Abstract

Venetoclax showed promising activity in a small phase II trial in relapsed/refractory Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM). To report the clinical activity of venetoclax and prognostic factors associated with outcomes in a larger cohort, we retrospectively identified 76 patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL)/WM treated with venetoclax monotherapy at nine US medical centers. The median age at venetoclax treatment initiation was 66 years. MYD88, CXCR4, and TP53 mutations were detected in 65 (94%), 23 (40%), and 10 (22%) patients, respectively. The median number of prior lines of treatment was 3, including covalent BTK inhibitor in 82% and alkylating agent in 71% of patients. The overall and major response rates to venetoclax were 70% and 63%, respectively. The median and 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) were 28.5 months and 57%, respectively. The median and 2-year overall survival were not reached and 82%, respectively. Prior treatment with BTK inhibitor was the only factor associated with PFS in multivariate analysis (hazard ratio 2.97, p = 0.012). Venetoclax dose interruptions and/or reductions occurred in 27 patients (41%). Five patients (7%) developed laboratory tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), including 3 (4%) with clinical TLS. Venetoclax resulted in a high response rate and a prolonged PFS in patients with heavily pretreated LPL/WM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström macroglobulinemia (LPL/WM) is an uncommon indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by recurrent relapses and progressively shortening responses or resistance to subsequent treatments. Although most patients respond to treatment with chemoimmunotherapy, proteasome inhibitors, or Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi), relapses are inevitable, and more active therapies for patients with relapsed or refractory LPL/WM are needed [1].

The BH3-mimetic venetoclax inhibits the antiapoptotic protein BCL2, which is overexpressed in LPL/WM, and induces apoptosis in lymphoplasmacytic cell lines regardless of CXCR4 mutation status [2]. Venetoclax has shown significant clinical activity in various B-cell lymphoid malignancies, including LPL/WM [3, 4]. In a phase II trial of venetoclax monotherapy (800 mg daily for two years) in 32 patients with relapsed or refractory WM, including 16 previously treated with BTKi, the overall (ORR), major, and minor (MR) response rates were 84%, 81%, and 19%, respectively [4]. With a median follow-up of 33 months, the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 30 months. Treatment with venetoclax was safe, with the only recurring grade ≥3 adverse event being neutropenia (45%), and only one episode of neutropenic fever. Laboratory tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) was reported in only one patient (without clinical TLS) [4]. Based on these results, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines endorsed venetoclax for treating relapsed/refractory WM in 2022 [5].

In this study, we sought to evaluate the clinical activity and safety of venetoclax and identify factors associated with outcomes in a larger cohort of patients with relapsed or refractory LPL.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed records of patients aged ≥18 years with a diagnosis of LPL treated at nine US medical centers between January 2010 and December 2022. We identified patients treated with venetoclax monotherapy in the context of a clinical trial or through commercial supply. We collected clinical, laboratory, pathologic, and outcome data for each patient at diagnosis and before venetoclax treatment initiation. Data on hemoglobin (Hb) levels, absolute neutrophil counts (ANC), and serum immunoglobulin levels were collected at serial time points during treatment with venetoclax. The primary outcome was to determine the overall response rate (ORR), which included MR, partial response (PR), very good partial response (VGPR), and complete response (CR). Treatment responses were determined by the local investigator, according to the 11th International Workshop on Waldenström Macroglobulinemia (IWWM-11) criteria for patients with WM, or based on serum monoclonal protein levels, bone marrow involvement, and/or imaging for patients with non-IgM LPL [6]. Secondary objectives were to determine the major response rate (PR or better), time to best response, PFS, overall survival (OS), and venetoclax safety, as well as predictors of ORR, major response, PFS, and OS. We defined laboratory and clinical TLS per the Cairo-Bishop criteria [7].

