Abstract

We report 14 cases of immune effector cell (IEC)-associated enterocolitis following chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy in multiple myeloma, with a 1.2% incidence overall (0.2% for idecabtagene vicleucel and 2.2% for ciltacabtagene autoleucel). Patients developed acute-onset symptoms (typically non-bloody Grade 3+ diarrhea) with negative infectious workup beginning a median of 92.5 days (range: 22–210 days) after CAR-T therapy and a median of 85 days after cytokine release syndrome resolution. Gut biopsies uniformly demonstrated inflammation, including intra-epithelial lymphocytosis and villous blunting. In one case where CAR-specific immunofluorescence stains were available, CAR T-cell presence was confirmed within the lamina propria. Systemic corticosteroids were initiated in 10 patients (71%) a median of 25.5 days following symptom onset, with symptom improvement in 40%. Subsequent infliximab or vedolizumab led to improvement in 50% and 33% of corticosteroid-refractory patients, respectively. Five patients (36%) have died from bowel perforation or treatment-emergent sepsis. In conclusion, IEC-associated enterocolitis is a distinct but rare complication of CAR-T therapy typically beginning 1–3 months after infusion. Thorough diagnostic workup is essential, including evaluation for potential T-cell malignancies. The early use of infliximab or vedolizumab may potentially hasten symptom resolution and lower reliance on high-dose corticosteroids during the post-CAR-T period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Several immune effector cell (IEC) therapies targeting B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) have been approved by the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), including chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies such as idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel) and ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel) [1, 2]. Common IEC-associated adverse events include cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), while rarer toxicities include IEC-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-like syndrome (IEC-HS) and late-onset neurotoxicity [3,4,5]. In the past five years, 3 reports of colitis manifesting as watery diarrhea have been reported following CD19-directed CAR-T therapy [6,7,8]. In one case, CAR T-cells expressing α4β7 integrin were found to be enriched within the colon lamina propria following treatment with tisagenlecleucel [8]. A similar case of diarrhea has recently been reported following cilta-cel in MM; however, in this case, the CAR-positive infiltrate was neoplastic consistent with T-cell lymphoma [9].

Treatment-emergent gastrointestinal (GI) toxicities following CAR-T therapy in MM have not been well characterized. Diarrhea was noted in 0.4% of patients in the ide-cel arm of KarMMa-3 (n = 1) and 2.4% of patients in the cilta-cel arm of CARTITUDE-4 (n = 5) [1, 2]; however, the details of chronology, further workup, and treatment in these six cases are unclear. Diarrhea following CAR-T therapy can potentially be attributed to other causes such as bacterial infections, clinically significant cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation, or organ-specific manifestations of inflammation during active CRS. Whether IEC-associated enteritis or colitis can occur in the absence of a neoplastic etiology following BCMA-directed CAR-T therapy in MM, as noted in one case following CD19-directed CAR-T therapy in lymphoma [8], is unknown.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of cases of diarrhea, enterocolitis, or colitis following commercial ide-cel or cilta-cel at 11 centers within the United States Multiple Myeloma Immunotherapy Consortium. Cases were identified by each participating center through internal discussions at standing myeloma-related and/or CAR-T related meetings for commercial infusions that may have met the above criteria. For centers with dedicated IEC compliance programs or long-term follow-up programs, these program databases were also queried. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for participation within the Consortium at each participating center. Patients were treated according to the local standard of care at each center. Collected data points included baseline patient characteristics, CAR-T-related information, post-infusion toxicities, summaries of biopsy reports (if available), and patient outcomes. CRS and ICANS were graded using American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) consensus criteria, while other symptoms (diarrhea, colitis, and enterocolitis) were graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0.

Endoscopic biopsies were reviewed by board-certified anatomic pathologists or hematopathologists at each institution. At one institution where the necessary reagents were available, multiplex immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were used to analyze the presence of the following markers: CD3, CD8, CD138, and camelid VHH (variable heavy chain of a heavy-chain antibody) seen in ciltacabtagene autoleucel. Additional information about the methods for these assays are shown in Supplementary Table S1. For all patients, data were analyzed utilizing descriptive methods including medians, percentages, and student t-tests to compare clinical parameters in patients with resolved IEC-associated enterocolitis versus patients who died secondary to enterocolitis or associated complications. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.2.3 (La Jolla, California, USA).

