Abstract

Individuals with non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) may be particularly vulnerable to social media exposure, yet the extent to which this vulnerability is linked to altered reward processing remains unclear. To address this gap, we investigated social media-related reward processing in NSSI by recruiting ninety-one young women, divided into three groups: a clinical group (NSSI with borderline personality disorder), a subclinical group (NSSI without co-occurring disorders), and a healthy control group. While undergoing functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), participants received positive and negative comments on their own Instagram photos in a naturalistic task simulating real-life social media interactions. Clinical participants rated positive comments as less pleasant and negative comments as more unpleasant than controls. Coherently, they showed blunted activation in core reward regions such as the nucleus accumbens, caudate, and medial frontal cortex when receiving positive vs negative feedback. Subclinical participants reacted similarly to clinical participants to negative feedback but similarly to controls to positive feedback and presented intermediate activation in most regions, bridging the pattern observed in controls and patients. Results highlight reward system dysfunction as central to NSSI pathology, with both clinical and subclinical groups showing altered processing of social media-based feedback. Subclinical participants showed selective vulnerability to negative feedback, while clinical participants showed impaired sensitivity to both positive and negative feedback. These findings reflect a continuum of severity mapped on the reward system, highlighting potential intervention targets and emphasizing the need to address social media interactions in NSSI treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), defined as the deliberate, self-inflicted destruction of one’s body tissue without suicidal intent [1, 2], is an increasingly prevalent and concerning phenomenon, particularly among adolescents and young adults [3]. Global prevalence estimates in youth range from 18% to 23%, with higher rates in females [4] Extensive research indicates that NSSI is associated with a range of negative physical and psychological outcomes and is one of the strongest risk factors for suicidal ideation and attempt [1, 2, 5,6,7,8,9,10]. Beyond the personal burden, NSSI also entails substantial health care and economic costs [11], becoming a pressing concern for public health and a priority for research [12].

Social factors are central to the onset and maintenance of NSSI. Individuals struggling with NSSI often perceive low social support [13] and experience impaired social functioning, including difficulties in establishing and maintaining interpersonal relationships [14, 15]. Accordingly, a significant portion of individuals with NSSI endorse interpersonal motives, such as communicating distress or seeking support [16], and interpersonal conflicts are consistently identified as proximal triggers for NSSI episodes [17,18,19]. However, these findings stem from studies analysing offline social interactions, while emerging evidence suggests that the social dynamics in online environments, particularly in social media platforms, may also influence the risk and maintenance of NSSI [20,21,22].

Over the past two decades, social media has become a normative part of everyday life, even more so for young people [23, 24]. Individuals with NSSI are particularly vulnerable, often turning to social media to seek connection and support [25]. However, increased exposure to social media can also heighten the risk of exposure to cyberbullying [26], unfavorable social comparisons [27], and self-harm content [28, 29], all of which could be potential triggers for NSSI [30]. Indeed, exposure to social media platforms has been significantly associated with an increased risk of NSSI among adolescents [31, 32], both in psychiatric [33, 34] and community samples [35, 36], particularly among women [31, 37]. Nevertheless, the neural mechanisms underlying these associations remain unknown.

Growing evidence suggests that aspects of social media use, such as the opportunity to receive social approval through Likes or positive comments, activate the brain’s reward system [38,39,40,41]. This system is associated with processing pleasure and motivational stimuli and is formed by structures like the ventral tegmental area (VTA), the ventral (e.g., nucleus accumbens; NAcc) and dorsal (e.g., caudate nucleus and putamen) striatum, and the ventro-medial prefrontal (e.g., medial orbitofrontal; mOFC) cortex [42]. Activation in these regions is often experienced as a positive emotion that reinforces the action that triggered it [43], therefore the positive emotions that may result from receiving Likes and positive comments on social media can foster addictive tendencies [44]. Young people who recurrently engage in NSSI may be particularly vulnerable, as they tend to use social media as a substitute for natural social rewards [45, 46], and already display addictive behavioral patterns (for NSSI conceptualized as an addiction, see [47, 48]). However, no previous study has examined how social media exposure may affect the reward system in youth with NSSI.

To address this gap, we designed a novel social reward task that approximates real-life social interactions on social media by using personalized stimuli derived from participants’ own Instagram profiles. This highly ecological, innovative approach was applied to a large sample of young women divided into three groups with different levels of clinical severity: (i) a clinical group with NSSI and borderline personality disorder (BPD), (ii) a subclinical group with NSSI but without BPD or other disorders, and (iii) a healthy control group. Given prior research suggesting that NSSI is associated with reward system alterations independently of BPD [49, 50], we predicted that the three groups would show distinct patterns of neural activation when processing social rewards vs social punishments. More specifically, we hypothesized that participants in the subclinical group would show intermediate reward-related activity, bridging the pattern observed in healthy controls and BPD patients, which might reflect a continuum of severity. Additionally, we hypothesized that reward-related neural activity would be differentially associated with Instagram addiction in each group, providing a more nuanced understanding of the complex interaction between social media use, reward processing, and NSSI.

