Abstract

Baseline cytomolecular features and measurable residual disease (MRD) dynamics are both strongly prognostic in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Whether early MRD response can overcome the adverse prognosis of high-risk (HR) cytomolecular features is largely unknown. We retrospectively identified 161 patients with newly diagnosed B-cell ALL who underwent MRD assessment with next-generation sequencing (NGS) for IG/TR rearrangements (sensitivity: 1 × 10−6). Early NGS MRD negativity (i.e. after 1 cycle of induction) was achieved in 33% of patients. Rates of NGS MRD negativity were similar in patients with standard-risk (SR) and HR cytomolecular features. Patients who achieved early NGS MRD negativity had the best outcomes (2-year relapse-free survival (RFS): 94% versus 66% if MRD-positive; P = 0.03). None of the 26 patients with early NGS MRD negativity subsequently relapsed. Early NGS MRD response also identified patients with HR Philadelphia-chromosome (Ph)-negative ALL with low risk of relapse and excellent long-term survival (2-year RFS: 100%); in contrast, the 2-year RFS was 38% for patients with HR ALL who remained MRD-positive after induction (P = 0.01). Outcomes remained poor for HR patients who achieved NGS MRD negativity at later timepoints. In a landmark analysis, allogeneic stem cell transplant (alloSCT) improved outcomes of patients with HR Ph-negative ALL who remained MRD-positive after induction (2-year RFS 80% versus 0% if no alloSCT; P = 0.009). In patients with B-cell ALL, achievement of early NGS MRD negativity is associated with durable remissions, regardless of baseline cytomolecular features. AlloSCT may improve outcomes of patients with HR ALL with suboptimal early MRD dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Achieving measurable residual disease (MRD) negativity is a critical endpoint in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) that strongly correlates with improved long-term survival and reduced relapse risk [1]. While several MRD assays are available for B-cell ALL, next-generation sequencing (NGS) for immunoglobulin (IG) and T-cell receptor (TR) rearrangements is the most sensitive (sensitivity: 1 × 10⁻⁶) and has become widely used in clinical practice [2]. Compared with multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR), NGS-based MRD assessment has demonstrated superior predictive value in predicting relapse [3,4,5]. Early achievement of MRD negativity is associated with favorable outcomes across several studies, although most of the published studies evaluated MRD by MFC or PCR. With these less sensitivity assays, relapses rates up to 25% have still been observed in MRD-negative patients, likely due to persistent leukemia below the level of detection of the assay [6,7,8]. However, early achievement of MRD negativity may be more protective when higher sensitivity NGS-based assays are used. For example, in one study of patients with Philadelphia chromosome (Ph)-negative ALL undergoing frontline therapy, none of the patients who reached early NGS MRD negativity after frontline therapy relapsed [3].

Current treatment guidelines recommend consideration of allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) for patients with high-risk (HR) ALL, irrespective of MRD dynamics. However, alloSCT can be associated with substantial treatment-related mortality [9], and therefore proper identification of patients in whom alloSCT can be safely deferred is imperative. Despite the established importance of MRD on ALL risk stratification, the prognostic impact of MRD dynamics using high-sensitivity NGS-based assays in HR ALL is largely unknown. It is also uncertain whether early achievement of deep MRD negativity can overcome the historically unfavorable prognosis of ALL harboring HR cytomolecular features. We therefore conducted a retrospective analysis evaluating high sensitivity NGS MRD for IG/TR in patients with B-cell ALL, including those with HR cytogenetic and/or genomic alterations. We also sought to evaluate whether early MRD dynamics can identify patients with HR B-cell ALL who may have favorable outcomes even without alloSCT in first remission.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is a retrospective study evaluating the prognostic impact high-sensitivity NGS MRD for IG/TR in adults with B-cell ALL. Eligible patients received frontline ALL therapy at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) between December 2016 and June 2024. Patients may have received a chemotherapy-based regimen using a backbone of hyper-CVAD or mini-hyper-CVD (depending on age and fitness) or a chemotherapy-free regimen (e.g. blinatumomab plus a BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitor [TKI] for Ph-positive ALL) [10,11,12]. Patients were required to have achieved complete remission (CR) as best response after the first cycle of therapy. Patients were selected for inclusion based on the availability of at least one NGS MRD assessment performed between the end of induction (i.e. ~1 month from the start of treatment) to ~6 months from the start of treatment. This study was conducted at a single academic center (MDACC). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MDACC and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

