Abstract

Observational studies have produced inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) risk. Residual confounding and potential reverse causality are inevitable in such conventional observational studies. We tried to examine the causal relationship between AD and CSVD-related phenotypes using genetic methods. Genetic instruments for each AD and CSVD-related phenotypes (cerebral microbleeds, white matter hyperintensity, and lacunar stroke) were derived from large-scale genome-wide association studies. In this study, two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) tested potential causal associations between AD and CSVD-related phenotypes, followed by a colocalization analysis to corroborate MR findings and explain possible mechanisms. Using univariable MR, we observed that genetic liability to AD was associated with an increased risk of cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) [odds ratio (OR) = 1.149; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.070–1.235, P < 0.001], and a modest increase in white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) volume (β = 0.031 mm3, 95% CI = 0.009–0.054 mm3, P = 0.005). In multivariable MR, the causal effect of genetic liability for AD on CMBs and WMHs remained after adjusting for risk factors, with the estimate across the IVW method. Colocalization results provided evidence for a shared causal variant between AD with CMBs (PPH4 = 0.996) and WMHs (PPH4 = 0.657), suggesting that the MR estimates were not confounded by linkage disequilibrium. Our MR analyses provided robust evidence for the causal effects of genetic liability for AD on an increased risk of CMBs and WMHs. More work is warranted to confirm the mechanisms of association between AD and CSVD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent cause of dementia, accounting for approximately 60% of all cases. The main pathological hallmarks of AD include but are not limited to the amyloid β-protein (Aβ) cascade hypothesis and tau hypothesis. However, the molecular basis of AD remains controversial and effective treatments are still not available [1]. Recently, the connection between cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) and AD has gained much attention due to their common risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes, as well as similar pathophysiological mechanisms, such as mitochondrial disruption, oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, and inflammation [2]. CSVD comprises a variety of disorders affecting small arteries and microvessels of the brain, manifesting as white matter hyperintensities (WMHs), cerebral microbleeds (CMBs), and lacunar stroke. Since the causes of AD were first explored, studies have focused on the relationship between AD and CSVD [3, 4]. Findings from previous epidemiological studies have reported that patients with WMHs may have an increased risk of AD [5, 6]. According to Sparacia et al. [7], AD patients have a higher prevalence of CMBs. CMBs may play a role in the pathophysiological mechanism of AD and contribute to the development of cognitive dysfunction. However, other studies did not replicate this association, which raised doubts about its validity as a correlation [2]. It is widely recognized that traditional observational studies do not provide insights into causality [8]. Therefore, it is still uncertain whether the links between AD and CSVD are causal.

Mendelian randomization (MR), using genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) to assess the causal effects of risk factors related to diseases, can overcome confounding biases inherent in observational studies. Previous studies have found a causal relationship between AD and other diseases by using MR analysis; however, the causal association between AD and CSVD has not yet been demonstrated. Herein, we adopted bidirectional MR analysis to investigate the causal association between AD and CSVD phenotypes. And then, we performed multivariate MR analysis to determine whether the observed association was driven by body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure (SBP), type 2 diabetes (T2D), low density lipoprotein (LDL) and smoking. Finally, the colocalization analysis was performed for the MR findings at P < 0.05 to detect shared genetic architecture, adding supportive mechanisms to the causal relationship.

Methods

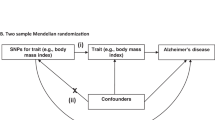

Study design

This study conducted a two-sample MR study to explore the causal relationship between AD and CSVD-related phenotypes (CMBs, WMHs, and lacunar stroke). Our study is based on the MR design, which depends on three core assumptions: first, the genetic variant selected as an instrumental variable is associated with exposure of interest; second, the genetic variants should not be associated with any potential confounders; and third, genetic variants affect the outcome only through the exposure of interest [9].

