Abstract

Study Design

Narrative review.

Objectives

Vascular autoregulation in the central nervous system (CNS) maintains appropriate perfusion in the context of changing blood pressure. Impaired autoregulation in various diseases often contributes to their pathophysiology. While this mechanism is well characterized in the brain, it remains understudied in the spinal cord, limiting evidence-based blood pressure management in spinal cord pathology. In this review, we summarize the current understanding of spinal cord autoregulation, highlight advancements in cerebral autoregulation, and offer a framework for its clinical application in spinal cord care.

Methods

A literature search was conducted comparing preclinical evidence of spinal cord autoregulation with current clinical practices in the brain.

Results

Although autoregulation has been recognized in the spinal cord, it has been mostly measured in animals, and its clinical impact has been limited. In contrast, cerebral autoregulation has influenced patient care through continuous monitoring of dynamic autoregulation and clinical trials using personalized blood pressure targets. These innovations require measurement of blood flow or a surrogate, which is performed infrequently in the cord. Furthermore, confounding variables, such as arterial CO2 levels, temperature, and pharmacology, must be tightly controlled, as they can affect blood flow and thus interfere with autoregulation measurements.

Conclusions

Spinal cord autoregulation is an essential variable in neurology and neurosurgery. A better understanding of this process could improve outcomes in various conditions, including traumatic injury, ischemic injury, and other spinal diseases. As spinal cord blood flow measurement technologies improve, there is a growing opportunity to apply autoregulation to direct patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the central nervous system (CNS), maintaining equilibrium consists of added challenges shared with the rest of the body and unique challenges introduced by the fixed volume of the skull and spinal column. This poses a problem in many CNS pathologies, due to the phenomenon of secondary injury. This usually occurs after an initial primary injury, which causes direct neuronal damage. The initial damage is followed by a secondary phase of altered perfusion and inflammation, leading to hypoxia, edema, and hemorrhage [1]. Although the primary phase is usually clinically irreversible, the secondary phase of injury offers an area for mitigation where improved standards of care can directly impact patient outcomes.

In the spine, the phenomenon of secondary injury is important in multiple pathologies, most notably traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) and ischemic injury from aortic cross-clamping. Although this is similar to the secondary injury phenomenon observed in the brain, it is not necessarily identical. One of the ways secondary injury may differ in the spine is through vascular autoregulation.

Autoregulation of blood flow in the CNS is an essential mechanism for maintaining consistent perfusion in the face of changes in arterial pressure. The current knowledge base in cerebral autoregulation has been extensively studied. For example, the Lassen curve of static autoregulation [2], which describes how blood flow at equilibrium remains constant under varying mean arterial pressure (MAP), is an essential principle that drives clinician judgment in neurocritical care. Beyond this, newer developments in dynamic autoregulation, which explore vascular responses under changing MAP, continue to improve our knowledge in the field. In the brain, impairment of static and dynamic autoregulation has proven to have significant impacts on secondary injury in pathologies such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) [3,4,5,6], stroke [7], and subarachnoid hemorrhage [8, 9].

Spinal cord vascular autoregulation has been explored less than cerebral, although, as covered in this review, there is evidence of its essential role in spinal pathologies. As a result, there is less research guiding the diagnosis and management of secondary injury in the spine. In the brain, there are now multiple clinical trials incorporating autoregulation principles in the treatment of TBI [10,11,12]. In contrast, in the spine, we still rely on empiric and less-studied MAP thresholds [13]. As a result, there are significant parallels we can derive from strategies used in brain pathology, with the caveat that there may be significant and unappreciated differences between brain and spine.

The relative lack of dedicated research in the spine could be due to several factors, including the depth of the spinal cord, resulting in increased difficulty in perfusion imaging, limitations in invasive monitoring, complicated interpretation of spinal cord blood flow, and relative sparsity of spinal disease compared to the brain. For example, the world incidence of TBI was found to be ~30-fold higher than SCI (27.16 million, vs 0.91 million) [14]. However, the prevalence of TBI was only twice that of SCI, indicating that proportionately more patients are living with the consequences of substandard secondary injury treatment. As a result, a separate investigation into spinal cord vascular autoregulation is necessary for us to optimize treatment.

This review will cover the current clinical evidence behind the cardiovascular management of spinal cord pathology before introducing autoregulation as an essential factor of spinal cord physiology. Furthermore, we will discuss new developments in autoregulation that are ripe for application to the clinic and show the potential for spinal cord autoregulation to improve outcomes.

Acute mean arterial pressure management in SCI

Current clinical practice guidelines (2013 update)

The need for an understanding of autoregulation is especially evident in traumatic SCI. Several cardiovascular complications can occur during the secondary phase of SCI that can worsen the injury. Most dramatically, SCIs at the level of T6 or higher can result in autonomic dysregulation, systemic hypotension, and arrhythmias [1, 15,16,17]. These complications, while morbid, are manifestations of direct injury to the sympathetic center in the thoracic cord, rather than vascular autoregulation dysfunction, and thus are not covered in detail here. Independent of this, decreased perfusion at the site of injury has also been noted. Furthermore, it has been shown that reduced perfusion is related to worse patient outcomes [18, 19].

The current guidelines for the management of SCI, however, offer only a Level III recommendation to maintain MAP at 85-90 mmHg for seven days. These guidelines were published in 2013 by an author group from the Joint Section on Spine and Peripheral Nerves of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and Congress of Neurological Surgeons, based on previous recommendations from 2002 in a systematic review by Hadley et al. [13, 20]. Since then, there has not been much new evidence to change recommendations substantially. Clinically, adherence to this goal also remains a challenge. The amount of time spent within MAP goals depends on the care setting, and there is critical time before transfer to specialized centers when pressure remains well below these goals [21, 22]. Thus, there is a clinical need for more evidence backing cardiovascular management after SCI.

Spinal cord perfusion pressure: the real driver of blood flow

Part of the reason that MAP has been such an unreliable predictor of outcome may lie in its partial role in driving the perfusion of the cord. MAP acts as the forward pressure of blood flow, pushing blood into tissue. However, intraspinal pressure (ISP) provides significant pressure against the direction of flow in the spinal cord, which is an enclosed space [23]. This is important in the spine, where secondary injury results in increased ISP, which partially contributes to the decreased flow at the site of injury [24]. Thus, we infer that a narrow range of MAP, which is unpredictable based on current data, is needed to maximize tissue perfusion.

As a result, many groups have begun to look at spinal cord perfusion pressure (SCPP), which is the difference between MAP and ISP [25]. This is analogous to cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP), the difference between MAP and intracranial pressure (ICP), which is already extensively used in clinical management of TBI [4]. Within ischemic injury after aortic aneurysm repair, ISP is even more relevant, as we already use SCPP rather than MAP to improve blood flow [26]. Several studies have also found that SCPP is a better predictor of outcome after traumatic SCI than MAP [27,28,29]. Outcome in these cases was determined by improvement in ASIA Impairment Scale motor score, as detailed in the ASIA/ISCoS International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury.

Other studies have used SCPP monitoring to predict an optimal SCPP value [19] and have shown that higher SCPP results in better preservation of sensory evoked potentials [30]. Applying SCPP monitoring to clinical patients has also shown promise in improving sequelae of SCI, such as motor function [31], breathing [32], and anal sphincter function [33]. Unlike CPP, SCPP is complicated further by the fact that it can vary based on the spinal level and distance from injury at which ISP is measured [34].

