Abstract

Background

Apnea in newborns causes the glottis to adduct and prevents gas from entering the lungs. As hypoxia is an inhibitor of fetal breathing, we have investigated the effect of hypoxia on glottis patency and breathing in preterm newborn rabbits.

Methods

Rabbit kittens (29 d gestation, term ~32 d; n = 12) were delivered by c-section, fitted with a custom face mask and oesophageal catheter to measure breathing efforts. After birth, kittens underwent phase contrast X-ray imaging while receiving CPAP using the following sequence of gases: (i) room-air, (ii) 100% oxygen, (iii) 100% nitrogen and (iv) 100% oxygen again. Glottis patency was visually assessed to determine %time that the glottis was open in each gas.

Results

The glottis remained open for longer (44.7 ± 1.8% vs. 15.5 ± 1.8%, p < 0.0001) and breathing rates were higher (18.1 ± 0.5 breaths/min vs. 11.3 ± 1.1 breaths/min, p = 0.0001) when kittens were exposed to 100% oxygen compared to room-air. When exposed to 100% nitrogen, breathing became unstable and resulted in apnea and a fully closed glottis in all kittens. Glottis patency and breathing were restored by resuscitating with 100% oxygen.

Conclusion

These results highlight the importance of avoiding hypoxia and promoting stable breathing to ensure the glottis is open when giving CPAP.

Impact

-

While preterm newborns commonly receive non-invasive respiratory support (CPAP) in the delivery room, this can be ineffective, particularly if the infant is apneic.

-

We have demonstrated that hypoxia induces unstable breathing patterns in preterm newborn kittens, eventually causing apnea. When breathing is unstable, the glottis opens but only during inspiration. Between breaths and during apnea, the glottis remains closed, which prevents effective delivery of CPAP via face mask.

-

This study highlights that adequate oxygenation is critically important for maintaining breathing activity and the use of oxygen in the delivery room can enhance the effectiveness of non-invasive respiratory support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The critical role of the upper airway, particularly the glottis, has long been overlooked as an important component of the respiratory system in newborn infants, particularly extremely preterm infants. This is probably because historically most infants requiring respiratory support at birth were intubated,1 which bypasses the glottis. As intubation and mechanical ventilation increase the risk of lung injury, this has prompted a major shift towards a non-invasive approach for all infants, without an appreciation of the important differences.

Non-invasive respiratory support commonly involves continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), provided via a facemask, which requires the infant to spontaneously breathe. Until recently, it was widely assumed that if the infant’s breathing was absent or inadequate, spontaneous breathing can simply be replaced with non-invasively applied intermittent positive pressure ventilation (iPPV). However, the recent demonstration that the glottis can close and prevent air from entering the lung if the infant is not breathing,2,3 has demonstrated both the fallacy of this assumption and the critical role breathing plays in the success of non-invasive respiratory support at birth. It also emphasizes the importance of understanding how respiratory control is regulated in newborns.

In the developing fetus, active glottis adduction during apnea plays a critical role in maintaining lung expansion by restricting liquid efflux from the lung. This causes liquid to accumulate within the future airways, causing the lungs to distend with accumulated liquid, which is the primary stimulus for lung growth in utero.4,5 During development, the fetus makes fetal breathing movements (FBMs), which involve dilation of the glottis in phase with contraction of the diaphragm, with the glottis opening and closing with each breath. However, during sustained or vigorous episodes of FBMs, the glottis remains dilated throughout the respiratory cycle (as it does in adults during quiet breathing), which greatly reduces upper airway resistances. This allows liquid to be lost from the airways, despite the contracting diaphragm, causing a reduction in lung distension.6 Recent studies in newborn rabbits3 and humans2,3 indicate that after lung aeration, glottic function in the newborn is very similar to the fetus. The glottis closes during apnea, only opening briefly during a breath when breathing is intermittent or irregular and remains open when breathing is regular and consistent.2 In any event, when the glottis is closed (adducted) the airways are obstructed, and iPPV is unable to ventilate the lung.2,3

