Abstract

Allogeneic stem cell transplant (ASCT) remains the only curative option in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML). We retrospectively analyzed 138 CMML patients who underwent ASCT at the Mayo Clinic. Patients who transitioned to ASCT while in chronic phase (Group A) displayed superior post-transplant survival (PTS), compared to those in whom ASCT was performed after blast transformation (BT; Group B) (median 95 vs. 16 months; p = 0.01). In Group A, PTS was superior in patients with <5% bone marrow (BM) blasts at time of ASCT (median 164 vs. 13.5 months; p = 0.01). Other predictors of superior PTS included day-100 BM blast <5% or normal cytogenetics (median 164 vs. 18 months; p = 0.01) or presence of chronic graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD; median 164 vs. 26 months; p = 0.01). Pre-ASCT hypomethylating agent exposure (HR = 2.03; p = 0.03), and receiving more than one line of pre-ASCT chemotherapy (p = 0.01) predicted inferior PTS. In multivariable analysis, predictors of superior GVHD-free and relapse-free survival (GRFS) included the use of myeloablative conditioning and the absence of morphologically or cytogenetically apparent disease at day-100. The use of post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy) was associated with a higher cumulative incidence of relapse (p = 0.02) and numerically inferior PTS (p = 0.1). Group B patients also appeared to benefit from achieving BM blast <5% at the time of ASCT (p = 0.4) as well as at day-100 (p = 0.01), in terms of PTS, while full chimerism and normal cytogenetics at day-100 were associated with superior GRFS. These observations support the value of ASCT in CMML, especially if performed prior to BT and in the presence of <5% BM blasts at the time of ASCT. Additionally, the observed detrimental impact of PTCy requires additional studies to confirm and investigate the underlying mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

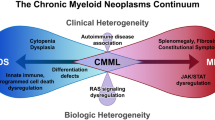

Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) is a clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorder characterized by persistent monocytosis in the peripheral blood and features overlapping those of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) [1,2,3]. The clinical course of CMML is heterogenous, with a recognized risk of progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), referred to as blast transformation (BT) [4, 5]. BT occurs in 15-30% of cases and is associated with poor prognosis, with a report of median overall survival (OS) as short as 6 months following transformation, and a 5-year survival rate of only about 6% [5,6,7,8].

Conventional therapies, including hydroxyurea and hypomethylating agents (HMA), may provide symptomatic benefits but are not curative [9]. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (ASCT) remains the only potentially curative treatment option [10, 11]. While the long-term benefits of ASCT in selected patients are well recognized, the risk of transplant-related complications and non-relapse mortality makes patient selection critical [12]. Typically, younger patients have shown better outcomes [12]; however, this presents a challenge in CMML patients as the median age at diagnosis is between 70 and 74 years [13, 14].

In our previous study (N = 70), we demonstrated a survival benefit from ASCT, particularly when performed in chronic phase disease, compared to undergoing ASCT after BT (5-year OS of 51% vs. 19%) [11]. The same study also showed that the median graft versus host disease (GVHD)-free relapse-free survival (GRFS) was only 7 months, underscoring both the benefit and morbidity associated with ASCT. The median age in this study, as in most other ASCT studies, was 58 years [11, 15, 16]. In the particular study, only an abnormal karyotype was adversely prognostic [11]. Gagelmann et al. found that an ASXL1 and/or NRAS-mutated genotype, bone marrow (BM) blasts >2%, and high hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index (HCT-CI) were independently predictive of worse post-transplant survival (PTS) [16].

Reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens and alternative donor sources such as haploidentical and umbilical cord blood donors have expanded ASCT eligibility to a broader patient population [17,18,19,20]. Despite these advances, the decision to proceed with ASCT in CMML remains challenging. Compared with myeloablative conditioning (MAC) regimen, RIC offers the benefit of lower non-relapse mortality, but it may be associated with a higher rate of relapse [21]. However, some CMML studies reported no differences in OS between MAC and RIC [12, 21]. Implementation of post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy) has improved the GRFS in phase III trials [22, 23]. However, recent reports observed a tendency toward increased risk of relapse with the use of PTCy [24].