As a result, several attempts have been made to improve SCPP through CSF drainage (CSFD) and expansile duraplasty. Preclinically, the results have been promising, with CSFD resulting in improved blood flow [35], Unfortunately, the evidence in clinical studies has not reached statistical significance, as the size of most of these studies is limited due to the relative rarity of SCI [36, 37].

Limits of generalized MAP thresholds

Although the evidence points to the need to augment spinal cord perfusion with MAP management combined with some form of ISP management [38], a vital piece of the story still needs to be added. In healthy people, the brain and spine have adapted to changes in MAP through autoregulation. Different patients with SCI may have various levels of autoregulation impairment. Thus, one standardized MAP or SCPP threshold clearly will not be optimal for each patient. In TBI, this has been understood for years [4], and it is time for similar wisdom to be applied to the care of SCI. Directly measuring autoregulation has the potential to provide more tailored, patient-specific goals for MAP and ISP management.

Autoregulation metrics: how do we measure autoregulation?

Before applying autoregulation principles to clinical management, we must first understand how it is quantified. To measure autoregulation, both arterial pressure and blood flow signals are needed. Most commonly, the arterial blood pressure signal comes from an arterial line [39,40,41]. On the other hand, many techniques can measure blood flow. In the brain, these techniques have been extensively evaluated and compared [42]. However, most techniques face more significant challenges in the spine due to the vertebrae, the smaller size of the cord, and confounding measurements from other tissues. A summary of the knowledge and technologies available between the brain and the spine is detailed in Table 1.

Three methods are most common in the spine: ultrasound [43,44,45,46,47,48], near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) [49,50,51], and laser Doppler flowmetry [52]. As we cover later, NIRS has had good clinical uptake due to ease of use, but otherwise, none of these has emerged as the clear best option. This may be partially due to each measurement only correlating to volumetric flow, the volume of blood delivered to tissue over time. Regardless of the blood flow measurement technique, once a high-resolution, accurate blood flow signal is acquired, several analysis techniques exist to evaluate autoregulation.

Static autoregulation

The Lassen curve

The idea of autoregulation in the CNS became established dogma with the publication of Niels Lassen’s 1959 study [2]. By compiling data from previous studies, he showed that blood flow to the brain was constant in a MAP range of approximately 65-150 mmHg. The plot from this figure eventually became known as the Lassen curve (Fig. 1a) and has become core knowledge in neurology, neuroanesthesia, and neurosurgery [39].

a The classic Lassen curve showing the autoregulatory plateau, where spinal cord blood flow remains constant at a range of MAP at equilibrium. b If MAP changes within the autoregulatory plateau, blood flow momentarily increases, before returning to baseline, showing dynamic autoregulation. c If dynamic autoregulation is impaired, a step change in MAP results in spinal cord blood flow not returning to baseline. This could occur in healthy cord if MAP is outside of the autoregulatory plateau, as shown in this example.

It is important to note, however, that although most of the blood flow measurement techniques were accurate, they were limited in sampling rate [53, 54]. Thus, most experiments involved holding MAP at a specific value, allowing blood flow to reach equilibrium before measuring. The Lassen curve and quantification on similar timescales are thus known as static autoregulation [39]. While this information helps understand an organ’s perfusion at different MAP levels, it cannot capture the time dynamics of the blood flow response to fast MAP changes. This faster behavior is instead captured in the field of dynamic autoregulation. Also, autoregulatory curves are divergent between individuals and can vary even for a single individual due to clinical changes over time. Since full Lassen curve measurement is slow, it may miss some temporal changes in an individual patient.

Static autoregulation in the spinal cord

The Lassen curve for the spinal cord was generated in the 1970s in monkeys, showing a similar blood flow plateau as the brain in a MAP range of 50-150 mmHg (Fig. 1a) [53, 54]. This was preserved in the thoracic cord even after a total cervical cord section [55], supporting the theory of this being a local phenomenon independent of the autonomic nervous system. The same authors went on to demonstrate that α-adrenergic blockade abolished the plateau [56], while β-adrenergic blockade resulted in no increase in blood flow even beyond 150 mmHg [57]. Although this suggests a role for the sympathetic nervous system in autoregulation, whether the sloped portions of the Lassen curve have any significance beyond a breakdown of autoregulation remains unclear. In the years since, many studies have measured the phenomenon of static spinal cord autoregulation across multiple animal models and flow measurement techniques [51, 53, 54, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78]. These studies are summarized in Table 2. Unfortunately, only two of these studies incorporated data from humans, and both measured only two points on the Lassen curve.

Dynamic autoregulation

MAP challenges and the autoregulatory index

Beyond static autoregulation, using blood flow measurement techniques with higher sampling rates led to exploring how blood flow in the CNS responds dynamically to changes in MAP. This concept is known as dynamic autoregulation [39, 79,80,81]. In summary, after a “step” change in MAP (Fig. 1b), blood flow sharply changes as well, in the same direction as pressure. However, within seconds, healthy CNS vasculature reacts to the change and returns the blood flow value to the pre-change baseline (Fig. 1b). Autoregulation is impaired if the flow does not fully return to baseline (Fig. 1c) or returns to baseline sluggishly. As such, the equilibrium values of flow pre- and post-MAP change correspond to points on the Lassen curve (Fig. 1), and the recovery behavior signifies a new way of looking at autoregulation.

Tiecks et al. quantified this recovery in time using an index known as the autoregulatory index (ARI) by fitting the MAP and blood flow changes to a model [82]. This single value, with a range of 0-9, was a simple way to represent the level of dynamic autoregulation. A value of 5 ± 1 was considered average healthy autoregulation, with a return to baseline within 5-10 seconds, while an ARI of 0 indicated the absence of autoregulation. A value of 1-4 indicated sluggish autoregulation as described above. In this case, although the CNS may have restored blood flow to baseline after a change in MAP, the delayed recovery could cause further damage. This model also included values higher than 5, indicating rapid autoregulation with a quicker-than-average return to baseline.

The authors found that ARI correlated well with measures of static autoregulation derived from the slope of the Lassen curve in a group of patients. This is important because an accurate measurement of the Lassen curve requires measuring flow at a range of MAP, which limits its clinical utility. However, this correlation implies that blood flow does not need to be measured in the full range of MAPs to detect dysautoregulation [82]. Rather, a simple blood pressure challenge could ideally extract the necessary information for clinical decision-making.

Transfer function analysis

Another innovation came with the introduction of transfer function analysis to the field, first presented in the brain in 1990 [83]. In essence, the technique uses an input (MAP) and an output (blood flow) signal to measure a transfer function, which represents how information in the input is “transferred” to the output. (Fig. 2a). The first application of the technique to measure autoregulation used coherence [83], which is bounded by 0 and 1. This value resembles a correlation coefficient, where 0 means that no changes in MAP are transferred to blood flow, and autoregulation is intact. Conversely, at a coherence of 1, the entirety of the changes in blood flow can be explained by MAP, indicating no autoregulation (Fig. 2b).

a Idealized MAP changes with the signal frequency increasing as time increases. b Spinal cord blood flow with coherence of 1 in light red and <1 in dark red. Coherence of <1 indicates that a signal other than MAP is influencing spinal cord blood flow changes, which is the case with intact autoregulation. c Low gain (dark red) signifies low amount of signal being transferred from MAP to blood flow, as autoregulation is intact. Impaired autoregulation (light red) means more MAP changes are transferred to blood flow. d With intact regulation, there is a slight positive phase shift (dark red), signifying that the vasculature is responding to MAP changes. As autoregulation becomes impaired, phase shift goes to 0 (light red).

