Abstract

Reward processing dysfunctions e.g., anhedonia, apathy, are common in stress-related neuropsychiatric disorders including depression and schizophrenia, and there are currently no established therapies. One potential therapeutic approach is restoration of reward anticipation during appetitive behavior, deficits in which co-occur with attenuated nucleus accumbens (NAc) activity, possibly due to NAc inhibition of mesolimbic dopamine (DA) signaling. Targeting NAc regulation of ventral tegmental area (VTA) DA neuron responsiveness to reward cues could involve either the direct or indirect—via ventral pallidium (VP)—pathways. One candidate is the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR52, expressed by DA receptor 2 NAc neurons that project to VP. In mouse brain-slice preparations, GPR52 inverse agonist (GPR52-IA) attenuated evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents at NAc-VP neurons, which could disinhibit VTA DA neurons. A mouse model in which chronic social stress leads to reduced reward learning and effortful motivation was applied to investigate GPR52-IA behavioral effects. Control and chronically stressed mice underwent a discriminative learning test of tone-appetitive behavior-sucrose reinforcement: stress reduced appetitive responding and discriminative learning, and these anticipatory behaviors were dose-dependently reinstated by GPR52-IA. The same mice then underwent an effortful motivation test of operant behavior-tone-sucrose reinforcement: stress reduced effortful motivation and GPR52-IA dose-dependently restored it. In a new cohort, GRABDA-sensor fibre photometry was used to measure NAc DA activity during the motivation test: in stressed mice, reduced motivation co-occurred with attenuated NAc DA activity specifically to the tone that signaled reinforcement of effortful behavior, and GPR52-IA ameliorated both deficits. These findings: (1) Demonstrate preclinical efficacy of GPR52 inverse agonism for stress-related deficits in reward anticipation during appetitive behavior. (2) Suggest that GPR52-dependent disinhibition of the NAc-VP-VTA-NAc circuit, leading to increased phasic NAc DA signaling of earned incentive stimuli, could account for these clinically relevant effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deficits in reward processing and behavior are common in stress-related neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders, including major depression (MD) [1,2,3], schizophrenia [4, 5], Alzheimer’s disease [6] and Parkinson’s disease [7]. Anhedonia is a reduction in interest or pleasure in daily activities, and apathy is a reduction in motivation for physical or cognitive goal-directed behavior and in emotional reactivity; these amotivational states are inter-related and often comorbid [2, 3, 8, 9]. Both the research domain criteria (RDoC) framework’s construct of positive valence [10, 11] and the animal behavior frameworks of appetitive-consummatory reward (e.g. [12]) emphasize the fundamental importance of reward expectancy/anticipation/incentive motivation. This includes learning the association between a predictive stimulus or behavioral action and primary reward, and assessing the incentive salience of reward relative to the effort required to obtain it [3, 8, 13,14,15]. Impairments in these processes are major candidates to underlie anhedonia or apathy.

Human functional imaging studies have compared MD subjects with healthy controls in terms of stimulus-related changes in brain region-specific blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) activity during reward processing tasks; MD-related differences in basal amygdala activation are common [2, 8, 16]. Several studies have used the monetary incentive delay task, which allows for assessment of BOLD activity during exposure to the predictive stimulus (anticipation phase) and the primary reward stimulus (consummatory phase) [17]. Relative to healthy controls, MD subjects often display reduced activity in the ventral striatum, including nucleus accumbens (NAc), to the predictive stimulus but typical activity to the primary reward [18,19,20]. Such findings suggest that restoring mesolimbic pathway signaling during predictive stimulus processing (reward anticipation) could be an effective strategy for treating amotivation.

Current detailed knowledge of neural circuitry underlying reward processing comes primarily from animal studies. The ventral tegmental area (VTA) contains most of the dopamine (DA) neurons involved in reward signaling; many of these are mesolimbic DA neurons projecting to NAc GABA medium spiny neurons (MSNs). In NAc core and shell, and their respective subregions, MSN populations encode primary reward stimuli, conditioned and discriminative reward stimuli, and incentive-motivated appetitive behavior including reward approach and operant responses [12, 16, 21, 22]. The NAc MSNs express either DA receptor 1 (D1R) coupled to excitatory Gs protein, or D2R coupled to inhibitory Gi protein [22]. Many NAc D1R MSNs project back to VTA and, via GABA interneurons, stimulate DA neurons by disinhibition (direct NAc pathway of VTA regulation) [23, 24]. A similar number of NAc D1R MSNs project to ventral pallidum (VP) GABA neurons. Furthermore, the majority of NAc D1R MSNs collateralize to both VTA and VP [24]. Many NAc D2R MSNs project to ventral pallidum (VP) GABA neurons, which themselves project to VTA and either directly, or via GABA (inter)neurons, regulate DA neurons (indirect NAc pathway of VTA regulation) [25,26,27].

Etiological association between chronic stress and reward processing pathologies in MD and other disorders is well-recognized [3, 28]; etio-pathophysiological understanding and more efficacious treatments remain wanting, however. Valid animal models are essential to establish precise cause-effect relationships between chronic stress, changes in neural signaling and reward processing. In male mice, we have established a model in which chronic social stress (CSS) leads to deficits in tests of discriminative reward learning and effortful reward motivation, where each test comprises operant responding and both incentive motivation and reinforcement phases [29,30,31,32]. Furthermore, fibre photometry has been integrated into these mouse CSS-amotivation models for in vivo investigation of neural signaling during behavioral testing [31], including NAc DA activity [33].

In addition to the DA receptors, one of several further GPCRs with high striatal expression is the orphan Gs-coupled receptor GPR52. In human and rodents, GPR52 is highly expressed in striatum: around 70% of total GPR52 gene expression, primarily in NAc and also in caudate and putamen. GPR52 is also expressed in some limbic (e.g. amygdala, hippocampus) and cortical (e.g. frontal cortex) brain regions [34]. In mouse, in MSNs of NAc and dorsal striatum, Gpr52 mRNA is co-expressed with D2R mRNA [35, 36]. Gpr52 knockout mice display reduced anxiety [35]. At the protein level, GPR52 is localized at axon terminals of striatal D2R MSNs, including in VP. With respect to its endogenous ligand, it has been speculated that GPR52 could be self-activating, based on the in vitro evidence that GPR52 can induce a high level of basal activity in the absence of an agonist, measured in GPR52-transfected cells as changes in gene expression under control of the cAMP response element [37]. As an excitatory Gs-coupled receptor, axonal GPR52 could increase GABA synaptic release. Given the co-expression and opposing actions of GPR52 (excitatory) and D2R (inhibitory), it has been proposed that GPR52 agonists could counteract D2R signaling and thereby exert antipsychotic-like drug effects [34, 35, 38]. On the other hand, in a brain state of reduced mesolimbic DA function and amotivaton, NAc D2R-MSNs will become disinhibited and their inhibition, via GPR52 inverse agonism, could constitute a therapeutic strategy. In line with this latter concept, the current study investigated effects of a GPR52 inverse agonist (GPR52-IA) on: NAc-VP electrophysiology in brain slices from control mice; behavior in the mouse models of CSS-induced deficient reward learning and effortful reward motivation; using DA sensors [39], NAc DA activity coincident with effortful responding, incentive motivation and reinforcement in the CSS-reward motivation model, in which CSS leads to reduced NAc DA activity coincident with reduced incentive motivation [33]. The iterative experiments yield neural and behavioral preclinical evidence that GPR52 inverse agonism can ameliorate chronic stress-induced deficits in reward processing and behavior.

Materials and methods

Animals

An ex vivo electrophysiology experiment was conducted at Boehringer Ingelheim, Germany, with C57BL/6JRj (BL/6) male mice obtained from Janvier Labs aged 6 weeks. In vivo experiments were conducted at the University of Zurich with BL/6 male mice bred in house (breeding stock from Janvier Labs) and aged 10 weeks at experiment onset. See Supplementary Information for further details.

