Abstract

Dysconnectivity in the corticostriatal pathway, which is central to psychosis pathophysiology, is also known to be present in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis (CHR-P). Considering that the corticostriatal pathway actively matures until adulthood and that neuroanatomical maturation is suggested to be related to functional outcomes in individuals at CHR-P, longitudinal studies on the corticostriatal structural pathway in individuals at CHR-P are warranted. To characterize the longitudinal trajectory of corticostriatal structural connectivity, diffusion-weighted images were collected from 23 individuals at CHR-P and 20 healthy controls (HCs) at baseline and at a 2-year follow-up visit. Probabilistic tractography was performed to segment the pathways between seven cortical regions and the striatum. The relative connectivity between each cortical region and associated striatal subregion was calculated. The CHR-P group was divided into subgroups according to the functional outcome of the modified Global Assessment of Functioning score at follow-up. A significant group‒time interaction between the left orbitofrontal cortex and its associated striatal subregion was found, with a negative slope in the CHR-P group and positive slope in the HC group. In the left orbitofrontal corticostriatal relative connectivity, the group‒time interaction between HCs and individuals at CHR-P with poor functional outcomes at follow-up was statistically significant, whereas that between HCs and individuals at CHR-P with good functional outcomes at follow-up was not. These findings indicate abnormal white matter maturation of the orbitofrontal corticostriatal pathway in individuals at CHR-P. Abnormal neuroanatomical maturation of the orbitofrontal corticostriatal pathway may reflect prognosis for functional outcomes in these individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The concept of clinical high risk for psychosis (CHR-P) represents a prospective framework for identifying individuals in the putative prodromal stage of psychosis [1]. This framework has provided a basis for investigating the neurobiological changes that precede the onset of psychosis and for developing potential early intervention strategies to prevent the transition to psychosis [2]. Nevertheless, recent findings have shown that the population at CHR-P is heterogeneous not only in terms of clinical and functional outcomes [3, 4] but also in terms of the neurobiological characteristics measured by neuroimaging [5]. Identifying correlates among neurobiological characteristics and outcomes is crucial in the population at CHR-P, as it can lead to the discovery of biomarkers or predictors for the prognosis of individuals at CHR-P [6,7,8].

It has been suggested that the corticostriatal pathway plays a crucial role in the pathophysiology of psychosis [9,10,11]. As an aberrant dopaminergic system has long been regarded as a hallmark of psychosis [9, 12], dysfunctional corticostriatal circuitry has gained attention as a driving mechanism for dysfunctional dopaminergic signaling [13], since the corticostriatal pathway is known to modulate the dopaminergic system [14]. This concept is supported by neuroimaging studies that showed abnormalities in both structural and functional corticostriatal connectivity in psychosis patients [10, 15,16,17]. As the corticostriatal pathway is heavily implicated in the pathophysiology of psychosis, some studies have demonstrated that dysconnectivity in the corticostriatal pathway is also observed in individuals at CHR-P. A resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study reported functional dysconnectivity of the ventral and dorsal corticostriatal circuitry in individuals at CHR-P [18], whereas a diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) study revealed structural alterations in the ventral corticostriatal pathway [19]. These cross-sectional studies imply that, under the context of the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of the psychosis continuum [20, 21], the corticostriatal pathway may undergo abnormal development at some point within critical neurodevelopmental periods in individuals at CHR-P.

Elucidating the presence of an abnormal neurodevelopmental trajectory in individuals at CHR-P is important for exploring the neurobiology of the prognostic heterogeneity of the population at CHR-P, as previous studies have suggested an association between neuroanatomical maturation and the functional outcomes of individuals at CHR-P [22, 23]. From this perspective, the corticostriatal pathway especially warrants further investigation, as it physiologically continues to actively develop until adolescence and adulthood [24], particularly in terms of white matter maturation [25]. Considering the dynamic nature of the structure of the corticostriatal pathway in healthy controls (HCs), a direct longitudinal comparison between individuals at CHR-P and HCs is crucial to characterize how the white matter maturation of the corticostriatal pathway in the population at CHR-P deviates from the typical developmental trajectory and how the deviation is associated with the functional outcomes of individuals at CHR-P.

