Abstract

Cognitive impairment is an important but often under-researched symptom in psychosis. Both psychosis and cognition are highly heritable and there is evidence of a genetic effect on the relationship between them. Using samples of adults (N = 4 506) and children (N = 10 981), we investigated the effect of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder polygenic scores on cognitive performance, and intelligence and educational attainment polygenic scores on psychosis presentation. Schizophrenia polygenic score was negatively associated with visuospatial processing in adults (beta: −0.0569; 95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.0926, −0.0212) and working memory (beta: −0.0432; 95% CI: −0.0697, −0.0168), processing speed (beta: −0.0491; 95% CI: −0.0760, −0.0223), episodic memory (betas: −0.0581 to −0.0430; 95% CIs: −0.0847, −0.0162), executive functioning (beta: −0.0423; 95% CI: −0.0692, −0.0155), fluid intelligence (beta: −0.0583; 95% CI: −0.0847, −0.0320), and total intelligence (beta: −0.0458; 95% CI: −0.0709, −0.0206) in children. Bipolar disorder polygenic score was not associated with any cognitive domains studied. Lower polygenic scores for intelligence were associated with greater odds of psychosis in adults (odds ratio [OR]: 0.886; 95% CI: 0.811–0.968). In children, lower polygenic scores for both intelligence (OR: 0.829; 95% CI: 0.777–0.884) and educational attainment (OR: 0.771; 95% CI: 0.724–0.821) were associated with greater odds of psychotic-like experiences. Our findings suggest that polygenic scores for both cognitive phenotypes and psychosis phenotypes are implicated in the relationship between psychosis and cognitive performance. Further research is needed to determine the direction of this effect and the mechanisms by which it occurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are two of the most prevalent disorders that fall under the broader category of “psychosis”, a term used to describe disorders characterised by alterations to an individual’s thoughts and/or perceptions [1]. They are also two of the most heritable psychiatric disorders, with heritability rates between 75–80% [2, 3] and a large overlap in the genetic variants associated with each [4].

Though the most common symptoms are hallucinations and delusions, impairments in cognitive functioning are also seen in the majority of individuals with psychosis [5]. This is an important yet often overlooked symptom as associations have been found between poorer cognitive functioning and poorer functional outcomes. Cognitive functioning is also heritable, with heritability estimates of approximately 50% [6], which appear to be similar in both people with psychosis and the general population [7, 8]. Cognitive impairments can also be seen in the unaffected relatives of those with psychosis [9,10,11,12] as well as individuals at clinical-high risk of psychosis [13, 14]. These factors have led to cognitive performance (both broadly and within individual cognitive domains) being proposed as an endophenotype for psychosis [15]. Endophenotypes are measurable traits that can be used to “bridge the gap” between the genetic components of a disorder and its symptom presentation and help understand the mechanisms that lead from genotype to phenotype [16, 17].

Meta-analytic evidence suggests that schizophrenia polygenic scores are significantly associated with overall cognitive performance in general population samples [18]. However, this pattern does not appear when samples are restricted to those with psychosis, possibly because the effect is already captured by diagnosis or simply due to the smaller sample sizes [19, 20]. Evidence is mixed on the exact components of cognitive ability affected by schizophrenia polygenic scores [21]. The strongest evidence is for a negative effect on performance IQ, attention, and premorbid intelligence [18], while verbal memory, crystalised intelligence, category fluency, and educational attainment show less association with the polygenic scores [22,23,24,25]. For bipolar disorder polygenic scores, the literature is even more mixed, with some evidence suggesting a negative effect on childhood executive functioning, performance IQ, and processing speed [26]. Other evidence has produced little association [19, 22, 27, 28], and some have found positive associations with creativity and educational attainment [29]. Therefore, there is room for further investigation into the exact components of cognitive ability that show associations with polygenic scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Looking in the opposite direction, the polygenic scores for cognitive performance are associated with performance on cognitive tests in population samples [19, 30, 31], individuals with psychosis [19, 30,31,32], and ultra-high risk individuals [33], suggesting that cognition is influenced by similar genetic mechanisms irrespective of psychosis risk [19]. These polygenic scores have also been shown to be associated with psychosis presentation as polygenic scores for childhood intelligence [34], performance IQ [35], and general cognitive ability [36] found to be lower in individuals with psychosis compared to controls. This suggests that the effect of genetic factors on the relationship between psychosis and cognitive impairment may be bidirectional.

The majority of research on the relationship between psychosis and cognition has been conducted in adult samples, which is unsurprising given the age of onset for psychotic disorders. However, schizophrenia is a neurodevelopmental disorder [37, 38], cognitive impairments can be seen in the prodromal phase of psychosis [39,40,41], and the transition to psychosis is not typically associated with further cognitive decline [42, 43]. Therefore, extending this research beyond adulthood could add depth to our understanding of the genetic mechanisms behind the relationship between psychosis and cognitive performance. Psychotic-like experiences in childhood have been associated with poorer cognitive functioning [44, 45] and polygenic scores for cognitive performance and educational attainment have each been negatively associated with these psychotic-like experiences [46].

The aim of the present study was to examine this bidirectional effect of polygenic scores on the relationship between psychosis and cognitive performance in the same samples and in both adults and children. We examined the effect of polygenic scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder on performance within a range of individual cognitive domains as well as the effect of polygenic scores for cognitive performance and educational attainment on psychosis presentation.

Method and materials

Participants

Psychosis endophenotypes international consortium (PEIC)

PEIC is a collaborative effort from multiple sites across Europe (UK, the Netherlands, Spain, Germany) and Australia, comprising data from individuals with a diagnosis of psychosis (bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder; hereafter patients), their unaffected relatives, and healthy control participants. All were of European ancestry [28, 47]. Relatives and controls were not excluded if they had a personal history of a non-psychotic psychiatric disorder, as long as they were off psychotropic medication for at least 12 months before assessment. Exclusion criteria (for all clinical groups) included a history of neurological disease or previous loss of consciousness due to head injury [9].

Adolescent brain cognition development (ABCD)® study

The ABCD Study® is a longitudinal study from the USA that aims to investigate the impact of various factors on brain development and health/social outcomes. A population-representative sample of children aged 9–10 years was recruited between 2016 and 2018 [48]. Participants were excluded if they were not fluent in English, had a history of traumatic brain injury, or a current diagnosis of moderate/severe autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, intellectual disability, or substance use disorders [49]. All data used here were taken from baseline assessments.

