Abstract

Most myelofibrosis (MF) drug approvals by Health Authorities are based on 1 or 2 outcome measures such as spleen volume reduction and/or improved quality of life. This 1–2 dimensional approach fails to capture the clinical complexity of MF. A European LeukemiaNet (ELN) task force developed a composite endpoint that allows multiple outcomes to be simultaneously measured. The panel used the Desirability Of Outcome Ranking (DOOR) method to assign 25 outcomes into 4 quartiles based on a multi-dimensional desirability score and build a 5-layer composite outcome named Desirability of Myelofibrosis Outcomes (DEMYO). Outcome operational definitions were tested by Delphi consensus, and correlations with survival were validated by a literature review. The outcomes assigned to the first two quartiles were negatively correlated with leukemia-free survival and survival. DEMYO comprehensively captures relevant MF clinical features and meaningful endpoints. Despite DEMYO requiring validation based on available trial data, it is expected to improve the quality of Health Authority approvals for new drugs for MF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Myelofibrosis (MF) is a complex disease with diverse adverse health-related features [1]. Most recent drug approvals by Health Authorities were based on 1–2 surrogate endpoints such as spleen volume and/or improved quality of life (QoL). This limited approach does not allow to estimate how many people benefit from a new MF drug [2].

A European LeukemiaNet panel developed a composite endpoint for approval of new MF drugs by Health Authorities using the Desirability Of Outcome Ranking (DOOR) method, which supports the development of a stratified multi-level composite endpoint by selecting the most relevant endpoints and the most appropriate combination rule [3]. Using the DOOR method, the panel developed a five-layered composite outcomes measure termed Desirability of Myelofibrosis Outcomes (DEMYO). Results are described below.

Materials and methods

The panel consisted of 14 key opinion leaders from 5 European countries and the US. The project adhered to the DOOR method (Fig. 1), which ranks patient health statuses according to different outcomes that occurred during the observation period. DOOR therefore ranks different Event-Free Survival statuses according to the severity of the events. Patients who survive free of both severe and less severe events are assigned a higher rank than patients who survive free of severe events but incur moderate or mild events. Therefore, the DOOR method requires first that the “desirability” of the events is settled. However, the desirability of a clinical event has several dimensions, and points of view may differ on its relative weight for the patient. Therefore, outcome desirability is usually broken down into components. Subsequently, each outcome is matched to the dimensions of desirability. This match allows us to finally assign a score to each outcome and rank the outcomes into severe, moderate, or mild.

DOOR grades disease-related health status from the worst state (rank 0) to the best one (rank 4) based on the number and severity of the reported events (e.g., vascular events) occurring during the observational time frame or the conditions reported at the end of the time frame (e.g., transfusion-dependent anemia).

First phase: definition of outcome desirability

The initial phase DOOR method requires listing the criteria for judging “desirability” of outcomes (Fig. 2). The panelists listed and ranked 8 dimensions of outcome desirability (Supplementary Table 1): (1) modifiability; (2) reliability; (3) decisional value; (4) feasibility; (5) meaningfulness (to patients); (7) frequency; and (8) cost. We adapted the list and definition of the above dimensions based on several initiatives devoted to the value of cancer care developed by the American Society of Oncology, the European Society of Medical Oncology, and the Canadian Center for Applied Research in Cancer Control.

Next, a weight was assigned to each dimension using the mean score assigned by the panelists: the score was based on a semi-quantitative Likert scale ranging from 1 (absolutely poorly relevant) to 7 (absolutely very relevant). The desirability dimensions scoring >6 were assigned a weight of 8, those scoring 4 to 6, 3, and those scoring <4 to 1 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Weights were assigned to maximize the rank difference among the dimensions.