Transfer function analysis was further expanded to look at transfer function gain and phase [84,85,86], which provide extra detail. Gain, or magnitude, quantifies the amount of signal transferred. This metric can be thought of as a “volume knob,” where given one input, higher gain results in a relatively “louder” output. (Fig. 2c). An autoregulating system will have low gain, symbolizing low amount of pressure fluctuations being transferred to flow. Higher gain in this case indicates the magnitude of dysautoregulation [39].

Phase, on the other hand, in units of degrees, represents the timing of signal transfer. This concept is the least intuitive but can be conceptualized during MAP oscillations. Essentially, an autoregulating system that corrects for MAP changes will reach a minimum blood flow and begin returning to baseline before MAP reaches its trough, almost “predicting” the changes and resulting in a positive phase shift (Fig. 2d). The phase shift also affects the speed of recovery from a step change in MAP, as described in the ARI section above. An ideal autoregulating system usually exhibits a phase shift of 40-50°. Outside the scope of this review, more in-depth and relevant explanations of dynamic autoregulation in the brain [39] and the theoretical concepts and implementation of transfer function analysis [40] have been provided.

Dynamic autoregulation in the spinal cord

Before the development of formal dynamic autoregulation techniques in the brain, continuous blood flow signals had been recorded in the spinal cord in monkeys, rabbits, and dogs [68, 77, 78]. However, this was done before the development of the techniques mentioned above, and dynamic spinal autoregulation has yet to be formally analyzed. Thus, although the axes in Figs. 1b, c and 2b–d. are labeled as spinal cord blood flow, the dynamic behavior is extrapolated from the brain.

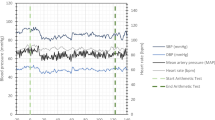

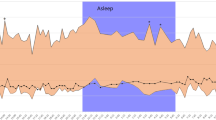

Correlation metrics

Another method of quantification of autoregulation employs correlation metrics. The correlation coefficient between blood flow and MAP is calculated in three- to five-minute windows (Fig. 3a, b) [6]. Similarly to coherence, the greater the correlation, the more blood flow depends on pressure, and the more significant the impairment in autoregulation (Fig. 3c, d). This method is often employed in continuous monitoring over a long period. Furthermore, by plotting the correlation metric against MAP, one can find the MAP range at which the correlation is the lowest. This would indicate the optimal blood pressure range at which a patient autoregulates most effectively, providing an individualized MAP goal (Fig. 3e) [87, 88]. However, since the correlations are calculated over minutes, they miss some finer dynamics that can be elucidated using dynamic techniques above. Furthermore, just because a certain MAP goal results in optimal autoregulation, it is not known whether this results in the optimal blood flow for healing [3]. Further investigation is needed to deconvolute the two potential MAP goals.

a Mean arterial pressure and b spinal cord blood flow recorded over an extended period. Five-minute periods are processed to obtain the correlation between MAP and blood flow. c Intact autoregulation results in a correlation close to 0, while d impaired autoregulation results in a correlation closer to 1. e Plotting correlation of each period against the mean MAP of that chunk often shows an MAP at which correlation is minimal (and thus autoregulation is maximal). This may be the optimal MAP target for that patient.

There is also an important practical issue with clinical management incorporating correlation metrics. Targeting a narrow range of MAP to optimize any of the correlation metrics (in the brain or spine) makes it difficult to calculate them at future timepoints, since accurate computation requires MAP to fluctuate over a wide range.

NIRS and COx

Although initially developed using transcranial Doppler ultrasound, the technique was eventually adapted to use near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) [89, 90]. NIRS does not directly measure blood flow but instead measures tissue-oxygenated hemoglobin saturation [90]. The resulting autoregulation correlation index is COx, or cerebral oximetry index. This method quickly gained popularity due to its easy setup. However, it has poor spatial specificity and is also limited in depth. Furthermore, as a tissue oxygenation measurement, it is not a perfect replacement for blood flow measurements, so its physiologic meaning is often questioned [91]. The benefits, mainly the ease of use of the technique and noninvasiveness, however, have resulted in many publications utilizing NIRS in patients [92, 93].

Using NIRS is somewhat more complex in the spine, due to the depth and small size of the cord. As a result, few studies have measured autoregulation using COx and NIRS. As mentioned above, the Lassen curve has been measured in the spinal cord using NIRS, although a full plateau was not seen in the spine in that study [51]. Additionally, NIRS applied to the skin over the spine is likely measuring paraspinal muscle blood flow. Although it correlates with spinal cord flow, it is not an exact replacement [94]. Furthermore, correlation indices derived from different measurement modalities do not always correlate with each other, causing additional confusion [95, 96].

SCPP and sPRx

Due to the difficulties with clinical blood flow measurement, ICP and ISP have also been used as surrogates for blood flow in the brain and spine [19, 97, 98]. Similarly to COx as described above, a moving correlation coefficient, PRx, can be calculated. The spinal version, sPRx, has been used similarly in SCI patients to find an optimal SCPP that minimizes the correlation, and thus maximizes this measure of autoregulation [97]. A follow-up retrospective study was able to show that deviation from this target SCPP resulted in worse outcomes in SCI patients [19]. Again, since ISP is not a direct measure of blood flow, this is not directly measuring autoregulation. However, it does suggest that personalized SCPP targets may exist, and that they are clinically significant even if they are based on ISP and not blood flow.

Integration of techniques

As these different techniques for autoregulation measurement have emerged, a remaining question is the consistency between these methods. Since all these techniques measure the same physiologic phenomenon, they generally correlate [82, 99]. However, each method is sensitive to signal noise in different ways. This means that although a perfectly noiseless signal might result in similar conclusions of autoregulation status, real-world, noisy signals can cause substantial disagreement between the methods. Within different care settings, this noise can also occur differently. For example, in the operating room, noise may occur due to events related to the surgery. In contrast, in the ICU, it may occur due to changes in the patient’s overall physiology.

Furthermore, in the study of cerebral autoregulation, increased importance has been placed on using CPP as the input variable for autoregulation [4]. We have already mentioned the importance of its spinal correlate, spinal cord perfusion pressure (SCPP), in clinical management. However, SCPP has not yet been used to quantify autoregulation in the spine, likely due to the newer role of CSF drainage in the care of SCI. Adding this variable may provide improved insight into perfusion following SCI.

Confounders of autoregulation

PaCO2

To apply concepts of autoregulation to effects on perfusion clinically, it is also essential to understand several other important variables that regulate spinal cord blood flow. One of the most important regulators is the partial pressure of CO2 in the arterial blood (paCO2). Cerebral blood flow is well-established to be directly proportional to paCO2 through a pH-related mechanism. Multiple other investigators have corroborated this relationship in the spinal cord in monkeys and dogs [54, 68]. In the context of autoregulation, it is essential to measure arterial CO2 content, to ensure that changes in paCO2 cannot explain any changes in blood flow. Additional essential physiologic variables to consider include temperature [100] and arterial oxygen content [53].

Pharmacological effects

Clinically, SCI patients in the hospital receive a host of drugs to maintain homeostasis. These drugs are often vasoactive and thus can modulate how blood vessels respond to changes in pressure. They can also impact cardiac centrality and fluid distribution. Furthermore, these effects are all dose-dependent. As a result, when considering autoregulation’s prognostic utility and therapeutic implications, it is important to understand how these drugs may confound its measurement. For example, vasopressors and inotropes have been shown to affect blood flow in the CNS in different ways, depending on the mechanism with which they raise MAP [50, 82, 101, 102]. Thus, when measuring autoregulation while using these drugs, there may be significant confounding.

