Abstract

The Iceland Screens, Treats, or Prevents Multiple Myeloma (iStopMM) risk stratification model, developed to predict ≥10% abnormal plasma cells in the bone marrow in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) patients, was developed in a predominantly White and genetically homogeneous Icelandic population, lacking external validation. Our study aimed to externally validate this model in a racially and ethnically diverse Bronx population. The medical records of patients at Montefiore Medical Center (2002–2023) were searched to identify patients with MGUS who had undergone a bone marrow biopsy. For each patient, the iStopMM variables were entered into the iStopMM prediction model, and predicted, and actual plasma cell percentages were recorded. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve assessed the iStopMM model’s performance in predicting ≥10% plasma cells, and sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated. Of the initial 663 patients, 190 were included in the final cohort, of whom 52.6% were African-Americans, and 23.2% identified themselves as Hispanic/Latino, remarkably different from the homogenous population of the iStopMM study. The iStopMM predictive model was able to predict greater than or equal to 10% plasma cells on bone marrow biopsy with an AUROC of 0.78 (CI 0.71, 0.85). When set at a 10% threshold for predicting SMM or worse, the iStopMM model had a 93.3% sensitivity, 33.7% specificity, 55.3% PPV, and 85.0% NPV. This AUROC value of 0.778 suggests a reasonable discriminatory performance of the model in our racially and ethnically diverse Bronx population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is a pre-malignant condition involving abnormal plasma cells, marked by the presence of a monoclonal (M) protein, less than 10% of plasma cells in the bone marrow, and the absence of multiple myeloma (MM) or similar lymphoplasmacytic malignancies (LPMs) [1]. In the United States, about 3% of people over 50 have MGUS [2]. Smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM) is an asymptomatic transitional phase between MGUS and MM, characterized by an M protein concentration equal to or exceeding 30 g/L and/or bone marrow plasma cells ranging from 10% to 60%, without any myeloma-defining events or amyloidosis [1]. It is less common than MGUS, affecting around 0.5% of individuals aged 40 and above [3]. MGUS carries a risk of evolving into MM or related malignancies at a rate of around 1% annually, whereas SMM presents a significantly higher risk of progression, approximately 10% annually for the first five years [4,5,6].

There is inconsistency in guidelines regarding the extent of initial assessment and subsequent monitoring of MGUS due to limited high-quality evidence [7,8,9]. The Mayo Clinic’s risk stratification model, which relies on three primary risk factors: an abnormal serum free light chain ratio, a high serum M protein level (≥1.5 g/dL), and non-immunoglobulin G(IgG) MGUS, is one of the most widely utilized risk stratification models [4, 10]. Recently, the Iceland Screens, Treats, or Prevents Multiple Myeloma (iStopMM) initiative, a population-based screening study for MGUS in Iceland, developed a multivariable proportional-odds logistic model to predict the likelihood of having 10% or more abnormal plasma cells in the bone marrow (suggestive of SMM or worse based on bone marrow criteria) in individuals with IgG, immunoglobulin A (IgA), or biclonal MGUS [11].

The iStopMM model utilizes the following predictors - MGUS subtype (IgG, IgA, biclonal), M protein concentration, free light chain ratio, and total IgG, IgA, and immunoglobulin M (IgM) levels [11]. When set at a 10% threshold for predicting SMM or worse, this model demonstrated an 86% sensitivity, 67% specificity, 32% positive predictive value, and 96% negative predictive value [11]. However, a notable limitation of the iStopMM model is its lack of external validation.

This is particularly significant given that the model was developed within the predominantly White and genetically homogeneous population of Iceland [11], which may not accurately represent the ethnic and racial diversity found in various population subsets within the United States. In addition, the prevalence of MGUS is 2 to 3 times higher in the African–American patient population [12, 13]. Hence, it is essential to evaluate whether these results apply to this patient population. Therefore, our study aims to validate this model within a racially diverse patient population in the Bronx.

Methods

Data source and study population

The electronic medical records of patients receiving care at Montefiore Medical Center from 2002 to 2023 were searched to identify patients with a diagnosis of MGUS using the International Code of Diseases (ICD-10 code D47.2 and the ICD-9 code 273.1) and who had undergone a bone marrow biopsy.

Each patient chart was manually verified to identify and exclude patients not meeting the diagnostic criteria for MGUS as per the updated International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria [1]. Further, amongst MGUS patients, the following patients were excluded: patients without a bone marrow (BM) biopsy result available, suboptimal BM biopsy, patients with IgM

MGUS, unclear immunoglobulin isotype, unavailable free light chain ratio, or unavailable SPEP. Hence, a final cohort of MGUS patients with all variables and bone marrow biopsy results available was created.