Hypoxia is a potent inhibitor of FBMs in the fetus and newborn7,8 and is relatively common in preterm infants as they often display poor respiratory efforts, unstable breathing patterns and are usually unable to adequately aerate their lungs unassisted.2,3 As such, it is likely that glottic closure in response to a hypoxia-induced apnea prevents the lung from being ventilated when iPPV is applied non-invasively. Thus, despite the best efforts of the caregiver, a spiralling decline of worsening hypoxia, inhibition of breathing and glottic adduction may occur, which only abates when the infant is severely hypoxic and bradycardic. Our aim was to investigate this possibility by determining the relationship between hypoxia, breathing patterns and glottis patency in preterm rabbits immediately after birth. We hypothesised that hypoxia would inhibit breathing and cause the glottis to close whereas reversing the hypoxia and stimulating breathing, using tactile stimulation and high inspired oxygen concentrations, would lead to stable breathing and an open glottis.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

All procedures were performed in accordance with guidelines established by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia for the care and use of animals in experimental settings.9 These procedures were approved by the SPring-8/Japan Synchrotron Radiation Institute (JASRI) Animal Care (proposal no. 2016A0132) and Monash Medical Centre Animal Ethics Committee (application no. MMCA#2015/31). All experiments were conducted in experimental hutch 3 of beamline 20B2 in the Biomedical Imaging Centre at the SPring-8 synchrotron in Japan. Methodological reporting is provided as per the relevant ARRIVE guidelines.10

Experimental protocol

At 29 days of gestation (term ~32 days), pregnant New Zealand White rabbits (does) were sedated using propofol 1% (8 mg/kg i.v. bolus, followed by infusion at 15 mL/h, Rapinovet, Merck Animal Health) to insert a 22G catheter (BD 405254) into the subarachnoid space at the lumbar-sacral junction. A spinal block was performed by administering 0.5% bupivacaine (1 mg/kg) and 2% lignocaine (4 mg/kg) and confirmed by the absence of lower limb reflexes and muscle tone. The propofol infusion was then stopped and sedation continued with butorphanol (0.5 mg/kg/h) and midazolam (1 mg/kg/h) diluted in saline and infused i.v. Does received free flow oxygen via face mask (2 L/min; 60–80%) and their pedal reflexes, heart rates, arterial oxygen saturations and respiratory rates were monitored continuously. Rabbit kittens were exteriorised individually by caesarean section and temporarily remained attached to the umbilical cord. An oesophageal catheter was inserted so that the tip was in the mid-thoracic region to measure intrathoracic pressure changes during spontaneous breathing. Kittens were then fitted with a custom-made facemask and given naloxone (0.1 mg/kg; i.p. injection) to reverse the effects of maternally administered butorphanol, followed by caffeine to stimulate breathing (caffeine citrate, 20 mg/kg bolus, i.p.).11 The umbilical cord was clamped, and the kittens weighed before they were transferred into the imaging hutch where they were placed laterally (right-sided) on a heating pad and fitted with electrocardiogram (ECG) leads. The facemask was connected to a custom-built ventilator that incorporated a bias gas flow12 to apply a CPAP of 5 cmH2O. The oesophageal tube was connected to a pressure transducer (TNF-R, BD Dtxplus,TM DT, Mumbai), allowing the intrathoracic pressures and the kitten’s heart rate (from ECG) to be continuously recorded using a data acquisition system running Labchart v8 (Powerlab, ADInstruments, Sydney, Australia). Imaging commenced when the kitten was attached to the equipment and breathing spontaneously in a stable pattern. This usually required a brief period of tactile stimulation, prior to imaging onset.