Ethics approval

All in vivo procedures were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The experiment conducted at Boehringer Ingelheim, Germany, was authorized by the Local Animal Care and Use Committee, and conducted in compliance with local animal care guidelines, AAALAC (Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care) regulations and the USDA Animal Welfare Act (19-025-G and 20-014-O). The experiments conducted at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, were authorized by the Veterinary Office of Canton Zurich (licenses ZH-155/2018, ZH-038/2022) and conducted in compliance with the Swiss Animal (Protection) Act.

Experimental designs

Three experiments were conducted: (1) Effect of GPR52 inverse agonist (GPR52-IA) on synaptic transmission at NAc-MSN projections to VP neurons in coronal brain slices from otherwise unmanipulated mice (n = 15). (2) Effects of stress and GPR52-IA on behavior in tests of discriminative reward learning-memory (DRLM) and reward-to-effort valuation (REV) (n = 80) using a randomized design. (3) Effects of stress and GPR52-IA on behavior and NAc DA activity in the REV test using a crossover design for GPR52-IA effects (n = 28). For experiments 2 and 3, data from previous behavioral pharmacology experiments with CSS-reward model were used for power analyses: The design was a completely randomized balanced design with 2 treatment factors with 2 groups in treatment factor A (CON, CSS) and 3 or 2 groups in treatment factor B (VEH, GPR52-IA 1 or 2 doses). The family-wise type I error was 0.05, the type II error was 0.1, and a two-sided test was used. The number of major preplanned comparisons was 3 (CSS-VEH vs CON-VEH, CON-VEH vs CON-GPR52-IA, CSS-VEH vs CSS-GPR52-IA), thus the type I error was adjusted using Bonferroni method to 0.0167. Effect size of 15 (between-group mean difference in rewards earned) with an estimated equal standard deviation of 12, were used. For detection, this yielded a required sample size of 11–12 mice in each combined (group × dose) group. This output was generated using daewr::Fpower2() embedded in SampleSizeR available at https://shiny.math.uzh.ch/git/reinhard.furrer/SampleSizeR/. It was not possible to conduct blinding with respect to CSS and CON grouping; the experimenter was blinded with respect to dose grouping.

GPR52 inverse agonist

The GPR52 inverse agonist was provided by Boehringer Ingelheim. For details of establishing in vitro potency, plasma-protein binding and selectivity, as well as in vivo pharmacokinetics, see Supplementary Information (Tables S1–S3, Figs. S1, S2).

Experiment 1: Effect of GPR52-IA on NAc MSN-VP neuron post-synaptic electrophysiology in coronal slices

Slice-preparation electrophysiology

A viral vector expressing the excitatory opsin channel rhodopsin (ssAAV8-hSyn-mChr2-mCherry, 2.92 × 1014 vg/ml, 200 nl) was injected bilaterally in NAc. At 3–4 weeks post-injection, mice (n = 7 contributing 1–2 slices to vehicle group, n = 8 contributing 1–2 slices to GPR52-IA group) were decapitated under deep isoflurane anesthesia, brains were rapidly removed, and coronal slices (250 µm) were prepared. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were performed from ventral pallidum (VP) neurons. NAc MSN terminals expressing ChR2-mCherry were visualized by epifluorescence and activated by flashing blue light (470 nm; 1 ms at 0.1 Hz). Paired photo-stimulation (50 ms inter-stimulus interval) was applied to evoke Inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) in VP neurons at a holding potential of 0 mV. Baseline responses were measured for 10–15 min, after which GPR52-IA or vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) was washed in for 40 min. Analysis was performed using Clampfit (Molecular Devices), Igor pro 8 (Wavemetrics), and Prism (version 9.5, GraphPad Software Inc.). For details, see Supplementary Information.

Experiment 2: Effects of CSS and GPR52-IA on behavior in the DRLM and REV tests

Behavioral conditioning

Prior to conditioning (training), body weight (BW) per mouse and food intake per littermate pair were measured for each 24 h across 1 week (Table S4). Beginning the following week, mice were food restricted so that BW was reduced to 90–95% of baseline (BBW) to ensure adequate motivation for conditioning using sucrose pellet reinforcement. For details see Supplementary Information.

Chronic social stress (CSS)

The chronic social stress (CSS) procedure used is based on the resident-intruder paradigm [40, 41]. Pairs of littermates were assigned to control (CON) or CSS groups. Resident mice were singly-caged aggressive, ex-breeder CD-1 males (40–55 g), and a transparent, perforated divider was placed along the length of each home cage. On each of 15 days, a CSS mouse was placed in the same compartment as an unfamiliar CD-1 mouse for a cumulative total of 30–60 s physical attack or 10 min maximum, whichever occurred sooner. Thereafter, the two mice were placed either side of the divider, and remained in distal (visual, olfactory, auditory) contact for 24 h. For model validity it is essential that the environmental stressor of CSS is not confounded by bite wounding: in addition to restricting daily attacks to 60 s, the lower incisor teeth of CD-1 mice were checked/trimmed every third day [40, 41]. CON mice were kept in littermate pairs and handled for weighing on each of the 15 days. At days 5–12 of the CSS/CON protocol, BW and food intake were measured daily; mean values of BW and daily food intake were used as re-baseline values for these parameters (re-BBW, re-B-food intake) and applied during behavioral testing (Table S4).

Behavioral pharmacology testing

Starting on day 13 of CSS/CON and continuing until the last day of testing, mice were mildly food restricted to yield 95–100% re-BBW directly prior to each test session (see Supplementary Information, Table S4). Testing began 2 days after CSS/CON, and was carried out on 6 consecutive days, with 3 daily DRLM tests followed by 3 daily REV tests. On each of these days, 60 min prior to testing, mice received one of vehicle, GPR52-IA at 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg p.o.

Discriminative reward learning-memory (DRLM) test:

In operant chambers containing a feeder and no operant port, a novel tone discriminative stimulus (DS, 6.5 kHz, 80 dB) was presented for 30 s maximum and during this time 1 response into the feeder port triggered chocolate pellet delivery (within 0.3–0.5 s) and tone termination after 1 s. Per test, a total of 40 DS-reward trials were presented with variable inter-trial intervals (ITIs) of 50 ± 30 s; ITI feeder responses were counted but were without consequence. Mice were tested on 3 consecutive days. In each test, trials 1-30 were analyzed and the measures of interest were: number of rewards obtained (= number of trials with a DS response); median DS response latency (trials without a response were given latency = 30 s); median ITI response interval (ITI duration/feeder responses per ITI); discriminative learning ratio (= median ITI response interval/median DS response latency) [30, 31].

Reward-to-effort valuation (REV) test:

Beginning on the day after DRLM testing, an operant nose-poke port was placed in the chamber. The session duration was 45 min, and no break point was used. Each session was initiated with operant port LED illumination, and 1 operant response triggered switching off the LED, a tone DS for 1 s (6.5 kHz, 80 dB) and chocolate pellet delivery into the feeder; feeder-port response/pellet retrieval was followed by a 5 s time out. A progressive ratio (PR) schedule was used as follows: trials 1–5 at PR 1, trials 6–10 at PR 5, trials 11–15 at PR 9, trials 16–20 at PR 13, and so on. Mice were tested on 3 consecutive days: REV test 1 test served as a transition test from DRLM test conditions, and the data from REV tests 2 and 3 were used for analysis. For REV test 3, a pellet of normal diet provided a low-effort/low-reward alternative to chocolate pellets (choice test). The main measures of interest were total number of operant responses, number of chocolate pellets earned, and final ratio attained [30, 31]. For further details see Supplementary Information.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism (GraphPad, version 9) or SPSS (IBM, version 29). Data sets were first assessed for outliers, using the ROUT test or Boxplot analysis; no outliers were present. Data were checked for normal distribution, using the D’Agostino-Pearson normality test and the Shapiro-Wilk test. Homogeneity of variance was confirmed using Levene’s test. For each dependent variable, a linear mixed model was run with fixed effects of group (G) and dose (D), and of test day (T) in the case of DRLM testing, and a random effect of mouse subject. Significant (p < 0.05) main or interaction effects were analyzed using Sidak’s post hoc multiple comparisons test. Graphs were prepared using Prism (GraphPad, version 9), with data presented as means and standard error of the mean being used as an estimate of variation.