Outcome variables

The following variables from each patient chart, closest to the time of bone marrow biopsy, were entered in the iStopMM prediction model available at https://istopmm.com/riskmodel/: MGUS isotype (IgG, IgA, biclonal), M protein concentration, free light chain ratio, and total IgG, IgA, and IgM concentrations. The predicted % of plasma cells was obtained by entering these values in the prediction model and recorded in the datasheet. The actual % of plasma cells obtained from the original bone marrow biopsy specimen was also recorded in the datasheet.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were reported using frequencies for categorical values and medians for continuous variables. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve was used to assess the performance of the iStopMM prediction model in our cohort, with the binary variable being whether greater than or equal to 10% of plasma cells were detected on bone marrow biopsy. The value of the AUROC curve ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating 100% discriminatory accuracy. Within our cohort, we evaluated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) for identifying patients with 10, 20, and 50% probability of having greater than or equal to 10% plasma cells based on the iStopMM prediction model. Additionally, the optimal cut-point for our populations was calculated using Youden’s index. All statistical analysis was completed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 29.0.

Results

Cohort characteristics

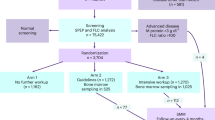

Of the initial six hundred and sixty-three patients, a total of 190 were included in the final cohort. As shown in Fig. 1, the major exclusions were patients who met the criteria for MM (n = 325), those with hematologic conditions other than MGUS/MM (n = 53), and those whose SPEP had no M-protein detected (n = 24). Further, we excluded those MGUS patients whose BM biopsy was either unavailable (n = 14) or suboptimal (n = 4), who had IgM monoclonal protein (n = 23), whose M-protein isotype was unclear (n = 21), or those patients without available FLC ratio (n = 3) or SPEP (n = 6).

Table 1 demonstrates the baseline characteristics of the MGUS cohort, comprising 190 individuals, 55.8% of whom were females and 44.2% males. The median age was 75 (interquartile range 65–83). In terms of race, the majority of individuals were African-Americans (52.6%), followed by individuals categorized as Others (22.1%), Whites (14.7%), Unknown (8.4%), and Asians (2.1%). Regarding ethnicity, a majority identified as non-Hispanic/Latino (68.4%), 23.2% as Hispanic/Latino, and 8.4% were unknown ethnicity. Based on the bone marrow biopsy results, 91 (47.9%) patients had SMM, and 99 (52.1%) had MGUS. Analysis of immunoglobulin isotypes among the MGUS cohort indicates a prevalent distribution of IgG (83.7%), followed by IgA (11.1%). A smaller proportion of individuals exhibit biclonal or light chain patterns, each representing 2.6% of the cohort.

The receiver operating curve analysis

The iStopMM predictive model was able to predict greater than or equal to 10% plasma cells on bone marrow biopsy with an AUROC of 0.78 and confidence interval (0.71, 0.85) (Fig. 2).

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. ROC receiver operating characteristic, iStopMM Iceland screens, treats, or prevents multiple myeloma,Std. Error standard error, Asymptotic Sig. asymptotic significance level, Sens sensitivity, Specspecificity, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value.

Within our cohort, we evaluated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) for identifying patients with a 10%, 20%, and 50% chance of having greater than or equal to 10% plasma cells on bone marrow biopsy, as mentioned in Fig. 2.

When set at a 10% threshold for predicting SMM or worse, the iStopMM model has a 93.3% sensitivity, 33.7% specificity, 55.3% PPV, and 85.0% NPV. Additionally, the optimal cut-point by Youden’s index was calculated to be 33%, indicating that within our population, the sensitivity (70.8%) and specificity (77.2%) are optimal when the threshold is set at a 33% chance of having greater than or equal to 10% plasma cells on bone marrow biopsy by the IStopMM model.

Discussion

Since MGUS is a pre-malignant condition with approximately 1% annual risk of evolving into MM, a critical aspect in the care of MGUS patients is risk stratification and monitoring [5, 6]. The IMWG risk stratification system utilizes these three factors to predict the risk of progression of MGUS to MM or a related malignancy - serum M-protein level ≥15 g/L, abnormal serum FLC ratio, and non-IgG MGUS [7]. According to this model, the absolute risk of progressing to MM over 20 years increases to 5%, 21%, 37%, and 58% when zero (low-risk MGUS), one (low- intermediate risk MGUS), two (high-intermediate risk MGUS), and three (high-risk MGUS) risk factors are present, respectively [4, 7, 10, 14].

