an explicitly complex system will most likely not add to our understanding of that system, or help us in decision making, and could therefore be considered research waste. Complexity science helps us to assess the extent to which we need to take complexity into account, and make intentional and explicit decisions about this. If the patterns are quite clear, and stable, we have a lot of understanding of the system, and if not many other systems are involved, it may be entirely justifiable to use conventional methods to explore these patterns. But if such assumptions don’t hold, using conventional methods (even if applied correctly and with high quality data) will often lead to research waste (Box 12).

It is not a single study, but a combination of studies exploring complexity around a single theme to create a ‘thick causal story’, that we consider a hallmark for complexity inspired clinical research. We acknowledge that, particularly in pediatrics, there is a need for more research funding, support and resources, and this will impact the extent to which researchers and research groups are able to explore many aspects of a complex problem. But on the other hand, if complexity science helps us to focus our limited resources on the research questions that matter and can be answered, this may ultimately be a more efficient strategy.

Conclusions

In short, complexity science provides a perspective that can be helpful when we research inherently complex and unpredictable systems, such as those we encounter in pediatrics. It can help us lessen the gap between evidence and practice by on the one hand improving our understanding of complex systems, and on the other hand by acknowledging the inherent unpredictability of complex systems and developing means to anticipate, adapt, learn and respond (Fig. 1).

It can give guidance in terms of asking better questions, choosing more appropriate and diverse methods, and drawing careful conclusions that our data can support. What is mostly required is so-called ‘negative capacity’, or the ‘ability to resist the urge to conclude’.46 There is discomfort in uncertainty. Complexity science asks us to resist that, to stay in uncomfortable uncertainty, to learn from it, and to expect the unexpected.4,47,48 It requires slow science, persistence, and curiosity. It encourages us to take time to answer the questions that really matter. And it underlines the need to stay humble about what we think we know.

We hope that this article will increase awareness of complexity and provides a starting point for clinical researchers in pediatrics to explore this perspective in their own research and their clinical practice.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Ladyman, J., Lambert, J. & Wiesner, K. What is a complex system? Eur. J. Philos. Sci. 3, 33–67 (2012).

Byrne, D. Complexity Theory and the Social Sciences: An Introduction (Routledge, 1998).

Cilliers, P. Complexity and Postmodernism (Routledge, 1998).

Simpkin, A. & Schwartzstein, R. Tolerating uncertainty, the next medical revolution. NEJM 275, 1713–1715 (2015).

Ladyman, J. & Wiesner, K. What is a Complex System? (Yale University Press, 2020).

Sigston, E. A. W. & Williams, B. R. G. An emergence framework of carcinogenesis. Front. Oncol. 7, 198 (2017).

Ma’ayan, A. Complex systems biology. J. R. Soc. Interface 14, 20170391 (2017).

Cohen, A. A., Ferrucci, L., Fülöp, T., Gravel, D. & Hao, N. et al. A complex systems approach to aging biology. Nat. Aging 2, 580–591 (2022).

Rutter, H., Savona, N., Glonti, K., Bibby, J. & Cummins, S. et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet 390, 2602–2604 (2017).

Rod, N. H., Broadbent, A., Rod, M. H., Russo, F. & Arah, O. et al. Complexity in epidemiology and public health. Addressing complex health problems through a mix of epidemiologic methods and data. Epidemiology. 34, 505–514 (2023).

Greenhalgh, T., Fisman, D., Cane, D. J., Oliver, M. & Macintyre, C. R. Adapt or die - how to the pandemic made the shift from Ebm to Emb+ more urgent. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 27, 253–260 (2022).

Plsek, P. & Greenalgh, T. The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ Evid. Based Med 323, 625–628 (2001).

Braithwaite, J., Churruca, K. & Ellis, L. A. Can we fix the uber-complexities of healthcare? J. R. Soc. Med. 110, 392–394 (2017).

Braithwaite, J. et al. Complexity in Healthcare. Aspirations, Approaches, Applications and Accomplishments. A Whitepaper. (Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Marcquarie University, Australia, 2017).

