Abstract

The small, hormone-like molecule retinoic acid (RA) is a vital regulator in several neurobiological processes that are affected in depression. Next to its involvement in dopaminergic signal transduction, neuroinflammation, and neuroendocrine regulation, recent studies highlight the role of RA in homeostatic synaptic plasticity and its link to neuropsychiatric disorders. Furthermore, experimental studies and epidemiological evidence point to the dysregulation of retinoid homeostasis in depression. Based on this evidence, the present study investigated the putative link between retinoid homeostasis and depression in a cohort of 109 patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and healthy controls. Retinoid homeostasis was defined by several parameters. Serum concentrations of the biologically most active Vitamin A metabolite, all-trans RA (at-RA), and its precursor retinol (ROL) were quantified and the individual in vitro at-RA synthesis and degradation activity was assessed in microsomes of peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells (PBMC). Additionally, the mRNA expression of enzymes relevant to retinoid signaling, transport, and metabolism were assessed. Patients with MDD had significantly higher ROL serum levels and greater at-RA synthesis activity than healthy controls providing evidence of altered retinoid homeostasis in MDD. Furthermore, MDD-associated alterations in retinoid homeostasis differed between men and women. This study is the first to investigate peripheral retinoid homeostasis in a well-matched cohort of MDD patients and healthy controls, complementing a wealth of preclinical and epidemiological findings that point to a central role of the retinoid system in depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is a complex and debilitating disorder affecting roughly 300 million people worldwide and exacting huge tolls on individuals and societies [1]. Given the multifactorial etiology and heterogeneous phenotypic expressions of the disorder, there is a vast number of concepts on depression pathophysiology. Alterations in major neurobiological processes such as monoamine neurotransmission, neuroendocrine regulation, inflammatory processes, and particularly multiple forms of cellular and synaptic plasticity have been described for depression [2, 3]. Accordingly, several targeted treatments have been developed, mainly targeting the level of monoaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission. However, despite tremendous progress in elucidating neurobiological correlates, the final, individual, and possibly patient-specific molecular mechanisms and their reciprocal interactions are still incompletely understood [4, 5]. Modulating effects on neural plasticity at levels beyond direct neurotransmitter actions have recently been described for the hormone-like small molecule retinoic acid (RA) [6].

RA—the active metabolite of vitamin A (retinol, ROL)—is a highly potent neural regulator that acts in an auto- and paracrine manner and is involved in a range of brain physiological processes. While RA has previously mostly been considered in the context of embryonic and early postnatal development, its important role in the healthy functioning of the adult brain is now well established [7]. Studies investigating its molecular actions revealed a remarkable involvement of RA in essential neurobiological pathways that are also affected in neuropsychiatric disorders. For example, RA was shown to be a crucial component in the signal transduction pathways of dopaminergic and neuropeptide signaling, neuroinflammation, and hypothalamic neuroendocrine regulation [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Furthermore, several aspects of neuronal plasticity such as neurite outgrowth, neurogenesis, and Hebbian forms of synaptic plasticity rely on RA signaling [14,15,16,17]. Strikingly, RA also functions as a critical regulator during homeostatic synaptic plasticity which is a non-Hebbian form of plasticity and serves as a mechanism of metaplasticity to maintain network stability [6, 18,19,20].

Several lines of evidence link RA to depression. Most recently, Suzuki and colleagues [21] could show that the inactivity-dependent up-regulation of synaptic efficacy mediated through RA has a rapid, antidepressant-like effect in mice similar to the antidepressant effects of ketamine. A study by Mulvey and Dougherty [22] suggests that major depressive disorder (MDD) -associated functional single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) share a transcription regulation system that is activated by retinoid transcription factors and thus highly responsive to regulation through RA. Post-mortem studies could show that RA signaling, transport, and metabolism machinery is expressed in the adult hippocampus, hypothalamus, and prefrontal cortex [23,24,25,26] and that mRNA expression profiles differ between patients with mood disorders and control subjects [27, 28]. Last but not least, a causal link between dysregulation in RA homeostasis and depression is suggested by findings on the depressogenic effects of exogenous RA—as often seen in dermatological treatment with systemic retinoids [29].

Endogenous retinoid levels in neuropsychiatric disorders have thus far only been investigated by a few studies. Yang et al. [30], in their prospective study, identified reduced RA serum levels as a risk factor for the development of post-stroke depression at three months. Guo et al. [31] found reduced retinol levels in children with autism and meta-analytical evidence suggests RA dysregulation in Alzheimer’s [32]. In our previous work, we identified reduced levels of RA and retinol as well as a dysregulation of retinoid homeostasis-associated genes in patients with schizophrenia [33].