Second phase: outcome ranking based on their desirability

Next, the panel agreed on a list of 25 clinical outcomes most frequently reported in clinical trials. Based on the list, panelists appraised which desirability dimension was accomplished by each outcome. In the 3rd step, a weighted score for each outcome was calculated (Supplementary Table 2) based on weights assigned to a dimension and accomplishment rates assigned to outcomes (Supplementary Table 3). The score for each outcome was a weighted average of the accomplishment rates for the eight desirability dimensions. Therefore, each percentage of accomplishment (outcome-dimension) was multiplied by a weight of 8, if the assessed dimensions were “meaningfulness,” “modifiability,” “reliability,” or “feasibility” (Supplementary Fig.1). The percentages of accomplishment of the outcome to “decisional value” and “acceptability” were multiplied by a weight of 3, while the percentages of accomplishment of the remaining outcomes were multiplied by a weight of 1. Finally, the mean of “weighted” accomplishment rates was calculated (Supplementary Table 2).

Based on the weighted score, outcomes were ranked into quartiles (Q1–Q4) (Supplementary Fig. 2): Q1 outcomes were the most desirable goals of therapy and included the most severe events or conditions, while Q3 and Q4 outcomes were mild events or conditions (Fig. 3). To limit the number of layers, Q4 outcomes were not further considered. Grade 3-4 non-hematologic adverse effects were not specifically addressed because of their rarity and heterogeneity according to the ongoing treatment. The standard 24-week time frame was the time point to assess outcomes.

Phase 3: outcome layer construction

Next, a 5-layer outcome was composed. Each layer was named DEMYO (Desirability of Myelofibrosis Outcome): death (DEMYO-0) was the least desirable layer, while DEMYO-4 was the most desirable one since it included people free of Q1, Q2 and Q3 outcomes (Fig. 4), that is free of blast phase, accelerated phase, thrombotic or bleeding events, and also free of relevant or worsening cytopenias or symptoms. In addition, patients in the DEMYO-4 state are also free of emergent adverse genetic abnormalities or increased blast count, which are known to dramatically reduce their chances of survival. As shown by Fig. 4, the higher the number of undesirable outcomes the patient is free of, the more his status is desirable. Therefore, DEMYO-3 was a less desirable health status, since it includes people free of Q1 and Q2 outcomes, but not free of Q3 outcomes. DEMYO-2 was even less desirable, since it hosts people free of Q1 outcomes, but possibly complaining of severe or worsening symptoms, worsening anemia, or having incurred an accelerated phase. At last, DEMYO-1 does not grant freedom from Q1 outcomes, therefore hosts patients who incurred blast phase transformation, severe vascular events, or major bleedings. DEMYO-1 also includes those MF individuals who complain of very severe symptoms and/or severe thrombocytopenia (Fig. 4).

DEMYO-4 patients survived free of overt severe or worsening clinical features and also free of breakthrough adverse genetic features or worsening markers. A less desirable health status is DEMYO-3: this layer collects patients surviving the trial period free of Q1 and Q2 outcomes, but incurring one or more Q3 outcomes. Such patients do not complain of severe or worsening symptoms or severe cytopenias, but present unfavorable clinical or genetic trajectories heralding transformation or worsening. DEMYO-2 is an even less desirable status: this outcome layer includes patients who survived free of Q1 outcomes (blast transformations, transfusion-dependent anemia, severe thrombocytopenia, very severe symptoms, severe vascular or bleeding events). However, DEMYO-2 patients have incurred one or more Q2 outcomes and might therefore complain of severe splenomegaly or worsening symptoms. Patients assigned to DEMYO-1 survived but complained of at least one Q1 outcome. VAF variant allele frequency. Incipient transformation points to patients with an increased circulating blast count above 5% confirmed after 4 weeks with no therapy change.

Phase 4: endpoint definition

Lastly, the panel provided operational definitions for each outcome to formulate “measurable endpoints.” Operational definitions were tested by a Delphi consensus method (Google module). Definitions with <75 per cent had a 2nd round of voting. A virtual meeting refined some definitions. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 5.0 [4], WHO and ICC diagnostic criteria [5, 6], ISTH major bleeding [7], and other standard definitions, such as IWG-MRT response criteria [8], were used where appropriate. Some formerly adopted definitions were modified including (1) “severe” splenomegaly [9, 10]; and (2) severity of symptoms according to Myelofibrosis Symptom Assessment Form (MF-SAF) [10,11,12] (Supplementary Table 4).