NGS MRD assessment, interpretation, and analysis

The clonoSEQ® MRD assay (Adaptive Biotechnologies Co., Seattle, WA) is an NGS-based immunosequencing assay that was used for this analysis, as previously described [3]. This MRD method tracks IG and/or TR sequences and has an analytical sensitivity of 0.0001% (1 × 10−6). For this study in B-cell ALL, only IG-calibrated samples (e.g. IGH, IGK, and/or IGL) were used for MRD assessment. Samples for NGS MRD assessment were performed both prospectively as part of routine clinical care and retrospectively from banked bone marrow samples.

NGS MRD results were classified as positive, negative, or below the level of detection (LOD). MRD negativity was defined as no detectable residual sequences in any trackable clonotype with a sensitivity of at least 1 × 10−6. A bone marrow sample was required to confirm NGS MRD negativity, while a peripheral blood sample could be used to document NGS MRD positivity. MRD assessments were classified into 3 timepoints for analysis: after the induction cycle (e.g. ~1 month from the start of treatment), ~3 months, and ~6 months from the start of treatment. Only MRD assessments performed during frontline therapy and prior to any change of therapy (e.g. alloSCT or CAR T-cell therapy) were analyzed. For the primary analyses of time-dependent relapse and survival outcomes, only MRD-positive and MRD-negative groups were compared. Given the variability in clinical significance of MRD detected below LOD, these cases were excluded from the survival analyses [2].

Response and outcome definitions

CR was defined as <5% blasts in the bone marrow with an absolute neutrophil count ≥1 × 109/L and platelet count of ≥100 × 109/L. Relapse was defined as recurrence of bone marrow blasts >5% and/or extramedullary ALL. Relapse free survival (RFS) was calculated from the time of CR until relapse or death from any cause, censored if the patient was alive at last follow-up.

Statistical methods

Patient characteristics were summarized using median (range) for continuous variables and frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables. To compare two groups, Fisher’s exact test was performed for categorical variables, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed for continuous variables. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the probabilities for RFS and differences between groups were evaluated with the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.

Results

Patient characteristics

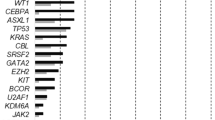

A total of 161 patients with B-cell ALL met the study inclusion criteria and had at least 1 NGS MRD assessment. The baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The median age of the cohort was 46 years (range, 18–87 years). Fifty-one patients (32%) had Ph-positive ALL and 110 (68%) had Ph-negative ALL. For frontline therapy, 69 patients (43%) received a hyper-CVAD-based regimen (usually with the addition of blinatumomab and/or inotuzumab), 45 (28%) received a lower-intensity mini-hyper-CVD-based regimen (all with the addition of blinatumomab and/or inotuzumab), and 47 (29%) received a chemotherapy-free regimen (exclusively in the Ph-positive ALL subgroup). Treatment regimens by subgroup are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Among the 110 patients with Ph-negative B-cell ALL, 59 (54%) had at least one HR baseline cytomolecular feature, defined as either poor-risk cytogenetics (i.e. low hypodiploidy/near triploidy, complex cytogenetics [i.e. presence of ≥5 chromosomal abnormalities], or KMT2A rearrangement), Ph-like ALL, and/or a TP53 mutation.

Patient disposition

The median duration of follow-up for the entire study population was 22 months (range, 2–85 months). Overall, 24 patients (15%) underwent alloSCT in first remission (1 of whom subsequently relapsed), 7 (4%) underwent CAR T-cell consolidation in first remission (1 of whom subsequently relapsed), 12 (7%) relapsed in the absence of alloSCT or CAR T-cells, 8 (7%) died in remission, and 111 (69%) are alive without relapse without alloSCT or CAR T-cell consolidation. Among the 14 total relapses, the median time to relapse was 8.6 months (range, 3.8–20.3 months). Among those who relapsed, 5/14 (36%) had Ph-positive ALL and 9/14 (64%) had Ph-negative ALL.

