Abstract

There is currently no clear consensus on the standard of care for relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL) beyond third-line therapy, where both anti-CD19 CAR-T-cell therapy (CAR-T) and CD3×CD20 bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) have demonstrated efficacy. This study aimed to examine their efficacy and toxicity profiles. Relevant studies published between January 2010 and June 2025 were identified through major databases. Of 3960 records screened, 12 studies met the inclusion criteria—7 involving CAR-T and 5 involving BsAbs. The pooled overall response rate (ORR) and complete response rate (CRR) were 93% and 82% for CAR-T, compared with 82% and 67% for BsAbs (p = 0.0002 and p = 0.005, respectively). Among patients with POD24, the CRR was 75% for CAR-T and 69% for BsAbs (p = 0.56). This translated into improved progression-free survival (PFS) with CAR-T: 6-month, 1-year and 3-year PFS rates were 85%, 74% and 54%, respectively, compared with 74%, 62%, and 42% for BsAbs (p = 0.006, p = 0.002 and p = 0.009, respectively). A trend toward higher 3-year overall survival (OS) was observed with CAR-T (80%) versus BsAbs (73%) (p = 0.48). Grade ≥3 immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) occurred more frequently with CAR-T (8% vs. 0%, p = 0.04), whereas grade ≥3 infections were numerically higher with BsAbs (17% vs. 9%, p = 0.31). One-year non-relapse mortality (NRM) was similar between groups at 3%. Overall, CAR-T demonstrated potentially higher efficacy in this non-comparative meta-analysis, while the two therapies exhibited noticeable differences in toxicity profiles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) has an incidence of 20–25% worldwide and is the most common subtype of indolent B-cell lymphoma [1]. Despite its indolent nature, 15–20% of FL assume a more aggressive disease progression, particularly those with progression of disease within 24 months (POD24). This subpopulation of FL typically requires multiple lines of therapies, including autologous stem cell transplant [2]. Unfortunately, both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) decline markedly with each subsequent line of treatment. This was demonstrated by Batlevi et al., who reported a stepwise reduction in median PFS and OS with each progressive line of chemotherapy [3]. At the same time, a multicentre study from the USA reported considerable variability in the types of therapies used in third-line or later, with 2-year PFS of 40% and lymphoma remained the main cause of death (17% in 5 years) after a median follow-up of 71 months [4]. Both studies highlight the limitations of conventional immunochemotherapies in achieving and maintaining disease control.

The treatment paradigm of relapsed or refractory (R/R) FL has shifted remarkably since the introduction of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T), as well as bispecific antibody (BsAb), all of which have successfully demonstrated an unprecedentedly high metabolic complete response rate (CRR) in the third line (3L) or beyond (3L+) setting [5,6,7,8,9,10]. However, based on their single-arm Phase 2 trials, these treatment modalities have been associated with significant adverse events, particularly neurological toxicities such as immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), cytokine-release syndrome (CRS) and infective complications.

In the absence of Phase 3 randomised controlled trials comparing these two T-cell-mediated therapies, the clinical decision-making process in the 3L or beyond R/R FL setting remains challenging. While awaiting the availability of more Phase 3 clinical trials data [11], our group conducted this systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of all currently available Phase 1/2 CAR-T and BsAb trials in R/R FL as 3L+ treatment with the aim of comparing their relative strengths and weaknesses, focusing on their efficacy and safety profiles.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and study selection criteria

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) [12] and the Meta-Analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines [13] and registered on the PROSPERO database (Prospero no: CRD42024608398). A comprehensive systematic search of Medline/PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Library was conducted. To achieve maximum sensitivity for the search strategy, combinations of free text and medical subject heading were used e.g. For patient population, ‘lymphoma, follicular’[Mesh] OR ‘lymphoma, b-cell’[MeSH Terms], relapsed refractory [MeSH Terms] AND for intervention, ‘chimeric t cell receptor’ [MeSH Terms] OR ‘CAR-T’, ‘antibodies, bispecifics’[MeSH Terms]. Full search terms used are summarised in Table 1. The search was also expanded by reviewing the reference lists of initial studies included for further relevant articles to ensure a comprehensive search.

