Abstract

Teclistamab, a BCMA-directed bispecific antibody, received regulatory approval for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) based on the MajesTEC-1 study. Despite the fact that myeloma is primarily a cancer of elderly adults, only 15% of MajesTEC-1 participants (n = 24) were ≥75 years old. In this multicenter retrospective study, we report real-world outcomes of a large cohort of older RRMM patients treated with teclistamab. Of 385 analyzed patients, 83 (22%) were in the older group (age ≥75) and 302 (78%) in the younger group (age <75). Compared to the younger group, the older group had less adverse baseline disease characteristics, including a lower incidence of high-risk cytogenetics (44.6% vs. 57.9%, p = 0.03) and extramedullary disease (22% vs. 40%, p = 0.02). There were no significant differences in rates of any-grade CRS (52% vs. 59%, p = 0.27), any-grade ICANS (19% vs. 13%, p = 0.12), and overall response rate (62% vs. 53%, p = 0.17) between the older and younger groups. In multivariable analysis, age was not significantly associated with survival outcomes. Our findings suggest that teclistamab is safe and efficacious in well-selected patients ≥75 years old, and advanced age alone should not preclude teclistamab administration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Teclistamab (Tec) is the first-in-class bispecific T-cell antibody approved for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) [1]. This approval was based on the results of the pivotal phase I-II MajesTEC-1 trial, which evaluated Tec, a dual targeting antibody that binds both CD3 and B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), in 165 patients with RRMM after at least three prior lines of therapy [2]. The overall response rate (ORR) was 63%, and the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 11.3 months. Median overall survival (OS), as reported after two years of follow-up, was 21.9 months [3]. The overall incidence of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) was 72.1% (n = 119, 0.6% grade 3/4) and of neurotoxicity 14.5% (n = 24, 0.6% grade 3/4).

The median age at diagnosis of MM is 69 years, and approximately one-third of patients are diagnosed at the age of 75 years or above [1]. Nonetheless, the elderly are underrepresented in clinical trials for MM. In the MajesTEC-1 study, only 15% of patients (n = 24) were aged ≥75 years at enrollment [2]. While underpowered to draw any definitive conclusions, the ORR was numerically lower in patients aged ≥75 (54%) than in younger patients (65%). In an analysis of 177 MM clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov between 2000 and 2016, 32% of enrolled participants were older than 65 years [4]. There has also been a downward trend in enrolling older patients over time, with only 23% of patients enrolled in clinical trials in 2016 being aged >65 years. Furthermore, despite the continuous development of novel drugs for patients with MM [5], the elderly have not experienced the same survival benefit as younger patients [6].

The addition of T-cell redirecting immunotherapy modalities, such as Tec, to the armamentarium against MM has put forth an opportunity and a challenge of incorporating these therapies in the management of older myeloma patients. Increased comorbidity burden and reduced organ reserves in this subgroup could have potential effects on the safety profile of Tec, especially in regards to CRS and ICANS [7].

There are limited data to date characterizing the safety and efficacy of Tec in older patients with MM [8, 9] to inform the feasibility of Tec administration in this patient population. Therefore, we conducted a multicenter retrospective study on behalf of the United States Multiple Myeloma Immunotherapy Consortium to evaluate the real-world safety and efficacy of a large cohort of elderly (≥75 years) RRMM patients treated with Tec.

Methods

Patient and data selection

We conducted a retrospective multicenter study of all consecutive patients with MM across 13 United States academic medical centers who participated in the United States Multiple Myeloma Immunotherapy Consortium. At each participating center, an Institutional Review Board approval for retrospective studies through the Consortium was obtained, including waiver of informed consent. Tec was administered according to the standard of care practice used at each center, including step-up dosing protocols, supportive care, and timing of response assessments. A secure REDCap interface [10] was used to collect relevant datapoints, with a margin of ±7 days for each data point. High-risk cytogenetic abnormalities (HRCA) were defined as deletion (del) 17p, translocation (t) (4;14), t(14;16), and/or gain or amplification of 1q21. Extramedullary disease (EMD) included both para-skeletal plasmacytomas and extramedullary soft tissue plasmacytomas [11]. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) assessment was based on the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy consensus grading [12]. International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) consensus criteria were used to assess response to Tec [13]. The follow-up data cutoff was 30 April 2024.