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize patient characteristics before venetoclax initiation with the median and range presented for continuous variables, and frequency count and percentage provided for categorical variables. We used univariate logistic regression models to estimate the association between patient characteristics and ORR. PFS was calculated from the time of venetoclax initiation to either progression or death, and OS from the time of venetoclax initiation to death due to all causes; patients without events were censored at the time of the last follow-up. PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate analyses (MVAs) were performed using Cox proportional-hazard models to identify predictors of PFS and OS. The stepwise selection, with p < 0.15 for entry criteria, was used to build the final MVA model. All analyses were conducted using SAS, 9.4 (2016 by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board (incorporating the ethics committee) at each participating site. Irrespective of this analysis, all patients provided informed consent before receiving treatment. This study is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Patient and disease characteristics

Seventy-six patients were included. At the time of venetoclax treatment start (Table 1), the median age was 66 years (range, 38-91), the median Hb level was 10 g/dL (range, 6–16), and the median serum IgM level was 2409 mg/dL (range, 5–9300). Sixty-two (89%) patients had WM and eight (11%) had non-IgM LPL (IgG/IgA serum monoclonal protein in 6 and absent in 2) (missing n = 6). Forty-seven patients (65%) had a bone marrow biopsy done within 3 months before starting venetoclax, with a median bone marrow involvement by lymphoma of 60% (44% with ≥50% involvement, missing n = 4). Among patients with available data, MYD88, CXCR4, and TP53 mutations were detected in 65 (94%, missing n = 7), 23 (40%, missing n = 19), and 10 (22%, missing n = 31) patients, respectively.

Prior treatments

The median number of lines of treatment before venetoclax was 3 (range, 1-11; 63% ≥3) which included an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody in 67 patients (88%), covalent BTKi in 62 (82%), proteasome inhibitor in 45 (59%), bendamustine in 44 (58%), and cyclophosphamide in 32 (42%) (Table 2). Nineteen patients (28%) had refractory disease (defined as stable [SD] or progressive disease [PD]) while receiving the last therapy before venetoclax (missing n = 9). The ORR to the BTKi before venetoclax was 77% (CR 4%, VGPR 21%, PR 32%, MR 20%) (missing n = 6). Treatment with BTKi lasted for a median of 14.3 months (range, 0.5-119.5) and was stopped because of PD in 66% and toxicity in 34% of patients. BTKi was the most frequent treatment used immediately before venetoclax (39 patients, 51%). Nine patients (12%) required plasmapheresis up to 30 days before starting venetoclax.

Treatment with venetoclax

The median time from diagnosis to starting venetoclax was 5.9 years (range, 0.1–22.3; missing n = 2). Venetoclax starting dose was 20 mg in 16 patients (22%), 50 mg in 3 (4%), 100 mg in 13 (17%), 200 mg in 37 patients (51%), and 400 mg in 4 (5.5%) (missing n = 3). Fifteen patients (21%) were admitted for venetoclax treatment initiation, and four were admitted more than once. The maximum venetoclax dose administered was 400 mg in 23 patients (32%) and 800 mg in 40 (56%) (other n = 7, missing n = 5). Twenty patients (26%) received venetoclax on a clinical trial. Patients treated with venetoclax on a clinical trial were less heavily pretreated (median prior lines of treatment = 1.5, 20% ≥3 prior treatments) and less likely to have received prior therapy with BTKi (n = 8/20, 40%) compared with those treated off trial (median prior lines of treatment = 4, 79% ≥3 prior, p = 0.005; n = 54/56 [96%] received prior BTKi, p = 0.001).

The median duration of treatment with venetoclax was 11.6 months (range, 0.5–50.0) (missing n = 20). Treatment with venetoclax was stopped due to PD in 27 patients (48%), planned treatment completion in 15 (27%) (all 15 received venetoclax for two years on a clinical trial), toxicity in 9 (16%), and other in 5 (9%). Twenty patients (26%) remained on venetoclax at the time of data cutoff, including nine patients who remained on venetoclax for more than two years. Overall, 12 patients received treatment with venetoclax for more than two years (21% (12/56) of patients treated off-trial).

Venetoclax dose interruptions and/or reductions occurred in 27 patients (41%) (interruptions n = 9 (14%), reductions n = 11 (17%), both n = 7 (11%), missing n = 10). Grade 3 and 4 neutropenia occurred in 15 (24%) and 13 patients (21%) (missing n = 14), respectively. The median time to nadir ANC was 1.9 months (range, 0.2–22.7). Four patients (5.5%) developed febrile neutropenia (missing n = 3). Five patients (7%) developed laboratory TLS (missing n = 2) (Table 3). Three patients (4%) met the criteria for clinical TLS, all based on the development of acute kidney injury (peak creatinine of 1.36–2.3 mg/dL). Laboratory TLS occurred at the venetoclax starting dose in 4 patients: 20 mg in one patient, 200 mg in two, and 400 mg in one (missing n = 1). Most patients (92%, missing n = 4) received prophylactic allopurinol, and 19 (27%, missing n = 5) received prophylactic intravenous fluids. Although limited by the small number of events, it is notable that patients who developed TLS had a high percentage of bone marrow involvement, splenomegaly, and/or lymph node enlargement but did not have high serum monoclonal protein levels, and most did not have CXCR4 or TP53 mutations. Further, TLS occurred at a wide range of venetoclax starting doses (20–400 mg).

