Abstract

Background

Fortification of human milk for very preterm infants (VPIs) with alternatives to conventional bovine milk-based fortifiers remains minimally studied. This trial tested whether fortification with protein-rich bovine colostrum (BC) improves feeding intolerance and clinical variables in VPIs receiving enteral nutrition with a relatively slow advancement.

Methods

In this unblinded, two-centre, randomised, controlled trial (FortiColos CN), VPIs (gestational age, 26 + 0 to 31 + 6 weeks) were fed human milk fortified with BC (n = 74) or a conventional fortifier (CF, FM85, Nestlé, n = 72) for at least two weeks, starting when enteral feeding volume reached 80–100 mL/kg body weight/d. Incidence of feeding intolerance, nutrition intake, body growth, morbidities and clinical biochemical parameters were compared between the two groups.

Results

No statistically significant difference was found in the incidence of feeding intolerance or in most of the nutritional or body growth parameters (p > 0.05). All recorded morbidity incidences and haematological and blood biochemical parameters were also similar between groups. Amino acids (Phe, Pro, Ser, Tyr, Val) showed higher levels in the infants receiving BC.

Conclusions

BC appeared safe when used as a fortifier to human milk for VPIs with slow feeding advancement, but did not improve feeding tolerance or clinical variables.

Impact

-

Fortifying human milk with bovine colostrum (BC) in very preterm infants (VPIs) is safe but did not improve feeding tolerance, growth or clinical outcomes, compared with a conventional fortifier (CF), when used during slow enteral feeding advancement.

-

This study adds to the limited clinical evidence on the use of BC as a human milk fortifier in VPIs receiving enteral feeding with different feeding protocols.

-

The findings support the safety of BC as a human milk fortifier in VPIs but suggest limited short-term clinical benefits over currently used fortifiers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nutrient fortification is required for very preterm infants (VPIs, gestational age (GA) at birth < 32 weeks) in the first few weeks of life due to the deficiency in nutrients and energy in human milk, which is the preferred feed for VPIs. Fortification of human milk, including maternal milk (MM) and donor human milk (DM), with multi-nutrient fortifiers is typically conducted to increase protein intake in VPIs, thereby better supporting body growth and organ development.1 What fortifier product to use to best support growth and organ development, whilst minimising risk of clinical instability and comorbidities, remains debated. The possibility of using fortifiers derived from human milk or milk from cows and donkeys has been explored.2,3,4,5,6 Randomised control trials (RCTs) comparing a human milk-based fortifier (HMBF) and infant formula as a fortifier or a bovine milk-based fortifier (BMBF) for preterm infants showed no difference in incidence of feeding tolerance or in a composite outcome of necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), sepsis or death.2,5 One meta-analysis did not show a better effect of HMBF over BMBF7, whilst another indicated a lower NEC risk of HMBF but also lower body weight gain.8 A fortifier based on donkey milk may lower the risk of feeding intolerance, relative to BMBF,3 but its application potential remains to be determined. BMBF remains most widely used due to its relatively low cost and wide commercial availability.9 The association between BMBF and an increased risk of gut complications, such as feeding intolerance and NEC, remains uncertain due to conflicting evidence from previous studies.5,6,,7 Besides, concern persists that introducing bovine-derived formula may elevate the risk of gut complications in VPIs, relative to donor human milk.10 These results highlight the need for testing alternative fortifier products for VPIs.

Bovine colostrum (BC) has a high level of protein, immunoglobulins (IgGs), and many other bioactive components that are missing in the currently used BMBFs, including lactoferrin, oligosaccharides, milk fat globule membranes and bioactive peptides.11,12 These bioactive components exert diverse beneficial effects on neonatal development, including gut maturation, immunity and brain development, through different mechanisms.12 BC shows gut protective effects when fed alone or used as a fortifier to human milk in preterm pigs as a model for preterm infants in the first 1-2 weeks after birth.13,14,15,16 RCTs have also shown that BC used as the first feed for preterm infants may reduce the incidence of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) and sepsis, relative to infant formula.17,18 A study using a highly processed BC product showed no clinical benefits and even a tendency to adverse effects,19 while our previous trial using a mildly treated BC showed that BC was generally well tolerated by VPIs, yet the clinical benefits remained inconclusive.20 When BC was used as a fortifier to human milk on the background of a fast enteral feeding regime (n = 232), clinical benefits were marginal or absent, relative to a conventional fortifier (CF) based on hydrolysed bovine whey proteins.21,22 The inconsistent findings suggest that the effect of BC might depend on the specific product used and feeding regimen, and warrant further trials before clinical application.