Experiment 3: Effects of CSS and GPR52-IA on behavior and NAc DA release in the REV test

Behavioral conditioning

Behavioral conditioning was conducted as described for Experiment 2 with modifications to prepare the mice for combined behavioral testing and fibre photometry (see Supplementary Information).

Stereotactic surgery and adeno-associated viral vectors

Stereotactic surgery was conducted according to a published protocol [31, 42]. To quantify release of DA in the NAc (referred to as NAc DA activity), a GRABDA sensor adeno-associated viral vector (pAAVss_hsyn-GRAB-DA4.4, 1.1 × 1013 vg/ml, 350 nl; Boehringer Ingelheim) [33, 39] was injected unilaterally in the NAc (core, primarily, and shell). As a control to determine whether certain behaviors (e.g. operant responding, pellet retrieval) generated movement-related artifacts in the fibre photometry signal, additional mice were injected in NAc with an EGFP viral vector (ssAAV-9/2-hSyn1-EGFP-WPRE-hGHp(A, 2.9 × 1013 vg/ml, 350 nl; Viral Vector Facility, ETH and University of Zurich) [43]. A fibre-optic probe (Ø = 200 µm) was implanted directly dorsally to the NAc injection site. After recovery, mice were given two additional behavioral conditioning sessions with the fibre photometry patch cord attached, to allow adjustment to the conditions to be used at testing. For further details see Supplementary Information.

Chronic social stress

CSS was conducted as described for Experiment 2 with the following modification: during the attack periods, the central cage divider was removed to avoid collision with the optic fibre and therefore the potential for mouse injury or optic fibre damage.

Fibre photometry

Fibre photometry for optical recording of brain activity in freely-moving mice during behavioral testing was conducted as described previously [31, 33, 43, 44] and in Supplementary Information.

Testing effects of CSS and GPR52-IA on behavior and NAc DA activity

On the day after CSS/CON completion, mice were placed in the photometry conditioning/test chamber without any stimuli and connected to a patch cord: the GRABDA photometry signal of each mouse was recorded for 15 min to check for a sufficient and stable signal. Mice were then given 3 REV tests on 4 consecutive days and a counterbalanced cross-over design was used to investigate the effects of GPR52-IA at 10 mg/kg versus VEH administered at 60 min pre-testing: day 1: REV test 1 only; day 2: GPR52-IA/VEH + REV test 2 (CON mice 1–7, CSS mice 1–7: VEH; CON mice 8–14, CSS mice 8–14: GPR52-IA); day 3: wash out; day 4: GPR52-IA/VEH + REV test 3 (CON mice 1–7, CSS mice 1–7: GPR52-IA; CON mice 8–14, CSS mice 8–14: VEH). There were some changes in REV test parameters compared to Experiment 2: session duration was 30 min and a shallower PR schedule was used (trials 1–5 at PR 1, trials 6–10 at PR 3, trials 11–15 at PR 5, trials 16–20 at PR 7, and so on); none of the REV tests included a pellet of normal food. Details of analysis of NAc DA activity (and EGFP signal) data are given in Supplementary Information.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of each behavioral variable was conducted using 2-way ANOVA with a between-subject factor of group (G) and a within-subject factor of dose (D). Significant interaction effects were analyzed using Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. For NAc DA activity during specific REV test phases, statistical analysis was conducted using linear mixed models with fixed effects of group (G), dose (D) and time-normalized interval (I) or time in seconds (S), and a random effect of mouse subject. Significant main or interaction effects were analyzed using Sidak’s test.

Results

GPR52 inverse agonist

The in vitro on-target potency (EC50) of the GPR52 inverse agonist (GPR52-IA), as determined using CHO cells over-expressing murine GPR52 and measuring dose-dependent lowering of cAMP levels, was 8 nM (Fig. S1, Table S1). To assess suitability of GPR52-IA for in vivo experiments, in vitro and mouse in vivo pharmacokinetic properties were studied (Fig. S2, Tables S1 and S2). GPR52-IA showed high binding to mouse plasma proteins (fraction unbound, fu < 0.00179). Brain penetration was good, with an in vivo efflux of 0.54 (muscle/brain ratio at 1 h after p.o. dosing with 20 mg/kg). It is also important to note that 24 h after compound administration, the plasma concentration was only about 1% of peak concentration (Fig. S2), making any accumulation over days unlikely in the case of repeated daily dosing. The pharmacokinetic parameters supported investigation of GPR52-IA in mouse neuropsychopharmacology experiments: 3 and 10 mg/kg were applied in Experiment 2, and 10 mg/kg in Experiment 3. Plasma concentration (Cplasma) at 1–2 h after intragastric gavage was estimated via extrapolation to be ≈700 nM (3 mg/kg) and ≈2500 nM (10 mg/kg), suggesting brain unbound (free) concentrations of ≈2 nM and ≈8 nM, respectively (see Supplementary Information, In vivo pharmacokinetic and distribution studies in mice). Thus, in experiments, the estimated free brain concentration of GPR52-IA was ≈0.3× (3 mg/kg) and ≈1.0× (10 mg/kg) in vitro EC50 (Table S2). Concerning off-target activity, using the Eurofins SafetyScreen44™ panel of CNS targets and GPR52-IA at 10 µM, relative to other off-targets investigated, activity was highest at serotonin receptor 5-HT2A (Table S3). However, given that potency at GPR52 was 8 nM, activity at 5-HT2A would be expected to be negligible in comparison (estimated EC50 ≈ 300 nM, see Supplementary Information, Off-target activity).

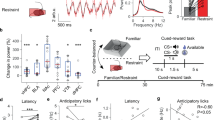

Experiment 1: GPR52 inverse agonism decreases inhibitory transmission at NAc MSN-VP neuron synapses

To investigate for ex vivo evidence of involvement of the NAc-VP-VTA indirect pathway in mediating any effects of GPR52-IA observed in vivo, GPR52-IA effects on transmission at NAc MSN-VP neuron synapses were studied in slice preparation. Unmanipulated (control) male BL/6 mice underwent stereotactic surgery for bilateral injection in NAc (core, primarily, and shell) of AAV vector expressing channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2), which projected anterogradely to VP (Fig S3). In coronal slices, using whole-cell voltage clamp recording from dorsal VP neurons, paired optical stimulation of NAc MSN terminals evoked GABAergic inhibitory postsynaptic currents (eIPSCs) (Fig. 1A–C). The onset of the eIPSC response after optical stimulation had a latency of 5–7 ms, and was therefore short and consistent with mono-synaptic NAc MSN-VP neuron transmission. Furthermore, the variance in this response latency (i.e., the response jitter) was minimal and therefore also consistent with monosynaptic connectivity (Fig. 1C). After recording baseline responses, GPR52-IA (1 mM) or vehicle (DMSO 0.1%) was washed in, and their effect on inhibitory transmission was measured as the relative change in peak response amplitude. Relative to vehicle, GPR52-IA reduced the amplitude of eIPSCs in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1C, D): eIPSC amplitude was 78.7% ± 5.5% of baseline over the course of the 30–40 min application compared with 99.5% ± 3.9% during vehicle application (dose main effect: F1, 20 = 10.57, p = 0.004; dose × time interaction effect: F8, 155 = 4.62, p < 0.0001; Fig. 1D). The area under the curve (AUC) during the time course 0–40 min was smaller following GPR52-IA than vehicle (Student’s independent t test, t20 = 3.205, p = 0.004; Fig. 1E). These results suggest a modulatory—specifically, inhibitory—effect of GPR52-IA on GABA release at NAc MSN to VP neuron synapses. This could result in disinhibition of VP GABA neurons projecting to GABA (inter)neurons in the VTA (see “Discussion”).

