Abstract

Pomalidomide has been shown to improve survival in patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma (RRMM). However, the optimal pomalidomide-based combinations in RRMM are not known. This study compared pomalidomide, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone (PCD) with pomalidomide and dexamethasone (PD) in Asian patients with RRMM. Patients were randomly assigned to receive PCD or PD. Patients received pomalidomide at 4 mg from days 1 to 21, dexamethasone at 40 mg once a week, and those in the PCD arm received cyclophosphamide at 400 mg once weekly for three weeks. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival. One hundred and twenty-two patients were randomized (62 PCD, 60 PD). Baseline characteristics were comparable between both arms. The median prior lines of therapy were three. At a median follow-up of 13.5 (median range 9–18) months, median progression free survival was significantly longer at 10.9 months (95% confidence interval 7.1–27.7) in the PCD group compared with 5.8 months (95% CI, 4.4–6.9) in the PD group (hazard ratio 0.43; p < 0.001). Adverse events rates were similar in both arms. The most common grade ≥3 adverse events were hematological toxicities and pneumonia. 34 deaths occurred during the study (PCD: 17; PD: 17) and three were deemed to be related to study treatment. In Asian patients with RRMM after exposure to proteasome inhibitor and lenalidomide, progression-free survival was significantly prolonged with the addition of cyclophosphamide to PD, with a manageable safety profile.

Trial ID: Registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov: NCT03143049.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematologic malignancy characterized by clonal expansion of plasma cells in the bone marrow that produce monoclonal immunoglobulins [1]. The incidence of MM is approximately 180,000 cases globally and 73,000 in Asia [2].

Advances in treatment have significantly improved the survival of MM patients in the last 15 years [3]. However, despite these advances, MM remains incurable, and nearly all patients experience relapse at different stages of their disease [4]. In patients who relapse after the use of these novel agents, including bortezomib and lenalidomide, the survival is less than one year [5]. Access to new approved treatments and effective combinations is therefore critical to prolonging disease control and survival in myeloma patients. However, to most of the world, there is no access to newer treatments such as CAR-T and bispecific T-cell engagers, and access to daratumumab is limited by high cost. Pomalidomide has emerged as an important drug for relapsed myeloma. A randomized study of pomalidomide and dexamethasone compared with placebo and dexamethasone showed that pomalidomide can improve survival in this group of patients [6]. As a result, pomalidomide is now approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) for use in patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma (RRMM) previously treated with bortezomib and lenalidomide.

However, it is unclear what are the best drugs to combine with pomalidomide. Prior work by our group in a study using pomalidomide plus dexamethasone (PD) in Asian patients showed a progression-free survival (PFS) of nine months and an overall response rate (ORR) of 56.3% in the PD group with a favorable safety profile [7]. More importantly, for patients with suboptimal response to PD, a clinically meaningful response was achieved with the addition of oral cyclophosphamide (PCD), with a longer PFS of 10.8 months. In the United States (US), a small, randomized phase 2 study of PCD versus PD looking at the ORR as the primary endpoint showed that PCD has a higher ORR of 64.7% compared to 38.9% in PD, and correspondingly longer PFS of 9.5 months compared to 4.4 months in the PD arm [8]. To date, there are no randomized phase 3 studies between these regimens. This is an important step in obtaining data to compare the safety and efficacy of PCD over PD, as well as to establish if there are any statistically significant benefits of PCD over PD. We hypothesized that PCD would result in longer PFS than PD and should be one of the standard pomalidomide-containing regimens for relapsed myeloma patients. This combination is likely to be highly relevant not only to Asian patients, but also to patients in many other parts of the world, as cyclophosphamide is available as a low-cost, generic formulation, making the regimen broadly accessible.

Methods

Patients & study design

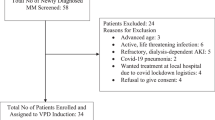

This was a randomized, two-arm, multicentre, multinational, prospective, open-label phase 3 study conducted by the Asian Myeloma Network (AMN). The study was approved by the Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB) in Singapore and the respective IRB of participating countries. Patients are enrolled after informed consent. The trial was registered in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03143049). In this study (AMN003), 122 patients were prospectively enrolled and randomized to receive PCD or PD. Centers in Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and Malaysia participated in this study.