Eligibility criteria

Searches were conducted from 1 January 2010 to 30 June 2025, as clinical trials of CAR-T and BsAb started only after 2010. The study eligibility criteria were defined a priori. Population included: adult (≥18 years) subjects with FL; who had received ≥2 prior lines of therapy. Interventions of interest were anti-CD19 CAR-T therapy; and CD20xCD3 BsAb treatment. Prospective interventional clinical trials that evaluated the efficacy of CD20×CD3 BsAb or anti-CD19 CAR-T therapy for R/R FL were included. Phase 1 dose escalation studies used to determine the recommended Phase 2 dose were also included. Studies with the following characteristics were excluded: (1) Evaluated the therapy as first or second line; (2) Studied a paediatric population; (3) Assessed dual targeting or other targeting CAR-T or BsAb. Table 1 summarises the study eligibility criteria used.

Screening search results

The study selection process occurred in two phases. Level 1 screening: titles and abstracts of studies identified from the electronic database searches were double-screened in a blinded fashion by two researchers, independently and in parallel, to determine eligibility according to the eligibility criteria displayed in Table 1. Disagreements between any two research members were reviewed by a third reviewer for consensus. Level 2 screening: Full texts of studies selected in level 1 were retrieved and reviewed to determine eligibility in a similar manner as in level 1 screening. The final selected studies were identified for data extraction and further appraisal. The inclusion and exclusion processes were thoroughly documented, including completion of a PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1).

Data extraction and risk of bias appraisal

For studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, data were extracted by the research team (PLM, LXH, LCKN, TYC and MS) and tabulated to summarise key findings. Baseline data extracted from each study were: study characteristics (author and year of publication, study design, timing of study and location), patient and disease characteristics (including age, stage of disease, percentage of patients with POD24, double refractory disease, refractory to last line of treatment, FLIPI scores [14] and disease bulk, lines of chemotherapy given, percentage who had received prior hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or CAR-T (for the BsAb group)). Efficacy measurements of interest included: overall response rates (ORRs); complete remission rates (CRRs) [For BsAb trials, CRR rates in the CAR-T naïve population were also collected]; 1-year PFS; 1-year OS; and safety outcomes such as adverse events including grade ≥3, CRS, ICANS and infection. Data were extracted from full-text versions of studies, where available, or from conference abstracts summary by one reviewer and data were then quality-checked by a second reviewer. Discrepancies between the two investigators were resolved by discussion and consensus. Risk of bias in individual studies was evaluated independently by two reviewers (PLM and LCKN) using the cohort checklist of the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale (NOS) [15].

Data synthesis and analysis

Results of this systematic literature review were summarised qualitatively and quantitatively as appropriate. Although we had planned to calculate risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI), the current body of evidence did not find any comparative trials to perform such an analysis. Therefore, evidence from single-arm studies was summarised using descriptive summary statistics. When the demographics of the study populations and inclusion/exclusion criteria were relatively similar between the single-arm cohort studies, a meta-analysis of proportions (expressed as a percentage), with their 95% CI, was performed using the Review Manager (RevMan), version (8.1.1) for our analyses (available at revman.cochrane.org). To incorporate heterogeneity (anticipated among the included studies), transformed proportions were combined using DerSimonian-Laird random effects models.

In order to assess whether effect sizes were consistent across the included studies, heterogeneity was quantified. The test for heterogeneity was performed using the I2 statistic, which provides a magnitude of variability, where 0% indicates that any variability is due to chance, whilst higher I2 values (>50%) indicate increasing levels of unexplained variability. I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond to low, moderate and high degrees of heterogeneity, respectively. Differences between subgroups were calculated using the chi-square test, as reflected in the reported p values.