Rates of NGS MRD negativity

Patients had a median of 2 (range, 1–3) NGS MRD assessments performed over the study period. Overall, 121 patients (75%) had a trackable IGH sequence, and 40 patients only had a trackable IGK and/or IGL sequence (IGK in 32 patients [20%] and IGL in 8 patients [5%]). NGS MRD information was available in 79 patients (49%) at the end of induction, 113 (70%) after 3 months, and 83 (52%) after 6 months. Among patients with Ph-negative B-cell ALL, 47/84 (56%) had received blinatumomab by the 3-month assessment and 53/55 (96%) by the 6-month assessment.

The rates of MRD negativity increased with time in the overall cohort and within individual subgroups (Table 2). For the entire, cohort, the rate of MRD negativity was 33% (26/79) at the end of induction, 65% (74/113) after 3 months, and 83% (69/83) after 6 months. Among patients with Ph-positive ALL, the rate of MRD negativity was 38% (10/26) at the end of induction, 72% (23/32) after 3 months, and 84% (27/32) after 6 months, and for patients with Ph-negative ALL, the rates of MRD negativity at these timepoints were 30% (16/53), 63% (51/81), and 82% (42/51), respectively. The rates of NGS MRD negativity were similar between HR and standard-risk (SR) Ph-negative patients at each timepoint. NGS MRD negativity after induction was achieved in 36% of HR patients versus 25% of SR patients. Rates of MRD negativity for HR and SR patients after 3 months were 62% and 64%, respectively, and after 6 months were 85% and 79%, respectively. The specific cytomolecular features of the 9 patients with HR Ph-negative B-cell ALL who achieved NGS MRD negativity after cycle 1 are shown in Supplementary Table 2. Rates of MRD negativity for the different HR cytomolecular subgroups at each timepoint are shown in Supplementary Table 3. Furthermore, high WBC at diagnosis (i.e. ≥30 ×109/L) did not significantly impact rates of NGS MRD negativity in any subgroup and/or timepoint.

Impact of NGS MRD response on relapse and survival

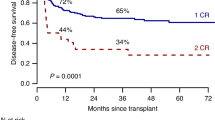

For the entire cohort, NGS MRD negativity was associated with superior outcomes at all timepoints (Fig. 1). Among the 26 patients who achieved MRD negativity after induction, 16 (62%) had Ph-negative ALL, 10 (38%) had Ph-positive ALL, and no patient relapsed. One of these patients with early NGS MRD negativity died in remission. The 2-year RFS rate for patients who were MRD-negative after induction was 94% versus 66% for those who were MRD-positive (P = 0.03). The 2-year RFS rates at 3 months were 82% and 65%, respectively (P = 0.08), and at 6 months were 82% and 62%, respectively (P = 0.01). The impact of NGS MRD response was greater in patients with Ph-negative ALL than in those with Ph-positive ALL. For patients with Ph-positive ALL, achievement of MRD negativity was not significantly associated with better RFS at any time point, although the number of patients evaluable at each timepoint was relatively small (Supplementary Fig. 1). In contrast, in patients with Ph-negative ALL, achievement of MRD negativity was significantly associated with superior outcomes at each timepoint (Supplementary Fig. 2). Among the 16 patients with Ph-negative ALL who achieved MRD negativity after induction (9 of whom had HR disease), none has relapsed with a median follow-up of 16 months (range, 6–83 months). In the Ph-negative ALL subgroup, the 2-year RFS rate for patients who were MRD-negative after induction was 100% versus 69% for those who were MRD-positive (P = 0.03). The 2-year RFS rate at 3 months was 83% and 60%, respectively (P = 0.04), and at 6 months was 87% and 50%, respectively (P < 0.001).