Enteral feeding practices in the first weeks after preterm birth vary widely around the world (feed, starting time, and advancement rate).23 In certain clinics in the low- and middle-income countries, advancement rate of enteral nutrition tends to be slower than in the countries with high income,23,24 leading to longer time to reach full enteral feeding, which could delay gut maturation25 and increase the risk of infections.26 Under such circumstances, supplementing human milk with a protein-rich, immunomodulatory milk product, such as BC, might be particularly beneficial. On this background, this study aimed to test whether using a mildly treated BC product as a fortifier to human milk improved feeding tolerance, as a surrogate marker for gut maturation, nutrition intake, growth and clinical variables in VPIs with enteral nutrition advancement slower than in our previous trial.21

Methods

Trial design

The FortiColos CN trial (Bovine Colostrum as a Fortifier Added to Human Milk for Preterm Infants, clinicaltrials.gov: NCT03822104) was a two-centre, two-arm, unblinded, randomised, controlled trial aiming to test the effects of fortification of human milk with BC on feeding intolerance, growth, and safety, relative to a currently used fortifier. The trial was conducted at Shenzhen Bao’an Women and Children’s Hospital and Nanshan People’s Hospital in Shenzhen, China, where DM is accessible via an established donor milk bank24 or an intra-ward donation programme. The trial protocol was approved by local ethical committees (approval number: LLSC-2019-02-01). In the trial registration, eligible GA was misregistered as 30 + 6 weeks and starting intervention dose as 1 g/100 mL human milk due to an oversight stemming from the similarity between this trial and the FortiColos Denmark trial (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT03537365). The actual GA and starting intervention dose in practice are described below. These registration discrepancies did not compromise the objectives of the trial.

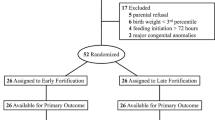

The sample size calculation is based on an expected difference in the incidence of feeding intolerance (defined below), 30% in the control group and 10% in the intervention group. To detect this difference with a power of 80% (α, 0.05; 2-sided test), a total of 59 infants were required in each group, leading to a total enrolment of 118 infants. Considering a drop-out rate of 5% and an inflation factor of 1.1 to account for multiple births, the final total sample size was 136.

Recruitment and randomisation

Infants born between GA 26 + 0 and 31 + 6 weeks and in need of nutrient fortification, as judged by attending neonatologists, were eligible. VPIs with major congenital anomalies and birth defects, subjected to gastrointestinal surgery prior to randomization, receiving infant formula prior to randomisation, or not ready to start fortification before postmenstrual age (PMA) 34 weeks, were excluded from the trial. Written and informed parental consent was obtained before randomisation. The recruitment started on 17 April 2019 and ended on 10 November 2021. Enroled infants across both participating units were randomised to receive either BC or a CF as a fortifier to human milk via a secure website hosted by the Odense Patient data Explorative Network (OPEN, www.open.rsyd.dk) at Odense University Hospital, Denmark. Infants from multiple births were assigned to the same treatment. Small for gestational age (SGA) was diagnosed based on the Actual Age Calculator of Fenton’s Growth Chart for Preterm Infants and defined as <10th percentile for body weight at birth.27