All kittens received CPAP (5 cmH2O) via the face mask and were exposed to a sequence of gases with different oxygen levels: (i) air (21% O2), (ii) oxygen (100% O2), (iii) nitrogen (100% N2) and (iv) oxygen (100% O2) for a second time. As each kitten was exposed to the same sequence of gases, each kitten served as its own internal control. Kittens were exposed to each gas phase for a minimum of 3 min (maximum 8 min), with the exception of the nitrogen phase. Kittens only remained in nitrogen for as long as it took for the kitten develop apnea (absence of breathing for >10 s), at which point they were deemed to be sufficiently hypoxic and were then resuscitated in 100% O2 using iPPV (peak inflation pressure = 35 cmH2O and positive end expiratory pressure = 5 cmH2O), in conjunction with tactile stimulation. Once a stable breathing pattern was re-established, kittens were put back on CPAP (5 cmH2O) in 100% O2 for the final phase of the experiment. Throughout each gas phase, glottis patency (from the imaging), breathing patterns and heart rate were continuously recorded. The duration of each gas phase varied greatly between kittens and was dependent on the stability of breathing, the health of the kitten and/or whether the kitten required tactile stimulation. If the kittens required tactile stimulation to promote spontaneous breaths, imaging was ceased to allow researchers to enter the hutch and access the kitten, however the oesophageal pressure and heart rate recordings continued during this period.

Following delivery of the final kitten, the doe was euthanised via overdose of sodium pentobarbitone (>100 mg/kg, i.v., Somnopentyl, Kyoritsu Seiyak, Japan). Once imaging sequences were completed or kittens reached an ethical endpoint (absent breathing efforts despite resuscitative measures), kittens were removed from the hutch and euthanised via overdose of sodium pentobarbitone (>100 mg/kg, i.p., Somnopentyl, Kyoritsu Seiyak, Japan).

Phase contrast X-ray (PCX) imaging

A Hamamatsu ORCA flash C11440-22C camera, coupled to a 25 mm Gadox (P43) phosphor and tandem lens optics (effective pixel size of 15.3 μm2, 2048 × 2048 pixels), was used to image the head, neck (trachea and glottis) and upper thoracic cavity of rabbit kittens immediately after birth. Synchrotron radiation was tuned to 24 keV by a Si (111) monochromator, and kittens were placed 210 m downstream of the source. The kitten-to-detector distance was set to 2 m and images were acquired using 20 ms exposure times with a frame rate of 20 Hz. Flat field and dark current images were acquired at the end of each imaging sequence to correct for variations in beam intensity and detector dark current signal.

Glottis imaging and breathing pattern analysis

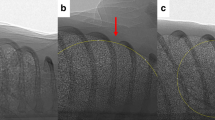

PCX images were compiled into a sequence of frames and viewed (unblinded) by an investigator (EC) to determine whether the glottis was open or closed immediately after birth during each gas phase (see Fig. 1). Data are expressed as the percentage of time the glottis was open in each consecutive 30 s interval (600 images analyzed per kitten per interval). Breathing rates (breaths/min) were derived from the oesophageal pressure catheter and were averaged over 30-s intervals in each gas phase. During the nitrogen phase, as the time taken to stop breathing was highly variable among kittens, the data from each kitten was aligned using the onset of apnea as the starting point. Thirty-second intervals were then analyzed backwards in time, from the point of apnea until the start of the nitrogen phase. Stable breathing patterns were defined as regularly occurring breathing efforts that were similar in frequency and amplitude (see Fig. 2).

a An open glottis, capable of facilitating gas flow down to the lower airways. b A closed glottis, which prevents gas flow from reaching the lower airways. The kitten is positioned laterally, with the cranial and caudal end of each kitten indicated on the left and right side of the image, respectively. The ‘Trachea’ and oesophageal ‘Tube’ have been indicated with arrows.

An oesophageal catheter (mid-thoracic region) was used to measure intrathoracic pressure changes during breathing efforts after birth in preterm rabbit kittens. Each inspiration produced a distinct negative change in pressure within the thorax (*). a A period of stable breathing with regularly occurring breathing efforts that had a similar frequency and amplitude. b A period of unstable breathing where breathing efforts were inconsistent in their frequency and amplitude and periods of apnea were commonly seen.

Statistical analysis

Glottis patency, breathing patterns and heart rate in each gas phase (excluding the nitrogen phase) were compared using a repeated measures mixed-effects model for both time and treatment (gas phase) effects. A minimum of four kittens had to contribute to each timepoint for it to be included in the analysis. When a significant treatment effect was observed, post hoc (Tukey’s) analysis was performed to compare the mean of all values in each gas phase (e.g., the mean of all values in Air was compared to the mean of all values in Oxygen). The nitrogen phase was excluded from the mixed-effects analysis due to the need to align the data between kittens using the onset of apnea as the starting point. These data were instead analyzed using a Pearson’s r correlation and a simple linear regression to analyze the relationship between glottis patency (%time open) and breathing rate during nitrogen exposure. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism v9 (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA) and p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were tested for normality and transformed if required. Data are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise specified.