The present study is the first to investigate endogenous retinoid homeostasis parameters in a cohort of well-defined patients with MDD and matched healthy controls. Based on previous evidence, we hypothesized that retinoid homeostasis would be altered in MDD patients as compared to controls. We assessed retinoid homeostasis through several parameters. Serum levels of the biologically most active RA isomer, all-trans retinoic acid (at-RA), and its precursor ROL were analyzed and the functional signaling activity of serum RA was assessed via reporter cell assays. The individual in vitro at-RA metabolism activity was assessed in peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells (PBMC). Additionally, we assessed mRNA expression profiles of several RA homeostasis-related genes such as proteins involved in retinoid transport, signal transduction, and select enzymes essentially involved in local at-RA synthesis and degradation.

Methods and materials

Participants

Patients with MDD from our in- and outpatient units and healthy control subjects matched for age, BMI, and smoking status were recruited for the clinical observational study on RA homeostasis in neuropsychiatric disorders (RAHND; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02439099) between 2015 and 2019. All patients received standard care treatment, had a specialist-confirmed ICD 10 diagnosis of moderate or severe depression, and did not currently receive psychotropic medication. Participants who showed any clinical signs of acute inflammation were treated with retinoids or anti-inflammatory medication or had a diagnosed neurological, somatic, or additional severe psychiatric disorder were excluded. All participants were thoroughly informed and gave their written consent. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (EA4/002/13).

Blood samples

Samples of peripheral venous blood were obtained during a routine blood draw at admission for serum analysis of retinoid levels and isolation of PBMC. All samples were collected in a standardized manner before noon. There were no restrictions on prior meal intake. Serum aliquots were stored at −80 °C until further analysis. PBMC were isolated from heparinized blood by the FICOLLTM density gradient centrifugation, according to previously established protocols [34].

Extraction of retinoids from serum

Retinoids were extracted from sera using a liquid-liquid extraction protocol. To avoid photoisomerization, all experiments were carried out under dim red light. Serum samples were spiked with the synthetic retinoid all-trans acitretin as an internal standard (FC 1 µM) to assess recovery and account for inter-assay variability and to calculate final retinoid serum concentrations. Acidified ethanol and 2 vol hexane were added to 1 vol of serum. Samples were vortex mixed, shaken for 15 min, and then centrifuged at 4 °C, 1560×g for 5 min. The organic phase was carefully transferred into glass tubes and evaporated to dryness under a stream of argon. The same extraction procedures were applied to standard solutions for the determination of matrix effects. Dried extracts were reconstituted in HPLC eluent and centrifuged for 5 min at 21,000×g at 4 °C. An aliquot of 100 µl was injected into the HPLC system.

Preparation of crude microsomal fractions for RA metabolism assays

PBMC is a widely used model to study person-specific cell dynamics and is increasingly used as a source of biomarkers for diagnostics and prediction [35,36,37]. The crude microsomal fractions derived from the individual PBMC contain metabolic enzymes like CYPs that are involved in the turnover of drugs or endogenous substrates such as retinoids and are thus often used to study metabolic pathways. Metabolically active crude microsomal fractions were prepared in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline without Mg++ and Ca++ (pH 7.3; Gibco, Thermo Fischer) from participants’ PBMC by homogenization and differential centrifugation steps according to previously published protocols [33]. Protein concentration was determined with the BCA method (Thermo Fischer, USA) and microsomal fractions were stored at −80 °C. To determine individual RA metabolic activity, in vitro assays containing the RA-metabolizing microsomal preparations from participants’ cells were performed according to previously published protocols with minor adjustments [38]. In brief, heat-inactivated controls and metabolically active reactions contained microsomal preparations at a protein concentration of 250 µg/ml. For RA synthesis assays, ROL (FC 100 µM) and NADP+ were added to the reaction. at-RA (FC 2 µM) and NADPH Regeneration System (NRS; Promega, USA) were added for RA catabolism assays. After an incubation period of 60 min at 37 °C, the reaction was stopped by adding 4vol ice-cold methanol. Samples were then centrifuged at 21,000×g at 4 °C and subjected to HPLC retinoid analysis. at-RA synthesis or degradation was quantified by comparing metabolically active samples with heat-inactivated controls.