We carried out the outcome analyses, as far as possible, on an intention-to-treat basis, meaning we included all participants allocated to each group in the analyses, regardless of whether they received the allocated intervention or not. Missing data and drop-outs/attrition for each study were considered while evaluating the ‘Risk of bias’, and the extent to which the missing data could alter the results/conclusions of the review is discussed in this review [16].

Results

Literature search

A total of 3960 records were identified from database searches (Medline = 1197, Embase = 2415, The Cochrane Library = 348), of which 3459 were eligible for screening after removal of duplicates. Of these, 108 potentially eligible studies remained eligible for detailed review. Of these, 12 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in this review (CD19 CAR-T = 7; CD3xCD20 BsAb = 5). Details of the PRISMA inclusion/exclusion process are presented in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

This review did not identify any Phase III randomised controlled trials comparing the effect of CAR-T therapy versus BsAb in patients with R/R FL with a high risk of disease progression. Of the 12 trials, nine were Phase II single-arm studies (4 combination Phase I/II), two Phase I studies and one prospective case-series. A total of 795 patients were included in the analysis: 398 patients received CAR-T, 397 patients received BsAb, with the sample sizes of the studies ranging from 8 to 128 patients. CAR-T from the 7 clinical trials include: Tisagenlecleucel (Tisa-cel) (Fowler et al. [17], Dreyling et al. [6]), Axicabtagene ciloleucel (Axi-cel) (Jacobsen et al. [36], Neelapu et al. [5]), Lisocabtagene maraleucel (Liso-cel) (Morchhauser et al., 2024), Relmacabtagene autoleucel, CD19 CAR-T with a fixed CD4:CD8 ratio 1:1, utilising the 41BB co-stimulatory domain (later developed as Liso-cel) (Hirayama et al. [18]), CTL019 (later developed as Tisa-cel) (Schuster et al. [19], Chong et al. [20]) and the FMC63-derived single-chain variable fragment moiety (scFv) CD19-reactive CAR with a CD28 co-stimulatory receptor (Fried et al. [21]); BsAb trials include: two studies of Odronextamab (Bennerji et al. [22], Kim et al. [10]), one study of Epcoritamab (Linton et al. [9]) and two studies of Mosunetuzumab (Budde et al. [23] and Sehn et al. [8], Goto et al. [24]). Median age of patients ranged from 53 to 72 years old. Median follow-up ranged from 4 months to 42 months. Details of the included studies were summarised in Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment

Given the lack of quality assessment tools for single-arm trials, Risks of Bias assessment was evaluated using the cohort checklist of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) [15]. Key domains were assessed individually for each study, including: selection of the study groups and ascertainment of either the exposure or outcome of interest for the studies. Studies were then graded accordingly based on the NOS. This quality assessment is described in Table 3.

Efficacy outcomes

Response rates (RR)

All 12 included studies reported ORR and CRR. The pooled ORR was higher in patients treated with CAR-T therapy at 93% (95% CI: 88–97%) compared to 82% (95% CI: 78–86%) in patients treated with BsAb, p = 0.0002. The difference in treatment benefit was 11% (95% CI: 7–16%) in favour of CAR-T therapy. Similarly, more patients given CAR-T therapy achieved CRR at 82% (95% CI: 73–91%), compared to BsAb at 67% (95% CI: 61–73%), p = 0.005. CAR-T therapy demonstrated a 15% (95% CI: 9–21%) greater CRR benefit compared to the BsAb. However, when we examined the higher risk patient group who suffered progression within 24 months (POD24), the difference in treatment benefit reduced to only 6% (95% CI: 0–13%), p = 0.56 in which the pooled CRR for POD24 cohort from 4 trials was 75% (95% CI: 58–92%) for CAR-T compared to pooled estimates from 3 BsAb trials (69%; 95% CI: 61–77%) (Fig. 2A–C).

