Abstract

Cumulative stress is known for its detrimental effects, including anxiety and stress-related disorders. However, the potential positive or ‘hormetic’ outcomes of chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) remain vague. In our study using adult male Wistar rats subjected to a 14-day CUS model, we explored the implications of its cumulative effects. We focused on how CUS influenced anxiety-like behavior, extinction memory, and the expression of specific receptors in the dorsal hippocampus (dHP). Our results indicated that CUS led to increased anxiety-related behaviors and heightened basal corticosterone levels. Interestingly, while aversive memory retrieval in CUS rats showed increased freezing, they exhibited enhanced memory extinction. This result suggests a compensatory mechanism initiated by CUS, allowing the rats to overcome the adverse effects of heightened freezing during memory recall. Moreover, during the extinction phase, there were notable changes in receptor expressions and neuronal activation in the dHP. Specifically, there was an increase in glucocorticoid receptor expression and a decrease in glutamate and adrenergic receptor expression levels. This altered receptor profile was linked to an overall rise in neuronal activity, albeit not immediate but cumulative. In summary, our findings indicate that while CUS amplifies anxiety-like behaviors, it paradoxically enhances specific cognitive processes. The altered receptor expression patterns in the dHP and increased neuronal activity suggest that CUS might provide individuals with improved coping mechanisms against recurring stressful situations, revealing stress responses’ complex and sometimes beneficial nature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

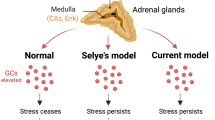

Stress plays a crucial evolutionary role in modulating aversive memory acquisition, retrieval, and extinction mechanisms. However, in the last decades, mental disorders have become the most incapacitating cause worldwide, mainly related to elevated, long-lasting daily stress exposure [1]. Once the organism acquires and retrieves the aversive memory, it can anticipate future challenges and display appropriate behavioral coping strategies [2]. Stressful stimuli promote acute and chronic physiological responses, directly influencing adaptation or allostatic processes depending on the duration of stress [3]. This response recruits specific brain structures such as the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN), septal-hippocampal complex, amygdaloid nuclei, and prefrontal cortex, activating the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, culminating with glucocorticoid (GC) release [4, 5], mainly corticosterone (CORT) in rodents. Classically, GCs bind to mineralocorticoid (MR) and/or glucocorticoid (GR) receptors and the ligand-receptor complexes (GC–GR) translocate to the nucleus, acting as transcription factors, modulating gene transcription at the glucocorticoid response elements (GRE) [6,7,8].

Previous studies have shown that the adaptive role of GCs is intimately related to anxiety-like behavior development, environmental perception and exploration, arousal, and the establishment of long-term memories related to aversive occasions [3, 9,10,11]. Concerning aversive memory formation, the hippocampus (HP) is a crucial region for GC–GR stress signaling, an adaptive phenomenon constantly modulated in a neuroendocrine manner [12,13,14]. Additionally, the dorsal HP (dHP) is responsible for contextual differential processing once the same engrams activated during aversive conditioning are reactivated during aversive memory retrieval [15, 16]. The dHP also assigns valence to memories, distinguishing different stimuli as aversive or not, being more recruited in response to negative situations such as aversive conditioning, and switching memory valence, which is essential for more adaptive stress responses [17, 18]. These roles reinforce the importance of GC–GRs and dHP in aversive memory studies. Furthermore, evidence highlights that AMPA glutamatergic receptor and noradrenergic signaling within the dHP are essential for regulating the aversive memory extinction processes [19,20,21].

Chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) is an efficient model for producing cellular and molecular alterations accompanied by behavioral outcomes. It consists of random exposure to various stressors [22], better mimicking the recurrence of the daily stresses in contemporary human life. Previous studies show that CUS leads to HPA axis hyperactivity via suppression of auto-feedback mechanisms and alters GR expression in the central amygdala (CeA), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BST), lateral septal nucleus, and the PVN [4, 23]. However, the role of GCs and how the hippocampal MR and GR signaling interfere with and impair adaptive anxiety and memory behaviors are poorly understood. Therefore, this study evaluated the CUS effects on HPA axis autoregulation, anxiety-like behavior, contextual aversive memory acquisition and extinction, and physiological and biochemical modifications. We also investigated the relationship of these changes with GR and MR and the involvement of glutamate and noradrenaline signaling, particularly in the dHP.

Materials and methods

Animals

Ninety adult male Wistar rats (60 days old) from the SPF Rat Production Unit of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences (ICB) Animal Facility Network at the University of São Paulo (USP) were used. They were housed at the Pharmacology Department – Unity I – ICB Facility and acclimatized for at least 1 week before the beginning of the experiments. All protocols and procedures followed the ICB/USP Ethics Committee’s Animal Use standards (CEUA-ICB 80/2014) and the Brazilian National Council for the Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA) guidelines. Efforts were taken to minimize animal suffering and reduce the number of animals used to the minimum required for detecting statistically significant effects.

Experimental design

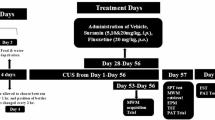

The experimental designs are depicted in Figs. 1A, 2A, 3A, and 4A. After one week of acclimatization in the vivarium, the animals were randomly allocated to the CUS group and stressed for 14 days, or the control group (CTR), which remained undisturbed in their cages during the CUS period. Blood was collected from the tail for corticosterone measurements at two moments: basal (24 hours before the first CUS session) and day 15 (24 hours after the final CUS session) (Fig. 1A). Twenty-four hours after the last stress session (day 15), randomly chosen animals were placed in the elevated plus-maze (EPM) and evaluated for anxiety-like behavior (Fig. 2A). Another portion of the rat sample was submitted to the paired or unpaired aversive memory extinction protocol (Figs. 3A and 4A). For these animals, tail blood was collected from paired animals to measure corticosterone concentrations at two time points: day 15 (24 hours after the final CUS session and 30-min after footshock during aversive conditioning protocol) and day 21 (six days after the last CUS session and immediately after termination of the extinction protocol) (Fig. 1A). All behavioral tests were conducted between 9 a.m. and 2 p.m. and recorded using a webcam (Logitech C920 HD Pro, Lausanne, Switzerland).

Schematic representation of the experimental design (A). The control group (CTR) is always represented in green tones, and the stressed group (CUS) in pink tones. CUS had less weight gain compared to CTR, as shown by the percentage of weight gain 24 h after the last CUS session (conditioning, day 15) and extinction test (day 21), both in paired (B and C) and unpaired animals (D and E). Twenty-four hours after CUS, the CORT concentration increased when compared to the basal period (before CUS) (F) or CTR group in pre-US (conditioning) (G). The CORT release of the CUS group during retrieval (day 16, 48 h after the last CUS session) was more significant than the CORT concentration during post-US conditioning (day 15) or extinction test (day 21), analyzed 30 min after tests (H). Results are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6–14 animals/group in B and C; n = 32 animals/group in E; n = 9–14 animals/group in F; n = 6–9 animals/group in G; n = 8–14 animals/group in H). In B and D, * (p < 0.05) vs CTR group. ** (p < 0.01) vs. CTR group in C and E. In F, *** (p < 0.001) vs. basal. In G, * (p < 0.05) vs CTR group. In H, * and ** (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01) vs. their respective group during retrieval.