High-performance liquid chromatography

Retinoid analysis was performed on a reverse-phase Agilent 1100 HPLC system equipped with a binary pump, temperature-controlled column compartment, auto-sampler, and a high-sensitivity diode array detector (DAD). Separation was achieved using a Phenomenex Synergi™ 4 µm Hydro-RP 80 A (250 mm × 4.6 mm) column at room temperature. The mobile phase consisted of H2O + 0.1% formic acid (eluent A) and acetonitrile + 0.1% formic acid (eluent B). For serum analysis, a combination of isocratic and gradient elution was used as described in Table 1 of the Supplement. At a constant flow rate of 1.7 ml/min, the total runtime was 24 min for one sample. This setup allowed for excellent resolution of retinal, ROL, RA isomers, and oxidation products (Supplementary Fig. 1). In a single HPLC run, several compounds could be clearly separated in serum, with a retention time of 5.1 min for the internal standard acitretin, 9.3 min for at-RA, and 10.9 min for ROL (Supplementary Fig. 2). All peaks and retention times were confirmed by authentic standards of the retinoid isomers (Sigmar Aldrich). For the quantification of retinoids in the metabolism assays, isocratic elution (15% A: 85 % B) was used with a total run time of 13 min per sample.

Real-time PCR for relative expression of retinoid-relevant genes

mRNA expression of relevant RA-homeostasis genes in PBMC was assessed by real-time PCR. RNA was extracted using Direct-zol DNA/RNA Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research) as per the manufacturer’s instructions and the sample quality was checked afterward using Nanodrop Instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., MA, USA). Total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., MA, USA) and stored at −20 °C until further measurement. Relative quantification (ΔCt) and melting curve analysis were both carried out using the StepOne™ Real-Time PCR System software. All primers were designed and checked for their quality using the Primer-BLAST software [39]. The sequences of primers are shown in Table 2 of the supplement. The expression fold change from the target to endogenous reference genes was calculated as 2-ΔCt as suggested for presenting individual data points [40]. The values were log-transformed for statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses, power, and sample size calculations

Group differences were examined using chi-squared tests or independent samples t-tests depending on the level of measurement. Effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d. Linear regression was used for the analysis of the relationship between retinoid serum levels and reporter assay activity. Interaction effects were tested with a two-way ANOVA. Sample size and power calculations were performed expecting minimum group differences in serum RA levels based on previously published data comparing RA serum levels in different cohorts [41]. With an even sampling ratio, a power of 95%, and α = 0.01, a total of 47 participants per group were needed to detect putative group differences. Data analyses were carried out with IBM SPSS version 25. GraphPad Prism version 9 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for data visualization.

Results

Participants

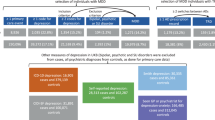

In total, 116 participants were recruited for the study. Seven participants (MDD = 6, HC = 1) had to be excluded due to emerging somatic or psychiatric disorders, or previously undocumented intake of psychotropic medication. Thus, 58 MDD patients and 58 healthy controls (61.2% female) were included in the study. The two groups did not differ in age, gender, or smoking status. Further demographic data and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. HDL cholesterol and Vitamin D3 25(OH) were higher in healthy controls compared to MDD patients. Triglyceride levels correlated significantly positively with at-RA (r = 0.597, p = 0.000) and ROL (r = 0.532, p = 0.000) levels while HDL levels showed a significant negative association with at-RA (r = −0.377, p = 0.000) and ROL levels (r = −0.356, p = 0.001).

Retinoid serum levels

at-RA and ROL serum levels were quantified by HPLC in 57 unmedicated clinically depressed patients and 52 healthy control participants. The ratios of at-RA to ROL were calculated. at-RA levels ranged from 0.73 nM to 6.3 nM with a mean of 2.8 nM (SD: ±1.17) and ROL levels ranged between 0.16 µM to 3.08 µM with an average of 1.1 µM (SD: ±0.61). Neither at-RA nor ROL serum levels showed a correlation with age, BMI, current smoking status, or level of education.

Altered retinol serum levels in patients with depression

ROL levels were significantly higher in patients as compared to healthy controls (t = 2.63, p = 0.01, d = 0.5). at-RA levels were also higher in patients but the group difference was not significant. Moreover, the individually calculated at-RA/ROL ratio was significantly reduced in the patient group (t = −2.06, p = 0.042, d = −0.4) (Fig. 1A–C).

