Abstract

Cross-sectional evidence suggested that frailty was an important risk factor for cognitive impairment. However, previous studies only focused on baseline frailty status, not taking into consideration the dynamic changes in frailty status during follow-up. This study aimed to investigate the associations between changes in frailty status and cognitive impairment. This study used data from three prospective cohorts: China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). Frailty status was evaluated by the frailty index and classified as robust, pre-frailty, or frailty. Cognitive function was assessed by memory, orientation and executive function. Linear mixed regression model was used to evaluate the longitudinal relationship between frailty statuses with cognitive impairment. A total of 49,864 participants with a mean of 2.70 follow-up times were included in the analysis. The median follow-up periods were 2.89 years in the CHARLS, 3.32 years in the ELSA, and 8.40 years in the HRS. Compared with robust participants, both pre-frailty and frailty were significantly associated with declined global cognitive function (beta −0.11, 95% CI: [−0.12, −0.09] for pre-frailty and beta −0.29 [95% CI: −0.30, −0.27] for frailty). Significant associations were also observed for memory (beta −0.27, 95% CI: [−0.29, −0.26] for frailty), orientation (beta −0.15 [95% CI: −0.17, −0.13] for frailty), and executive function (beta −0.21 [95% CI: −0.23, −0.19] for frailty). The subgroup analysis revealed that the CHARLS cohort had the greatest effect, and it was the main source of heterogeneity. Pre-frailty and frailty are associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment, highlighting the need for early assessment and monitoring of frailty in at-risk populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With the global population steadily aging, frailty, a prevalent geriatric syndrome, is becoming a major public health issue [1,2,3]. Frailty is marked by a decline in multiple physiological systems, which leads to heightened vulnerability to stressors [4,5,6,7]. It is well-established that frailty elevated the risk of several adverse health outcomes, including disability, falls, fractures, reduced quality of life, hospitalization, and even mortality [8,9,10,11]. In recent years, frailty has garnered significant attention in the area of cognitive health, as the incidence and prevalence of cognitive impairment also rise with age. Understanding the link between frailty and cognitive function could offer valuable insights for preventing and managing cognitive impairment in older adults.

Previous researches, which mainly consisted of cross-sectional and limited cohort studies, have shown that frailty are linked to a higher risk of cognitive impairment [12,13,14,15]. However, these studies primarily focused on frailty status at a single time point, without accounting for how frailty status may change over time. Unlike a one-time assessment, tracking frailty status dynamically over a period can provide a more comprehensive view of its biological connections, including how frailty progression may relate to cognitive decline. Importantly, growing evidence suggests that frailty can be reversed with appropriate interventions, making it crucial to explore how shifts in frailty status over time are associated with cognitive impairment.

In the current study, we utilized data from three large prospective cohorts: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), and the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Our objective was to examine the longitudinal relationship between frailty status and cognitive function over time.

Methods

Data source and participants

All the information we used in this study were derived from prospective and nationally representative cohort studies conducted by the CHARLS, the HRS and the ELSA [16,17,18]. The 3 cohorts were approved by the Peking University Institutional Review Board, the University of Michigan Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board, and the London Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee, respectively, and informed consent was obtained from each participant.

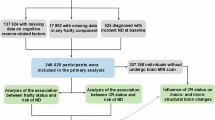

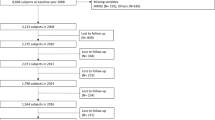

This study used data from wave 1 to wave 3 (2011–2015) of CHARLS, wave 9 to wave 15 (2008–2020) of HRS, wave 7 to wave 9 (2014/2015–2018/2019) of ELSA. The initial survey of each participant was regarded as the baseline for this study. The inclusion criteria as follows: (1) Complete information on frailty and cognitive function should be provided; (2) Aged ≥ 45 years; (3) Have not been diagnosed with memory related diseases such as dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. Figure 1 shows the selection process of the participants.