Results

Animal data

Real-time PCX images and breathing recordings were collected from 26 preterm rabbit kittens (delivered from 10 does) supported with non-invasive respiratory support from birth. Kitten data were excluded from analysis if the kittens were non-viable (e.g., absent breathing efforts or presence of pneumothorax) or technical problems were encountered during imaging/recording (n = 11, summarised in Supplementary Fig. S1). Three kittens developed distended stomachs from the CPAP and so were excluded from the analysis due to the potential of the distension to impede breathing. The final analysis included images and recordings from 12 kittens, with an average weight of 34.8 ± 0.1 g (range: 21–44 g).

Effect of increasing oxygen exposure on glottis function and breathing patterns

Prior to imaging, significant tactile stimulation was required to establish spontaneous breathing and many kittens displayed unstable breathing patterns with regularly occurring apneas. All kittens began receiving CPAP in room air and imaging commenced when regular breathing efforts were present. Two out of 12 kittens were switched to 100% oxygen within 1 min of initiating CPAP in room air due to poor or absent breathing efforts, however the remaining 10 kittens were able to establish a breathing pattern in air. During the ‘air’ phase, the mean proportion of time the glottis was open for was 15.5 ± 1.3% (Fig. 3), with an average breathing rate of 11.3 ± 1.1 breaths/min (Fig. 4a) and heart rate of 130.6 ± 4.3 bpm (Fig. 4b).

The proportion of time the glottis was observed to be open (%Time open) was visually assessed using phase contrast X-ray imaging while preterm newborn rabbit kittens were exposed to room air, 100% oxygen, 100% nitrogen and 100% oxygen for a second time. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. During the nitrogen phase, the data were analysed retrospectively, with respect to time, starting with the point of apnea [A]. Grey bars that do not share a common letter indicate average values in the gas phases that are significantly different from each other (p < 0.0001; mixed effects analysis).

Breathing rate (BR; a) and heart rate (HR; b) were continuously recorded while preterm newborn rabbit kittens were exposed to room air, 100% oxygen, 100% nitrogen and 100% oxygen for a second time. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. During the nitrogen phase, the data were analysed retrospectively, with respect to time, starting with the point of apnea [A]. Grey bars that do not share a common letter indicate average values in the gas phases that are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05; mixed-effects analysis).

Switching from room air to 100% oxygen resulted in a significant increase in time that the glottis was open (15.5 ± 1.3% vs. 44.7 ± 1.8%, p < 0.0001, Fig. 3) and breathing patterns appeared more stable. Average breathing rates (18.1 ± 0.5 breaths/min) and heart rates (193.9 ± 4.8 bpm) also significantly increased in 100% oxygen compared to air (p = 0.0001 and p < 0.0001; Fig. 4a and b, respectively). An example of the change in glottis patency and breathing rate that occurred in a kitten exposed to 100% oxygen is presented in Fig. 4. In this example, the kitten’s glottis was patent for ~16% of the time whilst in room air. During this time, the glottis only opened briefly during inspiration but remained closed in between breaths (Fig. 5a). However, within 5 min of oxygen exposure, the glottis was open for 100% of the time throughout the entire breathing cycle (Fig. 5c). Overall, 83% (10/12) of kittens demonstrated an increase in the proportion of time the glottis was open from the end of the ‘air’ phase until the end of the first ‘oxygen’ phase. By the end of the first ‘oxygen’ phase, four out of 12 kittens demonstrated an open glottis for >80% of the time, two kittens demonstrated a glottis open between 20 and 80% of the time and six kittens demonstrated a glottis open for <20% of the time.

