Abstract

Subjective cognitive decline (SCD) serves as an initial symptom of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The accumulation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) is acknowledged as a critical risk factor for the eventual progression to mild cognitive impairment or dementia in individuals with SCD, highlighting the necessity for early detection and intervention. Previous studies have identified the retina and choriocapillaris as potential biomarkers for AD; however, these investigations have not thoroughly examined large and medium-sized choroidal vessels. Ultra-wide swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography (SS-OCTA), an innovative noninvasive imaging modality, facilitates rapid and precise quantitative assessment of retinal and choroidal boundaries and vasculature through dynamic scanning, encompassing large and medium-sized choroidal vessels. This study aims to characterize the outer retinal and choroidal vasculature and structure in individuals with SCD, examine the correlation between altered choroidal vasculature parameters and amyloid burden, and the presence of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele in SCD participants, to identify potential ocular biomarkers for high-risk SCD screening. In this study, 57 individuals with SCD and 45 matched normal controls were enrolled. Ultra-wide SS-OCTA was employed to assess the thickness of the outer retina and choroid and the blood flow within the choriocapillaris and large, medium-sized choroidal vessels. 18F-Florbetapir positron emission tomography scans were performed to classify amyloid-positive-SCD (Aβ + SCD) and amyloid-negative-SCD (Aβ-SCD) groups. Plasma Aβ42/40 and APOE ε4 genotypes were also measured. Compared with normal controls, individuals with SCD exhibited a significant increase in the choroidal vessel index and a reduction in outer retinal thickness. The Aβ + SCD group demonstrated an elevated choriocapillaris flow area relative to the Aβ- SCD group. Moreover, a negative correlation was observed between the choriocapillaris flow area and plasma Aβ42/40 levels in the SCD cohort. Among SCD participants, APOE ε4 carriers displayed increased choriocapillaris flow area and choroidal vessel volume compared to APOE ε4 non-carriers. Our findings provide intriguing insights into the relationship between amyloid pathology and changes in the choriocapillaris flow area. The choroid may serve as a potential biomarker for screening Aβ + SCD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Subjective cognitive decline (SCD), defined as persistent self-reported perception of cognitive decline despite normal neuropsychological test performance [1], represents the initial symptomatic stage of preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). The pathological hallmarks of AD, including abnormal deposition of amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles, begin accumulating approximately 15–20 years prior to the manifestation of clinical symptoms [2, 3]. Recent advancements in disease-modifying therapies have shown promising results in clearing brain amyloid and slowing cognitive decline. Still, these treatments are effective only in the early stages of AD [3]. Importantly, baseline amyloid deposition and lower plasma Aβ 42/40 ratios have been strongly associated with future cognitive decline in individuals with SCD [4, 5]. These findings highlight the critical need for early identification of amyloid-positive (Aβ + ) individuals within the SCD population to enable timely intervention.

Despite the importance of early amyloid detection, current gold-standard methods, positron emission tomography (PET) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis are limited by high costs, invasiveness, and logistical challenges, making them unsuitable for large-scale screening. Blood-based biomarkers present significant potential to revolutionize the diagnosis and prognosis of AD. Notably, abnormal levels of plasma phosphorylated tau (p-tau) 181 and p-tau 217 indicate a high probability of AD pathophysiology [6]. However, prior to their widespread clinical implementation, it is imperative to establish assay standardization, generate appropriate thresholds, and verify these biomarkers across diverse cohorts. This gap underscores the urgent need for noninvasive, cost-effective biomarkers that can facilitate the widespread early detection of AD.

Mounting evidence suggests that the eye, particularly the retina and choroid, may serve as a surrogate for cerebral amyloid pathology. Aβ deposits have been identified in the eyes of AD patients [7,8,9], and ocular changes have emerged as promising biomarkers for AD. Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA), a noninvasive imaging technique, allows for rapid, quantitative assessment of retinal and choroidal thickness and blood flow, offering a cost-effective and scalable screening tool [10,11,12]. Our previous work has demonstrated that retinal microvasculature and structure exhibit early alterations in individuals with SCD [13], further supporting the potential of ocular biomarkers in preclinical AD detection. The choroid, a highly vascularized layer between the retina and the sclera, supplies 85% of the retina’s blood flow and is critical in maintaining retinal metabolism [14]. Notably, the Choroid has been implicated in AD and age-related macular degeneration (AMD), with shared pathogenic mechanisms involving Aβ deposition [15]. Multimodal imaging studies have revealed increased drusen deposited in the outer retina of AD patients, leading to photoreceptor degeneration and outer retinal atrophy [16]. Additionally, choroidal thinning and reduced choriocapillaris flow have been observed in AD patients [17, 18], reinforcing the choroid’s potential as a biomarker for early AD detection. However, whether these choroidal and outer retinal alterations occur in SCD remains unknown, necessitating further investigation.

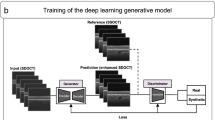

Quantifying choroidal changes has historically been challenging due to the scattering effect of retinal pigment granules. However, swept-source optical OCTA (SS-OCTA) equipped with deep learning-based automated segmentation software now enables precise delineation of choroidal boundaries and accurate three-dimensional analysis of large and medium choroidal vessels [19, 20]. This technology allows for the calculation of key metrics such as choroidal vessel volume (CVV) and choroidal vessel index (CVI), providing choroidal alterations in SCD.