Patients were eligible if they had RRMM, with prior exposure to lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor (PI), including bortezomib, carfilzomib, or ixazomib. Refractoriness was defined as disease progression on treatment or progression within six months of the last dose of a given therapy. Relapse is defined according to the criteria of the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) at study entry [9]. Other inclusion criteria were: age ≥18 years, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score of 0 to 2, and measurable disease. Patients could have received a maximum of six prior lines of treatment. Patients with plasma cell leukemia, circulating plasma cells ≥2 × 109/L or prior exposure to pomalidomide were excluded. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in (Supplementary Article).

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive PCD or PD. After completing screening and enrollment, subjects were randomly assigned by a computer algorithm to either PCD or PD. Randomization was stratified by country and International Stage System (ISS) stage (ISS stage I or II versus stage III), and randomly permuted block was used to ensure balance within each stratification factor. There was no blinding.

Drug Dosing

Drug dosing schedule was 4-weekly: oral pomalidomide 4 mg was given from day 1 – 21 and oral dexamethasone 40 mg once a week. Patients in the PCD arm received oral cyclophosphamide at a flat dose of 400 mg weekly for 3 weeks on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle (Fig. 1). Upon progression, patients randomized to the PD group could cross-over to the PCD arm, with cyclophosphamide started at the beginning of the next cycle. They could continue on PCD until further progression. Patients received treatment until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity as determined by the treating physician, consent withdrawal, or death.

Dexamethasone dose was reduced to 20 mg once a week in all subjects older than 75 years old. Dose modifications for dexamethasone were in accordance with the institutional guidelines. Concomitant use of bisphosphonates was allowed. Thromboprophylaxis with low-dose aspirin (100 mg or less) was allowed, although not mandated. Anti-microbial prophylaxis and the use of proton pump inhibitors were allowed according to institutional practice. Focal radiation therapy to lytic lesion for pain control was allowed.

Study overview

This study was sponsored by the International Myeloma Foundation. The study was performed in compliance with the requirements of the local regulatory authorities in Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia, and Japan, and was conducted in accordance with the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) regulations. Written informed consent in accordance with federal, local, and institutional guidelines was obtained from all subjects.

Endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS), defined as time from start of treatment to disease progression or death from any cause. The secondary endpoints were overall response rate (ORR, defined as the percentage of patients achieving partial response (PR) or better), overall survival (OS, the time from start of treatment to death from any cause), duration of response (DOR, time from first response to disease progression or death, whichever occurred first) in responders and safety, assessed by frequency of adverse events (AE). AEs were graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4. Responses were assessed per standard International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria [9].

Follow-up for disease status and survival proceeded until the subject withdrew consent, was lost to follow-up, died, or at study closure.

Statistical analysis

Sixty patients in each arm were needed to detect a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.5 for progression or death for PCD over PD, with a power of 80% and a two-sided level of significance of 5%. A modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population was used for analysis, which included all randomized patients receiving at least one dose of the study drug. PFS, OS, and DOR were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier methodology and the COX regression model. The ORR for each treatment group, difference of ORR between two treatments, its 95% confidence interval (CI), and p-value were estimated using a generalized linear model (GLM) with binomial distribution and identity link function. The GLM and COX models were adjusted for randomization stratification factors: country and ISS stage (stage I or II versus stage III). Response rates were also compared across various subgroups, including age, gender, ISS stage, genetic risk and prior autologous transplant. The clinical data cut-off date for analysis was 30 April 2022. 15 patients in the PD group crossed over to receive PCD treatment; the data up to the date of crossover were considered for the analysis.

Results

Patients

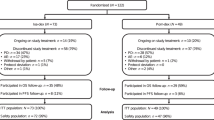

One hundred and twenty-five patients were screened, with one failing the screening. There were 124 patients enrolled between October 2017 and October 2021. Of these patients, 122 received at least one dose of the study drug (62 PCD, 60 PD) and were randomized and included in the mITT analysis. (Fig. 2)

