Abstract

Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have gender differences in many aspects, including suicidal ideation (SI) and grey matter volume (GMV). The relationship between GMV of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and SI in patients with MDD is unknown, especially whether there is gender difference in this relationship. The purpose of this study was to explore gender differences in SI, GMV of the ACC and their relationship in patients with MDD in China, which has not been reported yet. As part of the REST-meta-MDD consortium, 246 patients with MDD and 235 healthy controls were recruited, including 123 MDD patients with SI and 123 MDD patients without SI. All participants underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans. The 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) was used to assess depressive symptoms. Male MDD patients with SI had a longer disease duration than female patients with SI, whereas male MDD patients without SI had a lower rate of medication use than female MDD patients without SI (all p < 0.05). HAMD was significantly higher only in male MDD patients with SI than in male MDD patients without SI (p < 0.01). In the male SI group, the GMV of the right ACC was greater than in the female SI group, and in female MDD patients only, the GMV of the bilateral ACC was significantly greater in the SI group than in the non-SI group (all p < 0.001). In both male and female MDD patients, SI was positively correlated with HAMD, whereas in female MDD patients, SI was positively correlated with GMV of the ACC, which was confirmed in the subsequent regression equation. Our findings suggest that there are gender differences in SI, GMV of the ACC, and the association between them in patients with MDD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common mental disorder with clinical manifestations of depressed mood, loss of appetite, pessimism, and loss of interest that lasts for at least 2 weeks, and some patients even engage in suicidal behaviors [1,2,3]. The lifetime prevalence rate of MDD is 19% globally and 3.4% in mainland China [4,5,6]. Without effective treatment, patients with MDD are at a significantly increased risk of suicide [3, 7]. The prevalence of suicidal ideation (SI) in Chinese patients with MDD is as high as 53.1%, which is considered a serious problem for MDD patients [6]. Therefore, identifying risk factors for SI in MDD patients is crucial for successful screening and suicide prevention. Studies have identified a range of risk factors for suicide in patients with MDD, including gender, education, substance dependence, unemployment, clinical characteristics, previous history of suicide, younger age of onset, dysglycaemia and lipid levels [2, 3, 8,9,10]. However, the neural mechanisms behind these risk factors remain obscure.

A large number of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in patients with MDD have shown that limbic system regions, particularly the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), are altered during the onset, progression, remission, and relapse of depression [11,12,13,14,15], For example, numerous studies have found that the ACC volume is reduced in patients with MDD [16,17,18], and that the ACC is a ‘pre-preoptic area’ of the affective circuitry‘, which plays an important role in emotion regulation, attention, motivation and information processing [14, 19,20,21,22]. Studies have found that abnormalities in ACC are associated with SI [23]. Reduced grey matter volume (GMV) of the ACC has also been found in patients with psychiatric disorders who have attempted suicide [24]. The GMV of the ACC may be a sensitive biomarker in patients with MDD, and structural abnormalities in this brain region may be associated with the onset and development of SI [15, 25]. However, the relationship between SI and ACC GMV in patients with MDD remains inconclusive.

In patients with MDD, SI deepens with the severity of depressive symptoms, and there are gender differences in this correlation [3, 26, 27]. Females are more likely than males to develop MDD, a state that begins in adolescence and continues through menopause with fluctuating estrogen levels [28,29,30,31]. Similarly, SI is much higher in female patients with MDD than in male patients with MDD [32]. In addition, gender differences in SI show cross-cultural differences, which may be related to ethnic and cultural differences [33, 34]. In Western countries, suicide rates among women are much lower than among men [33]. However, suicide studies in China have found that women have a higher risk of suicide than men [35,36,37]. On the other hand, several studies have found that ACC abnormalities in patients with MDD are associated with depressive symptoms and that there are gender differences in this association [14, 38, 39]. One study showed that patients with higher self-reported severity of depressive symptoms had reduced right ACC volume, and this association was only significant in men [14]. However, gender differences in the relationship between the GMV of the ACC and SI in patients with MDD remain unknown.

Numerous studies have shown that SI in patients with MDD corelated with neurobiological markers, particularly manifested as significant alterations in the structure of the frontal- limbic circuitry [40,41,42,43]. In MDD patients with SI, males exhibit increased GMV in the left cerebellum, while females primarily show GMV reduction in the left lingual gyrus and dorsomedial prefrontal gyrus [44]. Additionally, males demonstrate greater cortical thickness in the right lingual gyrus but reduced right occipital lobe and right pericalcarine cortical volume [43]. However, studies investigating gender-specific brain structural differences in MDD patients with SI [43]. To date, no clinically significant imaging biomarkers or diagnostically valuable predictors have been identified [45]. Existing findings show inconsistence, potentially due to insufficient statistical power in small-sample studies, which may yield false-positive results [46, 47]; differences in preprocessing procedures may lead to inconsistent results [48]; and physiological confounders such as head movement may also interfere with analysis results [49]. The REST-meta-MDD project integrated resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging data from 25 research cohorts, including 1300 patients with MDD and 1128 healthy controls [50]. This project used a unified standardized preprocessing process for all subject data to reduce heterogeneity caused by methodological differences [50, 51]. The Friston-24 model for head motion correction was also utilized [52]. By integrating cross-center data, the project improved statistical power while minimizing the impact of analytical strategy heterogeneity on results [50].

The main objectives of this study were to investigate whether there would be gender differences in 1) demographic and clinical characteristics of MDD patients with SI; 2) the GMV of the ACC in MDD patients with SI; and 3) the relationship between the GMV of the ACC and SI in Chinese Han patients with MDD. We hypothesized that among MDD patients, there would be gender differences in SI patients with respect to demographics, clinical characteristics and ACC GMV, and also in relationship between the GMV of the ACC and SI. To the best of our knowledge, there are no similar studies available.

Methods

Participants

As part of the REST-meta-MDD consortium, this study involved 1300 patients diagnosed with MDD and 1128 healthy controls (HC) [45, 53, 54]. All participants were recruited from 18 Chinese consortium member hospitals with the same inclusion and exclusion criteria and provided written informed consent prior to study participation. Initial study approval was obtained from the local institutional review boards. The Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, approved the sharing of data in a de-identified and anonymous manner. Basic information about all patients was recorded, including diagnosis, disease duration, gender, age, education, and the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD).

In this study, a total of 88 patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and 38 healthy controls (HC) were excluded from the analysis because they did not meet the following criteria. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age 18 ~ 65 years; (2) more than 5 years of education; (3) diagnosis of MDD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) or the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10); and (4) 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) total score ≥ 8 at the time of MRI scanning.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with late-onset depression or patients in remission; (2) Incomplete demographic data (e.g. missing gender, age, or education records); (3) poor-quality imaging data (including spatial standardization failure); (4) Group mask coverage < 90% or mean frame displacement (mean FD) > 0.2; (5) Participants from research centers with < 10 samples [45].

We matched the patients with and without SI groups according to age and gender. The MDD patients were also matched with HC patients in terms of age and gender. This study finally included 235 HC and 246 MDD patients, including 123 MDD patients with SI and 123 patients without SI.

Clinical measures

The severity of depression in MDD patients was assessed using the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) [55]. The scale consists of 17 items, with 8 items scored on a 0-4 point scale (0 indicating none, 4 indicating severe), and the remaining 9 items scored on a 0-2 point scale (0 indicating none, 2 indicating severe). The total score of the HAMD is used to determine the presence and severity of depression. Studies have shown that the Chinese version of this scale has good reliability and validity [2, 56, 57].

The suicide item (item 3) of the HAMD measured SI. This item uses a 4-point scale, where 0 = absent, 1 = feels that life is not worth living, 2 = hopes or thinks about death, 3 = has suicidal thoughts, and 4 = has suicide attempts suicide. In this study, individuals scoring of 3 and 4 were categorized as SI, and those scoring 0, 1, and 2 were categorized as non-SI [58,59,60].