Interaction of NGS MRD response and cytomolecular risk on relapse and survival in Ph-negative ALL

Given the more prominent impact of NGS MRD response on long-term outcomes in Ph-negative ALL, we focused further analyses in this subgroup, including stratification by baseline cytomolecular risk. In patients with SR Ph-negative ALL, outcomes were excellent regardless of MRD response after induction (Fig. 2A). The 2-year RFS rates for SR patients who achieved MRD negativity after induction versus those who remained MRD-positive were 100% and 94%, respectively (P = 0.53). Among 26 SR patients with evaluable NGS MRD after induction, only 1 patient relapsed (MRD-positive group). In contrast, for patients with HR Ph-negative ALL, a striking difference in outcomes was observed according to early MRD response (Fig. 2B). The 2-year RFS rate was 100% for HR patients who achieved MRD-negativity after induction, versus 38% in MRD-positive patients (P = 0.01).

To better understand the impact of MRD dynamics in patients with Ph-negative B-cell ALL, we categorized patients as: “Early responders” (i.e. achievement of MRD negativity after induction), “Late responders” (i.e. MRD-positivity after induction then conversion to MRD negativity at a later timepoint), or “Non-responders” (i.e. lack of achievement of MRD negativity during the study period). In patients with SR Ph-negative ALL, outcomes were excellent regardless of MRD dynamics, although outcomes were suboptimal for patients who did not achieve MRD negativity during the first 6 months of treatment (Supplementary Fig. 3). The 2-year RFS rate was 100% for both early or late responders and was 54% for non-responders. Among the 7 MRD non-responders in the SR group, 1 relapsed. In patients with HR Ph-negative ALL, the 2-year RFS rates for early responders, late responders, and non-responders were 100%, 25%, and 56%, respectively (Fig. 3). Notably, alloSCT rates were numerically higher in the non-responder group (7/14; 50%) as compared with the late responder group (3/9; 33%).

Impact of alloSCT on relapse and survival outcomes in Ph-negative ALL

The overall rate of alloSCT consolidation in patients with Ph-negative ALL was 22% (24/110). No patient with Ph-positive ALL in our cohort underwent alloSCT. Among the 24 patients with Ph-negative ALL who underwent alloSCT in first remission, 21 (88%) had a HR cytomolecular feature. The rate of alloSCT consolidation was higher in patients with HR than with SR Ph-negative ALL (35% versus 6%, respectively; P < 0.001).

We performed a landmark analysis to evaluate the impact of alloSCT in patients with HR Ph-negative B-cell ALL, stratified by their MRD response. The median time to alloSCT was 5.5 months (range, 2.6–30.1 months). As previous described, none of the 9 HR patients who achieved NGS MRD negativity after induction relapsed, including the 7 patients in this group who did not undergo alloSCT in first remission (Supplementary Fig. 4). In contrast, alloSCT appeared to benefit patients with HR Ph-negative ALL with suboptimal early MRD response. Among patients with HR Ph-negative ALL who were MRD-positive after induction, the 2-year RFS rates for patients who underwent alloSCT versus did not were 80% and 0%, respectively (P = 0.009) (Fig. 4A). Similarly, for patients who were MRD-positive at 3 months from the start of therapy, the 2-year RFS rates were 86% and 21%, respectively (P = 0.02) (Fig. 4B). There were not enough patients in each group to perform the same analysis at the 6-month timepoint.

Discussion

In patients with B-cell ALL, achievement of NGS MRD negativity is associated with more durable remissions and better long-term outcomes across a variety of therapeutic contexts, including after frontline chemotherapy and in the peri-transplant settings [3,4,5, 13, 14]. However, despite the established benefit of achieving NGS MRD negativity, the impact of these deep MRD responses in different cytomolecular groups has not been well-described. In this analysis, patients with HR cytomolecular features who achieved early NGS MRD negativity (i.e. after 1 cycle of induction) had excellent long-term survival, with no relapses observed and a 2-year RFS rate of 100%. Importantly, patients who remained NGS MRD-positive after induction—even if MRD cleared with subsequent cycles—had poor outcomes, and they benefitted from alloSCT consolidation in first remission. These findings suggest that for patients with HR ALL, early NGS MRD response may overcome the historically poor prognosis of these HR cytomolecular features.