Genotyping, quality control, and imputation

PEIC

DNA was extracted from blood samples of 6 935 participants and sent to the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (Cambridge, UK) for initial processing and quality control (QC). After imputation, 6 215 801 SNPs and 4 835 participants remained. Further details available in Bramon et al. [47] and Supplementary Information.

ABCD study®

DNA was extracted from blood/saliva samples of 11 880 participants at the Rutgers University Cell and DNA Repository (RUCDR; New Jersey, USA). After post-imputation QC, 11 229 083 SNPs and 11 017 participants remained. Further detail available in Uban et al. [50], Wang et al. [49] and Supplementary Information, as well at https://nda.nih.gov/study.html?id=901.

Relationship inference and principal component analysis

PEIC and ABCD study®

The GENESIS R/Bioconductor package [51, 52] was used to account for familial relatedness and population structure. An unadjusted kinship matrix was generated first using KING-robust 2.2.5 [53] to infer the relatedness of each pair of participants. The SNPRelate package in R 4.0.2 [54] was used to analyse the genotyped data alongside this kinship matrix to estimate ancestrally representative principal components (PCs). An adjusted kinship matrix was then generated to account for these PCs, allowing for an estimation of familial relatedness independent of ancestry. Further details available in Supplementary Information and Wang et al. [49].

Polygenic score generation

All polygenic scores were generated using PRS-CSx [55]. Reference panels from the 1000 Genomes Project [56] that best matched the ancestries present in the original genome-wide association studies (GWAS) were used (bipolar disorder, educational attainment, and intelligence polygenic scores: European panel; schizophrenia polygenic score: European, East Asian, African, and Admixed American panels; see Supplementary Information). Scores were standardised against the sample mean (in the PEIC sample, the control group mean).

For schizophrenia and bipolar disorder polygenic scores, summary statistics from the Psychiatric Genomic Consortium (PGC) analyses were used [57, 58]. As the PEIC data was used in the PGC schizophrenia discovery sample, summary statistics were obtained that excluded this sample to avoid overlap. For educational attainment polygenic scores, summary statistics from Lee et al. [59] were used. For the intelligence polygenic scores, summary statistics from Savage et al. [60] were used.

Cognitive tests

PEIC

Three tests were administered: block design and digit span from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, revised version (WAIS-R) [61] or third edition (WAIS-III) [62], and the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) [63].

ABCD study®

Participants completed 11 neurocognitive tests, seven from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Toolbox® (Picture Vocabulary; Oral Reading Recognition; Pattern Comparison; List Sorting; Picture Sequence; Flanker; Dimensional Change Card Sort) and four additional tests (RAVLT; Cash Choice Task; Little Man Task; Matrix Reasoning) [64].

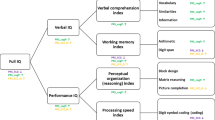

The NIH Toolbox® tests create three composite scores: Crystalised Intelligence, Fluid Intelligence, and Total Intelligence [64]. The cognitive domains that each test measures and further detail on each test is available in Supplementary Information.

Psychosis outcome

PEIC

All participants underwent a structured clinical interview with a psychiatrist to confirm (for patients) or rule out (for relatives and controls) the presence of a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder [28, 47]. This led to three clinical groups: patients, relatives, and controls. These groups were used as the psychosis outcome in the adult sample.

ABCD study®

Responses on the Prodromal Questionnaire–Brief Child Version (PQ-BC), a 21-item self-report questionnaire of psychotic-like experiences in the past month, were used to measure psychotic-like experiences. Each item has three parts: whether they experienced the symptom; if yes, whether it was distressing; and, if yes, how distressing on a scale of 1 (“not very bothered”) to 5 (“extremely bothered”). Scores of 3 (“moderately bothered”) or more were classed as significantly distressing [45]. Three levels of psychotic-like experiences were created as the outcome in the child sample, increasing in severity: psychotic-like experiences; distressing psychotic-like experiences; and significantly distressing psychotic-like experiences.

Statistical analyses

After removing participants with incomplete data, 4 506 participants remained in the PEIC sample and 10 981 remained in the ABCD Study® sample. Mixed model regression analyses (linear/logistic) were used to investigate the effect of polygenic scores on cognitive performance and psychosis presentation. Age, sex, and ancestry PCs were included as fixed effects (as well as research site for all PEIC analyses, and clinical group in the cognitive performance PEIC analyses); the adjusted kinship matrix was included as a random effect. Linear cognitive test scores were standardised against the group mean in the ABCD Study® sample analyses and against the control group mean in the PEIC sample analyses. Interaction and subgroup analyses were also conducted within the PEIC sample to determine whether the effect of polygenic scores differed between the clinical groups.

A multiple testing correction of 0.05/4 (three cognitive tests and group status prediction) was applied to the analyses carried out with the PEIC sample, leaving an adjusted significance threshold of p < 0.0125. In the ABCD Study® dataset, cognitive tests were grouped by domain. This resulted in seven domains (Supplementary Table S1) which, combined with the psychotic-like experience prediction, lead to an adjusted significance threshold of p < 0.00625 (0.05/8). Uncorrected p-values are reported but interpreted using the respective adjusted threshold.

We also used a Support Vector Machine (SVM) supervised machine learning algorithm to predict the group status in both the adult sample (patient, relative, or control) and child sample (psychotic-like experience groups) from cognition-related polygenic scores and demographic parameters (age, sex, ancestry PCs, research site), following the method from Bracher Smith et al. [65]. This was included as a robust and replicable baseline to validate and benchmark the regression. To assess the relative importance of the polygenic scores compared to demographic predictors on clinical group status, the SVM model was further inspected using permutation feature importance [66]. Further details of these analyses can be found in the Supplementary Information.

PEIC

Participants gave written informed consent and Institutional Review Board (IRBs) at each collecting site approved the study. Laboratory and data analyses across sites were approved under the following IRBs: The UK National Health Service Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (19/LO/1403 and 03/11/090); and the Ethics Committee at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience at King’s College London (references 038/00 and 011/99).

ABCD study®

Informed assent/consent was obtained from participants and their parents at the research centre they were recruited at. Ethical approval of the research protocol was provided for most sites by a central IRB at the University of California, San Diego (IRB# 160091); some sites obtained local IRB approval [67].

Results

Demographics

Demographic data for participants in the PEIC sample are presented in Table 1 and for the ABCD Study® sample in Table 2. In both samples, the split between males and females was relatively equal (though in the PEIC sample subgroups, there were more male patients and more female relatives). In the ABCD sample, just over half were of White ethnicity.