Schematic representation of the experimental design (A). The control group (CTR) is always represented in green, and the stressed group (CUS) in pink. Representation of total exploratory activity in the EPM with CUS (right) exhibiting anxiety-like behavior by assessing and spending less time in open arms compared to CTR (left) (B). Percentage of open arm time: entire test (C) and minute-by-minute (C’). CUS performs more risk assessment behavior as represented on the total stretched-attend postures (SAP) occurrences (D) and its percentage minute-by-minute (D’) graphs. Percentage of open arms entries: entire test (E) and minute-by-minute (E’). Total rearing occurrences (F) and its percentage minute-by-minute (F’). No locomotor activity deficits were observed, as shown by the number of closed-arm entries: entire test (G) and minute-by-minute (G’). Number of total head-dipping occurrences (H) and percentage per minute (H’). The anxiety-like behavior due to CUS is evidenced by the anxiety index (score from 0–1, with 1 representing the maximum anxious state), which unites both open and closed arms time and entries data (I). Percentage of risk assessment occurring in protected areas (closed arm and central area): SAP (J), rearing (K), and head-dipping (L). Results are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 8–10 animals/group). Student’s t-test (C, D, E, F, G, H, I-L) and two-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test (C’, D’, E’, F’, G’, H’) were done. In C–E and I, * and ** (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively) vs. CTR group. In C’–E’ and H’, *, **, ***, **** (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001, respectively) CTR or CUS group during the fifth minute vs. their respective group during the first minute. # (p < 0.05) vs. their respective CTR group in C’ and D’.

Schematic representation of the experimental design (A). The control group (CTR) is always represented in green, and the stressed group (CUS) is depicted in pink. The entire learning curve (B) shows that CUS animals retrieve more of the aversive memory (B’) but extinguish it as CTR during the same time course (B”). CUS presents a lower extinction gain ratio (%) at the first extinction protocol day, which is already compensated from the second extinction day (C); moreover, CTR animals showed a higher extinction gain ratio during the extinction test (C’) similarly to the CUS group (C”). Results are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 14–24 animals/group in B, B’ and B”; n = 13–16 animals/group in C, C’ and C”). In B, **** (p < 0.0001) vs. their respective group in the retrieval test, # (p < 0.05) vs. CTR group, $ (p < 0.05) vs. their respective group in post-US. In B’, ** (p < 0.01) vs. CTR group. In C, **** (p < 0.0001) vs. their respective group in the retrieval test, # (p < 0.05) vs. CTR group. In C’, *** (p < 0.001) vs CTR group in first. In C”, *** (p < 0.001) vs CUS group in first.

Schematic representation of the experimental design (A). The control group (CTR) is always represented in green tones, and the stressed group (CUS) in pink tones. The unpaired protocol (B) demonstrates that the defensive response of unpaired CTR and CUS was context-dependent, as low freezing rates occurred in the neutral arena (NA); however, the unpaired CUS group showed higher freezing than the CTR group during the retrieval test (B’), extinction test (B”) and extinction sessions (B”’). Face to returning to the conditioning arena (CA) during the extinction test, unpaired CTR and CUS showed higher freezing, indicating that the extinction depends on successive re-exposures to the paired arena, although the time-lapse also had a negligible effect. CUS animals presented an increased freezing absence ratio (%) on the first extinction protocol day similar CTR group (C); moreover, CTR and CUS groups showed higher freezing absence ratio (%) during extinction test (C’ and C”). Results are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 5–6 animals/group in B, B’, B”, B”‘; n = 6–8 animals/group in C, C’, C”). In B, * (p < 0.05) vs. their respective group in the post-US period, and # (p < 0.05) vs. their respective group in the pre-US period. In B’, * (p < 0.05) vs. CTR group. In B”, ** (p < 0.01) vs. CTR group. In B”‘, #, ## and ### (p < 0.05, p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively) vs. their respective CTR group. In C, **** (p < 0.0001) vs. their respective group in first. In C’, *** (p < 0.001) vs. CTR group in first. In C”, **** (p < 0.0001) vs. CUS group in first.

Chronic unpredictable stress

The CUS group was kept under a 12-h light/dark cycle with free access to food (standard rat chow) and filtered water, except on specific protocol days. As described previously, the animals were subjected to different stressors for 14 days (SI Appendix, Table S1) [23].

Elevated plus-maze

The EPM test was conducted as described in [24]. Behavioral measurements were performed using the X-Plo-Rat software [25]. The parameters analyzed were spatiotemporal and risk assessments and exploratory activity (see SI Appendix, Extended Methods 1.1 and 1.2).

Contextual aversive conditioning and extinction

The 7-day contextual aversive conditioning and extinction protocol (Fig. 2A, and described in SI Appendix, Extended Methods 1.3) was described in [11, 21]. Briefly, two groups, paired and unpaired (memory protocol control), were further subdivided into four groups: paired CTR and CUS and unpaired CTR and CUS.

The percentage of freezing was used as a parameter for aversive memory expression. We considered freezing to be the animal’s immobility, including vibrissae and sniffing movements, except for respiration-related signs [26]. In addition, an extinction gain ratio percentage (performed in paired groups) or freezing absence ratio percentage (mathematically similar to extinction gain, having another name because it is performed in unpaired groups) analysis was performed (see SI Appendix, Extended Methods 1.4). After each exposure, the arenas were cleaned with 5% alcohol (v/v) to avoid olfactory cues.

Brain structure dissection

Ninety minutes after the retrieval and extinction memory test, the animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated by a guillotine (Insight, EB 271, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil). The brains were removed and immersed in a phosphate-saline buffer solution (137 mM NaCl, 2.68 mM KCl, 1.27 mM KH2PO4, 8.06 mM Na2HPO4). Next, the dHP was bilaterally dissected on ice, using a coronal matrix with 1-mm slice intervals (Zivic Laboratories Inc., Portersville, P.A., USA), frozen on liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

Western blot

As described in the SI Appendix, Extended Methods 2, and Table S2, protein expression and phosphorylated forms were analyzed by Western blot.

Plasma corticosterone dosage

Serum corticosterone was measured using an enzyme-linked immunoassay (Enzo Life Sciences®, UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Serum was obtained by centrifuging the tail and trunk blood at 3500 rpm for 15 min and transferring the supernatant to tubes. The serum samples were then diluted 1:30 in the assay buffer, and spectrophotometric readings were recorded at 405 nm using the Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Bio Tek, Winooski, VT, USA).