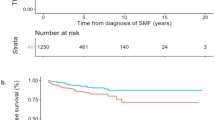

Phase 5: validation

Outcomes ranking was validated by assessing correlations with leukemia-free survival and survival (Supplementary Table 5). An EMBASE search of publications since 2015 was done with the Boolean search terms “survival AND myelofibrosis”.

Results

Outcome desirability

The panelists ranked “clinical meaningfulness” and “modifiability” as the dominant features of a “desirable treatment outcome.” An average score >6 (out of 7, the highest value in the semi-quantitative Likert scale) was also achieved by outcomes “reliability” and “feasibility.” Consequently, the above 4 desirability dimensions were assigned the highest weight, while “cost” and “frequency” of the outcomes were considered not relevant and therefore did not receive an additional weight (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Outcome ranking

In the next DOOR phase, an accomplishment rate was estimated for each outcome-dimension pair (Supplementary Table 3) and multiplied by the dimension weight (Supplementary Table 1). A weighted score was then calculated for each outcome by averaging the “refined accomplishment rates” across the 8 dimensions (Supplementary Fig. 2) [13]. The weighted score ranged from 15.25 to 32.18, and outcomes could be assigned to “desirability quartiles” Q1–Q4 (Fig. 3). Severe cytopenias, very severe symptoms, transformation to blast phase, and severe vascular or bleeding events were all top-ranked and were therefore listed in the first quartile, e.g., Q1. Mild or moderate cutopenias showing a worsening trajectory were assigned an intermediate score and were ranked to Quartile Q2. Severe or symptomatic splenomegaly was also assigned an intermediate score and ranked Q2. Differently, persistent cytopenias that were not severe or worsening were assigned a lower score and were therefore ranked in the third quartile, e.g., Q3.

DEMYO composite outcome

Based on the quartile outcome assignment, we built 5 layers for the DEMYO composite outcome (Fig. 4). DEMYO-4 represents survival free of all the relevant events or undesirable conditions listed in Q1, Q2, or Q3. Therefore, patients in DEMYO-4 survived free of transformation and do not show an increased blast count, e.g., an incipient transformation. Moreover, DEMYO-4 patients survived free of anemia and free of severe thrombocytopenia, and they are also free of severe or worsening symptoms and of severe or symptomatic splenomegaly. In addition, DEMYO-4 patients did not incur any clinically relevant thrombotic or bleeding event in the observation period. Finally, DEMYO-4 patients also proved free of worsening prognostic features, such as worsening thrombocytosis, no decline of founder mutation variant allelic frequency, and no breakthrough high-risk genetic features (newly detected adverse karyotypic features or newly detected high-risk mutation with an allelic burden higher than 2%).

Rather, patients assigned a DEMYO-2 state proved free only of those outcomes that impose a huge burden to their QoL (e.g., very severe symptoms) or an immediate survival risk(e.g., blast phase transformation, severe cytopenias, severe vascular events).

Validation

Our literature search found a consistent correlation with survival of most or all outcomes included in Q1–Q3 (Supplementary Table 5) [14]. Lastly, DEMYO outcomes were operationally defined (Table 1) to facilitate applicability as a composite multilayer trial endpoint.

Discussion

Endpoints used to approve new drugs for MF do not capture the complexity of the disease [15, 16]. We developed a composite endpoint that allows multiple outcomes to be simultaneously measured using the DOOR method. The DEMYO categories comprehensively capture relevant MF clinical features and meaningful endpoints and should improve the design of clinical trials and ameliorate the criteria for approvals of new MF drugs.

We anticipate several advantages of using DOOR and DEMYO. 1st, DEMYO overcomes the limited value of survival-based outcomes [17]. 2nd, DOOR-based composite outcomes include response rates. 3rd, the hierarchy was robust, and most of the selected outcomes correlated with survival.