Assessment of frailty

Frailty was assessed using a frailty index (FI), which quantifies the accumulation of various age-related health deficits [19]. In this study, we developed the FI by adhering to the established methodology described in prior research [6, 7, 20]. Using data from CHARLS, ELSA, and HRS, we selected 28 items to construct the FI, which encompassed aspects such as diseases (excluding heart disease and stroke), symptoms, disabilities, physical functioning, and depression (details were provided in Additional file: Table S1). Each item was categorized as binary variables, with 1 indicating the presence of a deficit and 0 indicating its absence, based on respective cut-off values. The FI for each participant was calculated by dividing the sum of the health deficits by 28, producing a continuous variable with values between 0 and 1, where higher FI scores represented greater frailty. As recommended by previous studies [2], frailty is divided into three groups: robust (FI ≤ 0.10), pre-frail (0.10 < FI < 0.25) and frail (FI ≥ 0.25).

Cognitive assessment

Cognitive function was assessed by memory, orientation and executive function. Memory test was immediate and delayed recall of 10 unrelated words, with 1 point awarded for each word recalled. The range of memory test was 0–20, with higher scores indicating better memory performance. Orientation was assessed by 4 questions on the year, the month, the date of the month, and the day of the week, 1 point for each correct answer, with a range of 0–4. Executive function was assessed by the Serial Seven test (0–5 points) and an intersecting pentagon copying test (0 or 2 points) in the CHARLS (0–7 points in total), and the counting-backward test (0–2 points) and the Serial Seven test (0–5 points) in both of the HRS and the ELSA (0–7 points in total). The Serial Sevens test required participants to decrease 7 from 100 in a row for five times, with 1 point awarded for each correct answer. The intersecting pentagon copying test required participants to observe and draw a picture of two overlapping pentagon, 2 points for a successful drawing. The counting-backward test required participants count backwards from 20 as quickly as they could, 2 points for success. The global cognitive function score was the sum of the component scores (0–31 points), with higher scores indicating better cognitive function.

Standardized baseline z-scores were computed for test scores within each domain and global cognitive function by subtracting the mean baseline scores and dividing by the corresponding standard deviation (SD). The z-score of 1 indicates cognitive performance scores 1 SD above the mean baseline.

Covariates

The covariates included age (years), sex (male or female), education, marital status, smoking status, drinking status, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) and time (years since baseline). To ensure consistency across the data from the three databases, marital status was categorized into two groups: married or partnered, and other marital statuses (including separated, divorced, unmarried, or widowed). Education level was stratified into three categories: below high school, high school, and above college. Smoking status was classified as never smokers and former smokers. Current smokers were defined as individuals who currently smoke. Similarly, drinking status was categorized as never drinkers and former drinkers.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive analysis, continuous variables were presented as the mean [standard deviation (SD)] or the median [interquartile range (IQR)], depending on distribution. Categorical variables were reported as counts (percentages).

The linear mixed regression model was used to evaluate the relationship between frailty and cognitive z-scores (both global and domain). A person-level random intercept was used to account for the effects of repeated measurements of both frailty and cognitive function. The following three models were used to control for potential effects of the aforementioned covariates: Model 1 did not adjust anything; Model 2 was adjusted or demographic factors (age, sex, education and marital status); Model 3 was further adjusted for lifestyle factors (smoking status, drinking status), BMI and time (years since baseline). Subgroup analysis divided participants into CHARLS, HRS, and ELSA groups based on their origin, calculated the effects of frailty on domain and global cognitive function, respectively, and performed a random-effects meta-analysis for synthesis. Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistics were used to evaluate the heterogeneity of β values between the two groups.

