Abstract

Bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) have shown promise in the management of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM). Despite its efficacy, this class of drugs is associated with significant toxicities. In this study, we conducted a pooled analysis of the available clinical trials on BsAbs for the treatment of MM, including full publications and abstracts until April 2025. BsAbs were classified into two groups: B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), and GPRC5D/FcRH5 BsAbs. Welch’s t-test was performed to compare the safety profiles of each agent. For clustering, we used principal component analysis (PCA). Our study analyzed 22 trials involving 2374 patients with MM from early 2023 to April 2025. Among these, 1276 patients received BCMA BsAbs, 841 treated with GPRC5D/FcRH5 BsAbs, 157 received teclistamab + talquetamab, and 65 patients received a talquetamab + daratumumab, and 35 patients received talquetamab + pomalidomide. The median follow-up for all groups was 11.83 months. Among all-grade hematologic adverse events (AEs), neutropenia occurred in 40.4%, anemia in 39.2%, thrombocytopenia in 21.4%, lymphopenia in 19.2%, infections in 45.8%, and cytokine release syndrome (CRS) in 65%. For grade 3/4 AEs, infections occurred in 20.3%, CRS in 1.5%, neutropenia in 35.2%, anemia in 24.5%%, thrombocytopenia in 13.5%, and lymphopenia in 17.7%. CRS and the need for tocilizumab were significantly less frequent with BCMA BsAbs vs GPRC5D/FcRH5 BsAbs, (P < 0.002). Skillings Mack (Generalized Friedman’s) findings emphasized substantial distinctions between BCMA and GPRC5D/FcRH5×CD3 in both overall and severe grade 3/4 AEs (p ≤ 0.0002). PCA revealed agents with all grades and grade 3/4 showed similar clustering patterns except for three agents. Overall, our findings demonstrated the excellent efficacy on the use of BsAbs in MM; however, these agents have been linked to a unique AE profile. GPRC5D/FcRH5 are associated with less grade 3/4 hematologic toxicity whereas BCMA BsAbs were associated with lower grade 3/4 CRS rates, compared to GPRC5D/FcRH5. These insights are crucial for guiding treatment decisions and developing strategies to improve patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most prevalent hematologic malignancy, with recent advancements in patient outcomes largely attributed to new therapeutic options [1]. Over the past 25 years, the use of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to amplify the immune system’s capacity to fight tumors has gained significant momentum, sparking a surge of further research in this field. BsAbs are bio-engineered antibodies designed to simultaneously bind two different antigens: a tumor-specific antigen (such as BCMA) and a T-cell receptor (CD3). This interaction results in an immunological synapse, leading to T cell degranulation and destruction of target cells via perforin and granzyme B, while also promoting T cell activation and memory cell differentiation [2, 3] BsAbs are increasingly being used in penta-refractory MM resistant to two proteasome inhibitors, two immunomodulatory drugs, and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody [4].

Generally, BsAbs used in MM treatment are classified into two major categories: “B-cell Maturation Antigen” (BCMA) and G protein-coupled receptor class C group 5 member D (GPRC5D) or Fc receptor-homolog 5 (FcRH5) targeting BsAbs. The former target BCMA or CD269, also known as tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 17 (TNFRSF-17), which is highly expressed in malignant plasma cells; and CD3 on T cells, triggering its activation and subsequent destruction of the cancer cells [5]. These include FDA-approved agents teclistamab and elranatamab, as well as several other investigational agents. GPRC5D/FcRH5 targeting Bispecific-Abs include agents targeting GPRC5D such as talquetamab and FcRH5 such as cevostamab which targets f on myeloma cells and CD3 on T cells and agents targeting FcRH5 on myeloma cells and CD3 on T cells. These novel targets provide an alternative for patients who have developed resistance to BCMA-targeted therapies and vice versa, allowing the immune system to attack myeloma cells via a different antigen [6].

These advancements in MM treatment have shown significant and encouraging outcomes. However, the use of BsAbs is associated with adverse events (AEs). Several potential molecular mechanisms have been proposed to explain the complex interplay between AE occurrence and the type of BsAbs used, genetic predispositions, and geographic location of patients [7]. Additionally, discrepancies in AEs observed in MM patients may result from the usage of different combination regimens and dosing, underlying co-morbidities, age, and gender [8,9,10]. Several ongoing clinical trials are elucidating the influence of these and other risk factors on the toxicity profile of BsAbs with particular attention to CRS, pancytopenia, skin rash, gastrointestinal toxicity, and infection rates. This study aims to quantitatively assess and provide a comprehensive characterization of the reported adverse events and toxicities associated with bispecific BsAbs therapies in the management of MM.

Methods

Data curation

AEs

As defined by the FDA [11], the term AE refers to any unfavorable or unintended sign (including an abnormal laboratory finding), symptom, or disease caused using a medical treatment or procedure. In medical documentation and scientific analyses, AEs are unique representations of a specific event.