Materials and methods

Participants

We recruited 91 participants, divided into three groups. Two groups presented recurrent and recent NSSI (engagement in NSSI on ≥ 5 days in the past year), but one was clinical and the other subclinical. The clinical group (NSSI + BPD) included 31 women with BPD, recruited from the Hospital of Igualada and the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona, Spain), where they were receiving psychological and/or psychiatric treatment. The subclinical group (NSSI) included 27 women without BPD or other psychiatric disorders, recruited from the community, and not receiving psychological or psychiatric treatment in the past two years. The third group was a healthy control group (HC), which included 33 women with no history of NSSI, other psychiatric disorders, or psychological/psychiatric treatment. All participants were women, aged 18–30, with an active Instagram account. General exclusion criteria included psychotic, bipolar, or neurological disorders, substance intoxication/withdrawal, claustrophobia, cognitive impairment, and illiteracy. The recruitment process is shown in Fig. 1.

Participants in the three groups were matched by age and social media use (see Table 1 for sociodemographic, clinical and NSSI characteristics of the sample). We specifically recruited an entirely female sample because BPD [51] and NSSI [52] are more commonly expressed in women than men, and because the negative effects of social media on NSSI are more pronounced in females [31]. All participants underwent the MINI- International Neuropsychiatric Interview [53] and the Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines-Revised (DIB-R) [54] to confirm (for the NSSI + BPD group) or discard (for the NSSI and HC group) current diagnosis of BPD and/or other psychiatric disorders.

All participants signed an informed consent form and received monetary compensation for their participation in the study. All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee at Bellvitge University Hospital [PR074/23 (CSA PR9/2023)] and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures and procedures

Self-report

Participants first completed the Borderline Personality Questionnaire (BPQ [55]), the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21 [56]) and the Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Disorder Scale (NSSID-S [57]) to assess clinical symptoms and NSSI features. Then, they completed the Instagram Addiction Scale (IAS [58]) and a series of other questionnaires related to social functioning (see supplementary material).

Experimental paradigm

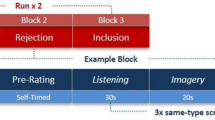

Participants took part in an fMRI-compatible Social Incentive Delay (SID) task, recently developed to investigate social media-related reward processing [59]. This task is a social variant of the well-established Monetary Incentive Delay task (MID) [60,61,62] and was previously used with a healthy sample in an electroencephalography study [59]. Upon recruitment, participants were informed that the study aimed to examine the impact of social media on mental health. After consenting, participants authorized the researcher to follow their personal Instagram account and select 15 of their photos (avoiding selfies, pets, or other people’s photos) to be shown during the experiment, along with other participants’ photos, simulating an Instagram-like feed. Each photo would receive four comments, which participants were told were from other young volunteers who either “liked” or “disliked” the images. However, the comments were, in fact, written by the researchers and most were intentionally generic, including emojis for realism, while others were specifically tailored to participants’ photos to enhance credibility.

The experiment took place approximately one week after authorization, allowing participants time to believe their photos had been genuinely evaluated. The task was composed of 120 trials across four runs, totaling about 35 min. During each trial, a photo from either the participant’s or another participant’s Instagram account was displayed, followed by a delay and a visual cue indicating the trial condition: reward (with a circle) or punishment (with a square). A reward cue meant that participants could earn a positive comment, while a punishment cue meant they could avoid a negative comment based on their performance. Then, a target (white square) appeared, and participants responded as quickly as possible to “win”. Reaction times determined the outcome, and dynamic timing adjustments ensured a 60% “win” rate.

Feedback was given in two phases. In Feedback Phase 1, participants were informed whether they won or lost, setting the stage for further feedback. In reward trials, a Like with 1 indicated a win and the receipt of a positive comment, while a Like with 0 signified a loss and the omission of a positive comment. In punishment trials, a Dislike with 0 indicated a win and the omission of a negative comment, and a Dislike with 1 signaled a loss and the receipt of a negative comment. After a brief delay, Feedback Phase 2 displayed a speech bubble with the corresponding comment or left it empty if no comment was warranted. In addition, 8 catch trials were introduced semi-randomly throughout the experiment (2 catch trials per run; approximately every 11–13 trials to avoid predictability), where instead of responding to the target, participants had to select the cue presented at the beginning of the trial (see Fig. 2 and supplementary information about details on the paradigm).

A Reward trials. B Punishment trials. C Catch trials. D Liking ratings for positive comments as a function of Photo-Type and Group. E Disliking ratings for negative comments as a function of Photo-Type and Group. Notice that the NSSI group liked the positive comments as much as the HC group but disliked the negative comments as much as the NSSI + BPD group.

After the fMRI task, participants rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 10 (very much) how much they liked receiving Likes and positive comments, and how much they disliked receiving Dislikes and negative comments on both their own and others’ photos. After completing all post-scanner questions, participants were fully debriefed and thanked for their participation. During debriefing, participants were asked to verify whether they believed they were receiving real feedback or whether they suspected that they had been deceived. All participants believed the cover story.

Statistical analysis

Three participants were excluded from the original sample due to poor data quality. Specifically, one was excluded because she failed multiple attention checks (e.g., 6 out of 8 catch trials), another because her mean reaction time was significantly slower than everyone else’s ( > 3 SD above the group mean), and the third because of excessive head movement in the scanner (18.15 mm). All other participants met more stringent head motion criteria ( ≤ 4.5 mm). The final sample included in the analysis consisted of 32 participants in the HC group, 27 in the NSSI group, and 29 in the NSSI + BPD group (total N = 88).

