Abstract

This open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant sintilimab combined with anlotinib and chemotherapy, followed by adjuvant sintilimab, for resectable NSCLC. Forty-five patients received anlotinib (10 mg, QD, PO, days 1–14), sintilimab (200 mg, day 1), and platinum-based chemotherapy of each three-week cycle for 3 cycles, followed by surgery within 4–6 weeks. Adjuvant sintilimab (200 mg) was administered every 3 weeks. The primary endpoint was achieving a pathological complete response (pCR). From June 10, 2021 through October 10, 2023, 45 patients were enrolled and composed the intention-to-treat population. Twenty-six patients (57.8%) achieved pCR, and 30 (66.7%) achieved major pathological response (MPR). Forty-one patients underwent surgery. In the per-protocol set (PP set), 63.4% (26/41) achieved pCR, and 73.2% achieved MPR. The median event-free survival was not attained (95% CI, 25.1-NE). During the neoadjuvant treatment phase, grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events were observed in 25 patients (55.6%), while immune-related adverse events were reported in 7 patients (15.6%). We assessed vascular normalization and infiltration of immune-related cells by detecting the expression of relevant cell markers in NSCLC tissues with mIHC. Significant tumor microenvironment changes were observed in pCR patients, including reduced VEGF+ cells and CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells, and increased perivascular CD4+ T cells, CD39+CD8+ T cells, and M1 macrophages. In conclusion, perioperative sintilimab and neoadjuvant anlotinib plus chemotherapy achieved pCR in a notable proportion of patients with resectable NSCLC and were associated with profound changes in the tumour microenvironment (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05400070).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer ranks as the second most common cancer and is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide.1 In China alone, it accounts for 40% of global lung cancer fatalities.2 Approximately 20–25% of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) present with resectable disease at diagnosis.3 Compared to surgery, standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy offers only limited improvements in recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS).4 Key studies, such as the Checkmate-8165 and KEYNOTE-6716 trials, have demonstrated that combining neoadjuvant immunotherapy with concurrent chemotherapy is both effective and safe for resectable NSCLC. Though perioperative immune checkpoint inhibition holds promise for improving response rates and decreasing recurrence in patients with resectable NSCLC,7 the majority of patients with resectable disease fail to achieve a pathological complete response (pCR). In the randomized TD-FOREKNOW trial, patients with resectable stage IIIA or IIIB NSCLC who were treated with camrelizumab and chemotherapy had a pCR rate of 32.6%, compared to an 8.9% pCR rate in those receiving chemotherapy alone.8 In the Checkmate-816 trial, ~24.0% of patients with resectable stage IB–IIIA NSCLC who received neoadjuvant nivolumab in combination with chemotherapy achieved a pCR,5 while in the KEYNOTE-671 trial, 18.1% of resectable stage II–IIIB NSCLC patients achieved a pCR to perioperative pembrolizumab.6

Aberrant oncoangiogenesis is a hallmark of cancer and a key driver of tumour growth and metastasis9 and represents a rational target in NSCLC,10 as demonstrated in the IMpower150 study11 and the TASUKI-52 trial.12 Antiangiogenic therapy can shift the immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment (TME) towards an immune-active state. Nevertheless, neoadjuvant bevacizumab plus chemotherapy failed to improve the rate of pathological downstaging over historical control in patients with resectable stage IB–IIIA nonsquamous NSCLC.13 The findings from trials of neoadjuvant immunotherapy or antiangiogenic therapy plus chemotherapy indicate that either immunotherapy or antiangiogenic therapy alone leaves many patients at risk for relapse and eventual death, while a therapeutic strategy combining the two approaches can lead to a better clinical outcome.14

Sintilimab is a selective, fully human IgG4 anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, approved in China for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC. In the neoadjuvant setting, sintilimab monotherapy led to a major pathological response (MPR) in 15 resectable stage IA–IIIB NSCLC patients (15/37, 41%) and pCR in 6 (6/37, 16%). When added to chemotherapy, neoadjuvant sintilimab attained a MPR rate of 43% (13/30) in resectable stage IIIA NSCLC patients.15 In an interim analysis of a phase 2 trial, neoadjuvant sintilimab plus chemotherapy yielded an MPR of 63% (10/16) and a pCR of 31% (5/16) in patients with resectable stage IIIA/B NSCLC.16

Anlotinib is an antiangiogenic drug and multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets VEGFR1, VEGFR2, VEGFR3, c-KIT, and PDGFR β.17 It is approved in China for treating locally advanced and metastatic NSCLC that has progressed or recurred after at least two lines of systemic chemotherapy.18 Compared with intravenous infusion, multikinase inhibitors provide more convenient oral dosing for currently available antiangiogenic agents. Treatment with anlotinib plus the programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitor TQB2450 increased the progression-free survival (PFS) of pretreatment stage IIIB or IV NSCLC patients with no mutated driver genes by 6 months (total: 8.7 months, 95% confidence interval [CI] 6.1–17.1) vs. TQB2450 2.8 months, 95% CI 1.4–4.7). In a phase 1b study, 16 treatment-naïve patients (16/22, 73%) with unresectable, driver-negative, stage IIIB/C or IV NSCLC showed an objective response to anlotinib plus sintilimab.19 Anlotinib has not yet been studied alone or in combination with other treatments, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, for resectable NSCLC in clinical trials.