Database sources

To systematically organize various databases containing information on patients with relapsed refractory MM from June 2022 to April 2025, we extracted data from two studies in PubMed, one study in Nature, one study in the Lancet, four studies in Blood, seven studies in the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), three studies in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), and four studies in the American Society of Hematology (ASH), focusing on BCMA and GPRC5D/FcRH5 Bispecific Abs. Additionally, we refined our dataset by manually searching published articles and abstracts for common AEs. Our analysis of BCMA agents included information from the following sources: Data from referenced sources for teclistamab (Tec) [12,13,14,15,16], elranatamab (Elr) [17], F182112 (F) [18], linvoseltamab (Linvo) or REGENERON-5458 (R5458) [19,20,21,22], AMG420 (AMG4) [23], AMG720 (AMG7) [24], alnuctamab (Aln) or CC-93269 (CC) [25], and ABBV-383 (ABBV) [26]. For non-BCMA GPRC5D agents, our analysis encompassed studies involving talquetamab (Tal) [27,28,29], and results of MonumenTAL-1 for Tal [30], and non-BCMA FcRH5 includes cevostamab (Cevo) [31]. Additionally, data were obtained from studies combining two different types of agents such as Tec + Tal (BCMA×GPRC5D) [32, 33], Tal + daratumumab (Tal + Dara) [34], and Tal + pomalidomide (Tal + Pom) [35]. In this study, certain agents administered in combination with Tal were excluded due to their complex profiles; nonetheless, two of these agents were retained for inclusion in the analysis.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was not required for this study as it was conducted using publicly available data from previously published clinical trials and abstracts. No new patient-level data was collected or analyzed, and all information used in this study was already available in public domain databases.

Statistical analysis

In this research, we employed a set of statistical tests, including both parametric and non-parametric approaches, to determine their comparative efficacy. The parametric tests included Welch’s t-test provided by (Eq. (3)) below, while non-parametric tests comprised the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and generalized Friedman test called Skilling Mack test [36].

Addressing missing/nonreported events

Since the data originated from different populations for different agents, it was necessary to standardize them to ensure comparability on a uniform scale. This process involved normalizing each agent by its total population to scale the values ranging within a similar interval, in this case between 0 and 1. To address this, after the normalization process, it was required to find an optimal approach for imputation. Various imputation methods, including filling with values such as minimum, half, maximum, 0, 1, or mean, or values drawn from mean ± standard deviation, or mean ± standard error of the mean, were examined. By employing box plots for visualization, we found the most reliable imputation strategy for our purpose. Ultimately, we applied the Skillings-Mack test to manage missing values in the dataset, which operates on incomplete AEs block designs by ranking available observations within each block. This allowed us to generate a rank-based matrix, where each observation was ranked relative to others within the same AE block, without the need to impute missing values directly. We used rank data for our clustering.

Analysis of AEs safety through pooling of data

We conducted Welch’s t-test to calculate p-values (\(\alpha\)<0.05) for comparisons between different classes of AEs including hematologic, non-hematologic and all AEs. For this purpose, a pooled analysis was conducted to obtain pooled mean Eq. (1) and pooled variance Eq. (2) values, facilitating the calculation of standard deviation: The following formulas were used to calculate the pooled mean:

and pooled variance:

where \({n}_{ij,l}\) is the total number of agents involved with \(A{E}_{ij,l}\), for \(i\in \left\{\mathrm{1,2},\ldots ,m\right\}\), each separate adverse event \(j\in \{\mathrm{1,2},\ldots k\}\), for \(l\in \{\mathrm{1,2}\}\), corresponding to BCMA and GPRC5D/FCRH5 BsAbs, respectively. Welch’s t-test is a suitable method for handling data with different sample sizes. The result of Eq. (2) was applied in the computation of Welch’s t-test. Welch’s t-test was conducted on hematologic AEs for all grades within BCMA agents and GPRC5D/FCRH5 agents. This involved performing Welch’s t-test with pooled mean and pooled standard deviation. The same procedure was repeated for non-hematologic AEs for all grades within BCMA agents and GPRC5D/FCRH5 agents. The process was replicated to compute Welch’s t-test for grade 3 or higher AEs.

where \({N}_{i,l}={n}_{i1,l}+{n}_{i2,l}+\ldots +{n}_{ij,l}+\ldots +{n}_{ik,l}.\)

To identify differences across all agents, or within each group of BCMA and GPRC5D/FCRH5 agents, we utilized the pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank test. We implemented the Holm p-value adjustment to correct for multiple comparisons. Furthermore, we performed the Wilcoxon test separately for the entire set of BCMA agents and GPRC5D/FCRH5 agents, considering all grade AEs or grade 3/4 AEs, hematologic and non-hematologic AEs, or hematologic AEs only. We then employed the Skillings–Mack statistic [36], which is a generalization of the Friedman test and is suitable for a broad range of block designs, including those with arbitrary missing/not reported data patterns. This test was used to compare differences between the groups of agents. Initially, we applied for this test individually to BCMA agents and GPRC5D/FCRH5 agents. Then, we combined the groups of BCMA and GPRC5D/FCRH5 agents to perform the Skillings–Mack test. This analysis was conducted for both all-grade AEs and grade 3/4 AEs as well as hematologic and non-hematologic AEs, or hematologic AEs only. The Skillings–Mack test, performed in R (version 4.5.2), yielded p-values (<0.05) for these comparisons, suggesting statistical significance.

Clustering: principal component analysis (PCA)

Our dataset consisted of over one hundred dimensions which made it challenging to analyze and identify common data characteristics. To address this complexity, we applied PCA [37,38,39], as a linear dimension reduction and clustering technique to represent our data in two dimensions, facilitating easier visualization and analysis. In this process, we used PCA on our dataset after normalization and filling out missing values. To manage missing values in the dataset, we applied the Skillings-Mack test to generate a rank-based matrix. To enhance the contrast among ranked values, we normalized the rank matrix by multiplying each entry by 10 and then raising it to the power of 6. The PCA strength lies in effectively projecting high-dimensional data onto lower-dimensional spaces while preserving crucial underlying structures. The initial phase of the algorithm depends on performing an eigen decomposition of the covariance matrix to identify directions of maximum variance, known as principal components. By projecting the data onto the top 2 principal components, PCA preserves the global structure and most significant variance patterns while discarding less informative, noise-dominated dimensions.