Results

We identified 14 cases of IEC-associated enteritis and/or colitis diagnosed at one of 11 centers within the US Multiple Myeloma Immunotherapy Consortium, in one case following ide-cel and in 13 cases following cilta-cel. This corresponds to an IEC-associated enterocolitis incidence of 1.2% overall out of 1287 infusions (636 ide-cel and 651 cilta-cel) across all study centers, with product-specific incidences of 0.2% for ide-cel and 2.2% for cilta-cel. Importantly, this figure excluded 3 cases of potential or confirmed T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, including a previously characterized patient who was managed at multiple institutions [9]; features of these 3 patients are summarized separately in Supplementary Table S2.

As detailed in Table 1, patients were evenly split between men and women and ranged in age from 39 to 79 at CAR-T infusion. One patient (7%) had a reported medical history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the distant past with no symptoms at time of infusion. Most patients (86%, n = 12) had previously undergone autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) without any post-transplantation diarrhea or engraftment syndrome. IEC-associated enterocolitis manifested as acute-onset diarrhea (non-bloody in all but one case) beginning a median of 92.5 days (range: 22–210 days) after CAR-T therapy and a median of 85 days after CRS resolution (range: 2–205 days). Diarrhea was grade 3 or higher in all cases, and 71% of patients (n = 10) reported concurrent abdominal pain. Computed tomography imaging (n = 13) showed small bowel or large bowel inflammation in 43% of cases (n = 6), including two cases of diffuse colonic pneumatosis (Fig. 1A). With regard to antecedent CRS and ICANS, 4 patients had maximum Grade 2 CRS, 9 maximum Grade 1 CRS, and 1 no CRS; one patient had developed Grade 2 ICANS previously. Management strategies for antecedent CRS or ICANS included tocilizumab (n = 11), corticosteroids (n = 9), and anakinra (n = 1). Three patients had developed delayed cranial nerve palsies following cilta-cel, with neurotoxicity resolution before enterocolitis onset in two of these cases. By the time of diarrhea onset, serum ferritin and C-reactive protein levels at symptom onset were below their peak values in all patients.

Top panel: Representative colitis-related images from different patients. Panel A: diffuse bowel wall pneumatosis and pneumoperitoneum on computed tomography imaging consistent with toxic megacolon, which subsequently required subtotal colectomy. Panel B: ulcerations noted on endoscopic evaluation of the transverse colon. Panel C: 10× magnification of colonic mucosa showing focal crypt dropout and increased apoptotic activity; minimal expansion by scattered eosinophils and focal intraepithelial lymphocytes are also seen. Bottom panel: Representative enteritis-related images from one patient. Marked infiltration of the lamina propria by T lymphocytes at low power (2×, panel D) and high power (10×, panel E). Immunohistochemical stain for CD3 (20×, panel F) demonstrates that the majority of the lamina propria cells and intraepithelial lymphocytes are T cells.

The results of endoscopic evaluations were available for 13 patients (93%): 6 patients underwent both esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy, 6 patients had only a colonoscopy, and 1 patient had only an EGD. Biopsies uniformly demonstrated evidence of inflammation in at least one area (Supplementary Table S3). Colonic biopsies (representative images in Fig. 1B, C) typically showed endoscopic evidence of ulceration with histological evidence of crypt dropout and increased apoptotic activity. Duodenal biopsies (representative images in Fig. 1D–F) typically showed villous blunting and increased intraepithelial lymphocytes. In several cases (n = 6), marked intra-epithelial lymphocytosis was noted. Chronic changes such as crypt architecture distortion were only rarely seen. Biopsy findings were often noted by interpreting pathologists to resemble those seen in graft-versus-host disease (GVHD); however, all patients had received autologous CAR-T therapy and no patients had previously undergone allogeneic transplantation. At one institution with access to antibody-based testing for the camelid VHH region found in cilta-cel (Fig. 2), multiplex immunofluorescence and IHC staining revealed CAR-transduced T cells (some CD8-positive and some CD8-negative) infiltrating into the duodenal lamina propria.

Multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) images from a duodenal FFPE biopsy of a patient who developed IEC-associated enterocolitis after ciltacabtagene autoleucel therapy for multiple myeloma. Panel A shows a representative merged image demonstrating presence of CAR+ (Camelid VHH+, red) T cells (CD3+, green) infiltrating the affected tissue. CD8 staining (yellow) determines CD8+ and CD8− T cell subsets among the T cells. Single channel images of the field of view are shown on the right. Panel B shows (1) Camelid VHH detection by mIF (left), (2) co-expression of CD3 and VHH (center) demonstrating that infiltrating CAR+ (red) cells are CAR-transduced CD3+ T cells (green), and (3) differential expression of CD8 and VHH (right) indicating that some but not all CAR-T cells are CD8+ (yellow) cells. Panel C shows representative images of different areas of the biopsy identifying CD3+ T cells (green) by mIF infiltrating the tissue (top). Those same regions from the IHC-stained slide are shown (bottom), demonstrating similar pattern of infiltration of CAR+ cells (VHH+), indicating that great majority of the infiltrating T cells are CAR-T cells. CAR chimeric antigen receptor, FFPE formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded, IEC immune effector cell, IHC Immunohistochemistry, VHH variable heavy chain of a heavy-chain antibody.

With regard to infectious workup, alternative bacterial causes of diarrhea were not identified at symptom onset. Median IgG level at symptom onset was 326.5 milligrams per deciliter (range: 25–778), and 71% (n = 10) of patients had received intravenous immunoglobulin within 30 days beforehand. Peripheral blood CMV assessment by quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing was performed in 11 cases: results were negative in 7 cases, below the lower level of detection in 2 cases, and frankly positive in two cases (peak values 186 and 12,800 international units per milliliter, respectively). Both patients with CMV viremia received intravenous ganciclovir with CMV clearance in one case and ongoing low-level positivity in the other. Immunohistochemical stains of enteric biopsies for bacterial and viral infections (including CMV) from biopsies were negative in all cases, including in both patients with CMV viremia.

With regard to treatment, systemic corticosteroids were initiated in 71% of cases (n = 10). This included six patients who received oral prednisone with a median starting dose of 0.87 milligrams (mg) per kilogram (kg) per day (range: 0.19–2 mg/kg/day) for a median duration of 21 days (range: 1–145 days) as well as four patients who received intravenous methylprednisolone with a median starting dose of 1.40 mg/kg/day (range: 1–2 mg/kg/day) for a median duration of 49 days (range: 20–68 days). Corticosteroids were initiated a median of 26 days (range: 1–80 days) following symptom onset, and 40% of steroid-treated patients had symptomatic improvement thereafter. Six patients with corticosteroid-refractory symptoms (43% of all cases) were subsequently started on infliximab based on American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines for managing immune-related adverse events (irAEs) following checkpoint inhibitors [10]. Median time to infliximab initiation was 61 days (range: 34–100 days) after diarrhea onset, and half of infliximab-treated patients had symptomatic improvement after 1–3 doses of infliximab. Given that α4β7 integrin may be overexpressed on CAR T-cells within the colon [8], the α4β7 integrin antagonist vedolizumab was prescribed in three patients (21% of all patients). Vedolizumab was initiated a median of 59 days (range: 40–120) after diarrhea onset, with one of three patients having symptomatic improvement but subsequently developing Clostridioides difficile infection requiring fecal microbiota transplantation.

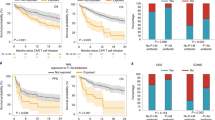

With a median follow-up of 187 days since diarrhea onset (range: 44–532 days), 4 patients have had diarrhea resolution (median time to resolution 113 days), including one patient who required a 145-day prednisone course with a taper and two patients who required 1–3 doses of infliximab concomitantly with corticosteroids. Five patients have ongoing diarrhea, including two patients with improved but ongoing symptoms. Five patients (36% of all cases) have died, either directly from bowel perforation secondary to IEC-associated enterocolitis (n = 3) or from treatment-emergent sepsis (n = 2). Characteristics of patients with symptom resolution (n = 4) versus deceased patients (n = 5) are shown in Supplementary Table S4. Albeit with small n, no significant differences were noted in terms of age, pertinent biomarkers, time to symptom onset, or time to corticosteroid initiation.