We also conducted the following sensitivity analyses: First, we excluded participants who had been followed up less than 3 times. Second, we excluded participants who aged <60 years. Third we performed sensitivity analyses separately according to participant sex. Forth, we performed the analysis using raw cognitive scores rather than z-scores.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software 4.3.1 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). Two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 49,864 participants (15,242 from the CHARLS; 24,386 from the HRS and 10,236 from the ELSA) were included in this study, with a mean age of 62.06 ± 10.78 years, and 26,679 (53.30%) of them were females. Among all participants, 8903 (17.85%) met the criteria for frail, 16,141 (32.37%) for pre-frailty, and 24,820 (49.78%) for robust. Baseline characteristics of these participants are presented in Table 1. The number of follow-up times ranged from 1–7 with a mean value of 2.70. The median follow-up periods were 2.89, 3.32, and 8.40 years for the CHARLS, ELSA, and HRS, respectively.

Association of frailty and cognitive function

Table 2 and Fig. 2 show the association of frailty status with cognitive function. After adjusting for confounders, we observed that both pre-frailty and frailty were independently and significantly associated with declined global and domain cognitive function. In compared with participants with robust, the beta of global cognitive function z-scores of those with pre-frailty and frailty were −0.11 (95% CI: −0.12, −0.09) and −0.29 (95% CI: −0.30, −0.27), respectively (P for trend < 0.0001). Similarly, compared to those without frailty, patients with pre-frailty and frailty had declined z-scores of memory (beta −0.11, 95% CI: [−0.12, −0.09] for pre-frailty and beta −0.27 95% CI: [−0.29, −0.26] for frailty), orientation (beta −0.06, 95% CI: [−0.07, −0.05] for pre-frailty and beta −0.15 95% CI: [−0.17, −0.13] for frailty), and executive function (beta −0.08, 95% CI: [−0.09, −0.07] for pre-frailty and beta −0.21 95% CI: [−0.23, −0.19] for frailty).

The solid line represents the adjusted mean difference in cognitive change in global cognition (a), memory (b), orientation (c), and executive function (d) after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, education, cohabitation status, current smoking, alcohol consumption and time. Shadows represent 95% CI. The detailed results are presented in Table 2.

Subgroup analysis

As shown in Table 3 and Fig. 3, the separate analysis in each of the 3 cohorts showed that the effect size in the CHARLS cohort was the largest for both domain and global cognitive function. The meta-analysis showed that in frailty group the aggregated results were similar to the main results in terms of memory, orientation, executive function and global cognitive function, but the results in the orientation domain of the pre-frailty group changed to non-significant. Significant heterogeneity characterized the associations across the CHARLS, HRS, and ELSA cohorts, except for the consistent effect of pre-frailty on memory. Sensitivity analysis showed that the source of heterogeneity was mainly the CHARLS cohort (Additional file: Table S2, Table S3).

Sensitivity analysis

In sensitivity analyses, the effects of pre-frailty on global and domain cognitive function were consistent with the trend of the main findings. When restricting the analysis to participants with ≥3 follow-up assessments, the association between frailty and cognitive decline (both global and domain-specific) weakened (beta −0.23 95% CI: [−0.25, −0.22] for global cognitive function, −0.24 95% CI: [−0.26, −0.22] for memory, −0.08 95%CI: [−0.09, −0.06] for orientation and −0.15 95% CI: [−0.18, −0.14] for executive function). In participants aged ≥60 years, the association between frailty and global cognitive and memory decline strengthened (beta −0.36 95%CI: [−0.37, −0.34] for global cognitive function and −0.37 95%CI: [−0.39, −0.35] for memory). Separate analyses stratified by participant sex yielded results closely aligned with the primary analysis. Analyses using raw cognitive scores instead of z-scores yielded results consistent with the overall trend observed in the primary analysis. (Additional file: Table S4, Table S5).

Discussion

In this study with three prospective cohorts, we examined the longitudinal associations of frailty status with cognitive function in older adults. We found that physical frailty was associated with declined global cognitive function. Compared with participants without frailty, those with pre-frailty and frailty had a significantly accelerated decline of 0.11 SD/year and 0.29 SD/year in global cognitive z-score, respectively. The adverse effects were consistent across different cognitive domains, further strengthening the robustness of our findings.