Our study aimed to longitudinally investigate the white matter connections of the corticostriatal pathway in individuals at CHR-P. More specifically, as different parts of the corticostriatal pathway normally undergo distinct patterns of maturation [26], we examined how the relative connectivity among each part of the corticostriatal pathway differs in individuals at CHR-P across time by parcellating the striatum according to its relative connectivity with the cortical region of interest (ROI). We hypothesized that, compared with HCs, individuals at CHR-P would exhibit different patterns of change in the relative connectivity within the corticostriatal pathway. Furthermore, we explored whether individuals at CHR-P with good or poor functional outcomes presented different longitudinal trajectories of white matter connectivity in the corticostriatal pathway.

Materials and methods

Study participants and clinical assessment

Twenty-three participants at CHR-P and 20 HC participants were included in the study. Participants in the group at CHR-P were enrolled from the Seoul Youth Clinic at Seoul National University Hospital (www.youthclinic.org). Clinical interviews were conducted with participants at CHR-P via the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and the validated Korean version of the Structured Interview of Prodromal Symptoms [27]. Participants who met at least one of the following three established criteria for a prodromal psychosis state were included in the group at CHR-P: the presence of an attenuated positive symptom state (APS), the presence of brief intermittent psychotic symptoms below the threshold required for a DSM-IV Axis I psychotic disorder diagnosis (BIPS), or a 30% decline in global functioning over the past year as well as a diagnosis of schizotypal personality disorder or a history of psychosis in a first-degree relative (genetic risk with deterioration; GRD). At baseline and follow-up, the modified Global Assessment of Functioning (mGAF) was administered to the participants to determine their functional outcomes. Participants at CHR-P who met the criterion of a lifetime diagnosis of a psychotic disorder were excluded.

HC participants were recruited through Internet advertisements. An interview using the SCID-I Nonpatient Edition (SCID-NP) was conducted to screen for psychiatric conditions. Participants with any current or past psychiatric illness or any family history of psychotic disorders were excluded.

Common exclusion criteria for participants at CHR-P and HC participants included the following: lifetime diagnosis of a substance use disorder (except nicotine use disorder), neurological disease or significant head injury, medical illness that may involve psychiatric symptoms, or intellectual disability (intelligent quotient [IQ] < 70).

All participants received thorough explanations of the study and provided written informed consent (IRB no. H-1110-009-380). For participants younger than 18 years, informed consent was also obtained from their parents. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB no. H-2408-158-1565).

Image data acquisition

T1-weighted and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) data were acquired using a 3 T Siemens MAGNETOM Trio Tim Syngo MR B17 scanner. The acquisition parameters for the T1 images were as follows: TR: 1670 ms; TE: 1.89 ms; voxel size: 1 × 0.98 × 0.98 mm; FOV: 250 mm; flip angle: 9°; and slice number: 208 slices. DWI data were acquired via echo‒planar imaging in the axial plane with a TR of 11400 ms, a TE of 88 ms, a 128 × 128 matrix, an FOV of 240 mm and a voxel size of 1.9 × 1.9 × 3.5 mm. Diffusion-sensitizing gradient echo encoding was applied in 64 directions using a diffusion-weighting factor b of 1000 s/mm2. One volume was obtained with a b factor of 0 s/mm2.

Definition of the cortical ROIs

Seven parts of the corticostriatal connections were defined in accordance with the Oxford-GSK-Imanova Striatal Connectivity Atlas [28]. The seven cortical regions of interest (ROIs) were named the caudal-motor, executive, orbitofrontal, rostral-motor, parietal, temporal, and occipital ROIs (Supplementary Figure 1).

Image data processing

T1 images were preprocessed to extract brain tissue images via the automated FreeSurfer pipeline. Individual brain-extracted T1 images were then registered to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standard space (2 × 2 × 2 mm3). Registration was performed using FLIRT with a mutual information cost function, followed by nonlinear registration with FNIRT.