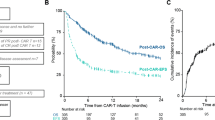

Progression-free survival (PFS)

There was significant heterogeneity among studies in terms of the time points used to assess PFS. All 12 studies reported 6-month PFS; however, not all trials reported beyond this period. At 6 months, the pooled PFS estimate was 85% (95% CI: 80–90%) in patients treated with CAR-T, compared to 74% (95% CI: 68–80%) in those given BsAb, p = 0.006. This translates to an 11% (95% CI: 5–17%) higher PFS with CAR-T compared to BsAb at 6 months. At 1 year (11 studies: 6 CAR-T, 5 BsAb), the pooled PFS rate remained higher when treated with CAR-T 74% (95% CI: 68–80%) versus 62% (95% CI: 57–66%), in patients given BsAb with a risk difference of 12% (5–18%), p = 0.002.

Fewer studies reported PFS at 2 years (8 studies: 4 each for CAR-T and BsAb). The evidence from these single-arm trials demonstrated that CAR-T pooled 2-year PFS was 62% (95% CI: 54–71%) compared to 47% (95% CI: 42–53%) in patients treated with BsAb. The difference in 2-year PFS was 15% (95% CI: 0.08–0.22%), p = 0.004. 3-year PFS was only reported in two CAR-T and three BsAb studies; the pooled estimates were 54% (95% CI: 47–60%) and 42% (95% CI: 36–48%), respectively (risk difference 12% (95% CI: 3–21%), p = 0.009 (Fig. 3A–D)).

Overall survival (OS)

Patients treated with CAR-T again demonstrated a potential benefit in OS than those treated with BsAb. However, compared to RR and PFS, this difference in OS was smaller. Pooled 6-month, 1-year, 2-year and 3-year OS for CAR-T compared to BsAb were 98% (95% CI: 96–100%) vs 90% (95% CI: 86–94%), p = 0.002; 94% (95% CI: 92–96%) vs 87% (95% CI: 81–94%), p = 0.05; 87% (95% CI: 83–91%) vs 76% (95% CI: 62–90%), p = 0.13; and 80% (95% CI: 74–85%) vs 73% (95% CI: 54–91%), p = 0.48, respectively. Notably, the number of studies contributing to OS analysis decreased with longer follow-up durations (Fig. 4A–D).

Toxicity outcomes

Grade ≥3 toxicities, including CRS, ICANS and infections, were assessed across studies. The pooled incidence of grade ≥3 CRS was low for both modalities: 3% (95% CI: 0–6%) for CAR-T and 4% (95% CI: 1–7%) for BsAb, p = 0.75. The pooled rate of grade ≥3 ICANS was notably higher in CAR-T studies at 8% (95% CI: 1–15%), compared to 0% (95% CI: 0–2%) in BsAb studies, p = 0.04. In contrast, CAR-T therapies demonstrated a numerically lower pooled rate of severe infections (grade ≥3) compared to BsAb [9% (95% CI: 4–15%) versus 17% (95% CI: 3–31%), p = 0.31]. One-year non-relapse mortality (NRM) was similar between groups, with a pooled rate of 3% (95% CI: 1–5%), p = 0.92 for both CAR-T and BsAb therapies (Fig. 5A–D).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of data from single-arm trials of CAR-T and BaAb trials demonstrates that CAR-T therapies may be more effective than BsAb in the third line and beyond setting for adult patients with R/R FL. Evidence from pooled analyses of non-comparative trials demonstrated that patients treated with CAR-T had higher ORR and CRR compared to those who received BsAb. In the high-risk POD24 subgroup, CAR-T-cell therapy’s benefit is less pronounced, with both CAR-T and BsAb demonstrating comparable efficacy, achieving CRRs of 75% and 69%, respectively, with p = 0.56. The higher ORR and CRR in patients treated with CAR-T translated to consistently higher PFS across time points, from 6 months to 3 years. However, OS were similar between the two treatment modalities.