Outcomes and prognostic factors

The ORR and major response rate to venetoclax in patients evaluable for response (n = 71, missing n = 5) were 70% and 63%, respectively: CR 3%, VGPR 20%, PR 41%, and MR 7%; 30% were refractory (SD 11% and PD 18%) (Fig. 1A). The median hemoglobin increased from 10.3 g/dL (range, 5.7–16.4) to 13.1 g/dL (range, 7.5–16.0), and the median serum IgM decreased from 2409 mg/dL (range, 5–9300) to 620 mg/dL (range, 0–4012). The median hemoglobin increased from 10.3 g/dL (range, 5.7–16.4) to 13.1 g/dL (range, 7.5–16.0), and the median serum IgM decreased from 2409 mg/dL (range, 5–9300) to 620 mg/dL (range, 0–4012). The median time from venetoclax start to best response was 3.8 months (range, 0.2–36.0) (missing n = 8), to peak Hb level was 4.6 months (range, 0.1–23.8) (missing n = 16), and to nadir serum M protein level was 6.9 months (range, 0.2–36.0) (missing n = 18). ORR was higher in patients treated on clinical trial (95% vs. 62%; odds ratio (OR) = 11.25; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.39–90.89; p = 0.023) and lower in patients who received ≥3 prior lines of therapy (61% vs. 86%; OR = 0.26; 95% CI, 0.08–0.87; p = 0.028) and in patients who received prior BTKi therapy (63% vs. 100%; p = 0.06) (Table 4, Fig. 1B–D). No factors were associated with ORR in multivariate logistic regression analysis. The major response rate was higher in patients treated on clinical trial (OR = 7.29; 95% CI, 1.53–34.79; p = 0.0128) and lower in patients who received ≥3 prior lines of therapy (OR = 0.23; 95% CI, 0.07–0.71; p = 0.0108) (supplementary table).

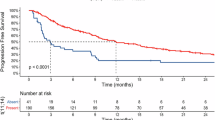

With a median follow-up of 19.3 months (range, 0.2–80.6), the median PFS and 2-year PFS rate were 28.5 months (95% CI, 11–32.5) and 57% (95% CI, 44–68), respectively (Fig. 2A). The median OS and 2-year OS rate were not reached (NR) (95% CI, NR-NR) and 82% (95% CI, 70%–90%), respectively (Fig. 2B). Lymphoma was the most common cause of death (n = 11/14, 79%). The 2-year PFS rate was higher in patients who received treatment with venetoclax on a clinical trial (85%; 95% CI, 60%–95%) than in patients treated off trial (43%; 95% CI, 27%–58%) (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.44; 95% CI, 0.22–0.89; p = 0.022; Table 5, Fig. 2C), and trended towards being higher in patients who received venetoclax 800 mg (66%; 95% CI, 49%–79%) vs 400 mg maximum dose (34%, 95% CI, 12%–57%) (HR = 0.56; 95% CI, 0.28–1.12; p = 0.0998; Fig. 2D). The 2-year PFS rate was lower in patients who received ≥3 prior therapies (42%; 95% CI, 26%–57%) than in patients who received 1–2 prior therapies (78%; 95% CI, 58%–90%) (HR = 2.07; 95% CI, 1.09–3.94; p = 0.027; Fig. 2E), in patients who received prior treatment with BTKi (47%; 95% CI, 33%–60%) than in patients who did not (92%; 95% CI, 57%–99%) (HR = 2.97; 95% CI, 1.28–6.90; p = 0.012; Fig. 2F), and in patients with TP53 mutations (38%; 95% CI, 8%–63%) than in patients without TP53 mutations (64%; 95% CI, 46%–78%) (HR = 2.62; 95% CI, 1.10–6.27; p = 0.035; Fig. 2G). The 2-year PFS rate was not different in patients with CXCR4 mutations (53%; 95% CI, 30%–72%) or without CXCR4 mutations (71%; 95% CI, 82%–84%) (HR = 1.47; 95% CI, 0.73–2.94; p = 0.28; Fig. 2H). Prior treatment with BTKi was the only factor associated with PFS in MVA (HR = 2.97; 95% CI, 1.28–6.90; p = 0.012). In a univariate analysis for OS, age >65 years at venetoclax treatment start (HR = 4.91; 95% CI, 1.09–22.17; p = 0.039) and receipt of ≥3 prior treatments (HR = 13.81; 95% CI, 1.76–108.31; p = 0.013) were associated with inferior OS whereas treatment with venetoclax on a clinical trial was associated with superior OS (HR = 0.05; 95% CI, 0.01–0.51; p = 0.011). In MVA, receipt of ≥3 prior treatments (HR = 10.19; 95% CI 1.31–79.18; p = 0.027) was the only factor associated with inferior OS.