Our study has some limitations. The replicability of DEMYO ranking is limited by the length and complexity of the process. In addition, the independent role of some components of the DEMYO framework cannot be ascertained from the available literature: we expect future DEMYO versions might be refined according to new evidence [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Moreover, trial design and analysis based on DOOR-based outcomes can be pursued by the DOOR statistic tool (https://methods.bsc.gwu.edu/), but simulation of DEMYO outcomes requires raw data from clinical trials, which were not available during this project [13]. Therefore, a simulated DOOR analysis of a randomized trial was included in Supplementary Fig. 3. Finally, validation of the DEMYO survival predictive yield was not completed: DEMYO prognostic value based on real-life or trial data might increase confidence in outcome robustness. Therefore, we are encouraging DEMYO post-hoc analysis of both completed and ongoing clinical trials and real-world studies, since most of the DEMYO component outcomes are routinely collected. We are constructing an app allowing direct bridging of raw data to the DEMYO assessment.

In conclusion, the DEMYO composite endpoints reflect endpoints important to physicians and people with MF. DEMYO endpoints should be validated in clinical trials and, if validated, used as the basis of future Health Authority approvals of new MF drugs.

Data availability

All data are in the Supplementary files.

Change history

27 January 2026

The correct affiliation for professor Prithviraj Bose is: 5 Department of Leukemia, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Prithviray Bose’s affiliation was erroneously reported as “5Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston Salem, NC, USA.”

References

Marchetti M. Ph-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms. In: Rezaei N, editor. Comprehensive hematology and stem cell resource. Elsevier Reference Collection in Biomedical Sciences. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1012/B978-0-443-15717-2.00015-9

Taylor RS, Manyara AM, Ross JS, Ciani O. Surrogate end points in trials—SPIRIT and CONSORT extensions. JAMA. 2024;332:1340.

Evans SR, Rubin D, Follmwn D, et al. Desirability of Outcome Ranking (DOOR) and Response Adjusted for Duration of Antibiotic Risk (RADAR). Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:800–6.

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_5x7.pdf Accessed 31st August.

Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, Akkari Y, Alaggio R, Apperley JF, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of haematolymphoid tumours: myeloid and histiocytic/dendritic neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36:1703.

Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian RP, Borowitz MJ, Calvo KR, Kvasniscka H-M, et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood. 2022;140:1200.

Schulman S, Kearon C. Subcommittee on control of anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:692.

Tefferi A, Cervantes F, Mesa, Passamonti F, Verstovsek S, Vannucchi AM, et al. Revised response criteria for myelofibrosis: International Working Group-Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and Treatment (IWG-MRT) and European LeukemiaNet (ELN) consensus report. Blood. 2013;122:1395.

Barbui T, Tefferi A, Vannucchi AM, Passamonti F, Silver RT, Hoffman R, et al. Philadelphia chromosome-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: revised management recommendations from European LeukemiaNet. Leukemia. 2018;32:1057.

Marchetti M, Barosi G, Cervantes F, Birgegard G, Griesshammer M, Harrison C, et al. Which patients with myelofibrosis should receive ruxolitinib therapy? ELN-SIE evidence-based recommendations. Leukemia. 2017;31:882.

Hudgens S, Verstovsek S, Floden L, Harrison CN, Palmer J, Gupta V, et al. Meaningful symptomatic change in patients with myelofibrosis from the SIMPLIFY studies. Value Health. 2024;27:607–13.

Mesa RA, Gotlib J, Gupta V, Catalano JV, Deininger MW, Shields AL, et al. Effect of ruxolitinib therapy on myelofibrosis-related symptoms and other patient-reported outcomes in COMFORT-I: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1285.

Hamasaki T, He Y, Evans SR. The DOOR is open: a web-based application for analyzing the Desirability of Outcome Ranking. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10:ofad500.439.

Walia A, Haslam A, Prasad V. FDA validation of surrogate endpoints in oncology: 2005-2022. J Cancer Policy. 2022;34:100364.