Our findings have several important implications for the management of newly diagnosed ALL. Patients with ALL harboring HR cytomolecular features are often recommended to undergo alloSCT in first remission, regardless of MRD response to frontline therapy [9]. However, our analysis as well as several recent publications challenge this approach. For example, in the E1910 study which enrolled patients in MFC MRD-negative after induction/intensification, there was no benefit with alloSCT in patients with HR Ph-negative B-cell ALL (3-year OS 71% for transplanted patients versus 90% for non-transplanted patients) [15]. Similarly, in a GRAALL study of 522 patients with HR ALL, alloSCT benefited patients with MRD > 0.1% by PCR for IG/TR after induction but not those with early MRD negativity [16]. In this analysis, patients with HR ALL and good early MRD response had a 3-year OS of 60–70%. In contrast, our study used a highly sensitive NGS MRD assay and strictly defined “MRD negativity” as absence of any detectable residual sequences with a sensitivity of at least 1 × 10−6, which in part explains the superior outcomes for the HR patients in our analysis who achieved early MRD-negativity. While we did not observe any relapses in patients with HR Ph-negative ALL with early NGS MRD response, there were only 7 patients in this group who did not undergo alloSCT, which limits our ability to make definitive conclusions about the role of consolidative alloSCT in this population.

Importantly, we showed that for patients with HR cytomolecular features, only achievement of NGS MRD negativity after the first cycle of induction led to favorable survival outcomes and durable remissions. In contrast, later clearance of MRD was not protective against relapse, as these late MRD responders with HR ALL had a 3-year RFS rate of only 25%. The relatively poor outcomes of patients with late MRD clearance are consistent with several prior analyses, using a variety of MRD methodologies [3, 6, 7, 17, 18]. AlloSCT benefitted patients with HR Ph-negative ALL with suboptimal early MRD kinetics and led to a 3-year RFS rate of 80%, suggesting that alloSCT should be strongly considered for patients with HR Ph-negative ALL who do not achieve early NGS MRD negativity. Whether alternative consolidative strategies such as CAR T-cell therapy can provide a similar benefit with lower risk of treatment-related mortality is being actively explored. Early data with CAR T-cell consolidation in older adults who are not suitable candidates for alloSCT are encouraging, although the durability of these remissions and the impact of initial MRD response and baseline cytomolecular features are still unknown [19]. Several other studies evaluating CAR T-cell consolidation after frontline therapy for patients with HR features are ongoing.

While our results suggest that many patients with HR ALL who achieve early and deep MRD negativity can have excellent outcomes even without alloSCT in first remission, it is important to note that our findings may not be generalizable to all HR cytomolecular features. Among those with HR Ph-negative ALL with early NGS MRD clearance, most patients were classified as HR based on complex cytogenetics and/or a TP53 mutation, while only 2 patients had Ph-like ALL, 1 had low-hypodiploidy/near-triploidy, and none had a KMT2A rearrangement. While all the above cytomolecular features are classified as HR by consensus guidelines [9], the prognostic impact of MRD likely varies across HR cytomolecular features [20]. Given the relatively small number of patients in our study with HR disease, larger studies evaluating the MRD dynamics using a high-sensitivity NGS MRD assay in each of these individual HR cytomolecular subgroups are needed to help individualize consolidative strategies for patients with HR ALL. Early NGS MRD negativity appears to best identify patients with HR cytomolecular features who are at relatively low risk of relapse. However, due to the retrospective nature of our study, NGS MRD assessment was not performed at all timepoints, limiting our ability to evaluate how MRD kinetics influence outcomes across ALL subgroups.

The impact of MRD dynamics in ALL may vary according to the treatment delivered, and therefore our data may not apply to other treatment regimens. In our analysis, all patients with Ph-negative ALL received a hyper-CVAD or mini-hyper-CVD-based regimen, with 96% of patients with Ph-negative ALL receiving blinatumomab within the first 6 months. While we do not have data on the impact of NGS MRD dynamics with other regimens (e.g. pediatric-inspired regimens), our findings are likely to be applicable to most contemporary frontline ALL protocols that integrate blinatumomab into consolidation regardless of MRD status. As new strategies with earlier incorporation of blinatumomab during induction are being evaluated, the prognostic impact of NGS MRD dynamics and early NGS MRD negativity across cytomolecular risk groups should be reassessed in those specific therapeutic contexts.