Intervention

For participating infants, DM was only used when MM was insufficient or unavailable. The BC powder used was from the first milkings of Danish dairy cows and provided by Biofiber-Damino (Gesten, Denmark) as sterilised powder in 10 g sachets following gentle, low-temperature pasteurization (63 °C, 30 min), gamma irradiation and spray drying.21 Detailed nutrition information of the BC and CF products is presented in Supplementary Table S1. PreNAN FM85 human milk fortifier (Nestlé, Vevey, Switzerland), containing moderately hydrolysed bovine whey proteins, was used in the CF group. Standardized fortification was adopted, i.e., no targeted or individualised fortification.28 The intervention started when enteral feeding reached 80–100 mL/kg body weight (WT)/d and gradually advanced. In the BC group, fortification started with 0.70 g BC (containing 0.35 g protein) per 100 mL human milk (MM or DM) on the first day of intervention, increasing to 1.4 g (0.70 g protein) on day 2, 2.1 g (1.05 g protein) on day 3, and 2.8 g (1.40 g protein) on day 4. In the CF group, it started with 1.0 g CF (0.35 g protein) per 100 mL human milk, increasing to 2.0 g (0.71 g protein) on day 2, 3.0 g (1.05 g protein) on day 3 and reaching 4.0 g (1.4 g protein) on day 4. The intervention lasted until infants reached PMA 35 + 6 weeks or were no longer in need of fortification due to sufficient growth, whichever came first. CF was given to the infants (in either group) who still required fortification after the planned intervention period of two weeks. The follow-up ended at hospital discharge when the infants met local discharge criteria or were requested by parents.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of having feeding intolerance for at least once during the intervention period. Feeding intolerance was defined as any withholding of fortification or enteral feeding. Secondary outcomes included nutrition parameters, such as nutrition status at the start and end of intervention, and hospital discharge, protein intake from the fortifier and enteral nutrition, time to reach enteral feed of 120 mL/kg WT/d (TEF120, d) and 150 mL/kg WT/d (TEF150, d). Anthropometric parameters included z-scores of WT, body length (BL) and head circumference (HC), referenced to the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants27 and growth velocity (g/kg wt/d) calculated with the exponential equation,29 and time to regain birth weight (d).30 Anthropometric changes between different time points were also assessed, including the ones from the start to the end of intervention, from the start of intervention to hospital discharge and from birth to hospital discharge. Comorbidities, including necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), late onset sepsis (LOS), bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), ROP and intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), and length of hospital stay were assessed. LOS is defined as clinical signs of infection >2 days after birth (from medical record, registered in the original data as LOS (+/-)) or antibiotic treatment for 5 days (or shorter than 5 days if the participant died) with or without one positive bacterial culture in blood or cerebrospinal fluid. NEC, BPD, ROP and IVH were diagnosed with local diagnostic criteria and relevant data were extracted from medical records. Paraclinical parameters, including haematological and blood biochemical parameters as well as plasma amino acid levels, on day 14 of intervention were also determined in available samples.

Data collection and analysis

Collected data were typed into a secure, online system, REDCap.31 The days in this trial was registered and shown as calendar days.

Outcomes were analysed on a modified intention-to-treat (mITT) basis, with only the infants who did start receiving the planned intervention being included for analysis.32 The CF group was set as the comparator.

The primary outcome, the feeding intolerance incidence, was analysed by a Cox regression analysis with 95% confidence interval (CI) and a p-value calculated by a Wald test. The modifying effect of the factor, hospital, on the effect of intervention was tested by comparing two models with and without the interaction of fortifier type and hospital. For anthropometric outcomes, baseline data were also adjusted for in the statistical models per the guidelines by the European Medicines Agency.33 For analysis of secondary outcomes, relevant statistical models were adopted with 95% CI and a p-value calculated. Baseline factors, such as GA and the hospital (Unit A or B), were adjusted for in all statistical analyses.

Pattern of missing values in parameters of blood biochemistry and amino acids was tested by a logistic regression model to estimate the probability of missingness by different covariates and a Little’s MCAR test34 using the naniar package.35 If the p-value of Little’s test was less than 0.05, the data were regarded as missing completely at random (MCAR), and a complete case analysis (CCA) was performed. If Little’s test indicated not MCAR and there were significant predictors, the data were seen as missing at random (MAR), and a weighted model using inverse probability weights was used. Negative results from both tests suggested missing not at random (MNAR), and a CCA and a sensitivity analysis averaging the estimates from models of differently imputed data with Bayesian linear regression from the mice package.36

In the calculation of protein intake, the protein concentration of MM was estimated as 1.6 g/100 mL.37 Protein concentration of DM (1.14 ± 0.27 g/100 mL) was based on the average values recorded at the Bao’an hospital. Protein concentration of BC was 1.4 g/2.8 g, and that of CF was 1.4 g/4.0 g, as previously reported.21

For the per-protocol analysis, only the infants who received the designated intervention for at least 14 days and those having the intervention stopped for reasons other than the intervention itself were included. All data analyses were conducted in R (Ver 4.4.0),38 interfaced with R Studio.39

Results

Recruitment

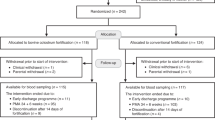

From both participating hospitals, 292 infants were assessed for eligibility (Fig. 1), 92 of which did not meet the inclusion criteria due to clinical conditions and treatment, such as nonelective surgical operation, severe lactose intolerance or severe feeding intolerance preventing routine nutrition regimen with MM/DM, and participation of 40 infants was declined by parents. In total, 160 infants were randomised to receive either BC (n = 79) or CF (n = 81) as a fortifier. Three infants did not receive any BC due to clinical conditions preventing fortification (lack of MM and DM or suspicion of gut complication), and two infants did not receive BC due to shipment difficulty of the BC product during the COVID-19 lockdown. In the CF group, four infants did not receive fortification due to preventing contraindications, one was discharged at parental request, two were transferred to another hospital, and two died before the start of planned intervention. The remaining 74 and 72 infants in the BC and CF group, respectively, were included in the mITT analysis. Further, due to reasons such as discharge at parental request and the need for surgery for NEC and death, three and two infants were lost to follow-up in the two groups, leaving 72 and 70 in the BC and CF groups for the PP analysis, respectively. Death cases were assessed by an independent data safety monitoring board by reviewing the medical records and none were judged to be related to the intervention. The majority of infants (n = 126) were recruited from one participating unit (Unit A). The PP results (Supplementary Tables S4–S6) were similar to the results from the mITT analysis. The following results are based on the mITT analysis, unless otherwise specified.

