Abstract

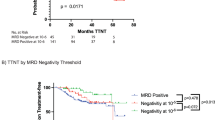

Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) has been the prime consolidative strategy to increase the depth and duration of response in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM), albeit with short- and long-term toxicities. Minimal residual disease (MRD) is an important early response endpoint correlating with clinically meaningful outcomes and may be used to isolate the effect of ASCT. We report the impact of ASCT on MRD burden and generate a benchmark for evaluation of novel treatments as consolidation. We collected MRD by next generation sequencing (NGS; clonoSEQ®) post induction and post-ASCT in consecutive patients (N = 330, quadruplet, N = 279; triplet, N = 51). For patients receiving quadruplets, MRD < 10−5 post-induction was 29% (MRD < 10−6 15%) increasing to 59% post-ASCT (MRD < 10−6 45%). Among patients with MRD > 10−5 post-induction, ASCT lowered the MRD burden>1 log10 for 69% patients. The use of quadruplet induction (vs. triplet) did not reduce the effect of ASCT on MRD burden. Reduction in MRD burden with ASCT was most pronounced in patients with high-risk chromosome abnormalities.

This dataset provides granular data to delineate the impact of ASCT on MRD as legacy consolidative strategy in NDMM and provides an important benchmark for evaluation of efficacy of TCRT as experimental consolidative strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple Myeloma is a plasma cell malignancy characterized by anemia, bone lesions, hypercalcemia, renal failure and predisposition to infections. The outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) continue to improve owing to the tremendous improvement in understanding of disease biology leading to progress in therapeutics and supportive care measures [1, 2]. The use of anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies (anti-CD38 mAb), proteasome inhibitors (PI), immunomodulatory agents (IMiDs) and corticosteroids (dex) in quadruplet combinations, particularly when followed by upfront autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), resulted in unprecedented depth and duration of response in NDMM [3,4,5,6]. However, NDMM is quite heterogeneous in biology, presentation, and response to therapy [7, 8]. Current therapeutic standards therefore are insufficient for some patients and may be excessive for others.

The availability of efficacious therapies has catalyzed the need to develop more sophisticated methods to detect residual disease and understand treatment response. With our current triplet and quadruplet combinations, most patients will achieve deep responses using traditional paraprotein based testing, and discriminating outcomes is challenging. In this setting measurable residual disease (MRD) has been shown to be one of the most important dynamic prognostic markers for progression free (PFS) and overall survival (OS) [9]. In comparison to traditional measurement of paraprotein (surrogate) to characterize disease response, MRD provide a direct estimation of tumor burden (clonal plasma cells). Indeed, Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) recommended acceptance of MRD as an endpoint for accelerated drug approval to the FDA due to robust individual-level surrogacy for PFS and OS, along with moderate to strong trial-level surrogacy for PFS [10].

ASCT has been a prime consolidative strategy for patients with transplant eligible NDMM. However, while it helps improve the depth, including MRD negativity, and duration of response in NDMM, it has short- and long-term toxicities. MRD provides a novel opportunity to accurately characterize the incremental benefit of ASCT on depth of response. By assessing the pre- and post-ASCT MRD, we have a direct estimation of clone size as opposed to paraprotein measurements which can be fraught with challenges such as heterogeneity in paraprotein clearance and inaccurate characterization of the disease burden. Utilizing MRD therefore helps isolate the effect of ASCT independent of induction regimen and can serve as a benchmark for the development of alternative consolidations strategies. The remarkable efficacy of immunotherapy in relapsed MM has led to their development in earlier lines of therapy. The premise is to improve the toxicity and efficacy balance in the setting of lower burden and less refractory disease as more common early in the disease course. T cell redirecting therapy (TCRT) including bispecific antibodies and chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapies are being investigated as an alternative and/or adjunctive strategy with ASCT in NDMM. However, to understand their relative efficacy, a clear benchmark for expected change in clone size and MRD burden for the ASCT consolidative strategy is vital for appropriate comparisons.