Image acquisition, preprocessing, and quality control

Each patient underwent an MRI brain scan and T1 structure-weighted images were acquired [45]. The MRI images were processed using DPARSF software, SPM 8 and VBM 8 toolbox (http://dbm.neuro.unijena.de/vb) [51, 61]. T1 images were normalized using template space and then segmented into grey matter (GM), white matter (WM) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Individual native spaces were converted to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using the Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration Through Exponential Lie (DARTEL) algebraic tool [62]. Once preprocessing was complete, quality checks were performed using the modules ‘Display One Slice of All Images’ and ‘Check Sample Homogeneity Using Covariance’. Images were normalized using an 8 mm full width at half maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel.

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables were assessed for normal distribution by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p > 0.05). Homogeneity of variance was evaluated by Levene’s test (p > 0.05). The assumption of sphericity was assessed by the Mauchly test (P > 0.05). Continuous variables were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test. SI (SI vs. non-SI), diagnosis (patients vs. healthy controls), sex (male vs. female), SI-gender interaction, and diagnosis-gender interaction were used as independent variables to explore the gender differences in demographic and clinical variables.

GMV of the ACC was analyzed using DPABI Toolbox 7.0 [51] and two-sample t-tests were used with age, education, first episode, medication status, disease duration, HAMD and head movement as covariates to determine the differences between patients with MDD and HC, or between MDD patients with and without SI. A two-sample t-test was conducted for MDD patients with SI, with sex as the independent variable, GMV of the ACC as the dependent variable, and age, education, first episode, medication status, disease duration, HAMD, and head movement as covariates. Similarly, two-sample t-tests were performed for male and female MDD patients with SI as the independent variable, GMV of the ACC as the dependent variable, and age, education, first onset, medication status, disease duration, HAMD, and head movement as covariates. Masks were regions of interest for the ACC as defined by the Harvard-Oxford Atlas [63,64,65]. In addition, we adjusted for multiple testing using 1000 permutations and a threshold-free clustering enhancement (TFCE) correction.

We used Pearson’s correlation coefficient to assess the relationship between the variables, with 1000 permutations and a TFCE correction for the relationship between the GMV of the ACC and other variables. GMV under the clusters with significant correlation and GMV of the whole ACC were extracted. Logistic regression was used to analyze the factors influencing SI in male and female MDD patients, respectively. Multiple linear regression was used to analyze the factors influencing GMV of the ACC in male and female MDD patients. In addition, logistic regression was analyzed for MDD patients with SI using gender as the dependent variable. Correlations between GMV of the ACC and other variables were also analyzed in male and female MDD patients with and without SI. Similarly, multiple linear regression models were used to analyze whether the relevant factors entered the regression equation.

All statistical analyses were calculated using R version 4.3.1 (http://cran.r-project.org). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. We set the p-value at a two-tailed significance level ≤ 0.05.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Demographic and clinical data for all subjects are shown in Table 1. There was a significant difference in education between patients with MDD and HCs (P < 0.001). There were also significant differences in HAMD (P < 0.001) and head movements (P < 0.05) between MDD patients with and without SI.

In patients with MDD, medication status and disease duration were statistically significant in the SI × gender interaction (both p < 0.05). Further analyses revealed that among MDD patients with SI, males had significantly longer disease duration than females (F = 4.009, df = 1121, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.032). Among MDD patients without SI, the proportion of female medication users was high than that of males (χ2 = 4.211, df = 1, p < 0.05, OR = 3.22, 95% CI: 1.13–9.14). These factors were controlled for as covariates in subsequent analyses.

In male MDD patients, HAMD was significantly higher in patients with SI than those without SI (F = 10.21, df = 1,76, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.118). In female MDD patients, no significant differences were found between the SI and non-SI groups in terms of demographic data and clinical indicators.

Gender differences in GMV of the ACC in MDD patients with and without SI

In MDD patients, only the two clusters with a cluster size of 1 voxel located on the right side of the ACC had significantly smaller GMV than HCs (cluster 1: Cluster size=1, Peak voxel X = 6, Y = 18, Z = 21, t = 4.387; cluster 2: Cluster size=1, Peak voxel X = 6, Y = 15, Z = 22.5, t = 6.201). GMV of the bilateral ACC was higher in MDD patients with SI than in MDD patients without SI (cluster 1: Cluster size=653, Peak voxel X = 1.5, Y = 15, Z = 28.5, t = 6.154; cluster 2: Cluster size=270, Peak voxel X = -6, Y = 18, Z = 33, t = 5.322, cluster 3: Cluster size=14, Peak voxel X = -1.5, Y = 34.5, Z = 13.5, t = 6.201). These results remained significant when covariates such as age and education were added. All results passed 1000 permutations with TFCE correction.

Furthermore, we compared GMV of the ACC in male and female MDD patients with SI and found that the GMV of the right-sided ACC was greater in males than in females, reaching statistical significance (cluster 1: Cluster size=883, Peak voxel X = 1.5, Y = -6, Z = 36, t = 4.803; cluster 2: Cluster size=8, Peak voxel X = -1.5, Y = -15, Z = 31.5, t = 4.393, Fig. 1). After adding age, education, first episode, medication status, disease duration, HAMD, and head motion as covariates, these results remained significant and passed 1000 permutations with TFCE correction (cluster 1: Cluster size=916, Peak voxel X = 1.5, Y = -6, Z = 36, t = 5.217; cluster 2: Cluster size=67, Peak voxel X = -1.5, Y = -15, Z = 31.5, t = 5.181, Figure S1).

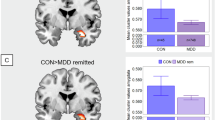

In patients with MDD, a two-way ANOVA examining the SI × gender interaction on GMV of the whole ACC revealed significant main effects of both SI (F = 9.79, df = 1242, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.034) and gender (F = 33.09, df = 1242, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.116). In addition, we examined GMV of the ACC in males and females in MDD patients with and without SI, respectively. In male MDD patients, no significant difference in GMV of the ACC was found between the SI group and the non-SI group. In female MDD patients, bilateral ACC GMV was significantly greater in the SI group than in the non-SI group (cluster 1: Cluster size=546, Peak voxel X = 3, Y = 33, Z = 15, t = 6.179; cluster 2: Cluster size=394, Peak voxel X = -6, Y = 15, Z = 34.5, t = 4.836, Fig. 2). These differences remained significant after adding age, education, first episode, medication status, disease duration, HAMD, and head motion as covariates (cluster 1: Cluster size=514, Peak voxel X = 3, Y = 33, Z = 15, t = 6.224; cluster 2: Cluster size=426, Peak voxel X = - 6, Y = 15, Z = 34.5, t = 4.750, Figure S2). All results passed 1000 permutations with TFCE correction.

Gender differences in the relationships between ACC of the GMV and SI in MDD patients

In male MDD patients, there was a positive correlation between HAMD (r = 0.344, p < 0.01, Fig. 3a) and SI. Logistic regression results showed that HAMD (t = 3.005, p < 0.01) and disease duration (t = 2.589, p < 0.01) were significantly associated with SI. Multivariate regression analysis showed that medication status (t = 3.183, p < 0.001) and age (t = -2.578, p < 0.05) were associated GMV of the whole ACC.

A Significant positive correlations of SI and HAMD (p < 0.01) in male MDD individuals. B Significant positive correlations of SI and HAMD (p < 0.05) in female MDD individuals. C Significant positive correlations of SI and GMV of the whole ACC (p < 0.01) in female MDD individuals. Half-violin plots show the distribution of the data, overlaid with half-box plots indicating the median and interquartile range (25%–75%), with whiskers extending to 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR).