Anesthetic and sedative drugs, which are widely used in clinical circumstances surrounding spinal cord pathology, have potentially profound effects on autoregulation. Multiple studies have shown inhibition of autoregulation from halogenated ether inhaled anesthetics in patients as well as various animal models, which are a mainstay of general anesthesia practice [103,104,105,106]. Some studies have also demonstrated preserved autoregulation with this drug class [72, 107], but generally, these drugs should be avoided or used only at low doses if accurate autoregulation determination is necessary. On the other hand, other anesthetics such as propofol, ketamine, NO2, and anesthetic adjuncts such as opiates and dexmedetomidine have been shown to preserve static autoregulation in the spine and dynamic autoregulation in the brain, both in humans and rats [104, 105, 108, 109]. These anesthetic strategies are preferred in a setting where autoregulation measurement is performed, although clinical judgement about anesthesia care must incorporate multiple factors of which autoregulation measurement is only one.

Spinal autoregulation in disease

Traumatic spinal cord injury

Generally, there is an evolving consensus that autoregulation is impaired after SCI [20]. The preclinical and clinical studies on this subject are summarized in Table 3 [43, 52, 55, 61, 62, 70, 110,111,112,113]. The loss of autoregulation has been shown to be dependent on injury severity [61, 111] as well as distance from the injury [52, 55] Some studies have conversely shown preserved autoregulation after injury [62, 113], highlighting variability in effect. Likely, this is due to multiple factors such as the distance of the measurement site from the injury, the measurement technique, the injury severity, and other physiological confounds. Again, it should be noted that only one of these studies was performed in humans, and with only two MAP values from the Lassen curve. More work needs to be done before a concrete understanding can be reached.

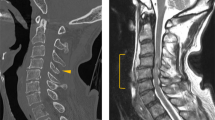

Spinal cord ischemia and aortic aneurysms

Another pathology in which spinal cord autoregulation plays a role is in spinal cord ischemic injury following thoracic aortic aneurysm surgery. Similarly to trauma, CSF drainage has become a cornerstone of prophylactic treatment for this feared complication [114, 115]. As a result, NIRS has been used to measure spinal cord perfusion in humans directly [116,117,118]. In one of these studies, correlation of NIRS measurements with MAP was low before surgery, and increased after [118], indicating that autoregulation may be impaired. Beyond this, however, there has not been further work to quantify autoregulation in this pathology. A better understanding of this may help with developing further treatments.

Other pathologies

Other than trauma and ischemic injury, spinal autoregulation research has been sparse. In the brain, autoregulation has been shown to be impaired in ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, tumor, and sepsis. [87, 119,120,121]. Even though these diseases and more often have correlates in the spine, we have no understanding of spine-specific nuances here. We can only extrapolate results from the brain. As more spinal cord blood flow monitoring modalities enter clinical use, it is imperative that we also investigate these pathologies so that we can better understand how pressure affects blood flow and thus outcomes.

Perioperative considerations

In the setting of general anesthesia, there is substantial consideration given to the importance of preserving cerebral perfusion. As a result, it has been recommended not to decrease MAP by more than 20% below baseline during surgery. This cutoff is higher in trauma, when autoregulation is impaired [122]. During major surgery for brain tumors, autoregulation was also shown to be impaired, which may influence anesthesia management [121], although this is not consistent across studies [123]. Regardless, no similar work has been performed in the spine, leaving major knowledge gaps when it comes to anesthesia for spine surgery.

Clinical practice: applying autoregulation to direct patient care

Examples from the brain

Now that we have summarized our understanding of autoregulation and its role in spinal cord disease, we can consider it in relation to direct patient management. The best example of autoregulation being used to direct care is found in two ongoing trials in TBI.

One of these trials is the Phase II COGiTATE Trial, which uses PRx, the correlation between CPP and ICP as a surrogate for autoregulation as described above [10]. As described earlier, clinicians determine an “optimal” CPP goal based on the value that results in the minimum correlation coefficient, and thus maximizes autoregulation (Fig. 3) [5]. Maintaining patients on this optimal CPP is safe and feasible, and could also be adapted to SCPP. However, this technique uses ICP instead of blood flow as the output. As a result, even the CPP that results in the best ICP regulation may not be the best for perfusion [3]. Furthermore, as mentioned above, even the optimal MAP for autoregulation may not result in the optimal blood flow for healing.

To address this issue, invasive brain tissue oxygenation (PbtO2) has been recommended as a further monitoring variable. The risks of PbtO2 monitoring are similar to those of ICP, which is well within the neurosurgical treatment domain [11]. As a result, it is generally reserved for insults of a certain severity. As part of recent guidelines, PbtO2 can be measured during a controlled decrease in CPP to determine the level of patient autoregulation after TBI. If the patient is properly autoregulating, the CPP thresholds may be reduced below current guidelines, thus alleviating some of the harms that come from elevated CPP [4]. A separate phase II trial, BOOST-II, has shown that PbtO2-directed management is safe and feasible, and demonstrated initial trends towards improved patient outcomes [11]. The upcoming BOOST-III trial using this algorithm will be powered for clinical efficacy [12], and may represent the first time that management utilizing brain oxygenation enters clinical care prime time.

Other than TBI, many other cerebral pathologies have been shown to affect cerebral autoregulation [119]. However, none have utilized autoregulation measurements to direct treatment.

Knowledge gaps: what we are missing in the spine

The major limiting factor in the spine is the lack of a good blood flow/oxygenation monitoring modality. As mentioned above, transcranial Doppler has been an accurate tool for measuring cerebral blood flow and autoregulation [82], but a similar blood vessel to the middle cerebral artery has not been identified in the spine. NIRS has been used in the spine, but suffers from poor spatial resolution, and is likely measuring paraspinal muscle blood flow, which is only a correlate for spinal cord flow [94]. Finally, an invasive tissue oxygen-based sensor, like that used in the BOOST trials, is not as simple in the spinal cord. Generally, this monitor involves invasive placement in the brain parenchyma, which is relatively well-tolerated. However, unlike the brain, the spinal cord is almost entirely “eloquent” tissue and tolerates parenchymal invasion significantly less than the brain. Although oxygenation monitoring has been done in the spine [124], there is significantly greater risk involved.

This point raises an interesting question in the context of multi-trauma, particularly in simultaneous TBI and SCI. Currently, since blood flow and oxygenation monitoring are limited to the brain, clinical decisions are likely to prioritize cerebral perfusion. However, with the higher eloquence of spinal cord tissue, optimizing its perfusion may yield better results for the patient. At the very least, concurrent monitoring is necessary to address this question.

Another interesting consideration stems from the rostro-caudal extent of the spinal cord. Injury at a specific level may impair autoregulation locally, but as we have discussed, it is likely preserved in distal healthy tissues. This has already been explored with sPRx, where there was variability in pressure reactivity over the length of the cord [125]. As a functional consequence of differentially impaired autoregulation, vasculature at the site of injury would not appropriately respond to a decrease in MAP. In contrast, vasculature in healthy tissue would respond through vasodilation. It is therefore possible that the vasodilation at the healthy tissue site may further shunt blood flow away from the injury beyond what might be expected with uniform impairment. With this theory, the opposite would also be true with an increase in MAP, where healthy vasculature would constrict, perhaps further diverting blood to the injury. It has already been shown in pig models that overly increasing blood flow can cause hemorrhage and further damage [126]. Further studies are needed to investigate this potential vascular steal phenomenon.