Discussion

This represents the largest case series of IEC-associated enterocolitis following any type of CAR-T therapy. Clinical and histological presentations were strikingly similar in most cases, suggesting that IEC-associated enterocolitis is a rare but distinct toxicity of CAR-T therapy characterized by non-bloody diarrhea with negative infectious workup beginning 1–3 months following CAR-T therapy. Inflammation is typically seen on enteric biopsies with a specific resemblance to the pattern seen in GVHD following allogeneic transplantation. The addition of biologic immunosuppressive agents (e.g., infliximab or vedolizumab dosed at weeks 0, 2, and 6) may benefit patients with corticosteroid-refractory symptoms. Indeed, in the setting of colitis as an irAE following immune checkpoint inhibition, ASCO guidelines recommend initiating infliximab as soon as 3 days after corticosteroids if symptoms do not begin to improve [10]. Vedolizumab may also be helpful given that α4β7 integrin (the target of vedolizumab) has been shown to be overexpressed on gut-trafficking CAR T cells [8]. Other management approaches such as ruxolitinib or lymphotoxic chemotherapy are considerations in refractory IEC-HS [4] and could be considered for life-threatening cases of enterocolitis as well. Of course, further research is needed to validate the utility of any of these immunosuppressive agents in this specific scenario. Based on our collective experience to date, key recommendations for diagnosing and managing IEC-associated enterocolitis are shown in Table 2.

IEC-associated enterocolitis remains a rare phenomenon, with an incidence of 1.2% out of over 1200 commercial or out-of-specification BCMA CAR-T infusions across all study centers. Comparing our observed product-specific incidences of 0.2% for ide-cel and 2.2% for cilta-cel is difficult given the novelty and rarity of this toxicity. The voluntary FDA Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) database, which has been used previously to characterize rare toxicities of CAR-T therapy [11], includes 22 reactions that may potentially be linked to IEC-associated enterocolitis (Supplemental Table S5). However, FAERS data do not have a denominator and it is unclear whether any of these reported reactions represent infectious sequelae, pre-existing conditions, or duplicate entries (either with each other or with cases described here). The recently characterized case of CAR-positive T-cell lymphoma following cilta-cel is not isolated [9], but such cases are even rarer in our experience. Failure of enterocolitis symptoms to improve with corticosteroids and biological immunosuppressive agents should prompt consideration of a lymphoproliferative process for which, after diagnostic confirmation of neoplastic T cells, drugs such as cyclosporine may be more appropriate [12].

The mechanism of IEC-associated enterocolitis remains unclear. BCMA is expressed on GI-associated lymphoid tissue and plays a role in promoting lymphocyte class switching toward IgA production [13, 14]. However, given that BCMA expression is similar in tonsillar and enteric tissue [13] and that similar presentations have occurred with CD19-directed CAR-T therapy [6,7,8], direct on-target toxicity does not seem to fully explain IEC-associated enterocolitis. BCMA in the lamina propria is mostly found on long-lived IgA plasma cells, which likely modulate gut immunity and the gut microbiome [15,16,17]. It is thus possible that eradication of these BCMA-positive plasma cells can lead to an autoimmune-type phenomenon in a small percentage of patients. Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), which can also manifest with gut lymphoid aggregates and an absence of small bowel plasma cells on enteric biopsies [18,19,20], is characterized by hypogammaglobulinemia and may occasionally present with diarrhea via a similar mechanism. However, we do not believe that CVID alone would explain our patients’ presentations given their rapid-onset symptoms and lack of CVID sequelae elsewhere. Regardless of the potential physiology, it is unclear why IEC-associated enterocolitis appears to occur in only a very small subset of patients following CAR-T therapy.