This phase 2 trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant sintilimab combined with anlotinib and chemotherapy, followed by adjuvant sintilimab, for the treatment of resectable NSCLC. Additionally, it explored alterations in the TME as potential biomarkers for predicting the response to this combined neoadjuvant immunotherapy and antiangiogenic treatment.

Results

Patient baseline and treatment characteristics

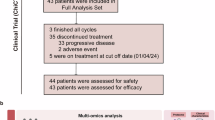

From June 10, 2021 through October 10, 2023, 67 patients underwent screening, 45 of whom, including 41 males and 4 females, were eligible to receive sintilimab plus anlotinib concurrent with platinum-based doublet chemotherapy; these patients composed the intention-to-treat (ITT) population (Supplementary Fig. 1). Among them, 34 (75.6%) had squamous cell carcinoma and 33 (73.3%) had stage III disease (IIIA, n = 15, 33.3%, and IIIB, n = 18, 40.0%). Thirty-seven patients (82.2%) were former or current smokers. The demographics and baseline characteristics of the patients are detailed in Table 1.

In the neoadjuvant treatment period, one patient discontinued treatment due to grade 3 elevated aminotransferases and grade 4 myelosuppression. Three patients declined surgery. In the PP set, 33 of 41 patients (80.5%) completed the prespecified 3 cycles of neoadjuvant treatment, and 8 patients underwent surgery after 2 cycles of treatment. Six patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events (AEs) in the adjuvant treatment period. The patients’ exposure to anlotinib, sintilimab and individual chemotherapeutic drugs is summarized in the Supplementary Materials (specific circumstances of the patients).

Efficacy measures

In the ITT population, pCR and MPR were reported for 26 patients (57.8%, 95% CI 43.3–71.0) and 30 patients (66.7%, 95% CI 52.1–78.6), respectively. Two patients achieved CR, and 30 achieved a partial response (PR). The objective response rate (ORR) was 71.1% (32/45, 95% CI 55.7–83.6) (Fig. 1). Twelve patients had stable disease (SD); the disease control rate (DCR) was 97.8% (44/45, 95% CI 88.2–99.9) (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Table 2). Two patients with squamous cell carcinoma achieved CR, and 24 achieved PR (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Their ORR was 76.5% (26/34, 95% CI 60.0–87.6). Eight of these patients had SD; the DCR was 100.0% (34/34, 95% CI 89.6–100.0). No patients with adenocarcinoma achieved CR, while 5 achieved PR. Their ORR was 50.0% (5/10, 95% CI 23.7–76.3) (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Four of them had SD, and the DCR was 90.0% (9/10, 95% CI 59.6–98.2).

Responses to sintilimab combined with anlotinib and concurrent neoadjuvant chemotherapy were assessed in patients with resectable non-small-cell lung cancer within the intention-to-treat population. Investigators evaluated patients based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST), version 1.1. Each swim lane corresponds to a single patient in the ITT group, with patient characteristics and outcomes indicated by specific color codes. CR complete response, PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease

In the PP set, pCR occurred in 26 patients (26/41, 63.4%, 95% CI 48.1–76.4), and MPR occurred in 30 patients (30/41, 73.2%, 95% CI 58.1–84.3) (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Pathologically downstaged tumours were detected in 87.8% (36/41) of the patients. pCR occurred in 73.3% (22/30, 95% CI 55.6–85.8) of the patients with squamous cell carcinoma (Supplementary Fig. 3c) and 30.0% (3/10, 95% CI 10.8–60.3) of the patients with adenocarcinoma (Supplementary Fig. 3d). One patient with sarcomatoid carcinoma achieved both a PR and a pCR.

Lobectomy was the most common surgical procedure (Supplementary Table 1). Among patients who underwent surgery, 92.7% (38/41) had complete (R0) resection; the others (3/41, 7.3%) had R1 resection (the lymph node of the highest station was metastatic). None of the patients underwent R2 resection or had unresectable tumours. The median postoperative hospital stay was 8 days, with a range of 3–25 days.

As of the data cutoff on December 31, 2023, the median follow-up duration was 22.8 months (IQR 9.9–33.6 months), with a 24-month estimated event-free survival (EFS) rate of 81.5% (95% CI, 64.5–90.9%). The median EFS was not reached (95% CI, 25.1-NE) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 2). A post hoc subgroup analysis revealed no significant differences in EFS among various patient subgroups (Supplementary Table 3). Two patients (4%) were lost to follow-up, and two patients (4%) passed away. The estimated 12-month survival rate was 97.7% (95% CI, 84.6–99.7%). The median OS was not reached (95% CI, NE-NE) (Fig. 2b).