Statistical analyses

The cohort was divided into two age groups, patients aged ≥75 years (≥75 group) and those aged <75 years (<75 group), with the age cutoff of 75 chosen based on its previous use in the MajesTEC-1 trial of Tec. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics, disease characteristics, and clinical outcomes. The cutoff values to dichotomize the continuous variables, such as C-reactive protein and ferritin, were the upper quartile for each variable. The association between two categorical variables was evaluated using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Differences between patient groups in a continuous variable were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. A multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to estimate the effects of important variables on best overall response and survival outcomes. For time-to-event analyses, including PFS and OS, the Kaplan–Meier method was used, and the median time to event was calculated in months with a 95% confidence interval. Due to a significant imbalance of baseline patient characteristics in the two age cohorts, direct statistical comparisons in time-to-event end-points between the two age groups were not performed. Cox proportional hazards models were used for multivariable analysis. Schoenfeld residual was used to check the proportional hazards assumption. The baseline variables that had a p-value less than 0.05 for PFS or OS from the univariate analysis and without significant missing information were included in the full models. A backward selection method was used, and the final model included the covariates with a p-value less than 0.05.

Statistical software SAS 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC) and S-Plus 8.2 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA) were used for all the analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

Three hundred eighty-five patients were included in the analysis, and baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 83 (22%) were in the ≥75 age group (median age 78, range 75–92) and 302 (78%) in the <75 group (median age 65, range 31–74). Compared to patients in the <75 group, those in the ≥75 group were more often white (78% vs. 63%, p = 0.009). Both the ≥75 and <75 age groups had a median of 6 prior lines of therapy, and a similar proportion of patients had a performance status of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) ≥ 2 at the start of Tec (29% vs. 24%, respectively; p = 0.37). Both age groups had a high proportion of patients with triple-class-refractory disease (77% vs. 85%, p = 0.06) and patients who would have been ineligible for the MajesTEC-1 study (73% vs. 80%, p = 0.20). Patients in the ≥75 group had a lower incidence of some adverse MM risk features compared to the <75 group, including HRCA (44.6% vs. 57.9%, p = 0.03), ultra high-risk (≥2 HRCA) MM (12% vs. 24%, p = 0.02), EMD (22% vs. 40%, p = 0.02), hemoglobin <8 g/dL (10% vs. 21%, p = 0.02) and albumin <3 g/dL (6% vs. 19%, p = 0.04) at the time of starting Tec. Moreover, a lower number of pts in the ≥75 group had prior autologous stem cell transplantation (43% vs. 72%, p < 0.0001) or prior BCMA-directed therapy (33% vs. 55%, p = 0.0003). The median time from diagnosis of MM to start of Tec was longer for patients in the ≥75 group (7.21 years vs. 5.81 years, p = 0.02).

Safety

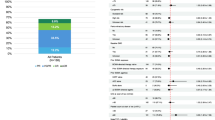

An accelerated step-up dosing schedule (defined as having at least one of the step-up dose intervals of less than three days apart) was used in 62% of the ≥75 group and 58% of the <75 group (p = 0.56). There were 12 patients (14%) in the ≥75 group and 33 (11%) in the <75 group (p = 0.35) who received outpatient step-up dosing. There was no significant difference in rates of any-grade CRS (52% vs. 59%, p = 0.27) or grade 2–4 CRS (10% vs. 11%, p = 0.74) between the ≥75 and <75 age groups, respectively. Four patients in the entire cohort developed CRS grade 3–4, one of whom was in the ≥75 group that developed grade 3 CRS (Fig. 1). Median time from start of Tec to onset of CRS and median time to maximal CRS were both 3 days, without a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.60 and p = 0.62, respectively). Twenty-six patients (31%) in the older age group received tocilizumab for CRS, compared to 121 (40%) in the younger age group (p = 0.54). Fourteen patients (17%) in the older age group received steroids for CRS, compared to 53 (18%) in the younger age group.