Cognitive test performance

Details of average cognitive performance for both the PEIC sample and ABCD Study® sample are available in the Supplementary Information and Supplementary Tables S2–S4. Correlation matrices displaying the correlation between scores on the different tests included in the study are displayed in Supplementary Figure S1 (PEIC sample) and Supplementary Figure S2 (ABCD Study® sample).

Effect of polygenic scores on cognitive performance

Effect of polygenic scores on cognitive performance: PEIC (Adult) sample

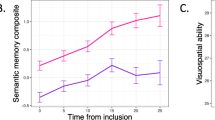

Schizophrenia polygenic score was negatively associated with block design performance (mean difference: -0.0569; 95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.0926, −0.0212; p = 0.00179), but no associations were identified with other cognitive tests (p values > 0.356). Bipolar disorder polygenic scores showed no significant associations after multiple testing correction (p values > 0.0219). Intelligence (p values < 0.000165) and educational attainment (p values < 0.000897) polygenic scores were each significantly positively associated with performance on all tests (Fig. 1; Supplementary Tables S5 and S6).

Effect of psychosis-related and cognition-related polygenic scores on cognitive test performance in adults, while controlling for the effect of age, gender, clinical group (patient/relative/control), research site, ancestry (the first four ancestry principal components), and participant inter-relatedness (kinship matrix). Scores have been standardised using the mean and standard deviation from the control group. Standardised values are given in Supplementary Table S5; non-standardised values are given in Supplementary Table S6. PEIC Psychosis Endophenotype International Consortium, RAVLT Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Task.

Interaction analyses between polygenic scores and clinical group were non-significant, suggesting no difference in the effect of the polygenic scores between the clinical groups. Interaction and subgroup analyses are discussed in detail in Supplementary Tables S7, S8, S17, and S18 and the Supplementary Information.

Effect of polygenic scores on cognitive performance: ABCD study® (Child) sample

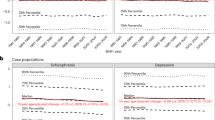

Schizophrenia polygenic score was negatively associated with Fluid Intelligence (mean difference: −0.0583; 95% CI: −0.0847, −0.0320; p = 1.44 × 10−5) and Total Intelligence (mean difference: −0.0458; 95% CI: −0.0709, −0.0206; p = 0.000362) composite scores, but not Crystalised Intelligence composite scores (p = 0.162). For individual tests, higher schizophrenia polygenic score was associated with lower scores on: Dimensional Change Card Sort (mean difference: −0.0423; 95% CI: −0.0692, −0.0155, p = 0.00201), List Sorting (mean difference: −0.0432; 95% CI: −0.0697, −0.0168; p = 0.00136), Pattern Comparison (mean difference: −0.0491; 95% CI: −0.0760, −0.0223; p = 0.000342), and Picture Sequence (mean difference: −0.0430; 95% CI: −0.0697, −0.0162; p = 0.00164) from the NIH Toolbox® (four of the five tests that comprise the Fluid Intelligence composite score), as well as immediate (mean difference: −0.0437, 95% CI: −0.0699, −0.0174; p = 0.00111), short-delayed (mean difference: −0.0581; 95% CI: −0.0847, −0.0315; p = 1.92 × 10−5), and long-delayed (mean difference: −0.0483; 95% CI: −0.0750, −0.0216; p = 0.000397) recall on the RAVLT (Fig. 2).

Effect of psychosis-related and cognition-related polygenic scores on cognitive test performance in children, while controlling for the effect of age, gender, ancestry (the first eight ancestry principal components), and participant inter-relatedness (kinship matrix). Scores have been standardised using the mean and standard deviation from the whole sample. Standardised values are given in Supplementary Table S9 and S11; non-standardised values are given in Supplementary Table S10 and S12. Note: “Little Man Task (Correct)” refers to the percentage of participants’ responses were correct during the task. “Little Man Task (Incorrect)” refers to the percentage of participants’ responses were incorrect. Cash Choice Task effect is the log-transformed result from a logistic regression analysis. Effect > 0 indicates greater odds of choosing the delayed gratification option ($115 in three months); effect < 0 indicates greater odds of choosing the immediate gratification option ($75 in three days). Log-transformed values are given in Supplementary Table S13; logistic regression results are given in Supplementary Table S14. ABCD Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development, RAVLT Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Task.

There was no significant effect of bipolar disorder polygenic score on performance in any of the cognitive tests or composite scores after correction for multiple comparisons (p values > 0.0185). Intelligence (p values < 2.71 × 10−5) and educational attainment (p values < 0.00381) polygenic scores were significantly associated with performance on all tests and composites. Full results are presented in Supplementary Tables S9–S14.

Effect of polygenic scores on psychosis presentation

Effect of polygenic scores on psychosis presentation: PEIC (Adult) sample

The logistic regression models showed that intelligence polygenic score was able to distinguish between patients and controls (odds ratio [OR]: 0.886; 95% CI: 0.811–0.968; p = 0.00719). There was also a trend towards distinguishing between relatives and controls (p = 0.0190; Fig. 3), but this did not pass the adjusted significance threshold (p < 0.0125). Educational attainment polygenic scores was a poor predictor of clinical group in the adult sample (p values > 0.445; Supplementary Table S15).

Effect of psychosis-related and cognition-related polygenic scores on the odds of being in the comparison group (i.e. patient, relative, patient, respectively from top to bottom) compared to the odds of being in the comparison group (i.e. control, control, relative, respectively). Values are given in Supplementary Table S15. PEIC Psychosis Endophenotypes International Consortium.

Both bipolar disorder polygenic scores (p values < 2.38 × 10−5) and schizophrenia polygenic scores (p values < 6.80 × 10−7) were able to significantly distinguish between all clinical groups.

In the machine learning analysis, while the SVM models including intelligence polygenic scores and educational attainment polygenic scores were each able to distinguish between patients and controls (median area under the receiver operating characteristic [AUROCmedian]: 0.847 and AUROCmedian: 0.856, respectively) and between patients and relatives (AUROCmedian: 0.781 and AUROCmedian: 0.752, respectively) with high accuracy, the relative importance of the polygenic scores was low. This suggests the model’s performance was driven by the covariates included in the model. Further details available in the Supplementary Information.

Effect of polygenic scores on psychosis presentation: ABCD Study® (Child) sample

The regression models showed that educational attainment polygenic score significantly distinguished between children who experienced psychotic-like experiences at baseline and those who did not (OR: 0.771; 95% CI: 0.724–0.821; p = 5.86 × 10−16), those who experienced distressing psychotic-like experiences and those who did not (OR: 0.813, 95% CI: 0.764–0.864, p = 5.48 × 10−11), and those who experienced significantly distressing psychotic-like experiences and those who did not (OR: 0.769; 95% CI: 0.717–0.826; p = 3.87 × 10−13) (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S16). Educational attainment polygenic score was also significantly negatively associated with the number of each category of psychotic-like experiences reported (p values < 2.52 × 10−11; Supplementary Table S16).