Kaplan–Meier estimates of (a) event-free survival and b overall survival. EFS was defined as the interval from enrolment to the earliest occurrence of local progression resulting in inoperability; unresectable tumour, disease progression or recurrence according to RECIST version 1.1 as assessed by the investigator; or death from any cause. OS was defined as the time from enrollment to death from any cause. Tick marks represent censored data

Safety

All-grade treatment-related AEs (TRAEs), including grade 3 or 4 TRAEs in 25 patients (25/45, 55.6%), occurred in 100.0% (45/45) of patients during the neoadjuvant treatment period. The three most frequent TRAEs (grade 3 or 4) were white blood cell count decrease (5/45, 11.1%), neutrophil count decrease (5/45, 11.1%), and vomiting (4/45, 8.9%) (Table 3). In addition, immune-related AEs (irAEs) occurred in 7 patients (7/45, 15.6%). Two patients developed cavitation-like lesions after anlotinib treatment but did not experience haemoptysis.

In the adjuvant treatment period, irAEs occurred in 14 patients (14/41, 34.1%), including grade 3 irAEs in 7 patients (7/41, 17.1%). Grade 3 adrenal insufficiency and fatigue occurred in 2 patients, respectively (2/41, 4.9%) (Table 3).

According to the Clavien–Dindo classification, 14 patients (14/41, 34.1%) developed postoperative complications. Grade 3 complications, including pleural effusion (6/41, 14.6%), pneumonia (3/41, 7.3%), and pneumothorax (3/41, 7.3%), occurred in 19.5% (8/41) of the patients (Table 3).

Neoadjuvant anlotinib and sintilimab modulate the TME

Dynamic changes in the tumor microenvironment before and after treatment are vital indicators for evaluating the effectiveness of tumor immunotherapy. Therefore, we focused on evaluating vascular normalization and the infiltration of immune cells relevant to immunotherapy using mIHC technology. Specifically, we evaluated vascular normalization by analyzing the count of VEGF+ cells, the ratio of CD31+/NG2+ cells, and the infiltration of perivascular CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, we assessed immune cell infiltration by quantifying several immune cell types involved in the tumor immune response, including Treg cells (CD4+Foxp3+ T cells), M1 macrophages (CD80+CD11c+ cells), M2 macrophages (CD80+CD206+ cells), PD-1+CD8+ cells, and CD39+CD8+ cells.

Since the existence of Tregs in the TME is closely related to the efficacy of immunotherapy,20 we first observed Treg infiltration. CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cell21,22 infiltration decreased significantly after treatment compared to baseline in the pCR group, and there were no significant differences in the non-pCR group (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). CD8+ T cells in the TME are a key cell population in the response to immunotherapy,23 so we further examined this population, and the results showed that CD8+ T-cell infiltration exhibited an overall upward trend in the pCR group from baseline to posttreatment and a downward trend in the non-pCR group, but the difference was not significant (Supplementary Fig. 4c).

VEGF plays a crucial role in tumor angiogenesis and contributes significantly to immunosuppression within the TME.24 In our observations, patients who achieved a pCR after neoadjuvant therapy showed a notable decrease in VEGF+ cells in the TME. Conversely, those who did not achieve pCR exhibited a slight increase in the frequency of VEGF+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). The ratio of cells that are positive for endothelial cell marker CD31 to cells that are positive for pericyte marker neural/glial antigen (NG2) is a key indicator of vascular normalization.25 We found that there was a significant decrease in the CD31+/NG2+ cell ratio in tumour vessels after neoadjuvant treatment compared with baseline (Fig. 3a, b). Patients who achieved pCR experienced a significant decrease in the frequency of CD31+/NG2+ cell ratio from baseline, while patients who failed to achieve pCR experienced no significant change from baseline (Fig. 3c).

Representative images and quantification of multiplex immunohistochemical staining of tumours at baseline and after neoadjuvant treatment (post-NT). a–c Assessment of the expression levels of CD31 (endothelial cells, red) and NG2 (pericytes, green) in the lung cancer microenvironment before and after treatment, along with statistical analysis of the ratio of CD31+ to NG2+. a Representative images of the lung cancer microenvironment showing CD31 and NG2 staining. b Statistical analysis of the CD31+ to NG2+ ratio in baseline and post-neoadjuvant treatment samples (paired samples, n = 14). c Statistical analysis of the CD31+ to NG2+ ratio in baseline and post-neoadjuvant treatment samples within the pCR group (paired samples, n = 11) and the non-pCR group (paired samples, n = 3). d–f Perivascular CD4+ T cell count per μm² of vascular area. CD31 staining (red) represents the vascular area, while CD4 staining (pink) indicates the infiltration of CD4+ T cells. d Representative images of the lung cancer microenvironment showing CD31 and CD4 staining. e Statistical analysis of perivascular CD4+ T cell count per μm2 of vascular area in baseline and post-neoadjuvant treatment samples (paired samples, n = 16). f Statistical analysis of perivascular CD4+ T cell count per μm2 of vascular area in baseline and post-neoadjuvant treatment samples within the pCR group (paired samples, n = 13) and the non-pCR group (paired samples, n = 3). g–i Assessment of the expression levels of CD80 (pink) and CD11c (green) in the lung cancer microenvironment before and after treatment, along with statistical analysis of the infiltration of CD11c+CD80+ M1 macrophage. g Representative images of the lung cancer microenvironment showing CD80 and CD11c staining. h Statistical analysis of the CD11c+CD80+ M1 macrophage in baseline and post-neoadjuvant treatment samples (paired samples, n = 12). i Statistical analysis of the CD11c+CD80+ M1 macrophage in baseline and post-neoadjuvant treatment samples within the pCR group (paired samples, n = 9) and the non-pCR group (paired samples, n = 3). j Representative images of the lung cancer microenvironment showing PD-1 (pink) and CD8 (green) staining. k Statistical analysis of the PD-1+CD8+ T cell in baseline and post-neoadjuvant treatment samples within the pCR group (paired samples, n = 5) and the non-pCR group (paired samples, n = 3). l Representative images of the lung cancer microenvironment showing CD39 (pink) and CD8 (green) staining. m Statistical analysis of the CD39+CD8+ T cell in baseline and post-neoadjuvant treatment samples within the pCR group (paired samples, n = 6) and the non-pCR group (paired samples, n = 3). Data are mean ± SD. a–h Wilcoxon paired t test. No Significance (ns), ns: P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01