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as the mean ± SEM and were analyzed by GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0) with outliers removed by the ROUT method (Q = 1%). Data were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. For weight gain, EPM, and part of the memory protocols analysis, an unpaired Student’s t-test was performed. For corticosterone serum levels and behavioral analysis (blinded analyses), we used two-way mixed-effects ANOVA with stress (CTR or CUS) and days of the memory protocol as factors. Post-hoc Tukey’s or Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests were used to compare within and intergroup differences. Statistical results are summarized in Tables S3–7.

Results

CUS impairs weight gain and increases basal CORT concentration up to 24 hours after the last CUS session but does not change CORT during conditioning and extinction

We have previously shown that CUS induces physical and behavioral changes, such as adrenal gland hypertrophy, for up to 24 hours after stress [4] and increased CORT release. Here, we confirmed that CUS reduced body weight gain in both paired and unpaired animals compared to the CTR group. This decrease persisted throughout the extinction test (Fig. 1A–E). Next, we analyzed CUS’s impact on CORT concentration during the contextual aversive conditioning protocol. We confirmed that CUS persistently increased CORT up to 24 hours after the last CUS session when the stressed animals went to the EPM or contextual conditioning compared to the basal period (pre-CUS) (Fig. 1F) or the CTR group (during day 15, pre-US) (Fig. 1G). Nonetheless, CUS did not sensitize the HPA axis activation to a second stressful event (contextual conditioning) since, after CS, the rise in CORT concentration was similar between CUS and CTR animals. When analyzing CORT release on days 15, 16, and 21, the statistical tests revealed a significant effect of time but not stress for both the CTR and CUS groups. CORT release 48 hours after the last CUS session (post-CS, day 16) was higher than the CORT concentration during post-US conditioning (day 15) and the extinction test (post-CS, day 21) (Fig. 1H). The statistical analyses are detailed in the SI Appendix, Table S3). Therefore, we corroborate a previous study [4] reporting that stress decreased weight gain and increased CORT concentration without sensitizing the HPA axis in a second aversive challenge.

CUS promotes immediate anxiety-like behavior

CUS-evoked anxiety-like behavior was evaluated using the EPM 24 hours after the last stress session. Statistical tests revealed a significant stress effect on decreasing the percentage of open arms time (%OAT) (Fig. 2C) and percentage of open arm entries (%OAE) (Fig. 2E). In addition, no significant effect for the closed arm entries was observed, suggesting no stress-induced changes in locomotor activity (Fig. 2G). The anxiety index revealed a higher anxiety-like pattern for the CUS group (Fig. 2I) (statistical analyses are detailed in the SI Appendix, Table S4). Concerning total stretched-attend postures (SAPs), there was a CUS-induced increase in risk assessment (Fig. 2D) that was not detected in the protected SAPs (Fig. 2J). Although stressed animals maintain a similar risk assessment proportion in the protected area, they have a higher frequency in total SAP when compared to the CTR group. Furthermore, no changes in total rearing (Fig. 2F), protected rearing percentage (Fig. 2K), total head-dipping (Fig. 2H), or protected head-dipping percentage (Fig. 2L) were observed (statistical analyses are detailed in SI Appendix, Table S4). Concerning minute-by-minute exploratory analysis, statistical tests showed that stress significantly affects open arm activity over time. The CUS group showed an exploratory profile with a lower %OAT and closed arm entries that remained stable throughout the test (Fig. 2C’ and G’). However, they had a higher %OAE in the first two minutes of the test that abruptly decreased, unlike the CTR rats, which exhibited a progressive decrease in exploration over time (Fig. 2E’). For the risk assessment and exploratory activity, CUS induced stable and high expressions of the total SAP and rearing during the entire period in the EPM (Fig. 2D’ and 2F’). In contrast, the CTR exhibited a progressive decrease in exploration over time for total SAP and total head-dipping (Fig. 2D’ and 2H’) but a high and constant total rearing percentage (Fig. 2F’) (statistical analyses are summarized in SI Appendix Table S4). These results suggest that CUS induces greater emotional arousal and a decision-making strategy based on avoidance instead of a risk-exposure approach.

CUS induces hyperresponsiveness in memory retrieval tests without affecting extinction memory

As illustrated in Figs. 3A and 4A, paired and unpaired stressed rats were submitted to the contextual aversive conditioning and the extinction protocol to investigate the CUS-induced changes in aversive memory. Statistical tests revealed a significant stress effect on the percentage of freezing observed throughout the contextual aversive conditioning and the extinction protocol. The CUS and CTR groups displayed increased freezing after footshock (during the post-US period) and during the retrieval test. These findings suggest that both groups displayed defensive behavior and formed long-term memory. During the retrieval test, CUS animals exhibited higher freezing than the CTR group, suggesting higher stress-induced contextual responsiveness. This behavior did not reflect changes in extinction since, during the extinction test, CUS animals displayed a similar level of extinction as the CTR from the third extinction session, maintained until the extinction test (day 6) (Fig. 3B). Similar effects were observed when comparing freezing separately on the retrieval test or extinction test between the experimental groups (Fig. 3B’ and B”) (statistical analyses are detailed in SI Appendix, Table S5). Our findings suggest that CUS heightened contextual responsiveness specifically increases freezing during the retrieval test while not affecting aversive memory acquisition or extinction.

Regarding the unpaired groups, the statistical test demonstrated a significant time effect on the percentage of freezing. The unpaired CTR and CUS groups increased freezing during the post-US period compared to the pre-US period. During the unpaired arena sessions (first to fifth), there was a significant decrease in freezing, indicating that the defensive behavior was context-dependent, and the animals did not generalize aversive memory (Fig. 4B). However, unpaired CUS animals exhibited more freezing when compared to CTR on day 1 or extinction test in the paired arena. These findings were confirmed by paired comparisons of the first unpaired arena session and extinction test, which revealed a CUS-induced increase in freezing during both periods (Fig. 4B’ and B”). Furthermore, when both unpaired groups were placed in the paired arena during the extinction test, they exhibited an increase in freezing compared to their respective period in the unpaired arena.

Nonetheless, the CTR group had less freezing than the post-US period. Additionally, unpaired CUS animals also displayed decreased freezing during the extinction sessions compared to their respective group in post-US. However, this decrease was smaller than that of the unpaired CTR group throughout the unpaired arena sessions (Fig. 4B”’) (statistical analyses are summarized in SI Appendix, Table S6). These results suggest that the freezing reduction is associated with successive re-exposures to the paired arena, despite the time lapse between conditioning and extinction test having a negligible effect.

Supporting the higher freezing response in CUS animals than CTR ones during the retrieval test, which gradually decreased during the extinction sessions, statistical analysis regarding the freezing gain ratio revealed a significant stress effect over time. This effect was reflected by a decreased freezing gain ratio during the retrieval test compared to the post-US period, which gradually recovered throughout the extinction sessions (Fig. 3C). During the extinction test, the freezing gain ratio in CUS animals was similar to the CTR group (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, despite post hoc analysis not indicating a significant difference in the freezing gain ratio for the CTR group between the retrieval test and extinction test (Fig. 3C), a separate analysis comparing the retrieval and extinction tests revealed an elevated freezing gain ratio in the extinction test for both the CTR and CUS groups (Fig. 3C’ and C”) (statistical analyses are summarized in SI Appendix, Table S5). For the CTR and CUS unpaired groups, we observed an elevated freezing absence ratio during all sessions in the non-paired arena and a reduced freezing absence ratio during the extinction test (Fig. 4C). Further analysis of the retrieval and extinction tests validated these observations (Fig. 4C’ and C”) (statistical analyses are summarized in SI Appendix, Table S6).