Klencke BJ, Donahue R, Gorsh B, Ellis C, Kawashima J, Strouse B. Anemia-related response end points in myelofibrosis clinical trials: current trends and need for renewed consensus. Future Oncol. 2024;20:703.

Barosi G, Tefferi A, Gangat N, Szuber N, Rambaldi A, Odenike O, et al. Methodological challenges in the development of endpoints for myelofibrosis clinical trials. Lancet Haematol. 2024;11:e383.

Howard-Anderson J, Hamasaki T, Dai W, Collyar D, Rubin D, Nambiar S, et al. Moving beyond mortality: development and application of a desirability of outcome ranking (DOOR) endpoint for hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;78:259.

Guglielmelli P, Maccari C, Sordi B, Balliu M, Atanasio A, Mannarelli C, et al. Phenotypic correlations of CALR mutation variant allele frequency in patients with myelofibrosis. Blood. Cancer J. 2023;13:21.

Guglielmelli P, Barosi G, Specchia G, Rambaldi A, Lo Coco F, Antonioli E, et al. Identification of patients with poorer survival in primary myelofibrosis based on the burden of JAV2V617F mutate allele. Blood. 2009;114:1477.

Oh ST, Verstovsek S, Gupta V, Platzbecker U, Devos T, Kiladjian J-J, et al. Changes in bone marrow fibrosis during momelotinib or ruxolitinib therapy do not correlate with efficacy outcomes in patients with myelofibrosis. eJHaem. 2024;5:105.

Ryou H, Sirinukunwattana K, Aberdeen A, Grindstaff G, Stolz BJ, Byrne H, et al. Continuous Indexing of Fibrosis (CIF): improving the assessment and classification of MPN patients. Leukemia. 2023;37:348.

Pemmaraju N, Garcia JS, Potluri J, Harb JG, Sun Y, Jung P, et al. Addition of navitoclax to ongoing ruxolitinib treatment in patients with myelofibrosis (REFINE): a post-hoc analysis of molecular biomarkers in a phase 2 study. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9:e434.

Marchetti M, Ghirardi A, Masciulli A, Carobbio A, Palandri F, Vianelli N, et al. Second cancers in MPN: a survival analysis from an international study. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:295.

Marchetti M, Salamanton-Garcìa J, El-Ashwah S, Verga L, Itri F, Racil Z, et al. Outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Ph-neg chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms: results from the EPICOVIDEHA registry. Ther Adv Hematol. 2023;14:20406207231154706.