Characteristics of the included infants

Characteristics of the infants included in the mITT analysis at birth and before intervention are shown in Table 1. GA, the Apgar score at 5 min, anthropometrics including birth weight (BW), BL and HC and the number of infants that were male, SGA or singletons were similar in the two groups. Incidents of preeclampsia, preterm premature rupture of membrane (PPROM), chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, and treatment of antenatal steroids and intrapartum antibiotics were also similar. Anthropometrics at the start of intervention is shown in Table 2. No significant differences in z-scores of BW, BL or HC were observed. Only a small proportion of the trial participants were SGA (≤5%), precluding analysis in this subpopulation. This SGA rate is in accordance with the survey data from Unit A in 2019-2021 (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Primary outcome

In the included infants, 24 infants receiving BC (32%) and 21 infants receiving CF (29%) were diagnosed with feeding intolerance at least once during the intervention, respectively. No significant difference was found between the two intervention groups in the incidence of feeding intolerance as a dichotomous outcome (odds ratio, OR, 1.2 [0.6, 2.4], p = 0.66) or as a time-to-event outcome (hazard ratio, HR, 1.2 [0.6, 2.1], p = 0.61, Table 2). Further, no significant difference was found in the infants with GA less than 30 weeks or no less than 30 weeks (both p > 0.05). As a sensitivity analysis, the incidence of feeding intolerance was assessed in the infants from Unit A, and no significant difference was found (OR, 1.1 [0.5, 2.4], p = 0.77). No evidence of an interaction between hospital and the intervention was found (p = 0.68), suggesting that the intervention effect was consistent across the two hospitals.

Nutrition

Enteral feeding started on day of life (DOL) 2 [1,16] and 2 [1,10] (median [min, max]), and the intervention started on DOL 15 [6,44] and 14 [6,58] and ended on DOL 43 [11,76] and 40 [14, 115] in the infants receiving BC or CF, respectively. Infants receiving BC or CF were discharged on DOL 54 [26, 140] and 53 [29, 154], respectively (no significant differences, all p > 0.05, Table 2). The volume of enteral nutrition was similar between the two groups when the intervention started, 109 ± 20 and 112 ± 21 mL/kg WT/d in the BC and CF groups, respectively. Among the infants receiving BC and CF, 24 and 32 had DM as at least part of their enteral feed during the intervention period, respectively (p = 0.18, Chi-squared test).

All participants reached TEF120 within the intervention period, and TEF120 was similar between the infants receiving BC (21 ± 9 d) and the ones receiving CF (20 ± 10 d, p = 0.11). Regarding TEF150, 71 out of 74 infants receiving BC and 68 out of 71 infants receiving CF reached TEF150, and no difference was found (HR, 2 [−1, 5], p = 0.19). Infants receiving BC tended to receive more protein from the fortifier at the end of intervention (1.4 [0, 2.5] vs 1.4 [0, 1.4], g/100 mL feed, media [min, max], p = 0.07) and from enteral nutrition (4.2 ± 0.9 vs 3.9 ± 1.2, g/kg WT/d), p = 0.08) on day 14 of fortification, but the differences were minimal. More than 80% of infants in both groups needed fortification at the end of intervention and at hospital discharge and more than 80% of infants received only MM at the end of intervention and were on breastfeeding at hospital discharge. No significant difference was found between the two groups in any of these endpoints (all p > 0.05).

Growth parameters

Before the intervention, the infants to receive BC or CF had similar WT, BL and HC z-scores (all p > 0.05, Table 3). Infants receiving BC tended to have a shorter time to regain birth weight than those receiving CF (10 ± 3 d vs. 12 ± 8 d, p = 0.08). A fall in WT z-scores from birth was observed in both groups after the intervention (Supplementary Fig. S2). At the end of intervention, infants receiving BC tended to have lower WT z-scores (−1.41 ± 0.74 vs −1.33 ± 0.74, p = 0.13) but higher BL z-scores (−0.87 ± 0.87 vs −−102 ± 1.08, p = 0.06), relative to the infants receiving CF, but no significant difference was found in HC z-scores (p = 0.75). At hospital discharge, no difference was found in WT and HC z-scores, infants receiving BC tended to have lower BL z-score (−0.94 ± 0.96 vs −0.87 ± 0.90, p = 0.05), relative to the ones receiving CF. No significant difference was found between the two groups in the change of z-scores or GV in various time periods (Table 3). Infants receiving BC tended to have higher value in ΔBL z-scores from start to the end of intervention (−0.36 ± 0.67 vs −0.63 ± 0.86, p = 0.06) and from start of intervention to hospital discharge (−0.32 ± 0.79 vs −0.57 ± 0.83, p = 0.05).