In this study, we employed ultra-wide SS-OCTA to comprehensively evaluate structural and perfusion changes in the outer retina and choroid of individuals with SCD. Specifically, we assessed outer retinal and choroid thickness, choriocapillaris blood flow, and large/ medium choroidal vessel parameters. Subsequently, we compared these metrics across SCD participants with varying brain amyloid loads and explored their correlation with plasma Aβ concentration. We further detected the potential effects of APOE ε4 on the alterations of the outer retina and choroid in participants with SCD. Our findings aim to establish the choroid as a potential ocular biomarker for early detection of prodromal AD.

Materials and methods

Study design and ethics considerations

This cross-sectional study was approved by the ethics committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, and the Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Approval No. TJ-IRB20220830). A total of 102 participants were consecutively recruited from the community-based population and the Neurology Outpatient Clinic of Tongji Hospital from September 2022 to October 2024. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment.

According to the updated SCD-plus criteria proposed by Jessen et al. in 2020 [1], individuals with SCD were included if they met the following criteria: 1) Age ≥ 60 years; 2) Persistent self-reported cognitive decline (≥ 6 months); 3) Normal age- and education-adjusted performance on standardized neuropsychological tests (within ± 1 SD of normative means). 4) Availability of a collateral informant to corroborate cognitive concerns. The Normal Control (NC) group consisted of those without SCD complaints with normal cognitive screening scores [21]. NCs were selected from among the spouses, colleagues, or siblings of individuals with SCD to ensure age matching with the SCD group.

Exclusion criteria for all groups include: 1) Participants were excluded if they had a history of neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., Parkinson’s disease) or systemic severe disease affecting cognition (e.g., uncontrolled diabetes, severe renal/ hepatic dysfunction); 2) Major ophthalmological pathologies (glaucoma, AMD, retinal detachment, or spherical equivalent refractive error > −6 diopters; 3) cerebral small vessel disease (Fazekas score > 2 points on MRI; 5) Contraindications for PET imaging. The detailed flow chart is presented in Fig. 1.

Clinical data collection and neuropsychological assessments

Demographic characteristics (age, sex, education level) and medical histories were systematically recorded. A comprehensive neuropsychological battery was administered by trained psychologists, including: 1) Global cognition: Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [22], Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [23]; 2) Memory Domain: Auditory Verbal Learning Test-HuaShan version (AVLT-H) [24]; 3) Executive function: Trail Making Test Part A and Part B (TMT) [25]; 4) Visuospatial skills: Clock Drawing Test (CDT) [26]; 5) Language: the 30-item Boston Naming Test (BNT) [27].

Ocular imaging protocol

Comprehensive ophthalmological evaluation

All participants received standardized ophthalmological examinations conducted by a board-certified ophthalmologist, including 1) Medical history review: documentation of ocular pathologies, surgical interventions, and pharmacotherapy; 2) Visual function assessment: Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) quantified using decimal notation; 3) Intraocular pressure (IOP) measured via non-contact tonometry (NT-510; NIDEK Tokyo, Japan).

SS-OCTA imaging protocol

Light source: 1050 nm wavelength swept laser; Acquisition rate: 2,000,000 A-scan/sec; scan pattern: 6 × 6 mm macular cube (1024 × 1024 sampling density); signal averaging: Quadruplicated B-scans per fixation (VG200S; SVision Imaging, Henan, China).

Image acquisition and quality control

All scans were centered on the foveal avascular zone. Images underwent automated quality assessment with the following exclusion criteria: 1) Signal strength index < 6; Significant motion artifacts (vessel discontinuity ≥10% scan area); 2) Segmentation errors requiring >5% manual correction.

Quantitative image analysis

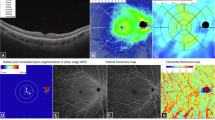

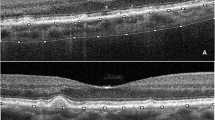

The integrated segmentation algorithm delineated retinal-choroidal boundaries as follows: 1) Outer retina: outer plexiform layer to retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) interface (Fig. 2A). 2) Choroidal thickness (ChT) was defined as the length between Bruch’s membrane and the choroid-sclera interface (Fig. 2B). The wrong segmentations were modified by a trained ophthalmologist before quantitative analysis. 3) Choriocapillaris flow area (FA) served as a quantitative measure of small choroidal vessel perfusion (Fig. 2C). 4) CVV and CVI were used to illustrate large and medium choroidal vessel perfusion (Fig. 2D). CVV was defined as the volume of the large and medium choroidal vessels. CVI was calculated by determining the ratio of the CVV relative to the volume of the entire choroid.

A The outer retinal thickness was from the base of the outer plexiform layer to the base of the retinal pigment epithelium. B The choroidal thickness was defined as the base of the Bruch membrane to the choroid-sclera interface. C Image of the choriocapillaris flow area. D Image of the large and medium choroidal vessels. E Following the ETDRS protocol, the macula was divided into three concentric rings with diameters of 1 mm (fovea), 1–3 mm (parafovea), and 3–6 mm (perifovea).

The structural and perfusion parameters were automatically calculated by a deep learning algorithm in the SS-OCTA software, following the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) protocol. With diameters of 1 mm, 1–3 mm, and 3–6 mm, three concentric rings divided the macula into the fovea, parafovea, and perifovea. (Fig. 1E).

Amyloid PET imaging

In our study, all participants underwent 18F-Florbetapir PET/CT using a Discovery MI scanner (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) at Tongji Hospital. The imaging protocol was performed as follows: intravenous injection of 18F-Florbetapir (185~370MBq; radiochemical purity > 95%). Standardized uptake time of 30–50 min post-injection. Static 10 min brain PET scan in 3D mode, with head immobilization to minimize motion artifacts. After scans, the PET images were corrected and reconstructed. Two board-certified nuclear medicine experts, who were not privy to clinical data, independently examined amyloid deposition as per the guideline [28].