Behavioral data

A three-way mixed ANOVA with Photo Type (Own vs Other) and Cue Type (Reward vs Punishment) as within-subjects factors and Group (HC vs NSSI vs NSSI + BPD) as between-subjects factor was used to analyze each of the following dependent measures: mean reaction times, win rates, and accuracy on catch trials. Trials with exceedingly short or long reaction times ( ± 3 SD from each participant’s mean RT) were removed [63].

In addition, a two-way mixed ANOVA with Photo Type (Own vs Other) as within-subjects factor and Group (HC vs NSSI vs NSSI + BPD) as between-subjects factor was employed to analyze post-scanner ratings. All p-values reported are Greenhouse–Geisser corrected, and effect sizes are reported as partial eta squared values (η2p). Further simple effect analyses were conducted if ANOVAs displayed a significant interaction. All statistical analyses were conducted in R (v4.2.1) [64].

fMRI data

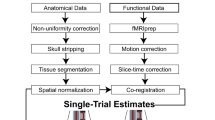

Image acquisition and preprocessing

Blood oxygen-level dependent fMRI was performed on a 1.5 T Phillips Achieva scanner at Hospital Universitari d’ Igualada, using an echo-planar sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 3 s, echo time (TE) = 50 milliseconds, 163 volumes for each run (first 4 volumes discarded to ensure magnetization steady-state), 25 oblique slices per volume, (slice thickness = 4 mm, 112 × 112 matrix). Slices were collected consecutively, using ascending slice acquisition. The fMRI data was preprocessed and analyzed with Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM12) using standard procedures.

fMRI modeling and analysis

Differences between groups in the Win vs Loss contrast at Feedback Phase 1 were initially studied at the whole-brain level. Then, interactions between Group, Outcome, and Cue Type were modelled in a full factorial design and studied in pre-determined regions of interest (ROI), such as the left and right NAcc and mOFC (complete description of the preprocessing and analysis can be found in the supplementary material). To control for medication in BPD patients, we repeated all analyses with medication load as a covariate (see supplementary material for this variable).

Results

Self-report

Between-group differences in self-report variables related to clinical severity, NSSI and social media use are summarized in Table 1 (for measures relating to social functioning, see Table S1 in supplementary material). As expected, the NSSI group scored higher than the HC group and lower than the NSSI + BPD group on borderline symptomatology (BPQ) and depression, anxiety and stress (DASS) symptoms, confirming its subclinical status. In addition, the three groups did not differ in self-reported measures of Instagram addiction or weekly social media use (see Table 1), suggesting that any potential differences in brain activity cannot be attributed to differences in social media addiction between groups.

Behavioral

Participants liked the positive comments (F(1,85) = 77.47, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.47, Fig. 2D) and disliked the negative ones (F(1,85) = 30.85, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.26, Fig. 2E) significantly more for their own photos than for others’. In addition, ratings of both positive (F(2,85) = 3.81, p = 0.026, η2p = 0.08) and negative comments (F(2,85) = 3.86, p = 0.025, η2p = 0.08) varied significantly by group.

Specifically, the NSSI + BPD group rated the positive comments as significantly less pleasant than the HC group, (t(59) = −2.87, p = 0.006), whereas the NSSI group did not significantly differ from the HC group, (t(57) = −1.03, p = 0.306). However, with regards to the negative comments, both the NSSI (t(57) = 2.56, p = 0.013) and NSSI + BPD groups (t(59) = 2.12, p = 0.038) rated them as significantly more unpleasant than the HC group, with no significant difference between the two NSSI groups (t(54) = −0.50, p = 0.617). Ratings for Likes and Dislikes followed a similar pattern (see supplementary material for all the behavioral results).

Importantly, the three groups did not significantly differ on accuracy on catch trials (F(2,85) = 1.65, p = 0.198, η2p = 0.04). Average percent accuracy exceeded 80% in all groups (HC: 89.5 ± 25.8; NSSI: 92.1 ± 22.6; NSSI + BPD: 84.4 ± 30.4), suggesting that any potential differences in brain activity cannot be attributed to attention differences between groups.

FMRI

Whole-brain analysis - win vs loss contrast (own photos)

We focused the analysis on participants’ own photos, but similar results were found when considering all photos (own and others, see supplementary information). As shown in Table 2, the one-way ANOVA of the win vs loss contrast for own photos revealed significant group differences in key regions of the reward network, such as the NAcc, the caudate, the medial frontal cortex, the hippocampus, and the anterior insula. Post-hoc comparisons between groups are shown in Fig. 3. Results revealed higher activity in the HC compared to the NSSI + BPD group in most of the studied regions, with the NSSI group presenting intermediate values (see supplementary results for complete description). Importantly, these results were maintained even when controlling for medication load and even when using alternative significance and cluster extent thresholds (see supplementary material).

Neural activations are shown at p < 0.001 for demonstrational purposes, and voxels that survive the FWE correction (p < 0.05) are overlaid and shown in yellow. Notice the pattern in key regions of the reward network (NAcc and Caudate); the contrast estimate decreases as clinical severity increases. Note. p < 0.1 *, p < 0.05**, p < 0.01 ***, p < 0.001 ****.