In female MDD patients, SI was positively correlated with HAMD (r = 0.192, p < 0.05, Fig. 3b) and GMV of the whole ACC (r = 0.232, p < 0.01, Fig. 3c). Logistic regression results showed that HAMD (t = 2.442, p < 0.05), GMV of the whole ACC (t = 2.945, p < 0.01) and medication status (t = -2.057, p < 0.05) were significantly associated with SI. Multivariate regression analysis showed that first episode (t = 2.210, p < 0.05), age (t = -3.058, p < 0.01) and SI (t = 3.138, p < 0.01) were associated with GMV of the whole ACC. In addition, a logistic regression analysis was performed for MDD patients with SI, using gender as the dependent variable. The results showed that GMV of the whole ACC (t = -2.695, p < 0.01) was significantly associated with gender.

Furthermore, correlation between GMV of the ACC and demographic and clinical variables were analyzed in male and female MDD patients with and without SI, respectively. The results showed that GMV of the right ACC was associated with education only in female MDD patients with SI (Cluster size=11, Peak voxel X = 3, Y = -6, Z = 43.5, r = -0.429, 1000 permutations with TFCE correction; Fig. 4).

In male MDD patients, multivariate regression analysis showed that HAMD (t = -2.064, p < 0.05) was associated with education-related GMV. In female MDD patients, multivariate regression analysis showed that first episode (t = 2.626, p < 0.01), HAMD (t = 2.116, p < 0.05) and age (t = -4.244, p < 0.001) were associated with education-related GMV.

Discussion

There were three main findings in this study. (1) There were gender differences in clinical and demographic data. Specifically, the disease duration was longer in male MDD patients with SI group than in female patients with SI. The rates of medication use were lower in male MDD patients without SI than in female MDD patients without SI. The HAMD total score was significantly higher in the SI subgroup than the non-SI subgroup only in male MDD patients. (2) There was a gender difference in GMV of the ACC. Specifically, in MDD patients with SI, the GMV of right-sided ACC was greater in men than in women. In addition, only in female MDD patients, bilateral ACC GMV was significantly greater in the SI subgroup than in the non-SI subgroup. (3) There were gender differences in the relationship between ACC GMV and SI. Specifically, in male MDD patients, SI was positively associated with HAMD. In female MDD patients, SI was positively correlated with both HAMD and the GMV of the whole ACC.

Gender differences in clinical and demographic data

Our study found that male MDD patients with SI had a significantly longer disease duration than female MDD patients with SI, while male MDD patients without SI had a lower rate of medication use than female MDD patients without SI. This demonstrates that male MDD patients need a longer disease duration and less medications to develop SI, suggesting that males have a lower risk of suicide than females, which is consistent with previous research results [3, 32, 66].

According to the DSM criteria, disease duration is usually defined as the time since the onset of the mental illness [67, 68]. Some evidence suggests that long disease duration is associated with a poor prognosis for MDD patients [68]. This phenomenon can be attributed to the impact of disease duration on different biological systems [69]. For example, studies have found that disease duration is associated with abnormalities in the immune system and central nervous system [68, 70]. The damage may be associated with glutamate-mediated neuronal cytotoxicity and activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [71]. These mechanisms all lead to increased glucocorticoid secretion [72]. This biological abnormality may be the result of a model of neurodegenerative disease [73, 74]. In this model, the biological abnormality begins at the start of the illness and worsens over the course of the illness [73,74,75]. Studies have shown that atypical antipsychotics and antidepressants with manic and mood-stabilizing effects can block neurodegenerative processes associated with chronic illness, especially during the first year of illness [75,76,77]. Long disease duration and poor medication adherence may increase the risk of SI in patients with MDD [68]. Antidepressants primarily alleviate depressive symptoms by modulating central monoamine neurotransmitter function, enhancing synaptic plasticity, and ameliorating negative cognitive biases [78, 79]. These antidepressants may indirectly reduce SI risk, but their effects vary by drugs, individuals, and genders, and evidence remains inconsistent [79, 80]. For decades, researchers have persistently investigated whether gender differences exist in antidepressant treatment efficacy, yet evidence remains inconclusive [81]. Even if differences exist, it is unclear whether they are influenced by factors such as antidepressant class, menopausal status, body mass index, hormonal interactions, or pharmacokinetics [81]. In the present study, male patients with MDD demonstrated greater resistance to the risk of SI. Previous studies have shown that suicide attempts are more common in females, whereas successful suicides are more common in males [82]. Women tend to internalize problems, leading to low self-esteem and worsening depression, whereas men may express depression through aggressive behavior, poor impulse control, substance abuse, irritability, agitation and suicide [83]. Gender differences in disease duration and medication adherence may be the result of a combination of biological constructs and social roles [84,85,86].

In addition, the present study found that there was a difference in HAMD between the SI and non-SI subgroups only in male patients with MDD. In patients with MDD, higher SI is often associated with more severe depressive symptoms [87]. However, in female individuals, estrogen plays a role in the neural circuits that contribute to depression, including the serotonin system, the noradrenaline system and the dopamine system [88, 89]. The neuroprotective effects of estrogen have been shown to be useful in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases [90, 91]. During menopause, the neuroprotective effects of estrogen diminish as estrogen levels in the central nervous system fluctuate and decline, which may have a negative psychological impact on some women [91]. In addition, menopausal symptoms can seriously affect a woman’s quality of life [92]. Therefore, the effect of estrogen on depressive symptoms in women may result in the SI and non-SI groups of women with MDD not showing differences in HAMD.

Gender differences in GMV of the ACC

In the present study, we found that among MDD patients with SI, the GMV of the right-sided ACC was greater in males than in females, suggesting that there is a gender difference in the GMV of the ACC in MDD patients with SI. This phenomenon is consistent with previous studies [93,94,95,96]. A large body of data suggests that there are gender differences in brain structure and brain function in patients with MDD [93,94,95,96]. Volume changes observed throughout the brain in men and women with MDD differ in magnitude, laterality, and direction [94,95,96]. Differences in 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) synthesis and 5-HT autoreceptor 1 A (5-HT1A) density are also found in MDD patients of different sexes [97,98,99]. In addition, there are gender differences in the activation of several components of the HPA axis in MDD patients during stressful situations [100]. Women with MDD typically have higher cortisol levels and greater sensitivity to corticotropin-releasing factor than men with MDD [101,102,103]. Both male and female MDD patients originate from alterations in most of the different genes that converge in partially similar functional pathways, revealing significant sexual dimorphism in MDD patients at the transcriptional level [93]

In patients with MDD with SI, the GMV of the ACC exhibited gender differences, with males showing less atrophy, possibly indicating less damage. Women are almost twice as likely as men to develop MDD, and this gender difference is one of the strongest findings in psychopathology research [30, 84]. Antidepressants are the first-line treatment for MDD patients, but more than 30 per cent of patients have an inadequate response to initial medication [104,105,106,107]. For patients with MDD who do not respond to antidepressants after two adequate trials, augmentation strategies with antipsychotics or mood stabilizing medications should be used [104, 108, 109]. MDD patients of different genders seem to have different pharmacological profiles, and augmentation strategies lead to a more prominent clinical response in female patients [107, 110, 111]. In other words, female MDD patients on medication experience a higher degree of remission of clinical symptoms, including SI, than male MDD patients [107]. Thus, among MDD patients with SI who have similar medication profiles, women may have greater brain damage than men.

Similarly, we found that GMV of bilateral ACC in the SI subgroup was significantly greater than that in the non-SI group among female MDD patients only, suggesting that female MDD patients with SI have less bilateral ACC atrophy, which is in line with previous findings [112, 113]. The ACC plays an important role in the cognitive reappraisal of negative emotions, in particular the attentional control network [114, 115]. MDD patients with SI typically have better cognitive control, as evidenced by non-impulsivity and greater ACC GMV [112]. This non-impulsivity is also seen in patients with intense SI and in highly lethal suicide attempters, as evidenced by changes in brain globus pallidum volume [116, 117]. Chronic high stress-induced suicidal behavior is associated with increased GMV [112]. Increased microglia density in suicidal individuals may be a result of pre-suicide stress [118]. This microglia activation leads to an increase in somatic cell size and coarsening of the branching process, which manifests as larger GMV [112, 119].