Results

Patients characteristics

This analysis included 2374 patients with MM who participated in 22 separate trials. A total of 1276 patients were treated with anti-BCMA agents including Tec, TecU1, TecU2, TecJPh1, TecJPh2, Tecout, Elr, ElrP1, ElrP2B, F, Linvo, R5458U2, R5458U3, AMG4, AMG7, CC, Aln, ABBVSD, ABBVID, ABBVLD, ABBV and RE5458 (abbreviations defined in Supplementary Materials 1) compared to 841 patients treated with GPRC5D/FCRH5 agents including Tal405U2, Tal800U2, TalSC, TalIV, Tal_0.4, Tal_0.8, Tal_TCR, and Cevo (abbreviations defined in Supplementary Materials 1). Additionally, 157 patients received both BCMA with GPRC5D Bispecific ABs, while 65 patients received GPRC5D anti-agent Tal and CD38 targeting Dara. Also, 65 patients were treated with a combination of Tal + Dara and 35 patients with Tal + Pom. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics baseline for MM patients reported in 22 different selected studies including phase of studies and prior specific treatments with time of diagnosis for each patient, for the complete datasets, see tables in Supplementary Materials 2. The median age of the included patients was 65.5 years, with the following averages for each group: BCMA (66), GPRC5D/FCRH5 (64.8), BCMA × GPRC5D (65.5), and Tal + Dara/Pom (64). Most patients were male (45.32%). The racial composition was predominantly White (53.54%).

Baseline characteristics

At baseline, most patients had an ECOG performance status of ≥1 (38.16%), with 20.77% having an ECOG performance of 0. High-risk cytogenetics were present in 21.36%. The presence of extramedullary disease (EMD) was noted in 15.54% of patients. Previous exposure to Penta-drugs was seen in 58.72%, while 72.33% had prior Triple-class exposure. The refractoriness rates were high, with 73.84% being refractory to Triple-class, 50.72% to monoclonal antibodies, and 39.60% to IMiDs. Refractoriness to the last line of therapy was reported in 66.76%. BCMA-targeting agents were predominantly used in patients with a median of 5.1 prior lines of therapy (range: 4–7). GPRC5D/FcRH5 agents: Median 5.5 prior lines (range: 4.5–6). BCMA + GPRC5D/FcRH5: Median 4-5 prior lines. Tal + Dara/Pom: Median 3–5 prior lines, suggesting use in less refractory populations.

Efficacy

Table 2 describes the efficacy reported for different responses to each agent for MM patients for selected studies, for the complete datasets, see tables in Supplementary Materials 2. Median follow-up for all groups was 11.83 months. The median time since diagnosis for all groups was 6.26 years. The median number of prior lines of therapy (PLOT) for both groups of patients was 5.17. The overall response rate (ORR) was 60.57%, with the highest ORR observed in the Tal + Dara/Pom group (81%). Complete response (CR) or stringent complete response (sCR) occurred in 6.99%, with Tal + Dara/Pom showing the highest rate (19.62%). Very good partial response (VGPR) was 17.02%, with Tal + Dara/Pom showing the highest VGPR at 25%. Partial response (PR) was seen in 7.96%, with GPRC5D/FCRH5 having the highest PR rate (9.51%). The median time to response was 1.21 months and the median time to best response was 4.03 months.

Safety

Table 3 describes adverse events (safety profiles) including hematologic and non-hematologic, reported for each agent in 22 studies. The safety analysis is summarized below:

-

AEs: All-grade AEs occurred in 67.73%, with the highest incidence in the Tal + Dara/Pom group (100%), followed by BCMA (74.37%), BCMA×GPRC5D and (59.87%), GPRC5D/FcRH5 (55.29%). Grade 3/4 AEs were most frequent in the Tal + Dara/Pom group (82%), followed by BCMA×GPRC5D (57.32%), BCMA (57.05%), and GPRC5D/FcRH5 (43.04%).

-

Hematologic AEs

All-grade hematologic AEs

-

○

Neutropenia: Highest in BCMA×GPRC5D (74.52%) vs. BCMA (37.7%), GPRC5D/FcRH5 (37.34%), and Tal + Dara/Pom (46%).

-

○

Anemia: Most frequent in BCMA × GPRC5D (57.96%) and GPRC5D/FcRH5 (44.95%), compared to BCMA (32.76%) and Tal + Dara/Pom (43%).

-

○

Lymphopenia: Predominated in GPRC5D/FcRH5 (26.75%), with BCMA (18.1%); absent in BCMA×GPRC5D and Tal + Dara/Pom.

Grade 3/4 hematologic AEs

-

○

Neutropenia: Highest in BCMA × GPRC5D (70.7%) vs. BCMA (33.86%), GPRC5D/FcRH5 (30.68%), and Tal + Dara/Pom (34%).

-

○

Anemia: Most severe in BCMA×GPRC5D (40.13%) and GPRC5D/FcRH5 (27.35%), versus BCMA (21.94%) and Tal + Dara/Pom (9%).

-

○

-

Non-Hematologic AEs

CRS and ICANS.

-

○

Anemia: Most severe in BCMA × GPRC5D (40.13%) and GPRC5D/FcRH5 (27.35%), versus BCMA (21.94%) and Tal + Dara/Pom (9%).

-

○

CRS: Highest in Tal + Dara/Pom (77%) and BCMA×GPRC5D (79.62%), compared to BCMA (56.82%) and GPRC5D/FcRH5 (73.13%).

-

○

ICANS: More frequent with GPRC5D/FcRH5 (7.02%) vs. BCMA (2.04%), BCMA × GPRC5D (2.55%), and Tal + Dara/Pom (5%).

Infections and other AEs

-

○

Infections (all-grade): Most common in Tal + Dara/Pom (66%), followed by BCMA × GPRC5D (53.5%), BCMA (45.3%), and GPRC5D/FcRH5 (42.57%).