Increased at-RA synthesis in patients with depression

To capture possible differences in retinoid metabolism, we assessed the individual in vitro at-RA synthesis and degradation activity in metabolically active PBMC-derived crude microsomal fractions. at-RA synthesis and degradation activity were assessed in standardized reactions normalized by heat-inactivated controls. The at-RA-synthesizing activity was significantly greater in the patient group than in the group of healthy controls (t = 3.022, p = 0.003, d = 0.6) (Fig. 1D). Composite scores of ROL*atRA-synthesis and RA*atRA-catabolism were built to obtain a measure of the individual homeostatic “in-“ and “out”-flow, respectively. As expected, differences in group mean of retinoid serum levels and metabolism activity was also reflected in the individual composite scores, showing a significantly increased homeostatic “in-flow” in patients as compared to healthy controls (t = 3.139, p = 0.002, d = 0.6).

Expression of retinoid-relevant genes

No overall group differences were found for any of the targets.

Gender differences in retinoid homeostasis parameters

In the patient group as well as in the control group, retinoid serum levels were significantly different in men and women. These findings together with evidence from the literature on gender differences in depression prompted us to examine group differences within gender for all retinoid homeostasis parameters. Gender differences within the group of healthy controls are also reported.

For serum ROL levels, we found significant group differences between patients and controls for the male gender only (t = 2.915, p = 0.006, d = 0.9) (Fig. 2A, B). ROL levels in women did not differ between groups. Interaction effects of group × gender were not significant.

* marks significant within-group gender differences (i.e., male vs female in MDD or HC). ▲ marks significant group differences for within-gender comparisons (i.e., female MDD vs female HC) A ROL serum levels. B at-RA serum levels. C the ratio of at-RA to ROL. D at-RA synthesis activity in PBMC. E–H Gene transcription of retinoid pathway-related genes in PBMC, fold change values presented as the 2−ΔCt. Error bars depict the median (A–D) or geometric mean (E–H) with 95% CI. t-tests were used for group comparisons.

Synthesis activity in female MDD patients was significantly higher than in female controls (t = 3.072, p = 0.004, d = 0.8) (Fig. 2D). No such difference was found for the male gender. No significant group or gender differences were observed for RA-catabolism activity.

Differences in mRNA expression of retinoid homeostasis-relevant genes between patients and healthy controls were found only for the female gender, showing higher expression of cellular retinol-binding protein 1 (CRBP1), retinol dehydrogenase 10 (RDH10) and CYP2C19 and reduced expression of retinoic acid receptor γ (RARg) in female patients compared to female controls (Fig. 2E–H).

Within the group of healthy controls, we found gender differences in mRNA expression of CRBP1 and serum levels of at-RA and ROL. CRBP1 was increased in men compared to women (Fig. 2G) and at-RA and ROL levels were significantly higher in men than in women (Fig. 2A, B).

Discussion

In this well-matched cohort of unmedicated patients and healthy controls, we could show for the first time that important features of peripherally assessed retinoid homeostasis, which is a key player in regulating synaptic plasticity in the central nervous system, are altered in patients with MDD. Significantly increased ROL serum levels and at-RA synthesis activity in depressed patients highlights a possible pathophysiological contribution of altered retinoid homeostasis.

In our own previous work on retinoid homeostasis in patients with schizophrenia, we found reduced ROL and at-RA levels in patients compared to controls, as well as strong effects of the atypical antipsychotic clozapine on at-RA levels [33]. A study by Yang et al. [30] identified reduced RA serum levels as a risk factor for the development of post-stroke depression. Both studies report a dysbalance in retinoid serum levels or metabolism activity in psychiatric patients as compared to controls, and both studies suggest a protective role of endogenous RA. Further evidence of endogenous RA in disease stems from the somatic field. Similarly, higher at-RA serum levels are linked to more beneficial disease outcomes for cardiovascular disease, neurological syndromes, and cancer [42,43,44,45]. A recent prospective study of 29,104 men reports reduced overall and cause-specific mortality for participants with higher ROL serum levels during a 30-year follow-up [46]. In many of the disorders investigated, increased inflammation plays a central role in the onset and disease progression. The attenuating effect of RA in these cases can be explained by its strong anti-inflammatory properties [11, 47]. Many somatic disorders are closely associated with depression by way of shared biological, social, or psychological disease pathways [48], however, retinoid homeostasis in depression has thus far not been investigated.

Interestingly, in the present study, retinoid serum levels and at-RA synthesis activity were increased in patients compared to controls. Especially as patients did not currently receive psychotropic medication, the statistically significant differences between patients and controls are suggested to be the result of homeostatic adaptions of the endogenous retinoid signaling system in patients with MDD. Although the meaning, direction, and extent of such adaptive processes are certainly incompletely understood, there is further evidence supporting the hypothesis of a compensatory, adaptive change within the homeostatically regulated system. at-RA is an important regulator and necessary for the normal functioning of a range of neurobiological processes that are implicated in depression [49]. Greater demand for at-RA would be reflected in increased peripheral bioavailability of its substrate ROL and increased at-RA synthesis activity as shown in our data (Fig. 1A, C). In the example of disturbed homeostatic synaptic plasticity, RA is produced upon chronic synaptic inactivity, to effect translational upregulation of postsynaptic glutamate receptors, leading to an upregulation of synaptic strength [6, 21]. Engaging the processes of homeostatic synaptic plasticity has also been proposed as a treatment option for MDD [3].