Effect of psychosis-related and cognition-related polygenic scores on the odds of experiencing at least one of the given types of psychotic-like experiences (i.e. odds of experiencing at least one psychotic-like experience, at least one distressing psychotic-like experience, at least one significantly distressing psychotic-like experience, respectively from top to bottom) compared to the odds of not having such experiences. Psychotic-like experiences measured using the Prodromal Questionnaire–Brief Child Version (PQ-BC). Values given in Supplementary Table S16. ABCD Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development.

Intelligence polygenic score was also negatively associated with all psychotic-like experience outcomes in the regression models. A greater intelligence polygenic score was associated with decreased odds of psychotic-like experiences (OR: 0.829; 95% CI: 0.777–0.884; p = 1.35 × 10−8), distressing psychotic-like experiences (OR: 0.853; 95% CI: 0.800–0.909; p = 1.02 × 10−6), and significantly distressing psychotic-like experiences (OR: 0.795; 95% CI: 0.740–0.855; p = 6.32 × 10−10) (Fig. 4), as well as the number of each type of psychotic-like experience reported (p values < 3.83 × 10−6; Supplementary Table S16).

For both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder polygenic scores, there was only one significant result after correcting for multiple comparisons. In both cases, this was the distinction between those who experienced distressing psychotic-like experiences and those who did not. Higher schizophrenia polygenic scores (OR: 1.08; 95% CI: 1.02–1.14; p = 0.00939) and bipolar disorder polygenic scores (OR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.22; p = 0.00817) were associated with increased odds of reporting such experiences.

When the group classification analyses were carried out using the full SVM model, each performed at near the 0.5 (chance) level (AUROC: 0.550–0.613). Further detail available in the Supplementary Information.

Discussion

We aimed to examine the effect of polygenic scores for both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder on cognitive performance within specific cognitive domains, examine the effect of polygenic scores for intelligence and educational attainment on psychosis presentation, and extend previous research in this area by exploring these associations in both adults and children. Our results suggest that schizophrenia polygenic scores and bipolar disorder polygenic scores have different effects on cognitive performance, and that these effects differ across cognitive domains and possibly across different stages of life. In terms of cognition-related polygenic scores, only intelligence polygenic scores were able to distinguish between clinical groups (psychosis cases, unaffected relatives, and healthy controls) in the adult sample, while both the educational attainment and intelligence polygenic scores distinguished between the psychotic-like experience groups in the child sample. However, when these group distinction analyses were carried out using the machine learning model, the relative importance of the polygenic scores was low, suggesting their impact on prediction is minimal.

Influence of polygenic scores for psychosis on cognitive performance

Our evidence supports previously reported negative associations between schizophrenia polygenic scores and cognitive performance [18, 33, 34]. This effect appeared to differ both between adults and children and between the different cognitive domains. In the adult sample, higher schizophrenia polygenic scores were associated with poorer performance on the visuospatial processing task (block design), but not with the tests of working memory or episodic memory. In the child sample, higher schizophrenia polygenic scores were associated with poorer language ability, working memory, processing speed, and episodic memory, while there was no evidence of association with visuospatial processing. Methodological factors may have contributed to this difference (e.g. differences in the tests used, different sample sizes, controlling for clinical group in the PEIC analyses), but there is a possibility these findings represent a difference in the effect of schizophrenia risk over time or distinct maturational paths of the individual cognitive domains. There is conflicting evidence on the effect of schizophrenia polygenic scores on the domains that differed between the adult and child samples [23, 35, 68, 69], suggesting further research is needed to pinpoint these associations.

In both samples, we found limited evidence for an association between bipolar disorder polygenic scores and cognitive performance, in line with previous evidence [22, 26,27,28, 70]. One test showed a stronger association with bipolar disorder polygenic scores than schizophrenia polygenic scores: the Cash Choice task (though this result did not pass the adjusted significance threshold). Bipolar disorder polygenic score was associated with greater odds of choosing the immediate gratification option ($75 in three days) compared to delayed gratification ($115 in three months). This suggests greater impulsivity, which has been linked with bipolar disorder specifically [71, 72] so may serve as a mania/bipolar disorder-specific marker, though some evidence suggests it is associated with psychosis more generally [73].

While these findings replicate associations found in other samples, they cannot provide detail on the causal relationship between schizophrenia polygenic scores and cognitive performance. While a direct effect is possible, it may also be that the schizophrenia-associated genetic variants sensitise the individual to other factors (genetic or non-genetic) that then lead to cognitive impairment [43]. Further research that specifically aims to determine the causality of this relationship is needed to increase our understanding.

Influence of polygenic scores for cognition on psychosis presentation

Intelligence polygenic scores showed a stronger association with psychosis outcomes in both adults and children compared to educational attainment polygenic scores. Intelligence polygenic score distinguished adult patients from controls, though with a smaller effect size than schizophrenia or bipolar disorder polygenic scores. There was also a trend towards distinguishing relatives from controls, though this did not pass the adjusted significance threshold for multiple comparisons. The odds ratio for distinguishing between patients and relatives, however, was almost exactly 1, suggesting that in terms of intelligence polygenic score, relatives and patients are more alike compared to controls. This differs from the schizophrenia polygenic score, which showed a greater effect size in distinguishing between patients and relatives compared to relatives and controls. Intelligence polygenic score also distinguished each category of psychotic-like experience in the child sample, while both the schizophrenia and bipolar disorder polygenic scores were each only able to distinguish one category (distressing psychotic-like experiences) and with smaller effect sizes. Educational attainment polygenic score was also negatively associated with all categories of psychotic-like experiences in the child sample, but did not distinguish between any of the clinical groups in the adult sample. This aligns previous findings that polygenic scores for cognitive performance/intelligence are more associated with schizophrenia case-status than educational attainment polygenic scores [30, 31, 45], possibly due to the non-genetic factors also involved in educational attainment [46, 74, 75]. However, the variance explained in psychosis outcomes was extremely small. Also, while the effect of the polygenic scores in the regression models, controlling for covariates, was significant, the machine learning analyses did not find the polygenic scores to contribute considerably in the adult sample and analyses performed at chance level in the child sample. While there may be a statistically significant effect of cognition-related polygenic scores on psychosis presentation, the clinical implications may be minimal.