There is a lack of prospective data analyzing these risk factors to guide patient selection. In addition, CMML-specific retrospective studies are few, and significant gaps still exist in our understanding of the prognostic impact of various clinical, cytogenetic, molecular risk factors and choice of conditioning regimen in the setting of ASCT for CMML. The aim of the current study was to evaluate PTS and identify risk factors influencing transplant outcomes in CMML patients who underwent ASCT.

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted under a Mayo Clinic IRB-approved minimal risk protocol (Mayo Clinic—IRB:12-003574). We identified patients with CMML who underwent ASCT between 1995 and 2024 using the Mayo Clinic electronic databases, which included patients from Mayo Clinic Rochester, Florida, and Arizona, USA. Clinical, laboratory, and outcome data were extracted from these databases. CMML diagnosis and categorization (CMML-1/CMML-2) and myelodysplastic(MD-CMML)/myeloproliferative(MP-CMML) subtypes were made according to the International Consensus Classification (ICC) and confirmed by central review [1]. Mutations/variants in genes associated with myeloid neoplasms were screened by next-generation sequencing in accordance with institutional protocols for clinical use. Cytogenetic findings were reported using the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature [25].

CMML patients were classified into two groups based on the timing of blast transformation. Group A included patients who underwent ASCT while in chronic phase CMML, while Group B included those who had ASCT following BT. Promonocytes were included in the blasts count. Risk stratification was performed using the updated CMML-specific prognostic scoring system that includes molecular abnormalities (CPSS-mol) and BLAST scores, as defined by Elena et al. and Tefferi et al., respectively [26, 27]. The BLAST score uses a point-based system, and it includes circulating blasts ≥ 2% (1 point), leukocytes ≥ 13 × 10⁹/L (1 point), and severe (2 points) or moderate (1 point) anemia. Based on the total score, patients were stratified into low-risk (0 points), intermediate-risk (1 point), and high-risk (2–4 points) [27]. HCT-CI and Karnofsky performance status (KPS) scores were calculated as described by Sorror et al. and Karnofsky et al., respectively [28, 29].

Platelet engraftment was defined as the first of three consecutive days with a platelet count of ≥20,000/μL in the absence of platelet transfusion for seven consecutive days [30]. Neutrophil engraftment was defined as the first of 3 successive days with an absolute neutrophil count ≥500/μL after the post-transplantation nadir [30]. Donor chimerism was classified according to the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) criteria: full donor chimerism if myeloid and lymphoid lineages were >95%, mixed or partial chimerism if 5–95%, and lost/absent donor chimerism if <5% [30].

PTS was measured from the date of ASCT to death from any cause. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time from ASCT to relapse or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. GRFS was defined as the time from ASCT to grade 3–4 acute GVHD (aGVHD), systemic therapy-requiring chronic GVHD (cGVHD), relapse, or death, whichever occurred first [31]. Non-relapse mortality (NRM) was defined as the time from ASCT to death from any cause without a prior relapse or progression. Cumulative incidence of relapse and NRM were estimated using the cumulative incidence method for competing risks. Death and relapse were considered competing risks for relapse and NRM, respectively. Median follow-up was calculated using the reverse Kaplan–Meier method.

Frequencies and percentages were used to summarize categorical variables, while medians and ranges were used for quantitative variables. Time-to-event analyses were performed using Kaplan–Meier estimates, intergroup comparisons assessed with the log-rank test and hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression. Multivariable analyses (MVA) to identify the impact of risk factors were performed using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP Pro 18.0.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Presenting clinical and laboratory characteristics

A total of 138 Mayo Clinic patients (62% male) with CMML who underwent ASCT were included in the study (Table 1). The median ages at the time of diagnosis and at the time of ASCT were 62 (range 18–75) and 63 (range 18–76) years, respectively. Group A comprised 104 patients, while Group B consisted of 34 patients. All patients underwent transplantation between 1995 and 2024. At initial diagnosis, CMML-1/CMML-2 and MD-CMML/MP-CMML phenotypes were seen in 78%/22% and 54%/46% of patients, respectively. Among patients with available molecular data (n = 86), the most frequent mutations/variants were ASXL1 (56%), TET2 (44%), and SRSF2 (38%). Abnormal karyotypes were observed in 31% of patients. CPSS-Mol risk categories at diagnosis were low (17%), intermediate-1 (11%), intermediate-2 (40%), and high (32%). BLAST score categories were low risk (38%), intermediate risk (44%), and high risk (18%). Compared to Group B, patients in Group A were more likely to present with RUNX1 mutations/variants (24% vs. 0%; p = 0.01) and more often received pre-transplant HMA (64% vs. 36%; p = 0.01). In contrast, Group B patients more frequently received intensive chemotherapy prior to ASCT (79% vs. 13%; p = 0.01). Other clinical and laboratory characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Pre- and peri-transplant treatment and disease status