Dekkers, O. M. & Mulder, J. M. When will individuals meet their personalized probabilities? A philosophical note on risk prediction. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 35, 1115–1121 (2020).

Dahabreh, I. J., Hayward, R. & Kent, D. M. Using Group Data to treat individuals: understanding heterogeneous treatment effects in the age of precision medicine and patient-centred evidence. Int. J. Epidemiol. 45, 2184–2193 (2016).

Sturmberg, J. & Martin, C. Handbook of Systems and Complexity in Health (Springer, 2013).

Greenhalgh, T. & Papoutsi, C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med. 16, 95 (2018).

Luna Pinzon, A. et al. The encompass framework: a practical guide for the evaluation of public health programmes in complex adaptive systems. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 19, 33 (2022).

Lane, P. J., Clay-Williams, R., Johnson, A., Garde, V., Barrett-Beck, L. et al. Creating a healthcare variant cynefin framework to improve leadership and urgent decisionmaking in times of crisis. Leadersh. Health Serv. (Bradf Engl.) ahead-of-print, 454–461 (2021).

Kannampallil, T. G., Schauer, G. F., Cohen, T. & Patel, V. L. Considering complexity in healthcare systems. J. Biomed. Inf. 44, 943–947 (2011).

Augustsson, H., Churruca, K. & Braithwaite, J. Mapping the use of soft systems methodology for change management in healthcare: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 9, e026028 (2019).

Merabet, N. et al. How exposure to chronic stress contributes to the development of type 2 diabetes: a complexity science approach. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 65, 100972 (2022).

Schuurman, A. R., Sloot, P. M. A., Wiersinga, W. J. & van der Poll, T. Embracing complexity in sepsis. Crit. Care 27, 102 (2023).

van Zuijlen, P. P. M. et al. The future of burn care from a complexity science perspective. J. Burn Care Res. 43, 1312–1321 (2022).

Anto, J. M. et al. Why has epidemiology not (yet) succeeded in identifying the origin of the asthma epidemic? Int J. Epidemiol. 52, 974–983 (2023).

Aron, D. Complex Systems in Medicine (Springer, 2020).

Carroll, Á., Collins, C., McKenzie, J., Stokes, D. & Darley, A. Application of complexity theory in health and social care research: a scoping review. BMJ Open 13, e069180 (2023).

Reed, J. E., Howe, C., Doyle, C. & Bell, D. Simple rules for evidence translation in complex systems: a qualitative study. BMC Med 16, 92 (2018).

Churruca, K., Pomare, C., Ellis, L. A., Long, J. C. & Braithwaite, J. The influence of complexity: a bibliometric analysis of complexity science in healthcare. BMJ Open 9, e027308 (2019).

Rusoja, E. et al. Thinking about complexity in health: a systematic review of the key systems thinking and complexity ideas in health. J. Eval. Clin. Pr 24, 600–606 (2018).

Brainard, J. & Hunter, P. R. Do complexity-informed health interventions work? A scoping review. Implement Sci 11, 127 (2016).

Sturmberg, J. P., Martin, C. M. & Katerndahl, D. A. Systems and complexity thinking in the general practice literature: an integrative, historical narrative review. Ann. Fam. Med 12, 66–74 (2014).

Russo, F. et al. A Pluralistic (Mosaic) Approach to Causality in Health Complexity. In: The Routledge Handbook of Causality and Causal Methods (Illari P. and Russo F., eds.) (Routledge, 2025 Forthcoming).

Stronks, K., Crielaard, L. & Hulvej Rod, N. Systems Approaches to Health Research and Prevention. In: Handbook of Epidemiology (Ahrens, W. & Pigeot, I. eds.) (Springer, 2024).

Barbrook, J. & Penn, A. Systems Mapping. How to Build and Use Causal Models of Systems (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022).

Deaton, A. & Cartwright, N. Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials. Soc. Sci. Med 210, 2–21 (2018).

Ioannidis, J. P. A. Randomized controlled trials: often flawed, mostly useless, clearly indispensable: a commentary on Deaton and Cartwright. Soc. Sci. Med 210, 53–56 (2018).