A Schematic of the experimental design. AAV vector for ChR2 was injected into the NAc. Terminals of the infected MSNs (red) were activated with 470 nm light and responses were recorded in VP neurons. B Overlapped differential interference contrast and fluorescence image of a coronal slice (bregma 0.40 mm) in the recording chamber, with the recording electrode (shown by the arrow) placed at mCherry+ terminals in the VP. C Representative traces of IPSCs in VP neurons that were evoked by paired photo stimulation (blue bars, 50 ms inter-stimulus interval) of MSN terminals before (baseline) and after bath application of vehicle (individual traces in blue and average in black) or GPR52-IA (individual traces in red and average in black). Calibration bars represent 50 ms, 50 PA. D Time course of IPSC amplitude evoked by the photo stimulation of MSN terminals before and after bath application of GPR52-IA (red) or VEH (blue). Statistical analysis was conducted using linear mixed model with fixed effects of dose (D) and time (T) and a random effect of mouse subject. Significant interaction effects were analyzed using Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.05. E The area under the curve (AUC) of the time-course (0–40 min) of eIPSCs in VP neurons in GPR52-IA- and VEH-treated slices. **p = 0.004. Data shown are mean ± s.e.m. NAC nucleus accumbens, VP ventral pallidum, ac anterior commissure, Str striatum.

Experiment 2: Chronic social stress deficits in reward learning and motivation ameliorated by GPR52 inverse agonism

Male BL/6 mice that had undergone conditioning for behavioral tests (Fig. 2A) underwent either control handling (CON) or chronic social stress (CSS) (Fig. 2B). The mean duration of attack experienced by CSS mice was 43.5 ± 4.2 s per day; all CSS mice were submissive during proximal exposure. During CSS/CON, daily food consumption was measured and during behavioral testing mice were given sufficient food to maintain body weight at 95–100% baseline, so that sweet-tasting food provided reinforcement as gustatory reward and not hunger satiety (Table S4). Beginning 2 days after CSS/CON, mice underwent 6 days of behavioral testing with chocolate pellet reinforcement. At 1 h prior to each test session, compound was administered via intragastric gavage, with mice allocated to receive vehicle (VEH/0), 3 or 10 mg/kg GPR52-IA at 10 mL/kg body weight.

A Experimental design. BBW + FC: measurement of baseline body weight and food consumption; 90–95% BBW/Conditioning: conditioning under food restriction that reduced BW to 90–95% BBW; CSS/CON: CSS protocol or control handling; Ad lib food re-BBW + FC: BW and food consumption under ad libitum feeding on days 5–12 of CSS/CON provided re-baseline values; 95–100% re-BBW: mice were mildly food restricted to be tested at 95–100% re-BBW. B CSS and CON protocols. C–G Discriminative reward learning-memory (DRLM) test. C Tone discriminative stimulus (DS) signaled chocolate pellet availability following a feeder response; maximum DS duration was 30 s per trial and inter-trial intervals (ITIs) were 20–80 s (mean = 50 s). Mice received 3 daily tests of 40 trials each and trials 1–30 per test were used for data analysis. Data are shown as mean ± SEM per test and individual mouse scores. Statistical analysis was conducted using linear mixed models with fixed effects of group (G), dose (D) and test (T) and a random effect of mouse subject. Significant main or interaction effects were analyzed using Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Test days indicated by different letters were significantly different (p < 0.05). D Number of chocolate pellets obtained i.e. DS trials with a response. E Median DS response latency. F Median ITI response interval. G Median learning ratio (ITI response interval/DS response latency. H–K Reward-to-effort valuation (REV) test 2. H Nose-poke responses at an operant stimulus triggered 1 s tone DS and delivery of chocolate sucrose pellets on a progressive ratio (PR) schedule (5 trials at PR1, 5 × PR5, 5 × PR9, 5 × PR13, etc.). Statistical analysis was conducted using linear mixed models with fixed effects of group (G) and dose (D) and a random effect of mouse subject. I Number of operant responses. J Number of chocolate pellets earned. K Final ratio attained. L–P REV test 3 with freely-available normal food pellet. L A pellet of normal food provided a low-reward/low-effort choice to operant responding for chocolate pellets. M Number of operant responses. N Number of chocolate pellets earned. O Final ratio attained. P Weight of normal pellet eaten.

Mice were given a discriminative reward learning-memory (DRLM) test on 3 consecutive days (Fig. 2C). An initially neutral tone of maximum 30 s per trial (discriminative stimulus, DS) indicated the period within which a feeder response triggered DS termination and delivery of a chocolate pellet into the feeder. Relative to CON-VEH mice, CSS-VEH mice: made fewer DS feeder responses and therefore obtained fewer rewards (Fig. 2D); had longer DS response latencies (Fig. 2E); had longer ITI response intervals (mean interval between successive responses per ITI) that decreased across tests, whereas in CON mice they increased across tests (Fig. 2F). A discriminative learning ratio was calculated as ITI response interval/DS response latency, and this was lower in CSS-VEH than CON-VEH mice (Fig. 2G). It is important to note that CSS-VEH mice completed fewer reinforced trials (38.9 ± 12.5, mean ± SD) than CON-VEH mice (74.8 ± 12.1), and that this would contribute to their attenuated learning ratio. Whilst there was no effect of GPR52-IA on any DRLM measure in CON mice, in CSS mice that received 10 mg/kg (CSS-10) the following effects were observed relative to CSS-VEH and CSS-3 mice: increased DS feeder responses and rewards obtained (group x dose interaction effect: F2, 71 = 6.50, p < 0.003; Fig. 2D); shorter DS response latency (group × dose interaction effect: F2, 71 = 6.04, p < 0.004; Fig. 2E); shorter ITI response interval (group × dose interaction effect: F2, 71 = 3.30, p < 0.05; Fig. 2F). There was also a tendency to a higher learning ratio in CSS-10 mice (group x dose interaction effect: F2, 71 = 2.94, p = 0.06; Fig. 2G). Consequently, the DRLM behavior of CSS-10 mice was similar to that of CON mice.

The next day an operant port was introduced into the test chamber and mice underwent a reward-to-effort valuation (REV) test on 3 consecutive days (Fig. 2H). The number of chocolate-flavored sucrose pellets obtained was directly dependent on the number of operant responses, with a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement being used i.e., the number of responses required per reward increased progressively. At each trial, reaching the required ratio resulted in a 1-s tone DS and chocolate pellet delivery. REV test 1 was used to allow mice to adjust to the new test conditions following DRLM testing. At REV test 2, relative to CON-VEH mice, CSS-VEH mice made fewer operant responses (Fig. 2I), earned fewer rewards (Fig. 2J), and attained a lower final ratio (Fig. 2K). In CSS and CON mice, compared with VEH, GPR52-IA at 10 mg/kg led to more operant responses (dose main effect: F2, 71 = 3.10, p = 0.05; Fig. 2I) and more rewards earned (dose main effect: F2, 71 = 4.78, p < 0.02; Fig. 2J). In CSS mice specifically, GPR52-IA increased final ratio attained (group x dose interaction effect: F2, 71 = 3.03, p = 0.05; Fig. 2K). At REV test 3, normal food was provided as a low-reward/low-effort choice to enable identification of any hunger differences between CSS and CON mice (Fig. 2L): the amount of normal food eaten was low (mean < 0.2 g) in all groups, and similar in CSS and CON mice and across doses, indicating that mice were close to satiety for standard food (Fig. 2P). Similar to REV test 2, at REV test 3, CSS-VEH mice were less motivated to expend effort for sweet reward than were CON-VEH mice, and GPR52-IA at 10 mg/kg led to an overall increase in operant responses (dose main effect: F2, 71 = 3.92, p < 0.03; Fig. 2M), rewards earned (dose main effect: F2, 71 = 5.21, p < 0.008; Fig. 2N) and final ratio attained (dose main effect: F2, 71 = 3.91, p < 0.03; Fig. 2O).