Therefore, although CUS does not interfere with the acquisition and extinction of aversive memory, it causes greater responsiveness to the paired context by increasing freezing during the retrieval test. Additionally, while CUS does not induce generalization, it sensitizes the defensive response in an unpaired context, and exposure to the paired context is fundamental for the animal to extinguish this memory.

CUS behavioral effects are concomitant to increased GC signaling and excitatory pathway modulation

Considering the importance of GCs in stress response, hippocampal neuronal activation, and defensive behaviors, as well as the involvement of excitatory pathways mediated by AMPA glutamatergic receptor (in particular the glutamate subunit 1, GluA1) and adrenergic receptors in hippocampal plasticity [19, 27, 28], we sought to examine the phosphorylation state as an indication of function gain and the expression of key HP-related proteins in control and CUS animals by Western blot.

Statistical analyses showed a significant stress effect on cell signaling proteins. During the retrieval test, the CUS group displayed increased MR translocation, nuclear and cytosolic GR expression, and decreased P-glycoprotein expression (Fig. 5.1C–E and G), indicating an increase in MR and GR activation probably due to a rise in intracellular GC availability. Additionally, there is a tendency towards an increase in glutamatergic signaling and a decrease in cumulative, but not acute, neuronal activation, measured by phosphoGluA1R(Ser845) and FosB, respectively, without changing Egr1 expression (Fig. 5.2B, 5.3B, and 5.3A). In contrast, during the extinction test, there was an increase in cytosolic GR and FosB and a decrease in GluA1R, phosphoGluA1R(Ser845), and β2-adrenergic receptor, without any effects on Egr1 expression (Fig. 5.1E, 5.2A–C, 5.3B and 5.3A) (statistical analyses are summarized in SI Appendix, Table S7). Therefore, our results suggest that the 14-day CUS is associated with concomitant changes in the expression of relevant proteins for dHP plasticity during retrieval or extinction tests.

The control group (CTR) is always represented in green, and the stressed group (CUS) in pink. Regarding GC signaling, CUS causes no effect on nuclear MR (1A) and cytosolic MR (1B) in the retrieval and extinction test but increases MR translocation in the retrieval period (1C). Moreover, it caused an increase in nuclear GR (1D) during retrieval and an increase in cytosolic GR (1E) during the retrieval and extinction test, with no effect on translocation (1F). An increase in P-Glycoprotein was also observed during retrieval (1G). For excitatory signaling, there was a cytosolic decrease of GluA1R (2A), phosphoGluA1R(Ser845) (2B), and β2-adrenergic (2C) during extinction. CUS caused no effect on Egr1 (3A) but increased cytosolic FosB during the extinction test (3B). Results are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 4–7 animals/group in 1A-G, n = 4–7 animals/group in 2A–C, and n = 3–6 animals/group in 3A and B). In 1C, 1D, 1E, 1G, 2B, 2C and 3B, *, ** and *** (p < 0.05, p < 0.01 and p < 0.001) vs. their respective group CTR group. In 2B and 3B, a statistical trend is observed (p = 0.07) vs. their respective group CTR group.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that 14-day CUS induces behavioral, biochemical, and molecular changes, resulting in greater chronic stress-induced alertness when challenged with an aversive situation (e.g., EPM and retrieval test). These changes shift the animal’s behavioral strategies to a defensive one, activating compensatory mechanisms related to the aversive memory that allow them to overcome the disadvantageous stress effects associated with this highly aroused state, evidenced by higher freezing.

CUS increased anxiety-like behavior and induced a behavioral profile characterized by low open-arm exploration and a higher and constant frequency of unprotected risk assessment over time [29], suggesting that the stressed animals were better habituated to the novelty than the non-stressed ones. This behavior was more evident in the aversive conditioning because CUS caused greater responsiveness to the contextual aversive stimuli, facilitating the increased expression of freezing during the retrieval test. Interestingly, increased arousal in the retrieval test was not due to better acquisition and did not improve extinction. Our results demonstrate that the higher freezing in the retrieval test was overcome during the extinction sessions with high extinction gain, resulting in an aversive memory extinction similar to the CTR group. Additionally, we showed that these CUS effects on aversive memory were unrelated to memory generalization in other contexts. Thus, CUS induced new behavioral responses and were insufficient to render an allostatic breakdown, producing protective hormetic effects that could improve the organism’s performance in an aversive situation.

Several studies showed that chronic stress can initiate adaptive mechanisms that modify physiological functions [30], enabling individuals to cope with stressful situations or future threats. Increased GC secretion from an activated HPA axis is crucial in these responses. However, excessive GC secretion diminishes its benefits, ultimately leading to maladaptive consequences, such as HPA axis hyperactivity, a risk factor for systemic, neuropsychiatric diseases and cognitive deficits [31,32,33,34,35]. Anxiety- and depression-like behaviors, fear, and cognition deficits have been reported after CUS [4, 36,37,38]. In our 14-day study, the basal serum CORT concentration was elevated 24 hours after the last CUS session during the EPM test or pre-US period, corroborating previous studies [4, 39]. The CUS-induced CORT increase is frequently linked to impaired HPA axis negative feedback control, leading to excessive GC release and allostasis disruption, culminating in an ineffective allostatic response and exhaustion of the organism [40]. Despite basal CORT concentration (24 hours after the last stress) being more elevated in CUS animals than non-CUS animals, CORT concentration during conditioning (30 minutes post-US) did not change in either group. After the retrieval test (30 minutes post-CS), when the animals returned to the same conditioning arena context without the US, CORT concentration increased equally in stressed and non-stressed animals, highlighting that the context was aversive enough to activate the HPA axis, regardless of the previous, transitory HPA axis activation in CUS animals. During the extinction test, the CORT concentration was similar to the basal one.

Previous studies showed that after the conditioning period (post-US), the increase in CORT concentration is dependent on the footshock intensity, with a positive correlation between the augment in CORT concentration and freezing behavior following the conditioning period [26, 41, 42]. However, these studies considered the US itself a stressful event and presented limited responses to this stimulus without considering the influence of previous stressors. Our experimental protocol involved a single 0.5 mA footshock for 1 s, whereas the other studies conditioned the animals with three footshocks (0.2–1 mA) [41, 42]. Moreover, we previously exposed the animals to a 14-day CUS, transiently increasing basal CORT concentrations, which was still insufficient to elicit sustained CORT release alterations (i.e., HPA axis sensitization during a second aversive challenge (i.e., conditioning) or extinction test.