For DWI data, brain tissue extraction and eddy current correction were conducted with FSL. B0 images were used as references to register the participants’ T1 brain images to the diffusion-weighted space. Affine matrices were created via FLIRT with a mutual information cost function to transform T1 images to diffusion space. These matrices were subsequently combined with the transformations obtained from the nonlinear registration of T1 images to the MNI space.

Probabilistic tractography was performed on the individual DWI space to quantify the probability of connection between every voxel in the striatum and each cortical ROI. An FSL probtrackx2 GPU14 was utilized with the following options: number of samples = 5000; number of steps per sample = 2000; step length = 0.5 mm; and curvature threshold = 0.2.

Connectivity calculation

Tract maps obtained through probabilistic tractography had a common threshold at the 50th percentile. This threshold value was set in accordance with the Oxford-GSK-Imanova Striatal Connectivity Atlas [28], where the connection probability threshold was set at the 50th percentile. For each cortical ROI, corticostriatal relative connectivity was calculated as the ratio between the thresholded total number of connections with the cortical ROI and the sum of the thresholded total number of connections across all seven ROIs [29, 30].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted via R version 4.4.1. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05, and multiple comparisons correction was applied using false discovery rate (FDR) correction.

Demographic and clinical variables at baseline were compared via analysis of variance (ANOVA), Welch’s t tests, or chi-square tests, as appropriate. Post hoc tests for ANOVA were performed with Tukey tests.

Baseline corticostriatal relative connectivity for each of the seven cortical ROIs of each hemisphere was compared between the group at CHR-P and the HC group via analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with age at baseline and sex as covariates.

To estimate group‒time interactions of the corticostriatal relative connectivity for each cortical ROI of each hemisphere, mixed models for repeated measures were utilized. Age at baseline and sex were included as covariates in each model. FDR correction was applied for 14 repeated tests (two hemispheres with seven cortical ROIs each).

Subgroup analysis

To address the heterogeneity in the outcomes of individuals at CHR-P, we conducted subgroup analysis for functional outcomes at the 2-year follow-up. Participants at CHR-P were divided into those with good outcomes and those with poor outcomes according to their mGAF scores at the 2-year follow-up. Participants with mGAF scores ≥ 61 at follow-up were classified into the good outcome group, whereas those with mGAF scores < 61 were classified into the poor outcome group [31,32,33,34]. One participant with missing follow-up mGAF data was excluded from the subgroup analysis. Mixed models for repeated measures were established for three groups: participants at CHR-P with good functional outcomes, participants at CHR-P with poor functional outcomes, and HCs. The group‒time interaction effects between the poor functional outcome group and the HC group, as well as between the good functional outcome group and the HC group, were compared.

Sensitivity analysis

The robustness of our results after small changes in the connection probability threshold value applied to the tract maps of striatal connections was tested by repeating the same analyses with slightly different threshold values. The same analyses were conducted with connection probability threshold values at the 40th, 45th, 55th and 60th percentiles. The relative connectivity for each ROI was calculated after thresholding for each additional threshold value, and the same mixed model analyses as those in the main analysis were performed.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants

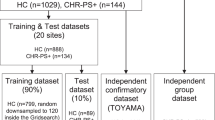

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of each group. Twenty-three participants at CHR-P and 20 HC participants were included in the main analysis. For the subgroup analysis, data from 22 participants at CHR-P and 20 HC subjects were used since one participant at CHR-P had missing follow-up mGAF scale data. Among 22 participants at CHR-P, 13 had a follow-up mGAF score ≥ 61 (i.e., a good functional outcome), and 9 had a follow-up mGAF score < 61 (i.e., a poor functional outcome).

The HCs were significantly older than were the participants at CHR-P (t = 3.68, p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in age between participants at CHR-P with good functional outcomes and participants at CHR-P with poor functional outcomes. At baseline, no significant difference in the mGAF score was observed between participants at CHR-P with good functional outcomes and those with poor functional outcomes.

Baseline corticostriatal relative connectivity

No significant group differences in corticostriatal relative connectivity at baseline were observed for any of the cortical ROIs between participants at CHR-P and HCs after controlling for age at baseline or sex.