We sought to isolate the effect of ASCT, as legacy consolidative therapy in NDMM, on MRD burden and generate a benchmark for evaluation of TCRT in this setting.

Methods

We collected MRD status by next generation sequencing (NGS; clonoSEQ®) irrespective of IMWG response post triplet (PI+IMiD+dex) and quadruplet (triplet + anti-CD38 mAb) induction and 60–100 days after ASCT in consecutive patients at one large volume myeloma program along with participants of two single arm phase 2 trials with quadruplet induction followed by ASCT. We analyzed MRD at a threshold of 10−5 and 10−6 and as a continuous variable. We report the effect of ASCT on MRD negativity rates and quantitative disease burden according to type of induction therapy and cytogenetic subsets.

Patients and study design

We analyzed data from two clinical trials: Monoclonal Antibody-Based Sequential Therapy for Deep Remission in Multiple Myeloma (MASTER; NCT03224507) and Minimal Residual Disease Response-adapted Deferral of Transplant in Dysproteinemia (MILESTONE; NCT NCT04991103). MASTER is a single arm, phase 2 multicenter study of MRD guided quadruplet therapy for NDMM, while MILESTONE is a single center, phase 2 study evaluating the use of MRD for decision to proceed with ASCT following quadruplet induction [3, 11, 12]. We also included consecutive patients not participating in a clinical trial and receiving ASCT for NDMM following induction with triplet and quadruplet therapy as standard of care as a part of institutional guidance for management of NDMM who had pre and post ASCT MRD results. All patients collected autologous stem cells shortly after completion of triplet or quadruplet induction using granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, with or without plerixafor as mobilization per institutional policy. Patients received high dose melphalan (140–200 mg/m2 at investigator discretion) followed by ASCT.

The following abnormalities when present by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) constituted high risk cytogenetic abnormalities (HRCA): gain/amplification 1q, t(4;14), t(14;16), and del(17p) [13]. Patients were grouped according to the number of HRCA present in the clonal plasma cells (0, 1, or 2 + ).

MRD assessment

We collected the “first pull” bone marrow aspirate for MRD assessment using next-generation sequencing (NGS; ClonoSEQ® platform; Adaptive Biotechnologies, Seattle, WA) upon completion of induction therapy and 60–100 days after ASCT. We performed MRD assessment in all patients, simultaneously with and not influenced by IMWG response assessment, and reported MRD defined by thresholds of 10−5 and 10−6 at those timepoints. For patients with MRD ≥ 10−5 post induction, we describe quantitative relative changes in MRD burden, expressed by log10 of the relative reduction in MRD burden with AHCT, defined as log10(MRD pre-AHCT/MRD post-AHCT). MRD assessment and reporting aligns with the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) consensus criteria for response and MRD assessment in MM, and the international harmonization in performing and reporting MRD assessment in MM trials [14, 15].

Study oversight

The clinical trials were conducted under the University of Alabama at Birmingham O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center Data and Safety Monitoring Plan and in accordance with the International Council for Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and the principles of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent for participation. Institutional review boards approved the protocol and related documents. The clinical trials are registered in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03224507; NCT04991103). Amgen and Janssen provided material support for the MASTER clinical trial. The American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant funds the MILESTONE trial internally. The non-clinical trial patients provided written informed consent to participate in an institutional database.

Statistics

We compared proportions using Fisher’s exact test and numerical variables across groups using the Mann–Whitney U test. A two-sided p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS (v27.0).