HMAs were used as first-line CMML-directed therapy in 75 (60%) patients, intensive chemotherapy in 29 (23%), other therapies (including hydroxyurea, erythropoietin agonist, danazol, ruxolitinib, or clinical trials) in 16 (13%), and no treatment in 5 (4%; Table 1). Twenty-nine (21%) patients received two or more lines of cytotoxic therapies.

Bone marrow assessment at the time of ASCT was available in 126 (91%) patients. In Group A, BM blasts were <5% in 76 (80%), 5–9% in 15 (16%) and 10–19% in 4 (4%) patients. In Group B, BM blasts were <5% in 26 (85%), 5–9% in 2 (6%) and 10–19% in 2 (6%; Table 2) patients. Among patients with BM blasts <5%, abnormal cytogenetics were observed in 20 (30%) patients in Group A and 6 (30%) in Group B. Median KPS score prior to transplant was 90 in both Group A (range: 50–100) and Group B (range: 70–100). HCT-CI scores were 0–1 in 42%, 2–3 in 41%, and ≥4 in 16% of patients.

Donor types included matched unrelated (MUD; 58%), matched sibling (MSD; 25%), mismatched unrelated (MMUD; 7%), haploidentical (Hapolo; 9%), and cord blood (1%). RIC was used in 99 patients (73%) and MAC in 36 (26%). Specifically, 17 (13%) patients received busulfan-based MAC, 15 (12%) received cyclophosphamide with total body irradiation (Cy-TBI) MAC, 21 (16%) received busulfan-based RIC, 64 (49%) received melphalan-based RIC, 9 (7%) received Fludarabine-Cy-TBI based RIC (Flu/Cy/TBI), and 4 (3%) received other regimens. GVHD prophylaxis was methotrexate-based in 84 patients (64%) and PTCy-based in 39 (30%). The median donor age was 30 years (range 13–73), and 57% of donors were male (Table 2). Among the 39 patients who received PTCy, 21 (54%) patients received stem cells from MUD, 12 (30%) from Haplo, 5 (13%) from MMUD and 1 (3%) from MSD. In the same group, RIC was used in 35 (90%) and MAC in 4 (10%) patients.

Post-transplant survival and risk factors

Among 138 patients, 68 (49%) had died at the time of censoring. The median follow-up duration was 71 months (range, 3–212). The median time from diagnosis to ASCT was 11 months (range: 0–201). The median OS from the time of initial diagnosis was 67 months (range, 8–239), and the median PTS was 54 months (range: 0–212), with 1-, 3-, and 5-year PTS rates of 74%, 57%, and 48%, respectively (supplementary Table 1). The median RFS was 34 months, with 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates of 66%, 49%, and 42%, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). Group B patients had significantly worse PTS compared with those in group A (16 vs. 95 months; P = 0.01; HR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2–3.2; Fig. 1).

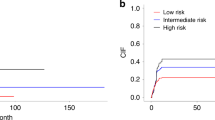

In group A, the median PTS was 95 months (range, 0–212), with 1-, 3-, and 5-year PTS rates of 79%, 62%, and 54%, respectively. The median RFS was 54 months, with 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates of 71%, 52%, and 46%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1). In univariate survival analysis (UVA), BM blasts at the time of ASCT of <5%, 5–9%, and 10-19% were associated with median OS of 164, 69 (HR 1.8), and 13.5 (HR 4.3) months, respectively (p = 0.01, Fig. 2A).

Kaplan–Meier curves illustrate post-transplant survival of CMML patients stratified by bone marrow blast percentage at time of transplant in patients who underwent ASCT (A) in chronic phase CMML and B after experiencing blast transformation. C Post-transplant survival stratified by cytogenetics at time of CMML diagnosis in patients who underwent ASCT in chronic phase CMML. Patients who had bone marrow blasts less than 5% at the time of transplant and normal cytogenetics at initial diagnosis demonstrated better post-transplant survival.