There was no significant difference between the two age groups in the rate of any-grade ICANS: 19% in the ≥75 group and 13% in the <75 group, p = 0.12. Ten patients developed grade 3 ICANS (none grade 4), three of whom were in the ≥75 group (Fig. 2). Median time from start of Tec to onset of ICANS was numerically shorter in the ≥75 group (3 days, range 0–25 days) compared to the <75 group (4 days, range 0–21 days), though not reaching a statistically significant difference (p = 0.89). Likewise, median time to maximal ICANS was numerically shorter in the ≥75 group (4 days, range 0–25 days) compared to the <75 group (5 days, range 0–22 days, p = 0.23). Moreover, the rate of a composite outcome of CRS grade 2–4 and/or any-grade ICANS was similar in both age groups (23% in the ≥75 group, and 21% in the <75 group).

A total of 20 patients in the ≥75 group and 118 patients in the <75 group died during follow-up. The most common cause of death in both age groups was progression of MM (70% of the total deaths in the ≥75 group and 75% in the <75 group), followed by infections (25% of the total deaths and 10%, respectively). The leading causes of infections leading to death in both age groups were sepsis and pneumonia (Supplementary Table 1). There was a trend toward lower rates of early death in the ≥75 group vs. the <75 group, when evaluating rates of death at 3 months (15% vs. 25%, respectively; p = 0.05) and at 6-months (22% vs. 31%, p = 0.1) after start of Tec.

Efficacy

There was no significant difference in ORR between the ≥75 group and the <75 group (62% vs. 53%, p = 0.17) and ≥very good partial response (VGPR) rate (53% vs. 44%, p = 0.14) (Fig. 3).

The median follow-up period was 8.7 months (95% CI 7.6–9.9 months) in the ≥75 group and 10.4 months (95% CI 9.9–11.2 months) in the <75 group. The unadjusted median PFS in the ≥75 group was 10.7 months (95% CI 6.6–NR) and was 5.2 months (95% CI 6.6–NR) in the <75 group (Fig. 4).

At the time of data cutoff, the median overall survival (OS) for patients in the ≥75 group had not been reached (95% CI NR–NR) and was 16.1 months (95% CI 14.0–NR) in the <75 group (Fig. 5). The OS rate at 12 months was 73% (95% CI 63%–84%) in the ≥75 group and 59% (95% CI 54%–66%) in the <75 group.

In multivariable analysis for the entire cohort, age ≥75 was not significantly associated with either PFS (HR 1.15, 95% CI 0.72–1.84; p = 0.55) or OS (HR 1.67, 95% CI 0.84–3.33; p = 0.15).

Factors that were associated with significantly worse PFS in multivariable analysis in the entire cohort included prior anti-BCMA targeting agent (HR 1.60, p = 0.0090), baseline ferritin ≥ upper quartile (HR 2.00, p = 0.0010), baseline CRP ≥ upper quartile (HR 1.61, p = 0.0146), baseline Hb <8 (HR 1.90, p = 0.0032) and presence of either plasma cell leukemia (HR 4.93, p = 0.0128) or EMD (HR 1.67, p = 0.0048) prior to start of Tec. Full details of multivariable analysis for PFS are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Factors that were associated with significantly worse OS in multivariable analysis in the entire cohort included ECOG ≥ 2 (HR 1.92, p = 0.0101), baseline CRP ≥ upper quartile (HR 2.58, p = 0.0002), baseline platelets <50 × 109/L (HR 2.54, p = 0.0005), baseline absolute lymphocyte count <0.5 × 109/L (HR 1.97, p = 0.0062) and presence of plasma cell leukemia prior to start of Tec (HR 5.24, p = 0.0320). Full details of multivariable analysis for OS are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

