Abstract

Background

The lack of centralized pediatric critical care data in Kuwait has limited benchmarking, outcome evaluation, and resource planning. This study describes the development and implementation of Kuwait’s first nationwide PICU registry and evaluates its feasibility and early utility.

Methods

A centralized registry was implemented across seven governmental PICUs serving over 870,000 children. Demographics, diagnoses, interventions, outcomes, and infection data were retrospectively collected at discharge by site coordinators. Data were entered into a secure, encrypted platform using de-identified records and role-based access, with centralized validation performed every tercile.

Results

During the implementation phase, 2086 of 2364 admissions were captured. Registry accuracy compared with manual admission logs was 88.2%, demonstrating feasibility and data reliability. Inter-hospital variability in clinical practices and resource utilization was identified. The registry also enabled early detection of infection trends and supported proactive staffing and equipment planning.

Conclusion

Kuwait’s national PICU registry is feasible, reliable, and operationally effective. It addresses critical data gaps, enhances transparency, supports evidence-based decision-making, and provides a foundation for national quality improvement and future benchmarking initiatives.

Impact

-

Demonstrates feasibility, reliability, and operational effectiveness of a national PICU registry in real-world pediatric critical care.

-

Enables early detection of infection trends and supports strategic planning for staffing and equipment.

-

Presents one of the first national PICU registry models in the Middle East, addressing fragmented data systems.

-

Offers practical strategies for standardization, data validation, and inter-hospital coordination, supported by physician champions and stakeholder engagement.

-

Bridges critical data gaps, strengthens quality monitoring and benchmarking, and provides a scalable framework for broader pediatric specialties and international research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) are the cornerstone hospital zones for managing critically ill children, where timely interventions and coordinated care can significantly influence outcomes.1 However, delivering consistent, high-quality care at a multi-centered level requires more than clinical skill, demanding access to integrated, standardized data.2 Without a unified system, differences in practices, outcomes, and resource use often go unnoticed, limiting the ability to identify performance gaps or implement national improvements.3 In recent years, healthcare systems have increasingly recognized the value of centralized data registries as strategic tools for enhancing care delivery, monitoring quality, and driving evidence-based improvements in critical care settings.4,5 A well-structured national registry not only supports the standardization of care processes but also facilitates benchmarking, transparency, and accountability among healthcare institutions.6

Establishing a multicenter data registry at the national level within the field of pediatric critical care presents a complex set of challenges that span technical, operational, and organizational domains.7,8,9 Variations in documentation standards, electronic health record systems, and data entry practices across institutions can hinder consistency and interoperability. Ensuring uniformity in variable definitions, coding, and data formatting requires significant coordination and consensus among clinical and administrative stakeholders.9,10 Additionally, recruiting and training dedicated personnel at each site to ensure accurate and timely data entry demands sustained institutional commitment.11 Regulatory and ethical considerations related to patient privacy, data ownership, and informed consent must also be carefully navigated, particularly in pediatric populations.12 Furthermore, securing long-term funding, establishing centralized data governance, and maintaining stakeholder engagement across geographically dispersed centers are essential yet often resource-intensive undertakings that require national leadership and a clear strategic vision.13

In Kuwait, governmental general PICUs comprise seven sites (Adan Hospital, Amiri Hospital, Farwaniya Hospital, Mubarak Alkabeer Hospital, Sabah Hospital, Jahra Hospital, Jaber Al-Ahmad Hospital) with a total bed capacity of 123, serving an estimated 870,520 children aged 14 years and younger within a total population of approximately 5.10 million.14 Despite this capacity, pediatric critical care services continue to face persistent challenges, particularly due to fragmented data collection systems and the lack of standardized performance indicators. Each PICU operated in relative isolation, relying on separated institutional documentation systems that varied in scope and accuracy. This lack of integration hindered national-level analysis, delayed quality initiatives, and reduced the capacity for benchmarking against international standards. To address these challenges, the Kuwait Pediatric Intensive Care Taskforce Group established a nationwide registry in April 2022. The goal was to create a centralized platform that collects, harmonizes, and analyzes data from all PICUs across the country. The registry serves multiple purposes: it enables ongoing monitoring of clinical outcomes, facilitates inter-hospital comparisons, and supports strategic planning in areas such as staffing, protocols, and resource utilization. More importantly, the registry lays the groundwork for evidence-based decision-making and continuous quality improvement.15 By aligning national efforts, the registry marks a significant step toward advancing pediatric critical care in Kuwait. This paper presents the design, implementation, and challenges of establishing the Kuwait PICU Registry, highlighting its potential to enhance care delivery and support national health priorities.