Group A Patients who received two or more lines of cytotoxic therapies had inferior PTS (median 11 months) compared to those treated with one line (69 months; HR 3.6) or those who did not receive any cytotoxic drugs (95 months; HR 4.6; p = 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 2a). Additional factors associated with inferior PTS included abnormal cytogenetics at diagnosis (p = 0.02; HR 1.9, 95% CI 1.06–3.6; Fig. 2C), and pre-ASCT exposure to HMA (p = 0.03; HR 2.03, 95% CI 1.02–4; Fig. 3A).

Kaplan–Meier curves illustrate post-transplant survival of CMML patients stratified by history of pre-transplant HMA exposure in patients who underwent ASCT (A) in chronic phase CMML and B after experiencing blast transformation. Pre-transplant HMA exposure correlated with inferior post-transplant survival.

PTS was longest in Group A patients who received busulfan-based MAC and shortest in those who received Flu/Cy/TBI-based conditioning (median not reached vs. 22 months; p = 0.2; Supplementary Fig. 3a). Compared to other GVHD prophylaxis strategies, PTCy was associated with a shorter median PTS (22 vs. 107 months; p = 0.1; Fig. 4A) and significantly higher cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR; p = 0.02; Fig. 4B). In subgroup analysis accounting for donor type and conditioning intensity, similar findings of higher CIR with PTCy were observed in HLA-matched, including MSD and MUD, RIC recipient (p = 0.02; Supplementary Fig. 4). Further subgroup analysis in HLA-mismatched or MAC recipient was less informative due to the small number of patients. Group A patients who were in complete morphologic remission (CR) at day100 post-ASCT had better PTS (median 164 vs. 18 months; p = 0.01, HR 0.2, 95% CI: 0.1–0.5; Fig. 5A). PTS was worse in patients with aGVHD grade 2-4 compared to those with grade ≤1 aGVHD (median 21 vs. 164 months; p = 0.01; HR 2.6, 95% CI: 1.4–4.9; Fig. 6A). Chronic GVHD of any grade confers better PTS (median 164 vs. 26 months; p = 0.01; HR 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1–0.6; Fig. 6B). We found no association between donor type, age, gender and PTS.

A Kaplan–Meier curve illustrates numerically inferior post-transplant overall survival of CMML patients who received post-transplant cyclophosphamide. B Cumulative Incidence Curve illustrates higher cumulative incidence of relapse using death as a competing risk in CMML patients who received post-transplant cyclophosphamide.

Kaplan–Meier curves illustrate post-transplant survival of CMML patients stratified by bone marrow morphology on day 100 post-ASCT in patients who underwent ASCT (A) in chronic phase CMML and B after experiencing blast transformation. C Post-transplant survival stratified by cytogenetics on day 100 post-ASCT in patients who underwent ASCT in chronic phase CMML. Longer post-transplant overall survival was observed in patients who were in morphologic remission and in patients who had normal cytogenetics at day 100 post-transplant.

Multivariable Cox regression model including BM blasts at the time of ASCT and at day-100 post-ASCT, number chemotherapeutic lines before transplant, cytogenetics at diagnosis and day-100 post-ASCT, pre-ASCT exposure to HMA, conditioning regimen, GVHD prophylaxis, acute GVHD and chronic GVHD identified abnormal cytogenetics at day 100 (p = 0.01, HR 5.4, 95% CI: 2.1–13) and aGVHD grade 2–4 (p = 0.01, HR 3.6, 95% CI: 1.5–8) to be independently associated with inferior PTS. Conversely, BM blasts <5% at the time of ASCT (p = 0.03, HR 0.4, 95% CI: 0.1–0.9) and at day-100 post-ASCT (p = 0.08, HR 0.3, 95% CI: 0.8–1.1), and chronic GVHD of any grade (p = 0.01, HR 0.2, 95% CI: 0.1–0.5) were independently associated with improved PTS in group A patients.

In group B, median PTS was 16 months (range 0–204), with a 1-, 3- and 5-year PTS rates of 57%, 39% and 29%, respectively. The RFS was 10 months, with a 1-, 3- and 5-year RFS rates of 49%, 38% and 29%, respectively. In univariate analysis, relapse at day-100 post ASCT correlated with worse PTS (median 11 vs. 39 months; p = 0.01, HR 5.3, 95% CI 1.4–20; Fig. 5B). PTS was longer with BM blasts of <5% compared to BM blasts ≥5% at the time of ASCT (median 30 vs. 18 months), although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.4; Fig. 2B). In group B patients, cGVHD of any grade led to a better PTS (30 vs. 18 months; p = 0.5). In multivariable analysis, BM blasts at day-100 post-ASCT (p = 0.01, HR 0.09, 95% CI 0.01–0.4) were independently associated with better PTS.