We found a changing pattern of associations with psychosis presentation, whereby cognition-related polygenic scores were more strongly associated with psychotic-like experiences in childhood than psychosis-related polygenic scores, but psychosis-related polygenic scores were more strongly associated with case-control status in adulthood than the cognition-related polygenic scores. This raises questions about the similarities and differences between cognition-related and psychosis-related polygenic scores, the pathways through which they exert their phenotypic effects, and how this may differ across the lifespan. However, caution should also be taken when interpreting the associations in the child sample, as the differences in results may also be due to different phenotype classification. Although the Prodromal Questionnaire–Brief Child Version (PQ-BC) has been validated as a measure of early risk for psychosis [76], these symptoms are not necessarily indicative of psychosis in adulthood [77]. In the child sample, the proportion that reported experiencing at least one psychotic-like experience was well over the proportion expected to develop psychosis (and it should be noted that a formal, current diagnosis of schizophrenia was an exclusion criterion in the ABCD Study®, though the prevalence within this age group would be expected to be very low). This may be a factor in the difference in effect of the cognition-related polygenic scores in the child and adult samples. Childhood psychotic-like experiences may instead be indicative of an increased risk of later psychopathology more generally [78] rather than a predictor of those who will go on to meet criteria for a psychotic disorder. Cognition-related (particularly intelligence) polygenic scores may be able to provide an early indicator of who may continue experiencing such symptoms and develop psychosis in adulthood.

The mechanisms by which cognition-related polygenic scores are associated with psychosis may be rooted in the individual’s cognitive reserve [79]. Those with lower cognition-related polygenic scores may have a reduced cognitive reserve, which may affect a range of factors should they develop symptoms of psychosis in adulthood. Cognition-related polygenic scores (particularly those for cognitive performance/intelligence) may therefore act as a moderator on the relationship between genetic risk for psychosis and symptom presentation in adulthood. In a similar way, the polygenic score for schizophrenia resilience (common variants that may ameliorate the effect of schizophrenia risk variants in the context of a high schizophrenia polygenic risk score [80]) has been positively associated with cognitive performance across a range of cognitive domains [81], suggesting the variants that appear to have a protective effect on schizophrenia development may exert their effect, at least in part, through cognitive pathways.

Limitations

While we made efforts to increase the ancestry diversity by using all participants in the ABCD Study®, the accuracy of the polygenic score calculations are limited by the GWAS discovery samples, which remain mostly European [57,58,59,60]. Efforts are in place to carry out GWASs in global populations beyond Europe [82,83,84]. Methods of generating polygenic scores that allow summary statistics from multiple ancestries to be used together, such as PRS-CSx, also help to improve accuracy when GWAS summary statistics from multiple ancestry groups are available [55, 85, 86]. However, without diversity in the first step of the process (i.e. the discovery GWAS samples), polygenic scores will remain less accurate in non-European ancestry groups.

Another limitation is that polygenic scores only account for common variants associated with an outcome. The SNP heritability for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and intelligence, are each reported as around 20% [57, 58, 60], despite overall heritability rates of 60–80% for schizophrenia [57], 60–85% for bipolar disorder [58], and 50% for intelligence [60], which suggests that not all of the heritability is being accounted for by the common variants identified in GWAS. Other genetic factors, including copy number variants (CNVs), are known to be associated with both psychosis and cognitive functioning [87, 88]. The use of microarray methods to genotype GWAS participants has also been suggested to play a role in the “missing heritability”; it is hoped that moving towards whole genome sequencing approaches may reduce this [89].

In our adult sample, individuals with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (9% of the patient group) must have also experienced psychosis to be included in the cohort. These individuals may represent a more homogenous and severe subset that may be more similar, phenotypically and potentially genetically, to those with schizophrenia compared to the overall bipolar disorder population. This, as well as the low proportion of those with bipolar disorder compared to schizophrenia, may partially explain the stronger associations between schizophrenia polygenic scores and outcomes in this sample compared to bipolar disorder polygenic scores.

Implications

These results, if replicated, add to the growing evidence for a genetic component in the relationship between psychosis and cognitive impairment [18]. As cognitive impairment in psychosis is associated with poorer health outcomes [5, 90, 91], such evidence may help to identify those at risk. Future research should prioritise using samples of different ancestry groups. As polygenic profiling becomes more widely available, without these efforts, such techniques may further exacerbate health disparities/inequity instead of improving healthcare [92, 93].

Finally, longitudinal studies such as the ABCD Study® provide the opportunity for developmental research in this field. As participants will be followed up for up to 10 years (from age 9–10 until 19–20), patterns in both cognitive performance and psychosis presentation can be followed across the developmental period. This timeframe also covers the period previously used to examine the change in heritability of cognitive functioning [94], meaning this sample could be used to examine whether this change affects the impact of genetic factors on the relationship between psychosis and cognition.

Conclusion

We found evidence that both cognition-related and psychosis-related polygenic scores are implicated in the association between psychosis and cognitive functioning, and that this can be seen in both adults and children. Cognition-related polygenic scores were more strongly associated with psychotic-like experiences in childhood than psychosis-related polygenic scores, but this association reversed when distinguishing adults with psychosis from controls, suggesting the contribution of genetic variants associated with each phenotype on the presentation of psychosis may differ over the life course. Further research is needed to pinpoint the causal effects in these relationships and the mechanisms through which they occur.

Data availability

The data used to generate the results are available upon request.

Code availability

The code used to generate the results is available upon request.

References

Overview - Psychosis. https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/psychosis/overview/, 2023, Date Accessed: 06-Aug-2025.

Anderson IM, Haddad PM, Scott J. Bipolar disorder. BMJ. 2012;345:e8508.

Hilker R, Helenius D, Fagerlund B, Skytthe A, Christensen K, Werge TM, et al. Heritability of schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum based on the nationwide danish twin register. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83:492–8.

Smeland OB, Bahrami S, Frei O, Shadrin A, O’Connell K, Savage J, et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals extensive genetic overlap between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and intelligence. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:844–53.

McCleery A, Nuechterlein KH. Cognitive impairment in psychotic illness: prevalence, profile of impairment, developmental course, and treatment considerations. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2019;21:239–48.

Plomin R, von Stumm S. The new genetics of intelligence. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19:148–59.

Antila M, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Kieseppa T, Soronen P, Palo OM, Paunio T, et al. Heritability of cognitive functions in families with bipolar disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:802–8.

Blokland GAM, Mesholam-Gately RI, Toulopoulou T, Del Re EC, Lam M, DeLisi LE, et al. Heritability of neuropsychological measures in schizophrenia and nonpsychiatric populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43:788–800.