Morbidities

No significant difference in the incidence of the morbidities registered was found between the infants receiving BC or CF (Supplementary Table S2), including NEC (4 vs 3, BC vs CF), LOS (32 vs 36), BPD (25 vs 25), ROP (9 vs 10) and IVH (4 vs 5, all p > 0.05). No difference in length of hospital stay was observed (p = 0.91, Table 2).

Haematology, clinical biochemistry and plasma amino acids

Infants receiving BC had lower level of blood urea nitrogen (BUN, 3.1 ± 1.6 vs 4.1 ± 3.7, mmol/L, p = 0.05) before intervention, higher level of haemoglobin after one week of fortification (8.4 ± 1.0 vs 8.0 ± 1.0, mmol/L, p = 0.03), higher phosphate level (2.2 ± 0.4 vs 2.0 ± 0.3, mmol/L, p = 0.01) and a tendency to lower sodium level (134.6 ± 2.8 vs 136.0 ± 2.5, mmol/L, p = 0.005) after two week of intervention than the ones receiving CF (Table 4). On day 14 of intervention, plasma levels of two essential amino acids (phenylalanine and valine) and three nonessential ones (proline, serine and tyrosine) were higher in the infants receiving BC than those in infants receiving CF (FDR-corrected p < 0.05, Supplementary Table S3).

Discussion

In this trial, enteral feeding started relatively late (median DOL 2), and the advancement was slower (TEF120, DOL 21), relative to our FortiColos DK trial (TEF160, DOL 8-9).21 Both fortification groups showed similar incidence of feeding intolerance, nutrition intake, body growth and morbidities as well as similar haematological and blood biochemical parameters and plasma amino acid profile after two weeks of intervention.

Feeding intolerance and nutritional outcomes

In this trial, fortification started when enteral feeding reached around 110 mL/kg WT/d (DOL 14), which is around one week later than in our previous trial (FortiColos DK, 150 mL/kg WT/d, DOL 8).21 Whether early initiation of fortification before full enteral feeding will increase the risk of feeding intolerance remains under debate.40,41 On the background of the late and slowly advanced enteral feeding in this trial, fortification with BC did not improve feeding tolerance in the whole trial population, nor in the subgroups of GA, less or no less than 30 weeks (Table 2). Similar to our findings, various fortifiers, including products based on human, bovine4,42 and donkey milk,3 showed similar effects on feeding intolerance or interruptions. This suggests that the source of fortifiers might not markedly affect feeding intolerance, which could be, at least partially, due to the fact that fortifier only contributes about 20% of the nutrient/protein content of the enteral nutrition.43

Assessing feeding intolerance across different studies is often difficult due to the different definitions adopted in different trials. The definition of feeding intolerance used in this trial is less strict than the one including a pause of enteral nutrition for a certain time with or without assessment of gastric residual.40,44 Our definition enables capturing any feeding disruption, which is important to evaluate when testing a new fortifier, such as BC.

Both BUN and creatinine levels decreased over the intervention period, as often observed in preterm infants,45 in part due to the changes in protein metabolism and kidney clearance. The higher levels of BUN and creatinine found in infants receiving BC before the start of fortification may be due to the coincidental higher intake of protein from the higher proportion of MM in this group. However, the missing registration of daily enteral feed precludes confirmatory statistical analysis. Similar to the findings from the FortiColos DK trial, infants receiving BC in the current trial tended to receive more protein than those on CF in the 2nd week of fortification (Table 2). This may be due to the difference in protein digestibility of BC (intact casein and whey protein) and CF (partially hydrolysed whey protein). These factors may have also contributed to the higher plasma level of amino acids, including phenylalanine, valine, and tyrosine, observed in infants receiving BC (Table S3). Similar to the findings in our previous study20 and the FortiColos DK trial,21 the level of tyrosine in this trial is higher in infants receiving BC. How proteins from enteral nutrition, including fortifier, affect the plasma amino acids and their possible clinical impact on growth and development is not clear.