Materials and methods

A standardized, centralized registry system was implemented across all governmental PICUs in Kuwait as part of a national initiative to unify and monitor pediatric critical care practices. The system was designed to collect essential clinical data in a consistent and structured format from each participating site (Table 1). Captured variables included patient demographics, discharge diagnosis, type and timing of respiratory interventions, duration of PICU stay, and clinical outcomes. Data from all participating PICUs were entered into the system retrospectively and subsequently compiled and extracted every tercile for analysis by the central analytical team. The registry focused on a predefined set of key performance indicators relevant to pediatric critical care. These included the frequency and type of invasive procedures, respiratory support modalities (e.g., mechanical ventilation, non-invasive ventilation, high-flow oxygen), patterns of antimicrobial usage, and microbiological culture results.

To ensure patient confidentiality and data protection, registry data were de-identified at the point of data entry. Each record was assigned a hashed identifier generated using one-way encryption with a salt embedded in the algorithm, preventing reverse-engineering of the original information. Access to the registry platform was restricted to authorized personnel only, with each user assigned a unique, password-protected account. The system was hosted on a secure, encrypted server managed in accordance with national health data governance policies. Role-based access controls were implemented to limit user permissions based on specific responsibilities, ensuring a clear separation of functions related to data entry, analysis, and oversight. The Principle of Least Privilege (POLP) was strictly enforced, whereby users were granted access only to data from their respective hospitals and only to the functions necessary for their role—whether viewing, editing, or adjusting records.16 Ethics approval was obtained from the Ministry of Health (MOH) Institutional Review Board, Kuwait (Approval No. 2594/2024).

Process mapping

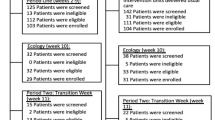

We developed a concise process map (Fig. 1) to visualize the end-to-end registry workflow (from bedside case identification through data entry, automated validation, and central curation) while explicitly assigning responsibilities to each actor. Hospital teams identify eligible cases, enter the data, align documentation with registry definitions, coordinate with unit champions, and resolve data queries to meet completeness and timeliness targets. A designated physician served as the site coordinator, responsible for retrospectively entering patient data daily at the time of discharge from patients’ medical files. To facilitate successful implementation, a physician champion with dual clinical and technical expertise was appointed to provide strategic oversight, promote shared ownership, and maintain execution fidelity. This champion model is supported by evidence linking such roles to improved project outcomes.17,18 Then, the registry core unit maintains the database architecture, designs the electronic Case Report Forms (eCRFs), manages secure data transfers, implements validation rules, delivers training, issues periodic reports, and serves as the liaison between participating sites and oversight authorities. Quality auditor performs independent checks against source records and manual censuses to verify case ascertainment, flag missing or implausible values, and provide structured feedback to sites, ensuring data is reliable for downstream use. The governance body (the Kuwait Pediatric Intensive Care Taskforce Group) sets strategy, defines data-access policies, assures ethical and legal compliance, adjudicates methodological changes, oversees sustainability, and aligns the registry with national health priorities while supporting dissemination. The mapping exercise exposed bottlenecks, role overlaps, and potential delays, prompting pre-launch corrections; decision nodes and validation loops were embedded to strengthen accuracy and streamline feedback. This living map now underpins ongoing monitoring of efficiency.

Stakeholder mapping

Parallel to workflow design, stakeholder mapping was undertaken to secure broad engagement and effective governance. Using a power–interest matrix, stakeholders were classified by their influence and level of engagement: regulators and Head of PICUs were recognized as key decision-makers requiring continuous involvement, while frontline clinicians and data managers were prioritized as high-interest groups critical for daily execution. By aligning registry goals with stakeholder expectations, the initiative gained both legitimacy and sustainability, ensuring that the registry became a shared national resource rather than a project limited to a single institution.