Data sources

We derived summary-level statistics for clinically diagnosed late-onset AD from Kunkle et al.’s latest GWAS meta-analysis of non-Hispanic Whites (17 new, 46 total datasets; 21,982 cases, 41,944 cognitively normal controls) [10]. The summarized data for genetic variants of lacunar stroke were obtained from a meta-analysis of GWAS (including previous GWAS from Europe, the USA, and Australia and additional cases and controls from the UK DNA Lacunar Stroke Studies and the International Stroke Genetics Consortium), including 225,419 samples (6030 lacunar stroke cases and 248,929 controls) [11]. Meanwhile, we used publicly available summary statistics from published GWAS of CMBs (3556 out of 25,862 participants had CMBs), which performed genome-wide association studies in 11 population-based cohort studies and 3 case‒control or case-only stroke cohorts [12].Summary-level data for WMHs variants were obtained from a GWAS meta-analysis of WMHs in 11,226 individuals, including 8429 population-based individuals from the UK Biobank and 2797 stroke patients [13]. Summary-level statistics for the common risk factors for BMI (GWAS ID: ieu-b-4816, the data of 99,998 individuals), SBP (GWAS ID: ieu-b-4818, the data of 97,656 individuals), T2D (GWAS ID: ebi-a-GCST90018926, including 38,841 cases and 451,248 controls), LDL (GWAS ID: ieu-b-4846, the data of 770,814 individuals), and smoking initiation (GWAS ID: ieu-b-4877, including 311,629 cases and 321,173 controls) were obtained from the GWAS website (http://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets); both sets of data were of European descent.

Selection of genetic Instruments

SNPs that met the genome-wide significance level (P < 5 × 10−8) were initially selected as genetic instruments. If no SNPs met the genome-wide significance level, a lower threshold of P < 1 × 10−5 was used [14]. The corresponding linkage disequilibrium (LD) was identified, we confirmed that the SNP was in a state of LD, and the independence of the SNP was realized by cutting the SNP into a 10,000 kb window (r2 < 0.1) [15]. If SNPs for exposure were unavailable in the outcome data, we then identified proxy SNPs at the threshold of LD r2 > 0.8 on SNiPA (https://snipa.helmholtz-muenchen.de/snipa3/index.php). For those absent in the outcome data with no appropriate proxies available, we excluded them.

Statistical analysis

A bidirectional MR analysis was performed to determine the causal relationship between AD and CSVD-related phenotypes. We used the random-effects inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method as the primary analysis, which combines the Wald ratio estimates to obtain a consistent estimate of the causal effect of the exposure on the outcome [16]. Moreover, F statistics were calculated to assess the strength of the selected genetic instruments in MR analysis. F statistics greater than 10 are generally considered strong [17]. Additionally, other methods including MR-Egger regression, weighted median, simple mode, weighted mode, and the Mendelian randomization pleiotropy residual sum and outlier (MR-PRESSO) tests were used as sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of MR effect estimates to potential invalid genetic variants [16, 18, 19]. Moreover, MR‒Egger and MR-PRESSO analyses were conducted to evaluate the pleiotropy effects. An intercept distinct from the origin indicates the presence of pleiotropic effects (P for MR‒Egger <0.05) [20]. In addition, the leave-one-out (LOO) analysis was used to assess whether the causal effect was driven by an influential SNP via recalculating the MR estimates by leaving one instrument out at a time [21]. If estimates of these approaches in our study were inconsistent, a tightened instrument p value threshold was set, and then the MR analysis was performed again [22]. A reverse MR analysis was performed using each CSVD phenotype as an exposure and AD as an outcome to explore reverse causation between CSVD phenotypes and AD. The selection of the genetic instruments and other analytic methods for this reverse MR analysis were identical to those of the primary analysis described earlier.

To investigate whether the degree of bias introduced by sample overlap impacted observed casual associations, we performed a sensitivity analysis using MRlap software, which is robust to bias introduced by sample overlap, winner’s curse and weak instruments [23]. According to the results of the search on the PhenoScanner website and possible confounding factors between exposures and outcomes, we performed the multivariate MR analysis to determine whether observed associations were driven by BMI, SBP, T2D, LDL and smoking. The IVW method was used in the multivariate MR analysis. Heterogeneity of IVW method was evaluated based on the Q-statistic, and pleiotropy was also appraised according to the intercept term derived from Egger regression [16].

To further validate the robustness and generalizability of the initially observed causal relationship between AD and CSVD-related phenotypes, we conducted a replication MR analysis. For this purpose, we used an independent AD GWAS summary dataset from the FinnGen consortium (finn-b-G6_ALZHEIMER). This dataset is derived from a Finnish population-based cohort and offers extensive summary statistics on genetic associations with AD risk, encompassing 3899 cases and 214,893 controls. The selection of genetic instruments and the analytical methods employed in the replication analysis were consistent with those utilized in the primary analysis.