Plasma amyloid analysis

Venous blood samples were collected in pre-chilled K2-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes (BD Vacutainer) and centrifuged at 1500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C within 2 h of collection. The plasma was separated and stored in a −80 °C freezer immediately until batch analysis. Quantification of Aβ 42 and Aβ 40 concentrations was performed using the ultra-sensitive single-molecule array (Simoa) Human Neurology 4-Plex E (N4PE) assay [29].

APOE genotype

APOE genotyping was carried out in the Department of Laboratory Medicine of Tongji Hospital, following the methodology previously outlined [30]. Genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood, and polymerase chain reaction was employed to determine APOE genotypes. This process involved analyzing the alleles of two single nucleotide polymorphisms at the APOE locus, specifically rs429358 and rs7412. Participants were categorized into two groups based on their genotypes: APOE ε4 carriers (ε4/ε4, ε3/ε4, and ε2/ε4) and non-carriers (ε2/ε2, ε2/ε3, and ε3/ε3).

Statistical analysis

In our study, a case-control analysis was conducted, utilizing thickness and perfusion metrics obtained via OCTA from age and sex-matched control subjects. The mean ORT was recorded as 115 ± 8 μm [31]. To detect a mean difference of 5 μm between the two groups, with a standard deviation of 8 μm, a sample size of 41 participants per group is necessary to achieve a statistical power of 0.8, assuming a significance level (alpha) of 0.05. Categorical variables were expressed as counts (percentages) and compared using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test (expected cell frequency <5), while continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data (analyzed by independent Student’s t-test) or median with interquartile range (25th–75th quartile) for non-normally distributed data (analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test). Spearman’s correlation coefficient was computed to assess the bivariate association between ORT and CVI, the FDR correction (BH method) was employed to control the type I error. Partial correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate the relationship between choriocapillaris parameters and plasma biomarkers, controlling for age and sex as covariates. All tests were two-tailed, with p < 0.05 defining statistical significance. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R 4.4.2 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 102 participants were included for OCTA scanning. Three eyes of participants with SCD were excluded, including two with AMD, and one with retinal detachment. Nine eyes of normal controls were excluded, including three with AMD, one with retinal detachment, two with high myopia, and three with vitreous opacity (Fig. 1). Among them, 57 individuals with SCD (109 eyes) and 45 normal controls (83 eyes) were qualified for further analysis. There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, BCVA, IOP, past medical history (hypertension and diabetes), educational level, and cognitive performance between the two groups (Table 1).

Comparison of the choroid and outer retina parameters between SCD and NC

The choroid and outer retina indices were measured using OCTA. Significantly higher CVI was observed in the SCD group compared to the NC group in both the fovea (p = 0.013) and parafovea (p = 0.022). In contrast, the ORT was found to be significantly thinner in SCD groups relative to the NC, as noted in the perifovea (p = 0.044) and the total regions (p = 0.035). There was no significant difference in the choriocapillaris FA, CVV, and ChT between the two groups (Fig. 3, with detailed statistical results summarized in Supplementary Table 1). These findings indicate that alterations occur in both CVI and ORT in SCD.

Correlation between outer retinal thickness and CVI in SCD

Given that the outer retina was predominantly supplied by the choroidal vasculature, the thickness of the outer retina could potentially reflect the perfusion of the choroid. CVI serves as a dependable indicator for quantifying the perfusion of large and medium choroidal vessels. Spearman correlation analyses were performed to explore the association between ORT and CVI within the SCD group. We found significantly negative associations between the ORT and CVI in the fovea (r = −0.422, FDR p < 0.001) and multiple regions (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 2), suggesting that a thinner ORT may be related to a larger CVI in SCD.

Comparison of choroid and outer retina parameters between Aβ-SCD and Aβ + SCD

To evaluate the diagnostic potential of OCTA indices for detecting Aβ deposits in SCD, these parameters were compared between SCD patients with Aβ-positive (Aβ + ) and Aβ-negative (Aβ-) status. Aβ deposition was assessed using 18F-Florbetapir PET imaging, which identified 14 Aβ+ and 16 Aβ- individuals with SCD. The Aβ + SCD group demonstrated a higher proportion of females (p = 0.046), a lower educational attainment (p = 0.024), and a prolonged completion time on the TMT-B test (p = 0.028) compared to the Aβ- group. No significant differences were observed in age, BCVA, IOP, past medical history, and other cognitive parameters between the two groups (Supplementary Table 3). A total of 31 eyes from Aβ- SCD patients and 26 eyes from Aβ + SCD patients were included in the final analysis. Compared to Aβ- SCD group, the Aβ + SCD group exhibited significantly increased choriocapillaris FA in the fovea (p = 0.040) and parafovea (p = 0.031). No significant differences were detected in the retinal thickness values or parameters related to large and medium choroidal vessel between the two groups (Fig. 5, detailed statistical results are provided in Supplementary Table 4). These findings suggest that Aβ may preferentially affect choriocapillaris perfusion without significantly altering large and medium choroidal vessel parameters in SCD.