At the last follow-up, 46 patients (44%) in group A and 22 (64%) in group B were dead. The causes of death were relapse/non-relapse related in 36/64% in group A and 39/61% in group B, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The most frequent documented causes of non-relapse mortality were GVHD in 12 (30%) patients, infections in 9 (23%), bleeding in 4 (10%) and solid organ malignancy in 4 (10%). There was a trend towards improved PTS between patients who were transplanted after 2010 compared to those who were transplanted before 2010 in both group A (median 107 vs. 81 months, p = 0.6) and group B (median 18 vs. 8 months, p = 0.2), respectively.

Graft-versus-host disease and graft-versus-host disease-free, relapse-free survival

Grade ≥2 aGVHD and moderate to severe cGVHD occurred in 44% and 30% of Group A patients and in 47% and 26% of Group B patients, respectively. Skin was the most frequently involved organ in aGVHD, occurring in 60 (43%) patients, followed by the gut in 44 (32%) and the liver in 18 (13%). Similarly, for cGVHD, skin was most frequently involved, occurring in 31 (22%) patients, followed by ocular and oral in 20 (20% each), lung in 22 (16%), liver in 20 (15%), and gut in 10 (7%).

In Group A, the median GRFS was 239 days, with 1-, 3-, and 5-year GRFS rates of 41%, 21%, and 16%, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). MAC was associated with significantly better GRFS compared to RIC (median 622 vs. 206 days; p = 0.02, HR 2.1, 95% CI: 1.2–3.7; Supplementary Fig. 5a). In contrast, abnormal cytogenetics (median 130 vs. 282 days; p = 0.01, HR 2.6, 95% CI: 1.3–5.4; Supplementary Fig. 5c) and BM blasts of ≥5% at day-100 post-ASCT (median 94 vs. 245 days; p = 0.01, HR 4.3, 95% CI: 1.5–12.0, Supplementary Fig. 5e) were significantly associated with shorter GRFS. All these variables remained statistically significant in multivariable analysis (p = 0.01 in all instances).

In Group B, the median GRFS was 169 days, with 1-, 3-, and 5-year GRFS rates of 30%, 16%, and 16%, respectively. Mixed chimerism at day 100 post-ASCT was associated with significantly shorter GRFS compared to full donor chimerism (median 97 vs. 195 days; p = 0.01, HR 5.3, 95% CI: 1.3–22.0). Similarly, BM blasts of ≥5% at day-100 demonstrated a trend toward inferior GRFS (97 vs. 195 days; p = 0.05, HR 2.8, 95% CI: 0.9–8.9; Supplementary Fig. 5f).

Discussion

The natural history of CMML is characterized by disease progression and eventual BT, with ASCT considered the only potentially curative therapy. [3, 5, 8]. In existing retrospective studies, post-transplant outcomes are influenced by HCT-CI, abnormal karyotype, ASXL1 and NRAS mutation, BM blasts and remission status pre-ASCT [11, 16]. In this study, we assessed the impact of baseline characteristics, peri-transplant disease status, day-100 assessment, choice of conditioning regimen, as well as occurrence of GVHD on PTS.

We reported a median PTS of 95 and 16 months with 3-/5-year PTS rates of 62/54% and 39/29% in groups A and B, respectively. These outcomes are consistent with findings from the previous Mayo Clinic study [11] and the 3- and 5-year PTS rates of 55% and 50% reported by Gagelmann et al. [10]. Similar to earlier reports, PTS was better in patients who had ASCT while in chronic phase, supporting the consideration of early transplant [11, 32]. On the other hand, a large retrospective study including 1114 CMML patients has shown shorter PTS in lower risk CMML and no PTS benefit in higher risk CMML patients in comparison to those who did not undergo ASCT [12]. These discrepancies highlight the need for prospective studies to better define the optimal timing of ASCT. Nonetheless, our findings support considering ASCT before BT, particularly in high-risk patients, a group in which the benefits of transplantation have been consistently reported [10,11,12, 33, 34].