Region of interest (ROI) analysis

The full factorial design for participants’ own photos revealed a significant 3-way Group X Cue X Outcome interaction in the right NAcc, F(2,85) = 3.93, p = 0.023, η2p = 0.08, and the right mOFC ROIs, F(2,85) = 3.70, p = 0.028, η2p = 0.08, but not in the left NAcc, F(2,85) = 0.59, p = 0.555, η2p = 0.01, or left mOFC ROIs, F(2,85) = 2.11, p = 0.127, η2p = 0.01, suggesting that this triple interaction effect may be right-lateralized. To dissect the triple interaction, we conducted follow-up 2-way Group X Outcome interactions at each level of cue (reward vs punishment). For reward conditions, the Group X Outcome interaction was not significant either in the right mOFC, F(2,85) = 0.79, p = 0.453, η2p = 0.02, or in the right NAcc ROIs, F(2,85) = 1.94, p = 0.150, η2p = 0.04.

However, for punishment conditions, the Group X Outcome interaction was significant in the right mOFC, F(2,85) = 4.78, p = 0.011, η2p = 0.10, and marginally significant in the right NAcc ROIs, F(2,85) = 2.38, p = 0.093, η2p = 0.05. As shown in Fig. 4, win and loss outcomes in the punishment conditions evoked differential activations in the right NAcc and right mOFC in the three groups, with the HC and NSSI + BPD groups exhibiting a complete opposite pattern, and the NSSI group maintaining an intermediate profile between the HC and NSSI + BPD groups. Specifically, for the HC group, activity was significantly higher for wins relative to losses both in the right NAcc (t(31) = 2.04, p = 0.049) and the right mOFC (t(31) = 2.22, p = 0.034), whereas for the NSSI group, activity did not significantly differ between wins and losses in neither of the two regions (right NAcc: t(26) = 0.34, p = 0.735; right mOFC: t(26) = 0.59, p = 0.560). For the NSSI + BPD group, the pattern was reversed, such that activity was lower for wins relative to losses (significant at right mOFC: t(28) = −2.22, p = 0.034, but not right NAcc: t(28) = −0.99, p = 0.327).

Finally, for others’ photos, this 3-way interaction effect was not significant in any of the studied areas (F(2,85) ≤ 1.58, p > 0.1).

Correlations

As shown in Fig. 5, the own win vs loss contrast estimate at the NAcc was negatively correlated with Instagram addiction scores in the NSSI (right: r = −0.40, p = 0.041; left: r = −0.50, p = 0.008) and NSSI + BPD groups (significant at right: r = −0.49, p = 0.012; but not left: r = −0.16, p = 0.440), but not in the HC group (right: r = 0.04, p = 0.810; left: r = 0.14, p = 0.440). It also correlated with DASS scores, but only in the clinical NSSI + BPD group (right: r = −0.34, p = 0.075; left: r = −0.43, p = 0.022). BPQ scores did not correlate with the win vs loss contrast estimates at the left or right NAcc in any group, p > 0.10.

Discussion

This study examined the impact of social media exposure on the reward system in young women with NSSI. Using a novel social reward task that uses naturalistic stimuli to simulate interactions on Instagram, we found that participants with NSSI showed altered social reward processing compared to healthy controls. On the one hand, the clinical group (NSSI + BPD) exhibited blunted activity in key regions of the reward network (e.g., NAcc, medial frontal cortex, caudate) when receiving social rewards vs punishments, as well as a complete opposite pattern in the right mOFC and NAcc when processing social punishments. On the other hand, the subclinical participants (NSSI group) exhibited an intermediate profile between the HC and NSSI + BPD groups across all fMRI analyses, indicating a continuum of clinical severity mapped onto the reward system. Finally, the neural signal in the NAcc was negatively associated with Instagram addiction in the NSSI groups but not in the HC group, suggesting that problematic social media use in NSSI may be related to altered neural processing of social rewards.

Blunted reward-system activity in the NSSI + BPD group when receiving social rewards vs punishments is consistent with prior research indicating an impaired discrimination between positive and negative social situations [65] and a negative bias in decoding social rewards in BPD [66]. Indeed, previous studies suggest that BPD patients feel excluded even when they are socially included [67, 68] and show attenuated positive affect in response to positive social feedback [69,70,71].

Complementarily, the ROI analysis revealed that the blunted reward-system activity observed in the whole-brain analysis for the NSSI + BPD group may result both from reduced activation to wins and increased activation to losses. In this group, increased activity in the right mOFC and NAcc when receiving negative comments (see Fig. 4) and higher ratings of these comments as unpleasant (see Fig. 2E) may suggest that negative social feedback is more engaging for this population. This aligns with previous studies showing increased NAcc activity for highly engaging-highly unpleasant experiences, such as near-misses in slot machine games [72], supporting the role of this area in invigorating behaviours with unpleasant outcomes. We propose that this aberrant recruitment of reward regions in response to negative social feedback may underlie social cognition deficits in BPD, including attentional bias towards negative stimuli [73] and updating of self-evaluations [74] and expectations of social acceptance [75] with negative vs positive social feedback. More importantly, this heightened activation may reinforce, rather than diminish, behaviours that lead to unpleasant social outcomes, potentially explaining why these patients struggle to learn from negative social feedback [76].