Demographic and baseline characteristics were comparable between treatment arms (Table 1). The median age was 69 (range 47–88) years in the PCD arm and 67 (range 48–85) years in the PD arm. Patients had a median of 3 (range 1–6) prior lines of treatment in both arms. 27 (43.5%) patients in the PCD group and 24 (40.0%) in the PD group had undergone autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) prior to study enrollment. In the PCD arm, 29 of 62 (47%) patients have prior cyclophosphamide exposure. Cyclophosphamide was predominantly used as part of VCD induction. Patients enrolled in our trials were not refractory to cyclophosphamide. When we compared the response rate and PFS of patients with and without prior cyclophosphamide exposure in the PCD arm, there was no difference. (PFS 9.5 months versus 10.9 months, p = 0.19; ORR 54% versus 60%, p = 0.60)

Efficacy

Of the 122 patients, 62 were randomized to PCD and 60 to PD. The median follow-up was 13.5 (inter-quartile range IQR 8.7–24.0) months. The median PFS was 10.9 months (95% CI, 7.1–27.7) in the PCD arm versus 5.8 months (95% CI, 4.4–6.9) in the PD arm. HR for death or progression was 0.43 (95% CI, 0.27–0.69); p < 0.001) for PCD relative to PD (Fig. 3). For responders, the DOR was also significantly longer in PCD (12 months; 95% CI, 7.2 – not estimable [NE]) compared to PD (5.7 months; 95% CI, 3.7–9.7), HR 0.41, 95% CI, 0.20–0.87, p value 0.021 (Fig. 4).

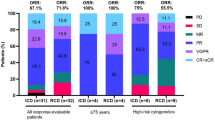

PCD also produced a higher ORR compared to PD. The unadjusted ORR was 61.3% (95% CI, 49.2–73.4) in the PCD arm and 38.3% (95% CI, 26.0–50.6) in the PD arm, with a difference of 23% (95% CI, 5.7–40.2) (Fig. 5). After adjustment for country and ISS stage (I or II versus III), the ORR for PCD was 55.4% (95% CI, 41.0–69.7) and 32% (95% CI, 19.5–44.5) for PD, with difference of 23.3% (95% CI, 6.5–40.2, p-value 0.007). 17.7% of patients in the PCD arm achieved CR or better, compared to PD, where only 3.3% achieved CR or better. There was no statistical difference in OS. The median OS in the PCD arm was 41.5 months (95% CI, 24.5 – NE) and 27.5 months (95% CI, 27.5–NE) in the PD arm. The HR was 0.76 (95% CI, 0.36–1.58) with a p-value of 0.464 (Fig. 6).

The prespecified subgroup analysis for PFS is shown in (Fig. 7). Strata included country, gender, age, ISS stage, genetics, and prior transplant history. The efficacy benefit in PFS provided by PCD over PD was observed across several pre-specified subgroups including older patients > 60 years old, ISS stage III patients, and patients with no prior transplant, with HR of PCD versus PD < 1.

Safety and tolerability

All patients in the mITT analysis (PCD: 62; PD: 60) were included in the safety population. The safety profiles of PCD and PD were generally manageable and tolerable. Overall, 43 (69.4%) patients in the PCD arm and 38 (63.3%) patients in the PD arm had at least one treatment-related adverse event (TEAE) related to study treatment (p = 0.57). There were 38 (61.3%) patients in the PCD arm and 31 (51.7%) patients in the PD arm who experienced any grade 3 and 4 TEAEs (p = 0.36). Notable TEAEs (grade ≥3) reported in ≥10% of subjects in either arm were neutrophil count decreased (PCD: 32.3%; PD: 18.3%, p = 0.097), anemia (PCD: 11.3%; PD: 10.0%, p = >0.99), and pneumonia (PCD: 8.1%; PD: 11.7%, p = 0.56). Gastrointestinal adverse events of any grade were common (PCD: 24.2%, PD: 28.3%, p = 0.68), including diarrhea (PCD: 9.7%, PD: 3.3%, p = 0.27) and constipation (PCD: 8.1%, PD: 15%, p = 0.26). In terms of thrombotic events, deep vein thrombosis was reported by one subject in each study group; pulmonary embolism was reported by two subjects in the PCD group and non in the PD group. Peripheral neuropathy occurred in 9.7% and 3.3% of the PCD and PD groups respectively; of which, 3.2% and 1.7% of patients had grade ≥3 events (p = >0.99).