Blakey R, Ranlund S, Zartaloudi E, Cahn W, Calafato S, Colizzi M, et al. Associations between psychosis endophenotypes across brain functional, structural, and cognitive domains. Psychol Med. 2018;48:1325–40.

Hoff AL, Svetina C, Maurizio AM, Crow TJ, Spokes K, DeLisi LE. Familial cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;133B:43–49.

Ma X, Wang Q, Sham PC, Liu X, Rabe-Hesketh S, Sun X, et al. Neurocognitive deficits in first-episode schizophrenic patients and their first-degree relatives. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:407–16.

Snitz BE, Macdonald AW 3rd, Carter CS. Cognitive deficits in unaffected first-degree relatives of schizophrenia patients: a meta-analytic review of putative endophenotypes. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:179–94.

Catalan A, Salazar de Pablo G, Aymerich C, Damiani S, Sordi V, Radua J, et al. Neurocognitive functioning in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:859–67.

Seidman LJ, Giuliano AJ, Smith CW, Stone WS, Glatt SJ, Meyer E, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in adolescents and young adults at genetic risk for schizophrenia and affective psychoses: results from the Harvard and Hillside Adolescent High Risk Studies. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:507–24.

Donati FL, D’Agostino A, Ferrarelli F. Neurocognitive and neurophysiological endophenotypes in schizophrenia: an overview. Biomarkers Neuropsychiatry. 2020;3:100017.

Gottesman II, Gould TD. The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: etymology and strategic intentions. Am J Psychiatr. 2003;160:636–45.

Gould TD, Gottesman II. Psychiatric endophenotypes and the development of valid animal models. Genes Brain Behav. 2006;5:113–9.

Mallet J, Le Strat Y, Dubertret C, Gorwood P. Polygenic risk scores shed light on the relationship between schizophrenia and cognitive functioning: review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9:341.

Richards AL, Pardinas AF, Frizzati A, Tansey KE, Lynham AJ, Holmans P, et al. The relationship between polygenic risk scores and cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46:336–44.

Schaupp SK, Schulze TG, Budde M. Let’s talk about the association between schizophrenia polygenic risk scores and cognition in patients and the general population: a review. J Psychiatr Brain Sci. 2018;3:12.

Mistry S, Harrison JR, Smith DJ, Escott-Price V, Zammit S. The use of polygenic risk scores to identify phenotypes associated with genetic risk of schizophrenia: Systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:2–8.

Comes AL, Senner F, Budde M, Adorjan K, Anderson-Schmidt H, Andlauer TFM, et al. The genetic relationship between educational attainment and cognitive performance in major psychiatric disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9:210.

Engen MJ, Lyngstad SH, Ueland T, Simonsen CE, Vaskinn A, Smeland O, et al. Polygenic scores for schizophrenia and general cognitive ability: associations with six cognitive domains, premorbid intelligence, and cognitive composite score in individuals with a psychotic disorder and in healthy controls. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:416.

Escott-Price V, Bracher-Smith M, Menzies G, Walters J, Kirov G, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC. Genetic liability to schizophrenia is negatively associated with educational attainment in UK Biobank. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:703–5.

Ohi K, Nishizawa D, Sugiyama S, Takai K, Kuramitsu A, Hasegawa J, et al. Polygenic risk scores differentiating schizophrenia from bipolar disorder are associated with premorbid intelligence in schizophrenia patients and healthy subjects. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;24:562–9.

Mistry S, Escott-Price V, Florio AD, Smith DJ, Zammit S. Investigating associations between genetic risk for bipolar disorder and cognitive functioning in childhood. J Affect Disord. 2019;259:112–20.

Liebers DT, Pirooznia M, Seiffudin F, Musliner KL, Zandi PP, Goes FS. Polygenic risk of schizophrenia and cognition in a population-based survey of older adults. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:984–91.

Ranlund S, Calafato S, Thygesen JH, Lin K, Cahn W, Crespo-Facorro B, et al. A polygenic risk score analysis of psychosis endophenotypes across brain functional, structural, and cognitive domains. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2018;177:21–34.

Power RA, Steinberg S, Bjornsdottir G, Rietveld CA, Abdellaoui A, Nivard MM, et al. Polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder predict creativity. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:953–5.

Shafee R, Nanda P, Padmanabhan JL, Tandon N, Alliey-Rodriguez N, Kalapurakkel S, et al. Polygenic risk for schizophrenia and measured domains of cognition in individuals with psychosis and controls. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:78.

Sorensen HJ, Debost JC, Agerbo E, Benros ME, McGrath JJ, Mortensen PB, et al. Polygenic risk scores, school achievement, and risk for schizophrenia: a danish population-based study. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84:684–91.

Legge SE, Cardno AG, Allardyce J, Dennison C, Hubbard L, Pardinas AF, et al. Associations between schizophrenia polygenic liability, symptom dimensions, and cognitive ability in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:1143–51.

He Q, Jantac Mam-Lam-Fook C, Chaignaud J, Danset-Alexandre C, Iftimovici A, Gradels Hauguel J, et al. Influence of polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia and resilience on the cognition of individuals at-risk for psychosis. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:518.

Ohi K, Takai K, Kuramitsu A, Sugiyama S, Soda M, Kitaichi K, Shioiri T. Causal associations of intelligence with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a Mendelian randomization analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64:e61.

Hubbard L, Tansey KE, Rai D, Jones P, Ripke S, Chambert KD, et al. Evidence of common genetic overlap between schizophrenia and cognition. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:832–42.

Lencz T, Knowles E, Davies G, Guha S, Liewald DC, Starr JM, et al. Molecular genetic evidence for overlap between general cognitive ability and risk for schizophrenia: a report from the Cognitive Genomics consorTium (COGENT). Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:168–74.

McGrath JJ, Féron FP, Burne THJ, Mackay-Sim A, Eyles DW. The neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia: a review of recent developments. Ann Med. 2003;35:86–93.

Murray RM, Bhavsar V, Tripoli G, Howes O. 30 Years on: how the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia morphed into the developmental risk factor model of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43:1190–6.

Fusar-Poli P, Deste G, Smieskova R, Barlati S, Yung AR, Howes O, et al. Cognitive functioning in prodromal psychosis: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:562–71.

Liu Y, Wang G, Jin H, Lyu H, Liu Y, Guo W, et al. Cognitive deficits in subjects at risk for psychosis, first-episode and chronic schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry Res. 2019;274:235–42.

Tor J, Dolz M, Sintes-Estevez A, de la Serna E, Puig O, Munoz-Samons D, et al. Neuropsychological profile of children and adolescents with psychosis risk syndrome: the CAPRIS study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29:1311–24.