Although the HPA axis presents similar responses, during the retrieval test, some changes in CUS-associated protein expression were evident in the dHP, suggesting increased intracellular GC availability (via decreased P-glycoprotein) from MR and GR expression, but not for glutamate and norepinephrine receptors or acute and cumulative neuronal activation. Nevertheless, a net increase in cytosolic GR expression was maintained until the extinction test, the glutamate and norepinephrine receptors were decreased, and a cumulative, not immediate, neuronal activation was observed. Previous results demonstrate that CORT and norepinephrine interact to rapidly regulate hippocampal AMPA receptor function, in which the co-administration of CORT and the β-adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol increases the phosphorylation of the AMPAR subunit GluA1R(Ser845). Furthermore, the association of isoproterenol and CORT enhanced miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSC) frequency [43]. In general, acquiring aversive memory leads to an increased insertion of AMPA receptors containing the GluA1 subunit into the synaptic membrane. In contrast, the internalization of these receptors points out memory extinction [44, 45]. Our previous work demonstrated that elevated hippocampal GluA1R(Ser845) is linked to late impairments in acute stress-induced aversive memory extinction. Additionally, in the dHP CA1 area and the dentate gyrus, the β-adrenergic excitability facilitation is markedly attenuated by CORT pretreatment via a slow and presumably gene-mediated pathway [28]. Gray [46] suggests that following the detection of novel or unexpected events, the pivotal hippocampal function is to augment the levels of arousal and attentional processing, increasing contextual investigation. In this sense, the dHP appears to be essential in modulating the attentional intensity or perceived salience of stimulus representations [47]. Our findings reinforce these previous results, indicating that 14-day CUS alters dHP-GC cellular machinery, and the glutamatergic and norepinephrine receptors contribute to adaptative behavioral outcomes during aversive situations, adding importance to the perceptual learning promoted by dHP for the retrieval and extinction memory process.

Several studies indicate that increased GC concentrations modulate the animals’ behavioral and cognitive responses to challenging situations, including attention, perception, memory, and emotional processing. Furthermore, studies suggest that the dHP influences the adaptive responses of GCs, potentially altering anxiety [48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Our results demonstrated that 24 hours after the last stress session, 14-day CUS rats displayed increased alertness, characterized by decreased EPM open-arm exploration [55]. However, although the stressed animals spent less time in the open arm, ethological measures of SAP and head-dipping behaviors did not change regarding their percentage in the protected area. Less time spent in the open arm did not cause a decrease in the risk assessment profile over time; instead, it caused a constantly high expression throughout the EPM test. These results suggest a compensatory shift in risk assessment strategy over time, where the animal increases the constancy of behavior due to decreased exploration. Contrary to our findings, previous studies demonstrated that chronic ultra-mild stress (CUMS) in mice increased exploratory activity and attention deficit, impairing decision-making [56], and 28 days of chronic mild stress (CMS) elevated risk assessment behavior in mice [57]. Others showed an anxiolytic-like profile [58] or ambiguous anxiety-like behavior in rats [59]. Indeed, different forms of chronic stress (e.g., immobilization and electric shock for 14 days) produce aberrant choices and high-risk/high-reward conditions, resembling non-optimal decision-making under conflict [60]. Based on our findings, we hypothesize that when animals experience minimal stress—exposure to various mild stressors—over a short duration, they tend to adopt conservative strategies to ensure their safety.

Furthermore, in our previous study, we did not observe a CUS-induced anxiety-like effect [4], and this difference can be explained by the alteration in the aversiveness of the EPM employed in this study. For example, using lower luminosity (10 lux in both open and closed arms) enabled us to detect disparities in anxiety-like behavior. Other studies report that even subtle EPM modifications can influence an animal’s anxiety responses [61, 62] Additionally, rats show greater open arm exploration under low (01 lux) than under high luminosity [25, 63]. (e.g., difference in luminosity between the open and closed arms is indeed anxiogenic [64]). Importantly, variations in CUS protocols, such as type of stressor(s), frequency per day, duration, rat or mouse strains, animal genders and even home cage distribution, can alter ethological parameters.

It has been reported that the temporality and intensity of the stressor can influence mnemonic processes [65] and the individual’s alertness. Multiple studies demonstrate that escalating the footshock intensity or frequency facilitates mnemonic processes, leading to a greater manifestation of defensive behavior in rats [66,67,68]. Recent research examining the impact of previous acute or chronic stress on subsequent stressful challenges has revealed that the preceding allostatic processes can modulate the mnemonic effects induced by the following challenges [11, 21, 69]. Chronic stress before conditioning sessions resulted in elevated startle responses, increased freezing, and impaired extinction memory, even after a subsequent stress-free retrieval period [70, 71]. Similarly, in our study, CUS animals exhibited higher freezing after conditioning than their respective group in the post-US period or the CTR in the retrieval test. Although the initial increase in freezing can predict maladaptive changes regarding the extinction of an aversive memory [70], we observed a compensatory mechanism associated with increased extinction. During the initial three extinction sessions, the CUS animals maintained a significant extinction gain until the extinction test. Thus, CUS-induced increased freezing during retrieval does not implicate impairment of aversive memory extinction in rats. We hypothesize that this effect occurs because CUS increases the arousal (alertness) and surveillance of the environment (context), improving decision-making and strategic behaviors, possibly due to enhanced environmental information processing.

It is unclear why the CUS effects on freezing responsiveness are associated with increased basal CORT, which should be explored in future studies. CORT sensitization of extra-HPA axis structures, such as the dHP, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex, regulates memory processes and defensive behaviors through MR and GR activation [9, 72]. We observed increases in MR translocation into the cytosol (i.e., activation) and GR nuclear expression (i.e., higher activation) and a decrease in P-glycoprotein expression. The latter is a transmembrane unidirectional efflux pump, densely expressed in the blood–brain barrier and has a high affinity for GCs [73,74,75]. The attenuated P-glycoprotein expression in CUS animals suggests that more intracellular GCs are available to bind to their receptors in the dHP. Given that CORT cannot fully account for the facilitation of memory formation and retrieval processes following chronic stress [76], it is plausible that norepinephrine signaling sensitization in the dHP influences the aversive memory retrieval process.