However, in the present study, we did not find greater ACC GMV in the SI group among male MDD patients. This may be due to the fact that the present study did not exclude patients who smoked, which increases the risk of MDD onset, the severity of clinical symptoms and relapse [120]. Previous studies have found that smoking may increase the risk of suicidal behavior by increasing aggression, impulsivity and reducing sleep quality [121]. Smoking is also strongly associated with SI and suicide attempts [122, 123]. In China, female smokers are quite rare, with the proportion of male smokers being as high as 55%, compared to only 4% of female smokers [124, 125]. We hypothesize that the proportion of smokers among male MDD patients may be greater. Therefore, the effect of smoking on SI may be responsible for the lack of difference in ACC GMV between male MDD patients with and without SI.

Gender differences in the relationship between GMV of the ACC and SI

The present study found that SI was positively associated with HAMD in both male and female MDD patients, which is consistent with previous studies [41, 87, 126]. SI, as the initial stage of suicidal behaviors is influenced by a combination of genetic and environmental risk factors [127, 128]. Most psychiatric disorders, including depression, increase suicide risk [87, 127, 129,130,131]. Particularly in patients with MDD, higher SI is often associated with more severe depressive symptoms [87]. Treatments to alleviate depressive symptoms in patients with MDD also concomitantly reduce SI [79, 132,133,134,135]. One of the physiological mechanisms may be related to serum cystatin C (Cys C) [136,137,138]. Cys C plays a role in several aspects of bioactivity and neurophysiology and affects the risk of depression in several ways [136,137,138]. Changes in Cys C levels may also lead to increased neuronal inflammation, which can increase SI in patients with MDD [139,140,141]. Cys C may also increase SI in depressed patients by inducing neuronal apoptosis [139, 142, 143]. MDD patients is often associated with traumatic experiences [87]. Traumatic experiences often lead to a wider range of SI [87]. Depressive symptoms in patients with MDD are closely and independently associated with SI [144]. Individuals with SI typically have higher levels of dysphoria, but depressive symptoms do not explain the relationship between high levels of dysphoria and SI [144]. Therefore, further research is needed to investigate the relationship between SI and depressive symptoms.

In the present study, SI in female MDD patients was positively associated with GMV of the whole ACC. This finding was also confirmed in subsequent regression equation. The ACC is a structure in the medial prefrontal cortex [145]. It is an important region for integrating cognition, emotional input, social cognition and emotion regulation, and is central to neuroanatomical models of depression [145,146,147,148]. Abnormalities in the ACC have been linked to suicide in multiple psychiatric diagnostic categories, including MDD [113, 148,149,150]. Recent studies have shown that multiple psychiatric disorders are congruent across certain brain networks [146, 147, 151]. In this study, GMV of the ACC in female MDD patients increased with increasing SI. This may be due to increased brain plasticity resulting from hyperactivity in the ACC, which increases volume [152, 153]. This may be a compensatory mechanism for emotion regulation to alleviate abnormalities of ‘top-down’ regulation in the frontal lobe [113]. In addition, epigenetic dysregulation of glucocorticoid receptor and serotonin receptor binding also plays an important role in this process [154,155,156]. Taken together, ACC may be involved in the pathomechanism of SI in female MDD patients, suggesting that GMV of the ACC may be a biomarker of SI in MDD patients.

However, this result was not found in male MDD patients in the present study. This may be due to the fact that smokers were not excluded from this study and there was a higher proportion of smokers among male MDD patients [124, 125]. Smoking may increase the risk of suicidal behavior [121,122,123]. The direct toxic effects of smoking may damage the cerebrovascular system while reducing oxidative imbalance [157, 158]. Lifestyle factors, including smoking, have been associated with various structural brain markers [159,160,161]. In particular, non-smoking is associated with greater GMV [162, 163]. Therefore, the relationship between ACC GMV and SI in male MDD patients may be affected by smoking, resulting in a no statistical association between the two.

In addition, our study found an association between education and GMV of right-sided ACC only in female MDD patients, which is consistent with previous studies [164, 165]. ACC has been associated with learning and higher control over reward-related areas [165, 166]. Individuals with long-term education are more likely to accept tasks with delayed but higher financial rewards [165, 166]. This performance may be related to structural representations of ACC [165, 166]. The relationship between education level and GMV of the ACC is also mediated by body mass index (BMI) [167, 168]. Some studies have reported a strong positive correlation between BMI and MDD [169, 170]. Depression is more severe in obese MDD patients compared to non-obese MDD patients [171]. In addition, among MDD patients taking antidepressants, overweight patients have a worse prognosis than those of normal weight [170, 171]. There may be gender differences in the association between BMI and MDD, with this association being stronger in female patients [169, 170]. This may be why, among female MDD patients, an association between education and right-sided ACC GMV was found only in the SI subgroup.

Limitations

This study still has some limitations. First, there were significant differences in HAMD scores between MDD patients with and without SI. Although general linear models can compensate for differences in covariates to some extent, the relationship between depressive symptoms and SI and structural brain abnormalities requires further investigation. Second, the SI was collected via HAMD item 3 rather than via a structured SI-specific instrument. This study requires a structured scale to measure SI. Third, the GMV of the ACC and SI is affected by smoking, obesity, sex hormones, and other factors. These influences cannot be quantified due to the lack of data in this part of the study. Fourth, the database lacks documentation specifying whether diagnoses were based on the DSM-IV or ICD-10. Future studies should employ consistent diagnostic criteria or clearly document indicate the diagnostic system used. Finally, due to the limitations of a cross-sectional design, this study was unable to explain the direct causal relationship between SI and ACC GMV across gender.

Conclusions

In summary, this study found gender differences in the clinical data. Male MDD patients with SI had a longer disease duration than female MDD patients, and males in the non-SI subgroup had a lower rate of medication use than females. Only male MDD patients with SI had significantly higher HAMD total score than male MDD patients without SI. There was a gender difference in the GMV of the ACC. The GMV of the right-sided ACC was greater in the male SI subgroup than in female SI subgroup. Only in female MDD patients, the GMV of bilateral ACC was significantly greater in the SI subgroup than in the non-SI subgroup. Furthermore, there was a sex difference in the relationship between GMV of the ACC and SI. SI was positively associated with HAMD score in both men and women with MDD, whereas SI was positively associated with GMV of the ACC in female MDD patients only. However, there were methodological limitations to this study, including differences in HAMD scores between MDD patients with and without SI that may have influenced the findings, the lack of a structured scale to measure SI, the failure to quantify influences such as smoking, obesity, and sex hormones, and the inability of cross-sectional studies to determine causality between SI and ACC GMV. Future studies can use structured instruments to measure SI, control for variables such as smoking, obesity, and sex hormones, and explore the causal relationship between SI and ACC GMV through longitudinal studies.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [ZXY], upon reasonable request.

References

Zhdanava M, Pilon D, Ghelerter I, Chow W, Joshi K, Lefebvre P, et al. The prevalence and national burden of treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82:20m13699.

Dong R, Haque A, Wu HE, Placide J, Yu L, Zhang X. Sex differences in the association between suicide attempts and glucose disturbances in first-episode and drug naive patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2021;292:559–64.

Guo J, Wang L, Zhao X, Wang D, Zhang X. Sex difference in association between suicide attempts and lipid profile in first-episode and drug naive patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;172:24–33.

Shorey S, Ng ED, Wong CHJ. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61:287–305.

Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:211–24.

Dong M, Wang SB, Li Y, Xu DD, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, et al. Prevalence of suicidal behaviors in patients with major depressive disorder in China: A comprehensive meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:32–39.

Dumais A, Lesage AD, Alda M, Rouleau G, Dumont M, Chawky N, et al. Risk factors for suicide completion in major depression: a case-control study of impulsive and aggressive behaviors in men. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2116–24.