-

○

Infections (Grade 3/4): Highest in BCMA×GPRC5D (38.22%) vs. BCMA (21.63%), GPRC5D/FcRH5 (14.51%), and Tal + Dara/Pom (24%).

-

○

Hypogammaglobulinemia: Prominent in BCMA (14.58%) and Tal + Dara/Pom (55%), but rare in GPRC5D/FcRH5 (4.88%).

-

○

Other AEs:

-

○

Diarrhea: Comparable between BCMA (23.59%) and GPRC5D/FcRH5 (24.97%); absent in Tal + Dara/Pom.

-

○

Fatigue: Highest in GPRC5D/FcRH5 (26.52%) and Tal + Dara/Pom (29%) vs. BCMA (24.76%).

-

○

-

Fatal AEs: 12.55% overall, primarily attributed to progressive disease (3.58%) or treatment-related AEs (3.88%), with higher AE-related mortality in the BCMA group Full datasets can be found in Supplementary Materials.

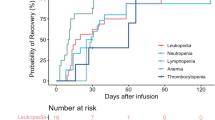

Statistical results

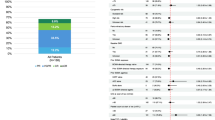

Using the pooled analysis, we found that the highest reported grade 3/4 AEs were neutropenia (35.17%), infections (26%), anemia (24.52%), thrombocytopenia (21.44%), lymphopenia (17.73%), leukopenia (5%), and hypogammaglobulinemia (18%). All grade AEs together BCMA and non BCMA are described in Supplementary Materials 2. The Skillings–Mack test results for comparing BCMA, GPRC5D/FcRH5, and all agents together for all grades were obtained as follows: \(P \,=\, 0.0003\), \(P=0.0206\), and \(P\ll 0.0001\), respectively. Conducting the test for grade 3/4, we obtained the following p-value results: 0.1061, 0.551, and 0.0002. The same analysis was also performed for hematologic and non-hematologic AEs, as well as hematologic AEs alone. Complete results are provided in Supplementary Materials 1. Employing the Wilcoxon test for pairwise comparisons within each group of agents involved several steps. Initially, we applied the Wilcoxon test independently to assess the statistical significance of differences across all agents, BCMA, and GPRC5D/FcRH5 groups (Fig. 1) across all grades, no significant results were observed. We then conducted the same Wilcoxon tests for grade 3/4 (Fig. 2), yielding no statistical significance. Other comparisons are provided in Supplementary Materials 1.

Top panel presents boxplots for all agents, bottom left panel for BCMA agents, and bottom right panel for GPRC5D/FcRH5 agents, with Chi-square statistics, p-values, and degrees of freedom shown on top of each panel. No statistically significant p-values were observed in the pairwise agent’s comparison with Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

Top panel presents boxplots for all agents, the bottom left panel for BCMA agents, and bottom right panel for GPRC5D/FcRH5 agents, with Chi-square statistics, p-values, and degrees of freedom shown on top of each panel. No statistically significant p-values were observed in the pairwise agent’s comparison with Wilcoxon signed-rank tests.

Clustering

Our clustering analysis includes thirty-four BCMA, GPRC5D/FcRH5, BCMA × GPRC5D, Tal + Pom, and Tal + Dara agents shown in different colors in Fig. 3. Upon clustering these agents, we found differences in their AE performance across all grades. The visualizations (Fig. 3) highlight differences in AE profiles among the agent groups. In both PCA plots, BCMA agents (e.g., Tec, TecU1, Elr, Aln) formed a tight cluster, showing high AE profile consistency and GPRC5D/FcRH5 agents were more expanded, displaying greater diversity. Notably, Tec + Tal, Tal + Dara, and Tal + Pom each formed clearly separated clusters. The clustering patterns were consistent between any grade and grade 3/4 AEs plots, showing that pharmacological mechanism (BCMA vs. GPRC5D/FcRH5) drove grouping regardless of AE severity. Grade 3/4 PCA appears more compact than any grade PCA, indicating less variability in high-grade AEs across agents. In the grade 3/4 plot, the Tec + Tal cluster shifts closer to other GPRC5D/FcRH5 agents, implying a greater similarity in their severe AE profiles.

Discussion

Our pooled analysis revealed significant differences in the AE profiles between BCMA-targeting and GPRC5D/FcRH5 BsAbs. These findings are crucial for optimizing patient management, counseling for side effects, and therapy selection for patients who have failed multiple lines of treatment. The main AEs were hematologic, infections, CRS, and neurotoxicity. The safety analysis revealed distinct AE profiles between BCMA and GPRC5D/FcRH5 BsAbs. While hematologic toxicities (e.g., neutropenia, anemia) and infections were more frequent with BCMA-directed therapies, GPRC5D/FcRH5 agents showed higher rates of CRS. The Talquetamab-containing combination group had the highest overall AE burden but the lowest grade 3/4 anemia.

From the pooled analysis Figs. 1 and 2, we conclude that the BCMA group shows more variability and higher responses in certain agents compared to the GPRC5D/FcRH5 group. Across all plots, the generalized Friedman test indicates statistically significant differences in responses among agents. Agents with higher medians or larger spread might warrant further investigation for their effectiveness or variability. The differences between BCMA and GPRC5D/FcRH5 groups suggest that BCMA agents may be more potent or sensitive but with greater variability in their effects. GPRC5D/FcRH5 agents may offer more predictable and consistent outcomes, potentially making them preferable for scenarios requiring stability. Agents with separated from the rest or wide distributions could be explored further to understand their unique impact or variability.