Discussion

We report a large multicenter study showing favorable outcomes for elderly RRMM patients ≥75 years of age treated with Tec in the real-world setting. We observed similar rates of overall and high-grade CRS or ICANS between the two age groups. The ORR was 62% in the ≥75 age group and 53% in the <75 group. The older group had an unadjusted median PFS of 10.7 months with a median OS not reached. The younger group had an unadjusted median PFS of 5.2 months and median OS of 16.1 months. Despite numerical differences in PFS and OS, age was not associated with survival outcomes in the multivariable analysis between the two age groups, likely reflecting patient selection and prescribing patterns in the early era of access to commercial anti-BCMA bispecific therapy with Tec, with more stringent selection patients in the older cohort who were fit with favorable disease characteristics.

The global population is gradually aging, and a report by the United Nations predicts that the number of people over the age of 80 will more than double its current number by the year 2050 [14]. The incidence of MM, a disease of the elderly, is also expected to increase almost twofold over the next quarter of a century [15], with MM patients living longer and requiring safe and efficacious treatment options. In this context, it is important that new anti-myeloma agents are evaluated in the older patient population. Previous research has shown that autologous stem cell transplantation can result in excellent outcomes in selected elderly MM patients aged ≥75 years [16]. A recent real-world study evaluated the safety and efficacy of idecabtagene vicleucel in older MM patients (aged ≥65 years) [17]. The ORR was 86.7% and 84.0% in the ≥65 group and <65 group, respectively (p = 0.92). There was numerically longer median PFS in the older cohort (9.1 months vs. 7.4 months), not reaching statistical significance (p = 0.39). The 12-month OS rates were 68% and 76.5% in the older and younger age groups, respectively. Coupled with the current report, it is encouraging that the emerging T-cell redirecting therapies are showing good tolerability and efficacy in older real-world cohorts. Moving forward, it is imperative that new treatment modalities be prospectively evaluated in a manner that reflects the real-world age distribution, with an emphasis on reducing barriers for elderly patients to enroll in clinical trials.

Response rates and survival outcomes in the elderly cohort of the current study were similar to the entire cohort reported on the MajesTEC-1 study [2]. The overall rate of CRS in our elderly cohort (52%) was lower than that reported in the MajesTEC-1 study (72.1%), and the ICANS rate was slightly higher (19% and 14.5%, respectively). Older patients often have lower organ reserves, including cardiac, pulmonary, and renal function [18], which may put them at higher risk for serious adverse events should CRS occur. However, it was encouraging to see that grade ≥3 events of CRS (n = 1) or ICANS (n = 3) were rare in the ≥75 age group. Importantly, these results were observed in a cohort of real-world RRMM patients, with most patients (73% in the older cohort) who would have been ineligible for MajesTEC-1.

A previous retrospective analysis by Dima et al., which was presented in abstract form, evaluated the outcomes of 33 patients aged >70 years old who received Tec in 5 US academic centers [9]. Overall patient characteristics were similar between the older and younger groups in that report, besides ECOG of ≥2, which was more prevalent in the >70 age group. This is in contrast to the current study, where we observed a lower incidence of adverse MM risk factors in the older age group, including HRCA and extramedullary disease, and a lower proportion of older patients in our cohort had received prior autologous stem cell transplantation or prior BCMA-directed therapy. Furthermore, in the current study, there was no difference in the performance status between the two age groups. The discrepancy between the two studies in baseline characteristics may be partially explained by the higher patient number in the current study, allowing for better elucidation of differences between the age groups. Nonetheless, similar to our study, the analysis by Dima et al. also did not observe significant differences between the two age groups in major efficacy and safety outcomes, including ORR (p = 0.37), median PFS (p = 0.61), CRS rates (p = 0.7) and ICANS rates (p = 0.17).