Experiment 3: Chronic social stress deficits in reward motivation and nucleus accumbens dopamine release ameliorated by GPR52 inverse agonism

Based on the evidence that GPR52-IA at 10 mg/kg increased effortful reward motivation in CSS mice, and the hypothesis that this psychopharmacological effect is mediated by increasing reward-related NAc DA activity, in Experiment 3 a viral vector expressing a GRABDA sensor was injected in NAc and fibre photometry was used to detect GRABDA fluorescence, emitted when the sensor molecule binds DA. Behavioral conditioning was conducted as described for Experiment 2. Mice then underwent unilateral stereotactic surgery for NAc injection of GRABDA and placement of an optic fibre (Fig. 3A, I, Fig. S4). Following recovery, mice underwent CON or CSS (Fig. 3B); the mean duration of daily attack experienced by CSS mice was 50.0 ± 5.4 s, and all CSS mice were submissive to CD-1 mice during proximal exposure. During CSS/CON, daily food consumption was measured and during behavioral testing mice were fed to maintain body weight at close to baseline (Table S4). Mice were given 3 REV tests (Fig. 3C) across 4 days and the effects of GPR52-IA at 10 mg/kg were investigated using a counterbalanced cross-over design. Dosing was conducted at 1 h prior to testing using intragastric gavage. Regarding NAc DA activity, for each trial separately, the GRABDA fibre photometry signal during 10 s prior to onset of operant responding provided baseline activity: signal mean (F0) and standard deviation (SD0) were used to z-score event-related DA activity at each 0.05 s time point (t) i.e. (F(t)-F0)/SD0). Each trial was made up of 3 REV-test phases: operant phase, comprising 10 time-normalized intervals across the period from 1st to nth nose poke; discriminative stimulus (DS) phase, 10 time-normalized intervals from onset of DS to feeder response; feeder phase, from feeder response/reward retrieval until 5 s later, divided into 0.5-s intervals.

A Experimental design. Surgery + R + AAVV: stereotactic surgery, recovery, expression of AAV vector; C + OF: conditioning sessions with patch cord attached to optic fibre; SIG: fibre photometry signal test; REV: reward-to-effort valuation test; VEH + REV/CPD + REV: each mouse given 1 REV test with VEH and 1 REV test with GPR52-IA using a counterbalanced cross-over design. For other abbreviations, see Fig. 1. B CSS procedure. C Reward-to-effort valuation (REV) test with fibre photometry. Behavior: Statistical analysis was conducted using 2-way ANOVA with a between-subject factor of group (G) and a within-subject factor of GPR52-IA dose (D). Significant interaction effects were analyzed using Sidak’s test. D Number of operant responses. E Number of gustatory rewards earned. F Final ratio attained. G Operant phase duration i.e., time from 1st until 5th operant response. H Discriminative stimulus (DS) phase duration i.e., time from DS onset until feeder response. NAc DA activity: Statistical analysis was conducted using linear mixed models with fixed effects of group (G), dose (D) and interval or time (T, S) and a random effect of mouse subject. Significant main or interaction effects were analyzed using Sidak’s test. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. I Schematic showing unilateral injection site of AAV GRAB-DA Sensor in NAc, and fibre optic probe implantation directly dorsal to the injection site. J PR 5 operant phase z-scored DA activity following time-normalization using 10 equal intervals. For each mouse, the mean score for PR 5 trials was calculated and data are given as mean ± s.e.m. per group. K PR 5 DS phase z-scored DA activity following time-normalizaion using 10 equal intervals. For each mouse, the mean z-score for PR 5 trials was calculated and data are given as mean ± s.e.m. per group, as well as the overall mean and individual scores per group. L PR 5 feeder phase z-scored DA activity divided into 10 intervals of 0.5 s. For each mouse, the mean score for PR 5 trials was calculated and data are given as mean ± s.e.m per group, as well as the overall mean and individual scores per group. M DS-phase inter-individual relationship between absolute change (GPR52-IA test – VEH test) in NAc DA activity scores and rewards earned in CON mice. N DS-phase inter-individual relationship between absolute change (GPR52-IA test – VEH test) in NAc DA activity scores and rewards earned in CSS mice.

At REV test 1 without compound, CSS mice demonstrated the expected decrease in reward motivation (Fig. S5): relative to CON mice, they made fewer operant responses (Fig. S5B), earned fewer rewards (Fig. S5C) and attained a lower final ratio (Fig. S5D). For analysis of NAc DA activity, trials at progressive ratio 3 (PR 3) were used, because this was the highest ratio at which all CON and CSS mice completed trials (Fig. S5D). The duration of the operant phase was longer in CSS than CON mice (Fig. S5E); operant phase NAc DA activity was lower in CSS than CON mice in interval 1 specifically and across the remaining intervals DA activity was close to baseline in CON and CSS mice (Fig. S5G). The duration of the DS phase, i.e. time from nose-poke 3/DS-onset until feeder response, was similar in CSS and CON mice (Fig. S5F): there was a peak in NAc DA activity at intervals 2 and 3 and then a gradual decline, and there was a tendency for the peak to be lower in CSS than in CON mice (Fig. S5H). During the feeder phase, there was a peak in DA release at 0.5–1.5 s followed by a decline, and DA release was similar in CSS and CON mice (Fig. S5I).

At REV tests 2/3 with GPR52-IA/VEH administered in a counter-balanced manner (Fig. 3), compared with CON mice, CSS mice demonstrated decreased reward motivation after VEH and this deficit was ameliorated by GPR52-IA. This was the case for: number of operant responses (group × dose interaction effect: F1, 26 = 11.23, p < 0.003; Fig. 3D), number of rewards earned (group × dose interaction effect: F1, 26 = 19.84, p < 0.0001; Fig. 3E) and final ratio attained (group × dose interaction effect: F1, 26 = 16.56, p < 0.0004; Fig. 3F). For analysis of NAc DA activity, trials at PR 5 were used, because this was the highest PR which all CON and CSS mice reached in one or both of REV tests 2/3 (Fig. 3F). The duration of the operant phase was longer in CSS than CON mice and this effect was reduced by GPR52-IA (group × dose interaction effect: F1, 26 = 7.64, p = 0.01; Fig. 3G). Operant phase NAc DA activity was higher during interval 1 and during subsequent intervals was close to baseline (interval main effect: F9, 474 = 7.09, p < 0.0001); there was no effect of CSS or GPR52-IA on DA release during operant responding (Fig. 3J). The duration of the DS phase was similar in CSS and CON mice and was not significantly affected by GPR52-IA (Fig. 3H). During this phase (Fig. 3K), there was a peak in NAc DA activity at interval 2 (interval main effect: F9, 474 = 5.03, p < 0.001). Nucleus accumbens DA activity was lower in CSS than in CON mice (group main effect: F1, 26 = 8.49, p = 0.007). NAc DA activity was higher during the GPR52-IA test than the VEH test (dose main effect: F1, 480 = 59.14, p < 0.001). In a posteriori paired t-tests, whilst GPR52-IA was without significant effect in CON mice (t13 = 1.69, p = 0.11), it increased NAc DA activity consistently in CSS mice (t12 = 5.62, p < 0.0002; Fig. 3K). There was a moderate inter-individual positive association between the absolute changes (GPR52-IA – VEH) in test values for NAc DA activity and rewards earned in CSS mice (Fig. 3N), whereas there was no association in CON mice (Fig. 3M). During the feeder phase (Fig. 3L), there was a peak in NAc DA activity at 0–2 s followed by a gradual decline (interval main effect: F9, 474 = 12.09, p < 0.0001), and DA activity was similar in CSS and CON mice and similar after GPR52-IA and VEH.

To provide a negative control for whether GRABDA changes were indeed indicative of NAc DA activity and not artefacts caused by, for example, head movements, mice expressing EGFP in the NAc, the signal from which should be constant, were also investigated (Fig. S4C, D). In terms of REV-test behavior, NAc-EGFP mice resembled GRABDA CON mice (Fig. S6A–C); the EGFP signal remained at baseline across each test phase (Fig. S6D–F), suggesting the absence of artefact effects on the NAc DA activity signal measured in the GRABDA experimental mice.