Quality improvement (QI) frameworks

The registry was developed and scaled using formal QI methodologies, incorporating the Model for Improvement and iterative Plan–Do–Study–Act (PDSA) cycles. Table 2 summarizes the timeline followed during the implementation phase. In the planning phase, core indicators and data-collection protocols were defined and piloted within selected units. This was followed by a targeted implementation phase, where small-scale testing was conducted to evaluate workflow feasibility and operational clarity. During these pilots, iterative PDSA cycles were used to systematically refine the system: in the Plan stage, the core unit and site coordinators identified uncertainties in definitions, workflow steps, and validation thresholds; in the Do stage, updated electronic Case Report Forms (eCRFs) and revised procedures were trialed in multiple PICUs; in the Study stage, completeness reports, validation-error logs, and structured staff feedback were analyzed to assess data quality, usability, and feasibility; and in the Act stage, modifications were incorporated into the registry architecture, variable dictionary, validation rules, and training materials. Multiple rapid cycles enabled the team to address bottlenecks, streamline processes, and ensure operational reliability. These refinements strengthened data consistency across sites, allowed early identification of care variations, and supported the timely detection of infection trends nationwide—facilitating proactive governmental planning to mitigate potential PICU surges.

Data accuracy validation

To assess the accuracy of the registry, a structured validation audit was conducted in which each submitted case was cross-checked. A quality auditor independently reviewed all submitted entries for completeness and correctness, manually verifying the full set of variables. Accuracy was calculated at the entry level as the proportion of registry cases in which all recorded fields matched the values identified through manual audit checks. Discrepancies were categorized into predefined error types, including transcription errors, missing values, and misclassified variables. For any discrepancy identified, a standardized correction workflow was applied: flagged entries were returned to the site coordinator for clarification, corrected data were resubmitted into the system, and recurring error patterns were communicated through structured feedback reports.

Results

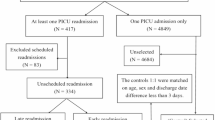

The initial phase of the registry encompassed seven government-operated general PICUs, compiling comprehensive data recorded in 2023 (Fig. 2). During the 2023 accuracy assessment, the registry captured 2,086 of 2,364 admissions recorded in manual logs, yielding an overall concordance rate of 88.2% (Table 3). In this study, accuracy denotes the concordance between registry-entered cases and the manually reviewed admission census. Accuracy varied across hospitals, with Sabah Hospital demonstrating the highest concordance at 96.0%, followed closely by Amiri (95.3%) and Farwaniya (94.3%) Hospitals. In contrast, Jahra and Adan Hospitals reported lower accuracy rates of approximately 81%.

Bed capacity across hospitals ranged from 4 beds at Amiri Hospital to 24 beds each at Adan and Jahra Hospitals, with a total of 123 beds included in the registry network. An annual report is shared with all PICU heads, detailing key metrics such as resource utilization, equipment usage, length of stay, and ventilator days (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The successful implementation of the Kuwait Pediatric Critical Care Registry highlights the importance of strategic team formation and quality improvement frameworks. The registry team prioritized the selection of key stakeholders, including clinical experts, technical specialists, and strong leadership, to drive the initiative forward.18 This multidisciplinary approach ensured that expertise in both medical care and data management was harmonized to produce meaningful improvements. From creating a sense of urgency to anchoring the registry within the culture of pediatric critical care, each step was pivotal in fostering collaboration, removing barriers, and ensuring the sustainability of the initiative. The registry’s ongoing influence in clinical guideline refinement and inter-hospital knowledge sharing underscores the value of systematic data-driven approaches to improving patient care.4,19 The registry has bridged long-standing data gaps within Kuwaiti PICUs, establishing a foundation for ongoing performance monitoring. Enhanced inter-hospital coordination has promoted collaboration and knowledge exchange, while access to real-time data has supported evidence-driven improvements in care practices.

Establishing a national registry for PICUs is a pivotal step toward improving quality, benchmarking outcomes, and informing health policy; however, the process is fraught with complex challenges that require careful navigation. The Kuwait PICU registry captures standardized outcome measures like mortality, discharge status, Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI), and Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI) rates, which can be analyzed both at the national level and at individual institutional levels. By collecting harmonized, high-quality data across all PICUs, the registry provides a platform to compare local performance against national aggregates and internationally reported benchmarks. This enables each hospital to identify areas for improvement, align clinical practices with global standards, and contribute Kuwaiti pediatric critical care data to international registries or collaborative research networks.