Since vascular normalization can promote the recruitment of cell populations relevant to the response to immunotherapy,24,26 we examined vascular peripheral immune cell infiltration in the TME. We observed a significant increase in perivascular CD4+ T cell infiltration post-treatment compared to baseline (Fig. 3d, e). Notably, this increase was significant in the pCR group but not in the non-pCR group (Fig. 3f). There were no significant changes in perivascular CD8+ T cell levels after treatment versus baseline in either group (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b).

We also observed a slight upward trend in the overall frequency of M1 macrophages after neoadjuvant treatment (median: 1.98%) versus baseline (median: 1.74%), although the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 3g, h). Further analysis showed that in the pCR group, the percentage of M1 macrophages increased significantly after neoadjuvant treatment (median: 3.27%) versus baseline (median: 1.36%) (Fig. 3i). In addition, the frequency of M2 macrophages did not significantly change after neoadjuvant treatment compared with baseline in patients in either the pCR or non-pCR group (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b).

We measured the frequency of PD-1+ CD8+ T cells within CD8+ T cells in the TME, as this ratio can predict immunotherapy effectiveness.27 In the pCR group, the PD-1+ CD8+ T cell/CD8+ T cell ratio significantly decreased after treatment (4.97%) compared to baseline (9.15%). In contrast, the ratio increased in the non-pCR group after treatment (32.12%) from baseline (4.22%) (Fig. 3j, k).

Immune checkpoint blockade increases the frequency of intratumoral CD39+ CD8+ T cells, and CD39 may serve as a surrogate marker of tumour-reactive CD8+ T cells in human lung cancer.28 We found that the frequency of CD39+ CD8+ T cells was significantly greater after neoadjuvant therapy than at baseline in patients who achieved pCR, while no significant differences were observed in the non-pCR group (Fig. 3l, m).

By analysing the baseline cell subtypes, including the frequencies of CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells (Supplementary Fig. 8a), VEGF+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 8b), CD39+CD8+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 8c), the ratios of PD-1+CD8+ T cells/CD8+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 8d), M1 macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 8e) and M2 macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 8f), we found that there were no correlations between patient outcomes during neoadjuvant therapy and these cell subtypes. These findings may need validation in larger studies with extended follow-up to statistically correlate survival outcomes with baseline biomarkers.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of perioperative immunotherapy and neoadjuvant antiangiogenic therapy plus SOC chemotherapy for resectable NSCLC. In this phase 2 trial, perioperative immune therapy with sintilimab and neoadjuvant antiangiogenic therapy with anlotinib plus SOC achieved a pCR rate of 57.8% (95% CI 43.3–71.0) in the ITT population and 63.4% in the PP set and a 12-month EFS rate of 97.7% (95% CI 84.6–99.7) in patients with resectable stage IIA-IIIB NSCLC. Furthermore, 73.2% (95% CI 58.1–84.3) of the patients achieved MPR, and the tumours were successfully downstaged in 87.8% of the patients in the PP set. In addition, no safety signals emerged during the trial. There was also no notable increase in the incidence of surgical complications. The results are highly promising, as they demonstrate the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of this combinatorial approach and supporting further exploration of therapeutic regimens for resectable NSCLC.