Our study has several inherent limitations, due to its retrospective and multicenter nature, including selection bias, variability in care, leading to inconsistencies in treatment and outcomes, and confounders that were unaccounted for despite the use of multivariable Cox regression analysis. Being a retrospective study, it is possible that several patients were inadvertently left out of this analysis, and data may have been incomplete and/or unavailable in some cases, affecting the reliability of the findings. However, each participating center was asked to submit all consecutive patients treated with teclistamab at their center for this analysis and other analyses for the U.S. Multiple Myeloma Immunotherapy Consortium. Moreover, a querying process to each center was utilized to address any inconsistent and/or missing data during the analysis. Due to unbalanced baseline patient and disease characteristics between the two age groups as described earlier, we were unable to make direct comparisons in survival outcomes. We also did not have access to frailty scores, which may be a more important determinant of outcomes in older patients than chronological age alone [19].

In conclusion, in this large, real-world multicenter study, we observed favorable safety and efficacy outcomes in elderly RRMM patients who received Tec. Rates of CRS and ICANS, as well as ORR and PFS, were comparable to those seen in the younger age group, as well as those seen in the pivotal MajesTEC-1 clinical trial. Our results suggest that Tec can be safely administered also in select patients aged ≥75 years old, and advanced age should not be the sole reason to preclude treatment. Instead, careful patient selection, based on functional status and comorbidities [20], should be employed to expand access to this important anti-myeloma modality.

Data availability

The underlying data of this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

National Cancer Institute. Surveillance E, and End Results (SEER) Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Myeloma 2022. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html.

Moreau P, Garfall AL, van de Donk N, Nahi H, San-Miguel JF, Oriol A, et al. Teclistamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:495–505.

Donk, NWCJvd, Moreau P, Garfall AL, Bhutani M, Oriol A, Nooka AK, et al. Long-term follow-up from MajesTEC-1 of teclistamab, a B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) x CD3 bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:8011

Duma N, Azam T, Riaz IB, Gonzalez-Velez M, Ailawadhi S, Go R. Representation of minorities and elderly patients in multiple myeloma clinical trials. Oncologist. 2018;23:1076–8.

Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2024;99:1802–24.

Jones A, Bowcock S, Rachet B. Survival trends in elderly myeloma patients. Eur J Haematol. 2021;106:126–31.

Martin TG, Mateos MV, Nooka A, Banerjee A, Kobos R, Pei L, et al. Detailed overview of incidence and management of cytokine release syndrome observed with teclistamab in the MajesTEC-1 study of patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Cancer. 2023;129:2035–46.

Dieterle MP, Mostufi-Zadeh-Haghighi G, Kus JW, Wippel C, Brugger Z, Miething C, et al. Safe and successful teclistamab treatment in very elderly multiple myeloma (MM) patients: a case report and experience from a total of three octogenarians. Ann Hematol. 2023;102:3639–41.

Dima D, Sannareddy A, Ahmed N, Davis JA, Shaikh H, Mahmoudjafari Z, et al. Toxicity and efficacy outcomes of teclistamab in patients with relapsed-refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) above the age of 70 years: a multicenter study. Blood. 2023;142:3330.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42:377–81.

Zanwar S, Sidana S, Shune L, Puglianini OC, Pasvolsky O, Gonzalez R, et al. Impact of extramedullary multiple myeloma on outcomes with idecabtagene vicleucel. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17:42.

Lee DW, Santomasso BD, Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Turtle CJ, Brudno JN, et al. ASTCT consensus grading for cytokine release syndrome and neurologic toxicity associated with immune effector cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2019;25:625–38.

Kumar S, Paiva B, Anderson KC, Durie B, Landgren O, Moreau P, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e328–46.