Bora E, Murray RM. Meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in ultra-high risk to psychosis and first-episode psychosis: do the cognitive deficits progress over, or after, the onset of psychosis?. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:744–55.

Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC. The genetics of cognition in schizophrenia. Genomic Psychiatry. 2024;1:28–35.

Karcher NR, Loewy RL, Savill M, Avenevoli S, Huber RS, Simon TJ, et al. Replication of associations with psychotic-like experiences in middle childhood from the adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) study. Schizophr Bull Open. 2020;1:sgaa009.

Karcher NR, Paul SE, Johnson EC, Hatoum AS, Baranger DAA, Agrawal A, et al. Psychotic-like experiences and polygenic liability in the adolescent brain cognitive development study. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2022;7:45–55.

Park J, Lee E, Cho G, Hwang H, Kim B-G, Kim G, et al. Gene–environment pathways to cognitive intelligence and psychotic-like experiences in children. eLife. 2024;12:RP88117.

Bramon E, Pirinen M, Strange A, Lin K, Freeman C, Bellenguez C, et al. A genome-wide association analysis of a broad psychosis phenotype identifies three loci for further investigation. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75:386–97.

About the Study. https://abcdstudy.org/about/, Date Accessed: 06-Aug-2025

Wang B, Giannakopoulou O, Austin-Zimmerman I, Irizar H, Harju-Seppanen J, Zartaloudi E, et al. Adolescent verbal memory as a psychosis endophenotype: a genome-wide association study in an ancestrally diverse sample. Genes (Basel). 2022;13:106.

Uban KA, Horton MK, Jacobus J, Heyser C, Thompson WK, Tapert SF, et al. Biospecimens and the ABCD study: rationale, methods of collection, measurement and early data. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:97–106.

Gogarten SM, Sofer T, Chen H, Yu C, Brody JA, Thornton TA, et al. Genetic association testing using the GENESIS R/Bioconductor package. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:5346–8.

R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/, 2025, Date Accessed: 06-Aug-2025

Manichaikul A, Mychaleckyj JC, Rich SS, Daly K, Sale M, Chen WM. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2867–73.

Zheng X, Levine D, Shen J, Gogarten SM, Laurie C, Weir BS. A high-performance computing toolset for relatedness and principal component analysis of SNP data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3326–8.

Ruan Y, Lin Y-F, Feng Y-CA, Chen C-Y, Lam M, Guo Z, et al. Improving polygenic prediction in ancestrally diverse populations. Nat Genet. 2022;54:573–80.

Auton A, Abecasis GR, Altshuler DM, Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Bentley DR, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74.

Trubetskoy V, Pardinas AF, Qi T, Panagiotaropoulou G, Awasthi S, Bigdeli TB, et al. Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature. 2022;604:502–8.

Mullins N, Forstner AJ, O’Connell KS, Coombes B, Coleman JRI, Qiao Z, et al. Genome-wide association study of more than 40,000 bipolar disorder cases provides new insights into the underlying biology. Nat Genet. 2021;53:817–29.

Lee JJ, Wedow R, Okbay A, Kong E, Maghzian O, Zacher M, et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1112–21.

Savage JE, Jansen PR, Stringer S, Watanabe K, Bryois J, de Leeuw CA, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in 269,867 individuals identifies new genetic and functional links to intelligence. Nat Genet. 2018;50:912–9.

Wechsler D WAIS-R : Wechsler adult intelligence scale-revised. New York, N.Y.: Psychological Corporation; 1981. ©19811981.

Wechsler D Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (3rd ed.). 1997.

Rey A L’examen clinique en psychologie. [The clinical examination in psychology.]. Oxford, England: Presses Universitaries De France; 1958. pp. 222–222. pp.

Luciana M, Bjork JM, Nagel BJ, Barch DM, Gonzalez R, Nixon SJ, Banich MT. Adolescent neurocognitive development and impacts of substance use: Overview of the adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) baseline neurocognition battery. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:67–79.

Bracher-Smith M, Crawford K, Escott-Price V. Machine learning for genetic prediction of psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:70–79.

Breiman L. Random forests. Machine Learn. 2001;45:5–32.

Auchter AM, Hernandez Mejia M, Heyser CJ, Shilling PD, Jernigan TL, Brown SA, et al. A description of the ABCD organizational structure and communication framework. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:8–15.

Nakahara S, Medland S, Turner JA, Calhoun VD, Lim KO, Mueller BA, et al. Polygenic risk score, genome-wide association, and gene set analyses of cognitive domain deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;201:393–9.

Koch E, Nyberg L, Lundquist A, Pudas S, Adolfsson R, Kauppi K. Sex-specific effects of polygenic risk for schizophrenia on lifespan cognitive functioning in healthy individuals. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:520.

Mistry S, Harrison JR, Smith DJ, Escott-Price V, Zammit S. The use of polygenic risk scores to identify phenotypes associated with genetic risk of bipolar disorder and depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2018;234:148–55.

Strakowski SM, Fleck DE, DelBello MP, Adler CM, Shear PK, Kotwal R, Arndt S. Impulsivity across the course of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:285–97.

Reddy LF, Lee J, Davis MC, Altshuler L, Glahn DC, Miklowitz DJ, Green MF. Impulsivity and risk taking in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:456–63.

Ahn WY, Rass O, Fridberg DJ, Bishara AJ, Forsyth JK, Breier A, et al. Temporal discounting of rewards in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120:911–21.

Smith-Woolley E, Selzam S, Plomin R. Polygenic score for educational attainment captures DNA variants shared between personality traits and educational achievement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2019;117:1145–63.

Ujma PP, Eszlari N, Millinghoffer A, Bruncsics B, Torok D, Petschner P, et al. Genetic effects on educational attainment in Hungary. Brain Behav. 2022;12:e2430.

Karcher NR, Barch DM, Avenevoli S, Savill M, Huber RS, Simon TJ, et al. Assessment of the prodromal questionnaire-brief child version for measurement of self-reported psychoticlike experiences in childhood. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:853–61.

Karcher NR, Perino MT, Barch DM. An item response theory analysis of the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief Child Version: developing a screening form that informs understanding of self-reported psychotic-like experiences in childhood. J Abnorm Psychol. 2020;129:293–304.

Schimmelmann BG, Walger P, Schultze-Lutter F. The significance of at-risk symptoms for psychosis in children and adolescents. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:32–40.