Throughout the analyses of the homeostasis parameters, we saw striking effects of gender. Within the group of healthy controls, at-RA and ROL levels were higher in men than in women, which is in line with previous findings for ROL [50]. The expression of CRBP1, which facilitates cellular uptake of serum ROL and delivers ROL intracellularly to select metabolic enzymes, was also increased in men compared to women. However, in vitro synthesis or catabolism activity did not differ between men and women. Based on our findings of gender differences in retinoid serum levels, and evidence suggesting that psychological and biological aspects of depression differ for men and women [51,52,53], we chose to also run within-gender comparisons of patients and controls in a secondary analysis. ROL serum levels were starkly increased in male depressed patients as compared to male controls while ROL serum levels did not differ between female patients and controls (Fig. 2A). Although other factors that we did not assess and control for might be at play, increased ROL serum levels might represent a male endophenotype of depression—or male-specific compensatory action.

The in vitro metabolism assays showed greater at-RA synthesis in female MDD patients than in female healthy controls (Fig. 2D). Though circumstantial and warranting further investigation, this dynamic is partially mirrored across levels of analysis in our data on mRNA expression patterns of genes relevant to RA synthesis (Fig. 2E–H). CRBP1, RDH10—one of the enzymes involved in the first of the two-step oxidation from ROL to at-RA—and one of the RA catabolizing enzymes, CYP2C19, were increased in female MDD patients compared to female controls, suggesting increased turnover of both at-RA and its substrate ROL. While CYP2C19 activity in at-RA breakdown is relatively low, it is interesting to note that it is also involved in the pharmacokinetics of psychotropic drugs. Fluoxetine, a major serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), potently blocks RA catabolism by inhibiting CYP2C19 activity [54, 55]. Gender differences in the pharmacokinetics and antidepressant response to SSRIs have been described [56, 57].

Taken together, we see different manifestations of altered retinoid homeostasis for men and women. While ROL serum levels were affected in male patients, retinoid metabolism was altered for female MDD patients. Gender differences and sex-specific retinoid dynamics in adult humans are scarcely discussed in the literature. Some support for gender differences in retinoid homeostasis comes from preclinical studies showing sex-specific expression patterns of retinoid receptors, heterogeneous retinol distribution across the brain areas of males and females, and strong effects of sex hormones on RA activities [58,59,60].

Based on previous studies on the central role of the retinoid system for depression, we sought to elucidate a putative dysregulation of retinoid homeostasis in MDD by systematically assessing various aspects of retinoid homeostasis in unmedicated patients and healthy controls. A dysbalance in homeostasis may become apparent at any one point of the transport, binding, and metabolism activities. By assessing several parameters that govern retinoid flux and determining at-RA availability, we obtained a broad picture of peripheral retinoid homeostasis. As psychotropic medication can influence RA metabolism [33] and the retinoid signaling system is also linked to other psychiatric, neurological, and somatic disorders, we selected patients who did not currently take any psychotropic medication and did not have major psychiatric, neurological, or somatic comorbidities. This allowed us to investigate the MDD—retinoid associations in a “raw state”. However, the MDD population without somatic or psychiatric comorbidities only represents a part of the MDD spectrum, possibly limiting the generalizability of our findings to a subgroup of MDD patients. For some group comparisons, the differences reported are rather small, yet statistically significant. Whether they are of clinical relevance remains to be investigated as there is currently no definition of minimally clinically important differences for these retinoid parameters in an MDD cohort. However, as this is an exploratory study, we chose to report even small differences between groups, as they may help to clarify the hypothesis of the involvement of retinoids in depression. Furthermore, the cohort was not originally powered to investigate gender differences. The gender distribution in this study mirrors the gender distribution of MDD in the general population, however, the sample size of male participants may have been too small to detect subtle group differences in mRNA expression or metabolism activity. Taking gender into account, future studies should assess retinoid homeostasis longitudinally to investigate the effects of treatment and compare homeostasis parameters in remitted patients to healthy controls. In addition, exploring the relationship between cholesterol and the retinoid system in depression might be an interesting avenue for future research. Given that RA is involved in lipid metabolism [61, 62], our results on significantly lower HDL levels in MDD patients, and the strong correlation of triglyceride and HDL levels with retinoid serum levels provide preliminary insights that should be evaluated further.