An essential question for MGUS patients is to identify those patients who would require a bone marrow biopsy since it is sometimes the only way to distinguish MGUS patients from those with SMM. As per the IMWG guidelines, a baseline BM biopsy is indicated in most MGUS patients except those with low-risk features [7]. However, bone marrow biopsy is a resource-intensive, potentially unpleasant procedure typically limited to specialized facilities [15]. Moreover, this recommendation is based on the predicted absolute risk of developing MM over 20 years. Still, it does not directly consider the clinically relevant question of predicting the risk of having ≥10% plasma cells if an MGUS patient underwent BM biopsy, which the newer iStopMM model addresses.

The iStopMM initiative is a population-based screening effort for MGUS in Iceland, which extended invitations to all Icelanders born in 1975 or earlier to participate in the study [11]. This screening project obtained blood samples from 75,422 individuals aged 40 or older, encompassing 51% of the Icelandic populace, and detected 3788 cases of MGUS, with 2607 of these cases enrolled for active follow-up [11]. Out of these 2607 cases, data from a total of 1043 participants was utilized to create the iStopMM multivariate model, which, unlike the Mayo Clinic model, involves the entry of actual patient-specific numeric values into the risk calculator.

Utilizing this model to postpone bone marrow biopsy for individuals with estimated bone marrow involvement of less than 10 percent would permit 58.8 percent of the population to delay the procedure. Among them, 3.6 percent would receive a diagnosis of SMM, while none would be identified with MM during biopsy [11]. A comparison within this Scandinavian population suggested that the iStopMM model would enable more participants to bypass unnecessary bone marrow sampling compared to the Mayo Clinic model [11].

In our study, we aimed to externally validate the iStopMM model, which was designed in the genetically homogenous population of Iceland, in the racially and ethnically diverse population of the Bronx. Such external validation is crucial to demonstrate the model’s generalizability when utilized beyond the original population since differences in patient demographics, environmental factors, and local resources could impact the performance of a prediction model [16, 17]. Our study cohort included 52.6% of patients identifying as African–American and 23.2% as Spanish/Hispanic/Latino, highlighting the unique patient composition. We utilized AUROC as our primary metric to assess the iStopMM prediction model’s performance, with the binary variable being greater than or equal to 10% of plasma cells detected on bone marrow biopsy.

The c-statistic, which is equivalent to AUROC value for binary outcomes, for the original IStopMM Model was 0.85 (CI 0.82–0.89) within the Icelandic population [11, 18]. When implemented in our Bronx population, the iStopMM model was able to predict the chance of detecting SMM or worse on bone marrow biopsy with an AUROC of 0.778 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.71–0.85. This AUROC value of 0.778 suggests a reasonable discriminatory performance of the model in our racially and ethnically diverse study population. Moreover, the narrow confidence interval of 0.71–0.81 of the AUROC further underscores the consistency in the model’s performance.

At a threshold of 10% predicted risk of SMM or worse, the original iStopMM, when implemented in the Icelandic population, had a sensitivity of 85%, specificity of 67%, negative predictive value of 96%, and a positive predictive value of 32%. When set at the same threshold in our Bronx population, the iStopMM model has a sensitivity of 93.3%, specificity of 33.7%, negative predictive value of 85%, and a positive predictive value of 55.3% The difference in sensitivity for our population suggests that the model is more sensitive but less specific for our patient population. At a threshold of 33% (the optimal cut-point identified by Youden’s index in our population), the iStopMM model has a sensitivity of 70.8% and a specificity of 77.2%. This threshold of 33% predicted risk of SMM or worse optimized the balance between sensitivity and specificity, making it a more clinically relevant threshold in our population.

While our study provides valuable insights into the external validation of the iStopMM model in a diverse Bronx population, it has certain limitations. Our study was a retrospective data analysis of chart review, which is susceptible to inherent biases with data collection and restricts the investigator’s ability to account for changes in clinical practice over time. Since these tests were performed in the clinic only in patients who potentially had a clinical suspicion of a monoclonal gammopathy, our patient population is significantly different from the iStopMM population. In addition, the data does not capture information on time to bone marrow biopsy from the time an abnormal laboratory result is detected. This method of patient selection also gives a smaller sample size. Moreover, we utilized AUROC for analysis, which does not offer insights into the actual clinical utility or relevance in decision-making [19]. Finally, given the limited sample size, we could not explore the iStopMM model’s performance across different racial and ethnic subgroups or different MGUS isotypes. Further studies addressing such limitations and utilizing a different population subset could provide more insights into the external validity and clinical utility of the iStopMM model.