Results

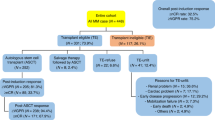

We identified 330 patients with pre- and post-ASCT MRD data. The median age of the entire cohort was 61 years (range 30-79), 185 (56%) males, 215 (65%) Non-Hispanic Whites (NHW). Three hundred and seventeen of the 330 (96%) patients had cytogenetic information at the time of diagnosis, 106 (33%) had 1 HRCA and 44 (14%) had 2 + HRCA. Of the 330 patients, 124 (38%) were clinical trial participants. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Induction and ASCT effect on MRD

Of the 330 patients, 279 (85%) received quadruplets during induction therapy. The proteasome inhibitor in the quadruplet was carfilzomib in 113 (41%) and bortezomib on the remaining patients. The median number of quadruplets cycles prior to ASCT was 4 cycles (range 4–12). The best response to quadruplet induction therapy was stable disease (SD) in one patient, partial response (PR) in 50 (18%), very good partial response (VGPR) in 141 (51%), complete response (CR) in 17 (6%) and stringent complete response (sCR) in 70 patients (25%). Following ASCT, the IMWG best responses included 18 (6%) PR, 105 (38%) VGPR, 35 (13%) CR and 119 (43%) sCR (Supplementart Fig. 2). Two patients experienced progressive disease at or within 100 days following ASCT. Granular data on transition across MRD strata with ASCT is displayed in Fig. 1. Among patients receiving quadruplet induction, 82 (29%) achieved MRD < 10−5 following induction therapy, and 165 (59%) had MRD < 10−5 following ASCT. There were 42 patients (15%) who had achieved MRD < 10−6 post quadruplet induction, increasing to 125 (45%) post ASCT (Fig. 1, panel A). Among the 197 quadruplet patients with MRD ≥ 10−5 post-induction, ASCT lowered the MRD burden ≥ 1 log10 in 135 (68.5%) (Fig. 1, panel C). Patients with high disease burden (MRD ≥ 10−3) following induction with quadruplet were less likely to convert to MRD < 10−5 with ASCT (Fig. 1, panel A). A minority of patients with MRD > 10−3 converted to MRD < 10−5 (20%) and MRD < 10−6 (17%) with ASCT.

Sankey plots showing change in MRD strata with ASCT in (A) Patients treated with quadruplet induction, (B) patients treated with triplet induction and. C Quantitative changes in MRD burden after ASCT in patients with MRD ≥ 10−5 post induction, based on exposure to CD38 monoclonal antibody in induction.

Of the 330 patients, 51 (15%) received triplet therapy during induction. For patients receiving triplet induction, the best IMWG response following induction was PR in 18 (35%), VGPR in 22 (43%), CR in 5 (10%) and sCR in 6 (12%). Following ASCT, the IMWG best responses included 5 (10%) PR, 25 (49%) VGPR, 13 (25%) CR and 8 (16%) sCR (supplemental figure 2). Among triplet patients, the rate of MRD < 10−5 post-induction was 16% increasing to 41% post-ASCT. The rate of MRD < 10−6 post induction was 4% increasing to 24% post ASCT (Fig. 1, panel B). Among patients with MRD ≥ 10−5 post-induction, ASCT lowered the MRD burden ≥ 1 log10 in 56% patients (Fig. 1, panel C). The incremental decrease in disease burden with ASCT was similar among patients who received triplets and quadruplets induction (Fig. 1, panel C).

Overall, 69 (21%) patients received reduced dose melphalan (140 mg/m2) as ASCT conditioning regimen per investigator discretion. Melphalan dose intensity did not influence the incremental reduction in disease burden with ASCT (Supplemental figure 1).

Cytogenetic risk and ASCT effect on MRD

Among patients who received quadruplet induction (N = 279), 270 had baseline cytogenetic information available at the time of diagnosis, 97 (36%) had 1 HRCA, 40 (15%) had 2 + HRCA. Following quadruplet induction therapy, MRD < 10−5 was 19%, 31% and 28% improved to 53%, 66% and 65% post-ASCT for patients with 0, 1 and 2 + HRCA, respectively (Fig. 2). The MRD < 10−6 post induction was 17%, 14%, 10% following induction, improving to 41%, 50%, 48% post-ASCT for patients with 0, 1 and 2 + HRCA, respectively. Patients with ultra-high-risk MM (2 + HRCA) derived greatest reduction in disease burden with ASCT (Figs. 2 and 3).