In this trial, infants receiving BC showed higher plasma levels of phosphate than those receiving CF, which contains a higher level of phosphorus. In contrast, infants receiving BC in the DK trial required stronger supplementation to reach similar blood levels of phosphorus as the infants on CF.46 This suggests the difference between enrolments or the practice in the two trials, but it’s hard to pinpoint to specific factors. Collectively, these results suggest that it is important to monitor and adjust phosphorus levels when using BC as a novel fortifier. Conversely, lower sodium levels in infants receiving BC were observed in both trials, and this could be due to the lower levels of sodium in the BC product, relative to CF.21 Yet, in neither of the trials were the levels below the hyponatremia threshold (135 mmol/L).47

Relative to the FortiColos DK trial, the current trial had a larger proportion (>80%) of infants needing fortification at the end of intervention and hospital discharge. This suggests a large room for an increase in enteral feeding advancement at the participating hospitals from the existing ~6 mL/kg/d to an increment of 30–40 mL/kg/d, which has been shown safe.48

Growth outcomes and morbidities

In this trial, infants in both groups reached their birth weight before the intervention started. Infants receiving BC tended to have a shorter time to regain birth weight, relative to those receiving CF, which could be due to the higher MM intake in infants receiving BC. A fall in anthropometric z-scores from birth or the start of intervention in both groups of infants was found, similar to the FortiColos-DK trial.21 Despite the use of fortifiers improving body weight gain,49 few trials have documented positive effects on anthropometric z-scores during hospitalisation, regardless of the growth chart used, manifesting the difficulty in supporting the growth of VPIs in the first weeks after birth. Similar to our findings, a previous open-label trial showed no difference in GV between infants receiving a preterm formula as a fortifier or a BMBF.2 Similarly, comparisons between an HMBF and a BMBF2, as well as whey-only fortifier vs other fortifiers4 showed similar effects on body growth. Of note, the infants receiving BC in this current trial had higher BL z-scores at the end of intervention and at hospital discharge. This is likely to be due to the intervention, as there was also a smaller drop in BL z-score from the start to the end of intervention as well as from the start of intervention to discharge, but not between birth and discharge (Table 3). However, it’s difficult to attribute this difference to specific components of the BC product or the intervention.

Incidents of morbidities were included as safety outcomes in this trial, despite the low power to detect differences. None of them showed any statistical difference between the intervention groups, as in many other studies.2,4,42 A meta-analysis with multiple studies and trials is needed to address this specific research question.

Limitations

Due to the brown hue of the BC-fortified human milk, blinding would have required extensive logistic efforts and training of staff and was deemed impractical and nonessential. This would have introduced potential bias from the medical staff when recording clinical results. Further, protein intake was assessed based on estimated/empirical data, not actual values, which may have caused imprecision in intake values. There were only two participating units in this trial, and differences between the two units were found in many aspects of clinical practice and in various parameters. However, our statistical analysis showed no modifying effect of trial unit on the intervention effect on the primary outcome. Due to the relatively slow enteral feeding advancement in both units, the results from this trial might not be extrapolated to other units with faster feeding. However, considering previous reports from the FortiColos DK trial demonstrating similar results, the findings don’t appear to be dependent on the advancement of enteral feeding.

Conclusion

This trial showed that using BC as a human milk fortifier appears feasible and safe but does not improve feeding tolerance or clinical variables in VPIs receiving slowly advancing human milk as enteral feeding after preterm birth. Our findings support the feasibility and safety of using BC as a human milk fortifier, as evidenced by adequate growth and enteral intake. However, clinical biochemistry and plasma amino acid profiles suggest that modifications to the protein composition and additional micronutrient supplementation may be required. Any such adjustments must carefully consider the potential impact of industrial processing on the bioactive components of BC that have potential in supporting gut and metabolic development in preterm infants.

Data availability

Data described in the manuscript, code book and analytic code will be made available upon request, pending application and approval. For future use, the collected dataset has been anonymised and stored in secure environments at Shenzhen People’s Hospital, Shenzhen, China and University of Copenhagen, Denmark. The data handling and storage are in compliance with the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

References

Arslanoglu, S. et al. Fortification of Human Milk for Preterm Infants: Update and Recommendations of the European Milk Bank Association (EMBA) Working Group on Human Milk Fortification. Front. Pediatr. 7, 76 (2019).

Chinnappan, A. et al. Fortification of breast milk with preterm formula powder vs human milk fortifier in preterm neonates: a randomized noninferiority trial. JAMA Pediatr. 175, 790–796 (2021).

Bertino, E. et al. A Novel Donkey milk–derived human milk fortifier in feeding preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 68, 116–123 (2019).