Group–time interactions of corticostriatal relative connectivity for each cortical ROI

Among the seven cortical ROIs of each hemisphere, mixed models for repeated measures revealed significant group–time interactions in the relative connectivity of the left orbitofrontal cortical ROI (Fig. 1a and Table 2, FDR-corrected p = 0.029).

a Shows group-time interactions between the group at CHR-P (purple) and the HC group (blue) and (b) indicates those among the group at CHR-P with poor functional outcomes (red), the group at CHR-P with good functional outcomes (orange), and the HC group (blue). For each group at each timepoint, the half violin plots show distributions of the corticostriatal relative connectivity of the left orbitofrontal cortex, and the thick lines connect mean values of the relative connectivity. Abbreviations: CHR-P, individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis; CHR-P good outcomes, individuals at CHR-P with a modified Global Assessment of Functioning score ≥ 61 at follow-up; CHR-P poor outcomes, individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis with a modified Global Assessment of Functioning score < 61 at follow-up; HCs, healthy controls.

Subgroup analysis

Participants at CHR-P with poor functional outcomes and HC participants presented significant group‒time interactions in the left orbitofrontal corticostriatal relative connectivity (Table 3, FDR-corrected p = 0.023), whereas participants at CHR-P with good functional outcomes and HC participants did not (Fig. 1b and Table 3, FDR-corrected p = 0.171).

Sensitivity analysis

Statistically significant group‒time interactions in the relative connectivity of the left orbitofrontal cortical ROI between participants at CHR-P and HCs were observed for all four additional threshold values: the 40th (FDR-corrected p = 0.011), 45th (FDR-corrected p = 0.016), 55th (FDR-corrected p = 0.031) and 60th percentiles (FDR-corrected p = 0.044).

Discussion

In this longitudinal study, we aimed to characterize the differential trajectories of relative connectivity between cortical regions and their associated striatal subregions in individuals at CHR-P by directly comparing baseline and 2-year follow-up longitudinal DWI data from participants at CHR-P and HCs. Furthermore, to account for the heterogeneity of the population at CHR-P in terms of functional outcome, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on mGAF scores at the 2-year follow-up, distinguishing between participants at CHR-P with good functional outcomes and those with poor functional outcomes. Overall, our results demonstrated significant group‒time interactions in relative white matter connectivity between the left orbitofrontal ROI and its associated striatal subregion. Subgroup analysis revealed a statistically significant group‒time interaction in the orbitofrontal corticostriatal relative connectivity between participants at CHR-P with poor functional outcomes and HCs but no significant group‒time interaction between participants at CHR-P with good functional outcomes and HCs. Sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of these findings, indicating that our conclusions were stable after minor changes in the threshold for the connection probability.

The corticostriatal pathway is broadly divided into the dorsal and ventral systems, which are considered both structurally and functionally distinct [35, 36]. Whether the ventral or the dorsal system contributes more to the core pathophysiology of psychosis has been subject to controversy. Although a dysfunctional ventral corticostriatal system has traditionally been hypothesized to be related to psychotic symptoms [37], more recent evidence suggests that the dorsal system is also related to the disease state [15, 17, 38, 39]. Studies targeting high-risk populations have shown that both the ventral and dorsal systems are involved in clinical and genetic high risk [18, 38]. The corticostriatal pathway that showed significant group‒time interactions in our study, namely, the orbitofrontal corticostriatal pathway, constitutes a part of the ventral corticostriatal system. Our results suggest that, during the developmental trajectory of individuals at CHR-P, aberrance in the ventral system is more pronounced to manifest as distinguishable deviations from the normal developmental structural trajectory than aberrance in other parts of the corticostriatal pathway.