Finally, we performed colocalization analysis between the exposure and the outcome pairs (for the MR findings at P < 0.05) given a 500 kb window (±250 kb) around each locus using COLOC package (https://github.com/chr1swallace/coloc, V.5.2.0) [24]. We assume that at most one causal variant for a trait lies within the locus, and under this assumption, the method enumerates across all the possibilities to test the competing hypotheses of H0: no causal variants; H1: causal variant for exposure only; H2: causal variant for outcome only; H3: distinct causal variants for exposure and outcome; and H4: shared causal variant for exposure and outcome. A high posterior probability (PP) for H4 (PPH4) would suggest colocalization which supports the MR results, while a high PP for H3 (PPH3) would suggest that the observed MR results may be due to LD between separate causal variants for the traits. We used the default priors of 10−4, 10−4 and 10−5 for a variant being associated with exposure, outcome, and both traits, respectively [25]. PPH4 > 0.5 was used as the threshold for evidence of colocalization, signifying that colocalization is more likely than any other scenario combined [26].

Statistical analyses and data visualization were performed using R software, version 4.2.0 (http://www.r-project.org), with the TwoSampleMR, MR-PRESSO, and MRlap packages [23, 27].

Results

Univariable MR analysis

After data harmonization, 31, 50, and 40 independent SNPs were selected as IVs to analyse the association between AD with CMBs, WMHs, and lacunar stroke, respectively (Supplementary Table 1–3). According to the IVW method, the risk of CMBs is significantly higher in individuals with genetically predicted AD [odds ratio (OR) = 1.149; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.070–1.235; P < 0.001] (Fig. 1). Additionally, genetically predicted AD was found to be significantly associated with a modest increase of 0.031 mm3 in WMHs (β = 0.031, 95% CI = 0.009–0.054, P = 0.005). No obvious causal effect of genetically determined AD on lacunar stroke (OR 1.008, 95% CI: 0.969–1.049, P = 0.699) (Fig. 1). Besides, Cochran’s Q-test suggested that there was only little heterogeneity regarding the associations between AD and CSVD phenotypes. And the MR-Egger intercepts were not statistically significant (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, and Supplementary Table 4). Furthermore, leave-one-out analysis confirmed that the pooled IVW estimate was not reliant upon any single SNP (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

The slope of each line corresponds to the estimated MR effect from different methods. Each dot represents an instrumental single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). The x-axis represents the genetic association with the exposure; the y-axis represents the genetic association with risk of the outcome. The slope of each line represents the causal estimate of an exposure on the corresponding outcome per method. AD Alzheimer’s disease, CMBs cerebral microbleeds, WMHs white matter hyperintensities.

Black boxes corresponding to each of the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) denote odds ratios (OR) derived from inverse variance weighted (IVW) after leaving the corresponding SNP in turns. The black box corresponding to “All” indicates the pooled IVW MR estimate. Horizontal lines denote a 95% confidence interval (CI).

In the reverse MR analyses, we used a lenient threshold of P < 1 × 10−5 for these analyses due to not enough of the SNPs reached the criteria for genome-wide association significance (P value). And 15 SNPs were selected as the genetic instruments for CMBs, 23 SNPs for WMHs, and 41 for lacunar stroke (Supplementary Table 5–7). The primary analysis revealed no significant association of genetic liability to CMBs, WMHs, and lacunar stroke with AD using the IVW method. MR estimates were similar among different MR methods. Sensitivity analysis indicated that no heterogeneity or pleiotropy was detected (Supplementary Table 8, and Supplementary Figs. 3–5).

These results suggest a potential unidirectional causal relationship, wherein genetically predicted AD elevates the risk of CMBs and WMHs, but not lacunar stroke, thereby indicating a selective vascular impact attributable to AD-related pathophysiology.

Assessing the impact of sample overlap

The analysis results of “MRlap” showed that after adjusting for the impact of sample overlap, the causal effects between genetically predicted AD with CMBs and WMHs were consistent to the results of two-sample MR. This result indicated that potential sample overlap between the exposure and outcome datasets did not substantially bias our MR estimates, supporting the reliability of the primary findings (Supplementary Table 9).