Dekkers, O. M., von Elm, E., Algra, A., Romijn, J. A. & Vandenbroucke, J. P. How to assess the external validity of therapeutic trials: a conceptual approach. Int. J. Epidemiol. 39, 89–94 (2010).

Cartwright, N. Rigour versus the need for evidential diversity. Synthese 199, 13095–13119 (2021).

Hillen, M. A., Gutheil, C. M., Strout, T. D., Smets, E. M. A. & Han, P. K. J. Tolerance of uncertainty: conceptual analysis, integrative model, and implications for healthcare. Soc. Sci. Med. 180, 62–75 (2017).

Greenhalgh, T. et al. An open letter to the BMJ editors on qualitative research. BMJ 352, i563 (2016).

Khan, S. et al. Embracing uncertainty, managing complexity: applying complexity thinking principles to transformation efforts in healthcare systems. BMC Health Serv. Res 18, 192 (2018).

Bolton, K. A. et al. The public health 12 framework: interpreting the ‘meadows 12 places to act in a system’ for use in public health. Arch. Public Health 80, 72 (2022).

Nobles, J. D., Radley, D. & Mytton, O. T. & Whole Systems Obesity programme, t. The action scales model: a conceptual tool to identify key points for action within complex adaptive systems. Perspect. Public Health 142, 328–337 (2022).

Blastland, M. The Hidden Half (Atlantic Books, 2019).

Gheihman, G., Johnson, M. & Simpkin, A. L. Twelve tips for thriving in the face of clinical uncertainty. Med. Teach. 42, 493–499 (2019).

Koksma, J. J. & Kremer, J. A. M. Beyond the quality illusion: the learning era. Acad. Med 94, 166–169 (2019).

Schnettler, W. T., Goldberger, A. L., Ralston, S. J. & Costa, M. Complexity analysis of fetal heart rate preceding intrauterine demise. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 203, 286–290 (2016).

Greisen, G. et al. Cerebral oximetry in preterm infants-to use or not to use, that is the question. Front Pediatr 9, 747660 (2021).

Hansen, M. L. et al. Cerebral oximetry monitoring in extremely preterm infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 1501–1511 (2023).

Martini, S. et al. Near-infrared spectroscopy monitoring of neonatal cerebrovascular reactivity: where are we now? Pediatr. Res. 96, 884–895 (2023).

Subramanian, N., Torabi-Parizi, P., Gottschalk, R. A., Germain, R. N. & Dutta, B. Network representations of immune system complexity. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 7, 13–38 (2015).

Walleczek J. Self organized biological dynamics and nonlinear control (Cambridge University Press 2000).

Higgins, J. P. Nonlinear systems in medicine. Yale J. Biol. Med. 75, 247–60 (2002).

Goldberger, A. L. Non linear dynamics for clinicians. chaos theory fractals and complexity at the bedside. The Lancet 347, 1312–14 (1996).

Curley, A. et al. Randomized trial of platelet-transfusion thresholds in neonates. N. Engl. J. Med 380, 242–251 (2019).

Fustolo-Gunnink, S. F. et al. Are thrombocytopenia and platelet transfusions associated with major bleeding in preterm neonates? A systematic review. Blood Rev 36, 1–9 (2019).

Fustolo-Gunnink, S. F. et al. Preterm neonates benefit from low prophylactic platelet transfusion threshold despite varying risk of bleeding or death. Blood. 134, 2354–2360 (2019).

Sola-Visner, M., Leeman, K. T. & Stanworth, S. J. Neonatal platelet transfusions: new evidence and the challenges of translating evidence-based recommendations into clinical practice. J. Thromb. Haemost 20, 556–564 (2022).

Scrivens, A. et al. Survey of transfusion practices in preterm infants in. Europe. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 108, 360–366 (2023).

Patel, R. M. et al. Variation in neonatal transfusion practice. J. Pediatr 235, 92–99.e94 (2021).

Greenberg, R. & Bertsch, B. in Cynefin: Weaving Sense-Making into the Fabric of Our World (Snowden, D. J. ed.) 154–168 (Cognitive Edge Pte Ltd, 2021).