Correlation between choriocapillaris perfusion parameter and plasma Aβ

A lower ratio of plasma Aβ 42/40 is consistent with increased brain Aβ deposition as evaluated by PET [32]. The potential association between choriocapillaris perfusion and plasma Aβ was further investigated. A number of participants declined to provide blood samples, eventually, plasma Aβ was measured in 21 NCs and 29 individuals with SCD. There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, BCVA, IOP, past medical history, educational level, and cognitive performance between the two groups (Supplementary Table 5). A partial correlation analysis was performed to evaluate the relationship between choriocapillaris FA and plasma Aβ levels. After adjusting for age and gender, a significant negative correlation was found between Aβ 42/40 and choriocapillaris FA in the perifovea (r = −0.420, p = 0.029) and the total region (r = −0.425, p = 0.027) in the SCD group. Conversely, no significant correlation was observed between choriocapillaris FA and Aβ levels in the normal control (Fig. 6, Supplementary Table 6). This indicated that an increase in choriocapillaris flow areas is associated with a lower plasma Aβ 42/40 ratio in SCD.

A Association of choriocapillaris FA in the perifovea with plasma Aβ 42/40 in participants with SCD. B Association of choriocapillaris FA in the total ETDRS circle with plasma Aβ 42/40 in participants with SCD. FA flow area, Aβ, amyloid, SCD subjective cognitive decline. r is the partial correlation coefficient, p value was adjusted for age and sex.

Effects of APOE ε4 on the outer retina and choroid in SCD

The APOE ε4 allele is associated with a heightened risk of AD [33]. To investigate its effects on the outer retinal and choroidal alterations in individuals with SCD, the factors including age, sex, BCVA, IOP, past medical history, educational level, and cognitive performance, were matched between APOE ε4 carriers (n = 13) and non-carriers (n = 21) (Supplementary Table 7). The APOE ε4 carriers exhibited a greater choriocapillaris flow area in the fovea (p = 0.031), parafovea (p = 0.001), perifovea (p = 0.001), and total ETDRS circle (p < 0.001) compared to APOE ε4 non-carriers. Moreover, the APOE ε4 carriers had increased CVV in the perifovea (p = 0.018) and total ETDRS circle (p = 0.023) relative to APOE ε4 non-carriers. There was no significant difference in the CVI, ORT, and ChT between APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers (Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 8).

Discussion

In the present study, we observed a significantly increased CVI and a reduction in the ORT among individuals with SCD. Moreover, Aβ + SCD participants exhibited a significant increase in choriocapillaris FA both in the fovea and parafovea compared to their Aβ- counterparts. Additionally, carriers of the APOE ε4 allele in the SCD cohort showed significantly higher choriocapillaris FA and CVV, suggesting the influence of the APOE ε4 allele on the choroidal perfusion. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to comprehensively characterize choroidal perfusion in SCD patients and explore its association with amyloid status in SCD. Our findings imply that both dysfunction of the ORT and altered choroidal perfusion occur in SCD, and the choriocapillaris FA may serve as a valuable biomarker for the early detection of Aβ + SCD cases.

Altered OCTA parameters in the subjective cognitive decline

Our study revealed that individuals with SCD exhibited an increased CVI in both the foveal and perifoveal regions compared to normal controls. The CVI, defined as the ratio of the CVV to the volume of the entire choroid, is a reliable metric for quantifying perfusion in large and medium choroidal vessels [34]. Robbins et al. observed decreased CVI in patients with MCI relative to controls but not those with AD [35], suggesting complicated and dynamic alterations in choroidal vasculature throughout the AD continuum. Our previous study reported that reduced retinal perfusion in the superficial vascular complex may be associated with the SCD stage [13]. In this study, the elevated CVI in SCD participants reflects enhanced large and medium choroidal vessel perfusion and a strong compensatory mechanism to maintain the blood supply to the retinal and choroidal at this stage.

Previous studies have reviewed the thinning of the inner retina thickness within the AD spectrum [36, 37], while reports on ORT alterations have been scarce and inconsistent. Kim et al. observed consistent thinning of the outer retina across all regions in 5XFAD mice [38]. In contrast, the APPNL-F/NL-F AD models exhibited an increase of ORT at different time points [39]. Empirical studies have identified correlations between ORT and cognitive function, particularly among older adults, implying that retinal changes may be linked to structural modifications within the brain [40]. A cross-sectional study indicated outer retinal thinning in the parafovea (1–3 mm) and perifovea (3–6 mm) in individuals with posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) [19]. Uchida et al. reported no significant differences in ORT in the fovea and juxtafovea (1–2 mm) between patients with amnestic MCI and AD compared to normal controls [41]. Our study demonstrated that individuals with SCD exhibited a thinner ORT compared to normal controls, particularly in the perifovea (3–6 mm), suggesting that structural changes in the outer retina occur early in the SCD stage. The more pronounced thinning of perifovea of the outer retina appears to be closely associated with the distribution of photoreceptor cells. There are two primary types of retinal photoreceptor cells in human: rods and cones. Rod cells are predominantly located in the peripheral regions of the outer retina, while the density of cone cells increases toward the macula, achieving its peak concentration at the fovea [42]. Rod cells are more susceptible to damage under ischemic conditions due to their high oxygen consumption characteristics. Compared with cone cells, rod cells exhibit more pronounced synaptic functional impairment and produce more reactive oxygen species under ischemic conditions [43, 44]. Moreover, lipid composition disparity may lead to greater susceptibility of rod cells to membrane damage and cellular death under ischemic conditions. Studies have shown that rod cell membranes contain higher levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids, particularly docosahexaenoic acid than cone cells [45]. Research has demonstrated a significant association between alterations in ORT and the aging process. In the course of normal aging, there is a general trend towards a reduction in the thickness of the outer retina, which is concomitant with the degeneration of the retinal pigment epithelium and photoreceptors [46]. Furthermore, males generally exhibit thicker ORT than females, particularly in the fovea and parafovea area [47]. African American and Asian American individuals exhibited reduced central retinal thickness in comparison to their Caucasian counterparts [48]. These findings underscore the imperative for stringent control of variables, including age, gender, and race, in the conduct of comparative studies on retinal thickness, in order to mitigate the influence of confounding factors on the results. The outer retina, located in the avascular zone, mainly obtains nutrients through diffusion from the choroidal microvasculature. The thinning of the outer retina might reflect alterations in choroidal perfusion at this stage. In our study, a significant negative correlation was observed between the CVI and ORT during the SCD stage. The dilation of choroidal vasculature, characterized by increased permeability, may lead to the degeneration and atrophy of photoreceptors, resulting in subsequent thinning of the outer retina. Furthermore, curcumin angiography has demonstrated that retinal amyloid plaques accumulate in the photoreceptor layer in a transgenic mouse model of AD [49]. A recent study has initially reported the presence and distribution of Aβ in the ocular and periocular regions of AD post-mortem eye tissues, including the retina, optic nerve, choroid, and periorbital lymphatic vessels, highlighted the transport of Aβ from the brain to the eye via the optic nerve through CSF as a key factor in AD retinopathy [50]. The impairment of the ocular glymphatic clearance system and the perivenous lymphatic clearance pathway may lead to the prolonged accumulation of brain-derived Aβ within the ocular environment. This accumulation of ocular Aβ has the potential to activate glial cells, resulting in ocular degeneration [51]. Furthermore, the accumulation of Aβ triggers the expression of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells. These inflammatory mediators facilitate inflammatory responses via the NF-κB signaling pathway [52]. Consequently, Aβ accumulation and the ensuing inflammatory responses may contribute to neurotoxicity, photoreceptor loss, and ultimately, the thinning of the outer retina.