The anatomic blood supply to the cord may also influence autoregulation. Although there are radiculomedullary arteries that variably supply the cord at each spinal level, there are also larger arteries that are responsible for a wider extent of perfusion. These include vertebral arteries supplying the upper cervical levels and the artery of Adamkiewicz, which usually supplies the lower thoracic and upper lumbar cord. As a result of this complex vascular supply, the mid-thoracic region is considered a watershed area [127]. It is not well understood how the spatial relation of an injury to one of these major feeders relates to the loss of autoregulation, but one may hypothesize that an injury within the watershed zone has less collateral flow and thus would be more sensitive to impairment of autoregulation. Finally, the concept of posture plays an interesting role, as a seated patient would have a vertical spinal cord, while it would be horizontal in a supine patient. Impaired autoregulation may result in certain sections of the cord, especially the extremes at the upper cervical and the conus medullaris, being more sensitive to posture changes. Although acutely injured patients are usually supine, this may play a role later in the injury as they begin to recover.

Once a clinically useful spinal cord blood flow tool can be deployed, advancement of the clinical knowledge and utility of autoregulation can be accelerated using lessons learned from asking similar questions in the brain. Thus, we identify spinal cord blood flow and oxygenation monitoring as the current greatest obstacle to autoregulation-based spinal cord monitoring and treatment.

Conclusions and future directions

Maintenance of MAP is an essential aspect throughout neurological disease. As mentioned above, however, we have not yet optimized this aspect of treatment, especially in the spine. Generalized MAP thresholds that ignore patient heterogeneity likely contribute to the continuing uncertainty. Through trials such as the BOOST and COGiTATE trials, we have seen how autoregulation measurement can influence care in TBI. Although there may be differences in the cord, we can still apply similar strategies to spinal pathology.

Unfortunately, before reaching widespread clinical development and practice, several gaps need to be filled. Accurate autoregulation assessment depends on sufficient MAP changes and good blood flow measurement techniques, both of which have not been fully addressed in the cord. As more spinal cord blood flow measurement tools become available, we urge the general neurologist and neurosurgeon to use them throughout their practice, in combination with MAP challenges. With this data, we can begin to develop similar autoregulation-directed MAP goals as we already use in the brain, bringing a more personalized approach to blood flow management in the spine.

References

Jia X, Kowalski RG, Sciubba DM, Geocadin RG. Critical care of traumatic spinal cord injury. J Intensive Care Med. 2013;28:12–23.

Lassen NA. Cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption in man. Physiol Rev. 1959;39:183–238.

Chesnut RM. A conceptual approach to managing severe traumatic brain injury in a time of uncertainty. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1345:99–107.

Chesnut R, Aguilera S, Buki A, Bulger E, Citerio G, Cooper DJ, et al. A management algorithm for adult patients with both brain oxygen and intracranial pressure monitoring: the seattle international severe traumatic brain injury consensus conference (SIBICC. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:919–29.

Aries MJH, Czosnyka M, Budohoski KP, Steiner LA, Lavinio A, Kolias AG, et al. Continuous determination of optimal cerebral perfusion pressure in traumatic brain injury*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2456–63.

Czosnyka M, Smielewski P, Kirkpatrick P, Menon DK, Pickard JD. Monitoring of cerebral autoregulation in head-injured patients. Stroke. 1996;27:1829–34.

Shekhar S, Liu R, Travis OK, Roman RJ, Fan F. Cerebral autoregulation in hypertension and ischemic stroke: a mini review. J Pharm Sci Exp Pharmacol. 2017;2017:21–7.

Olsen MH, Capion T, Riberholt CG, Bache S, Ebdrup SR, Rasmussen R, et al. Effect of controlled blood pressure increase on cerebral blood flow velocity and oxygenation in patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2023;67:1054–60.

Alkhachroum A, Megjhani M, Terilli K, Rubinos C, Ford J, Wallace BK, et al. Hyperemia in subarachnoid hemorrhage patients is associated with an increased risk of seizures. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2020;40:1290–9.

Tas J, Beqiri E, Van Kaam RC, Czosnyka M, Donnelly J, Haeren RH, et al. Targeting autoregulation-guided cerebral perfusion pressure after traumatic brain injury (COGiTATE): a feasibility randomized controlled clinical trial. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38:2790–800.

Okonkwo DO, Shutter LA, Moore C, Temkin NR, Puccio AM, Madden CJ, et al. Brain oxygen optimization in severe traumatic brain injury phase-II: A phase II randomized trial. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:1907–14.

Bernard F, Barsan W, Diaz-Arrastia R, Merck LH, Yeatts S, Shutter LA. Brain oxygen optimization in severe traumatic brain injury (BOOST-3): a multicentre, randomised, blinded-endpoint, comparative effectiveness study of brain tissue oxygen and intracranial pressure monitoring versus intracranial pressure alone. BMJ Open. 2022;12:1–9.

Walters BC, Hadley MN, Hurlbert RJ, Aarabi B, Dhall SS, Gelb DE, et al. Guidelines for the management of acute cervical spine and spinal cord injuries: 2013 update. Neurosurgery. 2013;60:82–91.

Guan B, Anderson DB, Chen L, Feng S, Zhou H. Global, regional and national burden of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e075049.

Stevens RD, Bhardwaj A, Kirsch JR, Mirski MA. Critical care and perioperative management in traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2003;15:215–29.

Wuermser LA, Ho CH, Chiodo AE, Priebe MM, Kirshblum SC, Scelza WM. Spinal Cord Injury Medicine. 2. acute care management of traumatic and nontraumatic injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:55–61.

Furlan JC, Fehlings MG. Cardiovascular complications after acute spinal cord injury: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25:E13.

Chen S, Gallagher MJ, Hogg F, Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S. Visibility graph analysis of intraspinal pressure signal predicts functional outcome in spinal cord injured patients. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35:2947–56.

Chen S, Smielewski P, Czosnyka M, Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S. Continuous monitoring and visualization of optimum spinal cord perfusion pressure in patients with acute cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:2941–9.

Hadley MN. Blood pressure management after acute spinal cord injury. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:58–62.

Tee JW, Altaf F, Belanger L, Ailon T, Street J, Paquette S, et al. Mean arterial blood pressure management of acute traumatic spinal cord injured patients during the pre-hospital and early admission period. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:1271–7.

Sharwood LN, Joseph A, Guo C, Flower O, Ball J, Middleton JW. Heterogeneous emergency department management of published recommendation defined hypotension in patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injury: a multi-centre overview. Emerg Med Australas. 2019;31:967–73.

Griffiths IR, Pitts LH, Crawford RA, Trench JG. Spinal cord compression and blood flow: I. The effect of raised cerebrospinal fluid pressure on spinal cord blood flow. Neurology. 1978;28:1145–51.

Khaing ZZ, Cates LN, Fischedick AE, Mcclintic AM, Mourad PD, Hofstetter CP. Temporal and spatial evolution of raised intraspinal pressure after traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:645–51.

Weber-Levine C, Judy BF, Hersh AM, Awosika T, Tsehay Y, Kim T, et al. Multimodal interventions to optimize spinal cord perfusion in patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injuries: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2022;37:729–39.