An oesophageal catheter (mid-thoracic region) was used to measure intrathoracic pressure changes during breathing efforts after birth. Breathing patterns were continuously recorded and the glottis was assessed for patency while the kitten was exposed to a continuous positive airway pressure in room air (21% oxygen) and then 100% oxygen. The specific times during the breathing cycle when the glottis was observed to be open has been highlighted in green and in pink when closed. In air (a), the glottis was predominantly closed and opened only briefly during inspiration (~16% of the time). When first exposed to 100% oxygen (b), breathing efforts after one minute were more frequent and the glottis was observed to be open for longer in-between breaths (~52% of the time). After being exposed to 100% oxygen for 5 min (c), breathing efforts were more frequent and the glottis was open throughout the entire breathing cycle (100% of the time).

Effect of removing oxygen on glottis function and breathing patterns

On average, it took kittens 4.7 ± 0.6 min (range: 1.8–8.2 min) to become apneic when exposed to 100% nitrogen and breathing patterns became increasingly unstable as the kittens progressed towards apnea. Once breathing ceased, the glottis in all kittens (100%; 12/12) was closed (Fig. 3). Heart rate also progressively declined as the kittens became apneic (101.8 ± 7.9 bpm at apnea vs. 201.5 ± 20.6 bpm at 5 min prior to apnea; Fig. 4b). The progressive decline in breathing rate and glottis patency throughout the ‘nitrogen’ phase were strongly correlated (r = 0.789, p < 0.0001; Fig. 6).

Preterm rabbit kittens were exposed to 100% nitrogen to deliberately induce apnea. The proportion of time the glottis was open (%Time open) was plotted against the average breathing rate (BR) until the point of apnea. The proportion of time the glottis was open was strongly correlated with BR (Pearson’s r correlation = 0.789). Simple linear regression is presented (dotted lines are 95% confidence intervals; R2 = 0.623, p < 0.0001).

Glottis function and breathing patterns following resuscitation in 100% oxygen

To restore spontaneous breathing efforts following nitrogen exposure, kittens required vigorous tactile stimulation combined with, on average, 1.1 ± 0.3 min of iPPV in 100% oxygen. In general, it only took three or four spontaneous breaths to sufficiently re-oxygenate the kittens and re-initiate regular spontaneous breathing, after which ventilation switched to CPAP. Two out of 12 kittens could not be resuscitated following the ‘nitrogen’ phase. The remaining 10 kittens rapidly achieved a similar glottis patency (44.7 ± 1.8% vs. 46.9 ± 1.6%, p = 0.81, Fig. 3) and similar breathing rates (18.1 ± 0.5 breaths/min vs. 15.5 ± 1.4 breaths/min, p = 0.21, Fig. 4a) compared to the first ‘oxygen’ phase. It was common for breathing rates to be highest when the kittens were receiving tactile stimulation, although when imaging began and the kittens could not be stimulated, breathing rates tended to reduce over time (Fig. 4a).

Discussion

The importance of understanding respiratory control in the newborn has now become a compelling issue due to the shift towards resuscitating infants at birth using non-invasive methods. It has long been assumed that iPPV is equally effective when applied via facemask as it is when applied directly to the lower respiratory tract via an endotracheal tube. However, this assumption is false and markedly underestimates the complexity of breathing control in the immediate newborn period. We used PCX imaging to investigate the relationship between glottis patency, breathing patterns and oxygenation in preterm newborn rabbit kittens. Our results confirm that breathing patterns and glottis function are closely related, whereby a decreased breathing rate and unstable breathing pattern are closely associated with a glottis that is closed between breaths and only opens during a breath.3 Further, these results highlight the inhibitory effect of hypoxia on newborn breathing patterns and the contribution of oxygenation to whether the glottis remains open or closed.

The primary focus of respiratory support for preterm infants in the delivery room is to aerate the lungs so that they can quickly take over the role of gas exchange. In spontaneously breathing infants, CPAP (applied non-invasively) is an important component of this respiratory support. By maintaining a constant pressure on the airways, CPAP helps to maintain end-expiratory lung volumes (functional residual capacity; FRC) and reduces the work of breathing in preterm infants, as their lungs are poorly compliant and prone to collapse during expiration. However, if their breathing efforts are insufficient, iPPV can be applied, but closure of the glottis can undermine the benefit of iPPV by obstructing airflow into the lower airways; a commonly reported issue in preterm infants.13,14,15,16 Airway obstruction due to the closure of the glottis has now been clearly demonstrated using laryngeal ultrasound in preterm newborns.2 In preterm rabbit kittens, we found that breathing patterns were more unstable when kittens were breathing room air and during this breathing pattern, the glottis only opened briefly during inspiration (see Fig. 5). As a result, iPPV could only transfer air into the lower airways if the inflation coincided with a breath, when the glottis was briefly open, otherwise it was ineffectual. This highlights the need to synchronise iPPV with spontaneous breathing activity when it is applied in the delivery room. Alternatively, a transient period of high-level CPAP may achieve the same benefit without having to synchronise the ventilation.17,18