Increased choriocapillaris flow area and amyloid accumulation

According to the 2024 biological definition of AD by the Alzheimer’s Association, those with evidence of Aβ deposition are considered within the AD continuum [53]. In this study, we further investigate the difference in choroidal structure and vasculature among SCD participants based on their amyloid deposition status determined by amyloid PET. Our results demonstrated that Aβ + SCD participants exhibited a significantly increased choriocapillaris FA compared to Aβ- SCD participants. Our findings are consistent with those of van de Kreeke JA et al., who reported higher retinal vessel density in individuals with preclinical AD [54]. Another prospective study also supported these findings by demonstrating an increasing trend in retinal vessel density during the follow-up period in the participants who were Aβ positive at baseline [55]. A plausible explanation for our findings may be attributed to the heightened inflammatory response of the choroid during the early stages of amyloid accumulation, as occurs in synchrony within the brain [56]. This inflammatory status may lead to an increased blood supply to the choriocapillaris to meet adequate perfusion and metabolic demands during this early phase [54]. As the disease progresses, persistent inflammation and Aβ accumulation may lead to additional damage to the choroidal vasculature, ultimately reducing the flow area. This may explain the observed decrease in choriocapillaris FA in AD patients [57]. In this study, the Aβ- SCD group comprised a higher proportion of females compared to the Aβ + SCD group. To investigate the potential influence of sex on choriocapillaris FA, we included sex-specific subgroup analyses. Our analyses revealed no statistically significant differences in choriocapillaris flow area between the two groups (Supplementary Table 9). These findings are consistent with a previous study, which also reported no significant sex differences in retinal and choroidal perfusion in both Alzheimer’s disease and control cohorts [58].

Compared to PET, peripheral blood testing is more practical and cost-effective. The development of ultrasensitive detection methods has made plasma Aβ a promising alternative for screening individuals with AD pathology [32]. Our study revealed a negative correlation between the choriocapillaris FA and the peripheral blood Aβ 42/40 ratio during the SCD stage, which was not observed in the normal controls. This provided new evidence of a possible association between choriocapillaris perfusion and AD-related pathological change in the SCD stage. The choriocapillaris FA may serve as a valuable biomarker for the early detection of high-risk individuals in the preclinical stage.

Effects of APOE ε4 on the outer retina and choroid in SCD

The APOE ε4 allele may potentially influence choroidal perfusion. A recent study reported that APOE ε4 carriers in participants with PCA, a visual variant of AD, had significantly increased choriocapillaris vascular density and CVI [19]. Our study further revealed that among SCD participants, APOE ε4 carriers had significantly higher choriocapillaris FA and CVV compared to non-carriers. According to our knowledge, this is the first research to clarify the association between the APOE ε4 allele and alterations in the outer retinal and choroidal microvasculature and structure in SCD participants. Prior studies have examined how the inner retinal microvasculature and structure differ between APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers with normal cognitive function. Research by Ma et al. demonstrated that APOE ε4 allele carriers had lower central subfield thickness, perfusion density, and peripapillary capillary flux index than non-carriers [59]. Sheriff and colleagues also observed APOE ε4 carriers exhibited reduced thickness in the retinal nerve fiber layer and a smaller foveal avascular zone area [60]. Moreover, in AD patients, a reduced macular vascular density in the superficial retinal capillary plexus has been observed in the APOE ε4 carriers [61]. The APOE ε4 allele is acknowledged as the primary genetic risk factor for AD, associated with both neuronal and vascular impairments [33]. Recent research has suggested that APOE ε4 is involved in angiogenesis and synaptic pathology in the retina and choroid, with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) potentially playing a regulatory role [62]. In APOE ε4 mice, reduced VEGF levels and increased activation of inflammatory response markers were more prominent, potentially leading to increased choroidal neovascularization. Aβ is known to influence the oligomerization, aggregation, and neurotoxicity of APOE ε4 [63]. APOE ε4 is capable of forming SDS-stable oligomers, which may represent aggregated states that become more prevalent upon incubation with Aβ42. In vitro co-incubation experiments using human neuronal cells demonstrate that Aβ42 enhances the formation of SDS-stable APOE ε4 oligomers and augments the cytotoxic effects of APOE ε4 [64]. Moreover, APOE ε4 has been demonstrated to enhance the cellular uptake of Aβ, consequently promoting its aggregation and subsequent neurotoxic effects [65]. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), the primary APOE receptor, is abundantly expressed in vascular mural cells (pericytes and smooth muscle cells) and brain [66]. Research indicates that APOE ε4 exacerbates Aβ pathology through its interactions with LRP1 [67]. Moreover, APOE ε4 diminishes the capacity for Aβ clearance by inhibiting autophagy pathways, thereby further aggravating Aβ deposition [68]. A univariate association was observed between APOE ε4 carriership and increased amyloid pathology in SCD participants [69]. Intriguingly, our study demonstrated that choroidal perfusion alterations in APOE ε4 carriers were consistent with those in Aβ + SCD participants, suggesting that the effect of APOE ε4 on choroidal perfusion alterations may be mediated by Aβ accumulation. Future studies with detailed APOE genetic profiles may further elucidate the impact of APOE ε4 on choroidal perfusion alterations.