Etz CD, Weigang E, Hartert M, Lonn L, Mestres CA, Di Bartolomeo R, et al. Contemporary spinal cord protection during thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic surgery and endovascular aortic repair: a position paper of the vascular domain of the european association for cardio-thoracic surgery†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47:943–57.

Squair JW, Bélanger LM, Tsang A, Ritchie L, Mac-Thiong JM, Parent S, et al. Spinal cord perfusion pressure predicts neurologic recovery in acute spinal cord injury. Neurology. 2017;89:1660–7.

Squair JW, Bélanger LM, Tsang A, Ritchie L, Mac-Thiong JM, Parent S, et al. Empirical targets for acute hemodynamic management of individuals with spinal cord injury. Neurology. 2019;93:E1205–11.

Saadoun S, Chen S, Papadopoulos MC. Intraspinal pressure and spinal cord perfusion pressure predict neurological outcome after traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:452–3.

Gallagher MJ, López DM, Sheen HV, Hogg FRA, Zoumprouli A, Papadopoulos MC, et al. Heterogeneous effect of increasing spinal cord perfusion pressure on sensory evoked potentials recorded from acutely injured human spinal cord. J Crit Care. 2020;56:145–51.

Hogg FRA, Kearney S, Zoumprouli A, Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S, FRA H, et al. Acute spinal cord injury: correlations and causal relations between intraspinal pressure, spinal cord perfusion pressure, lactate-to-pyruvate ratio, and limb power. Neurocrit Care. 2021;34:121–9.

Visagan R, Boseta E, Zoumprouli A, Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S. Spinal cord perfusion pressure correlates with breathing function in patients with acute, cervical traumatic spinal cord injuries: an observational study. Crit Care. 2023;27:1–11.

Hogg FRA, Kearney S, Gallagher MJ, Zoumprouli A, Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S. Spinal cord perfusion pressure correlates with anal sphincter function in a cohort of patients with acute, severe traumatic spinal cord injuries. Neurocrit Care. 2021;35:794–805.

Werndle MC, Saadoun S, Phang I, Czosnyka M, Varsos GV, Czosnyka ZH, et al. Monitoring of spinal cord perfusion pressure in acute spinal cord injury. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:646–55.

Martirosyan NL, Kalani MYS, Bichard WD, Baaj AA, Fernando Gonzalez L, Preul MC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid drainage and induced hypertension improve spinal cord perfusion after acute spinal cord injury in pigs. Neurosurgery. 2015;76:461–8.

Theodore N, Martirosyan N, Hersh AM, Ehresman J, Ahmed AK, Danielson J, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid drainage in patients with acute spinal cord injury: a multi-center randomized controlled trial. World Neurosurg. 2023;177:140326.

Kwon BK, Curt AN, Belanger LM, Bernardo A, Chan D, Markez JA, et al. Intrathecal pressure monitoring and cerebrospinal fluid drainage in acute spinal cord injury: a prospective randomized trial. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;10:181–93.

Fehlings MG, Moghaddamjou A, Evaniew N, Tetreault LA, Alvi MA, Skelly AC, et al. The 2023 Ao spine-praxis guidelines in acute spinal cord injury: what have we learned? what are the critical knowledge gaps and barriers to implementation? Global Spine J. 2024;14:223S–230S.

Claassen JAHR, Thijssen DHJ, Panerai RB, Faraci FM. Regulation of cerebral blood flowin humans: Physiology and clinical implications of autoregulation. Physiol Rev. 2021;101:1487–559.

Panerai RB, Brassard P, Burma JS, Castro P, Claassen JAHR, van Lieshout JJ, et al. Transfer function analysis of dynamic cerebral autoregulation: A CARNet white paper 2022 update. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2023;43:3–25.

Claassen JA, Meel-van den Abeelen AS, Simpson DM, Panerai RB. Transfer function analysis of dynamic cerebral autoregulation: a white paper from the international cerebral autoregulation research network. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:665–80.

Panerai RB. Assessment of cerebral pressure autoregulation in humans - A review of measurement methods. Physiol Meas. 1998;19:305–38.

Soubeyrand M, Dubory A, Laemmel E, Court C, Vicaut E, Duranteau J. Effect of norepinephrine on spinal cord blood flow and parenchymal hemorrhage size in acute-phase experimental spinal cord injury. Eur Spine J. 2014;23:658–65.

Soubeyrand M, Laemmel E, Court C, Dubory A, Vicaut E, Duranteau J. Rat model of spinal cord injury preserving dura mater integrity and allowing measurements of cerebrospinal fluid pressure and spinal cord blood flow. Eur Spine J. 2013;22:1810–9.

Bruce M, DeWees D, Harmon JN, Cates L, Khaing ZZ, Hofstetter CP. Blood flow changes associated with Spinal Cord Injury assessed by non-linear doppler contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2022;48:1410–9.

Khaing ZZ, Cates LN, Hyde JE, Hammond R, Bruce M, Hofstetter CP. Transcutaneous contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging of the posttraumatic spinal cord. Spinal Cord. 2020;58:695–704.

Khaing ZZ, Cates LN, Hyde J, Dewees DM, Hammond R, Bruce M, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound for assessment of local hemodynamic changes following a rodent contusion Spinal Cord Injury. In: Military Medicine. Oxford Academic; 2020. p. 470–5.

Routkevitch D, Soulé Z, Kats N, Baca E, Hersh AM, Kempski-Leadingham KM, et al. Non-contrast ultrasound image analysis for spatial and temporal distribution of blood flow after spinal cord injury. Sci Rep. 2024;14:714.

Cheung A, Tu L, Manouchehri N, Kim KT, So K, Webster M, et al. Continuous optical monitoring of spinal cord oxygenation and hemodynamics during the first seven days post-injury in a porcine model of acute Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37:2292–301.

Streijger F, So K, Manouchehri N, Gheorghe A, Okon EB, Chan RM, et al. A direct comparison between norepinephrine and phenylephrine for augmenting spinal cord perfusion in a porcine model of Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35:1345–57.

Kurita T, Kawashima S, Morita K, Nakajima Y. Spinal cord autoregulation using near-infrared spectroscopy under normal, hypovolemic, and post-fluid resuscitation conditions in a swine model: A comparison with cerebral autoregulation. J Intensive Care. 2020;8:1–10.

Gallagher MJ, Hogg FRA, Zoumprouli A, Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S. Spinal cord blood flow in patients with acute Spinal Cord Injuries. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36:919–29.

Griffiths IR. Spinal cord blood flow in dogs: The effect of blood pressure. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1973;36:914–20.

Kobrine AI, Doyle TF, Martins AN. Autoregulation of Spinal Cord Blood Flow. Neurosurgery. 1975;22:573–81.

Kobrine AI, Doyle TF, Newby N, Rizzoli HV. Preserved autoregulation in the rhesus spinal cord after high cervical cord section. J Neurosurg. 1976;44:425–8.

Kobrine AI, Evans DE, Rizzoli HV. The effect of alpha adrenergic blockade on spinal cord autoregulation in the monkey. J Neurosurg. 1977;46:336–41.

Kobrine AI, Evans DE, Rizzoli HV. The role of the sympathetic nervous system in spinal cord autoregulation. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1977;64:54–5.

Lobosky JM, Hitchon PW, Torner JC, Yamada T. Spinal cord autoregulation in the sheep. Curr Surg. 1984;41:264–7.