Discussion

Dysfunctional reward processing is common in various brain disorders and precision therapies are currently lacking. Understanding such clinical states is complex at the levels of: specific behavioral processes that contribute to reward psychopathology; neural circuitries underlying these behavioral processes; etio-pathophysiology in neural circuitries. Here, we integrated mouse experiments that address these different levels to investigate the potential involvement of the orphan receptor GPR52 in the neurobehavioral regulation of reward processing and amelioration of stress-induced deficits therein. The study was made possible by the availability of a potent and selective inverse agonist of GPR52, which was applied in iterative in vitro and in vivo experiments in mice in basal and stress-related states.

The in vitro experiment was informed by the neuroanatomical evidence that Gpr52 mRNA is co-expressed with D2R mRNA in NAc [35, 36], substantial proportion of NAc D2R-MSNs project to the VP and thereby contribute to the indirect NAc pathway of VTA DA neuron regulation, and substantial GPR52 protein is located in the NAc MSN axonal terminals in the VP [35]. We were therefore interested in investigating whether the GPR52-IA would act at the excitatory Gs-coupled receptor to inhibit signaling at synapses of NAc MSNs with VP neurons. Indeed, during optogenetic stimulation of the NAc MSN-VP neuron pathway, GPR52-IA attenuated the amplitude of evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents. The VP neurons which project to the VTA are also GABA-ergic; some of those that project to the VTA form synapses with GABA (inter)neurons that project to DA neurons [25,26,27]. Concerning this circuit, GPR52-IA inhibition of GABA release at NAc D2R-MSN terminals synapsing with VP GABA neurons would disinhibit the latter, and increase VP inhibition of VTA GABA (inter)neurons, thereby disinhibiting VTA DA neurons. Given this in vitro finding, we proceeded to investigate the effects of GPR52-IA on reward-directed learning and motivation, and in particular in mice that had undergone chronic social stress and would therefore be expected to be deficient in reward-directed behavior [29,30,31,32].

Indeed, compared with CON-VEH mice, CSS-VEH mice responded less in the DRLM test and therefore obtained fewer rewards. This reduced experiencing of the reinforcement contingency would likely contribute to attenuated learning by CSS mice, in addition to any direct impairment of tone-behavior-sucrose association learning. With GPR52-IA at 10 mg/kg, responding increased in CSS mice, and the value of the learning ratio approached that in CON mice, in which GPR52-IA was without effect. The amelioration of the CSS effect by GPR52-IA could be due to one or more of: increased learning of the tone-behaviour-sucrose contingency and enhanced reward anticipation, reduced sensitivity to non-reinforcement at feeder responses during inter-trial intervals, increased affective responding to sucrose. In the REV test, in the same CSS mice, GPR52-IA at 10 mg/kg led to increased effortful motivation on the contingency, repeated operant responding-tone-sucrose reinforcement, and there was also a mild pro-motivational effect in CON mice at this dose. Again, it is possible that GPR52-IA led to one or more of reduced sensitivity to progressively increasing effort, increased learning of the tone-sucrose contingency and enhanced reward anticipation, reinstatement of sucrose affective response. Interestingly, in the case of GPR139, another orphan GPCR that is highly expressed in NAc [45, 46], an agonist was without any effect on responding or learning by CSS mice in the DRLM test, whereas it did increase their effortful motivation in the REV test [32]. This demonstrates that the two tests are indeed recruiting different behavioral processes that are underlain by different neural circuitries. It is noteworthy that the marked pro-motivational effect of GPR52-IA was still present at REV test 3 and therefore following 6 days of compound administration, consistent with the absence of tachyphylaxis at GPR52.

To increase understanding of the behavioral processes and pathways via which GPR52 inverse agonism is efficacious in reinstating typical levels of (discriminative) reward responding in CSS mice, we conducted a follow-on experiment that incorporated fibre photometry with GRABDA sensors to measure NAc DA activity in CON and CSS mice during each phase of the REV test. In a previous study, it was shown that CSS leads to an attenuated increase in NAc DA activity in response to the tone DS that announces reward whereas the increase in NAc DA activity in response to reward per se is similar to that in CON mice, i.e., reduced reward motivation co-occurs with reduced NAc DA activity at reward anticipation [33]. Again, there was a deficit in effortful motivation in the CSS mice and again this deficit was ameliorated by GPR52-IA at 10 mg/kg. The effect size of GPR52-IA was somewhat reduced compared with the previous experiment, suggesting that repeating dosing increases the efficacy of GPR52-IA. In CSS-VEH compared with CON mice, the operant phase was longer, reflective of a lower rate of operant responding, and was shortened in CSS mice after GPR52-IA to a CON-like duration. In all group-dose conditions, mice displayed a small increase in NAc DA activity at the first operant response of a trial, after which activity remained close to baseline across the operant phase. Reaching the required number of operant responses was indicated by a 1-sec tone DS, and, whereas CON-VEH mice responded to this with a clear peak in NAc DA activity, this was not the case in CSS mice after VEH. GPR52-IA increased DS-related NAc DA activity in CSS and CON mice, and the net effect was that CSS mice after GPR52-IA had similar NAc DA activity to CON mice after VEH in this reward anticipation phase, and they completed more REV trials and with faster operant responding. There was also a moderate association between the extent of increases in NAc DA activity and rewards earned after GPR52-IA, providing further, indirect evidence for a causal NAc DA-reward motivation relationship. As noted above, it is possible that CSS increased sensitivity to progressively increasing effort or decreased learning of the tone-sucrose contingency and thereby reward anticipation. By reinstating a typical level of NAc DA activity in response to the DS, GPR52 inverse agonism ameliorated the effects of the neural changes underlying one or both of these CSS-related behavioral states. The effects of CSS and GPR52-IA on NAc DA activity were specific to the DS phase of reward anticipation, with mice in all group-dose conditions displaying a similar marked peak in NAc DA activity at sucrose reward retrieval and consummation. These findings represent a back-translation of the clinical findings of attenuated fMRI BOLD activity in the ventral striatum specific to the anticipation phase of the monetary incentive delay task in human subjects with MD compared with healthy controls [18,19,20].

Integrating the current findings for GPR52-IA in terms of in vitro evidence for inhibition of NAc D2R-MSN—VP GABA neuron evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents, and in vivo evidence from CSS mice for reinstatement of adaptive levels of effortful motivation for reward underlain by increased NAc DA activity in response to an incentive stimulus that signals end of responding/reward delivery, we would propose the following circuit as a possible explanation (Fig. 4): Previous rodent studies have reported that chronic stress leads to fewer VTA DA neurons displaying burst firing [47] or to shorter bursts and fewer spikes per burst by these neurons [48]. These changes might lead to less NAc DA activity [49, 50]. Reduced binding of DA at D2R-MSNs would lead to disinhibition of these neurons [51], including those projecting to VP [22]. Increased firing at NAc D2R-MSN—VP GABA neuron synapses would increase inhibitory postsynaptic currents. In turn, this would decrease firing at VP GABA neuron—VTA neuron synapses, which would include GABA interneurons [25] and rostro-medial tegmentum (RMTg) GABA neurons [26, 27]. The disinhibition of these VTA GABA neuron populations would increase inhibition of VTA DA neurons. Within this indirect-pathway circuit of attenuated firing of VTA DA neurons and NAc DA activity, inverse agonism of GPR52 at the axon terminals of NAc D2R-MSNs synapsing with VP GABA neurons would disinhibit the latter and thereby disinhibit the VTA DA neurons projecting to NAc. According to the current findings, NAc D2R-MSN-VP GABA neuron disinhibition would result in increased NAc DA activity in response to an effort-related discriminative stimulus. This requires integration of the proposed circuit with an additional pathway(s) for the processing of “effortful responding leads to incentive stimulus”: One candidate would be the aversion-responsive basal amygdala (BA) glutamate neurons that project to NAc D2-MSNs [52]. Interestingly, CSS leads to an increase in the Ca2+-activity of BA-NAc neurons during the operant and DS phases of the REV test [31]. Simultaneous high BA-NAc D2R-MSN glutamate excitation and low VTA-NAc D2R-MSN DA inhibition would lead to high activity in the NAc D2R-MSN—VP GABA neuron pathway, and therefore to a sensitive node for GPR52 inverse agonism (Fig. 4). Clearly, follow up experiments will be needed to investigate questions emerging from the current data and their interpretation. One of these would be to determine whether intra-VP administration of GPR52-IA recapitulates the effects of systemic GPR52-IA on reward-related behavior and NAc DA activity. Another would be to determine whether the attenuation of IPSCs in VP GABA neurons post-synaptic to NAc D2R-MSNs by GPR52-IA leads to increased firing of these neurons. It is also important to note that there are some VP glutamate neurons that project to VTA [53], but it is currently unclear as to whether these are post-synaptic to NAc D2R-MSNs.