Previous cross-sectional studies have suggested that corticostriatal connectivity with the orbitofrontal cortex may play an important role in white matter alterations in the CHR-P population. A previous cross-sectional study on white matter integrity within the corticostriatal pathways revealed reduced white matter integrity, estimated by fractional anisotropy (FA) values, in the limbic corticostriatal pathway in individuals at CHR-P [19]. Furthermore, although they were not tractography studies devoted to corticostriatal pathways, some previous studies that explored the white matter structure in individuals at CHR-P demonstrated that tracts that anatomically correspond to the orbitofrontal corticostriatal pathways, such as segments of the external capsule and the uncinate fasciculus [19], present altered structural characteristics [40,41,42]. These studies, along with our study, point toward the importance of the orbitofrontal corticostriatal pathway in white matter alterations in the population at CHR-P. Nevertheless, our data did not demonstrate significant cross-sectional group differences in corticostriatal relative connectivity. This may be attributed to the dynamic nature of corticostriatal connectivity, which undergoes continuous maturation during the critical neurodevelopmental window that extends to late adolescence and early adulthood [24]. The observed group‒time interaction effect suggests that alterations in corticostriatal connectivity change over time, potentially reflecting an ongoing pathological neurodevelopmental process in individuals at CHR-P.

Our subgroup analysis addressed the heterogeneity of the functional outcomes of the population at CHR-P. Although the concept of CHR-P has been proposed to identify a putative prodromal stage, it has long been known that individuals at CHR-P show diverse prognostic trajectories, which are unconfined to the transition to psychosis [3, 4]. Accordingly, efforts have been made to identify prognostic markers or predictors for the clinical and functional outcomes of individuals at CHR-P, using diverse variables ranging from demographic variables to neuroimaging data [6,7,8]. The results of our subgroup analysis, which revealed differential neurodevelopmental trajectories of orbitofrontal corticostriatal relative connectivity according to functional outcomes in participants at CHR-P, reflect the neuroanatomical heterogeneity of this population [5] and imply that neurodevelopment of the orbitofrontal corticostriatal pathway may constitute a neurobiological indicator of prognosis in these individuals. Furthermore, numerous studies examining specific neurocognitive functions as correlates of functional outcomes in individuals at CHR-P have reported that neurocognitive functions underpinned by the orbitofrontal corticostriatal pathway, such as emotion regulation or reward processing, are associated with functioning in the population at CHR-P [43,44,45,46]. Our results potentially provide a possible neurobiological explanation for the link between these neurocognitive functions and functional outcomes in individuals at CHR-P.

Putatively, neuroanatomical maturation and functional outcome have a reciprocal relationship, since how an individual’s brain functions determines what kind of experiences they are exposed to, which in turn influences the maturation of their brain. Previous studies that investigated the neurodevelopment of the corticostriatal pathway suggest that this pathway is especially relevant to this concept by demonstrating that the corticostriatal pathway normally undergoes active neurodevelopment during the age at which most individuals are at CHR-P [47, 48] and revealing that the neurodevelopment of the corticostriatal pathway is physiologically associated with important behavioral development [47,48,49,50]. The results of our subgroup analysis provide evidence for this potential association by showing that individuals at CHR-P present different developmental trajectories in the structural connectivity of the corticostriatal pathway according to functional outcome (Fig. 2). These results support the findings of previous studies that revealed the relationship between neuroanatomical maturity and outcomes in the population at CHR-P [22, 23] by suggesting that the corticostriatal pathway may be one of the neuroanatomical structures that constitutes the interplay between neuroanatomical maturation and functional outcomes in individuals at CHR-P.

Compared with HC participants, individuals at CHR-P with good functional outcomes (follow-up mGAF scores ≥ 61) presented a preserved trajectory in the corticostriatal relative connectivity of the left orbitofrontal cortex, whereas those with poor functional outcomes (follow-up mGAF scores < 61) presented a significantly aberrant trajectory. Abbreviations: CHR-P, individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis; CHR-P good outcomes, individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis with a modified Global Assessment of Functioning score ≥ 61 at follow-up; CHR-P poor outcomes, individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis with a modified Global Assessment of Functioning score < 61 points at follow-up; mGAF modified Global Assessment of Functioning scale.