Division UP. World population ageing 1950-2050 2002. Available from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/ https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2021/Nov/undesa_pd_2002_wpa_1950-2050_web.pdf.

Weir HK, Thompson TD, Stewart SL, White MC. Cancer incidence projections in the United States between 2015 and 2050. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E59.

Munshi PN, Vesole DH, St Martin A, Davila O, Kumar S, Qazilbash M, et al. Outcomes of upfront autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma who are 75 years old or older. Cancer. 2021;127:4233–9.

Kalariya NM, Hildebrandt MAT, Hansen DK, Sidana S, Khouri J, Ferreri CJ, et al. Clinical outcomes after idecabtagene vicleucel in older patients with multiple myeloma: a multicenter real-world experience. Blood Adv. 2024;8:4679–88.

Zhang H, Cherian R, Jin K. Systemic milieu and age-related deterioration. Geroscience. 2019;41:275–84.

Mian H, McCurdy A, Giri S, Grant S, Rochwerg B, Winks E, et al. The prevalence and outcomes of frail older adults in clinical trials in multiple myeloma: a systematic review. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13:6.

Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Mateos MV, Larocca A, Facon T, Kumar SK, et al. Geriatric assessment predicts survival and toxicities in elderly myeloma patients: an International Myeloma Working Group report. Blood. 2015;125:2068–74.