Acknowledgements

European LeukemiaNet supported the project. Professor Evans Scott (Harvard University) kindly reviewed the typescript. RPG acknowledges support from the UK National Institute of Health Research (NIHR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: MM, TB, JM, and AMV. Data acquisition and analysis: MM. Interpretation of data: TB, JM, AMV, MM, AAL, AT, J-J-K, SK, SK, FP, AR, CH, RM, PB, JAA. Drafting typescript: MM, RPG, JM, AMV, RH, TB. Critical review of typescript for intellectual content: all the authors. Supervision: RPG, AMV, JM, TB, RH.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MM was a consultant to Gilead, Novartis, Roche, Menarini, and GSK. MM received support for meeting participation from AbbVie and Roche. MM is a member of The Methodology Team for Guideline Development of the Italian Society of Hematology and a PLOS-ONE Academic Associate Editor. AMV received speaker honoraria from Incyte, AbbVie, Novartis, BMS, AOP, ITF, and participated in Safety or Advisory Boards for Incyte, Novartis, and BMS. JM received grants from Incyte, Novartis, AbbVie, BMS, CTI/SOBI, Karyopharm, Geron, Kartos, and PharmaEssentia and consulting fees from Incyte, Novartis, AbbVie, BMS, CTI/SOBI, Karyopharm, Geron, Kartos, Roche, Mark, GSK, Disc, PharmEssentia, MorphoSys, and Keros. AAL received honoraria for lectures from AOP and GSK and consulting fees from AOP. PB received grants from Incyte, BMS, CTI/SOBI, Morphosys, Kartos, telios, Janssen, Geron, Ionis, Disc, Karyopharm, Sumitomo, Ajax, Blueprint, Cogent, and consulting fees from Incyte, BMS, CTI/SOBI, GSK, AbbVie, Morphosys, PharaEssentia, Ionis, Disc, Karyopharm, Sumitomo, Geron, Morphic, Jubilant, Keros, Ono, Raythera, Novartis, Blueprint, Cogent. RPG is a consultant to Antengene Biotech LLC; Medical Director, FFF Enterprises Inc.; A speaker for Janssen Pharma and Hengrui Pharma; Board of Directors: Russian Foundation for Cancer Research Support and Scientific Advisory Board, StemRad Ltd. CH received consulting fees from Sobi, Merck, GSK, OPNA Bio, Incyte, BMS, Alethiomics, CTI, Silence Therapeutics, Karyopharm, Galecto, Mennari Stemline, DISC, Keros, Morphosys, Novartis. CH also received honoraria for lectures from Novartis, GSK, Merck, Menarini Stemline, AOP, BMS, Incyte, Morphosys, and support for attending meetings from Novartis. CH disclaims her leadership role for MPN Voice and Blood Cancer UK. RH does not disclose any COI. JJK participated in Safety or Advisory Boards for Incyte and BMS and received support for meeting attendance from Novartis. JJK received honoraria as a speaker from AOP and PharmaEssenti and consulting fees from GSK, Novartis, and AbbVie. Gilead, Jazz, Omeros, Sanofi, Italfarmaco. SK received consulting fees from Novartis, BMS, Incyte /Ariad, AOP Pharma, Baxalta, CTI, Pfizer, Sanofi, Celgene, Shire, Janssen, Geron, Karthos, Sierra Oncology, Glaxo-Smith Kline (GSK), Imago Biosciences, AbbVie, MSD, iOMEDICO. SK also received speaker honoraria from Novartis, BMS, Pfizer, Incyte, Ariad, Shire, Roche, AOP Pharma, Janssen, Geron, Celgene, Karthos, AbbVie, iomedico, GSK, MSD, and payment for expert testimony from Novartis and GSK. SK received support for meeting attendance from Alexion, Novartis, BMS, Celgene, Incyte, Ariad, AOP Pharma, CTI, Pfizer, Sanofi, Janssen, Geron, Imago Biosciences, GSK, PharmaEssentia, Sierra, Oncology, AbbVie, iOMEDICO, and MSD. SK has a patent for a BET inhibitor drug for RWTH Aachen University. SK joined Safety or Advisory Boards for Pfizer, Incyte/Ariad, Novartis, AOP Pharma, BMS, Celgene, Geron, Janssen, CTI, Roche, Baxalta, Sanofi, MPN Hub, Sierra Oncology, Glaxo-Smith Kline, and AbbVie. SK is Chairman of the Hemostasis Working Party of German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO), Speaker of German Study Group of MPN (GSG-MPN), Member of Guidelines Committee of European Haematology Association (EHA), and Associate Editor for Hemasphere journal. RM did not disclose any COI. FP received honoraria for lectures from Novartis, Bristol-Myers, Squibb, Abbvie, GSK, Janssen, AOP Orphan, Novartis, Bristol-Myers, Squibb, AbbVie, GSK, Janssen, AOP Orphan, and Jazz. FP also participated in Safety Monitoring Boards or Advisory Boards for Novartis, Bristol-Myers, Squibb/ Celgene, GSK, AbbVie, AOP Orphan, Janssen, Sumitomo, and Kartos. AR participated in Safety Monitoring Boards or Advisory Boards for Amgen, Novartis, and Kite. AT did not disclose any COI. TB did not disclose any COI.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was not needed since patients’ data were not managed, nor tests or treatments performed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marchetti, M., Vannucchi, A.M., Mascarenhas, J.O. et al. European LeukemiaNet criteria for safety and efficacy evaluation of new drugs for myelofibrosis. Blood Cancer J. 15, 207 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01381-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01381-y