This study has several limitations. First, the limited sample size may have resulted in small effect sizes, which would have led to statistically nonsignificant findings. Future studies with larger sample sizes are essential to confirm and extend our results. Second, the 2-year follow-up period may not have been sufficient to fully capture the long-term clinical and neurobiological trajectories of individuals at CHR-P. A longer duration of follow-up and additional follow-up points would better reflect the dynamics of the state of CHR-P. Third, although we addressed the heterogeneity of the population at CHR-P through subgroup analysis, this variability warrants further consideration. The heterogeneity is not limited to the functional outcomes of the population at CHR-P, and future investigations related to other aspects of heterogeneity may be warranted. A study including a larger cohort of individuals at CHR-P would allow for more detailed subgroup analyses, providing a deeper understanding of the diverse outcomes within this population.

This study investigated the 2-year longitudinal course of corticostriatal white matter connectivity in individuals at CHR-P compared with HCs. Our findings revealed that individuals at CHR-P exhibited significantly different longitudinal trajectories in the orbitofrontal corticostriatal pathway, especially in those with poor functional outcomes. These results suggest that the corticostriatal pathway, a critical structure in the pathophysiology of psychosis, is associated with aberrant neurodevelopment in individuals at CHR-P. Furthermore, by revealing its association with functional outcomes, our study suggests that the neurodevelopment of orbitofrontal corticostriatal connectivity may reflect the prognosis of the population at CHR-P.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Fusar-Poli P, McGorry PD, Kane JM. Improving outcomes of first-episode psychosis: an overview. World Psychiatry. 2017;16:251–65.

Fusar-Poli P, de Pablo GS, Correll CU, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Millan MJ, Borgwardt S, et al. Prevention of psychosis: advances in detection, prognosis, and intervention. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:755–65.

de Pablo GS, Besana F, Arienti V, Catalan A, Vaquerizo-Serrano J, Cabras A, et al. Longitudinal outcome of attenuated positive symptoms, negative symptoms, functioning and remission in people at clinical high risk for psychosis: a meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;36:100909.

de Pablo GS, Soardo L, Cabras A, Pereira J, Kaur S, Besana F, et al. Clinical outcomes in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis who do not transition to psychosis: a meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2022;31:e9.

Voineskos AN, Jacobs GR, Ameis SH. Neuroimaging heterogeneity in psychosis: neurobiological underpinnings and opportunities for prognostic and therapeutic innovation. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;88:95–102.

Bossong MG, Antoniades M, Azis M, Samson C, Quinn B, Bonoldi I, et al. Association of hippocampal glutamate levels with adverse outcomes in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:199–207.

Choe E, Ha M, Choi S, Park S, Jang M, Kim M, et al. Beyond verbal fluency in the verbal fluency task: semantic clustering as a predictor of remission in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2023;48:E414–E420.

Kim M, Lee TH, Yoon YB, Lee TY, Kwon JS. Predicting remission in subjects at clinical high risk for psychosis using mismatch negativity. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:575–83.

Howes OD, Bukala BR, Beck K. Schizophrenia: from neurochemistry to circuits, symptoms and treatments. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2024;20:22–35.

Sabaroedin K, Razi A, Chopra S, Tran N, Pozaruk A, Chen Z, et al. Frontostriatothalamic effective connectivity and dopaminergic function in the psychosis continuum. Brain. 2023;146:372–86.

Shepherd GM. Corticostriatal connectivity and its role in disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:278–91.

McCutcheon RA, Abi-Dargham A, Howes OD. Schizophrenia, dopamine and the striatum: from biology to symptoms. Trends Neurosci. 2019;42:205–20.

Sabaroedin K, Tiego J, Fornito A. Circuit-based approaches to understanding corticostriatothalamic dysfunction across the psychosis continuum. Biol Psychiatry. 2023;93:113–24.

Haber SN. The place of dopamine in the cortico-basal ganglia circuit. Neuroscience. 2014;282:248–57.

Horga G, Cassidy CM, Xu X, Moore H, Slifstein M, Van Snellenberg JX, et al. Dopamine-related disruption of functional topography of striatal connections in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:862–70.