The percentages of subjects with TEAEs leading to drug reduction, interruption or discontinuation were comparable between the treatment groups. 19 patients (PCD: 8 [12.9%]; PD: 11 [18.3%]) had experienced at least one TEAE leading to drug discontinuation. Dose reduction occurred in 22 (35.6%) patients in the PCD group and 15 (25%) patients in the PD group. The rate of dose modifications for pomalidomide was similar in both arms at 48% of patients (PCD: 30, PD: 29). Common adverse events (AE) are summarized in (Table 2). There were 34 deaths that occurred during the study (PCD: 17, PD: 17). Three deaths were deemed related to study treatment (PCD:1, PD:2); two were from infections, and one from fluid overload.

Discussion

The AMN003 study is the first phase 3 randomized Asian study comparing the efficacy and toxicity of PCD versus PD in subjects with RRMM who have previously been treated with PI and lenalidomide. In this heavily pretreated population with a median of three prior lines of treatment, our study results have shown that PCD significantly prolonged PFS over PD from 5.8 months to 10.9 months (HR for death or progression 0.43; p < 0.001). This was achieved without excess toxicity in the PCD arm.

Although novel therapeutic agents, such as bispecific antibodies, antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies, have shown promising efficacy in RRMM, their widespread application remains limited in many Asian countries due to their high cost and restricted accessibility. Consequently, salvage chemotherapy regimens—such as DCEP (dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, and cisplatin) [10]—and thalidomide-based combinations [11]—such as TCD (thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone) and MPT (melphalan, prednisolone, and thalidomide)—have been utilized as alternative treatment options for RRMM in these regions after failure of bortezomib and lenalidomide. However, these conventional regimens are frequently associated with significant toxicities, including infections and neurotoxicity, which often limited their tolerability and permitted administration for only a limited number of cycles. Therefore, effective regimens based on pomalidomide will be essential for improving the treatment outcomes of RRMM in Asian countries.

Pomalidomide is an important agent that has shown impressive results in salvage treatment options [12] to improve outcomes in heavily pretreated patients. Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating agent that has dose-related effects [13] and well-established immunomodulatory effects in myeloma [14]. Studies have shown that the addition of low-dose cyclophosphamide to an immunomodulatory drug can potentially have a synergistic effect [15, 16], and rescue a proportion of patients previously on PD [17]. This synergistic effect may be one of the reasons behind the positive results in PCD despite dose reductions and modifications based on our study protocol. Cyclophosphamide has also been studied as an addition to PI (like bortezomib) and steroids in other trials, which showed improved efficacy with a good safety profile [18, 19].

Adding a different class of anti-myeloma drug to the PD regimen may increase PFS in patients previously exposed to lenalidomide [20, 21]. PI such as bortezomib [20], carfilzomib [21], and ixazomib [22] or monoclonal antibodies such as elotuzumab [23], daratumumab [24], and isatuximab [25] were previously evaluated to improve the outcomes of the PD regimen. In addition, a humanized antibody–drug conjugate that binds to B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), such as belantamab mafodotin [26] was also investigated to improve the outcomes of the PD regimen. Although these new anti-myeloma drugs improved the outcomes of the PD regimen in RRMM patients, the additional cost and toxicities would be a significant burden, especially in most Asian developing countries. A retrospective cohort study done on healthcare resource utilization and costs in patients with multiple myeloma showed that there was a significant economic burden following double and triple-class-exposed patients [27]. Another study in the US showed that the use of pomalidomide with dexamethasone is associated with similar life-years and quality-adjusted life-years gained compared with daratumumab and carfilzomib, and at a cost less than the other two [28]. In addition, Asian patients are traditionally underrepresented in major international trials, and they possibly have differing treatment tolerability and side effect profiles [29]. Therefore, adding generic oral cyclophosphamide to the PD regimen was an attractive option and was the main background concept for this phase 3 trial.

A comparison with previous studies using triplet regimens provided further insight into the relative efficacy observed in AMN003. A Spanish randomized phase II study [30] comparing KCd (carfilzomib, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone) with Kd (carfilzomib and dexamethasone) did not show statistically significant improvement in PFS with KCd after a median follow-up of 37 months and 1-3 median prior lines of therapy. However, their post hoc analysis observed a significant benefit in PFS of KCd over Kd in the lenalidomide refractory population, which was also the patient population in our study. Taking into consideration the limitations of cross-trial comparisons and overall different study populations, the difference in PFS significance could be due to better synergy of cyclophosphamide with IMiD as compared to PI [14] on top of the difference in phases of clinical trial of the two studies. Our study, compared to the Spanish study, also showed PFS benefit with the addition of cyclophosphamide, despite more median prior lines of therapy of three, indicating that this combination of PCD was able to rescue patients who were refractory after more lines of treatment.