Han, J. et al. Using a new human milk fortifier to optimize human milk feeding among very preterm and/or very low birth weight infants: A Multicenter Study in China. BMC Pediatr. 24, 61 (2024).

Jensen, G. B. et al. Effect of human milk-based fortification in extremely preterm infants fed exclusively with breast milk: a randomised controlled trial. eClinicalMedicine 68,102375 (2024).

Jordan, K. W., Rooy, L. D., Richards, J. & Kulkarni, A. Bovine-based breast milk fortifier and neonatal outcomes in premature infants of <32 weeks gestational. Age. Infant 19, 14 (2023).

Premkumar, M. H., Pammi, M. & Suresh, G. Human milk-derived fortifier versus bovine milk-derived fortifier for prevention of mortality and morbidity in preterm neonates. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.11, CD013145 (2019).

Ananthan, A., Balasubramanian, H., Rao, S. & Patole, S. Human milk–derived fortifiers compared with bovine milk–derived fortifiers in preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 11, 1325–1333 (2020).

Mimouni, F. B. et al. The use of multinutrient human milk fortifiers in preterm infants: a systematic review of unanswered questions. Clin. Perinatol. 44, 173–178 (2017).

Quigley, M., Embleton, N. D. & McGuire, W. Formula versus donor breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2, CD004210 (2018).

Chatterton, D. E. W., Nguyen, D. N., Bering, S. B. & Sangild, P. T. Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms of Bioactive Milk Proteins in the Intestine of Newborns. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 45, 1730–1747 (2013).

Sangild, P. T., Vonderohe, C., Melendez Hebib, V. & Burrin, D. G. Potential Benefits of Bovine Colostrum in Pediatric Nutrition and Health. Nutrients 13, 2551 (2021).

Sun, J. et al. Human Milk Fortification with Bovine Colostrum Is Superior to Formula-Based Fortifiers to Prevent Gut Dysfunction, Necrotizing Enterocolitis, and Systemic Infection in Preterm Pigs. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 43, 252–262 (2019).

Sun, J. et al. Nutrient fortification of human donor milk affects intestinal function and protein metabolism in preterm pigs. J. Nutr. 148, 336–347 (2018).

Shen, R. L. et al. Early gradual feeding with bovine colostrum improves gut function and NEC resistance relative to infant formula in preterm pigs. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 309, G310–G323 (2015).

Rasmussen, S. O. et al. Bovine Colostrum Improves Neonatal Growth, Digestive Function, and Gut Immunity Relative to Donor Human Milk and Infant Formula in Preterm Pigs. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 311, G480–G491 (2016).

Farag, M. M. et al. Do Preterm Infants’ Retinas Like Bovine Colostrum? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ital. J. Pediatr. 50, 218 (2024).

Ismail, R. I. H. et al. Gut Priming with Bovine Colostrum and T Regulatory Cells in Preterm Neonates: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatr. Res. 90, 650–656 (2021).

Balachandran, B. et al. Bovine Colostrum in Prevention of Necrotizing Enterocolitis and Sepsis in Very Low Birth Weight Neonates: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial. J. Trop. Pediatr. 63, 10–17 (2017).

Juhl, S. M. et al. Bovine Colostrum for Preterm Infants in the First Days of Life: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 66, 471–478 (2018).

Ahnfeldt, A. M. et al. Bovine Colostrum as a Fortifier to Human Milk in Very Preterm Infants – a Randomized Controlled Trial (Forticolos). Clin. Nutr. 42, 773–783 (2023).

Kappel, S. S. et al. A Randomized, Controlled Study to Investigate How Bovine Colostrum Fortification of Human Milk Affects Bowel Habits in Preterm Infants (Forticolos Study). Nutrients 14, 4756 (2022).

de Waard, M. et al. Time to Full Enteral Feeding for Very Low-Birth-Weight Infants Varies Markedly among Hospitals Worldwide but May Not Be Associated with Incidence of Necrotizing Enterocolitis: The Neomune-Neonutrinet Cohort Study. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 43, 658–667 (2019).

Wu, T. et al. Availability of donor milk improves enteral feeding but has limited effect on body growth of infants with very-low birthweight: Data from a historic cohort study. Maternal Child Nutr. 18, e13319 (2022).

Young, L., Oddie, S. J. & McGuire, W. Delayed introduction of progressive enteral feeds to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 16, CD001970 (2022).

Zingg, W., Tomaske, M. & Martin, M. Risk of parenteral nutrition in neonates—an overview. Nutrients 4, 1490–1503 (2012).

Fenton, T. R. & Kim, J. H. A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatr. 13, 59 (2013).