Levitt JJ, Nestor PG, Levin L, Pelavin P, Lin P, Kubicki M, et al. Reduced structural connectivity in frontostriatal white matter tracts in the associative loop in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:1102–11.

McCutcheon R, Beck K, Jauhar S, Howes OD. Defining the locus of dopaminergic dysfunction in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and test of the mesolimbic hypothesis. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:1301–11.

Dandash O, Fornito A, Lee J, Keefe RS, Chee MW, Adcock RA, et al. Altered striatal functional connectivity in subjects with an at-risk mental state for psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:904–13.

Straub KT, Hua JPY, Karcher NR, Kerns JG. Psychosis risk is associated with decreased white matter integrity in limbic network corticostriatal tracts. Psychiatry Res: Neuroimaging. 2020;301:111089.

Howes OD, Shatalina E. Integrating the neurodevelopmental and dopamine hypotheses of schizophrenia and the role of cortical excitation-inhibition balance. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;92:501–13.

Patel PK, Leathem LD, Currin DL, Karlsgodt KH. Adolescent neurodevelopment and vulnerability to psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89:184–93.

Chung Y, Addington J, Bearden CE, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, Mathalon DH, et al. Use of machine learning to determine deviance in neuroanatomical maturity associated with future psychosis in youths at clinically high risk. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:960–8.

Di Biase MA, Cetin-Karayumak S, Lyall AE, Zalesky A, Cho KIK, Zhang F, et al. White matter changes in psychosis risk relate to development and are not impacted by the transition to psychosis. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:6833–44.

Asato MR, Terwilliger R, Woo J, Luna B. White matter development in adolescence: a DTI study. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:2122–31.

Tamnes CK, Ostby Y, Fjell AM, Westlye LT, Due-Tonnessen P, Walhovd KB. Brain maturation in adolescence and young adulthood: regional age-related changes in cortical thickness and white matter volume and microstructure. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:534–48.

Porter JN, Roy AK, Benson B, Carlisi C, Collins PF, Leibenluft E, et al. Age-related changes in the intrinsic functional connectivity of the human ventral vs. dorsal striatum from childhood to middle age. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2015;11:83–95.

Jung MH, Jang JH, Kang DH, Choi JS, Shin NY, Kim HS, et al. The reliability and validity of the Korean version of the structured interview for prodromal syndrome. Psychiatry Investig. 2010;7:257–63.

Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Cadenhead K, Cannon T, Ventura J, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:703–15.

Tziortzi AC, Haber SN, Searle GE, Tsoumpas C, Long CJ, Shotbolt P, et al. Connectivity-based functional analysis of dopamine release in the striatum using diffusion-weighted MRI and positron emission tomography. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24:1165–77.

Cho KI, Shenton ME, Kubicki M, Jung WH, Lee TY, Yun JY, et al. Altered thalamo-cortical white matter connectivity: probabilistic tractography study in clinical-high risk for psychosis and first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:723–31.

Park H, Kim M, Kwak YB, Cho KIK, Lee J, Moon SY, et al. Aberrant cortico-striatal white matter connectivity and associated subregional microstructure of the striatum in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:3460–7.

Brandizzi M, Valmaggia L, Byrne M, Jones C, Iwegbu N, Badger S, et al. Predictors of functional outcome in individuals at high clinical risk for psychosis at six years follow-up. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;65:115–23.

Lee TY, Kim SN, Correll CU, Byun MS, Kim E, Jang JH, et al. Symptomatic and functional remission of subjects at clinical high risk for psychosis: a 2-year naturalistic observational study. Schizophr Res. 2014;156:266–71.

Pelizza L, Di Lisi A, Leuci E, Quattrone E, Azzali S, Pupo S, et al. Subgroups of clinical high risk for psychosis based on baseline antipsychotic exposure: clinical and outcome comparisons across a 2-year follow-up period. Schizophr Bull. 2025;51:432–45.

Zhang T, Yang S, Xu L, Tang X, Wei Y, Cui H, et al. Poor functional recovery is better predicted than conversion in studies of outcomes of clinical high risk of psychosis: insight from SHARP. Psychol Med. 2020;50:1578–84.