Current literature on frailty status and cognitive function is relatively sparse. A cross-sectional study conducted in United States, with a sample size of 451 Mid-Life and older adults suggested that frailty phenotype was negatively correlated with all cognitive domains and remained constant across different age groups [10]. A meta-analysis of 38 cross-sectional studies in 2022 showed that frailty status has an overall significant negative impact on cognitive function in older adults [21]. Although it has been widely recognised that frailty is associated with cognitive impairment based on cross-sectional studies, limited studies have evaluated the longitudinal relationships. A recent large-scale longitudinal study of 29,849 older adults across US and UK cohorts revealed accelerated frailty accumulation 4–9 years preceding dementia onset and established frailty as a robust independent risk factor for dementia [22]. Similarly, a smaller cohort study (n = 761) reported frailty-associated cognitive decline [14]. However, both studies assessed the predictive value of baseline frailty status without considering dynamic transitions in frailty during follow-up. A recent meta-analysis found that 42.8% of 42,775 community-dwelling older participants changed their frailty status (13.7% improved, 29.1% worsened) during a mean follow-up of 3.9 years [23]. Our study demonstrated that even consider the dynamic change of frailty status, frail individual was still associated with increased risk of cognitive decline. Our findings further supported the viewpoint of frailty as an independent risk factor for cognitive decline.

The evidence on the effects of frailty on cognitive function in specific domains are inconsistent. A recent study based on 83 community-dwelling older adults demonstrated that frailty was negatively correlation with executive functions and processing speed, while showing no significant association with global cognitive function, verbal reasoning, working memory, or episodic memory [24]. The Brazilian FIBRA study found that frailty significantly impacted several cognitive functions, including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), orientation, command execution, immediate memory, verbal fluency, and clock-drawing abilities, but had no effect on delayed memory [25]. Another analysis from the same cohort further indicated that frailty negatively influenced time orientation, immediate memory, naming, repetition, reading, and overall MMSE performance. However, it did not significantly affect spatial orientation, delayed memory, attention/calculation, command following, writing, or constructional praxis [26]. In this study, the orientation domain was less vulnerable to the effects of frailty compared to other cognitive functions. These inconsistencies arise from the multidimensional nature of frailty, the neural heterogeneity across cognitive domains, methodological variations between studies, and the inherent diversity of study populations. The contradictory findings underscore the complexity of aging. The relationship between frailty and cognition is neither simple nor linear; rather, it represents a dynamic, multifactorial interplay. This complexity necessitates further investigation.

In subgroup analyses, the CHARLS cohort was the main source of heterogeneity, being the largest for both domain-specific and global cognitive assessments. The HRS and ELSA cohorts showed similar patterns in global, memory, and executive function domains but diverged significantly in the orientation domain. Distinct genetic profiles, lifestyles, and cultural traditions exist across racial and ethnic groups. While the CHARLS cohort primarily represents the Chinese population, the HRS and ELSA cohorts largely comprise European and American participants. These differences may introduce heterogeneity in cognitive outcomes: Genetic factors can influence brain structure and function, while cultural traditions and lifestyle elements, including dietary habits, educational attainment and social engagement, may independently impact cognitive abilities. Notably, CHARLS had lower educational attainment than HRS and ELSA. Higher educational attainment is associated with enhanced cognitive reserve, potentially conferring greater resilience to cognitive decline. Consequently, educational disparities between cohorts may contribute to heterogeneity in cognitive assessments.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the link between frailty to cognitive decline. First, vascular disease is increasingly recognized as a contributor to cognitive decline in older adults, with reduced blood flow and impaired vascular function potentially mediating or sharing common pathways with both frailty and cognitive decline [27,28,29]. Second, changes in the immune system and inflammation are closely associated with frailty [30, 31], and the role of inflammation in cognitive impairment is well-documented [32]. This suggests that inflammatory processes contribute to the development of both conditions. Future research should explore the mechanisms linking frailty with cognitive decline and assess potential interventions to address these issues.