Changing the inspired gas from air to 100% oxygen increased the stability of breathing patterns in preterm kittens, and the glottis remained opened for a significantly greater proportion of time. While this should provide more opportunity to deliver iPPV to the lung as the glottis was commonly open throughout the respiratory cycle, the glottis can still close, particularly to effect expiratory braking. Expiratory braking commonly occurs in the immediate newborn period and is thought to help slow lung deflation and defend end-expiratory lung volumes. Nevertheless, when breathing patterns are stable, iPPV is unnecessary and most probably counter-productive.

Respiratory control mechanisms in the immediate newborn period are highly complex, and the breathing responses to different types of stimuli are not well understood, particularly in preterm newborns with immature neural circuits.19 For example, the application of a face mask during resuscitation can activate receptors that signal via the trigeminal nerve and depress breathing efforts and cause bradycardia.20 While this is similar to hypoxia, the sensory and activation pathways are very different. On the other hand, tactile stimulation, caffeine and increasing oxygenation are known respiratory stimulants that promote breathing efforts in newborns,21,22 again through very different pathways. However, the effect of oxygen on newborn breathing is not likely to be a specific effect of oxygen per se. Instead, it mostly likely acts by preventing hypoxia, which is known to inhibit breathing via nuclei located in the upper lateral pons region of the brainstem.8 Instead, we have suggested that there is an oxygenation threshold, whereby increasing oxygen levels above this threshold have no further stimulatory effect and may indeed inhibit breathing,17 as has been observed clinically.23

The use of oxygen for preterm infants in the delivery room is still highly debated, although current recommendations suggest that the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) should be initially restricted to 0.21–0.3,24 followed by titration based on pulse oximetry targets. While the intention of this recommendation is to avoid potential injury associated with hyperoxia and oxidative stress, it may also have the unintended consequence of higher rates of hypoxia, inhibition of breathing and glottic closure. More recently, the initial use of high inspired oxygen levels (FiO2 1.0) in the delivery room, followed by rapid titration as the lung aerates, has been shown to promote breathing efforts, compared to the initial use of low FiO2 (0.3) in preterm infants <30 weeks gestation.22 The infants receiving an FiO2 of 1.0, achieved target oxygen saturations faster and had higher tidal volumes and minute ventilation immediately after birth, without an overall increase in oxygen exposure.22 This finding is consistent with and may explain the findings of a recent meta-analysis showing a potential reduction in mortality in preterm infants (<32 weeks gestation) when using high initial FiO2 (≥0.9) compared to low (≤0.3) and moderate (0.5–0.65) FiO2 in the delivery room.25

The inhibitory effect of hypoxia on breathing in the newborn was well documented in this study. The switch to breathing 100% nitrogen gradually induced hypoxia and inhibited breathing, causing apnea and bradycardia in these preterm kittens. The inhibitory effect of hypoxia on breathing in the fetus and newborn is well established and is present in all newborns, but gradually diminishes over the first few weeks after birth to eventually become stimulatory in older infants, children and adults.26,27 However, the time course for this change in “hypoxic sensitivity” in preterm infants is unknown and could be delayed.26 We found that the time between switching to nitrogen and the onset of apnea was very variable between kittens, which has numerous explanations, including the time taken for nitrogen to pass through the ventilator and fill the respiratory circuit for the kitten to breathe. In addition, we would expect kittens to have very different oxygenation statuses and thereby different oxygen reserves when the inspired gas was switched to nitrogen. As a result, even though the rate of oxygen depletion was likely to be similar between kittens, the time taken to reach the “hypoxic threshold”, below which oxygen levels are correlated with breathing activity, will vary between kittens. Unfortunately, it was not possible in this study to accurately measure arterial oxygenation in the preterm kittens using pulse oximetry.