Trivedi MH, Morris DW, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Gaynes BN, Kurian BT, et al. Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics associated with suicidal ideation in depressed outpatients. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:113–22.

Sokero TP, Melartin TK, Rytsala HJ, Leskela US, Lestela-Mielonen PS, Isometsa ET. Suicidal ideation and attempts among psychiatric patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1094–100.

Lee K, Kim S, Jo JK. The relationships between abnormal serum lipid levels, depression, and suicidal ideation according to sex. J Clin Med. 2022;11:2119.

Sindermann L, Redlich R, Opel N, Bohnlein J, Dannlowski U, Leehr EJ. Systematic transdiagnostic review of magnetic-resonance imaging results: depression, anxiety disorders and their co-occurrence. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;142:226–39.

Chen L, Wang Y, Niu C, Zhong S, Hu H, Chen P, et al. Common and distinct abnormal frontal-limbic system structural and functional patterns in patients with major depression and bipolar disorder. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;20:42–50.

Lemke H, Romankiewicz L, Forster K, Meinert S, Waltemate L, Fingas SM, et al. Association of disease course and brain structural alterations in major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2022;39:441–51.

Ibrahim HM, Kulikova A, Ly H, Rush AJ, Sherwood Brown E. Anterior cingulate cortex in individuals with depressive symptoms: a structural MRI study. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2022;319:111420.

Chai Y, Gehrman P, Yu M, Mao T, Deng Y, Rao J, et al. Enhanced amygdala-cingulate connectivity associates with better mood in both healthy and depressive individuals after sleep deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2023;120:e2214505120.

Belleau EL, Treadway MT, Pizzagalli DA. The impact of stress and major depressive disorder on hippocampal and medial prefrontal cortex morphology. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85:443–53.

Riva-Posse P, Holtzheimer PE, Mayberg HS. Cingulate-mediated depressive symptoms in neurologic disease and therapeutics. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019;166:371–79.

Mertse N, Denier N, Walther S, Breit S, Grosskurth E, Federspiel A, et al. Associations between anterior cingulate thickness, cingulum bundle microstructure, melancholia and depression severity in unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2022;301:437–44.

Smith ML, Asada N, Malenka RC. Anterior cingulate inputs to nucleus accumbens control the social transfer of pain and analgesia. Science. 2021;371:153–59.

Li XH, Matsuura T, Xue M, Chen QY, Liu RH, Lu JS, et al. Oxytocin in the anterior cingulate cortex attenuates neuropathic pain and emotional anxiety by inhibiting presynaptic long-term potentiation. Cell Rep. 2021;36:109411.

Hu SW, Zhang Q, Xia SH, Zhao WN, Li QZ, Yang JX, et al. Contralateral projection of anterior cingulate cortex contributes to mirror-image pain. J Neurosci. 2021;41:9988–10003.

Bliss-Moreau E, Santistevan AC, Bennett J, Moadab G, Amaral DG. Anterior cingulate cortex ablation disrupts affective vigor and vigilance. J Neurosci. 2021;41:8075–87.

Lewis CP, Port JD, Blacker CJ, Sonmez AI, Seewoo BJ, Leffler JM, et al. Altered anterior cingulate glutamatergic metabolism in depressed adolescents with current suicidal ideation. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:119.

Bani-Fatemi A, Tasmim S, Graff-Guerrero A, Gerretsen P, Strauss J, Kolla N, et al. structural and functional alterations of the suicidal brain: an updated review of neuroimaging studies. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2018;278:77–91.

Pizzagalli DA. Frontocingulate dysfunction in depression: toward biomarkers of treatment response. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:183–206.

Krumm S, Checchia C, Koesters M, Kilian R, Becker T. Men’s views on depression: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative research. Psychopathology. 2017;50:107–24.

Oliffe JL, Ogrodniczuk JS, Gordon SJ, Creighton G, Kelly MT, Black N, et al. Stigma in male depression and suicide: a canadian sex comparison study. Community Ment Health J. 2016;52:302–10.

Kuehner C. Why is depression more common among women than among men?. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:146–58.

Rainville JR, Hodes GE. Inflaming sex differences in mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:184–99.

Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull. 2017;143:783–822.

Breslau J, Gilman SE, Stein BD, Ruder T, Gmelin T, Miller E. Sex differences in recent first-onset depression in an epidemiological sample of adolescents. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1139.

Azorin JM, Belzeaux R, Fakra E, Kaladjian A, Hantouche E, Lancrenon S, et al. Gender differences in a cohort of major depressive patients: further evidence for the male depression syndrome hypothesis. J Affect Disord. 2014;167:85–92.

Sa J, Choe CS, Cho CB, Chaput JP, Lee J, Hwang S. Sex and racial/ethnic differences in suicidal consideration and suicide attempts among US college students, 2011-2015. Am J Health Behav. 2020;44:214–31.

Carretta RF, McKee SA, Rhee TG. Gender differences in risks of suicide and suicidal behaviors in the USA: a narrative review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2023;25:809–24.

Wang S, Xu H, Li S, Jiang Z, Wan Y. Sex differences in the determinants of suicide attempt among adolescents in China. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;49:101961.

Hu FH, Zhao DY, Fu XL, Zhang WQ, Tang W, Hu SQ, et al. Gender differences in suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide death among people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. HIV Med. 2023;24:521–32.

Liu D, Lei G, Li D, Deng H, Zhang XY, Dang Y. Depression, rumination, and suicide attempts in adolescents with mood disorders: sex differences in this relationship. J Clin Psychiatry. 2024;85:23m15136.

Arnone D. Functional MRI findings, pharmacological treatment in major depression and clinical response. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;91:28–37.

Dunlop BW, Mayberg HS. Neuroimaging-based biomarkers for treatment selection in major depressive disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2014;16:479–90.

Chen Z, Xu T, Li Q, Shu Y, Zhou X, Guo T, et al. Grey matter abnormalities in major depressive disorder patients with suicide attempts: A systematic review of age-specific differences. Heliyon. 2024;10:e24894.

Guo Y, Jiang X, Jia L, Zhu Y, Han X, Wu Y, et al. Altered gray matter volumes and plasma IL-6 level in major depressive disorder patients with suicidal ideation. Neuroimage Clin. 2023;38:103403.

Wang L, Zhao Y, Edmiston EK, Womer FY, Zhang R, Zhao P, et al. Structural and functional abnormities of amygdala and prefrontal cortex in major depressive disorder with suicide attempts. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:923.

Liu J, Zhang H, Wu Y, Li W, Li M, Yuan X, et al. Sex differences in cortical structural alterations in major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation. Depress Anxiety. 2025;2025:1706750.

Yang X, Peng Z, Ma X, Meng Y, Li M, Zhang J, et al. Sex differences in the clinical characteristics and brain gray matter volume alterations in unmedicated patients with major depressive disorder. Sci Rep. 2017;7:2515.

Yan CG, Chen X, Li L, Castellanos FX, Bai TJ, Bo QJ, et al. Reduced default mode network functional connectivity in patients with recurrent major depressive disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:9078–83.

Button KS, Ioannidis JP, Mokrysz C, Nosek BA, Flint J, Robinson ES, et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:365–76.

Poldrack RA, Baker CI, Durnez J, Gorgolewski KJ, Matthews PM, Munafo MR, et al. Scanning the horizon: towards transparent and reproducible neuroimaging research. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18:115–26.

Botvinik-Nezer R, Holzmeister F, Camerer CF, Dreber A, Huber J, Johannesson M, et al. Variability in the analysis of a single neuroimaging dataset by many teams. Nature. 2020;582:84–88.

Ciric R, Rosen AFG, Erus G, Cieslak M, Adebimpe A, Cook PA, et al. Mitigating head motion artifact in functional connectivity MRI. Nat Protoc. 2018;13:2801–26.