Interestingly, we did not observe a significant impact of NGS MRD dynamics in patients with Ph-positive ALL in our cohort. While several prior analyses have shown the benefit of achieving MRD-negativity in Ph-positive ALL, most studies have evaluated MRD using PCR for BCR::ABL1 in patients treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy plus a BCR::ABL1 TKI [8, 21]. In contrast, 92% of patients with Ph-positive ALL in our cohort received frontline blinatumomab plus a TKI (34 of whom [72%] received ponatinib and 13 of whom [28%] received other TKIs). The prognostic impact of early MRD dynamics and HR cytomolecular features is less clear with these chemotherapy-free regimens. In the D-ALBA study, both IKZF1plus genotype and lack of early complete molecular response (i.e. MRD-negativity by PCR for BCR::ABL1) were associated with worse outcomes [22]. In contrast, in a recent analysis of blinatumomab plus ponatinib, only white blood cell (WBC) count ≥70 ×109/L at diagnosis—but neither MRD response nor IKZF1plus genotype—was independently associated with an increased risk of relapse [23]. Future studies are needed to better understand the relative impact of clinical/cytomolecular features and MRD dynamics in Ph-positive ALL treated with different chemotherapy-free regimens.

In summary, we found that early achievement of NGS MRD negativity was associated with favorable long-term outcomes in Ph-negative B-cell ALL, including in HR patients. In contrast, patients with HR Ph-negative ALL who do not rapidly achieve NGS MRD negativity after frontline therapy have poor outcomes but may be salvaged with alloSCT in first remission. Our findings suggest that early NGS MRD dynamics can further risk stratify patients with HR ALL and may help to guide decisions about consolidative therapy.

Data availability

For original deidentified data, please contact the corresponding author. Sharing will be considered upon reasonable request.

References

Berry DA, Zhou S, Higley H, Mukundan L, Fu S, Reaman GH, et al. Association of minimal residual disease with clinical outcome in pediatric and adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:e170580.

Short NJ, Aldoss I, DeAngelo DJ, Konopleva M, Leonard J, Logan AC, et al. Clinical use of measurable residual disease in adult ALL: recommendations from a panel of US experts. Blood Adv. 2025;9:1442–51.

Short NJ, Kantarjian H, Ravandi F, Konopleva M, Jain N, Kanagal-Shamanna R, et al. High-sensitivity next-generation sequencing MRD assessment in ALL identifies patients at very low risk of relapse. Blood Adv. 2022;6:4006–14.

Kotrová M, Koopmann J, Trautmann H, Alakel N, Beck J, Nachtkamp K, et al. Prognostic value of low-level MRD in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia detected by low- and high-throughput methods. Blood Adv. 2022;6:3006–10.

Short NJ, Jabbour E, Macaron W, Ravandi F, Jain N, Kanagal-Shamanna R, et al. Ultrasensitive NGS MRD assessment in Ph+ ALL: prognostic impact and correlation with RT-PCR for BCR::ABL1. Am J Hematol. 2023;98:1196–203.

Stock W, Luger SM, Advani AS, Yin J, Harvey RC, Mullighan CG, et al. A pediatric regimen for older adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of CALGB 10403. Blood. 2019;133:1548–59.

Yilmaz M, Kantarjian H, Wang X, Khoury JD, Ravandi F, Jorgensen J, et al. The early achievement of measurable residual disease negativity in the treatment of adults with Philadelphia-negative B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia is a strong predictor for survival. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:144–50.

Short NJ, Jabbour E, Sasaki K, Patel K, O’Brien SM, Cortes JE, et al. Impact of complete molecular response on survival in patients with Philadelphia chromosome–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2016;128:504–7.

NCCN Guidelines. NCCN. 2025. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1410.

Short NJ, Jabbour E, Jamison T, Paul S, Cuglievan B, McCall D, et al. Dose-dense mini-hyper-CVD, inotuzumab ozogamicin and blinatumomab achieves rapid MRD-negativity in philadelphia chromosome-negative B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2024;24:e168–73.