The current findings are interpreted within the framework of the indirect NAc pathway of VTA regulation. It should be noted that the depiction that VP GABA neurons that are post-synaptic to NAc D2R MSNs themselves project to VTA or RMTg is an assumption, albeit widely accepted as an integral component of the indirect pathway. A Basal state: an adaptive level of firing by VTA DA neurons results in adaptive DA release on to NAc MSNs. NAc D2R-MSNs binding of DA reduces their firing and inhibition of VP GABA neurons. VP GABA neurons exert adaptive inhibition of VTA GABA interneurons and RMTg GABA neurons. VTA/RMTg GABA (inter)neurons exert adaptive inhibition on VTA DA neurons. Appetitive behavior leading to an incentive stimulus is processed as primarily rewarding by BA glutamate aversion neurons (A) and reward neurons (R) projecting to NAc D2R- and D1R-MSNs, respectively: phasic DA release is adaptive and incentive motivation is high. B Chronic stress state: a low level of firing by VTA DA neurons results in low DA release on to NAc MSNs. NAc D2R-MSNs binding low DA increases their firing and inhibition of VP GABA neurons. VP GABA neurons exert low inhibition of VTA GABA interneurons and RMTg GABA neurons. VTA/RMTg GABA (inter)neurons exert high inhibition of VTA DA neurons. Appetitive behavior leading to an incentive stimulus is processed as primarily aversive by BA A and R projecting to NAc D2R- and D1R-MSNs, respectively: phasic DA release is low and incentive motivation is low. C Chronic stress state and GPR52 inverse agonist: a low level of firing by VTA DA neurons results in reduced DA release. NAc D2R-MSNs binding low DA increase their firing but inhibition of VP GABA neurons is blocked by GPR52 inverse agonist. VP GABA neurons exert adaptive inhibition of VTA GABA interneurons and RMTg GABA neurons. VTA/RMTg GABA (inter)neurons exert low inhibition of VTA DA neurons. An adaptive level of firing by VTA DA neurons results in adaptive DA release on to NAc MSNs. Despite appetitive behavior leading to an incentive stimulus being processed as primarily aversive by BA A and R projecting to NAc D2R- and D1R-MSNs, respectively: phasic DA release is adaptive and incentive motivation is high. BA basal amygdala, R glutamate reward neuron, A glutamate aversion neuron, NAc nucleus accumbens, D1R medium spiny neuron expressing dopamine receptor 1, D2R medium spiny neuron expressing dopamine receptor 2, VP ventral pallidum, VTA ventral tegmental area, RMTg rostro-medial tegmentum.

In summary, the current mouse study provides evidence for some specific neural and behavioral effects of GPR52 inverse agonism in the basal and stressed states. Taken together, this provides preclinical validation of this mechanism-of-action for amelioration of reward processing dysfunction. GPR52-IA reinstatement of adaptive phasic DA activity in response to effortful behavior resulting in an incentive stimulus, mediated by the NAc D2R-MSN indirect pathway of VTA DA neuron regulation, could be a much-needed efficacious treatment for major neuropsychiatric pathologies such as anhedonia and apathy.

Data availability

All source data underlying the graphs for behavioral and fibre photometry data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

The Matlab code that was used to process and analyze the fibre photometry data is available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Admon R, Pizzagalli DA. Dysfunctional reward processing in depression. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;4:114–8.

Husain M, Roiser JP. Neuroscience of apathy and anhedonia: a transdiagnostic approach. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19:470–84.

Pizzagalli DA. Depression, stress, and anhedonia: toward a synthesis and integrated model. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:393–423.

Kaiser S, Lyne J, Agartz I, Clarke M, Mørch-Johnsen L, Faerden A. Individual negative symptoms and domains—relevance for assessment, pathomechanisms and treatment. Schizophr Res. 2017;186:39–45.

Pelizza L, Ferrari A. Anhedonia in schizophrenia and major depression: state or trait? Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2009;8:22.

Zhao QF, Tan L, Wang HF, Jiang T, Tan MS, Tan L, et al. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:264–71.

Pagonabarraga J, Kulisevsky J, Strafella AP, Krack P. Apathy in Parkinson’s disease: clinical features, neural substrates, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:518–31.

Treadway MT. The neurobiology of motivational deficits in depression-an update on candidate pathomechanisms. Curr Top Behav. Neurosci. 2016;27:337–55.

Treadway MT, Zald DH. Parsing anhedonia: translational models of reward-processing deficits in psychopathology. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22:244–9.

Cuthbert BN. The role of RDoC in future classification of mental disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2020;22:81–85.

Morris SE, Sanislow CA, Pacheco J, Vaidyanathan U, Gordon JA, Cuthbert BN. Revisiting the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Med. 2022;20:220.

Berridge KC, Robinson TE. Parsing reward. TINS. 2003;26:507–13.

Salamone JD, Correa M, Yohn S, Lopez Cruz L, San Miguel N, Alatorre L. The pharmacology of effort-related choice behavior: dopamine, depression, and individual differences. Behav Process. 2016;127:3–17.

Treadway MT, Bossaller N, Shelton RC, Zald DH. Effort-based decision-making in major depressive disorder: a translational model of motivational anhedonia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121:553–8.

Vrieze E, Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Hermans D, Pizzagalli DA, Sienaert P, et al. Dimensions in major depressive disorder and their relevance for treatment outcome. J Affect Disord. 2014;155:35–41.

Wang S, Leri F, Rizvi SJ. Anhedonia as a central factor in depression: neural mechanisms revealed from preclinical to clinical evidence. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Bol Psychiatry. 2021;110:110289.

Knutson B, Westdorp A, Kaiser E, Hommer D. FMRI visualization of brain activity during a monetary incentive delay task. Neuroimage. 2000;12:20–27.

Arrondo G, Segarra N, Metastasio A, Ziaudden H, Spencer J, Reinders NR, et al. Reduction in ventral striatal activity when anticipating a reward in depression and schizophrenia: a replicated cross-diagnostic finding. Front Psychol 2015; 6:128010.3389/fpsyg.2015.01280.

Pizzagalli DA, Holmes AJ, Dillon DG, Goetz EL, Birk JL, Bogdan JL, et al. Reduced caudate and nucleus accumbens response to rewards in unmedicated individuals with major depressive disorder. AJ Psychiatry. 2009;166:702–10.

Stringaris A, Vidal-Ribas Belil P, Artiges E, Lemaitre H, Gollier-Briant F, Wolke S, et al. The brain’s response to reward anticipation and depression in adolescence: dimensionality, specificity, and longitudinal predictions in a community-based sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:1215–23.

Berridge KC, Robinson TE. What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Res Rev. 1998;28:309–69.

Soares-Cunha C, Coimbra B, Sousa N, Rodrigues AJ. Reappraising striatal D1- and D2-neurons in reward and aversion. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;68:370–86.

Yang H, de Jong JW, Tak Y, Peck J, Bateup HS, Lammel S. Nucleus accumbens subnuclei regulate motivated behavior via direct inhibition and disinhibition of VTA dopamine subpopulations. Neuron. 2018;97:434–449.e434.