Although they have not been directly compared with immune therapy plus SOC chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting, the proportion of resectable stage IIA-IIIB NSCLC patients who achieved pCR with anlotinib and sintilimab plus SOC chemotherapy (63.4%, 95% CI 48.1–76.4) was higher than that with neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy for resectable stage IB–IIIA NSCLC patients in the Checkmate-816 trial (24.0%, 95% CI, 18.0–31.0),5 perioperative pembrolizumab for resectable stage II–IIIB NSCLC patients in the KEYNOTE-671 trial (18.1%, 95% CI, 14.5–22.3),6 and neoadjuvant sintilimab plus chemotherapy in resectable stage IIIA/B NSCLC patients (31%, 95% CI, 20.4–45.8).16 Our results also compare favourably with those of the AEGEAN trial and the Neotorch study. In the AEGEAN trial, the addition of perioperative durvalumab therapy to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery led to a pCR rate of 17.2% (4.3% for placebo; difference, 13.0%; 95% CI, 8.7–17.6) among patients with resectable stage II or III NSCLC.29 In the Neotorch study, which was conducted in China, perioperative toripalimab led to significantly more pCR compared with placebo (24.8%, 95% CI, 19.0–31.3 vs. 1.0%, 95% CI, 0.1–3.5) in patients with stage III NSCLC.30 In addition, the proportion of resectable stage IIA-IIIB NSCLC patients who achieved pCR with anlotinib and sintilimab plus SOC chemotherapy (63.4%, 95% CI 48.1–76.4) was higher than that of patients who achieved pCR with neoadjuvant camrelizumab, an anti-PD-1 antibody and apatinib, an antiangiogenic agent, for resectable stage IIA to IIIB NSCLC patients (15/65, 23%, 95% CI 14–35).31 Furthermore, the rate of pathological downstaging reached 87.8% (36/41, 95% CI 74.5–94.7) in our patients. This finding compares favourably to that of neoadjuvant bevacizumab plus chemotherapy for patients with resectable stage IB–IIIA nonsquamous NSCLC13 (38%, 95% CI 25–53). Notably, all of the above comparisons were indirect, so clinical trials conducting direct comparisons of different regimens would be more reliable.

pCR and MPR have been associated with better survival outcomes among patients with resectable NSCLC receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy32,33 and among patients receiving neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy. The median EFS was not reached, and the 12-month OS was 97.7% (95% CI 84.6–99.7). The high rate of pCR and MPR and the low number of events at 12 months under perioperative sintilimab and neoadjuvant anlotinib for resectable lung tumours are encouraging. In the AEGEAN trial, perioperative durvalumab therapy achieved an EFS of 73.4% (95% CI, 67.9–78.1) at 12 months (64.5% for placebo, 95% CI, 58.8–69.6) among patients with resectable stage II or III NSCLC.29 In the Neotorch study, perioperative toripalimab led to significant improvement in EFS (HR = 0.40, 95% CI 0.277–0.565) in patients with stage III NSCLC compared with placebo.30 As the data of the current trial are still not mature, it remains to be seen whether improvements in the rate of pCR and the MPR can be translated into survival benefits for resectable NSCLC patients. The results suggest an overall benefit of neoadjuvant antiangiogenic therapy combined with perioperative immunotherapy plus chemotherapy, and the perioperative regimen appears to confer a benefit that is at least similar to, if not greater than, that of neoadjuvant or perioperative immunotherapy alone. Nevertheless, future trials directly comparing neoadjuvant antiangiogenic therapy plus perioperative immunotherapy and perioperative immunotherapy alone are needed.

Compared to chemoimmunotherapy regimens (such as those tested in the KEYNOTE-671 and Checkmate-816 trials), one with an additional antiangiogenic drug, anlotinib, was tested in our study. This antiangiogenic agent has been reported to have a role in promoting vascular normalization.34,35 In our study, by observing CD31+/NG2+ cell ratios, infiltration of M1 cells (especially in the pCR group), and perivascular CD4+ T cells (especially in the pCR group), we found that the normalization of vessels was significantly increased in patients treated with this regimen. Considering that normalized vessels can improve the perfusion of blood within the tumour tissue, which in turn brings more oxygen, nutrients, and infiltration of antitumour immune cells to the tumour tissue,24,36 and that all of the above factors favour the success of immunotherapy,37,38 we believe that the increase in the rate of pCR and MPR in our study is most likely due to the addition of the extra anti-angiogenic drug anilotinib.

In the current trial, the patients had a safety profile consistent with that of individual drugs, and no new safety concerns emerged. The majority of TRAEs were associated with chemotherapy. Only two patients developed cavity formation, and complications like haemoptysis were not observed throughout the treatment. Grade 3 or 4 TRAEs were manageable, and no grade 5 TRAEs were reported. Thus, this therapeutic regimen exhibits both safety and significant improvements in efficacy.

Our study has several limitations. Given the small number of patients enrolled, this study had limited statistical power. As a single-arm study, there was no control arm for comparison, unlike in the AEGAEN trial. The trial design did not allow direct analysis of the relative contributions of perioperative sintilimab and neoadjuvant anlotinib. The postoperative follow-up was also short, preventing analysis of long-term outcomes to determine the best predictive biomarkers of response and their correlation with survival outcomes. An improved understanding of these questions would allow us to advance cancer antiangiogenic agents and immunotherapies. In addition, the trial included only three patients with EGFR mutations and excluded patients with ALK translocations, so the study findings might not offer any insights into patients with EGFR mutations or ALK translocations in their tumours, who are known to have a limited response to immunotherapy.39