Holt, T. Diabetes Control: Insights from Complexity Science. In: Handbook of Systems and Complexity in Health (Sturmberg, J. P. ed.) (Springer, 2013).

Hundscheid, T. et al. Expectant management or early ibuprofen for patent ductus arteriosus. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 980–990 (2023).

Leykum, L. K. et al. The association between sensemaking during physician team rounds and hospitalized patients’ outcomes. J. Gen. Intern Med. 30, 1821–1827 (2015).

Kenzie, E. S. et al. The dynamics of concussion: mapping pathophysiology, persistence, and recovery with causal-loop diagramming. Front Neurol 9, 203 (2018).

Olde Rikkert, M. G. et al. Slowing down of recovery as generic risk marker for acute severity transitions in chronic diseases. Crit. Care Med. 44, 601–606 (2016).

Captur, G., Karperien, A. L., Hughes, A. D., Francis, D. P. & Moon, J. C. The fractal heart - embracing mathematics in the cardiology clinic. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 14, 56–64 (2017).

Uleman, J. F. et al. Simulating the multicausality of Alzheimer’s disease with system dynamics. Alzheimers Dement 19, 2633–2654 (2023).

Heesters, V. et al. Video recording emergency care and video-reflection to improve patient care; a narrative review and case-study of a neonatal intensive care unit. Front Pediatr 10, 931055 (2022).

Iedema, R. Research paradigm that tackles the complexity of in situ care: video reflexivity. BMJ Qual. Saf. 28, 89–90 (2019).

Buetow, S. Apophenia, unconscious bias and reflexivity in nursing qualitative research. Int J. Nurs. Stud. 89, 8–13 (2019).

Van der Merwe, S. E. et al. Making sense of complexity: using sensemaker as a research tool. Systems 7, 25 (2019).

Cunningham, C., Vosloo, M. & Wallis, L. A. Interprofessional sense-making in the emergency department: a sensemaker study. PLoS One 18, e0282307 (2023).

Simpkin, A. L. et al. Stress from uncertainty and resilience among depressed and burned out residents: a cross-sectional study. Acad. Pediatr. 18, 698–704 (2018).

Eisenhardt, K. & Sull, D. Strategy as simple rules. Harv. Bus. Rev. 79, 106–116 (2001).

Kuijpers, E. Elephant Paths: Paving the Way for a Human-Centered Public Space at Michigan State University. https://popupcity.net/insights/elephant-paths-pavingthe-way-for-a-human-centered-public-space-at-michigan-state-university/ (2023).

Braithwaite, J., Churruca, K., Long, J. C., Ellis, L. A. & Herkes, J. When complexity science meets implementation science: a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med. 16, 63 (2018).

Skivington, K. et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of medical research council guidance. BMJ 374, n2061 (2021).

Chalmers, I. & Glasziou, P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 374, 86–89 (2009).

Ioannidis, J. P. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med. 2, e124 (2005).

Ahn, A. C., Tewari, M., Poon, C. S. & Phillips, R. S. The limits of reductionism in medicine: could systems biology offer an alternative? PLoS Med 3, e208 (2006).

Ahn, A. C., Tewari, M., Poon, C. S. & Phillips, R. S. The clinical applications of a systems approach. PLoS Med. 3, e209 (2006).

Wolpert, M. & Rutter, H. Using Flawed, Uncertain, Proximate and Sparse (Fups) data in the context of complexity: learning from the case of child mental health. BMC Med. 16, 82 (2018).

Berg, M. & Seeber, B. The Slow Professor—Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy (University of Toronto Press, 2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data: S.F.F.G., W.P.B., O.M.D., G.G., E.L. and F.R.; Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: S.F.F.G., W.P.B., O.M.D., G.G., E.L. and F.R.; Final approval of the version to be published: S.F.F.G., W.P.B., O.M.D., G.G., E.L., and F.R.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fustolo-Gunnink, S.F., de Boode, W.P., Dekkers, O.M. et al. If things were simple, word would have gotten around. Can complexity science help us improve pediatric research?. Pediatr Res 98, 442–451 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03677-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03677-4