Haber SN. Corticostriatal circuitry. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016;18:7–21.

Morris LS, Kundu P, Dowell N, Mechelmans DJ, Favre P, Irvine MA, et al. Fronto-striatal organization: defining functional and microstructural substrates of behavioural flexibility. Cortex. 2016;74:118–33.

Radua J, Schmidt A, Borgwardt S, Heinz A, Schlagenhauf F, McGuire P, et al. Ventral striatal activation during reward processing in psychosis: a neurofunctional meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1243–51.

Fornito A, Harrison BJ, Goodby E, Dean A, Ooi C, Nathan PJ, et al. Functional dysconnectivity of corticostriatal circuitry as a risk phenotype for psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:1143–51.

Kegeles LS, Abi-Dargham A, Frankle WG, Gil R, Cooper TB, Slifstein M, et al. Increased synaptic dopamine function in associative regions of the striatum in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:231–9.

Bloemen OJ, de Koning MB, Schmitz N, Nieman DH, Becker HE, de Haan L, et al. White-matter markers for psychosis in a prospective ultra-high-risk cohort. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1297–304.

Carletti F, Woolley JB, Bhattacharyya S, Perez-Iglesias R, Fusar Poli P, Valmaggia L, et al. Alterations in white matter evident before the onset of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:1170–9.

Wang C, Ji F, Hong Z, Poh JS, Krishnan R, Lee J, et al. Disrupted salience network functional connectivity and white-matter microstructure in persons at risk for psychosis: findings from the LYRIKS study. Psychol Med. 2016;46:2771–83.

Akouri-Shan L, Schiffman J, Millman ZB, Demro C, Fitzgerald J, Rouhakhtar PJR, et al. Relations among anhedonia, reinforcement learning, and global functioning in help-seeking youth. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47:1534–43.

Cressman VL, Schobel SA, Steinfeld S, Ben-David S, Thompson JL, Small SA, et al. Anhedonia in the psychosis risk syndrome: associations with social impairment and basal orbitofrontal cortical activity. NPJ Schizophrenia. 2015;1:15020.

Kimhy D, Gill KE, Brucato G, Vakhrusheva J, Arndt L, Gross JJ, et al. The impact of emotion awareness and regulation on social functioning in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Psychol Med. 2016;46:2907–18.

Macfie WG, Spilka MJ, Bartolomeo LA, Gonzalez CM, Strauss GP. Emotion regulation and social knowledge in youth at clinical high-risk for psychosis and outpatients with chronic schizophrenia: associations with functional outcome and negative symptoms. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2023;17:21–28.

Barber AD, Sarpal DK, John M, Fales CL, Mostofsky SH, Malhotra AK, et al. Age-normative pathways of striatal connectivity related to clinical symptoms in the general population. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85:966–76.

Walhovd KB, Tamnes CK, Bjornerud A, Due-Tonnessen P, Holland D, Dale AM, et al. Maturation of cortico-subcortical structural networks-segregation and overlap of medial temporal and fronto-striatal systems in development. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25:1835–41.

Larsen B, Verstynen TD, Yeh FC, Luna B. Developmental changes in the integration of affective and cognitive corticostriatal pathways are associated with reward-driven behavior. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28:2834–45.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Brain Science Convergence Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and the Basic Research Program of the Korea Brain Research Institute (KBRI), funded by the Ministry of Science & ICT (grant nos. RS-2023-00266120 and 25-BR-05-05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EC and MK conceived and designed the study. MK and JSK supervised all the processes. MK, JJ, and JSK collected data and performed clinical evaluation. EC and HP performed image processing and data analysis. EC and MK wrote the manuscript. JJ, HP, and JSK revised the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All participants received thorough explanations of the study and provided written informed consent (IRB no. H-1110-009-380). For participants younger than 18 years, informed consent was also obtained from their parents. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB no. H-2408-158-1565).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choe, E., Park, H., Jang, J. et al. Differential trajectories of corticostriatal structural connectivity in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis according to functional outcome. Transl Psychiatry 15, 319 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03567-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03567-1