While we did not formally assess the ability of tactile stimulation to reverse ongoing apnea, we found that tactile stimulation was essential to re-establish spontaneous breathing in apneic preterm kittens. This is consistent with our previous studies showing that tactile stimulation can increase breathing efforts in preterm infants28 and when applied during unstable breathing can avoid the onset of apnea.29 However, we were unable to provide regular tactile stimulation during imaging as investigators cannot enter the hutch during imaging. Our inability to provide tactile stimulation during imaging explains the relatively high number kittens that were excluded (n = 6) as independent, unstimulated breathing was required to complete the protocol. Indeed, while we could provide iPPV remotely, by itself, it was unable to restore spontaneous breathing, largely because the glottis was closed. While physical stimulation was not successful at restoring breathing in all kittens, we found it to be a highly effective method for promoting spontaneous breathing when provided.

It should be acknowledged that as the PCX images were captured at 20 Hz with an exposure time of 20 ms (the period between images was 30 ms), 600 ms of every second were not imaged. Thus, it is possible that the glottis may have opened between exposures and so was not captured in the images for our analysis. However, as the glottis must have been open for only a very short period of time under these circumstances, this would have a minimal impact on the calculation of the percentage of time that the glottis is open.

Conclusion

We have shown that a gradually increasing level of hypoxia induces unstable breathing patterns that eventually lead to apnea and closure of the glottis in preterm newborn kittens at birth. As hypoxia worsened, the inhibition of breathing increased as did the period that the glottis remained closed. In contrast, increasing oxygen exposure promoted spontaneous breathing and led to more stable breathing patterns where the glottis remained open for a greater proportion of time. As a result, we found a highly significant positive relationship between breath rates and percentage of time the glottis remains open. These findings highlight the importance of promoting a stable breathing pattern during the administration of non-invasive respiratory support and the need to avoid hypoxia. Restricting FiO2 levels in the immediate newborn period when the lung is only partially aerated could lead to hypoxia, the inhibition of breathing and closure of the glottis. However, the optimal oxygen therapy for preterm infants is unclear and warrants further investigation.

Data availability

All analyzed physiological and imaging data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Any raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. There are no restrictions on who may make this request.

References

Manley, B. J., Cripps, E. & Dargaville, P. A. Non-invasive versus invasive respiratory support in preterm infants. Semin. Perinatol. 48, 151885 (2024).

Heesters, V. et al. The vocal cords are predominantly closed in preterm infants <30 weeks gestation during transition after birth; an observational study. Resuscitation 194, 110053 (2023).

Crawshaw, J. R. et al. Laryngeal closure impedes non-invasive ventilation at birth. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 103, F112–f9 (2018).

Hooper, S. B. & Harding, R. Fetal lung liquid: a major determinant of the growth and functional development of the fetal lung. Clin. Exp. Pharm. Physiol. 22, 235–247 (1995).

Harding, R. & Hooper, S. B. Regulation of lung expansion and lung growth before birth. J. Appl Physiol. 81, 209–224 (1996).

Harding, R., Bocking, A. D. & Sigger, J. N. Upper airway resistances in fetal sheep: the influence of breathing activity. J. Appl Physiol. 60, 160–165 (1986).

Boddy, K. et al. Foetal respiratory movements, electrocortical and cardiovascular responses to hypoxaemia and hypercapnia in sheep. J. Physiol. 243, 599–618 (1974).

Gluckman, P. D. & Johnston, B. M. Lesions in the upper lateral pons abolish the hypoxic depression of breathing in unanaesthetized fetal lambs in utero. J. Physiol. 382, 373–383 (1987).

Australian Code for Responsible Conduct of Research. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council and Universities Australia; 2018.

Percie du Sert, N. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 40, 1769–1777 (2020).

Dekker, J. et al. Caffeine to improve breathing effort of preterm infants at birth: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr. Res. 82, 290–296 (2017).