According to outcomes of previously reported PD regimen trials for Asian patients with RRMM, the median PFS was 9.0 months (AMN001 trial) [7], 10.1 months (Japan phase 2 trial) [31], and 5.7 months (China phase 2 trial) [32], respectively. The median PFS of the PCD regimen from previous trials was 6.9 months (elderly patients, Korea) [33] and 13.3 months (US phase 2 trial) [34]. In these previous studies, the benefit of the additional use of oral cyclophosphamide in the PD regimen had not been exactly validated in a prospective trial. To our knowledge, our AMN003 study was the first phase 3 prospective study of pomalidomide combined in a triplet regimen in Asian patients. Although the efficacy and safety of PCD were compared to PD in a previous randomized phase 2 trial, the statistical difference of PFS was not shown (median PFS: 4.4 versus 9.5 months, respectively, p = 0.106) [8]. As our study finally confirmed both efficacy and safety of PCD compared to PD in a phase 3 trial, the PCD regimen should be recommended as the standard 3-drug regimen in a country where new additional target agents are not available for RRMM.

The side effect profile of PCD in our study was comparable to other previously reported studies [6, 31, 35, 36]. Hematological toxicity was the most common adverse event. In another Asian study of PCD treatment in Japan [37], similar to our study, the most frequently occurring grade ≥3 AEs overall were hematological and pneumonia. Our study also concurred with the known relatively low rates of thrombosis in Asians while on immunomodulatory agents [38], despite thromboprophylaxis with aspirin being optional based on physician discretion. Aspirin was not mandated in view of this, as well as the overall lower rates of venous thromboembolism in Asian patients that had been observed [39]. Rates of peripheral neuropathy were higher in PCD compared to PD. Although causes of peripheral neuropathy were commonly thought to be related to the direct mechanism of action of the specific anti-tumoral drug, there could also be off-target effects caused by the addition of cyclophosphamide to the PD regimen, which could potentially cause neuroinflammation and altered neuronal excitability caused by other pro-inflammatory cytokines [40].

There were some limitations to our study. Information on high-risk genetic was not routinely collected by participating sites when patients were diagnosed, and it was not routine to collect genetic information at relapse, and this was also not mandated by the study. However, the randomized nature of the study should ensure the percentage of patients with high-risk genetic to be relatively even on both arms. In addition, we lacked minimal residual disease (MRD) data as our study was done before MRD was recommended as an endpoint in 2024. Furthermore, in these heavily pre-treated patients and with the drugs being studied, it is unlikely that there will be many who will achieve MRD-negative response.

Conclusion

The prognosis of patients with RRMM is dismal. Repeat accessibility to novel agents is limited outside the US. Our trial shows that combining a 3rd generation immunomodulatory agent like pomalidomide with conventional treatment in a triplet combination improved PFS over a doublet without a significant increase in rate of AE. Thus, PCD treatment represents a feasible and cost-effective treatment option in this group of Asian patients with RRMM, and can be considered to be the standard pomalidomide-containing regimen in this group of patients.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111:2962–72.

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Laversanne M, Colombet M, Mery L, et al. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer 2024 [Available from: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/900-world-fact-sheet.pdf.

Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Gertz MA, Buadi FK, Pandey S, et al. Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma: changes in early mortality and outcomes in older patients. Leukemia. 2014;28:1122.

Kastritis E, Terpos E, Dimopoulos MA. How I treat relapsed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2022;139:2904–17.

Kumar SK, Lee JH, Lahuerta JJ, Morgan G, Richardson PG, Crowley J, et al. Risk of progression and survival in multiple myeloma relapsing after therapy with IMiDs and bortezomib: A multicenter international myeloma working group study. Leukemia. 2012;26:149–57.

Miguel JS, Weisel K, Moreau P, Lacy M, Song K, Delforge M, et al. Pomalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone versus high-dose dexamethasone alone for patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (MM-003): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1055–66.

Soekojo CY, Kim K, Huang S-Y, Chim C-S, Takezako N, Asaoku H, et al. Pomalidomide and dexamethasone combination with additional cyclophosphamide in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (AMN001)—a trial by the Asian Myeloma Network. Blood Cancer J. 2019;9:83.