The BM blast percentages, both at the time of ASCT and at day-100 post-ASCT, were independently associated with better PTS. This aligns with findings from Symeonidis et al, in a study of 513 patients with CMML in the EBMT database, where achievement of CR, and by inference lower blast percentage, were associated with better PTS [32]. Similarly, in a proposed CMML transplant scoring system, BM blasts >2% were found to be independently and adversely prognostic and assigned the highest point value [16]. These studies, along with our previous study and the newly proposed BLAST score (circulating blast) [27] demonstrate the dynamic prognostic significance of blast quantity at different stage of CMML and could guide choice of treatment strategies.

However, in patients who already experienced BT before transplant, the difference in PTS between those with BM blasts at the time of ASCT of <5% (30 months) and those with BM blasts of ≥5% (18 months) did not reach statistical significance. Although ASCT remains a key part of the treatment of CMML patients who had BT, the outcome following BT is grim [6] and our study only found PTS benefits and better GRFS in patients who achieved CR at day-100 post-ASCT. Full donor chimerism at day-100 also offers better GFRS but no impact on PTS in this cohort.

The busulfan-based MAC regimen was associated with favorable PTS and GRFS in CMML patients who underwent transplant prior to BT. Some studies have reported similar trends, while other studies reported no significant difference [12, 35,36,37,38]. Given the dual benefit of improved PTS and better GRFS reported in this study, MAC may be a preferred option over RIC when clinically feasible. PTCy has emerged as a new standard of care in ASCT practice based on large randomized clinical trials' results demonstrating better GRFS [22, 23]. This has resulted in increased implementation of PTCy in the current study cohort, as 56% of the ASCT procedures performed between 2020 and 2024 have utilized PTCy for GVHD prophylaxis. However, in our study, PTCy correlated with higher cumulative incidence of relapse and numerically, although not statistically significant, shorter PTS, which aligns with the results from recently reported real-world experiences [24, 39]. In addition, normal cytogenetics at day-100 post-ASCT, grade 0–1 aGVHD (compared with ≥2) and any grade of cGVHD were associated with improved outcomes. These findings are consistent with those reported in a cohort of 177 CMML patients from three HSCT registries in Japan [40]. Notably, we found no association between donor type, age and gender. Exposure to HMA before ASCT and receiving two or more lines of chemotherapies were only significant on UVA and not MVA, suggesting they may not be an independent predictor of PTS. A study by Schroeder et al. compared upfront ASCT vs pre-ASCT cytoreductive bridging therapy in high-risk MDS, including CMML and secondary AML, proposed the possibility of resistant clone selection with pre-ASCT cytoreduction therapy [41].

We acknowledge that our study is subject to limitations inherent to retrospective analyses, including but not limited to missing data, heterogeneity arising from data collected across multiple centers, limited post-ASCT molecular profiling data, and the long duration over which the data were collected. Moreover, the small numbers of group B patients and PTCy recipients might limit the generalizability of our findings. Additional studies are needed to confirm these findings. In summary, this study suggests that ASCT offers survival benefits in CMML patients, especially if done before BT. We highlighted the prognostic impact of BM blast percentages at the time of ASCT and at Day-100 post-ASCT, with better PTS observed in patients with <5% BM blasts. MAC regimen and occurrence of Chronic GVHD were also associated with better PTS, while abnormal cytogenetics at day-100 post-ASCT and aGVHD predict inferior PTS. The use of PTCy conferred a higher incidence of relapse. These insights can inform risk-adapted transplant strategies and underscore the need for prospective studies to refine patient selection criteria and guide transplant timing.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to Mayo Clinic patients’ confidentiality, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian RP, Borowitz MJ, Calvo KR, Kvasnicka H-M, et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood. 2022;140:1200–28.

Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, Akkari Y, Alaggio R, Apperley JF, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36:1703–19.

Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2024;99:1142–65.

Bangolo A, Amoozgar B, Thapa A, Bajwa W, Nagesh VK, Nyzhnyk Y, et al. Survival outcomes of U.S. patients with CMML: a two-decade analysis from the SEER database. Med Sci (Basel). 2024;12:60.