Among all patients with MRD ≥ 10−5 post induction, ASCT lowered the MRD burden ≥ 1 log10 for 60%, 72% and 81% of patients with 0, 1 and 2 + HRCA, respectively. Similar results were seen in the subset of patients who received quadruplet induction (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Our study isolates the impact of ASCT on disease burden using direct quantification of clonal plasma cells rather than a surrogate biomarker (paraprotein). We provide granular information on reduction in disease burden in different cytogenetic subsets and show that patients continue to experience a similar magnitude of reduction in disease regardless of incorporation of anti-CD38 mAb in induction. In aggregate, our study establishes a benchmark for the design of future clinical trials by defining expected MRD trajectories with quadruplet induction followed by ASCT.

In NDMM, MRD negativity has been associated with longer PFS and OS, with deeper MRD (<10−6) responses being more discriminatory in delineating patient outcomes (compared to 10−5 or greater) [9, 10, 16]. Given its prognostic significance, MRD was reviewed favorably as an early clinical endpoint to support the accelerated approval of novel therapies alongside confirmatory demonstration of longer-term traditional endpoints [10]. It is being routinely evaluated in the clinic among patients with NDMM and those achieving MRD negativity experience improved long term outcomes. For decades, ASCT has been a cornerstone of anti-plasma cell directed therapy with impressive efficacy with well-known short-term toxicities [17, 18]. However, with deeper understanding of disease evolution and biology, we are beginning to unpack the long-term toxicities of this therapy in a population that is likely to live longer with improved therapeutics [19]. Several datasets have provided insight into its efficacy particularly in patients with ultra-high-risk MM (2 + HRCA) and our data again supports a large effect size for this subset [11, 13, 20,21,22]. Greater benefit among patients with ultra-high risk MM is likely due to the use of alkylator therapy (melphalan) as an additional non-cross-resistant approach to reduce the potentially more proliferative disease not eliminated by novel agents in a complementary manner. In fact, log kill hypothesis, which is expected for melphalan, hypothesizes that fractional killing is independent of initial disease burden demonstrated by similar magnitude of disease burden reduction irrespective of monoclonal antibody use in induction. However, the role, timing and value of ASCT for all eligible patients, particularly those with standard risk MM and single HRCA MM where available induction strategies have provided deep responses and improved outcomes is being questioned. Establishing an MRD trajectory benchmark for the current standard of quadruplet induction and ASCT provides a tool for sample size estimation and optimal design of studies deploying novel therapies in addition to or in replacement of ASCT.

Quadruplet therapies have significantly improved the PFS and OS of patients with newly diagnosis multiple myeloma for both transplant eligible and ineligible patients [4,5,6, 23,24,25]. Several large, randomized studies in transplant eligible NDMM have evaluated the quadruplet induction, ASCT and post-ASCT quadruplet consolidation followed by maintenance (such as CASSIOPEIA, GRIFFIN, PERSEUS). However, the magnitude of incremental benefit and isolated effect of ASCT in disease control remains not well described since MRD is assessed following post-ASCT consolidation and not immediately following ASCT and exact effect of the ASCT procedure on disease burden is unclear [4]. Additionally, there is a lot of heterogeneity among the reporting of MRD across different trials, differences in testing methodology (flow cytometry vs. NGS), numbers of cycles of induction/consolidation, and response category of patients in whom MRD was assessed. The recently reported randomized phase 3 ISKIA study provided more granular data in this setting. Transplant eligible patients with NDMM patients were enrolled and randomized to receive a carfilzomib containing quadruplet with or without CD38 mAb, followed by ASCT. In ISKIA, pre-ASCT MRD < 10−5 was 45% increasing to 64% post ASCT (MRD < 10−6 increasing from 27% to 52% post ASCT) compared to our report of 29% pre-ASCT increasing to 59% post-ASCT (MRD < 10−6 15% increasing to 45% post ASCT). Compared to ISKIA, our study is larger with more granular data in quadruplet treated patients in a population which is more representative of practice patterns in the US (older patients, bortezomib as the proteasome inhibitor).