Funding

LF acknowledges support by the Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG), grant number: NCI Grant P30 CA016672. ALG acknowledges support from a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Scholar in Clinical Research Award. DKH acknowledges support by the NCI (R01CA281756-01A1) and the Pentecost Family Myeloma Research Center. HCL acknowledges funding from the Baer Family Fund and the Goff-Street Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OP and HCL conceived and designed this study. OP, LF, WD, and HCL analyzed the data. OP, DD, KKP, HCL, and AGC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. OP, DD, LF, WD, TR, JAD, AA, MV, AS, UG, RB, JK, FC, MRG, AL, MSR, KJ, CJF, LS, SD, EB, SSA, AP, HH, LM, GK, AR, MMH, DS, CL, SR, YL, SM, DN, SA, JM, DS, PV, FA, MA, CF, ALG, BMR, SS, AJC, LDAJ, DKH, SR, KKP, HCL and AG contributed patients to this analysis, provided critical feedback, and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JAD reports consulting: Janssen; speakers’ bureau: Janssen. AA reports research funding from AbbVie, Adaptive Biotech, K36-therapeutics, J&J, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; advisory role for Karyopharm, BMC, Sanofi, J&J, Pfizer. RB reports consulting: Adaptive Biotech, BMS, Caribou Biosciences, Genentech, Janssen, Karyopharm, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, Sanofi, SparkCures; Research: AbbVie, BMS, Janssen, Novartis, Pack Health, Prothena, Sanofi. JK reports consulting: GPCR, Janssen, Prothena, Legend Biotech; research: Prothena, Ascentage, Janssen, Karyopharm, GPCR. MRG reports consulting or advisory role - Bristol Myers Squibb and Arcellx. KJ reports being an advisory board consultant for Janssen, Pfizer, and BioLineRx. LS reports consulting: BMS. SSA reports consulting: Sanofi. HH reports consulting: Janssen; speaker bureaus: Janssen, Karyopharm. LM reports advisory board with legend and bioline Rx. GK reports consulting: BMS, Arcellx, Sanofi, Janssen, Cellectar, Pfizer, Kedrion; Research: BMS, Janssen, AbbVie. YL reports consulting: Janssen, Legend, Celgene, Sanofi, BMS, Pfizer, Regeneron, Genentech, NexImmune, Caribou; research funding: Janssen, Celgene, BMS. JM reports consulting: Envision, Novartis, Caribou Bio, Sana Technologies, Legend Biotech, Cargo Therapeutics. Ad Board: Autolus. Consulting/Ad board: Kite/scimentum, Allovir, BMS, CRISPR, Nektar. DS reports consulting for BMS, GSK, Sanofi, Janssen, Opna Bio, Genentech, Pfizer, and AbbVie. FA reports serving as advisor and speaker for Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Caribou Biosciences; received research funding from Allogene Therapeutics, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Caribou Biosciences. ALG reports research funding from Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, CRISPR Therapeutics, and Tmunity Therapeutics; consultant relationships with Gracell, Johnson & Johnson, Smart Immune, AbbVie, Regeneron, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Novartis; Independent Data Monitoring Committee service for Johnson & Johnson. SS reports research: Magenta Therapeutics, BMS, Allogene, Janssen, Novartis, AbbVie; Advisory Board/Consultancy: BMS, Janssen, Sanofi, Oncopeptides, Takeda, Regeneron, AbbVie, Pfizer, BiolineRx, Legend, Kite. AJC reports research funding: Janssen, BMS, Juno/Celgene, Sanofi, Regeneron, IGM BIosciences, Nektar, Harpoon, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Caelum, AbbVie, OpnaBio, Karyopharm, Advisory/Consulting: Sebia, Janssen, BMS, Sanofi, HopeAI, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Pfizer. LDA reports consulting: Janssen, Celgene, BMS, Amgen, GSK, AbbVie, BeiGene, Cellectar, Sanofi, Prothena. Research: BMS, Celgene, GSK, Janssen, AbbVie. DKH reports research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Karyopharm, Kite Pharma, and Adaptive Biotech; Consulting or advisory role for Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, Kite Pharma, AstraZeneca, and Karyopharm. ShRi reports honoraria: Janssen, BMS, Genentech, Karyopharm Therapeutics, MJH LifeSciences; steering committees: Gracell Therapeutics, BMS; research support: Janssen, BMS, C4 Therapeutics, Gracell Therapeutics, Heidelberg Pharma; consulting: Genentech, Janssen, BMS, Karyopharm Therapeutics. KKP reports consulting: BMS, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Legend Biotech, Kite, Genentech, AbbVie, Sanofi, Caribou, Takeda, Regeneron, Poseida. HCL reports consulting: Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Janssen, Regeneron, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, AbbVie, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Allogene Therapeutics, Menarini, Alexion Pharmaceuticals; research funding: Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, GSK, Regeneron, Takeda Pharmaceuticals. AGC reports Janssen: speaker bureau, advisory board, research funding; Sanofi: advisory board, speaker bureau; BMS: advisory board; Pfizer: advisory board, speaker bureau; Cellectar: advisory board; Amgen: speaker bureau. The remaining authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients included in this analysis have provided informed consent for participation in the study. The study was conducted in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) and Good Clinical Practices (GCPs). The protocol was approved by the respective Institutional Review Board or ethics committee at each of the participating institutions (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA; Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH; Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC; Myeloma, Waldenstrom’s, and Amyloidosis Program, Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX; Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL; Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY; Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA; Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT; Atrium Health Levine Cancer Institute, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Charlotte, NC; University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS; Abramson Cancer Center and Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA; Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, NY; Duke University Cancer Institute, Durham, NC; Mayo Clinic, Division of Hematology, Rochester, MN; Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA; all in the USA). All subjects provided documented informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All authors had access to the data and contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results. The authors confirm the accuracy and completeness of the data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pasvolsky, O., Dima, D., Feng, L. et al. Outcomes of elderly patients with relapsed refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) treated with teclistamab: a multicenter study from the U.S. Multiple Myeloma Immunotherapy Consortium. Blood Cancer J. 15, 92 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01297-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01297-7

This article is cited by

-

Antibody-Drug Conjugates, T-Cell Engager Bispecific Antibodies and Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells for Multiple Myeloma: What’s the Current Status?

Targeted Oncology (2026)

-

Complete Response to Teclistamab in a Pentarefractory Elderly Patient with Multiple Myeloma: A Real-World Case Report from India

Indian Journal of Hematology and Blood Transfusion (2025)