Chen X, Lu B, Li HX, Li XY, Wang YW, Castellanos FX, et al. The DIRECT consortium and the REST-meta-MDD project: towards neuroimaging biomarkers of major depressive disorder. Psychoradiology. 2022;2:32–42.

Yan CG, Wang XD, Zuo XN, Zang YF. DPABI: data processing & analysis for (Resting-State) brain imaging. Neuroinformatics. 2016;14:339–51.

Yan CG, Cheung B, Kelly C, Colcombe S, Craddock RC, Di Martino A, et al. A comprehensive assessment of regional variation in the impact of head micromovements on functional connectomics. Neuroimage. 2013;76:183–201.

Long Y, Cao H, Yan C, Chen X, Li L, Castellanos FX, et al. Altered resting-state dynamic functional brain networks in major depressive disorder: findings from the REST-meta-MDD consortium. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26:102163.

Liu PH, Li Y, Zhang AX, Sun N, Li GZ, Chen X, et al. Brain structural alterations in mdd patients with gastrointestinal symptoms: evidence from the REST-meta-MDD project. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;111:110386.

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62.

Sun XY, Li YX, Yu CQ, Li LM. [Reliability and validity of depression scales of chinese version: a systematic review]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2017;38:110–16.

Lin GX. [Uses of HAMA the rating scale in neurosis]. Zhonghua Shen Jing Jing Shen Ke Za Zhi. 1986;19:342–4.

Vuorilehto M, Valtonen HM, Melartin T, Sokero P, Suominen K, Isometsa ET. Method of assessment determines prevalence of suicidal ideation among patients with depression. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29:338–44.

Ge F, Jiang J, Wang Y, Yuan C, Zhang W. Identifying suicidal ideation among chinese patients with major depressive disorder: evidence from a real-world hospital-based study in China. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:665–72.

Li X, Liu H, Hou R, Baldwin DS, Li R, Cui K, et al. Prevalence, clinical correlates and IQ of suicidal ideation in drug naive chinese han patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2019;248:59–64.

Chao-Gan Y, Yu-Feng Z. DPARSF: A MATLAB toolbox for “pipeline” data analysis of resting-state fMRI. Front Syst Neurosci. 2010;4:13.

Ashburner J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage. 2007;38:95–113.

Carlson JM, Fang L, Koster EHW, Andrzejewski JA, Gilbertson H, Elwell KA, et al. Neuroplastic changes in anterior cingulate cortex gray matter volume and functional connectivity following attention bias modification in high trait anxious individuals. Biol Psychol. 2022;172:108353.

Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31:968–80.

Frazier JA, Chiu S, Breeze JL, Makris N, Lange N, Kennedy DN, et al. Structural brain magnetic resonance imaging of limbic and thalamic volumes in pediatric bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1256–65.

Pompili M, Innamorati M, Mosticoni S, Lester D, Del Casale A, Ardenghi G, et al. Suicide attempts in major affective disorders. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2007;4:106–10.

Breitborde NJ, Srihari VH, Woods SW. Review of the operational definition for first-episode psychosis. Early Inter Psychiatry. 2009;3:259–65.

Altamura AC, Serati M, Buoli M. Is duration of illness really influencing outcome in major psychoses?. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69:403–17.

Altamura AC, Buoli M, Serati M. Duration of illness and duration of untreated illness in relation to drug response in psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychiatry. 2011;1:81–90.

Arango C, Breier A, McMahon R, Carpenter WT Jr., Buchanan RW. The relationship of clozapine and haloperidol treatment response to prefrontal, hippocampal, and caudate brain volumes. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1421–7.

Matsuo T, Izumi Y, Kume T, Takada-Takatori Y, Sawada H, Akaike A. Protective effect of aripiprazole against glutamate cytotoxicity in dopaminergic neurons of rat mesencephalic cultures. Neurosci Lett. 2010;481:78–81.

Altamura AC, Bobo WV, Meltzer HY. Factors affecting outcome in schizophrenia and their relevance for psychopharmacological treatment. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22:249–67.

Altamura AC, Buoli M, Pozzoli S. Role of immunological factors in the pathophysiology and diagnosis of bipolar disorder: comparison with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;68:21–36.

Skeppar P, Thoor R, Agren S, Isakson A-C, Skeppar I, Persson BA, et al. Neurodevelopmental disorders with comorbid affective disorders sometimes produce psychiatric conditions traditionally diagnosed as schizophrenia. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2013;10:123–34.

Andreasen NC. The lifetime trajectory of schizophrenia and the concept of neurodevelopment. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2010;12:409–15.

van Haren NE, Schnack HG, Cahn W, van den Heuvel MP, Lepage C, Collins L, et al. Changes in cortical thickness during the course of illness in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:871–80.

Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Ziebell S, Pierson R, Magnotta V. Long-term antipsychotic treatment and brain volumes: a longitudinal study of first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:128–37.

Harmer CJ, Duman RS, Cowen PJ. How do antidepressants work? new perspectives for refining future treatment approaches. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:409–18.

Hetrick SE, McKenzie JE, Bailey AP, Sharma V, Moller CI, Badcock PB, et al. New generation antidepressants for depression in children and adolescents: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;5:Cd013674.

Björkholm C, Monteggia LM. BDNF - a key transducer of antidepressant effects. Neuropharmacology. 2016;102:72–9.

Sramek JJ, Cutler NR. The impact of gender on antidepressants. Biological basis sex differences Psychopharmacol. 2011;8:231–49.

Miranda-Mendizabal A, Castellvi P, Pares-Badell O, Alayo I, Almenara J, Alonso I, et al. Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int J Public Health. 2019;64:265–83.

Angst J, Gamma A, Gastpar M, Lepine JP, Mendlewicz J, Tylee A, et al. Gender differences in depression. Epidemiological findings from the European DEPRES I and II studies. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;252:201–9.

Parker G, Brotchie H. Gender differences in depression. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22:429–36.

Swetlitz N. Depression’s Problem With Men. AMA J Ethics. 2021;23:E586–89.

Tian X, Liu XE, Bai F, Li M, Qiu Y, Jiao Q, et al. Sex differences in correlates of suicide attempts in Chinese Han first-episode and drug-naive major depressive disorder with comorbid subclinical hypothyroidism: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. 2024;14:e3578.

Cai H, Jin Y, Liu S, Zhang Q, Zhang L, Cheung T, et al. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and planning in patients with major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of observation studies. J Affect Disord. 2021;293:148–58.

Jacobs EG, Holsen LM, Lancaster K, Makris N, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Remington A, et al. 17beta-estradiol differentially regulates stress circuitry activity in healthy and depressed women. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:566–76.

Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Liu L, Gracia CR, Nelson DB, Hollander L. Hormones and menopausal status as predictors of depression in women in transition to menopause. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:62–70.

Bustamante-Barrientos FA, Mendez-Ruette M, Ortloff A, Luz-Crawford P, Rivera FJ, Figueroa CD, et al. The impact of estrogen and estrogen-like molecules in neurogenesis and neurodegeneration: beneficial or harmful?. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:636176.

Herson M, Kulkarni J. Hormonal agents for the treatment of depression associated with the menopause. Drugs Aging. 2022;39:607–18.

Avis NE, Ory M, Matthews KA, Schocken M, Bromberger J, Colvin A. Health-related quality of life in a multiethnic sample of middle-aged women: study of women’s health across the nation (SWAN). Med Care. 2003;41:1262–76.

Labonte B, Engmann O, Purushothaman I, Menard C, Wang J, Tan C, et al. Sex-specific transcriptional signatures in human depression. Nat Med. 2017;23:1102–11.

Kong L, Chen K, Womer F, Jiang W, Luo X, Driesen N, et al. Sex differences of gray matter morphology in cortico-limbic-striatal neural system in major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:733–9.

Videbech P, Ravnkilde B. Hippocampal volume and depression: a meta-analysis of MRI studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1957–66.