In conclusion, next to group differences in ROL serum levels and at-RA synthesis activity, our data suggest that MDD-associated alterations in retinoid homeostasis differ between men and women. Relations among the different homeostasis parameters as well as their relation to depression pathophysiology are highly intricate. Our study was not designed to mechanistically assess these relations. Instead, we cross-sectionally assessed several homeostasis parameters which can serve as a demonstration that investigating retinoid signaling as a putative pathophysiological mechanism of depression might be worthwhile for achieving a better understanding of the disease’s underlying neuropathophysiology.

References

Bloom DE, Cafiero E, Jané-Llopis E, Abrahams-Gessel S, Bloom LR, Fathima S, et al. The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases. 2011;(September). Available from: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Harvard_HE_GlobalEconomicBurdenNonCommunicableDiseases_2011.pdf.

Krishnan V, Nestler EJ. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature 2008;455:894–902.

Workman ER, Niere F, Raab-Graham KF. Engaging homeostatic plasticity to treat depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:26–35.

Dean J, Keshavan M. The neurobiology of depression: an integrated review. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;27:101–11.

Otte C, Gold SM, Penninx BW, Pariante CM, Etkin A, Fava M, et al. Major depressive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2016;2:1–20.

Aoto J, Nam CI, Poon MM, Ting P, Chen L. Synaptic signaling by all-trans retinoic acid in homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Neuron 2008;60:308–20.

Lane MA, Bailey SJ. Role of retinoid signalling in the adult brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;75:275–93.

Samad TA, Krezel W, Chambon P, Borrelli E. Regulation of dopaminergic pathways by retinoids: activation of the D2 receptor promoter by members of the retinoic acid receptor-retinoid X receptor family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14349–54.

Richard S, Zingg HH. Identification of a retinoic acid response element in the human oxytocin promoter. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21428–33.

Kim JH, Yu KS, Jeong JH, Lee NS, Lee JH, Jeong YG, et al. All-trans-retinoic acid rescues neurons after global ischemia by attenuating neuroinflammatory reactions. Neurochem Res. 2013;38:2604–15.

Clemens V, Regen F, Le Bret N, Heuser I, Hellmann-Regen J. Anti-inflammatory effects of minocycline are mediated by retinoid signaling. BMC Neurosci. 2018;19:1–10.

Cai L, Li R, Zhou JN. Chronic all-trans retinoic acid administration induces CRF over-expression accompanied by AVP up-regulation and multiple CRF-controlling receptors disturbance in the hypothalamus of rats. Brain Res. 2015;1601:1–7.

Imoesi PI, Bowman EE, Stoney PN, Matz S, McCaffery P. Rapid action of retinoic acid on the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12(October):1–8.

Corcoran J, Maden M. Nerve growth factor acts via retinoic acid synthesis to stimulate neurite outgrowth. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:307–8.

Takahashi J, Palmer TD, Gage FH. Retinoic acid and neurotrophins collaborate to regulate neurogenesis in adult-derived neural stem cell cultures. J Neurobiol. 1999;38:65–81.

Jacobs S, Lie DC, DeCicco KL, Shi Y, DeLuca LM, Gage FH, et al. Retinoic acid is required early during adult neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3902–7.

Chiang MY, Misner D, Kempermann G, Schikorski T, Giguère V, Sucov HM, et al. An essential role for retinoid receptors RARbeta and RXRgamma in long-term potentiation and depression. Neuron 1998;21:1353–61.

Chen L, Lau AG, Sarti F. Synaptic retinoic acid signaling and homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Neuropharmacology 2014;78:3–12.

Hsu YT, Li J, Wu D, Südhof TC, Chen L. Synaptic retinoic acid receptor signaling mediates mTOR-dependent metaplasticity that controls hippocampal learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:7113–22.

Zhang Z, Marro SG, Zhang Y, Arendt KL, Patzke C, Zhou B, et al. The fragile X mutation impairs homeostatic plasticity in human neurons by blocking synaptic retinoic acid signaling. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:1–16.

Suzuki K, Kim JW, Nosyreva E, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. Convergence of distinct signaling pathways on synaptic scaling to trigger rapid antidepressant action. Cell Rep. 2021;37:1–13.

Mulvey B, Dougherty JD. Transcriptional-Regulatory Convergence Across Functional MDD Risk Variants Identified by Massively Parallel Reporter Assays. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:1–13.