Multivariate MR analysis

In multivariate MR analysis, the causal effect of genetic liability for AD on CMBs and WMHs remained after adjusting for BMI (CMBs: IVW OR = 1.143, 95% CI = 1.060–1.233, P < 0.001; WMHs: IVW OR = 1.039, 95% CI = 1.016–1.063, P < 0.001), SBP(CMBs: IVW OR = 1.150, 95% CI = 1.065–1.243, P < 0.001; WMHs: IVW OR = 1.037, 95% CI = 1.015–1.059, P < 0.001), T2D(CMBs: IVW OR = 1.141, 95% CI = 1.069–1.218, P < 0.001; WMHs: IVW OR = 1.031, 95% CI = 1.009–1.053, P = 0.006), LDL(CMBs: IVW OR = 1.138, 95% CI = 1.055–1.226, P < 0.001; WMHs: IVW OR = 1.038, 95% CI = 1.013–1.063, P = 0.003), and smoking (CMBs: IVW OR = 1.157, 95% CI = 1.080–1.240, P < 0.001; WMHs: IVW OR = 1.038, 95% CI = 1.016–1.060, P < 0.001). The results of Cochran’s Q test indicated no significant heterogeneity, and there was no evidence of horizontal pleiotropy based on the Egger intercepts (Fig. 4).

Het. P refers to P-values for heterogeneity of inverse variance weighted method. Ple. P refers to P-values for pleiotropy of inverse variance weighted method. SNP single nucleotide polymorphism, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, BMI body mass index, SBP systolic blood pressure, T2D type 2 diabetes, LDL low density lipoprotein.

The consistent associations between AD and both CMBs and WMHs, even after adjustment for common vascular and metabolic risk factors, implied that AD might have contributed to CSVD phenotypes through independent biological mechanisms.

Replication MR analysis

To enhance the robustness of the previously identified significant associations, we conducted a replication MR analysis using additional GWAS summary statistics on AD from the FinnGen consortium, which did not overlap with the individuals included in the initial analysis. The results from the replication analysis showed that the direction of the causal associations between AD and both CMBs (OR = 1.082, 95% CI = 1.015–1.152, P = 0.015) and WMHs (β = 0.026, 95% CI = 0.009–0.043, P = 0.003) were consistent with those observed in the primary analysis, further supporting the robustness and stability of our findings (Supplementary Table 10).

Colocalization analysis

We conducted colocalization analyses of AD with CMBs and WMHs. Colocalization results provided evidence for a shared causal variant between AD with CMBs (PPH4 = 0.996) and WMHs (PPH4 = 0.657), implicating that AD in the increase of CMBs and WMHs risk (Supplementary Figs. 6, 7).

Discussion

The aim of this study was aimed to investigate the causal relationship between AD and CSVD. In the present MR study, we find strong MR and colocalization evidence for the causal effects of genetic liability for AD on an increased risk of CMBs and WMHs. In the reverse MR analyses, no evidence shown significant association of genetic liability to CMBs, WMHs, and lacunar stroke with AD.

AD is a multifactorial neurodegenerative disease that stems from multiple factors and is clinically identified by a gradual decline in memory and other cognitive functions [28]. In addition to neuropathology (i.e., β-amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles), CSVD has been recognized as a crucial pathogenesis in AD [29]. Data from epidemiological and clinical-pathological studies have supported a relationship between CSVD and AD. Findings from previous epidemiological studies have reported that patients with WMHs may have an increased risk of AD [5, 6]. Studies found that CMBs were considered indicative of small-vessel blood leakage, and they have been more frequently observed in patients with AD than in the general elderly population [30, 31]. The incidence of CMBs in the elderly population without dementia or any other health issues was 16.8%, and in the dementia population, it was 22%, while it was as high as 24% in AD patients. As of yet, the causal relationship between AD and CSVD has remained unclear. Moreover, previous observational studies faced challenges in avoiding confounding risk factors, whereas the current study, utilizing MR methods, allows for a more robust study design and enables us to establish causality with confidence and without bias [9]. The primary MR analyses in our study were performed using the IVW method, which provides the most precise estimates. Additionally, we employed complementary MR methods to rigorously assess potential violations of MR assumptions.