In conclusion, we demonstrate the promising antitumour effects of perioperative immunotherapy with neoadjuvant antiangiogenic therapy in patients with resectable NSCLC. Such a combinatorial therapeutic approach followed by surgical resection and adjuvant sintilimab therapy could offer a new treatment option for patients with resectable NSCLC and should be further explored in advanced trials.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial took place at the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Tangdu Hospital, Air Force Medical University, Xian, China, and the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Third Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China. Eligible participants were adults aged 18–75 with histologically confirmed resectable NSCLC (stage IIA-IIIB per AJCC 8th edition). Patients needed to have adequate organ function, an ECOG performance status score of 0 or 1, and at least one measurable lesion according to RECIST version 1.1.40 Patients should be deemed to have adequate lung function for resection. Pretreatment tumour tissues should be available for immunohistochemical assessment of PD-L1 expression with the use of the SP263 PD-L1 immunohistochemistry (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA). All patients with lung adenocarcinoma underwent testing for genetic alterations, and patients with known ALK translocations and who were ROS1 fusion-positive were excluded. The patients could have received no prior chemotherapy or any antitumour therapy, including anti-PD-1 or PD-L1, anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) treatment, and antiangiogenic therapy. Other key exclusion criteria were active infection requiring systemic therapy, uncontrolled hypertension, active diverticulitis, abdominal abscess, fistulation or perforation, gastrointestinal obstruction, or ongoing haemoptysis (>50 mL/day). The full eligibility criteria are detailed in the study protocol. The study protocol received approval from the Ethics Committees of Tangdu Hospital and the Third Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. It adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and ICH-GCP guidelines. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment, and the study followed CONSORT reporting guidelines. The trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov under NCT05400070.

Treatments

Ten milligrams of anlotinib (Chia Tai Tianqing Pharmaceutical Group Co.) was given orally once on days 1 to 14, and 200 mg of sintilimab (Innovent [Suzhou] Biopharmaceutical Co. Ltd., China) was given intravenously once per three-week cycle on day 1 for a total of three cycles. The patients also received concurrent SOC neoadjuvant platinum-based doublet chemotherapy. Surgery was performed according to local standards within 4–6 weeks of the final dose of neoadjuvant sintilimab and anlotinib plus chemotherapy. The patients were given 200 mg sintilimab intravenously once every 3 weeks for up to one year no later than 6 weeks following surgery. Anlotinib was discontinued if patients developed haemoptysis. For other grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), anlotinib was reduced to 8 mg, and the dose of chemotherapy was reduced by 25.0% of the last dose. Dose modification of sintilimab was prohibited. Patients experiencing intolerable adverse events that led to a delay or discontinuation of one drug continued treatment with the remaining study drug. Treatment continued until intolerable toxicity occurred or consent was withdrawn. Those who developed progressive disease were permitted to undergo surgery or receive SOC-CRT at the investigator’s discretion.

Assessment

Patients underwent radiological evaluations by investigators according to RECIST version 1.1 at baseline, after two cycles of neoadjuvant therapy, prior to surgical resection, and every four cycles during adjuvant therapy until disease progression, intolerable toxicity, death, or withdrawal of consent. Complete and partial responses were confirmed radiologically at least 4 weeks later, while stable disease was confirmed at least 8 weeks after the initial assessment. The ORR was defined as the proportion of patients achieving either a complete or partial response. Patients were followed up by visits or phone calls every 12 weeks to determine survival status.

For pathological assessments, primary lung tumors and lymph node specimens were staged using the AJCC criteria (8th edition). Residual viable tumor percentage in primary tumors was determined from routine hematoxylin and eosin-stained specimens.32,33 Tumors with ≤10% viable cells were classified as having MPR, while those with no residual tumor cells (ypT0N0M0) were classified as having pCR. Pathological downstaging was defined as a reduction in ypTNM stage post-treatment, with no new lesions or progression of existing lesions.

Safety assessments

AEs, including serious AEs (SAEs) and AEs of special interest (AESIs), and laboratory abnormalities were evaluated throughout the treatment period and 30 days after the final dose (up to 90 days for SAEs in the absence of new antitumour therapy) using the Common Toxicity Standards of the National Cancer Institute (NCI CTCAE) version 5.0. The AESIs consisted of immune-related AEs (irAEs), mainly immune-related pneumonitis, myocarditis, and endocrine diseases, and antiangiogenic treatment-related AEs, mainly hypertension, bleeding, and proteinuria.

Postoperative complications were evaluated using the Clavien–Dindo Classification of Surgical Complications. We decided that a treatment was not safe if any grade 5 adverse events occurred.

End points

The primary end point was pCR. The secondary end points included MPR and EFS. EFS was defined as the interval from enrolment to the earliest occurrence of local progression resulting in inoperability; unresectable tumour, disease progression or recurrence according to RECIST version 1.1 as assessed by the investigator; or death from any cause. OS was defined as the time from enrolment to death from any cause.

Biomarkers

We utilized CD31+ cells to represent endothelial cells, NG2+ cells to represent pericytes and the CD31+/NG2+ cell ratio to reflect vascular normalization.25 We calculated the relative CD31+ area in each image, defined as the CD31+ area divided by the total imaged area. The numbers of CD8+ or CD4+ T cells within a 100 μm radius from a CD31+ structure were calculated to represent perivascular T cells.41 We defined Foxp3+CD4+ T cells as Treg cells,21,22 CD11c+CD80+ cells as M1 macrophages, and CD80+CD206+ cells as M2 macrophages.42 We also calculated the number of VEGF+ cells,43 PD-1+CD8+ cells,27 and CD39+CD8+ cells.44

Multiplex immunohistochemical

The paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. After antigen repair, the slides were sealed with hydrogen peroxide and blocked with 10% serum. Subsequently, the slides were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight and incubated with different fluorophore labeled secondary antibodies and the corresponding TSA the next day. After nuclei restained with DAPI, quenching tissue autofluorescence and sealing tablets, panoramic scans of the slides were performed (Nikon Eclipse C1, Pannoramic MIDI). Antibodies against the following proteins were used for the study: CD31 (GB11063-1), CD4 (ab133616), CD8 (GB12068), FOXP3 (GB112325), CD80 (GB114055), CD11c (GB11059), CD206 (24595T), CD39 (GB111582), PD-1 (GB12338), NG2 (GB111915).