Baz RC, Martin TG, Lin H-Y, Zhao X, Shain KH, Cho HJ, et al. Randomized multicenter phase 2 study of pomalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone in relapsed refractory myeloma. Blood. 2016;127:2561–8.

Group IMW. International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) Uniform Response Criteria for Multiple Myeloma 2024 [Available from: https://www.myeloma.org/resource-library/international-myeloma-working-group-imwg-uniform-response-criteria-multiple.

Park S, Lee SJ, Jung CW, Jang JH, Kim SJ, Kim WS, et al. DCEP for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma after therapy with novel agents. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:99–105.

Jung KS, Kim K, Kim HJ, Kim SH, Lee J-O, Kim JS, et al. Analysis of the efficacy of thalidomide plus dexamethasone-based regimens in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who received prior chemotherapy, including Bortezomib and Lenalidomide: KMM-166 Study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20:e97–e104.

McCurdy AR, Lacy MQ. Pomalidomide and its clinical potential for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: an update for the hematologist. Ther Adv Hematol. 2013;4:211–6.

Ogino MH, Tadi P. Cyclophosphamide. StatPearls [Internet]: StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

Swan D, Gurney M, Krawczyk J, Ryan AE, O’Dwyer M. Beyond DNA Damage: Exploring the immunomodulatory effects of cyclophosphamide in multiple myeloma. HemaSphere. 2020;4:e350.

Garderet L, Kuhnowski F, Berge B, Roussel M, Escoffre-Barbe M, Lafon I, et al. Pomalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2018;132:2555–63.

Nijhof IS, Franssen LE, Levin M-D, Bos GMJ, Broijl A, Klein SK, et al. Phase 1/2 study of lenalidomide combined with low-dose cyclophosphamide and prednisone in lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2016;128:2297–306.

Weisel KC, Scheid C, Zago M, Besemer B, Mai EK, Haenel M, et al. Addition of cyclophosphamide on insufficient response to pomalidomide and dexamethasone: results of the phase II PERSPECTIVE Multiple Myeloma trial. Blood cancer J (N. Y). 2019;9:45.

Kropff M, Vogel M, Bisping G, Schlag R, Weide R, Knauf W, et al. Bortezomib and low-dose dexamethasone with or without continuous low-dose oral cyclophosphamide for primary refractory or relapsed multiple myeloma: a randomized phase III study. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:1857–66.

de Waal EGM, de Munck L, Hoogendoorn M, Woolthuis G, van der Velden A, Tromp Y, et al. Combination therapy with bortezomib, continuous low-dose cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone followed by one year of maintenance treatment for relapsed multiple myeloma patients. Br J Haematol. 2015;171:720–5.

Richardson PaulG, Oriol Albert, Beksac Meral, Anna, Liberati Marina, Galli Monica, et al. Pomalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma previously treated with lenalidomide (OPTIMISMM): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:781–94. 2019

Sonneveld P, Zweegman S, Cavo M, Nasserinejad K, Broijl A, Troia R, et al. Carfilzomib, Pomalidomide, and Dexamethasone as second-line therapy for lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma. HemaSphere. 2022;6:e786.

Bobin A, Manier S, De Keizer J, Srimani JK, Hulin C, Karlin L, et al. Ixazomib, pomalidomide and dexamethasone in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma characterized with high-risk cytogenetics: the IFM 2014-01 study. Haematologica. 2024.

Dimopoulos MA, Dytfeld D, Grosicki S, Moreau P, Takezako N, Hori M, et al. Elotuzumab plus Pomalidomide and Dexamethasone for Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl J Med. 2018;379:1811–22.

Dimopoulos MA, Terpos E, Boccadoro M, Delimpasi S, Beksac M, Katodritou E, et al. Daratumumab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone versus pomalidomide and dexamethasone alone in previously treated multiple myeloma (APOLLO): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:801–12.

Attal M, Richardson PG, Rajkumar SV, San-Miguel J, Beksac M, Spicka I, et al. Isatuximab plus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone versus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (ICARIA-MM): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394:2096–107.

Dimopoulos M, Hungria V, Radinoff A, Delimpasi S, Mikala G, Masszi T, et al. Efficacy and safety of single-agent belantamab mafodotin versus pomalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (DREAMM-3): a phase 3, open-label, randomised study. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10:e801–e12.