Also, Fig. 3 highlights distinct clustering patterns among agents based on AE profiles. Notably, combination therapies such as Tec + Tal, Tal + Dara, and Tal + Pom form well-separated clusters, likely reflecting their unique pharmacological profiles and combined immunomodulatory effects. These agents target multiple mechanisms simultaneously, which may explain their distinct AE signatures and clustering behavior. In contrast, a couple of agents appear isolated from their expected group clusters. TecJPh2, for instance, separates from its counterpart TecJPh1, which demonstrates a substantially higher proportion of reported deaths (27% vs. 0%) and a significantly lower incidence of t(4;14) translocation (0% vs. 36%). TecJPh2 also shows approximately one-third the reporting frequency for insomnia, high-risk cytogenetics, and neurotoxicity, while exhibiting about 2.5-fold higher reporting ratios for hypogammaglobulinemia and nasopharyngitis. Another separation, Tal_TCR, includes patients previously exposed to T-cell redirection therapies and subsequently treated with the recommended subcutaneous talquetamab doses, 0.4 mg/kg weekly (Tal_0.4) or 0.8 mg/kg biweekly (Tal_0.8) [29]. Tal_TCR shows 17% stomatitis and upper respiratory tract infection vs only 1% Tal_0.4, 12% vs 1% for back pain and hypotension, and 10% vs 1% for increased alanine aminotransferase. Hypokalemia and steroid-treated CRS were approximately four times more frequent in Tal_TCR compared to Tal_0.4. Conversely, grade 3/4 fatigue and ICANS were reported at roughly one-third the frequency observed in Tal_0.4. Lastly, a comparison of ABBVID and ABBVLD reveals that ABBVID is associated with 20% CR rates vs 2% for ABBVLD. In addition, CRS, vomiting, neutropenia, lymphopenia, grade 3/4 neutropenia, ORR, nausea, anemia, and diarrhea are reported approximately twice as frequently in ABBVID. Conversely, ABBVID shows about four times lower PR rates and roughly half the incidence of death compared to ABBVLD.

Hematologic AEs, particularly cytopenias (leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia) were observed at high rates across both BCMA and GPRC5D/FcRH5 BsAbs. These cytopenia AEs are mostly seen with the use of BsAbs during the first treatment cycle2. Grade 3/4 neutropenia occurred in 35.17% of patients, which poses a significant risk for infection, and in many cases dose modifications, and close monitoring of febrile neutropenic episodes, supportive care interventions such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) administration in certain cases. Moreover, a recent pooled analysis found higher rates of grade 3-4 hematologic toxicities in BCMA-targeting agents, than their counterparts. Similar trends were observed in our study, as grade 3-4 neutropenia and anemia were most frequently reported in patients receiving teclistamab and elranatamb. These complications, namely neutropenia-related infections, can be potentially life-threatening and result in treatment delays and dose reductions, which in turn can affect treatment efficacy [40].

Infections (45.75%) demonstrated distinct patterns across treatment groups, with the highest all-grade incidence occurring in talquetamab-containing combinations, followed by BCMA×GPRC5D BsAbs. Notably, single-target BCMA agents showed higher infection rates (45.3% all-grade, 21.63% grade 3-4) compared to GPRC5D/FcRH5 therapies (42.57% all-grade, 14.51% grade 3-4). This finding likely reflects both the concurrent expression of BCMA on mature B cells and plasma cells and the T-cell exhaustion resulting from constant immune stimulation [41]. The constant stimulation of T-cells by these agents can also cause T-cell exhaustion and lead to the dampening of T-cell-mediated immunity [41]. This observation highlights the need for infection prophylaxis, especially in patients receiving long-term BsAbs therapy. These include the implementation of prophylactic antimicrobial agents including antiviral and PJP prophylaxis, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) (3.62) replacement therapy, and vigilant monitoring for early signs of sepsis. Furthermore, it was shown that MM patients are at high risk of severe COVID-19 (3.71) infection and related mortality, especially in the setting of BCMA-targeted therapies. This highlights the vulnerability of MM patients, especially those on anti-BCMA agents to viral infections, which would influence infection control measures and vaccination decisions [42].

CRS, a well-documented AE of BsAbs, was observed in up to 64.95% of patients. CRS arises from robust activation of cytotoxic T-cells and the release of inflammatory cytokines. It can manifest with a wide spectrum of presentations, ranging from mild, flu-like symptoms, such as fatigue, headache, and myalgias; to severe, life-threatening symptoms, such as hemodynamic instability, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and multi-organ system failure [43]. In various bispecific antibody trials, all-grade CRS has been reported in 28–89% with median 71.5% of patients, while grade 3 or higher CRS incidence rate was lower (0–7%) with median 1% but for GPRC5D/FcRH5 agents CRS grade 3/4 were reported at 1.66%.

BCMA-targeting agents were associated with fewer CRS events (56.82%) as compared to GPRC5D/FCRH5-targeting agents (73.13%), and combinations (BCMA × GPRC5D: 79.62%, Tal + Dara: 77%). Most CRS events occur after the first full dose. To mitigate this risk, careful monitoring, step-up dosing with premedication, and the judicious use of steroids (6.91), tocilizumab (24.14), and dose delays have been recommended. Prophylactic administration of a single dose of tocilizumab has significantly reduced CRS incidence without affecting treatment efficacy, as demonstrated in a sub-cohort of the MajesTEC-1 study [44]. The ability to effectively manage CRS is pivotal in expanding the use of BsAbs in the outpatient setting without affecting the treatment regimen [40].

ICANS (3.96), though less frequent than CRS (64.95), remains a well-documented complication of CAR T cells and BsAbs. The incidence of ICANS, commonly presenting as mild to moderate confusion and dysgraphia, was more common in GPRC5D/FCRH5-targeting agents, namely talquetamab. Given the potential for ICANS to impact a patient’s quality of life, early identification and management of this toxicity are essential. Corticosteroids are the first line treatment for ICANS, with the addition of tocilizumab in patients with ICANS co-occurring with CRS [32].