We also tested MRD on all consecutive patients regardless of IMWG response to capture. This leads to important observations. For instance, patients with high disease burden (MRD > 10−3) following quadruplet therapy, a third of the population, 55% of which were in ≥ VGPR and 7% in ≥ CR, are unlikely to reach MRD < 10−5 and MRD < 10−6 with ASCT alone and are in greatest need for novel approaches.

Our analysis has several limitations. Our population is more heterogenous than typical clinical trial populations both in demographics and in regimen used for induction therapy. We mitigated that by emphasizing the analysis in patients receiving quadruplet induction. We only included patients who were MRD evaluable using NGS, those patients were baseline samples could not be retrieved or clonogenic sequences could not be identified were not included. Yet another inherent limitation is that the data is conditional upon patients proceeding to ASCT after induction therapy and did not include patients who could not proceed due to toxicity, or early disease progression during induction precluding upfront ASCT. We did not attempt to correlate MRD endpoints before or after ASCT with long term follow up. While this correlation has been unambiguously demonstrated, the trials and clinical practice included in this analysis adapted the post ASCT to the very MRD endpoint, either by intensification or deintensification of therapy, invalidating or at least blurring such analysis. A small number of patients in this study were treated on a clinical trial protocol where decision to proceed ASCT was deferred among patients achieving MRD < 10−5 post induction following quadruplet induction. While the absolute number of patients who achieved this milestone from very small, there is a small downward bias in estimation of true pre-ASCT MRD rate.

TCRT and other drug classes such as CELMoDs™ have demonstrated outstanding depth and duration of response in relapsed MM [26,27,28,29,30]. Their unparalleled efficacy in the multiply relapsed setting has catalyzed their rapid movement into earlier lines with hope of improving durability of response and the potential for curative approach to NDMM [31]. Additionally, patients such as those who have functional high-risk disease without significant response or persistent MRD burden following treatment with quadruplets with and without ASCT may be candidates for treatment intensification [7]. Several studies are ongoing and being planned to directly compare these head-to-head against ASCT (NCT05257083) and others as post-ASCT consolidation therapies (NCT05243797, NCT05317416, NCT05827016, NCT06045806, NCT04133636, NCT05434689). In a newly framed landscape where MRD will be employed as endpoint for accelerated drug approval, our study provides granular, strata-specific benchmark to design trials testing TCRT in NDMM.

Data availability

The de-identified dataset generated during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Paquin AR, Kumar SK, Buadi FK, Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, et al. Overall survival of transplant eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: comparative effectiveness analysis of modern induction regimens on outcome. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8:1–7.

Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Gertz MA, Buadi FK, Pandey S, et al. Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma: changes in early mortality and outcomes in older patients. Leukemia. 2014;28:1122–8.

Costa LJ, Chhabra S, Medvedova E, Dholaria BR, Schmidt TM, Godby KN, et al. Daratumumab, Carfilzomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone with minimal residual disease response-adapted therapy in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2021;40:2901–12.

Moreau P, Attal M, Hulin C, Arnulf B, Belhadj K, Benboubker L, et al. Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (CASSIOPEIA): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394:29–38.

Sonneveld P, Dimopoulos MA, Boccadoro M, Quach H, Ho PJ, Beksac M, et al. Daratumumab, Bortezomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone for Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2024:390:301–13.

Voorhees PM, Sborov DW, Laubach J, Kaufman JL, Reeves B, Rodriguez C, et al. Addition of daratumumab to lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for transplantation-eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (GRIFFIN): final analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10:e825–37.

Ravi G, Bal S, Joiner L, Giri S, Sentell M, Hill T, et al. Subsequent therapy and outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma experiencing disease progression after quadruplet combinations. Br J Haematol. 2024;204:1300–6.