A PFS and B OS in the overall patient population. PFS in patients treated with venetoclax on clinical trial vs. not (C), in patients treated with venetoclax 400 mg vs. 800 mg (D), in patients treated with 1-2 prior lines of treatment vs. ≥3 (E), in patients with prior treatment with BTKi vs. not (F), in patients with TP53 wild-type vs. mutant (G), and in patients with CXCR4 wild-type vs. mutant (H).

Discussion

Our study included heavily pretreated patients with a median of 3 prior lines of treatment, including BTKi and alkylating agents in most patients (82% and 71%, respectively). Further, treatment duration with covalent BTKi was short (median of 14 months), with most patients stopping BTKi due to PD. In this high-risk patient population, venetoclax resulted in high ORR (70%) and a prolonged PFS (median = 29 months, 2-year PFS rate = 57%). Responses to venetoclax were rapid, with median times to best response of 3.8 months and to peak Hb of 4.6 months. These data confirm the clinical activity of venetoclax in relapsed or refractory LPL/WM reported in the phase II trial by Castillo et al. [4]. Our study’s lower ORR and PFS (ORR = 84% and 2-year PFS rate = 80% in the phase II trial) likely reflect a more heavily pretreated cohort (median of 3 vs. 2 prior lines of treatment) and a higher proportion of patients receiving prior BTKi (82% vs. 50%). The impact of venetoclax dose (800 mg in the trial vs. 44% of patients receiving a lower dose in this study) on these outcomes is unclear as the optimal dosing of venetoclax in LPL/WM is not defined. Our data show a trend towards superior PFS in patients receiving venetoclax 800 mg vs. 400 mg maximum dose but without reaching statistical significance. The optimal treatment duration with venetoclax is also unclear. Venetoclax was administered for two years in the clinical trial by Castillo et al., with a rapid decline in PFS seen shortly after the second year, suggesting that prolonged treatment with venetoclax may be beneficial. This observation likely explains why treatment with venetoclax was not limited to two years in patients treated off-trial in our study.

Similar to the trial by Castillo et al. [4], our study showed inferior ORR and PFS in patients with ≥3 lines of prior treatment and no difference in ORR or PFS based on CXCR4 mutation status or IPSSWM score. However, in contrast to the trial, our data showed inferior ORR and PFS in patients with prior treatment with BTKi and no difference in ORR, major response rate, or PFS based on response to the most recent treatment before venetoclax. Further, our study showed inferior PFS in patients with TP53 mutations.

Venetoclax dose interruptions and reductions were common (40%) in our study. While we did not capture the cause of venetoclax dose interruptions or reductions, neutropenia was likely a significant contributor, as 45% of patients had grade ≥3 neutropenia while on treatment with venetoclax. However, the rate of febrile neutropenia was low. TLS occurred in five patients (7%), including clinical TLS in three (4%), despite implementing standard TLS mitigation strategies, such as dose ramp-up, prophylactic allopurinol, and inpatient monitoring. The small number of patients with TLS limits our ability to clearly define risk factors for TLS, but our limited data do not suggest that serum monoclonal protein levels or the presence of TP53 or CXCR4 mutations are associated with risk for TLS, whereas high disease burden in the bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes might be. Overall, TLS remains a rare but important complication of treatment with venetoclax in LPL/WM.