Pleyer L, Leisch M, Kourakli A, Padron E, Maciejewski JP, Xicoy Cirici B, et al. Outcomes of patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia treated with non-curative therapies: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e135–e48.

Patnaik MM, Pierola AA, Vallapureddy R, Yalniz FF, Kadia TM, Jabbour EJ, et al. Blast phase chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: Mayo-MDACC collaborative study of 171 cases. Leukemia. 2018;32:2512–8.

Rivera Duarte A, Armengol Alonso A, Sandoval Cartagena E, Tuna Aguilar E. Blastic transformation in Mexican population with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17:532–8.

Such E, Germing U, Malcovati L, Cervera J, Kuendgen A, Della Porta MG, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic scoring system for patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2013;121:3005–15.

Itzykson R, Santini V, Thepot S, Ades L, Chaffaut C, Giagounidis A, et al. Decitabine versus hydroxyurea for advanced proliferative chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: results of a randomized phase III trial within the EMSCO network. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:1888–97.

Gagelmann N, Bogdanov R, Stölzel F, Rautenberg C, Panagiota V, Becker H, et al. Long-term survival benefit after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Transplant Cell Ther. 2021;27:95.e1–e4.

Pophali P, Matin A, Mangaonkar AA, Carr R, Binder M, Al-Kali A, et al. Prognostic impact and timing considerations for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10:121.

Robin M, de Wreede LC, Padron E, Bakunina K, Fenaux P, Koster L, et al. Role of allogeneic transplantation in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: an international collaborative analysis. Blood. 2022;140:1408–18.

Padron E, Garcia-Manero G, Patnaik MM, Itzykson R, Lasho T, Nazha A, et al. An international data set for CMML validates prognostic scoring systems and demonstrates a need for novel prognostication strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5:e333–e.

Itzykson R, Kosmider O, Renneville A, Gelsi-Boyer V, Meggendorfer M, Morabito M, et al. Prognostic score including gene mutations in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2428–36.

Robin M, Itzykson R. Contemporary treatment approaches to CMML—is allogeneic HCT the only cure? Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2020;33:101138.

Gagelmann N, Badbaran A, Beelen DW, Salit RB, Stölzel F, Rautenberg C, et al. A prognostic score including mutation profile and clinical features for patients with CMML undergoing stem cell transplantation. Blood Adv. 2021;5:1760–9.

Kekre N, Antin JH. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation donor sources in the 21st century: choosing the ideal donor when a perfect match does not exist. Blood. 2014;124:334–43.

Schetelig J, de Wreede LC, van Gelder M, Koster L, Finke J, Niederwieser D, et al. Late treatment-related mortality versus competing causes of death after allogeneic transplantation for myelodysplastic syndromes and secondary acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2019;33:686–95.

Kröger N. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for elderly patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2012;119:5632–9.

Abedin S, Lian Q, Martens MJ, Al Malki MHDMM, Elmariah H, Gooptu M, et al. Superiority of post-transplant cyclophosphamide-based graft versus host disease (GvHD) prophylaxis in patients 70 years and older: a BMT CTN 1703 post-hoc analysis. Blood. 2024;144:1042.

Scott BL, Pasquini MC, Logan BR, Wu J, Devine SM, Porter DL, et al. Myeloablative versus reduced-intensity hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1154–61.

Bolanos-Meade J, Hamadani M, Wu J, Al Malki MM, Martens MJ, Runaas L, et al. Post-transplantation cyclophosphamide-based graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:2338–48.

Broers AEC, de Jong CN, Bakunina K, Hazenberg MD, van Marwijk Kooy M, de Groot MR, et al. Posttransplant cyclophosphamide for prevention of graft-versus-host disease: results of the prospective randomized HOVON-96 trial. Blood Adv. 2022;6:3378–85.

Hassan K, Baranwal A, Mangaonkar AA, Hefazi M, Matin A, Litzow MR, et al. Risk of relapse post reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplant in patients with high-risk myeloid neoplasms based on Ptcy vs. TAC/MTX Gvhd prophylaxis. Blood. 2024;144:4918.

McGowan-Jordan J, Hastings R, Moore S. Re: International System for Human Cytogenetic or Cytogenomic Nomenclature (ISCN): some thoughts, by T. Liehr. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2021;161:225–6.

Elena C, Gallì A, Such E, Meggendorfer M, Germing U, Rizzo E, et al. Integrating clinical features and genetic lesions in the risk assessment of patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2016;128:1408–17.