Interestingly, current fMRI results reveal a continuum of activation in reward-related regions (e.g., NAcc and caudate), covering the spectrum from HC to NSSI + BPD, with the NSSI group displaying an intermediate activation that bridges the pattern observed in the other two groups. Notably, while subclinical NSSI participants showed intermediate activation in the NAcc and the caudate, they displayed similar activation to the NSSI + BPD group in regions related to negative feedback processing, such as the hippocampus and anterior insula [77, 78] (see Fig. 3) and similar activation to the HC group in regions related to positive feedback processing (e.g., medial frontal cortex [79]). This may suggest that subclinical participants with NSSI may have an impaired sensitivity to negative social feedback, while their sensitivity to positive social feedback remains intact. Behavioral data further support this notion, with the subclinical NSSI group rating the negative comments as unpleasant as the NSSI + BPD group, but the positive comments as pleasant as the HC group (see Fig. 2D & E). Finally, self-report data further support this selective vulnerability to negative feedback in subclinical participants, with the NSSI group reporting similar social punishment sensitivity as the NSSI + BPD group, and similar social reward sensitivity as the HC group (see Table S1).

Taken together, our findings help better characterize the social reward dysfunction associated with subclinical and clinical NSSI, refining our understanding of NSSI behaviours with and without comorbid BPD and helping to develop better-targeted interventions for each group. While the cross-sectional nature of our study can only allow us to describe the neural characteristics of the three groups at a single time point, our findings may serve as a basis for future longitudinal studies to explore whether there is a linear developmental trajectory from NSSI to BPD and whether the neural alterations observed in the NSSI group represent precursors to those seen in BPD. Given prior research suggesting that NSSI and BPD might represent a developmental continuum [65, 80, 81], starting with an increased sensitivity to negative social feedback in NSSI that may generalize to positive social feedback in BPD [81], it may be interesting for longitudinal studies to use our fMRI paradigm to identify whether and which individuals in the subclinical group may eventually develop BPD.

Conclusively, this study used a more naturalistic experimental task than previous studies, providing better insight into how a healthy brain functions during real-life social media use and how this may be altered in individuals with repetitive NSSI behaviours. A potential limitation is that the negative comments we used were of moderate intensity due to ethical concerns, potentially making them less harsh than those encountered in real-life scenarios. Negative comments in real-life social media interactions may lead to stronger responses than those our study was able to elicit, particularly among the NSSI groups. Also, since our study focused on women and used Instagram-derived stimuli, findings may not generalize to men or other platforms (e.g., Tik-Tok). Finally, although we controlled for medication load in the fMRI analyses, including BPD outpatients on psychotropic medication with potential comorbid mental disorders (e.g., mood disorders) could be a limitation.

Despite these limitations, our naturalistic design and inclusion of three groups (for the only three-group studies to date, see [49, 50, 81, 82]) make our study a pioneer in the field and a key step in identifying social reward alterations linked to NSSI, independently of BPD. Results reflect a continuum of severity mapped onto the reward system, with social media-related reward processing alterations found in both clinical and subclinical populations with NSSI. Importantly, these neural alterations were linked to depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms in the NSSI + BPD group, and to problematic social media use in both NSSI groups, but not in the HC group. While these associations between NAcc activation and Instagram addiction severity are unique to the NSSI groups, this is not sufficient to support that NSSI may serve as a vulnerability marker for social media addiction. Indeed, these specific neural associations in the NSSI groups may also be due to difficulties in emotion regulation present in both NSSI [83] and social media addiction [84]. Taken together, findings support dimensional approaches that emphasize the continuum of mental health and illness (e.g., Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project [85]), and they offer a more nuanced understanding of the impact of social media on mental health.

Data availability

Data related to this manuscript may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Nock MK. Self-Injury. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:339–63. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258.

Vega D, Sintes A, Fernández M, Puntí J, Soler J, Santamarina P, et al. Revisión y actualización de la autolesión no suicida: ¿quién, cómo y por qué? TT - Review and update on non-suicidal self-injury: who, how and why? Actas esp Psiquiatr 2018;46:146–155.

Dick B, Ferguson BJ. Health for the world’s adolescents: a second chance in the second decade. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:3–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.260.

Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, St John NJ. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44:273–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12070.

Ammerman BA, Burke TA, Alloy LB, McCloskey MS. Subjective pain during NSSI as an active agent in suicide risk. Psychiatry Res. 2016;236:80–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.12.028.

Joiner T Why people die suicide. 2005..

Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp J, Eckenrode J, Purington A, Baral Abrams G, Barreira P, et al. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a gateway to suicide in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:486–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.010.

Horwitz AG, Czyz EK, King CA. Predicting future suicide attempts among adolescent and emerging adult psychiatric emergency patients. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44:751–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2014.910789

Klonsky E, May AM, Glenn CR. The relationship between nonsuicidal self-injury and attempted suicide: Converging evidence from four samples. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:231–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030278.

Hamza CA, Stewart SL, Willoughby T. Examining the link between nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: a review of the literature and an integrated model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32:482–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.05.003.