Kitchen, M. J. et al. A new design for high stability pressure-controlled ventilation for small animal lung imaging. J. Instrum. 5, T02002–T02002 (2010).

Siew, M. L., van Vonderen, J. J., Hooper, S. B. & te Pas, A. B. Very preterm infants failing CPAP show signs of fatigue immediately after birth. PLoS ONE 10, e0129592 (2015).

van Vonderen, J. J. et al. Effects of a sustained inflation in preterm infants at birth. J. Pediatr. 165, 903–8.e1 (2014).

Schmölzer, G. M. et al. Airway obstruction and gas leak during mask ventilation of preterm infants in the delivery room. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 96, F254–F257 (2011).

Bizzotto D. et al. Impact of neonatal noninvasive resuscitation strategies on lung mechanics, tracheal pressure, and tidal volume in preterm lambs. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00236.2022. (2024).

Cannata E. R. et al. Optimising CPAP and oxygen levels to support spontaneous breathing in preterm rabbits. Pediatr. Res. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-03802-x. (2025).

Martherus, T. et al. High-CPAP does not impede cardiovascular changes at birth in preterm sheep. Front. Pediatr. 8, 584138 (2020).

Kuypers, K. et al. Reflexes that impact spontaneous breathing of preterm infants at birth: a narrative review. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 105, 675–679 (2020).

Kuypers, K. et al. Exerted force on the face mask in preterm infants at birth is associated with apnoea and bradycardia. Resuscitation 194, 110086 (2023).

Dekker, J. et al. Increasing respiratory effort with 100% oxygen during resuscitation of preterm rabbits at birth. Front. Pediatr. 7, 427 (2019).

Dekker, J. et al. The effect of initial high vs. low FiO(2) on breathing effort in preterm infants at birth: a randomized controlled trial. Front. Pediatr. 7, 504 (2019).

Saugstad, O. D., Rootwelt, T. & Aalen, O. Resuscitation of asphyxiated newborn infants with room air or oxygen: an international controlled trial: the Resair 2 study. Pediatrics 102, e1 (1998).

Wyckoff, M. H. et al. Neonatal Life Support: 2020 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Circulation 142, S185–s221 (2020).

Sotiropoulos J. X. et al. Initial oxygen concentration for the resuscitation of infants born at less than 32 weeks’ gestation: a systematic review and individual participant data network meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.1848. (2024).

Davey, M. G., Moss, T. J., McCrabb, G. J. & Harding, R. Prematurity alters hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory responses in developing lambs. Respir. Physiol. 105, 57–67 (1996).

Teppema, L. J. & Dahan, A. The ventilatory response to hypoxia in mammals: mechanisms, measurement, and analysis. Physiol. Rev. 90, 675–754 (2010).

Dekker, J. et al. Repetitive versus standard tactile stimulation of preterm infants at birth - a randomized controlled trial. Resuscitation 127, 37–43 (2018).

Cramer S. J. E. et al. The effect of vibrotactile stimulation on hypoxia-induced irregular breathing and apnea in preterm rabbits. Pediatr. Res. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03061-2. (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the SPring-8 synchrotron facility (Japan), which was granted by the SPring-8 Program Review Committee, for providing access to the X-ray beamline and associated facilities.

Funding

This research was supported by the Australian Research Council, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. We acknowledge travel funding provided by the International Synchrotron Access Program (ISAP), managed by the Australian Synchrotron and funded by the Australian Government. M. J. Kitchen was the recipient of an ARC Australian Research Fellowship (DP110101941). A. B. te Pas was recipient of a Veni-grant, The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), part of the Innovational Research Incentives Scheme Veni-Vidi-Vici. S.B. Hooper is a recipient of an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, Principal Research Fellowship. Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data: S.B.H., A.T.P., M.J.W., M.J.K., K.J.C., K.L., E.C., I.M.D., M.T., P.D.K., E.V.M., J.D. Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: I.M.D., E.C., S.B.H. Final approval of the version to be published: all authors

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Davies, I.M., Crameri, E., Wallace, M.J. et al. Hypoxia inhibits breathing and causes the glottis to close in preterm rabbit kittens at birth. Pediatr Res (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-04748-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-04748-w