Fragoso YD, Shearer KD, Sementilli A, de Carvalho LV, McCaffery PJ. High expression of retinoic acid receptors and synthetic enzymes in the human hippocampus. Brain Struct Funct. 2012;217:473–83.

Meng QY, Chen XN, Zhao J, Swaab DF, Zhou JN. Distribution of retinoic acid receptor-α immunoreactivity in the human hypothalamus. Neuroscience 2011;174:132–42.

Stoney PN, Fragoso YD, Saeed RB, Ashton A, Goodman T, Simons C, et al. Expression of the retinoic acid catabolic enzyme CYP26B1 in the human brain to maintain signaling homeostasis. Brain Struct Funct. 2016;221:3315–26.

Haybaeck J, Postruznik M, Miller CL, Dulay JR, Llenos IC, Weis S. Increased expression of retinoic acid-induced gene 1 in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:279–89.

Qi XR, Zhao J, Liu J, Fang H, Swaab DF, Zhou JN. Abnormal retinoid and TrkB signaling in the prefrontal cortex in mood disorders. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25:75–83.

Chen XN, Meng QY, Bao AM, Swaab DF, Wang GH, Zhou JN. The involvement of retinoic acid receptor-α in corticotropin-releasing hormone gene expression and affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:832–9.

Bremner JD, Shaerer K, McCaffery P. Retinoic acid and affective disorders: the evidence for an association. Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:37–50.

Yang CD, Cheng ML, Liu W, et al. Association of serum retinoic acid with depression in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12:2647–58.

Guo M, Zhu J, Yang T, Lai X, Liu X, Liu J, et al. Vitamin A improves the symptoms of autism spectrum disorders and decreases 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT): A pilot study. Brain Res Bull. 2018 Mar;137:35–40.

Lopes Da Silva S, Vellas B, Elemans S, Luchsinger J, Kamphuis P, Yaffe K, et al. Plasma nutrient status of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014;10:485–502.

Regen F, Cosma NC, Otto LR, Clemens V, Saksone L, Gellrich J, et al. Clozapine modulates retinoid homeostasis in human brain and normalizes serum retinoic acid deficit in patients with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;26:5417–28.

Regen F, Herzog I, Hahn E, Ruehl C, Le Bret N, Dettling M, et al. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis: Evidence for an immune-mediated mechanism from a patient-specific in-vitro approach. Toxicol Appl Pharm. 2017;316:10–6.

Cosma NC, Üsekes B, Otto LR, Gerike S, Heuser I, Regen F, et al. M1/M2 polarization in major depressive disorder: Disentangling state from trait effects in an individualized cell-culture-based approach. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;94:185–95.

Hellmann-Regen J, Spitzer C, Kuehl LK, Schultebraucks K. Altered cellular immune reactivity in traumatized women with and without major depressive disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019;101(July 2018):1–6.

Zaki JK, Lago SG, Rustogi N, Gangadin SS, Benacek J, van Rees GF, et al. Diagnostic model development for schizophrenia based on peripheral blood mononuclear cell subtype-specific expression of metabolic markers. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:1–10.

Regen F, Le Bret N, Hildebrand M, Herzog I, Heuser I, Hellmann-Regen J. Inhibition of brain retinoic acid catabolism: a mechanism for minocycline’s pleiotropic actions? World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17:634–40.

Ye J, Coulouris G, Zaretskaya I, Cutcutache I, Rozen S, Madden TL. Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinforma. 2012;13:134.

Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–8.

Fex G, Andersson M, Berggren-Söderlund M. Low serum concentration of all-trans and 13.cis retinoic acids in patients treated with phenlrloin, carbamazepine and valproate. Possible relation to teratogenicity. Arch Toxicol. 1995;69:572–4.

Liu Y, Chen H, Mu D, Li D, Zhong Y, Jiang N, et al. Association of serum retinoic acid with risk of mortality in patients with coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2016;119:557–63.

Libien J, Kupersmith MJ, Blaner W, McDermott MP, Gao S, Liu Y, et al. Role of vitamin A metabolism in IIH: results from the idiopathic intracranial hypertension treatment trial. J Neurol Sci. 2017;372:78–84.

Tu WJ, Qiu HC, Zhang Y, Cao JL, Wang H, Zhao JZ, et al. Lower serum retinoic acid level for prediction of higher risk of mortality in ischemic stroke. Neurology 2019;92:E1678–87.

Moulas AN, Gerogianni IC, Papadopoulos D, Gourgoulianis KI. Serum retinoic acid, retinol and retinyl palmitate levels in patients with lung cancer. Respirology 2006;11:169–74.