Yang JS Healthcare Resource Utilization and Costs among Multiple Myeloma Patients with Double- or Triple-Class Exposure: A Retrospective U.S. Claims Database Analysis [Master’s]. United States -- Washington: University of Washington; 2022.

Pelligra CG, Parikh K, Guo S, Chandler C, Mouro J, Abouzaid S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Pomalidomide, Carfilzomib, and Daratumumab for the treatment of patients with heavily pretreated relapsed–refractory multiple myeloma in the United States. Clin Ther. 2017;39:1986–2005.e5.

Tan D, Chng WJ, Chou T, Nawarawong W, Hwang S-Y, Chim CS, et al. Management of multiple myeloma in Asia: resource-stratified guidelines. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e571–81.

Puertas B, González-Calle V, Sureda A, Moreno MJ, Oriol A, González E, et al. Randomized phase II study of weekly carfilzomib 70 mg/m2 and dexamethasone with or without cyclophosphamide in relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma patients. Haematologica. 2023;108:2753–63.

Ichinohe T, Kuroda Y, Okamoto S, Matsue K, Iida S, Sunami K, et al. A multicenter phase 2 study of pomalidomide plus dexamethasone in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: the Japanese MM-011 trial. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2015;5.

Fu W-J, Wang Y-F, Zhao H-G, Niu T, Fang B-J, Liao A-J, et al. Efficacy and safety of pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone in Chinese patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: a multicenter, prospective, single-arm, phase 2 trial. BMC Cancer. 2022;22.

Lee HS, Kim K, Kim SJ, Lee JJ, Kim I, Kim JS, et al. Pomalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone for elderly patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: A study of the Korean Multiple Myeloma Working Party (KMMWP-164 study). Am J Hematol. 2020;95:413–21.

Van Oekelen O, Parekh S, Cho HJ, Vishnuvardhan N, Madduri D, Richter J, et al. A phase II study of pomalidomide, daily oral cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61:2208–15.

Garderet L, Polge E, Kellil C, Ova JGO, Beohou E, Labopin M, et al. Pomalidomide, Cyclophosphamide and Dexamethasone for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: a retrospective single center experience. Blood. 2015;126:1858.

Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Corradini P, Cavo M, Delforge M, Di Raimondo F, et al. Safety and efficacy of pomalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone in STRATUS (MM-010): a phase 3b study in refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2016;128:497–503.

Matsue K, Iwasaki H, Chou T, Tobinai K, Sunami K, Ogawa Y, et al. Pomalidomide alone or in combination with dexamethasone in Japanese patients with refractory or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:1561–7.

Koh Y, Bang S-M, Lee JH, Yoon H-J, Do Y-R, Ryoo H-M, et al. Low incidence of clinically apparent thromboembolism in Korean patients with multiple myeloma treated with thalidomide. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:201–6.

Nicole Tran H, Klatsky AL. Lower risk of venous thromboembolism in multiple Asian ethnic groups. Prev Med Rep. 2019;13:268–9.

Was H, Borkowska A, Bagues A, Tu L, Liu JYH, Lu Z, et al. Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity. Front Pharm. 2022;13:2022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WJC and BGMD conceived and designed the study. XL, NA, YP, WJC collected and assembled the data. JSK, CSC, JJL, SSY, SCN, GGG, HH, JHL, KL, SI, JSYH, CKM, OGMM, SDM, CS, WJC recruited the patients. JSK, YS, WYJ, NA, YP, WJC analyzed and interpreted the data. JSK, YS, WYJ, WJC wrote the manuscript. All authors provided final approval for the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no relevant conflict of interest. The study drug pomalidomide is provided by BMS who also provided some research funding for the study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed in compliance with the requirements of the local regulatory authorities in Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia, and Japan, and was conducted in accordance with the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) regulations. The study was approved by the Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB) in Singapore (DSRB reference 2017/00228) and the respective IRB of participating countries. Written informed consent in accordance with federal, local, and institutional guidelines was obtained from all subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J.S., Song, Y., Jen, WY. et al. Randomized Phase 3 study of pomalidomide cyclophosphamide dexamethasone versus pomalidomide dexamethasone in relapse or refractory myeloma: an Asian Myeloma Network study (AMN003). Blood Cancer J. 15, 155 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01356-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01356-z