Distinct toxicity profiles of BCMA and GPRC5D/FcRH5 BsAbs offer opportunities for personalized treatment. BCMA-targeting agents, namely teclistamab and elranatamab, present with higher hematologic and infection risks, and may require closer monitoring and prophylactic measures. Conversely, GPR5CD-targeting agents are more likely to be associated with CRS. In Phase 2 studies, skin-related AEs were reported in 69%, nail-related AEs (61%), and dysgeusia (61%). These unique on-tumor-off target toxicities are distinct and usually not severe and rarely need treatment discontinuation. However, these side effects can negatively affect the quality of life and pose potential challenges for therapy selection for relapse/relapse MM [30].

Clinical implications

Our study provides an analysis of safety and efficacy from the pooled analysis. We have learned that the use of prophylactic IVIG has significantly reduced the risk of infections in patients receiving bispecific antibodies [45]. For high-grade neutropenia, G-CSF can be safely utilized after stepping up dosage. Similarly, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) can be used for Hb <10 g/dl, while thrombopoietin-mimetics should be considered selectively for severe thrombocytopenia [46]. Grade 2 or higher CRS can be treated with tocilizumab 10 mg/kg every 8 hours with or without dexamethasone 10 mg every 6 hours. ICANS is managed with dexamethasone 10 mg every 6 hours and then tapered down upon symptom improvement [47]. For prolonged grade 3 or 4 ICANS, it is recommended to add Anakinra 100-200 mg every 8 hours in addition to steroids [47].

Regarding dysgeusia, we did not identify any successful approaches in our pooled analysis to mitigate these side effects, however, real-world data suggest decreasing the frequency of talquetamab to q4w and prophylactic use of dexamethasone mouth rinses and nystatin mouthwash or zinc and vitamin B complex may be effective strategies to alleviate oral symptoms [48].

Our analysis provides a comprehensive assessment of standardized adverse events reporting and can inform future studies focusing on specific adverse events like skin, hair or nail toxicities or taste alterations from talquetamab as well as efforts to control increase rate of infections and strategies to employ different dosing and/or fixed duration of treatment of BCMA and non BCMA bispecific Abs. Our findings further underscore the dynamic nature of bispecific antibody research in multiple myeloma and highlight the importance of continuous data synthesis like collaborative Individual patient data (IPD) studies to enable propensity matching and adjust for confounders including prior treatment intensity or comorbidities, a limitation inherent to our current aggregated data. We believe these steps will bridge the gaps identified in this study while advancing the field toward personalized therapeutic selection.

Limitations

Our analysis faced limitations due to a significant number of unreported missing values in the underlying studies and a lack of access to patient-level data. This shortage of data prevented the use of multivariate or propensity score-matched analyses to adjust for potential confounders. In their place, we applied non-parametric methods—specifically the Skillings-Mack test and Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test—to handle missing and unbalanced data while accounting for inter-trial variability. These methods align with current best practices for meta-analyses using aggregated data and allow us to conduct robust group comparisons without relying on parametric assumptions. Nonetheless, we recognize that these approaches cannot fully control for confounding, and we highlight the need for future analyses using individual-patient-level data.

Also, some studies, especially those focused on infection-related AEs, either omitted or did not fully report these details, leading to many missing values. Additionally, some studies, driven by specific goals, neglected to report essential details, concentrating only on efficacy and a few AEs. Many abstracts also reported retests of other publications without providing baseline characteristics, further contributing to missing values in our analyses. Missing data poses a threat to the integrity of clinical research, potentially leading to biased results and reduced statistical power [49]. In our analysis, missing data was addressed by normalizing each agent with its total population to scale the values ranging within a similar interval, in this case between 0 and 1. Following the normalization process, we utilized the ranked matrix generated by the Skillings Mack test on our dataset, which handled all missing values.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kleber M, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Terpos E. BCMA in multiple myeloma—a promising key to therapy. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4088.

Harris M. Monoclonal antibodies as therapeutic agents for cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:292–302.

Hosny M, Verkleij CPM, van der Schans J, Frerichs KA, Mutis T, Zweegman S, et al. Current state of the art and prospects of T cell-redirecting bispecific antibodies in multiple myeloma. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4593.

Gandhi UH, Cornell RF, Lakshman A, Gahvari ZJ, McGehee E, Jagosky MH, et al. Outcomes of patients with multiple myeloma refractory to CD38-targeted monoclonal antibody therapy. Leukemia. 2019;33:2266–75.

Yu B, Jiang T, Liu D. BCMA-targeted immunotherapy for multiple myeloma. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:125.

Rodriguez-Otero P, van de Donk N, Pillarisetti K, Cornax I, Vishwamitra D, Gray K, et al. GPRC5D as a novel target for the treatment of multiple myeloma: a narrative review. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14:24.

Jaberi-Douraki M, Xu X, Faiman B, Wyckoff G, Riviere J, Khouri J, et al. Disparities in multiple myeloma: a global perspective on drug toxicity trends. ASCO J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:8015.

Jaberi-Douraki M, Xu X, Dima D, Ailawadhi S, Anwer F, Mazzoni S, et al. Global disparities in drug-related adverse events of patients with multiple myeloma: a pharmacovigilance study. Blood cancer J. 2024;14:223.

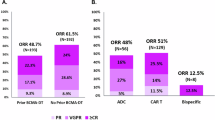

Jaberi-Douraki M, Raza S, Xu X, Ramachandran RA, Golmohammadi M, Sholehrasa H, et al. Comparative analysis of adverse event profiles for CAR-T cell therapies and bispecific antibodies in lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43.