Data availability

The data presented in this manuscript will be available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author subject to the Montefiore Medical Center IRB data-sharing protocol.

References

Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Blade J, Merlini G, Mateos MV, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e538–48.

Mouhieddine TH, Weeks LD, Ghobrial IM. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 2019;133:2484–94.

Thorsteinsdottir S, Gislason GK, Aspelund T, Rognvaldsson S, Oskarsson J, Sigurethardottir GA, et al. Prevalence of smoldering multiple myeloma based on nationwide screening. Nat Med. 2023;29:467–72.

Kyle RA, Larson DR, Therneau TM, Dispenzieri A, Kumar S, Cerhan JR, et al. Long-term follow-up of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:241–9.

Kyle RA, Remstein ED, Therneau TM, Dispenzieri A, Kurtin PJ, Hodnefield JM, et al. Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2582–90.

Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, Offord JR, Larson DR, Plevak MF, et al. A long-term study of prognosis in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:564–9.

Kyle RA, Durie BG, Rajkumar SV, Landgren O, Blade J, Merlini G, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma: IMWG consensus perspectives risk factors for progression and guidelines for monitoring and management. Leukemia. 2010;24:1121–7.

Bird J, Behrens J, Westin J, Turesson I, Drayson M, Beetham R, et al. UK Myeloma Forum (UKMF) and Nordic Myeloma Study Group (NMSG): guidelines for the investigation of newly detected M-proteins and the management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). Br J Haematol. 2009;147:22–42.

van de Donk NW, Palumbo A, Johnsen HE, Engelhardt M, Gay F, Gregersen H, et al. The clinical relevance and management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and related disorders: recommendations from the European Myeloma Network. Haematologica. 2014;99:984–96.

Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Buadi FK. Advances in the diagnosis, classification, risk stratification, and management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: implications for recategorizing disease entities in the presence of evolving scientific evidence. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:945–8.

Eythorsson E, Rognvaldsson S, Thorsteinsdottir S, Einarsson Long T, Reed ER, Sigurdardottir GA, et al. Development of a multivariable model to predict the need for bone marrow sampling in persons with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance : a cohort study nested in a clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2024;177:449–57.

Landgren O, Gridley G, Turesson I, Caporaso NE, Goldin LR, Baris D, et al. Risk of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and subsequent multiple myeloma among African American and white veterans in the United States. Blood. 2006;107:904–6.

Landgren O, Katzmann JA, Hsing AW, Pfeiffer RM, Kyle RA, Yeboah ED, et al. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance among men in Ghana. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1468–73.

Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Melton LJ 3rd, Bradwell AR, et al. Serum free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 2005;106:812–7.

Degen C, Christen S, Rovo A, Gratwohl A. Bone marrow examination: a prospective survey on factors associated with pain. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:619–24.

Collins GS, Dhiman P, Ma J, Schlussel MM, Archer L, Van Calster B, et al. Evaluation of clinical prediction models (part 1): from development to external validation. BMJ. 2024;384:e074819.

Futoma J, Simons M, Panch T, Doshi-Velez F, Celi LA. The myth of generalisability in clinical research and machine learning in health care. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2:e489–e92.

Carrington AM, Fieguth PW, Qazi H, Holzinger A, Chen HH, Mayr F, et al. A new concordant partial AUC and partial c statistic for imbalanced data in the evaluation of machine learning algorithms. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2020;20:4.

Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, Gerds T, Gonen M, Obuchowski N, et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 2010;21:128–38.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RJ, JS, JW extracted data. RJ and PS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. PS analyzed the data. IM, MG, NK, LS, RG, DL, AS, MK, KG, EF, AV, RAS, IM, DC contributed to the draft preparation, MJ and NS conceptualized the project and supervised the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center (protocol code 2020–12559).

Informed consent statement

Patient consent was waived. Given the retrospective nature of the study, the main risk of harm to participants was the potential leak of protected health information. We had put in place specific data safe-keeping strategies to minimize this risk.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gor, R., Shivakumar, J., Surana, P. et al. Assessing the performance of the Iceland screens, treats, or prevents multiple myeloma (iStopMM) model in a multicultural Bronx cohort: implications for monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance risk stratification. Blood Cancer J. 15, 140 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01337-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01337-2