Abstract

Study design

Retrospective chart review.

Objectives

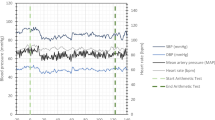

The primary aim was to identify the number of patients requiring vasopressors beyond the first week of cervical spinal cord injury (SCI). Secondary objectives were to note the type, duration and doses of vasopressors and any association between prolonged vasopressors use and outcome.

Setting

Neurosurgical intensive care of a tertiary trauma care centre.

Methods

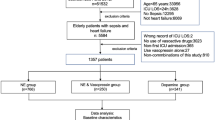

After Ethical approval we retrospectively collected the data of patients of isolated cervical SCI admitted to neurosurgical intensive care from January to December 2017. Vasopressor requirement for sepsis or cardiac arrest was excluded.

Results

Out of 80 patients analysed, 54 (67.5%) received vasopressors. The prolonged requirement of vasopressors was observed in 77.7%. Our preferred agent was dopamine (64.8%). We found out that longer requirement (in days) of high dose of dopamine was associated with higher survival (p = 0.03).

Conclusion

Our results describe a significant portion of cervical SCI patients need ongoing vasopressor to maintain a mean arterial pressure >65 mm of Hg beyond first week. We observed patients who required longer duration of high dose dopamine had a higher chance of survival suggesting some unknown mechanism of high dose of dopamine. This is first such observation, further studies are needed to substantiate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Singh A, Tetreault L, Kalsi-Ryan S, Nouri A, Fehlings MG. Global prevalence and incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:309–31.

Fielingsdorf K, Dunn RN. Cervical spine injury outcome-a review of 101 cases treated in a tertiary referral unit. S Afr Med J. 2007;97:203–7.

Ploumis A, Yadlapalli N, Fehlings MG, Kwon BK, Vaccaro AR. A systematic review of the evidence supporting a role for vasopressor support in acute SCI. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:356–62.

Walters BC, Hadley MN, Hurlbert RJ, Aarabi B, Dhall SS, Gelb DE, et al. Guidelines for the management of acute cervical spine and spinal cord injuries: 2013 update. Neurosurgery. 2013;60:82–91.

Saadeh YS, Smith BW, Joseph JR, Jaffer SY, Buckingham MJ, Oppenlander ME, et al. The impact of blood pressure management after spinal cord injury: a systematic review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;43:E20.

Ashta KK, Kumar R. Prevalence of resting bradycardia, resting hypotension and orthostatic hypotension in chronic spinal cord injury patients. Int J Adv Med. 2017;4:1319–122.

Claydon VE, Steeves JD. Orthostatic hypertension following spinal cord injury: understanding clinical pathophysiology. Spinal Cord. 2006;44:341–35.

Grigorean VT, Sandu AM, Popescu M, Iacobini MA, Stoian R, Neascu C, et al. Cardiac dysfunctions following spinal cord injury. J Med Life. 2009;2:133–45.

Krassioukov A, Eng JJ, Warburton DE, Teasell R. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence Research Team. A systematic review of the management of orthostatic hypotension after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:876–85.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A, et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:535–46.

King JE. What is “renal dose” dopamine? Nursing 2004;34:26.

Bassi E, Park M, Azevedo LC. Therapeutic strategies for high-dose vasopressor-dependent shock. Crit Care Res Pr. 2013;2013:654708.

Shao J, Zhu W, Chen X, Jia L, Song D, Zhou X, et al. Factors associated with early mortality after cervical spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:555–562.

Lehmann KG, Lane JG, Piepmeier JM, Batsford WP. Cardiovascular abnormalities accompanying acute spinal cord injury in humans: incidence, time course and severity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;10:46–52.

Inoue T, Manley GT, Patel N, Whetstone WD. Medical and surgical management after spinal cord injury: vasopressor usage, early surgerys, and complications. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31:284–91.

Walters BC, Hadley MN, Hurlbert RJ, Aarabi B, Dhall SS, Gelb DE, et al. American Association of Neurological Surgeons; Congress of Neurological Surgeons. Guidelines for the management of acute cervical spine and spinal cord injuries: 2013 update. Neurosurgery. 2013;60:82–91.

Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Early acute management in adults with spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals. J Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31:403–479.

Catapano JS, John Hawryluk GW, Whetstone W, Saigal R, Ferguson A, Talbott J, et al. Higher Mean Arterial Pressure Values Correlate with Neurologic Improvement in Patients with Initially Complete Spinal Cord Injuries. World Neurosurg. 2016;96:72–9.

Glick DB: The Autonomic Nervous System. In miller RD, editor. Miller’s Anesthesia, ed 8. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2015. p. 367.

Bilello JF, Davis JW, Cunningham MA, Groom TF, Lemaster D, Sue LP. Cervicalspinal cord injury and the need for cardiovascular intervention. Arch Surg. 2003;138:1127–9.

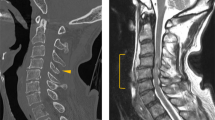

Kurpad S, Martin AR, Tetreault LA, Fischer DJ, Skelly AC, Mikulis D, et al. Impact of Baseline Magnetic Resonance Imaging on Neurologic, Functional, and Safety Outcomes in Patients With Acute Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Glob Spine J 2017;7:151S–174S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mishra, R.K., Goyal, K., Bindra, A. et al. An investigation to the prolonged requirement (>7 days) of vasopressors in cervical spinal cord injury patients—a retrospective analysis. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 7, 96 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-021-00459-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-021-00459-6