Previous studies have demonstrated the potential of catecholamines to modulate memory processes [77,78,79], and effects on catecholaminergic pathways have been observed in animals submitted to CUS [4]. We observed increased alertness and vigilance driven by heightened anxiety, counterbalanced by cognitive improvement. Moreover, it only required a few re-exposures to the aversive context to facilitate appropriate adaptation through efficient aversive memory extinction, ultimately decreasing freezing in CUS animals. This ‘advantageous’ effect does not negatively affect the animal in other areas, such as a possible increase in the generalization of aversive memory. Accurately assessing a threat necessitates the capability to effectively distinguish between the information associated with security and the danger and precisely discriminate the possibility that a prediction will occur [80]. An increase in aversive memory generalization could trigger aberrant defensive behaviors in situations unrelated to their original occurrence [81, 82]. Studies indicate that emotional arousal induced by stress or anxiety significantly impacts memory systems, primarily involving the HP and dorsal striatum. For example, when subjected to a learning strategy test, mice and humans can activate GC-dependent mechanisms to shift behavioral strategies from HP-dependent spatial learning to the dorsal striatum-dependent stimulus-response pathway [83,84,85,86]. Another aspect to be considered is the stress impact on aversive memory generalization, an important characteristic associated with PTSD and anxiety [87, 88], where random or subjective stimuli can trigger the symptoms of these disorders in situations unrelated to the traumatic events in their original occurrence. When we analyzed the generalization in the unpaired groups, CTR and CUS exhibited increased freezing compared to their respective groups in the post-US period. However, when exposed to the unpaired context during the extinction sessions, both groups displayed reduced freezing behavior, indicating the absence of generalization. Indeed, the degree of generalization has been linked to the intensity of the stress. For example, memory retention induced by a 1 or 3 mA footshock exhibited significant generalization to different contexts after training, whereas 0.6 mA footshocks did not produce this effect [42, 89]. Additionally, when CUS or CTR animals were exposed to the paired arena during the extinction test, there was an increase in freezing behavior, confirming that context is necessary for extinction to occur [11, 21, 90]. Evidence indicates that the dHP plays a vital role in contextual discrimination by restricting the generalization of aversive memory [91,92,93]. Interestingly, while the CTR and CUS groups did not demonstrate generalization when analyzing the extinction sessions separately, we observed that the CUS animals exhibited higher freezing levels than the CTR. However, we found no significant difference when comparing the extinction gain between the unpaired groups. In this case, the 14-day CUS may modify emotional arousal in unpaired contexts, enhancing the animals’ responsiveness but to a degree that remains adaptive without leading to generalization.

It is important to note that the current study’s focus on males is a limitation, as the effects of CUS on aversive memory processing may differ between sexes. Previous research indicates that male and female brains may utilize distinct neuronal pathways for processing aversive memories, which can have implications for understanding various neuropsychiatric disorders, including PTSD [94, 95]. Therefore, future research should prioritize the inclusion of female subjects to elucidate these potential differences and gain a comprehensive understanding of how stress influences memory in both sexes.

Collectively, our results point to CUS having a hormetic effect on anxiety and memory processes. Herein, the 14-day CUS protocol better adapts animals to novelty, augmenting contextual arousal (alertness). These changes were accompanied by alterations in the expression of receptors and proteins involved in glutamatergic and norepinephrine signaling and differential MR nuclear translocation in the dHP. These responses could trigger a switch from maladaptive to coping mechanisms, allowing animals to express heightened defensive behavior and avoid compromising allostatic responses. Understanding these complexities is pivotal, and new avenues for nuanced therapeutic interventions could reshape our perspective on stress resilience.

Data availability

All data supporting this study’s findings are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, Cornett J, Whiteford H, Saxena S. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394:240–8.

Eliezer Y, Deshe N, Hoch L, Iwanir S, Pritz CO, Zaslaver A. A memory circuit for coping with impending adversity. Curr Biol. 2019;29:1573–1583.e4.

McEwen BS, Wingfield JC. The concept of allostasis in biology and biomedicine. Horm Behav. 2003;43:2–15.

Malta MB, Martins J, Novaes LS, Dos Santos NB, Sita L, Camarini R, et al. Norepinephrine and glucocorticoids modulate chronic unpredictable stress-induced increase in the type 2 CRF and glucocorticoid receptors in brain structures related to the HPA axis activation. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58:4871–85.

Van de Kar LD, Blair ML. Forebrain pathways mediating stress-induced hormone secretion. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1999;20:1–48.

Maggio N, Segal M. Cellular basis of a rapid effect of mineralocorticosteroid receptors activation on LTP in ventral hippocampal slices. Hippocampus. 2012;22:267–75.

Pasricha N, Joels M, Karst H. Rapid effects of corticosterone in the mouse dentate gyrus via a nongenomic pathway. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23:143–7.

Prager EM, Johnson LR. Stress at the synapse: signal transduction mechanisms of adrenal steroids at neuronal membranes. Sci Signal. 2009;2:re5.

Schwabe L, Joëls M, Roozendaal B, Wolf OT, Oitzl MS. Stress effects on memory: an update and integration. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1740–9.

Birnbaum SG, Podell DM, Arnsten AF. Noradrenergic alpha-2 receptor agonists reverse working memory deficits induced by the anxiogenic drug, FG7142, in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67:397–403.

Albernaz-Mariano KA, Demarchi Munhoz C. The infralimbic mineralocorticoid blockage prevents the stress-induced impairment of aversive memory extinction in rats. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:343.

Dudai Y. Predicting not to predict too much: how the cellular machinery of memory anticipates the uncertain future. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364:1255–62.

Rauch SL, Shin LM, Phelps EA. Neurocircuitry models of posttraumatic stress disorder and extinction: human neuroimaging research–past, present, and future. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:376–82.

Yehuda R, Joels M, Morris RG. The memory paradox. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:837–9.

Bremner JD, Narayan M, Staib LH, Southwick SM, McGlashan T, Charney DS. Neural correlates of memories of childhood sexual abuse in women with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1787–95.

Ramirez S, Liu X, Lin PA, Suh J, Pignatelli M, Redondo RL, et al. Creating a false memory in the hippocampus. Science. 2013;341:387–91.

Redondo RL, Kim J, Arons AL, Ramirez S, Liu X, Tonegawa S. Bidirectional switch of the valence associated with a hippocampal contextual memory engram. Nature. 2014;513:426–30.

Ghandour K, Ohkawa N, Fung CCA, Asai H, Saitoh Y, Takekawa T, et al. Orchestrated ensemble activities constitute a hippocampal memory engram. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2637.

Yoo SW, Bae M, Tovar-Y-Romo LB, Haughey NJ. Hippocampal encoding of interoceptive context during fear conditioning. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e991–e991.

Bierwirth P, Stockhorst U. Role of noradrenergic arousal for fear extinction processes in rodents and humans. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2022;194:107660.

Novaes LS, Bueno-de-Camargo LM, Munhoz CD. Environmental enrichment prevents the late effect of acute stress-induced fear extinction deficit: the role of hippocampal AMPA-GluA1 phosphorylation. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:18.

Willner P. Chronic mild stress (CMS) revisited: consistency and behavioural-neurobiological concordance in the effects of CMS. Neuropsychobiology. 2005;52:90–110.

Munhoz CD, Lepsch LB, Kawamoto EM, Malta MB, Lima Lde S, Avellar MC, et al. Chronic unpredictable stress exacerbates lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of nuclear factor-kappaB in the frontal cortex and hippocampus via glucocorticoid secretion. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3813–20.