Although we have found that AD increases the occurrence of CMBs and WMHs, the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the relationship between AD and CMBs are still poorly understood and highly debated. AD is characterized by the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques and tau protein tangles in the brain, which lead to the death of neurons and the progressive deterioration of cognitive function. Several studies have indicated that the occurrence of CSVD in AD patients may be related to amyloidosis. AD is characterized by the accumulation of Aβ and tau protein tangles in the brain, which can lead to neuronal death and a progressive decline in cognitive function. The accumulation of Aβ in the brain may weaken the walls of blood vessels, making them more vulnerable to rupture and ultimately leading to the development of CMBs. Poliakova et al. [32] conducted a comprehensive analysis of early-stage AD patients and found that those with CMBs had lower levels of Aβ in their cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), particularly Aβ42 levels. Another study also indicated that AD patients with CMBs have lower levels of Aβ in the CSF, and there is a significant negative correlation between the number of CMBs and the level of Aβ in the CSF [7]. Moreover, according to a study utilizing Aβ PET imaging and data from the ADNI database, WMHs have a stronger correlation with cerebral Aβ build-up than any of the typical imaging biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease [33]. A recent study conducted in the United States by the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center’s Data Sets with 82 participants discovered a clear link between the total volume of WMHs and an elevated risk of displaying AD neuropathology [34]. Furthermore, Yi HA et al. also found that the high-WMH group exhibited a greater cerebral Aβ burden than the low-WMH group and that the cerebral Aβ burden was positively correlated with WMH burden [35]. It is possible that the connection between CSVD and AD is linked to cerebral amyloid angiopathy. However, more studies are necessary to comprehend the root causes completely.

In addition, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is associated with the formation of CMBs in patients with AD [36]. VEGF is an effective glycoprotein that promotes angiogenesis and plays an important role in controlling vascular permeability. Zhang et al. [36] compared the serum levels of VEGF in AD patients with and without CMBs and found that AD patients with CMBs had higher levels of serum VEGF, which was positively correlated with the number of CMBs. This indicates that the formation of CMBs in AD patients is associated with an increase in VEGF levels. Additionally, Hatada et al. [37] recorded the number of CMBs through MRI and compared the differences in cerebral blood flow between AD patients using perfusion imaging. The results showed that AD patients with multiple CMBs had reduced cerebral blood flow, suggesting that CMBs in AD patients may also be related to cerebral hypoperfusion. As early as 1997, research has shown that the upregulation of VEGF is a physiological response to tissue hypoxia, and the severity of white matter hypoperfusion associated with small vascular disease in AD patients is closely related to VEGF levels [38]. Therefore, CMBs may also be associated with cerebral hypoperfusion through VEGF.

Our MR analyses provided genetic evidence that AD was significantly associated with CMBs and WMHs. There are some strengths in our study. First, data were obtained from different samples, and genetic associations can be gained from large GWAS, which considerably improves the statistical power for the detection of small effects in complex phenotypes [39]. Second, the genetic variants were distributed on separate chromosomes, and underlying gene‒gene interactions might have little influence on the effects [40]. Finally, the multivariate MR analysis is a major strength in this work. With adjustment for common risk factors, the multivariate MR allowed us to obtain a direct effect of genetic liability for AD on CSVD. There are, however, several limitations to our study. First, the enrolled patients were all European; hence, there is no evidence that AD and CSVD are causally linked in other populations. Second, despite the corroborating colocalization and sensitivity analyse found that there is unlikely any genetic confounding through a variant in LD can be attributed to the MR findings [25], there remains the possibility that the MR estimates may be biased by the pleiotropic effects of the genetic variants employed as instruments. However, as demonstrated by Cronjé et al. [26], this possibility can never be entirely excluded. Third, in the reverse MR analysis, due to the limited availability of genome-wide significant variants for CSVD-related phenotypes, we adopted a relatively lenient SNP selection threshold (P < 1 × 10−5). While this approach may introduce weak instrument bias and diminish statistical power, the F-statistics for the selected instruments demonstrated sufficient strength, thereby alleviating concerns regarding instrument weakness. Nonetheless, the absence of significant causal associations in the reverse MR analyses should be interpreted with caution, and future studies incorporating stronger genetic instruments are warranted.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our MR analyses provided robust evidence for the causal effects of genetic liability for AD on an increased risk of CMBs and WMHs. More work is warranted to confirm the mechanisms of association between AD and CSVD.

Data availability

All the data used in this study can be acquired from the original genome-wide association studies that are mentioned in the text. Any other data generated in the analysis process can be requested from the corresponding author.