Hastings RS, Parsey RV, Oquendo MA, Arango V, Mann JJ. Volumetric analysis of the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:952–9.

Frey BN, Skelin I, Sakai Y, Nishikawa M, Diksic M. Gender differences in alpha-[(11)C]MTrp brain trapping, an index of serotonin synthesis, in medication-free individuals with major depressive disorder: a positron emission tomography study. Psychiatry Res. 2010;183:157–66.

Kaufman J, Sullivan GM, Yang J, Ogden RT, Miller JM, Oquendo MA, et al. Quantification of the serotonin 1A receptor using PET: identification of a potential biomarker of major depression in males. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:1692–9.

Underwood MD, Kassir SA, Bakalian MJ, Galfalvy H, Mann JJ, Arango V. Neuron density and serotonin receptor binding in prefrontal cortex in suicide. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:435–47.

Bangasser DA, Valentino RJ. Sex differences in stress-related psychiatric disorders: neurobiological perspectives. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35:303–19.

Chopra KK, Ravindran A, Kennedy SH, Mackenzie B, Matthews S, Anisman H, et al. Sex differences in hormonal responses to a social stressor in chronic major depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1235–41.

Young EA, Altemus M. Puberty, ovarian steroids, and stress. Ann N. Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:124–33.

Kunugi H, Ida I, Owashi T, Kimura M, Inoue Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Assessment of the dexamethasone/CRH test as a state-dependent marker for hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis abnormalities in major depressive episode: a multicenter study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:212–20.

Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, Tourjman SV, Bhat V, Blier P, et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 3. pharmacological treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61:540–60.

Cleare A, Pariante CM, Young AH, Anderson IM, Christmas D, Cowen PJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2008 british association for psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:459–525.

Bauer M, Severus E, Kohler S, Whybrow PC, Angst J, Moller HJ, et al. World federation of societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders. part 2: maintenance treatment of major depressive disorder-update 2015. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2015;16:76–95.

Moderie C, Nunez N, Fielding A, Comai S, Gobbi G. Sex differences in responses to antidepressant augmentations in treatment-resistant depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;25:479–88.

Gobbi G, Ghabrash MF, Nunez N, Tabaka J, Di Sante J, Saint-Laurent M, et al. Antidepressant combination versus antidepressants plus second-generation antipsychotic augmentation in treatment-resistant unipolar depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;33:34–43.

Ghabrash MF, Comai S, Tabaka J, Saint-Laurent M, Booij L, Gobbi G. Valproate augmentation in a subgroup of patients with treatment-resistant unipolar depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17:165–70.

Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ. Sex differences and the neurobiology of affective disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:111–28.

Bartova L, Dold M, Fugger G, Kautzky A, Mitschek MMM, Weidenauer A, et al. Sex-related effects in major depressive disorder: results of the european group for the study of resistant depression. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38:896–906.

Rizk MM, Rubin-Falcone H, Lin X, Keilp JG, Miller JM, Milak MS, et al. Gray matter volumetric study of major depression and suicidal behavior. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2019;283:16–23.

Duarte DGG, Neves MCL, Albuquerque MR, Turecki G, Ding Y, de Souza-Duran FL, et al. Structural brain abnormalities in patients with type I bipolar disorder and suicidal behavior. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2017;265:9–17.

Buhle JT, Silvers JA, Wager TD, Lopez R, Onyemekwu C, Kober H, et al. Cognitive reappraisal of emotion: a meta-analysis of human neuroimaging studies. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24:2981–90.

Shenhav A, Cohen JD, Botvinick MM. Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the value of control. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1286–91.

Dombrovski AY, Siegle GJ, Szanto K, Clark L, Reynolds CF, Aizenstein H. The temptation of suicide: striatal gray matter, discounting of delayed rewards, and suicide attempts in late-life depression. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1203–15.

Vang FJ, Ryding E, Traskman-Bendz L, van Westen D, Lindstrom MB. Size of basal ganglia in suicide attempters, and its association with temperament and serotonin transporter density. Psychiatry Res. 2010;183:177–9.

Steiner J, Bielau H, Brisch R, Danos P, Ullrich O, Mawrin C, et al. Immunological aspects in the neurobiology of suicide: elevated microglial density in schizophrenia and depression is associated with suicide. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:151–7.

LaVoie MJ, Card JP, Hastings TG. Microglial activation precedes dopamine terminal pathology in methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:47–57.

Leventhal AM, Kahler CW, Ray LA, Zimmerman M. Refining the depression-nicotine dependence link: patterns of depressive symptoms in psychiatric outpatients with current, past, and no history of nicotine dependence. Addict Behav. 2009;34:297–303.

Chang HB, Munroe S, Gray K, Porta G, Douaihy A, Marsland A, et al. The role of substance use, smoking, and inflammation in risk for suicidal behavior. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:33–41.

Grucza RA, Plunk AD, Krauss MJ, Cavazos-Rehg PA, Deak J, Gebhardt K, et al. Probing the smoking–suicide association: do smoking policy interventions affect suicide risk?. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:1487–94.

Poorolajal J, Darvishi N. Smoking and suicide: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0156348.

Zhang XY, Zhang RL, Pan M, Chen DC, Xiu MH, Kosten TR. Sex difference in the prevalence of smoking in Chinese schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44:986–8.

Zheng Y, Ji Y, Dong H, Chang C. The prevalence of smoking, second-hand smoke exposure, and knowledge of the health hazards of smoking among internal migrants in 12 provinces in China: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:655.

Khandoker AH, Luthra V, Abouallaban Y, Saha S, Ahmed KIU, Mostafa R, et al. Suicidal ideation is associated with altered variability of fingertip photo-plethysmogram signal in depressed patients. Front Physiol. 2017;8:501.

Dada O, Qian J, Al-Chalabi N, Kolla NJ, Graff A, Zai C, et al. Epigenetic studies in suicidal ideation and behavior. Psychiatr Genet. 2021;31:205–15.

Ropaj E. Hope and suicidal ideation and behaviour. Curr Opin Psychol. 2023;49:101491.

Schneider RA, Chen SY, Lungu A, Grasso JR. Treating suicidal ideation in the context of depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:497.

Nassan M, Daghlas I, Winkelman JW, Dashti HS, International Suicide Genetics C, Saxena R. Genetic evidence for a potential causal relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal behavior: a Mendelian randomization study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47:1672–79.

Dai Q, Zhou Y, Liu R, Wei S, Zhou H, Tian Y, et al. Alcohol use history increases the likelihood of suicide behavior among male chronic patients with schizophrenia in a Chinese population. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2022;52:716–24.

Hochschild A, Keilp JG, Madden SP, Burke AK, Mann JJ, Grunebaum MF. Ketamine vs midazolam: Mood improvement reduces suicidal ideation in depression. J Affect Disord. 2022;300:10–16.

Pan F, Shen Z, Jiao J, Chen J, Li S, Lu J, et al. Neuronavigation-Guided rTMS for the treatment of depressive patients with suicidal ideation: a double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trial. Clin Pharm Ther. 2020;108:826–32.

Ionescu DF, Fu DJ, Qiu X, Lane R, Lim P, Kasper S, et al. Esketamine nasal spray for rapid reduction of depressive symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder who have active suicide ideation with intent: results of a phase 3, double-blind, randomized study (ASPIRE II). Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;24:22–31.

Li X, Yu R, Huang Q, Chen X, Ai M, Zhou Y, et al. Alteration of whole brain ALFF/fALFF and degree centrality in adolescents with depression and suicidal ideation after electroconvulsive therapy: a resting-state fMRI study. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021;15:762343.

Daria S, Proma MA, Shahriar M, Islam SMA, Bhuiyan MA, Islam MR. Serum interferon-gamma level is associated with drug-naive major depressive disorder. SAGE Open Med. 2020;8:2050312120974169.