Quantification of staining data

The panoramic scans images of slides were acquired as described above. The Indica Labs-HighPlex module of Halo software was used to calculate the number of single-positive cells and double-positive cells in the target area of each section (servicebio Technology CO., LTD, Wuhan), such as VEGF+ cells, CD4+Foxp3+ double-positive cells. The Indica Labs-Area Quantification module of Halo software was used to quantify the area of positive cells (servicebio Technology CO., LTD, Wuhan). For example, CD31+ areas was calculated as mentioned above and CD4+ or CD8+ cells within a 100 μm radius from the CD31+ area were calculated with the Spatial Analysis module and Indica Labs-HighPlex module of Halo software (servicebio Technology CO., LTD, Wuhan). For each CD31+ segment, numbers of CD8+ or CD4+ T cells within the defined area were normalized by the area of the CD31+ segment.

Statistical analysis

The sample size calculation used Simon’s two-stage maximum value design. Based on the Checkmate-816 trial,5 the minimum pCR rate was set at 25%, and the expected pCR rate was 45%. Assuming a type I error rate (α) of 0.05 and a type II error rate (β) of 80%, a sample size of 41 patients was needed. Seventeen patients were enrolled in stage 1. If more than five patients achieved pCR, the trial proceeded to stage 2; otherwise, the trial was terminated.

All the statistical analyses were prespecified and were conducted using SAS version 9.4. The study followed the ITT principle, and efficacy analyses were based on the ITT population, which included all the enrolled patients. The PP set included all patients who received surgery and had at least one after treatment radiological evaluation with no major protocol violations. Patients were censored at the final follow-up visit if they did not have an event. EFS and OS were calculated utilizing the Kaplan–Meier method. The safety set comprised all patients who received at least one dose of sintilimab or anlotinib in combination with chemotherapy during the neoadjuvant treatment phase, as well as those who received at least one dose of sintilimab during this period. Safety data were mainly analyzed through descriptive statistics.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study could be available for scientific purpose from the corresponding author (yanxiaolong@fmmu.edu.cn) 24 months after study completion.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Cao, W. et al. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: a secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chinese. Med. J. 134, 783–791 (2021).

Liang, Y. & Wakelee, H. A. Adjuvant chemotherapy of completely resected early stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2, 403–410 (2013).

Chaft, J. E. et al. Preoperative and postoperative systemic therapy for operable non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 546–555 (2022).

Forde, P. M. et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 386, 1973–1985 (2022).

Wakelee, H. et al. Perioperative pembrolizumab for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 389, 491–503 (2023).

Desai, A. P. et al. Perioperative immune checkpoint inhibition in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: a review. JAMA Oncol. 9, 135–142 (2023).

Lei, J. et al. Neoadjuvant camrelizumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy vs chemotherapy alone for Chinese patients with resectable stage IIIA or IIIB (T3N2) non-small cell lung cancer: the TD-FOREKNOW randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 9, 1348–1355 (2023).

Carmeliet, P. & Jain, R. K. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature 407, 249–257 (2000).

Crinò, L. & Metro, G. Therapeutic options targeting angiogenesis in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur. Respir. Rev. 23, 79–91 (2014).

Socinski, M. A. et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. New Engl. J. Med. 378, 2288–2301 (2018).

Sugawara, S. et al. Nivolumab with carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab for first-line treatment of advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 32, 1137–1147 (2021).

Chaft, J. E. et al. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant bevacizumab plus chemotherapy and adjuvant bevacizumab in patients with resectable nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancers. J. Thorac. Oncol. 8, 1084–1090 (2013).

Lee, W. S. et al. Combination of anti-angiogenic therapy and immune checkpoint blockade normalizes vascular-immune crosstalk to potentiate cancer immunity. Exp. Mol. Med. 52, 1475–1485 (2020).

Zhang, P. et al. Neoadjuvant sintilimab and chemotherapy for resectable stage IIIA non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 114, 949–958 (2022).

Sun, C. et al. Interim analysis of the efficiency and safety of neoadjuvant PD-1 inhibitor (sintilimab) combined with chemotherapy (nab-paclitaxel and carboplatin) in potentially resectable stage IIIA/IIIB non-small cell lung cancer: a single-arm, phase 2 trial. J. Cancer Res. Clin. 149, 819–831 (2022).

Shen, G. et al. Anlotinib: a novel multi-targeting tyrosine kinase inhibitor in clinical development. J. Hematol. Oncol. 11, 120 (2018).

Syed, Y. Y. Anlotinib: first global approval. Drugs 78, 1057–1062 (2018).