Banerjee R, Cicero KI, Lee SS, Cowan AJ. Definers and drivers of functional high-risk multiple myeloma: insights from genomic, transcriptomic, and immune profiling. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1240966.

Munshi NC, Avet-Loiseau H, Rawstron AC, Owen RG, Child JA, Thakurta A, et al. Association of minimal residual disease with superior survival outcomes in patients with multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:28–35.

Landgren O, Prior TJ, Masterson T, Heuck C, Bueno OF, Dash AB, et al. EVIDENCE meta-analysis: evaluating minimal residual disease as an intermediate clinical endpoint for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2024;144:359–67.

Costa LJ, Chhabra S, Medvedova E, Dholaria BR, Schmidt TM, Godby KN, et al. Minimal residual disease response-adapted therapy in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MASTER): final report of the multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10:e890–901.

Bal S, Zumaquero E, Ravi G, Godby K, Giri S, Denslow A, et al. Immune profiling of Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma (NDMM) treated with quadruplet induction and Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation (ASCT) and comparison with achievement of Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) negativity. Blood. 2023;142:4685.

Gay F, Musto P, Rota-Scalabrini D, Bertamini L, Belotti A, Galli M, et al. Carfilzomib with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone or lenalidomide and dexamethasone plus autologous transplantation or carfilzomib plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone, followed by maintenance with carfilzomib plus lenalidomide or lenalidomide alone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (FORTE): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1705–20.

Costa LJ, Derman BA, Bal S, Sidana S, Chhabra S, Silbermann R, et al. International harmonization in performing and reporting minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma trials. Leukemia. 2021;35:18–30.

Kumar S, Paiva B, Anderson KC, Durie B, Landgren O, Moreau P, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e328–46.

Perrot A, Lauwers-Cances V, Corre J, Robillard N, Hulin C, Chretien ML, et al. Minimal residual disease negativity using deep sequencing is a major prognostic factor in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2018;132:2456–64.

Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Hulin C, Leleu X, Caillot D, Escoffre M, et al. Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone with Transplantation for Myeloma. N. Engl J Med. 2017;376:1311–20.

Richardson PG, Jacobus SJ, Weller EA, Hassoun H, Lonial S, Raje NS, et al. Triplet therapy, transplantation, and maintenance until progression in myeloma. N. Engl J Med. 2022;387:132–47.

Maura F, Weinhold N, Diamond B, Kazandjian D, Rasche L, Morgan G, et al. The mutagenic impact of melphalan in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2021;35:2145–50.

Bal S, Godby K, Chhabra S, Medvedova E, Cornell RF, Hall AC, et al. Impact of Autologous Hematopoetic Stem Cell Transplant (AHCT) on Measurable Residual Disease (MRD) by Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) in the Setting of Daratumumab, Carfilzomib, Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone (Dara-KRd) Quadruplet Induction. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2020;26:S24.

Hari P, Pasquini MC, Stadtmauer EA, Fraser R, Fei M, Devine SM, et al. Long-term follow-up of BMT CTN 0702 (STaMINA) of postautologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (autoHCT) strategies in the upfront treatment of multiple myeloma (MM). JCO. 2020;38:8506.

Cavo M, Gay F, Beksac M, Pantani L, Petrucci MT, Dimopoulos MA, et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation versus bortezomib–melphalan–prednisone, with or without bortezomib–lenalidomide–dexamethasone consolidation therapy, and lenalidomide maintenance for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (EMN02/HO95): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e456–68.

Facon T, Kumar S, Plesner T, Orlowski RZ, Moreau P, Bahlis N, et al. Daratumumab plus Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone for Untreated Myeloma. N. Engl J Med. 2019;380:2104–15.

Mateos MV, Dimopoulos MA, Cavo M, Suzuki K, Jakubowiak A, Knop S, et al. Daratumumab plus Bortezomib, Melphalan, and Prednisone for Untreated Myeloma. N. Engl J Med. 2018;378:518–28.