Hitchon PW, Lobosky JM, Yamada T, Johnson G, Girton RA. Effect of hemorrhagic shock upon spinal cord blood flow and evoked potentials. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:849–57.

Sato M, Pawlik G, Heiss WD. Comparative studies of regional CNS blood flow autoregulation and responses to CO2 in the cat. effects of altering arterial blood pressure and PaCO2 on rCBF of cerebrum, cerebellum, and spinal cord. Stroke. 1984;15:91–7.

Smith AJK, McCreery DB, Bloedel JR, Chou SN. Hyperemia, CO2 responsiveness, and autoregulation in the white matter following experimental spinal cord injury. J Neurosurg. 1978;48:239–51.

Ohashi T, Morimoto T, Kawata K, Yamada T, Sakaki T. Correlation between spinal cord blood flow and arterial diameter following acute spinal cord injury in rats. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1996;138:322–9.

Kling TF, Fergusson NV, Leach AB, Hensinger RN, Lane GA, Knight PR. The influence of induced hypotension and spine distraction on canine spinal cord blood flow. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1985;10:873–88.

Marcus ML, Heistad DD, Ehrhardt JC, Abboud FM. Regulation of total and regional spinal cord blood flow. Circ Res. 1977;41:128–34.

Holtz A, Nystrom B, Gerdin B. Regulation of spinal cord blood flow in the rat as measured by quantitative autoradiography. Acta Physiol Scand. 1988;133:485–93.

Tsuji T, Matsuyama Y, Sato K, Iwata H. Evaluation of spinal cord blood flow during prostaglandin E1-induced hypotension with power doppler ultrasonography. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:31–6.

Sakamoto T, Shimazaki S, Monafo WW. [14 C]butanol distribution: a new method for measurement of spinal cord blood flow. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:H953–9.

Sadanaga M, Kano T, Hashiguchi A, Sakamoto M, Higashi K, Morioka T. Simultaneous laser-doppler flowmetry of canine spinal cord and cerebral blood flow: Responses to PaCO2 and blood pressure changes. J Anesth. 1993;7:427–33.

Shimoji K, Sato Y, Endoh H, Taga K, Fujiwara N, Fukuda S. Relation between spinal cord and epidural blood flow. Stroke. 1987;18:1128–32.

Senter HJ, Venes JL. Loss of autoregulation and posttraumatic ischemia following experimental spinal cord trauma. J Neurosurg. 1979;50:198–206.

Metzger H, Hartmann M, Wadouh F. The influence of hemorrhagic hypotension on spinal cord tissue oxygen tension. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1986;200:223–32.

Jacobs HK, Lieponis JV, Bunch WH, Barber MJ, Salem MR. The influence of halothane and nitroprusside on canine spinal cord hemodynamics. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1982;7:35–40.

Young W, DeCrescito V, Tomasula JJ. Effect of sympathectomy on spinal blood flow autoregulation and posttraumatic ischemia. J Neurosurg. 1982;56:706–10.

Hickey R, Albin MS, Bunegin L, Gelineau J. Autoregulation of spinal cord blood flow: Is the cord a microcosm of the brain? Stroke. 1986;17:1183–9.

Rubinstein A, Arbit E. Spinal cord blood flow in the rat under normal physiological conditions. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:882–6.

Ide R, Fukusaki M, Yamaguchi K, Matsumoto M, Ogata K, Sumikawa K. Effect of controlled hypotension induced by prostaglandin E1 on evoked spinal cord potential and spinal cord blood flow. Japanese Journal of Anesthesiology. 1997;46:1345–6.

Field EJ, Grayson J, Rogers AF. Observations on the blood flow in the spinal cord of the rabbit. J Physiol. 1951;114:56–70.

Kindt GW. Autoregulation of spinal cord blood flow. Eur Neurol. 1971;6:19–23.

Aaslid R, Lindegaard KF, Sorteberg W, Nornes H. Cerebral autoregulation dynamics in humans. Stroke. 1989;20:45–52.

Aaslid R, Newell DW, Stooss R, Sorteberg W, Lindegaard KF. Assessment of cerebral autoregulation dynamics from simultaneous arterial and venous transcranial doppler recordings in humans. Stroke. 1991;22:1148–54.

Lindegaard KF, Lundar T, Wiberg J, Sjøberg D, Aaslid R, Nornes H. Variations in middle cerebral artery blood flow investigated with noninvasive transcranial blood velocity measurements. Stroke. 1987;18:1025–30.

Tiecks FP, Lam AM, Aaslid R, Newell DW. Comparison of static and dynamic cerebral autoregulation measurements. Stroke. 1995;26:1014–9.

Giller CA. The frequency-dependent behavior of cerebral autoregulation. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:362–8.

Panerai RB, Kelsall AWR, Rennie JM, Evans DH. Analysis of cerebral blood flow autoregulation in neonates. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1996;43:779–88.

Panerai RB, Coughtrey H, Rennie JM, Evans DH. A model of the instantaneous pressure-velocity relationships of the neonatal cerebral circulation. Physiol Meas. 1993;14:411–8.

Panerai RB, Rennie JM, Kelsall AWR, Evans DH. Frequency-domain analysis of cerebral autoregulation from spontaneous fluctuations in arterial blood pressure. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1998;36:315–22.

Rosenblatt K, Walker KA, Goodson C, Olson E, Maher D, Brown CH, et al. Cerebral autoregulation–guided optimal blood pressure in sepsis-associated encephalopathy: a case series. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;35:1453–64.

Steiner LA, Czosnyka M, Piechnik SK, Smielewski P, Chatfield D, Menon DK, et al. Continuous monitoring of cerebrovascular pressure reactivity allows determination of optimal cerebral perfusion pressure in patients with traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:733–8.

Brady KM, Lee JK, Kibler KK, Smielewski P, Czosnyka M, Easley RB, et al. Continuous time-domain analysis of cerebrovascular autoregulation using near-infrared spectroscopy. Stroke. 2007;38:2818–25.

Tsuji M, Saul JP, du Plessis A, Eichenwald E, Sobh J, Crocker R, et al. Cerebral intravascular oxygenation correlates with mean arterial pressure in critically Ill premature infants. Pediatrics. 2000;106:625–32.

Olsen MH, Riberholt CG, Berg RMG, Møller K. Myths and methodologies: assessment of dynamic cerebral autoregulation by the mean flow index. Exp Physiol. 2024;109:614–23.

Hansen ML, Hyttel-Sørensen S, Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, Kooi EMW, Mintzer J, et al. Cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy monitoring (NIRS) in children and adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatr Res. 2022; https://www.nature.com/articles/s41390-022-01995-z.

Yang M, Yang Z, Yuan T, Feng W, Wang P. A Systemic review of functional near-infrared spectroscopy for stroke: current application and future directions. Front Neurol. 2019;10:58.

Etz CD, Kari FA, Mueller CS, Silovitz D, Brenner RM, Lin HM, et al. The collateral network concept: A reassessment of the anatomy of spinal cord perfusion. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:1020–8.

Kastenholz N, Megjhani M, Conzen-Dilger C, Albanna W, Veldeman M, Nametz D, et al. The oxygen reactivity index indicates disturbed local perfusion regulation after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: an observational cohort study. Crit Care. 2023;27:235.

Hoiland RL, Sekhon MS, Cardim D, Wood MD, Gooderham P, Foster D, et al. Lack of agreement between optimal mean arterial pressure determination using pressure reactivity index versus cerebral oximetry index in hypoxic ischemic brain injury after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2020;152:184–91.