One of the foremost obstacles is the inherent heterogeneity of pediatric critical illness, characterized by diverse pathologies and wide variations in disease severity, which necessitate large-scale, multicenter collaboration to achieve meaningful data aggregation and analysis.20 Additionally, data standardization across institutions remains a persistent barrier, as pediatric-specific variables often lack universally accepted definitions, and electronic health record systems differ widely in structure and functionality, complicating interoperability and data harmonization.7,21,22 This challenge was addressed by establishing standardized definitions for all variables, ensuring consistency and reliability of the data entered (Table 4). Ensuring data completeness and accuracy adds further complexity, especially within high-acuity environments where frontline clinicians may lack time or resources to engage in rigorous data entry, making routine audits and feedback mechanisms essential, yet resource-intensive.22,23 Financial and human resource constraints, particularly in lower-resource settings, also pose significant threats to registry sustainability, with limited availability of trained data personnel and informatics support frequently impeding ongoing data collection and system maintenance.24 The registry was initially launched through voluntary efforts, with strong support from the heads of participating units, reflecting the Kuwait PICUs Taskforce Group’s commitment to advancing and standardizing pediatric critical care across the country. As the participating units recognized the positive impact of this collective effort, momentum was sustained, and plans were initiated to explore future funding opportunities aimed at expanding the registry and securing its long-term sustainability. Ethical and regulatory considerations introduce additional layers of complexity, especially data privacy protections and guardianship laws must be carefully addressed through robust governance frameworks. Finally, maintaining long-term institutional engagement remains a formidable challenge; registry success depends not only on initial enthusiasm but also on sustained leadership, continuous funding, and alignment with national pediatric health priorities. Together, these multifaceted barriers highlight the need for strategic planning, stakeholder collaboration, and adaptable infrastructure to ensure the successful implementation and longevity of national PICU registries. Looking forward, planned advancements include the incorporation of patient-reported outcomes and the extension of the registry framework to additional pediatric subspecialties. These initiatives hold significant potential to further elevate the quality of care delivered across the nation’s pediatric services.

One of the key advantages of the registry was its capacity to inform equipment and staffing projections using historical tercile data, as illustrated in the exemplary report (Fig. 3), which details utilization patterns for high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC), non-invasive ventilation (NIV), central venous lines, and intubation. Deeper analysis of the registry can uncover monthly or seasonal trends, supporting more precise forecasting of resource demands. These gains paved the way for broader improvements, including revised clinical guidelines and knowledge sharing between hospitals. The variability in data capture performance across sites likely reflects differences in local workflows, staffing, and data management practices, underscoring the need for targeted quality improvement initiatives such as focused audits and standardized data entry training to enhance data accuracy and reliability across all PICUs. The registry is now fully integrated into national pediatric critical care practice in Kuwait, where it plays a pivotal role in both clinical care delivery and strategic planning.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the analysis is based on retrospectively collected data from the early phase of registry implementation, which may introduce inconsistencies related to documentation practices and variable data-entry experience across sites. Second, completeness was assessed by comparing registry entries with manual admission censuses, a process that relies on the accuracy of local census logs and may not capture all missed cases. Third, the platform currently operates without full real-time integration with hospital information systems, potentially affecting timeliness and workflow efficiency. Additionally, long-term sustainability may be vulnerable in the absence of dedicated external funding to support system maintenance, upgrades, and personnel. Finally, because the registry was developed within a single national health system, generalizability to other regions may be influenced by differences in organizational structures, governance models, and resource availability. Despite these limitations, the findings offer important insights into the practical steps, challenges, and enabling factors involved in establishing a national critical care registry.

Conclusion

The successful implementation and outcomes of the Kuwait PICUs Registry’s demonstrate both the feasibility and transformative potential of a unified national pediatric critical care data system. Through voluntary collaboration, standardized data collection, and strategic leadership, the registry has enabled meaningful insights into clinical practice variation, resource utilization, and system-wide performance. Most importantly, the registry has empowered healthcare providers to enhance care delivery, informed national-level planning, and established a foundation for future expansion into pediatric subspecialties and international research partnerships. These findings underscore the critical role of robust clinical registries in driving evidence-based care and advancing pediatric critical care services on both national and global scales.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Olatunji, G. et al. Challenges and strategies in pediatric critical care: insights from low-resource settings. Glob Pediatr Health https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794x241285964 (2024).

Simon, T. D. et al. Pediatric medical complexity algorithm: a new method to stratify children by medical complexity. Pediatrics 133, e1647–e1654 (2014).

Chee, G., Pielemeier, N., Lion, A. & Connor, C. Why differentiating between health system support and health system strengthening is needed. Int J. Health Plann Manag. 28, 85–94 (2013).