Novaes LS, Bueno-de-Camargo LM, Shigeo-de-Almeida A, Juliano VAL, Goosens K, Munhoz CD. Genomic glucocorticoid receptor effects guide acute stress-induced delayed anxiety and basolateral amygdala spine plasticity in rats. Neurobiol Stress. 2024;28:100587.

Garcia AM, Cardenas FP, Morato S. Effect of different illumination levels on rat behavior in the elevated plus-maze. Physiol Behav. 2005;85:265–70.

Fanselow MS, Bolles RC. Naloxone and shock-elicited freezing in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1979;93:736–44.

Joels M. Corticosteroid effects in the brain: U-shape it. Trends Pharm Sci. 2006;27:244–50.

Joels M, de Kloet ER. Effects of glucocorticoids and norepinephrine on the excitability in the hippocampus. Science. 1989;245:1502–5.

Rodgers RJ, Haller J, Holmes A, Halasz J, Walton TJ, Brain PF. Corticosterone response to the plus-maze: high correlation with risk assessment in rats and mice. Physiol Behav. 1999;68:47–53.

Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:397–409.

Herman JP. Neural control of chronic stress adaptation. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:61.

Juruena MF, Eror F, Cleare AJ, Young AH. The role of early life stress in HPA axis and anxiety. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1191:141–53.

DeMorrow S. Role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in health and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:986.

Bosch NM, Riese H, Dietrich A, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Oldehinkel AJ. Preadolescents’ somatic and cognitive-affective depressive symptoms are differentially related to cardiac autonomic function and cortisol: the TRAILS study. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:944–50.

Berardelli I, Serafini G, Cortese N, Fiaschè F, O'Connor RC, Pompili M. The involvement of hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in suicide risk. Brain Sci. 2020;10:653.

Bondi CO, Rodriguez G, Gould GG, Frazer A, Morilak DA. Chronic unpredictable stress induces a cognitive deficit and anxiety-like behavior in rats that is prevented by chronic antidepressant drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:320–31.

Matuszewich L, Karney JJ, Carter SR, Janasik SP, O'Brien JL, Friedman RD. The delayed effects of chronic unpredictable stress on anxiety measures. Physiol Behav. 2007;90:674–81.

Rodríguez Echandía EL, Gonzalez AS, Cabrera R, Fracchia LN. A further analysis of behavioral and endocrine effects of unpredictable chronic stress. Physiol Behav. 1988;43:789–95.

Leite JA, Orellana AM, Andreotti DZ, Matumoto AM, de Souza Ports NM, de Sá Lima L, et al. Ouabain reverts CUS-induced disruption of the hpa axis and avoids long-term spatial memory deficits. Biomedicines. 2023;11:1177.

Kling MA, Coleman VH, Schulkin J. Glucocorticoid inhibition in the treatment of depression: can we think outside the endocrine hypothalamus?. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:641–9.

Cordero MI, Merino JJ, Sandi C. Correlational relationship between shock intensity and corticosterone secretion on the establishment and subsequent expression of contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:885–91.

Dos Santos Corrêa M, Vaz BDS, Grisanti GDV, de Paiva JPQ, Tiba PA, Fornari RV. Relationship between footshock intensity, post-training corticosterone release and contextual fear memory specificity over time. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;110:104447.

Zhou M, Hoogenraad CC, Joëls M, Krugers HJ. Combined beta-adrenergic and corticosteroid receptor activation regulates AMPA receptor function in hippocampal neurons. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:516–24.

Myers KM, Carlezon WA Jr., Davis M. Glutamate receptors in extinction and extinction-based therapies for psychiatric illness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:274–93. p.

Rumpel S, LeDoux J, Zador A, Malinow R. Postsynaptic receptor trafficking underlying a form of associative learning. Science. 2005;308:83–8.

Gray JA. Précis of The neuropsychology of anxiety: an enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system. Behav Brain Sci. 1982;5:469–84.

Sanderson DJ, McHugh SB, Good MA, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH, Rawlins JN, et al. Spatial working memory deficits in GluA1 AMPA receptor subunit knockout mice reflect impaired short-term habituation: evidence for Wagner’s dual-process memory model. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:2303–15.

Raulo A, Dantzer B. Associations between glucocorticoids and sociality across a continuum of vertebrate social behavior. Ecol Evol. 2018;8:7697–716.

Koolhaas JM, de Boer SF, Coppens CM, Buwalda B. Neuroendocrinology of coping styles: towards understanding the biology of individual variation. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2010;31:307–21.

Erickson K, Drevets W, Schulkin J. Glucocorticoid regulation of diverse cognitive functions in normal and pathological emotional states. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:233–46.

McEwen BS, Magarinos AM. Stress and hippocampal plasticity: implications for the pathophysiology of affective disorders. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2001;16:S7–S19.

Popoli M, Yan Z, McEwen BS, Sanacora G. The stressed synapse: the impact of stress and glucocorticoids on glutamate transmission. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;13:22–37.

Piazza PV, Deroche V, Deminière JM, Maccari S, Le Moal M, Simon H. Corticosterone in the range of stress-induced levels possesses reinforcing properties: implications for sensation-seeking behaviors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11738–42.

McLay RN, Freeman SM, Zadina JE. Chronic corticosterone impairs memory performance in the Barnes maze. Physiol Behav. 1998;63:933–7.

Pellow S, Chopin P, File SE, Briley M. Validation of open:closed arm entries in an elevated plus-maze as a measure of anxiety in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1985;14:149–67.

Pardon MC, Pérez-Diaz F, Joubert C, Cohen-Salmon C. Influence of a chronic ultramild stress procedure on decision-making in mice. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2000;25:167–77.

Wang C, Li M, Sawmiller D, Fan Y, Ma Y, Tan J, et al. Chronic mild stress-induced changes of risk assessment behaviors in mice are prevented by chronic treatment with fluoxetine but not diazepam. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;116:116–28.

D’Aquila PS, Brain P, Willner P. Effects of chronic mild stress on performance in behavioural tests relevant to anxiety and depression. Physiol Behav. 1994;56:861–7.

Kompagne H, Bárdos G, Szénási G, Gacsályi I, Hársing LG, Lévay G. Chronic mild stress generates clear depressive but ambiguous anxiety-like behaviour in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2008;193:311–4.

Friedman A, Homma D, Bloem B, Gibb LG, Amemori KI, Hu D, et al. Chronic stress alters striosome-circuit dynamics, leading to aberrant decision-making. Cell. 2017;171:1191–1205 e28.

Martínez JC, Cardenas F, Lamprea M, Morato S. The role of vision and proprioception in the aversion of rats to the open arms of an elevated plus-maze. Behav Process. 2002;60:15–26.

Cardenas F, Lamprea MR, Morato S. Vibrissal sense is not the main sensory modality in rat exploratory behavior in the elevated plus-maze. Behav Brain Res. 2001;122:169–74.

Garcia AM, Cardenas FP, Morato S. The effects of pentylenetetrazol, chlordiazepoxide and caffeine in rats tested in the elevated plus-maze depend on the experimental illumination. Behav Brain Res. 2011;217:171–7.