References

Ryan NS, Rossor MN, Fox NC. Alzheimer’s disease in the 100 years since Alzheimer’s death. Brain. 2015;138:3816–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv316

Liu Y, Braidy N, Poljak A, Chan DKY, Sachdev P. Cerebral small vessel disease and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2018;47:41–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2018.06.002

Kim HW, Hong J, Jeon JC. Cerebral small vessel disease and Alzheimer’s disease: a review. Front Neurol. 2020;11:927 https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00927

Moghekar A, Kraut M, Elkins W, Troncoso J, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM, et al. Cerebral white matter disease is associated with Alzheimer pathology in a prospective cohort. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:S71–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2012.04.006

Kim S, Choi SH, Lee YM, Kim MJ, Kim YD, Kim JY, et al. Periventricular white matter hyperintensities and the risk of dementia: a CREDOS study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:2069–77. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610215001076

Hertze J, Palmqvist S, Minthon L, Hansson O. Tau pathology and parietal white matter lesions have independent but synergistic effects on early development of Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2013;3:113–22. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348353

Sparacia G, Agnello F, La Tona G, Iaia A, Midiri F, Sparacia B. Assessment of cerebral microbleeds by susceptibility-weighted imaging in Alzheimer’s disease patients: a neuroimaging biomarker of the disease. Neuroradiol J. 2017;30:330–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1971400916689483

Jiang L, Li JC, Tang BS, Guo JF, Shen L. Lack of bidirectional association between age-related macular degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18:2725–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12775

Liu R, Shi X, Feng J, Piao J, Yang Z, Zhao Y et al. Ischemic stroke and cerebral microbleeds: a two-sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Neurol Ther. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00500-w.

Kunkle BW, Grenier-Boley B, Sims R, Bis JC, Damotte V, Naj AC, et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet. 2019;51:414–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0358-2

Traylor M, Persyn E, Tomppo L, Klasson S, Abedi V, Bakker MK, et al. Genetic basis of lacunar stroke: a pooled analysis of individual patient data and genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20:351–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(21)00031-4

Knol MJ, Lu DW, Traylor M, Adams HHH, Romero JRJ, Smith AV, et al. Association of common genetic variants with brain microbleeds A genome-wide association study. Neurology. 2020;95:E3331–E43. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000010852

Traylor M, Tozer DJ, Croall ID, Lisiecka-Ford DM, Olorunda AO, Boncoraglio G, et al. Genetic variation in PLEKHG1 is associated with white matter hyperintensities (n = 11,226). Neurology. 2019;92:e749–e57. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000006952

Lee KJ, Kim H, Lee SJ, Duperron MG, Debette S, Bae HJ, et al. Causal effect of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration on cerebral small vessel disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Stroke. 2023;54:2338–46. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.123.042980

Nazarzadeh M, Pinho-Gomes AC, Smith Byrne K, Canoy D, Raimondi F, Ayala Solares JR, et al. Systolic blood pressure and risk of valvular heart disease: a mendelian randomization study. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:788–95. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2019.2202

Cai J, He L, Wang H, Rong X, Chen M, Shen Q, et al. Genetic liability for prescription opioid use and risk of cardiovascular diseases: a multivariable Mendelian randomization study. Addiction. 2022;117:1382–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15767

Burgess S, Thompson SG. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:755–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyr036

Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50:693–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:304–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.21965

Tian D, Zhang L, Zhuang Z, Huang T, Fan D. A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis of heart rate variability and cerebral small vessel disease. J Clin Hypertens. 2021;23:1608–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.14316

Burgess S, Bowden J, Fall T, Ingelsson E, Thompson SG. Sensitivity analyses for robust causal inference from Mendelian randomization analyses with multiple genetic variants. Epidemiology. 2017;28:30–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0000000000000559

Chen X, Kong JQ, Pan JX, Huang K, Zhou WH, Diao XY, et al. Kidney damage causally affects the brain cortical structure: a Mendelian randomization study. EBioMedicine. 2021;72:103592 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103592

Mounier N, Kutalik Z. Bias correction for inverse variance weighting Mendelian randomization. Genet Epidemiol. 2023;47:314–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.22522

Giambartolomei C, Vukcevic D, Schadt EE, Franke L, Hingorani AD, Wallace C, et al. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004383 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004383