Huang J, Weinstein SJ, Yu K, Männistö S, Albanes D. Association between serum retinol and overall and cause-specific mortality in a 30-year prospective cohort study. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1–11.

Katsuki H, Kurimoto E, Takemori S, Kurauchi Y, Hisatsune A, Isohama Y, et al. Retinoic acid receptor stimulation protects midbrain dopaminergic neurons from inflammatory degeneration via BDNF-mediated signaling. J Neurochem. 2009;110:707–18.

Gold SM, Köhler-Forsberg O, Moss-Morris R, Mehnert A, Miranda JJ, Bullinger M, et al. Comorbid depression in medical diseases. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2020;6:1–22.

Wołoszynowska-Fraser MU, Kouchmeshky A, McCaffery P. Vitamin A and retinoic acid in cognition and cognitive disease. Annu Rev Nutr. 2020;40:247–72.

Olmedilla B, Granado F, Blanco I, Rojas-Hidalgo E. Seasonal and sex-related variations in six serum carotenoids, retinol, and α-tocopherol. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:106–10.

Mei L, Wang Y, Liu C, Mou J, Yuan Y, Qiu L, et al. Study of sex differences in unmedicated patients with major depressive disorder by using resting state brain functional magnetic resonance imaging. Front Neurosci. 2022;16(March):1–7.

Schneider L, Walther A. Geschlechtsunterschiede in glucocorticoidkonzentrationen und entzündungsparametern im zusammenhang mit depression. Nervenheilkunde. 2020;39:222–37.

Young E, Korszun A. Sex, trauma, stress hormones and depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:23–8.

Harvey AT, Preskorn SH. Fluoxetine pharmacokinetics and effect on CYP2C19 in young and elderly volunteers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:161–6.

Hellmann-Regen J, Uhlemann R, Regen F, Heuser I, Otte C, Endres M, et al. Direct inhibition of retinoic acid catabolism by fluoxetine. J Neural Transm. 2015;122:1329–38.

Khan A, Brodhead AE, Schwartz KA, Kolts RL, Brown WA. Sex differences in antidepressant response in recent antidepressant clinical trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:318–24.

Sramek JJ, Murphy MF, Cutler NR. Sex differences in the psychopharmacological treatment of depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016;18:447–57.

Arfaoui A, Lobo MVT, Boulbaroud S, Ouichou A, Mesfioui A, Arenas MI. Expression of retinoic acid receptors and retinoid X receptors in normal and vitamin A deficient adult rat brain. Ann Anat. 2013;195:111–21.

Arfaoui A, Nasri I, Boulbaroud S, Ouichou A, Mesfioui A. Effect of vitamin A deficiency on retinol and retinyl esters contents in rat brain. Pak J Biol Sci. 2009;12:939–48.

Napoli JL. Retinoic acid: sexually dimorphic, anti-insulin and concentration-dependent effects on energy. Nutrients. 2022;14:1–22.

Schoonjans K, Staels B, Auwerx J. Role of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) in mediating the effects of fibrates and fatty acids on gene expression. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:907–25.

Kiefer FW, Vernochet C, O’Brien P, Spoerl S, Brown JD, Nallamshetty S, et al. Retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 1 regulates a thermogenic program in white adipose tissue. Nat Med. 2012;18:918–25.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LRO: data acquisition, data preparation, statistical analyses, interpretation of data, and writing of the first and final drafts of the paper. VC: data acquisition, interpretation of results, critical revision of the first draft of the paper, approval of the final version of the manuscript. BÜ: analyses and interpretation of PCR data, critical revision of the first draft of the paper, approval of the final version of the paper. NCC: data acquisition, critical revision of the first draft of the paper, approval of the final version of the paper. FR: interpretation of data, critical revision of the first draft of the paper, approval of the final version of the paper. JHR: conception and study design, interpretation of data, critical revision of the first draft of the paper, approval of the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Otto, L.R., Clemens, V., Üsekes, B. et al. Retinoid homeostasis in major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry 13, 67 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02362-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02362-0

This article is cited by

-

Altered synaptic homeostasis: a key factor in the pathophysiology of depression

Cell & Bioscience (2025)

-

Astrocytic RARγ mediates hippocampal astrocytosis and neurogenesis deficits in chronic retinoic acid-induced depression

Neuropsychopharmacology (2025)

-

Intricate mechanism of anxiety disorder, recognizing the potential role of gut microbiota and therapeutic interventions

Metabolic Brain Disease (2024)