Kantarjian H, Short NJ, Jain N, Haddad FG, Kadia T, Yilmaz M, et al. Hyper-CVAD and sequential blinatumomab without and with inotuzumab in young adults with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-negative B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2025;100:402–7.

Kantarjian H, Short NJ, Haddad FG, Jain N, Huang X, Montalban-Bravo G, et al. Results of the simultaneous combination of ponatinib and blinatumomab in Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:4246–51.

Pulsipher MA, Han X, Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Qayed M, Rives S, et al. Next-generation sequencing of minimal residual disease for predicting relapse after tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Cancer Discov. 2022;3:66–81.

Liang EC, Dekker SE, Sabile JMG, Torelli S, Zhang A, Miller K, et al. Next-generation sequencing-based MRD in adults with ALL undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood Adv. 2023;7:3395–402.

Liedtke M, Sun Z, Litzow MR, Mattison RJ, Paietta E, Roberts KG, et al. Assessment of outcomes of allogeneic stem cell transplantation by treatment arm in newly diagnosed measurable residual disease negative patients with B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia randomized to conventional chemotherapy +/- blinatumomab in the ECOG-ACRIN E1910 phase III national clinical trials network trial. Blood. 2024;144:779.

Dhédin N, Huynh A, Maury S, Tabrizi R, Beldjord K, Asnafi V, et al. Role of allogeneic stem cell transplantation in adult patients with Ph-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125:2486–96.

Brüggemann M, Raff T, Flohr T, Gökbuget N, Nakao M, Droese J, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease quantification in adult patients with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:1116–23.

Gökbuget N, Dombret H, Giebel S, Bruggemann M, Doubek M, Foà R, et al. Minimal residual disease level predicts outcome in adults with Ph-negative B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematol Amst Neth. 2019;24:337–48.

Aldoss I, Wang X, Zhang J, Guan M, Espinosa R, Agrawal V, et al. CD19-CAR T cells as definitive consolidation for older adults with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first complete remission: a pilot study. Blood. 2024;144:966.

O’Connor D, Enshaei A, Bartram J, Hancock J, Harrison CJ, Hough R, et al. Genotype-specific minimal residual disease interpretation improves stratification in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2018;36:34–43.

Ghobadi A, Slade M, Kantarjian H, Alvarenga J, Aldoss I, Mohammed KA, et al. The role of allogeneic transplant for adult Ph+ ALL in CR1 with complete molecular remission: a retrospective analysis. Blood. 2022;140:2101–12.

Foà R, Bassan R, Elia L, Piciocchi A, Soddu S, Messina M, et al. Long-term results of the dasatinib-blinatumomab protocol for adult philadelphia-positive ALL. J Clin Oncol J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2024;42:881–5.

Short NJ, Kantarjian H, Furudate K, Jain N, Ravandi F, Karrar O, et al. Molecular characterization and predictors of relapse in patients with Ph + ALL after frontline ponatinib and blinatumomab. J Hematol OncolJ Hematol Oncol. 2025;18:55.

Funding

Adaptive Biotechnologies Co. performed the NGS MRD assay on retrospective samples at no cost to the authors. Supported by an MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant (CA016672) and SPORE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NJS designed the study, analyzed the data, treated patients, and wrote the first version of the manuscript; WM collected and analyzed the data, performed statistical analyses and wrote the first version of the manuscript; EJ designed the study and treated patients; NJ, FGH, JS, TMK, PK, EK, FR and HK treated patients; SL and JM collected the data; and RG collected and analyzed the data. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approve of the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

NJS, EJ, and NJ have received consulting fees and honoraria from Adaptive Biotechnologies. FGH received consulting fees from Amgen. The other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MD Anderson Cancer Center (Reference No. PA18-0025) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Short, N.J., Jabbour, E., Macaron, W. et al. Prognostic impact of early NGS MRD dynamics and cytomolecular risk in newly diagnosed B-cell ALL. Blood Cancer J. 15, 169 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01373-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01373-y