Kinchin I, Doran CM, Hall WD, Meurk C. Understanding the true economic impact of self-harming behaviour. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:900–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30411-X.

Moran P, Chandler A, Dudgeon P, Kirtley OJ, Knipe D, Pirkis J, et al. The Lancet Commission on self-harm. Lancet. 2024;404:1445–92.

Mendez I, Sintes A, Pascual JC, Puntí J, Lara A, Briones-Buixassa L, et al. Borderline personality traits mediate the relationship between low perceived social support and non-suicidal self-injury in a clinical sample of adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2022;302:204–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.065.

Ammerman BA, Sorgi KM, Fahlgren MK, Puhalla AA, McCloskey MS. An experimental examination of interpersonal problem-solving in nonsuicidal self-injury: a pilot study. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;144:146–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.005.

Turner BJ, Wakefield MA, Gratz KL, Chapman AL. Characterizing interpersonal difficulties among young adults who engage in nonsuicidal self-injury using a daily diary. Behav Ther. 2017;48:366–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.07.001.

Taylor PJ, Jomar K, Dhingra K, Forrester R, Shahmalak U, Dickson JM. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. J Affect Disord. 2018;227:759–69.

Hepp J, Carpenter RW, Freeman LK, Vebares TJ, Trull TJ. The environmental, interpersonal, and affective context of nonsuicidal self-injury urges in daily life. Personal Disord: Theory, Research, Treat. 2021;12:29–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000456.

Turner BJ, Cobb RJ, Gratz KL, Chapman AL. The role of interpersonal conflict and perceived social support in nonsuicidal self-injury in daily life. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016;125:588–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000141.

Snir A, Rafaeli E, Gadassi R, Berenson K, Downey G. Explicit and inferred motives for nonsuicidal self-injurious acts and urges in borderline and avoidant personality disorders. Personal Disord: Theory, Research, Treat. 2015;6:267–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000104.

Marchant A, Hawton K, Stewart A, Montgomery P, Singaravelu V, Lloyd K, et al. A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: The good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181722. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181722.

Twenge JM. Increases in depression, self‐harm, and suicide among U.S. adolescents after 2012 and links to technology use: Possible mechanisms. Psychiatr Res Clin Pract. 2020;2:19–25. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.prcp.20190015.

Moss C, Wibberley C, Witham G. Assessing the impact of Instagram use and deliberate self-harm in adolescents: a scoping review. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2023;32:14–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13055.

Bozzola E, Spina G, Agostiniani R, Barni S, Russo R, Scarpato E, et al. The use of social media in children and adolescents: scoping review on the potential risks. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2022;19:9960. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169960.

Twenge JM, Martin GN, Spitzberg BH Trends in U.S. Adolescents’ Media Use, 1976–2016: The Rise of Digital Media, the Decline of TV, and the (Near) Demise of Print. Psychol Pop Media Cult 2019;8. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000203.

Liu S, Lin MP, Lee YT, Wu JYW, Hu WH, You J. Internet addiction and nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescence: associations with offline and online social support. J Clin Psychol. 2022;78:971–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23264.

Hamm MP, Newton AS, Chisholm A, Shulhan J, Milne A, Sundar P, et al. Prevalence and effect of cyberbullying on children and young people: a scoping review of social media studies. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:770–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0944.

Nesi J, Prinstein MJ. Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking: gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015;43:1427–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0020-0.

Brown RC, Fischer T, Goldwich AD, Keller F, Young R, Plener PL. #cutting: Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) on Instagram. Psychol Med. 2018;48:337–46. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717001751.

Arendt F, Scherr S, Romer D Effects of exposure to self-harm on social media: Evidence from a two-wave panel study among young adults. N Media Soc 2019;21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819850106.

Chen Z, Liao X, Yang J, Tian Y, Peng K, Liu X, et al. Association of screen-based activities and risk of self-harm and suicidal behaviors among young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychiatry Res. 2024;338:115991.

Spínola LG, Calaboiça C, Carvalho IP. The use of social networking sites and its association with non-suicidal self-injury among children and adolescents: a systematic review. J Affect Disord Rep. 2024;16:100781.

Tørmoen AJ, Myhre MØ, Kildahl AT, Walby FA, Rossow I. A nationwide study on time spent on social media and self-harm among adolescents. Sci Rep. 2023;13:19111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46370-y.

Shafi RMA, Nakonezny PA, Romanowicz M, Nandakumar AL, Suarez L, Croarkin PE. Suicidality and self-injurious behavior among adolescent social media users at psychiatric hospitalization. CNS Spectr. 2021;26:275–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852920001108.

Nesi J, Burke TA, Lawrence HR, MacPherson HA, Spirito A, Wolff JC. Online self-injury activities among psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents: prevalence, functions, and perceived consequences. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2021;49:519–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00734-4.

Barthorpe A, Winstone L, Mars B, Moran P. Is social media screen time really associated with poor adolescent mental health? A time use diary study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:864–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.106.

McAllister C, Hisler GC, Blake AB, Twenge JM, Farley E, Hamilton JL. Associations between adolescent depression and self-harm behaviors and screen media use in a nationally representative time-diary study. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2021;49:1623–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-021-00832-x.

Twenge JM, Farley E. Not all screen time is created equal: associations with mental health vary by activity and gender. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56:207–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01906-9.