Moreau P, Hulin C, Perrot A, Arnulf B, Belhadj K, Benboubker L, et al. Bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab and followed by daratumumab maintenance or observation in transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: long-term follow-up of the CASSIOPEIA randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2024;25:1003–14.

Berdeja JG, Madduri D, Usmani SZ, Jakubowiak A, Agha M, Cohen AD, et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet. 2021;398:314–24.

Munshi NC, Anderson LD, Shah N, Madduri D, Berdeja J, Lonial S, et al. Idecabtagene Vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl J Med. 2021;384:705–16.

Moreau P, Garfall AL, van de Donk NWCJ, Nahi H, San-Miguel JF, Oriol A, et al. Teclistamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl J Med. 2022;387:495–505.

Lesokhin AM, Tomasson MH, Arnulf B, Bahlis NJ, Miles Prince H, Niesvizky R, et al. Elranatamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: phase 2 MagnetisMM-3 trial results. Nat Med. 2023;29:2259–67.

San-Miguel J, Dhakal B, Yong K, Spencer A, Anguille S, Mateos MV, et al. Cilta-cel or standard care in lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:335–47.

Cohen AD, Mateos MV, Cohen YC, Rodriguez-Otero P, Paiva B, van de Donk NWCJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of cilta-cel in patients with progressive multiple myeloma after exposure to other BCMA-targeting agents. Blood. 2023;141:219–30.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the multiple myeloma survivor and patient advocate Yelak Biru and Jim Omel for their input on trial design and conduct. They owe the idealization and completion of this study to the patients’ and research staff’s shared commitment to improve the lives of future patients with myeloma.

Funding

Supported in part by Amgen, Janssen, and American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant (IRG-21-140-62).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB conceptualized and designed the study, contributed patients, assembled and analyzed the data and wrote the paper. LJC conceptualized and designed the study, contributed patients, assembled and analyzed the data and wrote the paper. TM collected the data and wrote the paper. GR provided patient data and edited the manuscript. KG provided patient data and edited the manuscript. RS provided patient data and edited the manuscript. BD provided patient data and edited the manuscript. SG provided patient data and edited the manuscript. BD provided patient data and edited the manuscript. NSC provided patient data and edited the manuscript. VR assisted with MRD data and edited the manuscript. All authors provided final approval of manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

SB received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Beigene and honoraria from AbbVie, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen and MJH Lifesciences. RS served as a consultant or in an advisory role for Sanofi-Aventis, Janssen Oncology, and Oncopeptides; and received research funding from Sanofi. BD has received honoraria and served as a consultant and on the Speakers Bureau for Arcellx, Genentech, GSK, Janssen, Karyopharm, Pfizer, and Sanofi. BD: Institutional research funding: Janssen, Angiocrine, Pfizer, Poseida, MEI, Orcabio, Wugen, Allovirm Adicet, BMS, Molecular templat. Consultancy/Advisor: MJH BioScience, Janssen, ADC therapeutics, Gilead/Kite, Autotus, Poseida, Accrotech. SG received consulting or advisory Role: Janssen, Sanofi, Research funding: Janssen, Sanofi, PackHealth, CareVive; Grant R. Williams, Honoraria: Bayer, Takeda. LJC received research funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech and honoraria from Amgen, Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Sanofi and Pfizer. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients included in this analysis have provided informed consent for participation in the study. The study was conducted in compliance with International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) and Good Clinical Practices (GCPs). The protocol was approved by the respective Institutional Review Board or ethics committee at each of the participating institutions (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL; Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI; Wisconsin Institutes for Medical Research, Madison, WI; Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR; Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN; all in the USA). All subjects provided documented informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All authors had access to the data and contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results. The authors confirm the accuracy and completeness of the data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bal, S., Magnusson, T., Ravi, G. et al. Establishing measurable residual disease trajectories for patients on treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma as benchmark for deployment of T-cell redirection therapy. Blood Cancer J. 15, 73 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01252-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01252-6