Zi M, Xu Y. Involvement of cystatin C in immunity and apoptosis. Immunol Lett. 2018;196:80–90.

Islam MR, Ali S, Karmoker JR, Kadir MF, Ahmed MU, Nahar Z, et al. Evaluation of serum amino acids and non-enzymatic antioxidants in drug-naive first-episode major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:333.

Sun T, Chen Q, Li Y. Associations of serum cystatin C with depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:576.

Brundin L, Bryleva EY, Thirtamara Rajamani K. Role of Inflammation in Suicide: From Mechanisms to Treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:271–83.

Pandey GN, Rizavi HS, Ren X, Fareed J, Hoppensteadt DA, Roberts RC, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines in the prefrontal cortex of teenage suicide victims. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:57–63.

Mitaki S, Nagai A, Sheikh AM, Terashima M, Isomura M, Nabika T, et al. Contribution of cystatin C gene polymorphisms to cerebral white matter lesions. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32:489–96.

Jia Z, Huang X, Wu Q, Zhang T, Lui S, Zhang J, et al. High-field magnetic resonance imaging of suicidality in patients with major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1381–90.

Ducasse D, Loas G, Dassa D, Gramaglia C, Zeppegno P, Guillaume S, et al. Anhedonia is associated with suicidal ideation independently of depression: A meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35:382–92.

Palomero-Gallagher N, Hoffstaedter F, Mohlberg H, Eickhoff SB, Amunts K, Zilles K. Human pregenual anterior cingulate cortex: structural, functional, and connectional heterogeneity. Cereb Cortex. 2019;29:2552–74.

Wise T, Radua J, Via E, Cardoner N, Abe O, Adams TM, et al. Common and distinct patterns of grey-matter volume alteration in major depression and bipolar disorder: evidence from voxel-based meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:1455–63.

Gradone AM, Champion G, McGregor KM, Nocera JR, Barber SJ, Krishnamurthy LC, et al. Rostral anterior cingulate connectivity in older adults with subthreshold depressive symptoms: A preliminary study. Aging Brain. 2023;3:100059.

van Heeringen K, Bijttebier S, Desmyter S, Vervaet M, Baeken C. Is there a neuroanatomical basis of the vulnerability to suicidal behavior? A coordinate-based meta-analysis of structural and functional MRI studies. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:824.

Wagner G, Koch K, Schachtzabel C, Schultz CC, Sauer H, Schlosser RG. Structural brain alterations in patients with major depressive disorder and high risk for suicide: evidence for a distinct neurobiological entity?. Neuroimage. 2011;54:1607–14.

He M, Ping L, Chu Z, Zeng C, Shen Z, Xu X. Identifying changes of brain regional homogeneity and cingulo-opercular network connectivity in first-episode, drug-naive depressive patients with suicidal ideation. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:856366.

Goodkind M, Eickhoff SB, Oathes DJ, Jiang Y, Chang A, Jones-Hagata LB, et al. Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:305–15.

Fears SC, Schur R, Sjouwerman R, Service SK, Araya C, Araya X, et al. Brain structure-function associations in multi-generational families genetically enriched for bipolar disorder. Brain. 2015;138:2087–102.

Lisy ME, Jarvis KB, DelBello MP, Mills NP, Weber WA, Fleck D, et al. Progressive neurostructural changes in adolescent and adult patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13:396–405.

Bartlett EA, Zanderigo F, Shieh D, Miller J, Hurley P, Rubin-Falcone H, et al. Serotonin transporter binding in major depressive disorder: impact of serotonin system anatomy. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:3417–24.

Pantazatos SP, Melhem NM, Brent DA, Zanderigo F, Bartlett EA, Lesanpezeshki M, et al. Ventral prefrontal serotonin 1A receptor binding: a neural marker of vulnerability for mood disorder and suicidal behavior?. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:4136–43.

Rizavi HS, Khan OS, Zhang H, Bhaumik R, Grayson DR, Pandey GN. Methylation and expression of glucocorticoid receptor exon-1 variants and FKBP5 in teenage suicide-completers. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13:53.

Pan Y, Shen J, Cai X, Chen H, Zong G, Zhu W, et al. Adherence to a healthy lifestyle and brain structural imaging markers. Eur J Epidemiol. 2023;38:657–68.

Xiang S, Jia T, Xie C, Cheng W, Chaarani B, Banaschewski T, et al. Association between vmPFC gray matter volume and smoking initiation in adolescents. Nat Commun. 2023;14:4684.

Li Y, Schoufour J, Wang DD, Dhana K, Pan A, Liu X, et al. Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy free of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;368:l6669.

Heger IS, Deckers K, Schram MT, Stehouwer CDA, Dagnelie PC, van der Kallen CJH, et al. Associations of the lifestyle for brain health index with structural brain changes and cognition: results from the maastricht study. Neurology. 2021;97:e1300–e12.

Cox SR, Lyall DM, Ritchie SJ, Bastin ME, Harris MA, Buchanan CR, et al. Associations between vascular risk factors and brain MRI indices in UK Biobank. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2290–300.

Elbejjani M, Auer R, Jacobs DR Jr, Haight T, Davatzikos C, Goff DC Jr, et al. Cigarette smoking and gray matter brain volumes in middle age adults: the CARDIA Brain MRI sub-study. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9:78.

Kharabian Masouleh S, Beyer F, Lampe L, Loeffler M, Luck T, Riedel-Heller SG, et al. Gray matter structural networks are associated with cardiovascular risk factors in healthy older adults. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38:360–72.

Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Landeau B, La Joie R, Mevel K, Mezenge F, Perrotin A, et al. Relationships between years of education and gray matter volume, metabolism and functional connectivity in healthy elders. Neuroimage. 2013;83:450–7.

Lotze M, Domin M, Schmidt CO, Hosten N, Grabe HJ, Neumann N. Income is associated with hippocampal/amygdala and education with cingulate cortex grey matter volume. Sci Rep. 2020;10:18786.

Heilbronner SR, Hayden BY. Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex: a bottom-up view. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2016;39:149–70.

Opel N, Redlich R, Kaehler C, Grotegerd D, Dohm K, Heindel W, et al. Prefrontal gray matter volume mediates genetic risks for obesity. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:703–10.

Kennedy JT, Collins PF, Luciana M. Higher adolescent body mass index is associated with lower regional gray and white matter volumes and lower levels of positive emotionality. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:413.

Faith MS, Flint J, Fairburn CG, Goodwin GM, Allison DB. Gender differences in the relationship between personality dimensions and relative body weight. Obes Res. 2001;9:647–50.

Holsen LM, Huang G, Cherkerzian S, Aroner S, Loucks EB, Buka S, et al. Sex differences in hemoglobin A1c levels related to the comorbidity of obesity and depression. J Women’s Health (Larchmt). 2021;30:1303–12.

Murphy JM, Horton NJ, Burke JD Jr, Monson RR, Laird NM, Lesage A, et al. Obesity and weight gain in relation to depression: findings from the stirling county study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33:335–41.

Acknowledgements

Members of the REST-meta-MDD Consortium provided the data for this study. We would like to express our appreciation and gratitude to all of the participants in this study.

Funding

This study supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82401809) and Science and Technology Innovation Cultivation Program of Beijing Union University (JZK30202508). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LX and XYZ performed analysis, made interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. NW, DW, and HZ helped draft the work and revise it critically. All authors made significant contributions to the paper to assess the important intellectual content, read and approved the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study used publicly available data from the REST-meta-MDD project. According to the project’s specifications, all participating sites obtained ethical approval from their respective institutional review committees, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. No additional ethical approval was required for the secondary analysis of the anonymized data, and all methodologies were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, L., Wu, N., Wang, D. et al. Gender differences in gray matter volume of the anterior cingulate cortex and suicidal ideation in patients with major depressive disorder: evidence from the REST-meta-MDD project. Transl Psychiatry 16, 42 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03784-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03784-8