Hoque, D. M. E. et al. Impact of clinical registries on quality of patient care and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 12, e0183667 (2017).

Beane, A., Salluh, J. I. F. & Haniffa, R. What intensive care registries can teach us about outcomes. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 27, 537–543 (2021).

Salluh, J. I. F. et al. National ICU registries as enablers of clinical research and quality improvement. Crit. Care Med. 52, 125–135 (2024).

Hornik, C. P. et al. Creation of a multicenter pediatric inpatient data repository derived from electronic health records. Appl. Clin. Inf. 10, 307–315 (2019).

Roumeliotis, N. et al. Designing a national pediatric critical care database: a Delphi consensus study. Can. J. Anesthesia/J. Can. Anesthésie 70, 1216–1225 (2023).

Stubbs, E., Exley, J., Wittenberg, R. & Mays, N. How to establish and sustain a disease registry: insights from a qualitative study of six disease registries in the UK. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 24, 361 (2024).

Li, E., Clarke, J., Ashrafian, H., Darzi, A. & Neves, A. L. The impact of electronic health record interoperability on safety and quality of care in high-income countries: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 24, e38144 (2022).

Dowling, N. M., Olson, N., Mish, T., Kaprakattu, P. & Gleason, C. A model for the design and implementation of a participant recruitment registry for clinical studies of older adults. Clin. Trials 9, 204–214 (2012).

Vanderhout, S. et al. Ethical and practical considerations related to data sharing when collecting patient-reported outcomes in care-based child health research. Qual. Life Res. 32, 2319–2328 (2023).

Lazem, M. & Sheikhtaheri, A. Barriers and facilitators for disease registry systems: a mixed-method study. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 22, 97 (2022).

Information KPAFC. Statistical Reports. paci. https://stat.paci.gov.kw/englishreports/

Shaikh, F. Quality indicators and improvement measures for pediatric intensive care units. J. Pediatr. Crit. Care 7, 260–270 (2020).

Wani, T. A., Mendoza, A. & Gray, K. Hospital bring-your-own-device security challenges and solutions: systematic review of gray literature. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8, e18175 (2020).

Gui, X. et al. Physician champions’ perspectives and practices on electronic health records implementation: challenges and strategies. JAMIA Open 3, 53–61 (2020).

Pettersen, S., Eide, H. & Berg, A. The role of champions in the implementation of technology in healthcare services: a systematic mixed studies review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 24, 456 (2024).

Dempsey, K. et al. Which strategies support the effective use of clinical practice guidelines and clinical quality registry data to inform health service delivery? A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 11, 237 (2022).

Paul, R. et al. Metric development for the multicenter improving pediatric sepsis outcomes (IPSO) Collaborative. Pediatrics 147 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-017889 (2021).

Shafi, O. et al. Defining electronic health record standards for child health: a state-of-the-art review. Appl Clin. Inf. 15, 55–63 (2024).

Macias, C. G., Remy, K. E. & Barda, A. J. Utilizing big data from electronic health records in pediatric clinical care. Pediatr. Res. 93, 382–389 (2023).

Gaies, M. et al. Data integrity of the pediatric cardiac critical care consortium (PC4) clinical registry. Cardiol. Young. 26, 1090–1096 (2016).

Grant, C. L. et al. Improved documentation following the implementation of a trauma registry: a means of sustainability for trauma registries in low- and middle-income countries. Injury 52, 2672–2676 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We extend our appreciation to the entire registry team for their pivotal role in developing and implementing the PICU registry. We would like to especially acknowledge Ahmed Abdelmoniem, Deyaa Madian, Hayam Yahia, Ibrahim Hikal, Mostafa Galal, Shishir Shetty, Farahat Elsayed, and Waleed Ramadan for their unwavering dedication and continuous support throughout this initiative.

Funding

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Patient consent was not required for this study as all patient data were de-identified and encrypted in accordance with the approval granted by the Kuwait Ministry of Health Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the registry was obtained from our local Institutional Review Board (IRB) in the Ministry of Health (MOH), Kuwait (Approval No. 2594/2024).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aldaithan, A., Al-Hashimi, H., Altammar, F. et al. From fragmentation to integration: the implementation of Kuwait’s nationwide pediatric intensive care units registry. Pediatr Res (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-026-04775-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-026-04775-1