Ayesa-Arriola R, de la Foz VO, Murillo-Garcia N, Vazquez-Bourgon J, Juncal-Ruiz M, Gomez-Revuelta M, et al. Cognitive reserve as a moderator of outcomes in five clusters of first episode psychosis patients: a 10-year follow-up study of the PAFIP cohort. Psychol Med. 2023;53:1891–905.

Hess JL, Tylee DS, Mattheisen M, Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C, Lundbeck Foundation Initiative for Integrative Psychiatric R, Borglum AD, et al. A polygenic resilience score moderates the genetic risk for schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:800–15.

Hess JL, Barnett EJ, Hou J, Faraone SV, Glatt SJ. Polygenic Resilience Scores are Associated With Lower Penetrance of Schizophrenia Risk Genes, Protection Against Psychiatric and Medical Disorders, and Enhanced Mental Well-Being and Cognition. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2025.

Duncan L, Shen H, Gelaye B, Meijsen J, Ressler K, Feldman M, et al. Analysis of polygenic risk score usage and performance in diverse human populations. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3328.

Human Pangenome Reference Consortium. https://humanpangenome.org/index.html, Date Accessed: 06-Aug-2025

Polygenic RIsk MEthods in Diverse populations (PRIMED) Consortium. https://www.genome.gov/Funded-Programs-Projects/PRIMED-Consortium, 2024, Date Accessed: 06-Aug-2025

Ge T, Chen CY, Ni Y, Feng YA, Smoller JW. Polygenic prediction via Bayesian regression and continuous shrinkage priors. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1776.

Ge T, Irvin MR, Patki A, Srinivasasainagendra V, Lin Y-F, Tiwari HK, et al. Development and validation of a trans-ancestry polygenic risk score for type 2 diabetes in diverse populations. Genome Med. 2022;14:70.

Thygesen JH, Presman A, Harju-Seppanen J, Irizar H, Jones R, Kuchenbaecker K, et al. Genetic copy number variants, cognition and psychosis: a meta-analysis and a family study. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:5307–19.

Hubbard L, Rees E, Morris DW, Lynham AJ, Richards AL, Pardinas AF, et al. Rare copy number variants are associated with poorer cognition in Schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;90:28–34.

Young AI. Discovering missing heritability in whole-genome sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2022;54:224–6.

Allott K, Liu P, Proffitt TM, Killackey E. Cognition at illness onset as a predictor of later functional outcome in early psychosis: systematic review and methodological critique. Schizophr Res. 2011;125:221–35.

Song J, Yao S, Kowalec K, Lu Y, Sariaslan A, Szatkiewicz JP, et al. The impact of educational attainment, intelligence and intellectual disability on schizophrenia: a Swedish population-based register and genetic study. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:2439–47.

Martin AR, Kanai M, Kamatani Y, Okada Y, Neale BM, Daly MJ. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nat Genet. 2019;51:584–91.

Palk AC, Dalvie S, de Vries J, Martin AR, Stein DJ. Potential use of clinical polygenic risk scores in psychiatry - ethical implications and communicating high polygenic risk. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2019;14:4.

Haworth CM, Wright MJ, Luciano M, Martin NG, de Geus EJ, van Beijsterveldt CE, et al. The heritability of general cognitive ability increases linearly from childhood to young adulthood. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:1112–20.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants, clinical teams, and research personnel involved in PEIC, GROUP, and the ABCD Study.

Funding

The Santander cohort was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI020499, PI050427, PI060507), SENY Fundació (CI 2005-0308007), Fundacion Ramón Areces and Fundacion Marqués de Valdecilla (API07/011, API10/13). Grant ISCIII: ICI21_00089 and PI22_01379. Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive DevelopmentSM (ABCD) Study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the NIMH Data Archive (NDA). This is a multisite, longitudinal study designed to recruit more than 10,000 children age 9–10 and follow them over 10 years into early adulthood. The ABCD Study® is supported by the National Institutes of Health and additional federal partners under award numbers U01DA041048, U01DA050989, U01DA051016, U01DA041022, U01DA051018, U01DA051037, U01DA050987, U01DA041174, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041028, U01DA041134, U01DA050988, U01DA051039, U01DA041156, U01DA041025, U01DA041120, U01DA051038, U01DA041148, U01DA041093, U01DA041089, U24DA041123, U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners.html. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/consortium_members/. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in the analysis or writing of this report. This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the NIH or ABCD consortium investigators. The ABCD data repository grows and changes over time. The ABCD data used in this report came from doi:10.15154/kwr5-qf75. DOIs can be found at https://nda.nih.gov/abcd (accessed on 01 August 2025). This study is funded by the following grants and fellowships: Medical Research Council (G1100583, MR/W020238/1, MR/Z504816/1). National Institute of Health Research (NIHR200756). Mental Health Research UK (John Grace QC Scholarship 2018). Economic Social Research Council’s Co-funded doctoral award (ES/P000592/1). The British Medical Association’s Margaret Temple Fellowship. Medical Research Council New Investigator and Centenary Awards (G0901310, G1100583). NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and University College London (BRC1114/MH). K.J.’s work was undertaken as part of the UCL-Birkbeck MRC-DTP PhD program, generously funded by the Medical Research Council (MR/W006774/1). A.R.B. is funded by the Wellcome Trust through a PhD Fellowship in Mental Health Science (218497/Z/19/Z). N.S.K. is supported by a studentship co-funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and Mental Health Research UK (ES/P000592/1). D.P. received the FCT 2022.00586.CEECIND fellowship (DOI: 10.54499/2022.00586.CEECIND/CP1722/CT0011). All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization: LV, KJ, BW, EB; data curation: BW; formal analysis: LV, KJ; funding acquisition: EB; investigation: AM, JHT, BZA, SB, BCF, JH, CI, EK, SML, IM, CM, RMM, DP, TT, NEMH, EB; methodology: LV, KJ, BW, EB; project administration: EB; resources: BZA, SB, BCF, JH, CI, EK, SML, IM, CM, RMM, DP, TT, NEMH, EB; software: LV, KJ, BW; supervision: BW, SM, AM, JHT, EB; visualization: LV, KJ; writing – original draft: LV, KJ; writing – review & editing: BW, SM, MC, ARB, NSK, RL, RA, AM, JHT, BZA, SB, BCF, JH, CI, EK, SML, IM, CM, RMM, DP, TT, NEMH, EB.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.B. has received financial support for symposia from Medice, Takeda and is on the advisory board for AGB-Pharma. All other authors report no disclosures.

Ethics statement

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Varney, L., Jedlovszky, K., Wang, B. et al. Effect of polygenic scores on the relationship between psychosis and cognition. Transl Psychiatry 15, 491 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03666-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03666-z