Our study has several limitations, most prominently the inability to definitively prove an association between CAR-T therapy and enterocolitis. While Fig. 2 clearly demonstrates the presence of infiltrating CAR T cells within the lamina propria of an affected patient, this does not conclusively demonstrate causality. Regardless, we believe that the timing of symptom onset and the lack of alternative etiologies both support a causal association with CAR-T therapy. The enterocolitis cases seen here are unlikely to be related to underlying MM given the relative rarity of acute-onset idiopathic diarrhea in patients who are not receiving lenalidomide or high-dose alkylating chemotherapy, which none of the patients in our analysis had recently received. While fludarabine and cyclophosphamide can potentially cause diarrhea, the timing of symptom onset (a median of 3 months after CAR-T infusion) argues against a toxicity of lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Infectious causes are unlikely given the negative workup in each case, both by stool testing and on tissue examination; however, CMV colitis can technically occur in the absence of CMV viremia or pathological identification on biopsies. While only one patient had a history of IBD in the remote past, it is possible but unlikely that an undiagnosed gut disorder such as IBD or irritable bowel syndrome may have been unmasked by the physiologic stress of CAR-T therapy. Finally, because we did not systematically evaluate all cases of diarrhea at every participating center, milder or self-limited cases may not have been reported and thus our collective incidence of 1.2% may potentially be an underestimate.

Other study limitations include the fact that not all patients had biopsy results available for review. Biopsy findings were not reviewed centrally, making it difficult to uniformly estimate histological patterns or proportions of immune cell subsets within biopsy specimens. The camelid VHH assay for cilta-cel is not uniformly available or validated in this setting. Finally, in contrast to 3 tentative cases of lymphoproliferative disorders presenting with diarrhea that our consortium has identified separately (Supplemental Table S1), T-cell lymphomas were not suspected in these 14 primary cases based on their morphologic and immunophenotypic features. While the stains in Fig. 2 do not definitively rule out a clonal population, the presence of both CD8-positive and CD8-negative T cells argues against a lymphoproliferative process. As boundaries between reactive lymphoid infiltrates and neoplastic lymphoid infiltrates are not always distinct, however, any suspicious infiltrate should undergo thorough evaluation by an expert hematopathologist. If a lymphoma is diagnosed, it should be reported to the FDA given the rare occurrence of T-cell lymphomas following BCMA CAR-T therapy [9, 21, 22]. Testing for the presence of CAR-positive T cells is reasonable to pursue in all cases of gut biopsies demonstrating lymphocytic infiltrates following CAR-T therapy. Nonetheless, our experience highlights the urgent need for our field to immediately recognize this entity as a unique IEC-associated toxicity. This is underscored by the fact that diarrhea persisted for almost a month before median corticosteroid initiation, in most cases well after patients had been discharged from their CAR-T treatment centers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, IEC-associated enterocolitis is a distinct but rare complication of CAR-T therapy characterized by non-bloody diarrhea typically beginning 1–3 months after infusion. Notably, this toxicity generally occurs after patients have been discharged from their CAR-T treatment facilities. Thorough diagnostic workup, including evaluation for potential T-cell malignancies, and appropriate management with an expert gastroenterologist are essential. Further research into the pathogenesis of this toxicity is critical to understand this novel complication, in particular because over a third of patients in our cohort died due to IEC-associated enterocolitis or the immune compromise associated with its treatment. In the interim, the early use of infliximab or vedolizumab may potentially hasten symptom resolution and lower reliance on high-dose corticosteroids during the post-CAR-T period.

Data availability

Deidentified data available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Rodriguez-Otero P, Ailawadhi S, Arnulf B, Patel K, Cavo M, Nooka AK, et al. Ide-cel or Standard Regimens in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl J Med. 2023;388:1002–14.

San-Miguel J, Dhakal B, Yong K, Spencer A, Anguille S, Mateos MV, et al. Cilta-cel or Standard Care in Lenalidomide-Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl J Med. 2023;389:335–47.

Cohen AD, Parekh S, Santomasso BD, Gallego Perez-Larraya J, van de Donk N, Arnulf B, et al. Incidence and management of CAR-T neurotoxicity in patients with multiple myeloma treated with ciltacabtagene autoleucel in CARTITUDE studies. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12:32.

Hines MR, Knight TE, McNerney KO, Leick MB, Jain T, Ahmed S, et al. Immune Effector Cell-Associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis-Like Syndrome. Transpl Cell Ther. 2023;9:438 e1–438 e16.