While chemoimmunotherapy and covalent BTKi are the preferred early lines of treatment for most patients with LPL/WM, the optimal sequencing of third and later lines of treatment is unclear. Proteasome-based regimens are commonly used; however, their efficacy in BTKi-treated patients is unknown [8,9,10,11,12]. Furthermore, the use of bortezomib and ixazomib is often limited by peripheral neuropathy and carfilzomib by cardiopulmonary complications [1, 8,9,10,11,12]. The noncovalent BTKi pirtobrutinib showed high efficacy (major response rate = 68%, median PFS = 22 months with a 22-month median follow-up) and excellent safety profile in heavily pretreated patients with LPL/WM, including those with prior treatment with covalent BTKi [13]. Our data support venetoclax as a preferred treatment option in multiply relapsed LPL, given its favorable efficacy and safety profiles. Venetoclax is also an attractive option for combination studies, particularly with BTKi, as preclinical evidence supports dual inhibition of BCL2 and BTK in LPL [2, 14]. Unfortunately, the combination of ibrutinib and venetoclax resulted in clinically significant ventricular arrhythmias in patients with WM, a phenomenon not seen with this combination in patients with other B-cell lymphoid malignancies [15]. However, venetoclax and other BCL2 inhibitors are being studied in combination with more selective and potentially safer covalent and noncovalent BTKi to improve efficacy and provide a time-limited treatment option in LPL/WM [16].

Our study has several limitations, including its retrospective nature, missing data, and heterogeneous treatment with venetoclax in terms of dose ramp-up schedule, target dose, and treatment duration. MVAs were limited by the relatively small sample size and missing data. Although we included patients treated with venetoclax on a clinical trial to increase the sample size, despite important differences between patients treated on vs. off trial, we adjusted for trial status and other known related factors in MVAs.

In conclusion, our multicenter retrospective study shows a high response rate and a prolonged PFS with venetoclax in patients with heavily pretreated LPL/WM and supports its use in this setting. However, the optimal dose and duration of treatment with venetoclax in LPL/WM remain unclear. TLS is an uncommon but important complication of treatment with venetoclax in LPL/WM.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Castillo JJ, Advani RH, Branagan AR, Buske C, Dimopoulos MA, D'Sa S, et al. Review consensus treatment recommendations from the tenth international workshop for Waldenström Macroglobulinaemia. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e827–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30224-6

Cao Y, Yang G, Hunter ZR, Liu X, Xu L, Chen J, et al. The BCL2 antagonist ABT-199 triggers apoptosis, and augments ibrutinib and idelalisib mediated cytotoxicity in CXCR4Wild-type and CXCR4WHIM mutated Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia cells. Br J Haematol. 2015;170:134–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.13278

Davids MS, Roberts AW, Seymour JF, Pagel JM, Kahl BS, Wierda WG, et al. Phase I first-in-human study of venetoclax in patients with relapsed or refractory Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:826–33. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.70.4320

Castillo JJ, Allan JN, Siddiqi T, Advani RH, Meid K, Leventoff C, et al. Venetoclax in previously treated waldenström macroglobulinemia. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:63–71. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.01194

Kumar SK, Callander NS, Adekola K, Anderson LD Jr, Baljevic M, Baz R, et al. Waldenström Macroglobulinemia/Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma, Version 2.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024;22:e240001. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2024.0001

Treon SP, Tedeschi A, San-Miguel J, Garcia-Sanz R, Anderson KC, Kimby E, et al. Report of consensus Panel 4 from the 11th International Workshop on Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia on diagnostic and response criteria. Semin Hematol. 2023;60:97–106. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminhematol.2023.03.009

Cairo MS, Bishop M. Tumour lysis syndrome: new therapeutic strategies and classification. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:3–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05094.x

Ghobrial IM, Xie W, Padmanabhan S, Badros A, Rourke M, Leduc R, et al. Phase II trial of weekly bortezomib in combination with rituximab in untreated patients with Waldenström Macroglobulinemia. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:670–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.21788

Castillo JJ, Meid K, Flynn CA, Chen J, Demos MG, Guerrera ML, et al. Ixazomib, dexamethasone, and rituximab in treatment-naive patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia: long-term follow-up. Blood Adv. 2020;4:3952–9. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001963

Chen CI, Kouroukis CT, White D, Voralia M, Stadtmauer E, Stewart AK, et al. Bortezomib is active in patients with untreated or relapsed Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia: a phase II study of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1570–5. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.07.8659