Meshi D, Morawetz C, Heekeren HR. Nucleus accumbens response to gains in reputation for the self relative to gains for others predicts social media use. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:439. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00439.

Meshi D, Tamir DI, Heekeren HR. The emerging neuroscience of social media. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19:771–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2015.09.004.

Sherman LE, Hernandez LM, Greenfield PM, Dapretto M. What the brain ‘Likes’: neural correlates of providing feedback on social media. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2018;13:699–707. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsy051.

Sherman LE, Payton AA, Hernandez LM, Greenfield PM, Dapretto M. The power of the like in adolescence: effects of peer influence on neural and behavioral responses to social Media. Psychol Sci. 2016;27:1027–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616645673.

Lewis RG, Florio E, Punzo D, Borrelli E The Brain’s Reward System in Health and Disease. In: Adv Exp Med Biol 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81147-1_4.

Pettorruso M, Zoratto F, Miuli A, De Risio L, Santorelli M, Pierotti A, et al. Exploring dopaminergic transmission in gambling addiction: a systematic translational review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;119:481–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.09.034.

Andreassen CS, Billieux J, Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics Z, Mazzoni E, et al. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol Addictive Behav. 2016;30:252–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000160.

Dyson MP, Hartling L, Shulhan J, Chisholm A, Milne A, Sundar P, et al. A systematic review of social media use to discuss and view deliberate self-harm acts. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0155813. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155813.

Seko Y, Lewis SP The self—harmed, visualized, and reblogged: remaking of self-injury narratives on Tumblr. New Media Soc 2018;20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816660783.

Pritchard TR, Fedchenko CA, Lewis SP. Self-injury is my drug: the functions of describing nonsuicidal self-injury as an addiction. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2021;209:628–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001359.

Blasco-Fontecilla H, Fernández-Fernández R, Colino L, Fajardo L, Perteguer-Barrio R, de Leon J. The addictive model of self-harming (non-suicidal and suicidal) behavior. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00008.

Vega D, Ripollés P, Soto À, Torrubia R, Ribas J, Monreal JA, et al. Orbitofrontal overactivation in reward processing in borderline personality disorder: the role of non-suicidal self-injury. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12:217–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-017-9687-x.

Nicolaou S, Pascual JC, Soler J, Ortega G, Marco-Pallarés J, Vega D. Mapping punishment avoidance learning deficits in non-suicidal self-injury in young adults with and without borderline personality disorder: an fMRI study. J Affect Disord. 2025;370:489–98.

Skodol AE Gender-specific etiologies for antisocial and borderline personality disorders? In: Gender and its effects on psychopathology. 2000.

Lutz NM, Neufeld SAS, Hook RW, Jones PB, Bullmore ET, Goodyer IM, et al. Why is non-suicidal self-injury more common in women? mediation and moderation analyses of psychological distress, emotion dysregulation, and impulsivity. Arch Suicide Res. 2023;27:905–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2022.2084004.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. In: J Clin Psychiatry 1998.

Barrachina J, Soler J, Campins MJ, Tejero A, Pascual JC, Álvarez E, et al. Validación de la versión española de la Diagnostic Interview for Bordelines-Revised (DIB-R). Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2004;32:293–8.

Fonseca-Pedrero E, Paino M, Lemos-Giráldez S, Sierra-Baigrie S, González MPGP, Bobes J, et al. Borderline personality traits in nonclinical young adults. J Pers Disord. 2011;25:542–56. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2011.25.4.542.

Arturo BL, Antoni S, Raquel A Psycometric Properties of the Spanish Version of Depression,Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS). Psicothema 2005.

Victor SE, Davis T, Klonsky ED. Descriptive characteristics and initial psychometric properties of the non-suicidal self-injury disorder scale. Arch Suicide Res. 2017;21:265–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2016.1193078.

Kircaburun K, Griffiths MD. Instagram addiction and the Big Five of personality: The mediating role of self-liking. J Behav Addict. 2018;7:158–70. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.15.

Nicolaou S, Vega D, Marco-Pallarés J. Opening the Pandora box: neural processing of self-relevant negative social information. Biol Psychol. 2025;194:108982.

Knutson B, Fong GW, Adams CM, Varner JL, Hommer D. Dissociation of reward anticipation and outcome with event-related fMRI. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3683–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001756-200112040-00016.

Wilson RP, Colizzi M, Bossong MG, Allen P, Kempton M, Abe N, et al. The neural substrate of reward anticipation in health: a meta-analysis of fMRI findings in the monetary incentive delay task. Neuropsychol Rev. 2018;28:496–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-018-9385-5.

Oldham S, Murawski C, Fornito A, Youssef G, Yücel M, Lorenzetti V. The anticipation and outcome phases of reward and loss processing: a neuroimaging meta-analysis of the monetary incentive delay task. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39:3398–418. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24184.

Xu M, Zhang J, Li Z. Social exclusion modulates neural dynamics of monetary and social reward processing in young adult females. Biol Psychol. 2022;171:108344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2022.108344.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2022.

Domsalla M, Koppe G, Niedtfeld I, Vollstädt-Klein S, Schmahl C, Bohus M, et al. Cerebral processing of social rejection in patients with borderline personality disorder. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9:1789–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nst176.