Santomasso BD, Gust J, Perna F. How I treat unique and difficult-to-manage cases of CAR T-cell therapy-associated neurotoxicity. Blood. 2023;141:2443–51.

Abu-Sbeih H, Tang T, Ali FS, Luo W, Neelapu SS, Westin JR, et al. Gastrointestinal Adverse Events Observed After Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2019;42:789–96.

Hashim A, Patten PEM, Kuhnl A, Ooft ML, Hayee B, Sanderson R. Colitis After CAR T-Cell Therapy for Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma Responds to Anti-Integrin Therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:e45–e46.

Zundler S, Vitali F, Kharboutli S, Volkl S, Polifka I, Mackensen A, et al. Case Report: IBD-like colitis following CAR T cell therapy for diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1149450.

Ozdemirli M, Loughney TM, Deniz E, Chahine JJ, Albitar M, Pittaluga S, et al. Indolent CD4+ CAR T-Cell Lymphoma after Cilta-cel CAR T-Cell Therapy. N. Engl J Med. 2024;390:2074–82.

Schneider BJ, Naidoo J, Santomasso BD, Lacchetti C, Adkins S, Anadkat M, et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:4073–126.

Elsallab, Ellithi M, Lunning MA M, D’Angelo, Ma C, Perales MA J, et al. Second primary malignancies after commercial CAR T-cell therapy: analysis of the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System. Blood. 2024;143:2099–105.

Perry AM, Warnke RA, Hu Q, Gaulard P, Copie-Bergman C, Alkan S, et al. Indolent T-cell lymphoproliferative disease of the gastrointestinal tract. Blood. 2013;122:3599–606.

Barone F, Patel P, Sanderson JD, Spencer J. Gut-associated lymphoid tissue contains the molecular machinery to support T-cell-dependent and T-cell-independent class switch recombination. Mucosal Immunol. 2009;2:495–503.

Spencer J, Sollid LM. The human intestinal B-cell response. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:1113–24.

Jahnsen FL, Baekkevold ES, Hov JR, Landsverk OJ. Do Long-Lived Plasma Cells Maintain a Healthy Microbiota in the Gut? Trends Immunol. 2018;39:196–208.

Mesin L, Di Niro R, Thompson KM, Lundin KE, Sollid LM. Long-lived plasma cells from human small intestine biopsies secrete immunoglobulins for many weeks in vitro. J Immunol. 2011;187:2867–74.

Landsverk OJ, Snir O, Casado RB, Richter L, Mold JE, Reu P, et al. Antibody-secreting plasma cells persist for decades in human intestine. J Exp Med. 2017;214:309–17.

Daniels JA, Lederman HM, Maitra A, Montgomery EA. Gastrointestinal tract pathology in patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID): a clinicopathologic study and review. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1800–12.

Jorgensen SF, Reims HM, Frydenlund D, Holm K, Paulsen V, Michelsen AE, et al. A Cross-Sectional Study of the Prevalence of Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Pathology in Patients With Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1467–75.

van Schewick CM, Lowe DM, Burns SO, Workman S, Symes A, Guzman D, et al. Bowel Histology of CVID Patients Reveals Distinct Patterns of Mucosal Inflammation. J Clin Immunol. 2022;42:46–59.

Banerjee R, Poh C, Hirayama AV, Gauthier J, Cassaday RD, Shadman M, et al. Answering the “Doctor, can CAR-T therapy cause cancer?” question in clinic. Blood Adv. 2024;8:895–8.

Harrison SJ, Nguyen T, Rahman M, Er J, Li J, Li K, et al. CAR+ T-Cell Lymphoma Post Ciltacabtagene Autoleucel Therapy for Relapsed Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Blood. 2023;142:6939.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all the patients and their caregivers involved in this study. The authors would also like to acknowledge the research coordinators and hematopathology teams at each institution who assisted with data collection and interpretation. The authors would also like to acknowledge Tissue Core and the Advanced Analytical and Digital Laboratory at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, an NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292), for their contribution in the multiplex immunofluorescence quantitative digital image analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GGF, RB, and CSF wrote the first or subsequent drafts of the manuscript. All authors (GGF, RB, CSF, JS, CMS, JVN, LL, SFP, ANJ, KNN, MVM, RCB, JYS, LM, JMG, SS, AMSC, NMK, KKP, KGS, RF, CF, PMV, SR, CRV, SA, JLW, AJC, DWS, FLL, YL, YW, DKH) contributed substantially to data collection and/or manuscript revision. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