Varsos GV, Werndle MC, Czosnyka ZH, Smielewski P, Kolias AG, Phang I, et al. Intraspinal pressure and spinal cord perfusion pressure after spinal cord injury: an observational study. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;23:763–71.

Czosnyka M, Smielewski P, Kirkpatrick P, Laing RJ, Menon D, Pickard JD. Continuous Assessment of the Cerebral Vasomotor Reactivity in Head Injury. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:11–9.

Liu X, Czosnyka M, Donnelly J, Cardim D, Cabeleira M, Lalou DA, et al. Assessment of cerebral autoregulation indices – a modelling perspective. Sci Rep. 2020;10:9600.

Sakamoto T, Monafo WW. The effect of hypothermia on regional spinal cord blood flow in rats. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:780–4.

Shirai K, Kawai Y, Ohhashi T. Contractile and relaxant responses of the canine isolated spinal artery to vasoactive substances. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;101:200–4.

Iida H, Ohata H, Iida M, Watanabe Y, Dohi S. Direct effects of α1- and α2-adrenergic agonists on spinal and cerebral pial vessels in dogs. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:479–85.

Hoffman WE, Edelman G, Kochs E, Werner C, Segil L, Albrecht RF. Cerebral autoregulation in awake versus isoflurane-anesthetized rats. Anesth Analg. 1991;73:753–7.

Strebel S, Lam A, Matta B, Mayberg TS, Aaslid R, Newell DW. Dynamic and static cerebral autoregulation during isoflurane, desflurane, and propofol anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:66–76.

Engelhard K, Werner C, Möllenberg O, Kochs E. S(+)-ketamine/propofol maintain dynamic cerebrovascular autoregulation in humans. Can J Anaesth. 2001;48:1034–9.

Ruesch A, Acharya D, Schmitt S, Yang J, Smith MA, Kainerstorfer JM. Comparison of static and dynamic cerebral autoregulation under anesthesia influence in a controlled animal model. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:1–16.

Brosnan RJ, Steffey EP, LeCouteur RA, Esteller-Vico A, Vaughan B, Liu IKM. Effects of isoflurane anesthesia on cerebrovascular autoregulation in horses. Am J Vet Res. 2011;72:18–24.

Werner C, Hoffman WE, Kochs E, Esch JSAA, Albrecht RF. The effects of propofol on cerebral and spinal cord blood flow in rats. Anesth Analg. 1993;76:971–5.

Hoffman WE, Werner C, Kochs E, Segil L, Edelman G, Albrecht RF. Cerebral and spinal cord blood flow in awake and fentanyl-n2o anesthetized rats: evidence for preservation of blood flow autoregulation during anesthesia. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1992;4:31–5.

Hukuda S, Mochizuki T, Ogata M. Effects of hypertension and hypercarbia on spinal cord tissue oxygen in acute experimental spinal cord injury. Neurosurgery. 1980;6:639–43.

Guha A, Tator CH, Rochon J. Spinal cord blood flow and systemic blood pressure after experimental spinal cord injury in rats. Stroke. 1989;20:372–7.

Dyste GN, Hitchon PW, Girton RA, Chapman M. Effect of hetastarch, mannitol, and phenylephrine on spinal cord blood flow following experimental spinal injury. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:228–35.

Westergren H, Farooque M, Olsson Y, Holtz A. Spinal cord blood flow changes following systemic hypothermia and spinal cord compression injury: an experimental study in the rat using laser-doppler flowmetry. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:74–84.

Wan IY, Angelini GD, Bryan AJ, Ryder I, Underwood MJ. Prevention of spinal cord ischaemia during descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;19:203–13.

Zvara DA. Thoracoabdominal aneurysm surgery and the risk of paraplegia: contemporary practice and future directions. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2002;34:11–7.

Luehr M, Mohr FW, Etz C. Indirect neuromonitoring of the spinal cord by near-infrared spectroscopy of the paraspinous thoracic and lumbar muscles in aortic surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;64:333–5.

Etz CD, von Aspern K, Gudehus S, Luehr M, Girrbach FF, Ender J, et al. Near-infrared spectroscopy monitoring of the collateral network prior to, during, and after thoracoabdominal aortic repair: a pilot study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;46:651–6.

Moerman A, Van Herzeele I, Vanpeteghem C, Vermassen F, François K, Wouters P. Near-infrared spectroscopy for monitoring spinal cord ischemia during hybrid thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Endovasc Ther. 2011;18:91–5.

Al-Kawaz M, Cho SM, Gottesman RF, Suarez JI, Rivera-Lara L. Impact of Cerebral autoregulation monitoring in cerebrovascular disease: a systematic review. Neurocrit Care. 2022;36:1053–70.

Rivera-Lara L, Zorrilla-Vaca A, Geocadin R, Ziai W, Healy R, Thompson R, et al. Predictors of outcome with cerebral autoregulation monitoring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:695–704.

Kahl U, Rademacher C, Harler U, Juilfs N, Pinnschmidt HO, Beck S, et al. Intraoperative impaired cerebrovascular autoregulation and delayed neurocognitive recovery after major oncologic surgery: a secondary analysis of pooled data. J Clin Monit Comput. 2022;36:765–73.

Xu Y, Vagnerova K. Anesthetic management of asleep and awake craniotomy for supratentorial tumor resection. Anesthesiol Clin. 2021;39:71–92.

Schmieder K, Schregel W, Harders A, Cunitz G. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation in patients undergoing surgery for intracranial tumors. Eur J Ultrasound. 2000;12:1–7.

Visagan R, Hogg FRA, Gallagher MJ, Kearney S, Zoumprouli A, Papadopoulos MC, et al. monitoring spinal cord tissue oxygen in patients with acute, severe traumatic spinal Cord Injuries. Crit Care Med. 2022;50:e477–86.

Hogg FRA, Gallagher MJ, Kearney S, Zoumprouli A, Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S. Acute Spinal Cord Injury: monitoring lumbar cerebrospinal fluid provides limited information about the injury site. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37:1156–64.

Cheung A, Streijger F, So K, Okon EB, Manouchehri N, Shortt K, et al. Relationship between Early Vasopressor Administration and Spinal Cord Hemorrhage in a Porcine Model of Acute Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37:1696–707.

Martirosyan NL, Feuerstein JES, Theodore N, Cavalcanti DD, Spetzler RF, Preul MC, et al. Blood supply and vascular reactivity of the spinal cord under normal and pathological conditions. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;15:238–51.

Acknowledgements

We disclose funding support from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, DARPA, Award Contract # N660012024075. In addition, D.R. discloses funding from the National Institutes of Health, NIH T32 GM136577 and F30 HL168823. N.V.T and R.G.G acknowledge funding from NIH R01 HL139158 and R01 HL071568.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: DR, CDM, KR, RGG, and NT; Methodology: DR, KJ, CWL, ADD; Software: DR; Validation and formal analysis: n/a; Investigation: DR, KJ, CWL, ADD; Resources: NVT, NT; Data curation: n/a; Writing – Original draft: DR, KJ, CWL; Writing – Review and Editing: all authors; Visualization: DR; Supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition: NVT, NT.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Routkevitch, D., Jiang, K., Weber-Levine, C. et al. Spinal cord vascular autoregulation: key concepts and opportunities to improve management. Spinal Cord 64, 14–28 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-025-01126-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-025-01126-5