Treon SP, Hunter ZR, Matous J, Joyce RM, Mannion B, Advani R, et al. Multicenter clinical trial of bortezomib in relapsed/refractory Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: results of WMCTG trial 03-248. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3320–5. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2511

Treon SP, Tripsas CK, Meid K, Kanan S, Sheehy P, Chuma S, et al. Carfilzomib, rituximab, and dexamethasone (CaRD) treatment offers a neuropathy-sparing approach for treating Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2014;124:503–10. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-03-566273

Scarfò L, Patel MR, Eyre TA, Jurczak W, Lewis D, Gastinne T, et al. P1108: efficacy Of Pirtobrutinib, a highly selective, non-covalent (Reversible) Btk inhibitor in relapsed/Refractory Waldenström Macroglobulinemia: results from The Phase 1/2 Bruin Study. HemaSphere. 2023;7:e852670f. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HS9.0000971328.85267.0f

Paulus A, Akhtar S, Yousaf H, Manna A, Paulus SM, Bashir Y, et al. Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia cells devoid of BTK C481S or CXCR4 WHIM-like mutations acquire resistance to ibrutinib through upregulation of Bcl-2 and AKT resulting in vulnerability towards venetoclax or MK2206 treatment. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7:565. https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2017.40

Castillo JJ, Branagan AR, Sermer D, Flynn CA, Meid K, Little M, et al. Ibrutinib and venetoclax as primary therapy in symptomatic, treatment-naïve Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2024;143:582–91. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2023022420

Castillo JJ, Sarosiek SR, Branagan AR, von Keudell G, Flynn CA, Budano NS, et al. A phase II Study of pirtobrutinib and venetoclax in previously treated patients with waldenström macroglobulinemia: an interim analysis. Blood. 2024;144:3011. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2024-198297

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S. and J.J.C. conceived and designed the study, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; R.L.W performed statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript; S.S., S.S., S.T., S.Z., K.C., R.T., H.S., S.A., G.P., A.W., A.M., P.R., M.P., P.K., A.C., K.S., and S.T. collected and analyzed the data and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.G.C. reports honoraria from Janssen, Sanofi, Cellectar, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Pfizer. A.W. has consulted for BeiGene, BTG Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, and ADC Therapeutics. G.P. is a shareholder of Crispr Therapeutics and equity holder of Mevox Ltd and reports consultancy with ADC Therapeutics. J.J.C. received research funding from Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Beigene, Cellectar, Loxo, and Pharmacyclics, and consulting fees from Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Beigene, Cellectar, Janssen, Loxo, Mustang Bio, Nurix, and Pharmacyclics. K.H.S. reports honoraria from Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Adaptive, Sanofi, Regeneron, and Takeda, and research funding to the institution from AbbVie and Karyopharm, outside the submitted work. PAR reports serving as a consultant and/or advisory board member for AbbVie, Novartis, BMS, ADC Therapeutics, Kite/Gilead, Pfizer, CVS Caremark, Genmab, BeiGene, Janssen, Pharmacyclics, and Genentech/Roche. Honoraria from Adaptive Biotechnologies. Research support from BMS, Kite Pharma, Novartis, CRISPR Therapeutics, Calibr, Xencor, Fate Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Cellectis, Cargo Therapeutics, and Tessa Therapeutics. P.K. is the principal investigator of trials for which Mayo Clinic has received research funding from Amgen, Regeneron, Bristol Myers Squibb, Loxo Pharmaceuticals, Ichnos, Karyopharm, Sanofi, AbbVie and GlaxoSmithKline. Prashant Kapoor has received honorarium from Keosys and served on the Advisory Boards of BeiGene, Mustang Bio, Janssen, Pharmacyclics, X4 Pharmaceuticals, Kite Pharma, Oncopeptides, Ascentage, Angitia Bio, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi and AbbVie. SS received research funds or honoraria from Beigene, Cellectar, and ADC Therapeutics. ST received research funding from Ascentage Pharma, BMS, Genentech, Cellectar Biosciences, and Abbvie and has consulted for Cellectar Biosciences. YS received research funding from BeiGene, Genmab, and AbbVie and has consulted for ADC, Genmab, and Genentech.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sawalha, Y., Sarosiek, S., Welkie, R.L. et al. Outcomes of patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/waldenström macroglobulinemia treated with venetoclax: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Blood Cancer J. 15, 65 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01271-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01271-3