Pereira LO, da Cunha IC, Neto JM, Paschoalini MA, Faria MS. The gradient of luminosity between open/enclosed arms, and not the absolute level of Lux, predicts the behaviour of rats in the plus maze. Behav Brain Res. 2005;159:55–61.

Sandi C, Pinelo-Nava MT. Stress and memory: behavioral effects and neurobiological mechanisms. Neural Plast. 2007;2007:78970.

Witnauer JE, Miller RR. Conditioned suppression is an inverted-U function of footshock intensity. Learn Behav. 2013;41:94–106.

Bali A, Jaggi AS. Electric foot shock stress: a useful tool in neuropsychiatric studies. Rev Neurosci. 2015;26:655–77.

Louvart H, Maccari S, Lesage J, Léonhardt M, Dickes-Coopman A, Darnaudéry M. Effects of a single footshock followed by situational reminders on HPA axis and behaviour in the aversive context in male and female rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:92–9.

Mitra R, Sapolsky RM. Acute corticosterone treatment is sufficient to induce anxiety and amygdaloid dendritic hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5573–8.

McGuire J, Herman JP, Horn PS, Sallee FR, Sah R. Enhanced fear recall and emotional arousal in rats recovering from chronic variable stress. Physiol Behav. 2010;101:474–82.

Miracle AD, Brace MF, Huyck KD, Singler SA, Wellman CL. Chronic stress impairs recall of extinction of conditioned fear. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2006;85:213–8.

Shin LM, Liberzon I. The neurocircuitry of fear, stress, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:169–91.

Bloise, E, Matthews SG Multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein (P-gp), glucocorticoids, and the stress response, in Stress: Physiology, Biochemistry, and Pathology, G Fink, Editor. 2019, Academic Press. pp. 227-41.

Schoenfelder Y, Hiemke C, Schmitt U. Behavioural consequences of p-glycoprotein deficiency in mice, with special focus on stress-related mechanisms. J Neuroendocrinol. 2012;24:809–17.

Torres-Vergara P, Escudero C, Penny J. Drug transport at the brain and endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia: implications and perspectives. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1502.

Kulp AC, Lowden BM, Chaudhari S, Ridley CA, Krzoska JC, Barnard DF, et al. Sensitized corticosterone responses do not mediate the enhanced fear memories in chronically stressed rats. Behav Brain Res. 2020;382:112480.

Roozendaal B, Quirarte GL, McGaugh JL. Glucocorticoids interact with the basolateral amygdala beta-adrenoceptor–cAMP/cAMP/PKA system in influencing memory consolidation. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:553–60.

Schwabe L, Hermans EJ, Joëls M, Roozendaal B. Mechanisms of memory under stress. Neuron. 2022;110:1450–67.

Roozendaal B, Mirone G. Opposite effects of noradrenergic and glucocorticoid activation on accuracy of an episodic-like memory. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020;114:104588.

Maren S, Phan KL, Liberzon I. The contextual brain: implications for fear conditioning, extinction and psychopathology. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:417–28.

Dunsmoor JE, Murphy GL. Categories, concepts, and conditioning: how humans generalize fear. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19:73–7.

Asok A, Kandel ER, Rayman JB. The Neurobiology of Fear Generalization. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:329.

Schwabe L, Dalm S, Schächinger H, Oitzl MS. Chronic stress modulates the use of spatial and stimulus-response learning strategies in mice and man. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;90:495–503.

Schwabe L, Schächinger H, de Kloet ER, Oitzl MS. Corticosteroids operate as a switch between memory systems. J Cogn Neurosci. 2010;22:1362–72.

Packard MG, Goodman J. Emotional arousal and multiple memory systems in the mammalian brain. Front Behav Neurosci. 2012;6:14.

Schwabe L, Oitzl MS, Philippsen C, Richter S, Bohringer A, Wippich W, et al. Stress modulates the use of spatial versus stimulus-response learning strategies in humans. Learn Mem. 2007;14:109–16.

Fenster RJ, Lebois LAM, Ressler KJ, Suh J. Brain circuit dysfunction in post-traumatic stress disorder: from mouse to man. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19:535–51.

Lis S, Thome J, Kleindienst N, Mueller-Engelmann M, Steil R, Priebe K, et al. Generalization of fear in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychophysiology. 2020;57:e13422.

Finsterwald C, Steinmetz AB, Travaglia A, Alberini CM. From memory impairment to posttraumatic stress disorder-like phenotypes: the critical role of an unpredictable second traumatic experience. J Neurosci. 2015;35:15903–15.

Hobin JA, Goosens KA, Maren S. Context-dependent neuronal activity in the lateral amygdala represents fear memories after extinction. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8410–6.

Frankland PW, Cestari V, Filipkowski RK, McDonald RJ, Silva AJ. The dorsal hippocampus is essential for context discrimination but not for contextual conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:863–74.

Maren S, Aharonov G, Fanselow MS. Neurotoxic lesions of the dorsal hippocampus and Pavlovian fear conditioning in rats. Behav Brain Res. 1997;88:261–74.

McHugh TJ, Jones MW, Quinn JJ, Balthasar N, Coppari R, Elmquist JK, et al. Dentate gyrus NMDA receptors mediate rapid pattern separation in the hippocampal network. Science. 2007;317:94–9.

Florido A, Velasco ER, Romero LR, Acharya N, Marin Blasco IJ, Nabás JF, et al. Sex differences in neural projections of fear memory processing in mice and humans. Sci Adv. 2024;10:eadk3365.

Florido A, Velasco ER, Soto-Faguás CM, Gomez-Gomez A, Perez-Caballero L, Molina P, et al. Sex differences in fear memory consolidation via Tac2 signaling in mice. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2496.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Guiomar Wiesel for technical support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP 2016/03572-3, 2019/00908-9, and 2021/04077-4) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq 422523/2016-0) to CDM. KAAM was supported by FAPESP (2021/14690-5). LSN was supported by FAPESP (2018/19599-3). LMBC was supported by FAPESP (2018/15982-7). GD was supported by FAPESP (2017/16549-2). JLSP was supported by CNPq (140436/2022-7) and FAPESP (2022/16523-1). EAD was supported by FAPESP (2022/12679-7 and 2023/09933-1). CDM is a research fellow from CNPq. This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KAAM: designed research, performed research, analyzed data, wrote the paper; MBM: designed research, performed research, analyzed data, wrote the paper (equal); LMBC: performed research; EAD: performed research, analyzed data; LSN: designed research, performed research, analyzed data; GD: performed research; JLSP: performed research; CDM: designed research, analyzed data, contributed unpublished reagents/analytic tools, wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Albernaz-Mariano, K.A., Malta, M.B., Bueno-de-Camargo, L.M. et al. Unpredictable stress boosts perceptual learning and alters glucocorticoid and norepinephrine receptors in rats’ dorsal hippocampus. Transl Psychiatry 15, 508 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03716-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03716-6