Zuber V, Grinberg NF, Gill D, Manipur I, Slob EAW, Patel A, et al. Combining evidence from Mendelian randomization and colocalization: review and comparison of approaches. Am J Hum Genet. 2022;109:767–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.04.001

Cronjé HT, Karhunen V, Hovingh GK, Coppieters K, Lagerstedt JO, Nyberg M, et al. Genetic evidence implicating natriuretic peptide receptor-3 in cardiovascular disease risk: a Mendelian randomization study. BMC Med. 2023;21:158 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02867-x

Liu J, Xu H, Cupples LA, O’ Connor GT, Liu CT. The impact of obesity on lung function measurements and respiratory disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Ann Hum Genet. 2023;87:174–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/ahg.12506

Li K, Fu Z, Luo X, Zeng Q, Huang P, Zhang M, et al. The influence of cerebral small vessel disease on static and dynamic functional network connectivity in subjects along Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Brain Connect. 2021;11:189–200. https://doi.org/10.1089/brain.2020.0819

Azarpazhooh MR, Avan A, Cipriano LE, Munoz DG, Sposato LA, Hachinski V. Concomitant vascular and neurodegenerative pathologies double the risk of dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:148–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2017.07.755

Benedictus MR, Prins ND, Goos JD, Scheltens P, Barkhof F, van der Flier WM. Microbleeds, mortality, and stroke in Alzheimer disease: the MISTRAL study. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:539–45. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.14

Greenberg SM, Vernooij MW, Cordonnier C, Viswanathan A, Al-Shahi Salman R, Warach S, et al. Cerebral microbleeds: a guide to detection and interpretation. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:165–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(09)70013-4

Poliakova T, Levin O, Arablinskiy A, Vasenina E, Zerr I. Cerebral microbleeds in early Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol. 2016;263:1961–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-016-8220-2

Kandel BM, Avants BB, Gee JC, McMillan CT, Erus G, Doshi J, et al. White matter hyperintensities are more highly associated with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease than imaging and cognitive markers of neurodegeneration. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;4:18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2016.03.001

Alosco ML, Sugarman MA, Besser LM, Tripodis Y, Martin B, Palmisano JN, et al. A clinicopathological investigation of white matter hyperintensities and Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63:1347–60. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-180017

Yi HA, Won KS, Chang HW, Kim HW. Association between white matter lesions and cerebral Aβ burden. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0204313 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204313

Zhang JB, Li MF, Zhang HX, Li ZG, Sun HR, Zhang JS, et al. Association of serum vascular endothelial growth factor levels and cerebral microbleeds in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23:1337–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.13030

Hatada Y, Hashimoto M, Shiraishi S, Ishikawa T, Fukuhara R, Yuki S, et al. Cerebral microbleeds are associated with cerebral hypoperfusion in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75:351 https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-209002

Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer disease meta analysis consortium. JAMA. 1997;278:1349–56. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.278.16.1349

Lawlor DA. Commentary: two-sample Mendelian randomization: opportunities and challenges. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:908–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw127

Wang T, Xu L. Circulating vitamin E levels and risk of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction: a Mendelian randomization study. Nutrients. 2019;11:2153 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092153

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the original GWASs and the related consortiums for sharing and managing the summary statistics.

Funding

This study was supported by the Tianhua Health Public Welfare Foundation of Jilin Province (Grant number: J2024JKJ026), the Jilin Provincial Medical and Health Talents Project (JLSRCZX2025-29) and the Research and Innovation Capacity Enhancement Program for Doctoral Students, Jilin University (2024KC141).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Renjie Liu proposed the idea and wrote the draft of the manuscript. Lanlan Chen and Renjie Liu contributed to the data analysis and manuscript revision. Lanlan Chen prepared the figures and tables. Xuan Chen supervised the whole research and is responsible for the integrity of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This study used publicly available deidentified data from participant studies that were approved by an ethical standards committee with respect to human experimentation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, R., Chen, L. & Chen, X. Causal relationship between Alzheimer’s disease and cerebral small vessel disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Transl Psychiatry 15, 317 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03560-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03560-8

This article is cited by

-

Cerebral microbleeds aggravate severity of motor function, cognitive and emotional status in Parkinson’s disease

Acta Neurologica Belgica (2025)