Limitation

The current study has several limitations. Firstly, it is a cross-sectional study, a longitudinal study is imperative to comprehensively track the dynamic variation in the outer retina and choroid throughout the disease progression. Second, the sample size of participants who underwent Aβ-PET and peripheral blood Aβ testing was relatively small. Further investigation with a larger sample size is thus advisable to boost statistical power and elucidate the association between choroidal changes and AD-related pathology. Thirdly, since plasma phosphorylated tau 217 (p-tau 217) is a more effective predictor of amyloid and tau burden, future studies ought to include plasma p-tau 217 measurements to explore the potential relationship between p-tau 217 and ocular alterations.

Conclusions

The current study initially characterized choroidal perfusion among individuals with SCD. Our results provide strong and convincing insights regarding the association between amyloid pathology and changes in the choriocapillaris flow area in SCD, thereby enriching the ocular indices applicable for AD screening. Considering the non-invasive and cost-effective attributes of OCTA, ocular structure and microvascular indices may potentially serve as valuable biomarkers for identifying high-risk SCD prone to progression to AD.

Data availability

The original datasets in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Jessen F, Amariglio RE, Buckley RF, van der Flier WM, Han Y, Molinuevo JL, et al. The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:271–8.

Jack CR Jr., Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:535–62.

Perneczky R, Dom G, Chan A, Falkai P, Bassetti C. Anti-amyloid antibody treatments for alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2024;31:e16049.

Shao K, Hu X, Kleineidam L, Stark M, Altenstein S, Amthauer H, et al. Amyloid and SCD jointly predict cognitive decline across Chinese and German cohorts. Alzheimers Dement. 2024;20:5926–39.

Giudici KV, de Souto Barreto P, Guyonnet S, Li Y, Bateman RJ, Vellas B, et al. Assessment of plasma amyloid-beta42/40 and cognitive decline among community-dwelling older adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2028634.

Gonzalez-Ortiz F, Kac PR, Brum WS, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Karikari TK. Plasma phospho-tau in Alzheimer’s disease: towards diagnostic and therapeutic trial applications. Mol Neurodegener. 2023;18:18.

Koronyo Y, Biggs D, Barron E, Boyer DS, Pearlman JA, Au WJ, et al. Retinal amyloid pathology and proof-of-concept imaging trial in alzheimer’s disease. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e93621.

Lemmens S, Van Craenendonck T, Van Eijgen J, De Groef L, Bruffaerts R, de Jesus DA, et al. Combination of snapshot hyperspectral retinal imaging and optical coherence tomography to identify alzheimer’s disease patients. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12:144.

Ngolab J, Donohue M, Belsha A, Salazar J, Cohen P, Jaiswal S, et al. Feasibility study for detection of retinal amyloid in clinical trials: the anti-amyloid treatment in asymptomatic alzheimer’s disease (A4) trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;13:e12199.

Hui J, Zhao Y, Yu S, Liu J, Chiu K, Wang Y. Detection of retinal changes with optical coherence tomography angiography in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease patients: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0255362.

Rifai OM, McGrory S, Robbins CB, Grewal DS, Liu A, Fekrat S, et al. The application of optical coherence tomography angiography in alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;13:e12149.

Yeh TC, Kuo CT, Chou YB. Retinal microvascular changes in mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:860759.

Gao R, Luo H, Yan S, Ba L, Peng S, Bu B, et al. Retina as a potential biomarker for the early stage of alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2024;11:2583–96.

Nickla DL, Wallman J. The multifunctional choroid. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29:144–68.

Ohno-Matsui K. Parallel findings in age-related macular degeneration and alzheimer’s disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2011;30:217–38.

Fleckenstein M, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Chakravarthy U. Age-related macular degeneration: a review. JAMA. 2024;331:147–57.

Cunha JP, Proenca R, Dias-Santos A, Melancia D, Almeida R, Aguas H, et al. Choroidal thinning: alzheimer’s disease and aging. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;8:11–7.

Di Pippo M, Cipollini V, Giubilei F, Scuderi G, Abdolrahimzadeh S. Retinal and choriocapillaris vascular changes in early alzheimer disease patients using optical coherence tomography angiography. J Neuroophthalmol. 2024;44:184–9.