Tefferi A, Fathima S, Abdelmagid M, Alsugair A, Aperna F, Rezasoltani M, et al. BLAST: a globally applicable and molecularly versatile survival model for chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2025;146:874–6.

Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, Baron F, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106:2912–9.

Karnofsky D, Burchenal J. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: Evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents. New York: Columbia University Press; 1949. pp. 191–205.

Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Kumar A, Ayala E, Aljurf M, Nishihori T, Marsh R, et al. Standardizing definitions of hematopoietic recovery, graft rejection, graft failure, poor graft function, and donor chimerism in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report on behalf of the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. Transplant Cell Ther. 2021;27:642–9.

Holtan SG, DeFor TE, Lazaryan A, Bejanyan N, Arora M, Brunstein CG, et al. Composite end point of graft-versus-host disease-free, relapse-free survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2015;125:1333–8.

Symeonidis A, van Biezen A, de Wreede L, Piciocchi A, Finke J, Beelen D, et al. Achievement of complete remission predicts outcome of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. A study of the Chronic Malignancies Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2015;171:239–46.

Patnaik MM, Wassie EA, Padron E, Onida F, Itzykson R, Lasho TL, et al. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia in younger patients: molecular and cytogenetic predictors of survival and treatment outcome. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5:e270.

Liu HD, Ahn KW, Hu ZH, Hamadani M, Nishihori T, Wirk B, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for adult chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2017;23:767–75.

Eissa H, Gooley TA, Sorror ML, Nguyen F, Scott BL, Doney K, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: relapse-free survival is determined by karyotype and comorbidities. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:908–15.

Wedge E, Hansen JW, Dybedal I, Creignou M, Ejerblad E, Lorenz F, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: clinical and molecular genetic prognostic factors in a Nordic population. Transplant Cell Ther. 2021;27:991.e1–e9.

Alyamany R, Alnughmush A, Remberger M, Michelis F, Law AD, Lam W, et al. Strength to endure: superiority of MAC over RIC in patients <65 years undergoing stem cell transplantation using ATG-Ptcy-CSA for Gvhd prophylaxis. Blood 2024;144:4863.

Scott BL, Pasquini MC, Fei M, Fraser R, Wu J, Devine SM, et al. Myeloablative versus reduced-intensity conditioning for hematopoietic cell transplantation in acute myelogenous leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes—long-term follow-up of the BMT CTN 0901 Clinical Trial. Transpl Cell Ther. 2021;27:483 e1–e6.

Nagler A, Labopin M, Dholaria B, Wu D, Choi G, Aljurf M, et al. Graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with post-transplantation cyclophosphamide versus cyclosporine A and Methotrexate in matched sibling donor transplantation. Transpl Cell Ther. 2022;28:86.e1–e8.

Itonaga H, Iwanaga M, Aoki K, Aoki J, Ishiyama K, Ishikawa T, et al. Impacts of graft-versus-host disease on outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: a nationwide retrospective study. Leuk Res. 2016;41:48–55.

Schroeder T, Wegener N, Lauseker M, Rautenberg C, Nachtkamp K, Schuler E, et al. Comparison between upfront transplantation and different pretransplant cytoreductive treatment approaches in patients with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome and secondary acute myelogenous leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:1550–9.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Mayo Clinic’s department of hematology for providing us with patient data which is not available commercially.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AT and AS designed the study, collected data, performed analyses, and drafted the paper. EM, MA, SF, NG, and MP designed the study, collected data and performed analyses. MY and AB contributed to data abstraction and drafted the paper. JF, AM, ML, HM, LS, JP, WH, MS, SC, NP, NK, LP, AM, SK, MI, EA, JS, and HA provided patient care.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MVS: Research funding to the institution from AbbVie, Astellas, Celgene, KURA Oncology, and Marker Therapeutics. AT is a co-editor of BCJ but was not involved in either the review or the decision process of the current paper.

Ethics approval and Consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Mayo Clinic (IRB protocol number:12-003574). All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the relevant guidelines, and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alsugair, A., Gauto Mariotti, E., Alhousani, M.M. et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: analysis of post-transplant survival and risk factors in 138 Mayo Clinic patients. Blood Cancer J. 15, 157 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01359-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01359-w