Jaberi-Douraki M, Xu X, Ramachandran R, Faiman B, Anwer F, Samaras C, et al. Global disparities in multiple myeloma: examining adverse events and drug toxicity trends. Clin Lymphoma, Myeloma Leuk. 2023;23:S295–6.

SERVICES USDOHAH. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). 2017. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae_v5_quick_reference_5x7.pdf.

Moreau P, Garfall AL, van de Donk NWCJ, Nahi H, San-Miguel JF, Oriol A, et al. Teclistamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:495–505.

Venkatesh P, Atrash S, Paul B, Alkharabsheh O, Afrough A, Mahmoudjafari Z, et al. Efficacy of teclistamab in patients (pts) with heavily pretreated, relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM), including those refractory to penta RRMM and BCMA (B-cell maturation antigen) directed therapy (BDT). J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:e20044.

Rifkin R, Schade H, Simmons G, Yasenchak C, Fowler J, Lin TS, et al. Optec: a phase 2 study to evaluate outpatient step-up administration of teclistamab in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): updated results. Blood. 2024;144:4753.

Ishida T, Kuroda Y, Matsue K, Komeno T, Ishiguro T, Ishikawa J, et al. A phase 1/2 study of teclistamab, a humanized BCMA×CD3 bispecific Ab in Japanese patients with relapsed/refractory MM. Int J Hematol. 2025;121:222–31.

Firestone R, Shekarkhand T, Patel D, Tan CRC, Hultcrantz M, Lesokhin AM, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of commercial teclistamab in relapsed refractory multiple myeloma patients with prior exposure to anti-BCMA therapies. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:8049.

Lesokhin AM, Tomasson MH, Arnulf B, Bahlis NJ, Miles Prince H, Niesvizky R, et al. Elranatamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: phase 2 MagnetisMM-3 trial results. Nat Med. 2023;29:2259–67.

Sun M, Qiu L, Wei Y, Jin J, Li X, Liu X, et al. Results from a first-in-human phase I study of F182112, a B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-CD3 bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:8038.

Zonder JA, Richter J, Bumma N, Brayer J, Hoffman JE, Bensinger WI, et al. Early, deep, and durable responses, and low rates of cytokine release syndrome with REGN5458, a BCMAxCD3 bispecific monoclonal antibody, in a phase 1/2 first-in-human study in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Blood. 2021;138:160.

Bumma N, Richter J, Jagannath S, Lee HC, Hoffman JE, Suvannasankha A, et al. Linvoseltamab for treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:2702–12.

Lee HC, Bumma N, Richter JR, Dhodapkar MV, Hoffman JE, Suvannasankha A, et al. LINKER-MM1 study: linvoseltamab (REGN5458) in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:8006.

Bumma N, Richter J, Brayer J, Zonder JA, Dhodapkar M, Shah MR, et al. Updated safety and efficacy of REGN5458, a BCMAxCD3 bispecific antibody, treatment for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: a phase 1/2 first-in-human study. Blood. 2022;140:10140–1.

Topp MS, Duell J, Zugmaier G, Attal M, Moreau P, Langer C, et al. Anti–B-cell maturation antigen BiTE molecule AMG 420 induces responses in multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:775–83.

Harrison SJ, Minnema MC, Lee HC, Spencer A, Kapoor P, Madduri D, et al. A phase 1 first in human (FIH) study of AMG 701, an anti-B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) half-life extended (HLE) BiTE® (bispecific T-cell engager) molecule, in relapsed/refractory (RR) multiple myeloma (MM). Blood. 2020;136:28–9.

Costa LJ, Wong SW, Bermúdez A, de la Rubia J, Mateos M-V, Ocio EM, et al. First clinical study of the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) 2+1 T cell engager (TCE) CC-93269 in patients (Pts) with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): interim results of a phase 1 multicenter trial. Blood. 2019;134:143.

D’Souza A, Shah N, Rodriguez C, Voorhees PM, Weisel K, Bueno OF, et al. A phase I first-in-human study of ABBV-383, a B-cell maturation antigen × CD3 bispecific T-cell redirecting antibody, in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:3576–86.

Chari A, Minnema MC, Berdeja JG, Oriol A, van de Donk N, Rodriguez-Otero P, et al. Talquetamab, a T-cell-redirecting GPRC5D bispecific antibody for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:2232–44.

Chari A, Touzeau C, Schinke C, Minnema MC, Berdeja JG, Oriol A, et al. Safety and activity of talquetamab in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MonumenTAL-1): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1-2 study. Lancet Haematol. 2025;12:e269–81.

Krishnan AY, Minnema MC, Berdeja JG, Oriol A, van de Donk NWCJ, Rodriguez-Otero P, et al. Updated phase 1 results from MonumenTAL-1: first-in-human study of talquetamab, a G protein-coupled receptor family C group 5 member D x CD3 bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2021;138:158.

Schinke CD, Touzeau C, Minnema MC, van de Donk NW, Rodríguez-Otero P, Mateos MV, et al. Pivotal phase 2 MonumenTAL-1 results of talquetamab (tal), a GPRC5DxCD3 bispecific antibody (BsAb), for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:8036.

Trudel SCA, Krishnan AY, Fonseca R, Spencer A, Berdeja JG, Lesokhin A, et al. Cevostamab monotherapy continues to show clinically meaningful activity and manageable safety in patients with heavily pre-treated relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): updated results from an ongoing phase I study. Blood. 2021;138:157.

Cohen YCMD, Gatt ME, Sebag M, Kim K, Min CK, Oriol A, et al. First results from the RedirecTT-1 study with teclistamab (tec)+ talquetamab (tal) simultaneously targeting BCMA and GPRC5D in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:8002.

Cohen YC, Magen H, Gatt M, Sebag M, Kim K, Min CK, et al. Talquetamab plus teclistamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:138–49.