Gao Y, Wang R, Mou K, Zhang Y, Xu H, Liu Y, et al. Association of outer retinal and choroidal alterations with neuroimaging and clinical features in posterior cortical atrophy. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2024;16:187.

Luo H, Sun J, Chen L, Ke D, Zhong Z, Cheng X, et al. Compartmental analysis of three-dimensional choroidal vascularity and thickness of myopic eyes in young adults using SS-OCTA. Front Physiol. 2022;13:916323.

Sheng C, Lin L, Lin H, Wang X, Han Y, Liu SL. Altered gut microbiota in adults with subjective cognitive decline: the SILCODE study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;82:513–26.

Li H, Jia J, Yang Z. Mini-mental state examination in elderly chinese: a population-based normative study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;53:487–96.

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–9.

Guo QH, Zhao QH, Chen MR, Ding D, Hong Z. A comparison study of mild cognitive impairment with 3 memory tests among Chinese individuals. Alzheimer Dis Associated Disord. 2009;23:253–9.

Rabinovici GD, Stephens ML, Possin KL. Executive dysfunction. Continuum. 2015;21:646–59.

Agrell B, Dehlin O. The clock-drawing test. 1998 Age Ageing. 2012;41(Suppl 3):iii41–5.

Devora PV, O’Mahar K, Karboski SM, Benge JF, Hilsabeck RC. Correspondence of the boston naming test and multilingual naming test in identifying naming impairments in a geriatric cognitive disorders clinic. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2022;31:1–7.

Lundeen TF, Seibyl JP, Covington MF, Eshghi N, Kuo PH. Signs and artifacts in amyloid PET. Radiographics. 2018;38:2123–33.

Wilson DH, Rissin DM, Kan CW, Fournier DR, Piech T, Campbell TG, et al. The simoa HD-1 analyzer: a novel fully automated digital immunoassay analyzer with single-molecule sensitivity and multiplexing. Jala-J Lab Autom. 2016;21:533–47.

Ye X, Li G, Liu X, Song G, Jia Y, Wu C, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype predicts subarachnoid extension in spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:1992–9.

Loduca AL, Zhang C, Zelkha R, Shahidi M. Thickness mapping of retinal layers by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150:849–55.

Blennow K, Hansson O. [Blood biomarkers open a window to brain pathophysiology in alzheimer’s disease]. Lakartidningen. 2024;121:23150.

van der Flier WM, Schoonenboom SN, Pijnenburg YA, Fox NC, Scheltens P. The effect of APOE genotype on clinical phenotype in alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:526–7.

Zhang Y, Yang L, Gao Y, Zhang D, Tao Y, Xu H, et al. Choroid and choriocapillaris changes in early-stage Parkinson’s disease: a swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography-based cross-sectional study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2022;14:116.

Robbins CB, Grewal DS, Thompson AC, Powers JH, Soundararajan S, Koo HY, et al. Choroidal structural analysis in alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment, and cognitively healthy controls. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;223:359–67.

Costanzo E, Lengyel I, Parravano M, Biagini I, Veldsman M, Badhwar A, et al. Ocular biomarkers for alzheimer disease dementia: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023;141:84–91.

Ge YJ, Xu W, Ou YN, Qu Y, Ma YH, Huang YY, et al. Retinal biomarkers in alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;69:101361.

Kim TH, Son T, Klatt D, Yao X. Concurrent OCT and OCT angiography of retinal neurovascular degeneration in the 5XFAD alzheimer’s disease mice. Neurophotonics. 2021;8:035002.

Sanchez-Puebla L, Lopez-Cuenca I, Salobrar-Garcia E, Gonzalez-Jimenez M, Arias-Vazquez A, Matamoros JA, et al. Retinal vascular and structural changes in the murine alzheimer’s APP(NL-F/NL-F) model from 6–20 months. Biomolecules. 2024;14:828.

Owsley C, McGwin G Jr., Swain TA, Clark ME, Thomas TN, Goerdt L, et al. Outer retinal thickness is associated with cognitive function in normal aging to intermediate age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024;65:16.

Uchida A, Pillai JA, Bermel R, Bonner-Jackson A, Rae-Grant A, Fernandez H, et al. Outer retinal assessment using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in patients with alzheimer’s and parkinson’s disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:2768–77.

Hanazono G, Tsunoda K, Kazato Y, Suzuki W, Tanifuji M. Functional topography of rod and cone photoreceptors in macaque retina determined by retinal densitometry. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 2012;53:2796–803.

Bhatt L, Groeger G, McDermott K, Cotter TG. Rod and cone photoreceptor cells produce ROS in response to stress in a live retinal explant system. Mol Vis. 2010;16:283–93.

Shen YM, Luo X, Liu SL, Shen Y, Nawy S, Shen Y. Rod bipolar cells dysfunction occurs before ganglion cells loss in excitotoxin-damaged mouse retina. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:905.

Verra DM, Spinnhirny P, Sandu C, Gregoire S, Acar N, Berdeaux O, et al. Intrinsic differences in rod and cone membrane composition: implications for cone degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022;260:3131–48.

Piskova T, Kozyrina AN, Di Russo J. Mechanobiological implications of age-related remodelling in the outer retina. Biomater Adv. 2023;147:213343.

Ghassemi F, Karimi M, Salari F, Bayat K. Exploring the impact of age and gender on retinal and choroidal thickness and vascular densities: a comprehensive analysis. Int J Retin Vitreous. 2025;11:38.

Wagner-Schuman M, Dubis AM, Nordgren RN, Lei Y, Odell D, Chiao H, et al. Race- and sex-related differences in retinal thickness and foveal pit morphology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:625–34.