Pardo-Garcia TR, Garcia-Keller C, Penaloza T, Richie CT, Pickel J, Hope BT, et al. Ventral pallidum is the primary target for accumbens D1 projections driving cocaine seeking. J Neurosci. 2019;39:2041–51.

Hjelmstad GO, Xia Y, Margolis EB, Fields HL. Opioid modulation of ventral pallidal afferents to ventral tegmental area neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:6454–9.

Jhou TC, Geisler S, Marinelli M, Degarmo BA, Zahm DS. The mesopontine rostromedial tegmental nucleus: a structure targeted by the lateral habenula that projects to the ventral tegmental area of Tsai and substantia nigra compacta. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513:566–96.

Kaufling J, Veinante P, Pawlowski SA, Freund-Mercier MJ, Barrot M. Afferents to the GABAergic tail of the ventral tegmental area in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513:597–621.

Pryce CR, Azzinnari D, Spinelli S, Seifritz E, Tegethoff M, Meinlschmidt G. Helplessness: a systematic translational review of theory and evidence for its relevance to understanding and treating depression. Pharm Ther. 2011;132:242–67.

Adamcyzk I, Kukelova D, Just S, Giovannini R, Sigrist H, Amport R, et al. Somatostatin receptor 4 agonism normalizes stress-related excessive amygdala glutamate release and Pavlovian aversion learning and memory in rodents. Biol Psychiatry: Glob Open Sci. 2022;2:470–9.

Kukelova D, Bergamini G, Sigrist H, Seifritz E, Hengerer B, Pryce CR. Chronic social stress leads to reduced gustatory reward salience and effort valuation in mice. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:1–14.

Madur L, Ineichen C, Bergamini G, Greter A, Poggi G, Cuomo-Haymour N, et al. Stress deficits in reward behaviour are associated with and replicated by dysregulated amygdala-nucleus accumbens pathway function in mice. Commun Biol. 2023;6:422.

Münster A, Sommer S, Kúkeľová D, Sigrist H, Koros E, Deiana S, et al. Effects of GPR139 agonism on effort expenditure for food reward in rodent models: evidence for pro-motivational actions. Neuropharmacology. 2022;213:109078.

Zhang C, Dulinskas R, Ineichen C, Greter A, Sigrist H, Li Y, et al. Chronic stress deficits in reward behaviour co-occur with low nucleus accumbens dopamine activity during reward anticipation specifically. Commun Biol. 2024;7:966.

Ali S, Wang P, Murphy RE, Allen JA, Zhou J. Orphan GPR52 as an emerging neurotherapeutic target. Drug Discov today. 2024;29:103922.

Komatsu H, Maruyama M, Yao S, Shinohara T, Sakuma K, Imaichi S, et al. Anatomical transcriptome of G protein-coupled receptors leads to the identification of a novel therapeutic candidate GPR52 for psychiatric disorders. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90134.

Lin X, Li M, Wang N, Wu Y, Luo Z, Guo S, et al. Structural basis of ligand recognition and self-activation of orphan GPR52. Nature. 2020;579:152–7.

Martin AL, Steurer MA, Aronstam RS. Constitutive activity among orphan class-A G protein coupled receptors. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0138463.

Spark DL, Mao M, Ma S, Sarwar M, Nowell CJ, Shackleford DM, et al. In the loop: extrastriatal regulation of spiny projection neurons by GPR52. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11:2066–76.

Sun F, Zeng J, Jing M, Zhou J, Feng J, Owen SF, et al. A genetically encoded fluorescent sensor enables rapid and specific detection of dopamine in flies, fish, and mice. Cell. 2018;174:481–96.

Azzinnari D, Sigrist H, Staehli S, Palme R, Hildebrandt T, Leparc G, et al. Mouse social stress induces increased fear conditioning, helplessness and fatigue to physical challenge together with markers of altered immune and dopamine function. Neuropharmacology. 2014;85:328–41.

Sigrist H, Hogg DE, Senn A, Pryce CR. Mouse model of chronic social stress-induced excessive pavlovian aversion learning-memory. Curr Protoc. 2024;4:e1008.

Ineichen C, Greter A, Baer M, Sigrist H, Sautter E, Sych Y, et al. Basomedial amygdala activity in mice reflects specific and general aversion uncontrollability. Eur J Neurosci. 2020;55:2435–54.

Poggi G, Bergamini G, Dulinskas R, Madur L, Greter A, Ineichen C, et al. Engagement of basal amygdala-nucleus accumbens glutamate neurons in the processing of rewarding or aversive social stimuli. Eur J Neurosci. 2024;59:996–1015.

Ineichen C, Sigrist H, Spinelli S, Lesch K-P, Sautter E, Seifritz E, et al. Establishing a probabilistic reversal learning test in mice: evidence for the processes mediating reward-stay and punishment-shift behaviour and for their modulation by serotonin. Neuropharmacol. 2012;63:1012–21.

Liu C, Bonaventure P, Lee G, Nepomuceno D, Kuei C, Wu J, et al. GPR139, an orphan receptor highly enriched in the habenula and septum, is activated by the essential amino acids L-tryptophan and L-phenylalanine. Mol Pharm. 2015;88:911–25.

Matsuo A, Matsumoto S, Nagano M, Masumoto KH, Takasaki J, Matsumoto M, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel Gq-coupled orphan receptor GPRg1 exclusively expressed in the central nervous system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:363–9.

Chang C-H, Grace AA. Amygdala-ventral pallidum pathway decreases dopamine activity after chronic mild stress in rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76:223–30.

Tye KM, Mirzabekov JJ, Warden MR, Ferenczi EA, Tsai H-C, Finkelstein J, et al. Dopamine neurons modulate neural encoding and expression of depression-related behaviour. Nature. 2013;493:537–43.

Floresco SB, West AR, Ash B, Moore H, Grace AA. Afferent modulation of dopamine neuron firing differentially regulates tonic and phasic dopamine transmission. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:968–73.

Mohebi A, Pettibone JR, Hamid AA, Wong JT, Vinson LT, Patriarchi T, et al. Dissociable dopamine dynamics for learning and motivation. Nature. 2019;570:65–70.

Beaulieu J-M, Gainetdinov RR. The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. Pharm Rev. 2011;63:182–217.

Shen CJ, Zheng D, Li KX, Yang JM, Pan HQ, Yu XD, et al. Cannabinoid CB(1) receptors in the amygdalar cholecystokinin glutamatergic afferents to nucleus accumbens modulate depressive-like behavior. Nat Med. 2019;25:337–49.

Faget L, Oriol L, Lee WC, Zell V, Sargent C, Flores A, et al. Ventral pallidum GABA and glutamate neurons drive approach and avoidance through distinct modulation of VTA cell types. Nat Commun. 2024;15:4233.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Björn Henz and Alex Oseil for animal caretaking, Yulong Li for provision of GRABDA sensor viral vectors, and to Klaus Bornemann for discussion and support.

Funding

This research was funded by the Chinese Scholarship Council (PhD fellowship to CZ), Swiss National Science foundation (31003A_179381 to CRP) and by a Boehringer-Ingelheim collaboration grant (to CRP). BH, RFK, PM, AO and MvH are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co KG. CRP has received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co KG. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CZ designed the study, acquired, analyzed and interpreted data and drafted the manuscript; DK acquired and analyzed data; HS oversaw animals and equipment and acquired data; BH conceived and designed the study and drafted the manuscript; RFK acquired, analyzed and interpreted data and drafted the manuscript; PM acquired, analyzed and interpreted data and drafted the manuscript; AO designed the study, acquired, analyzed and interpreted data and drafted the manuscript; MvH conceived and designed the study, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript; CRP conceived and designed the study, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Kúkeľová, D., Sigrist, H. et al. Orphan receptor-GPR52 inverse agonist efficacy in ameliorating chronic stress-related deficits in reward motivation and phasic accumbal dopamine activity in mice. Transl Psychiatry 14, 363 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-024-03081-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-024-03081-w