This study has several notable strengths. First, it leveraged three large, nationally representative cohort studies from China, the United States, and the United Kingdom, all of which were rigorously designed with substantial sample sizes and strong representativeness. The robustness of the findings was further confirmed through subgroup and sensitivity analyses. Second, the consistency of results across all three cohorts enhances the generalizability of the findings. Third, the repeated measurement of frailty and cognitive function over time enabled the study to account for the dynamic changes in both frailty and cognitive function during follow-up. However, there are some limitations should also be noted. First, the inherent constraints of observational studies limit the ability to establish causality. Although the study demonstrated an association between frailty and global cognitive function, as well as various cognitive domains, the possibility of reverse causality cannot be entirely ruled out. Further research is needed to explore the relationship between frailty and cognitive function, along with the underlying biological mechanisms. Second, the frailty index in this study was constructed with 28 deficits, lower than that highlighted by classic frailty theory, and ideally the index should include at least 30–40 deficits, potentially underestimating frailty prevalence or weakening associations with cognitive function. Future work could address this issue by expanding the index. Third, despite adjusting for numerous potential confounders, residual confounding may still influence the results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this longitudinal analysis of 49,864 participants in three international cohorts showed that both pre-frailty and frailty were significantly associated with accelerated declines in global and domain cognitive function. Crucially, our study advances previous evidence by considering the dynamics of frailty status over time, reinforcing frailty as an independent predictor of cognitive decline. Future research should develop targeted interventions to monitor the trajectory of frailty and timely implement strategies to prevent cognitive impairment in older adults.

Data availability

Data supporting the results of this study are available from official websites of China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (http:// charls.pku.edu.cn), English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (https:// ukdataservice.ac.uk), and Health and Retirement Study (https://hrs.isr.umich.edu).

References

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752–62.

Gómez-Gómez ME, Zapico SC. Frailty, cognitive decline, neurodegenerative diseases and nutrition interventions. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2842.

He D, Wang Z, Li J, Yu K, He Y, He X, et al. Changes in frailty and incident cardiovascular disease in three prospective cohorts. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:1058–68.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–156.

Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, Kowal P, Onder G, Fried LP. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet. 2019;394:1365–75.

Hu W, Chu J, Zhu Y, Chen X, Sun N, Han Q, et al. The longitudinal association between frailty, cognition, and quality of life in older Europeans. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2023;78:809–18.

Sang N, Liu RC, Zhang MH, Lu ZX, Wu ZG, Zhang MY, et al. Changes in frailty and depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older Chinese people: a nationwide cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:301.

Veronese N, Custodero C, Cella A, Demurtas J, Zora S, Maggi S, et al. Prevalence of multidimensional frailty and pre-frailty in older people in different settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;72:101498.

Nari F, Jang BN, Youn HM, Jeong W, Jang SI, Park EC. Frailty transitions and cognitive function among South Korean older adults. Sci Rep. 2021;11:10658.

Goodman ZT, Banerjee N, Rooks J, McInerney K, Sun X, Getz S, et al. Measuring the frailty phenotype and its association with cognition in mid-life and older age. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;89:415–26.

Ma W, Wu B, Gao X, Zhong R. Association between frailty and cognitive function in older Chinese people: a moderated mediation of social relationships and depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2022;316:223–32.

Aarsland D, Creese B, Politis M, Chaudhuri KR, Ffytche DH, Weintraub D, et al. Cognitive decline in parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:217–31.

Rabin LA, Smart CM, Amariglio RE. Subjective cognitive decline in preclinical alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2017;13:369–96.

Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. Physical frailty is associated with incident mild cognitive impairment in community-based older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:248–55.

McAdams-DeMarco MA, Tan J, Salter ML, Gross A, Meoni LA, Jaar BG, et al. Frailty and cognitive function in incident hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:2181–9.

Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:61–8.

Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JW, Weir DR. Cohort profile: the health and retirement study (HRS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:576–85.

Steptoe A, Breeze E, Banks J, Nazroo J. Cohort profile: the english longitudinal study of ageing. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1640–8.

Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:24.

He D, Qiu Y, Yan M, Zhou T, Cheng Z, Li J, et al. Associations of metabolic heterogeneity of obesity with frailty progression: results from two prospective cohorts. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2023;14:632–41.

Robinson TL, Gogniat MA, Miller LS. Frailty and cognitive function in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Neuropsychol Rev. 2022;32:274–93.

Ward DD, Flint JP, Littlejohns TJ, Foote IF, Canevelli M, Wallace LMK, et al. Frailty trajectories preceding dementia in the US and UK. JAMA Neurol. 2025;82:61–71.

Kojima G, Taniguchi Y, Iliffe S, Jivraj S, Walters K. Transitions between frailty states among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;50:81–8.

Langlois F, Vu TT, Kergoat MJ, Chassé K, Dupuis G, Bherer L. The multiple dimensions of frailty: physical capacity, cognition, and quality of life. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:1429–36.

Yassuda MS, Lopes A, Cachioni M, Falcao DV, Batistoni SS, Guimaraes VV, et al. Frailty criteria and cognitive performance are related: data from the FIBRA study in Ermelino Matarazzo, São Paulo, Brazil. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16:55–61.

Macuco CR, Batistoni SS, Lopes A, Cachioni M, da Silva Falcão DV, Neri AL, et al. Mini-Mental State Examination performance in frail, pre-frail, and non-frail community dwelling older adults in Ermelino Matarazzo, São Paulo, Brazil. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:1725–31.

Halil M, Cemal Kizilarslanoglu M, Emin Kuyumcu M, Yesil Y, Cruz Jentoft AJ. Cognitive aspects of frailty: mechanisms behind the link between frailty and cognitive impairment. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:276–83.

de la Torre JC. Vascular risk factor detection and control may prevent alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;9:218–25.

Aguilar-Navarro SG, Mimenza-Alvarado AJ, Anaya-Escamilla A. Gutiérrez-robledo LM: frailty and vascular cognitive impairment: mechanisms behind the link. Rev Invest Clin. 2016;68:25–32.

Collerton J, Martin-Ruiz C, Davies K, Hilkens CM, Isaacs J, Kolenda C, et al. Frailty and the role of inflammation, immunosenescence and cellular ageing in the very old: cross-sectional findings from the newcastle 85+ study. Mech Ageing Dev. 2012;133:456–66.

Soysal P, Stubbs B, Lucato P, Luchini C, Solmi M, Peluso R, et al. inflammation and frailty in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;31:1–8.

Jefferson AL, Massaro JM, Wolf PA, Seshadri S, Au R, Vasan RS, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers are associated with total brain volume: the framingham heart study. Neurology. 2007;68:1032–8.

Acknowledgements

All authors thank the original data collectors, depositors, copyright holders, and funders of China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, and Health and Retirement Study.

Funding

This work was supported by Major Projects of Collaborative Innovation of Zhengzhou No.18XTZX12009, Special Major Public Welfare Project of Henan Province No. 201300310800, Key project of Science and Technology of Henan Province No.222102310418 and the key R & D program of Henan province (251111314800).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HL and ZY carried out the concept and design. ZL, YX, JW, XW, HZ, JZ, JH, YT implemented the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. XZ, YB drafted the manuscript. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content was conducted by all authors. XZ, YB performed the statistical analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Peking University. The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of London Multi-Centre Research. The Health and Retirement Study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the University of Michigan. Informed consent was obtained from each subject in these three cohorts.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Bo, Y., Li, Z. et al. Association between frailty and cognitive function: a pooled analysis of three ageing cohorts. Transl Psychiatry 15, 486 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03674-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03674-z