Kleindienst N, Hauschild S, Liebke L, Thome J, Bertsch K, Hensel S, et al. A negative bias in decoding positive social cues characterizes emotion processing in patients with symptom-remitted Borderline Personality Disorder. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-019-0114-3.

Weinbrecht A, Niedeggen M, Roepke S, Renneberg B. Feeling excluded no matter what? Bias in the processing of social participation in borderline personality disorder. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;19:343–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2018.04.031.

Renneberg B, Herm K, Hahn A, Staebler K, Lammers CH, Roepke S. Perception of social participation in borderline personality disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2012;19:473–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.772.

Sadikaj G, Russell JJ, Moskowitz DS, Paris J. Affect dysregulation in individuals with borderline personality disorder: persistence and interpersonal triggers. J Pers Assess. 2010;92:490–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.513287.

Bhatia V, Davila J, Eubanks-Carter C, Burckell LA. Appraisals of daily romantic relationship experiences in individuals with borderline personality disorder features. J Family Psychol. 2013;27:518–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032870.

Reichenberger J, Eibl JJ, Pfaltz M, Wilhelm FH, Voderholzer U, Hillert A, et al. Don’t praise me, don’t chase me: Emotional reactivity to positive and negative social-evaluative videos in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2017;31:75–89. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2016_30_238.

Clark L, Lawrence AJ, Astley-Jones F, Gray N. Gambling near-misses enhance motivation to gamble and recruit win-related brain circuitry. Neuron. 2009;61:481–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.031.

Baer RA, Peters JR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Geiger PJ, Sauer SE. Emotion-related cognitive processes in borderline personality disorder: a review of the empirical literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32:359–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.03.002.

Korn CW, La Rosée L, Heekeren HR, Roepke S. Social feedback processing in borderline personality disorder. Psychol Med. 2016;46:575–87. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171500207X.

Liebke L, Koppe G, Bungert M, Thome J, Hauschild S, Defiebre N, et al. Difficulties with being socially accepted: an experimental study in borderline personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018;127:670–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000373.

Doell KC, Olié E, Courtet P, Corradi-Dell’Acqua C, Perroud N, Schwartz S. Atypical processing of social anticipation and feedback in borderline personality disorder. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;25:102126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102126.

Daniel R, Pollmann S. Comparing the neural basis of monetary reward and cognitive feedback during information-integration category learning. J Neurosci. 2010;30:47–55. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2205-09.2010.

Ullsperger M, Von Cramon DY. Error monitoring using external feedback: Specific roles of the habenular complex, the reward system, and the cingulate motor area revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4308–14. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.23-10-04308.2003.

Knutson B, Fong GW, Bennett SM, Adams CM, Hommer D. A region of mesial prefrontal cortex tracks monetarily rewarding outcomes: Characterization with rapid event-related fMRI. Neuroimage. 2003;18:263–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-8119(02)00057-5.

Vega D, Torrubia R, Soto À, Ribas J, Soler J, Pascual JC, et al. Exploring the relationship between non suicidal self-injury and borderline personality traits in young adults. Psychiatry Res. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.008.

Brown RC, Plener PL, Groen G, Neff D, Bonenberger M, Abler B. Differential neural processing of social exclusion and inclusion in adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury and young adults with borderline personality disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:267. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00267.

Malejko K, Neff D, Brown RC, Plener PL, Bonenberger M, Abler B, et al. Neural signatures of social inclusion in borderline personality disorder versus non-suicidal self-injury. Brain Topogr. 2019;32:753–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-019-00712-0.

Andover MS, Morris BW. Expanding and clarifying the role of emotion regulation in nonsuicidal self-injury. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59:569–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405901102.

Gioia F, Rega V, Boursier V. Problematic internet use and emotional dysregulation among young people: a literature review. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2021;18:41–54. https://doi.org/10.36131/cnfioritieditore20210104.

Koudys JW, Traynor JM, Rodrigo AH, Carcone D, Ruocco AC. The NIMH research domain criteria (RDoC) initiative and its implications for research on personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1023-2.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Grant (ref. PID2021-129109OB-I00) funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033) and by FEDER, UE. D.V.M and J.M.P. are supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (PID2021-129109OB-I00 to D.V.M. and PID2021-126477NB-I00 to J.M.-P.) and the Government of Catalonia (2021 SGR 00352 to J.M-P). SN was supported by a doctoral fellowship from “La Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434; code: LCF/BQ/DR21/11880013). J.M-P was partially supported by ICREA under the ICREA academia program. We thank Laura Dolz for her assistance during the fMRI experiments, and we also thank all participants who made this study possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SN, DV, and JMP conceptualized the study and designed the experiments. SN was responsible for participant recruitment, data acquisition, data analysis, figure preparation, and drafting the initial manuscript. DV, AJ, DO, CS, JS, and JCP assisted with participant recruitment; DV and DO also supported data acquisition. DV and JMP secured funding for the study and provided significant contributions to data interpretation, manuscript review, and editing. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nicolaou, S., Julià, A., Otero, D. et al. Reward-related neural activation during social media exposure in young women with non-suicidal self-injury: evidence for a continuum of severity in the reward network. Transl Psychiatry 15, 308 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03536-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03536-8