Chibhabha F, Yang Y, Ying K, Jia F, Zhang Q, Ullah S, et al. Non-invasive optical imaging of retinal Abeta plaques using curcumin loaded polymeric micelles in APP(swe)/PS1(DeltaE9) transgenic mice for the diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8:7438–52.

Cao Q, Yang S, Wang X, Sun H, Chen W, Wang Y, et al. Transport of beta-amyloid from brain to eye causes retinal degeneration in alzheimer’s disease. J Exp Med. 2024;221:e20240386.

Simons ES, Smith MA, Dengler-Crish CM, Crish SD. Retinal ganglion cell loss and gliosis in the retinofugal projection following intravitreal exposure to amyloid-beta. Neurobiol Dis. 2021;147:105146.

Varinthra P, Huang SP, Chompoopong S, Wen ZH, Liu IY. 4-(Phenylsulfanyl) butan-2-one attenuates the inflammatory response induced by amyloid-beta oligomers in retinal pigment epithelium cells. Mar Drugs. 2020;19:1.

Jack CR Jr., Andrews JS, Beach TG, Buracchio T, Dunn B, Graf A, et al. Revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of alzheimer’s disease: alzheimer’s association workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2024;20:5143–69.

van de Kreeke JA, Nguyen HT, Konijnenberg E, Tomassen J, den Braber A, Ten Kate M, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography in preclinical alzheimer’s disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104:157–61.

Curro KR, van Nispen RMA, den Braber A, van de Giessen EM, van de Kreeke JA, Tan HS, et al. Longitudinal assessment of retinal microvasculature in preclinical alzheimer’s disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024;65:2.

McGeer PL, McGeer EG. The amyloid cascade-inflammatory hypothesis of alzheimer disease: implications for therapy. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:479–97.

Kwapong WR, Tang F, Liu P, Zhang Z, Cao L, Feng Z, et al. Choriocapillaris reduction accurately discriminates against early-onset alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2024;20:4185–98.

Mirzania D, Thompson AC, Robbins CB, Soundararajan S, Lee JM, Agrawal R, et al. Retinal and choroidal changes in men compared with women with alzheimer’s disease: a case-control study. Ophthalmol Sci. 2022;2:100098.

Ma JP, Robbins CB, Lee JM, Soundararajan S, Stinnett SS, Agrawal R, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the retina and choroid in cognitively normal individuals at higher genetic risk of alzheimer disease. Ophthalmol Retin. 2022;6:607–19.

Sheriff S, Shen T, Saks D, Schultz A, Francis H, Wen W, et al. The association of APOE epsilon4 allele with retinal layer thickness and microvasculature in older adults: optic nerve decline and cognitive change study. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6219.

Wang X, Wang Y, Liu H, Zhu X, Hao X, Zhu Y, et al. Macular microvascular density as a diagnostic biomarker for alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;90:139–49.

Antes R, Salomon-Zimri S, Beck SC, Garcia Garrido M, Livnat T, Maharshak I, et al. VEGF mediates ApoE4-induced neovascularization and synaptic pathology in the choroid and retina. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2015;12:323–34.

Loch RA, Wang H, Peralvarez-Marin A, Berger P, Nielsen H, Chroni A, et al. Cross interactions between apolipoprotein E and amyloid proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023;21:1189–204.

Dafnis I, Argyri L, Chroni A. Amyloid-peptide beta 42 Enhances the Oligomerization and Neurotoxicity of apoE4: the C-terminal residues Leu279, Lys282 and Gln284 modulate the structural and functional properties of apoE4. Neuroscience. 2018;394:144–55.

Riad A, Lengyel-Zhand Z, Zeng C, Weng CC, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, et al. The sigma-2 receptor/TMEM97, PGRMC1, and LDL receptor complex are responsible for the cellular uptake of abeta42 and its protein aggregates. Mol Neurobiol. 2020;57:3803–13.

Martiskainen H, Haapasalo A, Kurkinen KMA, Pihlajamäki J, Soininen H, Hiltunen M. Targeting ApoE4/ApoE receptor LRP1 in alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Ther Tar. 2013;17:781–94.

Tachibana M, Holm ML, Liu CC, Shinohara M, Aikawa T, Oue H, et al. APOE4-mediated amyloid-beta pathology depends on its neuronal receptor LRP1. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:1272–7.

Bassal R, Rivkin-Natan M, Rabinovich A, Michaelson DM, Frenkel D, Pinkas-Kramarski R. impairs autophagy and Aβ clearance by microglial cells. Inflamm Res. 2025;74:61.

Janssen O, Jansen WJ, Vos SJB, Boada M, Parnetti L, Gabryelewicz T, et al. Characteristics of subjective cognitive decline associated with amyloid positivity. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18:1832–45.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the participants in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research and Innovation Team Project for Scientific Breakthroughs at Shanxi Bethune Hospital (2024AOXIANG05), the National Natural Science Fund of China (82401746), and the National Natural Science Fund of China (82471103).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: LB, XFS, and MZ; Drafting of the original manuscript: RG; Revising the manuscript: LB and MZ; Acquisition and analysis of data: RG, YSR, SYC, ZXG, and BTB; Curation and visualization of data: RG and LB; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, and Huazhong University of Science and Technology (TJ-IRB20220830). Written informed Consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, R., Rao, S., Cheng, S. et al. Assessing outer retinal and choroidal changes in scd: potential for high-risk screening using SS-OCTA. Transl Psychiatry 16, 46 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03781-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03781-x