RB reports consulting: Adaptive Biotech, BMS, Caribou Biosciences, Genentech, GSK, Janssen, Karyopharm, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, Sanofi, SparkCures; Research: Abbvie, BMS, Janssen, Novartis, Pack Health, Prothena, Sanofi. RF reports consulting: AbbVie, Adaptive, Amgen, Apple, BMS/Celgene, GSK, Janssen, Karyopharm, Pfizer, RA Capital, Regeneron, Sanofi; Scientific Advisory Board: Caris Life Sciences; Board of Directors: Antengene; Patents for certain FISH tests in MM. CF reports consulting: Janssen; research: Regeneron, Janssen; stock ownership: Affimed. PMV reports consulting: Abbvie, Astra Zeneca, BMS, GSK, Janssen, Karyopharm, Lava Therapeutics, Regeneron, Sanofi; research: Abbvie, Janssen, Regeneron. SDR reports honoraria: Janssen, BMS; steering committee involvement, Gracell Therapeutics, BMS; research support, Janssen, BMS, C4 Therapeutics, Gracell Therapeutics, Heidelberg Pharma; consulting: Genentech, Janssen, BMS. JYS reports consulting: Kite, Immpact Bio. LL reports consulting: Allogene, Sanofi. SFP reports Consulting: Cartography Biosciences; Scientific Advisory Board: Leica Biosystems. JLW reports consulting: Adaptive. AJC reports consulting: BMS, Adaptive; Research: Adaptive Biotechnologies, Harpoon, Nektar, BMS, Janssen, Sanofi, AbbVie. DWS reports consulting: GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Sanofi, Abbvie, Bristol Myer Squibb, Pfizer, Bioline, Arcellx, AstraZeneca, Genentech; Research: Gilead, Pfizer, Janssen, Bioline, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Amgen, Cantex, Arcellx, Roche; Steering Committee: Janssen; Data safety and monitoring: Karyopharm, and Independent Review Committee: Parexel. FLL reports a consulting or advisory role for Allogene, Amgen, Bluebird Bio, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Calibr, Cellular Biomedicine Group, Cowen, ecoR1, Emerging Therapy Solutions Gerson Lehman Group, GammaDelta Therapeutics, Iovance, Janssen, Kite, a Gilead Company, Legend Biotech, Novartis, Umoja, and Wugen; research funding from Allogene, Kite, and Novartis; and patents, royalties, other intellectual property in the field of cellular immunotherapy. P.V reports consulting or advisory role for Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Lava Therapeutics, Sanofi, Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline; Research funding from Abbvie, Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline, and TeneoBio; Travel, accommodations, and expenses from Sanofi. DKH reports consulting: BMS, Janssen, legend Biotech, Pfizer, Karyopharm; Research: BMS, Karyopharm, Adaptive Biotechnologies, and Pentecost Myeloma Research Center. The remaining authors have no interests to disclose.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for participation within the Consortium at each participating center. Patients signed informed consent at the time of CAR-T referral at each center. No identifiable data or images were shared between centers, and no identifiable data or images are present in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fortuna, G.G., Banerjee, R., Savid-Frontera, C. et al. Immune effector cell-associated enterocolitis following chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 14, 180 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-024-01167-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-024-01167-8

This article is cited by

-

Antibody-Drug Conjugates, T-Cell Engager Bispecific Antibodies and Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells for Multiple Myeloma: What’s the Current Status?

Targeted Oncology (2026)

-

CD4+ T cells mediate CAR-T cell-associated immune-related adverse events after BCMA CAR-T cell therapy

Nature Medicine (2026)

-

CAR-T for multiple myeloma: practice pearls

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2025)

-

CAR T-cells in multiple myeloma: the race to the start line

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2025)

-

Managing IEC-associated enterocolitis following CAR-T therapy in multiple myeloma

Blood Cancer Journal (2025)