Fabrizio, V. et al. Individualized versus standard diet fortification for growth and development in preterm infants receiving human milk. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.11, CD013465 (2020).

Patel, A. L. et al. Calculating postnatal growth velocity in very low birth weight (VLBW) premature infants. J. Perinatol. 29, 618–622 (2009).

Cormack, B. E. et al. Comparing apples with apples: it is time for standardized reporting of neonatal nutrition and growth studies. Pediatr. Res. 79, 810–820 (2016).

Harris, P. A. et al. The Redcap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 95, 103208 (2019).

Kahan, B. C., White, I. R., Edwards, M. & Harhay, M. O. Using Modified Intention-to-Treat as a Principal Stratum Estimator for Failure to Initiate Treatment. Clin. Trials 20, 269–275 (2023).

Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Guideline on adjustment for baseline covariates in clinical trials. European Medicines Agency. 6–7 (2015).

Little, R. J. A. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 83, 1198–1202 (1988).

Tierney, N. & Cook, D. Expanding tidy data principles to facilitate missing data exploration, visualization and assessment of imputations. J. Stat. Softw. 105, 1–31 (2023).

van Buuren, S. & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. Mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 45, 1–67 (2011).

Ren, Q. et al. Longitudinal Changes in Crude Protein and Amino Acids in Human Milk in Chinese Population: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 70, 555–561 (2020).

R. Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. (2013).

R. Studio Team. R Studio: Integrated Development for R. Boston, MA: RStudio, Inc. (2012).

Zhang, T., Luo, H., Wang, H. & Mu, D. Association of human milk fortifier and feeding intolerance in preterm infants: a cohort study about fortification strategies in Southwest China. Nutrients 14, 4610 (2022).

Thanigainathan, S. & Abiramalatha, T. Early fortification of human milk versus late fortification to promote growth in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 29, CD013392 (2020).

O’Connor, D. L. et al. Nutrient Enrichment of Human Milk with Human and Bovine Milk–Based Fortifiers for Infants Born Weighing <1250 G: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 108, 108–116 (2018).

Brown, J. V. et al. Multi-nutrient fortification of human milk for preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6, CD000343 (2020).

Ozer Bekmez, B. et al. Antenatal neuroprotective magnesium sulfate in very preterm infants and its association with feeding intolerance. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 77, 597–602 (2023).

Weintraub, A. S., Blanco, V., Barnes, M. & Green, R. S. Impact of renal function and protein intake on blood urea nitrogen in preterm infants in the first 3 weeks of life. J. Perinatol. 35, 52–56 (2015).

Simonsen, M. B. et al. Mineral supplementation for very preterm infants fed fortified human milk. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 78, 1389–1397 (2024).

Bischoff, A. R., Tomlinson, C. & Belik, J. Sodium intake requirements for preterm neonates. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 63, e123–e129 (2016).

Oddie, S. J., Young, L. & McGuire, W. Slow advancement of enteral feed volumes to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8, CD001241 (2021).

Mills, L. et al. Preterm formula, fortified or unfortified human milk for very preterm infants, the premfood study: a parallel randomised feasibility trial. Neonatology 121, 222–232 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank all participating infants and their parents in the study.

Funding

The study was financially supported by the Innovation Fund Denmark (6150-00004B), University of Copenhagen and Biofiber Damino A/S (Vejen, Denmark). The funding sources had no involvement in the conception or design of the study; in its execution or provision of materials; in the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the drafting, critical revision, or approval of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the work for publication. Open access funding provided by Copenhagen University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.T.S., Y.L., G.Z., and P.Z. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study. H.Y.H., L.Z., Z.H., X.L., and X.Y. were involved in data collection and investigation. P.Z. and P.P.J. curated the data, while P.P.J. conducted the formal analysis. S.M. and G.Z. provided software support. X.L., P.Z., P.T.S., and G.Z. supervised the project. P.P.J. drafted the original manuscript, and P.P.J., P.Z. and P.T.S. contributed to manuscript review and editing. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

This study is partially financially supported by Biofiber Damino A/S, a Danish company that donated the bovine colostrum used for the study. University of Copenhagen holds a patent (Eur. Patent no. EP2858653A1) on the use of bovine colostrum for preterm infants. Per Torp Sangild, listed as the sole inventor, has declined any share of potential revenue arising from the commercialisation of such a patent. Other authors have no conflicts of interest or financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Consent statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethical committee. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participants involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, PP., Huang, HY., Zhao, L. et al. Bovine colostrum as a human milk fortifier for very preterm infants with slow feeding advancement: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Res (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-026-04768-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-026-04768-0