Dholaria BR, Weisel K, Mateos MV, Goldschmidt H, Martin TG, Morillo D, et al. Talquetamab (tal)+ daratumumab (dara) in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): updated TRIMM-2 results. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:8003.

Matous J, Biran N, Perrot A, Berdeja JG, Dorritie K, Van Elssen J, et al. Talquetamab plus pomalidomide in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: safety and preliminary efficacy results from the phase 1b MonumenTAL-2 Study. Blood. 2023;142:1014.

Chatfield M, Mander A. The Skillings-Mack test (Friedman test when there are missing data). Stata J. 2009;9:299–305.

Gewers FL, Ferreira GR, Arruda HFD, Silva FN, Comin CH, Amancio DR, et al. Principal component analysis: a natural approach to data exploration. ACM Comput Surv. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1145/344775.

Greenacre M, Groenen PJF, Hastie T, D’Enza AI, Markos A, Tuzhilina E. Principal component analysis. Nat Rev Methods Prim. 2022;2:100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-022-00192-w.

Pearson K. LIII. On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. Lond Edinb Dublin Philos Mag J Sci. 1901;2:559–72.

Raje N, Anderson K, Einsele H, Efebera Y, Gay F, Hammond SP, et al. Monitoring, prophylaxis, and treatment of infections in patients with MM receiving bispecific antibody therapy: consensus recommendations from an expert panel. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13:116.

Yu G, Boone T, Delaney J, Hawkins N, Kelley M, Ramakrishnan M, et al. APRIL and TALL-I and receptors BCMA and TACI: system for regulating humoral immunity. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:252–6.

Terpos E, Musto P, Engelhardt M, Delforge M, Cook G, Gay F, et al. Management of patients with multiple myeloma and COVID-19 in the post pandemic era: a consensus paper from the European Myeloma Network (EMN). Leukemia. 2023;37:1175–85.

Tvedt THA, Vo AK, Bruserud O, Reikvam H. Cytokine release syndrome in the immunotherapy of hematological malignancies: the biology behind and possible clinical consequences. J Clin Med. 2021;10:5190.

Trudel S, Bahlis NJ, Spencer A, Kaedbey R, Rodriguez Otero P, Harrison SJ, et al. editor Pretreatment with tocilizumab prior to the CD3 bispecific cevostamab in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) showed a marked reduction in cytokine release syndrome incidence and severity. Blood. 2022;140:1363–5.

Lancman G, Parsa K, Kotlarz K, Avery L, Lurie A, Lieberman-Cribbin A, et al. IVIg use associated with ten-fold reduction of serious infections in multiple myeloma patients treated with anti-BCMA bispecific antibodies. Blood Cancer Discov. 2023;4:440–51.

Pan D, Richter J. Management of toxicities associated with BCMA, GPRC5D, and FcRH5-targeting bispecific antibodies in multiple myeloma. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2024;19:237–45.

Rees JH. Management of immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). In: Kroger N, Gribben J, Chabannon C, Yakoub-Agha I, Einsele H, editors. The EBMT/EHA CAR-T cell handbook. Springer Nature Switzerland AG Cham; 2022. pp. 141–5.

Schinke C, Dhakal B, Mazzoni S, Shenoy S, Scott SA, Richards T, et al. Real-world experience with clinical management of talquetamab in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: a qualitative study of US healthcare providers. Curr Med Res Opin. 2024;40:1705–11.

Groenwold RHH, Dekkers OM. Missing data: the impact of what is not there. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;183:E7–9.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the K-State Olathe program and its support for the 1DATA Consortium at Kansas State University, as well as by BioNexus KC [BioNexus KC 20-7 Nexus of Animal and Human Health Research Grant]. Neither K-State Olathe nor BioNexus KC had a direct role in this article.

Funding

MJD accepted funding from BioNexus KC for this project (BioNexus KC 20-7 Nexus of Animal and Human Health Research Grant).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: MJD, SR; Methodology: MJD, MG, HS, MA, XX, FA, SR; Software: MG, HS, MA, MJD; Validation: MG, HS, MA, MJD; Data curation and acquisition: MG, HS, MA, MJD, SR, DD, AM; Formal analysis: MG, HS, MA, MJD, SR; Writing—original draft: MG, HS, MA, MJD; Writing—review and editing: SR, JK, LW, DKH, AM, XX, MoA, AHA, DD, FA, BP; Visualization: MG, HS, MA; Resources and supervision: MJD, SR, FA; Project administration: MJD, SR; Funding acquisition: MJD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

SR received an honorarium as an advisory board for Pfizer, Prothena Biosciences, KiTE pharma Nexcella and Janssen and received research funding (outside of this study) from Nexcella Inc, Poseida Therapeutics and Janssen. JK: Consultancy and honoraria: Janssen, GPCR therapeutics, and Prothena. LW is a local principal investigator for Pfizer and Abbvie clinical trials and received honorarium for advisory board meeting for Janssen/J&J Consulting. DH is supported by the NCI (R01CA281756-01A1) and the Pentecost Family Myeloma Research Center and reports research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Karyopharm, Kite Pharma, and Adaptive Biotech; Consulting or advisory role for Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, Kite Pharma, AstraZeneca, and Karyopharm. FA served as the local principal investigator for Allogene Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, and GlaxoSmithKline and served as the advisor and speaker for Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene. Other authors declare non-relevant declare non-financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Golmohammadi, M., Raza, S., Albayyadhi, M. et al. Comprehensive assessment of adverse event profiles associated with bispecific antibodies in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 15, 130 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01334-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01334-5

This article is cited by

-

BCMA and GPRC5D/FcRH5 bispecific antibodies have different AE profiles

Reactions Weekly (2025)