Abstract

Study design

Retrospective cohort study.

Objectives

To examine the prevalence of polypharmacy for individuals with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction (NTSCD) following inpatient rehabilitation and to determine associated risk factors.

Setting

Ontario, Canada.

Methods

Administrative data housed at ICES, Toronto, Ontario were used. Between 2004 and 2015, we investigated prescription medications dispensed over a 1-year period for persons following an NTSCD-related inpatient rehabilitation admission. Descriptive and analytical statistics were conducted. Using a robust Poisson multivariable regression model, relative risks related to polypharmacy (ten or more drug classes) were calculated. Main independent variables were sex, age, income quintile, and continuity of care with outpatient physician visits.

Results

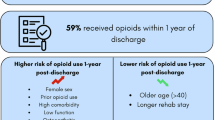

We identified 3468 persons with NTSCD during the observation window. The mean number of drug classes taken post-inpatient rehabilitation was 11.7 (SD = 6.0), with 4.0 different prescribers (SD = 2.5) and 1.8 unique pharmacies (SD = 1.0). Significant predictors for post-discharge polypharmacy were: being female, lower income, higher comorbidities prior to admission, lower Functional Independence Measure at discharge, previous number of medication classes dispensed in year prior to admission, and lower continuity of care with outpatient physician visits. The most common drugs dispensed post-inpatient rehabilitation were antihypertensives (70.0%), laxatives (61.6%), opioids (59.5%), and antibiotics (57.8%).

Conclusion

Similar to previous research with traumatic spinal cord injury, our results indicate that polypharmacy is prevalent among persons with NTSCD. Additional research examining medication therapy management for NTSCD is suggested.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

Data availability

The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While data sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet prespecified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS.

References

Savic G, DeVivo MJ, Frankel HL, Jamous MA, Soni BM, Charlifue S. Long-term survival after traumatic spinal cord injury: a 70-year British study. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:651–8.

Rivers CS, Fallah N, Noonan VK, Whitehurst DG, Schwartz CE, Finkelstein JA, et al. Health conditions: effect on function, health-related quality of life, and life satisfaction after traumatic spinal cord injury. A prospective observational registry cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:443–51.

Adriaansen JJ, Ruijs LE, van Koppenhagen CF, van Asbeck FW, Snoek GJ, van Kuppevelt D, et al. Secondary health conditions and quality of life in persons living with spinal cord injury for at least ten years. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48:853–60.

Cadel L, C. Everall A, Hitzig SL, Packer TL, Patel T, Lofters A et al. Spinal cord injury and polypharmacy: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2019: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1610085.

Duerden M, Avery T, Payne R. Polypharmacy and medicines optimizations: making it safe and sound. 11–13 Cavendish Square London W1G 0AN: The King’s Fund; 2013. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/polypharmacy-and-medicines-optimisation-kingsfund-nov13.pdf. Accessed 16 Jun 2016.

Kitzman P, Cecil D, Kolpek JH. The risks of polypharmacy following spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017;40:147–53.

New PW, Cripps RA, Lee BBonne. Global maps of non-traumatic spinal cord injury epidemiology: towards a living data repository. Spinal Cord. 2014;52:97–109.

Morgan SG, Weymann D, Pratt B, Smolina K, Gladstone EJ, Raymond C, et al. Sex differences in the risk of receiving potentially inappropriate prescriptions among older adults. Age Ageing. 2016;45:535–42.

Jaglal SB, Munce SE, Guilcher SJ, Couris CM, Fung K, Craven BC, et al. Health system factors associated with rehospitalizations after traumatic spinal cord injury: a population-based study. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:604–9.

Guilcher SJT, Munce SEP, Couris CM, Fung K, Craven BC, Verrier M, et al. Health care utilization in non-traumatic and traumatic spinal cord injury: a population-based study. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:45–50.

Guilcher SJT, Hogan ME, Calzavara A, Hitzig SL, Patel T, Packer T, et al. Prescription drug claims following a traumatic spinal cord injury for older adults: a retrospective population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:1059–68.

Fincke BG, Snyder K, Cantillon C, Gaehde S, Standring P, Fiore L, et al. Three complementary definitions of polypharmacy: methods, application and comparison of findings in a large prescription database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:121–8.

World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Anatomical therapeutic chemical code classification index with defined daily doses. http://www.whocc.no/atcddd/.

Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. Continuity of care (Ambulatory): glossary definition. 2011. http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/viewDefinition.php?definitionID=102475.

Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Cicutto L, To T. Identifying patients with physician-diagnosed asthma in health administrative databases. Can Respir J. 2009;16:183–8.

Schultz SE, Rothwell DM, Chen Z, Tu K. Identifying cases of congestive heart failure from administrative data: a validation study using primary care patient records. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2013;33:160–6.

Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Cicutto L, To T. Identifying individuals with physcian diagnosed COPD in health administrative databases. COPD. 2009;6:388–94.

Tu K, Campbell NR, Chen ZL, Cauch-Dudek KJ, McAlister FA. Accuracy of administrative databases in identifying patients with hypertension. Open Med. 2007;1:e18–26.

Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, Bica A. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:512–6.

Widdifield J, Bombardier C, Bernatsky S, Paterson JM, Green D, Young J, et al. An administrative data validation study of the accuracy of algorithms for identifying rheumatoid arthritis: the influence of the reference standard on algorithm performance. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:216.

Jaakkimainen RL, Bronskill SE, Tierney MC, Herrmann N, Green D, Young J, et al. Identification of physician-diagnosed alzheimerʼs disease and related dementias in population-based administrative data: a validation study using family physiciansʼ electronic medical records. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54:337–49.

Koné Pefoyo AJ, Bronskill SE, Gruneir A, Calzavara A, Thavorn K, Petrosyan Y, et al. The increasing burden and complexity of multimorbidity. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:415.

Austin PC, van Walraven C, Wodchis WP, Newman A, Anderson GM. Using the Johns Hopkins Aggregated Diagnosis Groups (ADGs) to predict mortality in a general adult population cohort in Ontario, Canada. Med. Care. 2011;49:932–9.

Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Linacre JM, Heinemann AW, Wright BD. Performance profiles of the functional independence measure. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;72:84–9.

Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–6.

The Canadian Institute for Health Information. Drug use among seniors on public drug programs in Canada, 2016. 2018. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/drug-use-among-seniors-2016-en-web.pdf.

Hand BN, Krause JS, Simpson KN. Polypharmacy and adverse drug events among propensity score matched privately insured persons with and without spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:591–7.

Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:304–14.

Grenard JL, et al. Depression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1175–82.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are those of the author, and not necessarily those of the Canadian Institute for Health Information. The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred.

Funding

This project was funded by a Connaught New Investigator Award (University of Toronto), and the Craig H. Neilsen Psychosocial Research Pilot grant (PSR2-17, grant #441259). SJTG is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Embedded Clinician Scientist Salary Award on Transitions in Care working with Ontario Health (Quality; formerly Health Quality Ontario). AKL is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award, as a Clinician Scientist at the University of Toronto Department of Family and Community Medicine, and as the Chair in Implementation Science at the Peter Gilgan Centre for Women’s Cancers at Women’s College Hospital in partnership with the Canadian Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SJTG conceptualized the study. SJTG, SLH, TP, TaP, and AKL obtained acquisition of study funding and designing the study. SJTG, M-EH, DMC, and AJC, prepared, coordinated, and guided the data analyses and interpretations. DMC and AJC analyzed the data. All authors assisted with overall interpretation and contextualization. SJTG, M-EH and QG assisted with the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and approved manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The use of data in this project was authorized under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which does not require review by a Research Ethics Board. However, we received Research Ethics Board approval from the University of Toronto (#34063).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guilcher, S.J.T., Hogan, ME., McCormack, D. et al. Prescription medications dispensed following a nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction: a retrospective population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Spinal Cord 59, 132–140 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0511-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0511-x

This article is cited by

-

Prevalence of prescribed opioid claims among persons with non-traumatic spinal cord dysfunction in Ontario, Canada: a population-based retrospective cohort study

Spinal Cord (2025)

-

Self-reported benzodiazepine use among adults with chronic spinal cord injury in the southeastern USA: associations with demographic, injury, and opioid use characteristics

Spinal Cord (2024)

-

Examining the impact of COVID-19 on health care utilization among persons with chronic spinal cord injury/dysfunction: a population study

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

The Relationship of Continuity of Care, Polypharmacy and Medication Appropriateness: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies

Drugs & Aging (2023)

-

RETRACTED ARTICLE: Prevalence of prescribed opioid claims among persons with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction in Ontario, Canada: a population-based retrospective cohort study

Spinal Cord (2021)