Chu, T. et al. Phase 1b study of sintilimab plus anlotinib as first-line therapy in patients with advanced NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16, 643–652 (2021).

Togashi, Y. et al. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunosuppression—implications for anticancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 16, 356–371 (2019).

Saito, T. et al. Two FOXP3(+)CD4(+) T cell subpopulations distinctly control the prognosis of colorectal cancers. Nat. Med. 22, 679–684 (2016).

Savage, P. A., Klawon, D. E. J. & Miller, C. H. Regulatory T cell development. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 38, 421–453 (2020).

Philip, M. & Schietinger, A. CD8(+) T cell differentiation and dysfunction in cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 209–223 (2022).

Fukumura, D., Kloepper, J., Amoozgar, Z., Duda, D. G. & Jain, R. K. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 15, 325–340 (2018).

Tian, L. et al. Mutual regulation of tumour vessel normalization and immunostimulatory reprogramming. Nature 544, 250–254 (2017).

Li, Q. et al. Low-dose anti-angiogenic therapy sensitizes breast cancer to PD-1 blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 1712–1724 (2020).

Kumagai, S. et al. The PD-1 expression balance between effector and regulatory T cells predicts the clinical efficacy of PD-1 blockade therapies. Nat. Immunol. 21, 1346–1358 (2020).

Chow, A. et al. The ectonucleotidase CD39 identifies tumor-reactive CD8(+) T cells predictive of immune checkpoint blockade efficacy in human lung cancer. Immunity 56, 93–106.e106 (2023).

Heymach, J. V. et al. Perioperative durvalumab for resectable non-small-cell lung cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 389, 1672–1684 (2023).

Lu, S. et al. Perioperative toripalimab+ platinum-doublet chemotherapy vs chemotherapy in resectable stage II/III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): interim event-free survival (EFS) analysis of the phase III Neotorch study. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 41, 8501 (2023).

Zhao, J. et al. Efficacy, safety, and biomarker analysis of neoadjuvant camrelizumab and apatinib in patients with resectable NSCLC: a phase 2 clinical trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 18, 780–791 (2023).

Hellmann, M. D. et al. Pathological response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in resectable non-small-cell lung cancers: proposal for the use of major pathological response as a surrogate endpoint. Lancet Oncol. 15, e42–e50 (2014).

Pataer, A. et al. Histopathologic response criteria predict survival of patients with resected lung cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 7, 825–832 (2012).

Augustin, H. G. & Koh, G. Y. Antiangiogenesis: vessel regression, vessel normalization, or both? Cancer Res. 82, 15–17 (2022).

Patel, S. A. et al. Molecular mechanisms and future implications of VEGF/VEGFR in cancer therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 30–39 (2023).

Cao, Y., Langer, R. & Ferrara, N. Targeting angiogenesis in oncology, ophthalmology and beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 22, 476–495 (2023).

Su, Y. et al. Anlotinib induces a T cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment by facilitating vessel normalization and enhances the efficacy of PD-1 checkpoint blockade in neuroblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 793–809 (2022).

Shigeta, K. et al. Dual programmed death receptor-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 blockade promotes vascular normalization and enhances antitumor immune responses in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 71, 1247–1261 (2020).

Calles, A. et al. Checkpoint blockade in lung cancer with driver mutation: choose the road wisely. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 40, 372–384 (2020).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–247 (2009).

Schmittnaegel, M. et al. Dual angiopoietin-2 and VEGFA inhibition elicits antitumor immunity that is enhanced by PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaak9670 (2017).

Cossarizza, A. et al. Guidelines for the use of flow cytometry and cell sorting in immunological studies (third edition). Eur. J. Immunol. 51, 2708–3145 (2021).

Dai, M. et al. Targeting regulation of VEGF by BPTF in non-small cell lung cancer and its potential clinical significance. Eur. J. Med. Res. 27, 299 (2022).

Yeong, J. et al. Intratumoral CD39+CD8+ T cells predict response to programmed cell death protein-1 or programmed death ligand-1 blockade in patients with NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16, 1349–1358 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82173252) and the Miaozi Talent Fund of Tangdu Hospital, Air Force Medical University. We also extend our gratitude to Dr. Wenwen Wang from the Department of Statistics at Air Force Medical University for her valuable guidance and advice on the statistical methods used in this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaolong Yan, Hongtao Duan, Tianhu Wang and Yuan Gao: conception and design; Tianhu Wang and Tao Jiang: administrative support; Hongtao Duan and Changjian Shao: provision of study materials or patients; Hongtao Duan, Changjian Shao, Zhilin Luo and Liping Tong: collection and assembly of data; manuscript writing: all authors; final approval of manuscript: all authors; all authors have read and approved the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol received approval from the Ethics Committees of Tangdu Hospital and the Third Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication and use of any accompanying images. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal upon request.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duan, H., Shao, C., Luo, Z. et al. Perioperative sintilimab and neoadjuvant anlotinib plus chemotherapy for resectable non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial (TD-NeoFOUR trial). Sig Transduct Target Ther 9, 296 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-024-01992-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-024-01992-0

This article is cited by

-

Advances in molecular pathology and therapy of non-small cell lung cancer

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2025)