While CAR-T-cell therapies achieved better ORR, CRR and PFS, on the other, hand they are also associated with higher rates of ICANS compared to BsAbs. This may be contributed to by the ZUMA-5 trial, which reported a significant event rate of 0.15 of severe (grade ≥3) ICANS. This has been postulated to be related to the use of the CD28 co-stimulatory domain in this product [25]. Additionally, some of the CAR-T studies included in our analysis were conducted during the early clinical development of CAR-T therapies, when management strategies for ICANS were still evolving and potentially suboptimal. Since then, several clinical practice guidelines have been developed to reduce the incidence of severe ICANS, such as the early prophylactic use of high-dose corticosteroids, e.g. dexamethasone and cytokine antagonists, e.g. anakinra [26, 27]. In contrast, severe ICANS was rarely observed with BsAb. As such, they may represent a safer treatment option for outpatient administration.

However, BsAb appear to be associated with potentially higher risk of severe infective complications, with higher rates of ≥ grade 3 infections reported compared to CAR-T therapy. This could possibly be attributed to prolonged B-cell suppression with BsAb, as they are typically administered over a longer period compared to CAR-T. The duration of BsAb therapy varies by agent and clinical response, ranging from 8 to 17 months with mosunetuzumab to continuous treatment approaches with agents like epcoritamab and odronextamab. Our findings are generally in agreement with a recent meta-analysis focusing specifically on the infective complications of BsAb and CAR-T [28], which also showed that both all-grade and ≥ grade 3 infections per patient-month were significantly higher in patients receiving BsAb compared to those treated with CAR-T. Moreover, continuous-treatment BsAb were associated with higher rates of ≥ grade 3 infections than fixed-duration ones.

In BCMA-targeted BsAb, preventive strategies such as vaccination and administration of intravenous immunoglobulin have been shown to help mitigate the risk of infections [29]. Furthermore, fixed-duration therapy, as seen with mosunetuzumab, may also reduce infective risk by allowing immune reconstitution after treatment cessation. A possible confounding factor that might have led to the increased infection rate reported in BsAb may be related to the timing of some BsAb trials - with many taking place during the early phases and peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Importantly, none of the toxicities discussed led to excessive NRM, with 1-year NRM rates remaining below 5% for both treatment modalities.

These findings in FL are similar to a previous meta-analysis comparing CAR-T and BsAb in the treatment of relapsed/refractory aggressive large B-cell lymphoma, which also demonstrated that CAR-T was superior in terms of efficacy, particularly in CRR and 1-year PFS [30]. However, in that study, the toxicity profile favoured BsAb, showing lower rates of ≥ grade 3 CRS, ICANS and infections compared to CAR-T therapy.

Despite the encouraging findings, several critical factors and limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, this study represents a secondary analysis based on published data from prospective single-arm trials. Consequently, the analysis is subject to heterogeneity in study designs and enroled patient populations. Due to the lack of individual patient data (IPD), propensity score matching could not be performed. Although efforts were made to minimise heterogeneity by restricting inclusion to studies evaluating third-line therapy and beyond, inherent differences among studies should still be acknowledged.

Secondly, due to significant heterogeneity within each treatment group, we were unable to conduct certain subgroup analysis beyond the CRR in the POD24 subgroup—one of the most frequently reported high-risk cohorts. However, there were slight differences among included studies on definition of POD24. (Summarised in Table 2) While 4 out of 5 of the BsAb included patients who had failed CAR-T, the outcomes of these patients were not reported separately, hence precluding subgroup analyses for this cohort. Given however these patients contributed a very small proportion of the overall trial population (≤5% for all except one study), it is unlikely they would confound or affect the overall findings of this meta-analysis. Additionally, as the reported median duration of follow-up varies across studies, with some studies having a relatively short follow-up, pooled analysis for 2-year and 3-year PFS and OS may not be fully representative of all studies. Given that FL is typically an indolent disease with a prolonged clinical course, a 3-year follow-up may be insufficient to detect differences in OS. Additionally, the availability of multiple subsequent therapies—including switching to CAR-T or BsAb not previously used, as well as targeted agents like tazemetostat and zanubrutinib—may further influence long-term outcomes [31, 32].

Thirdly, our analysis mainly focuses on efficacy and toxicity data between CAR-T and BsAb. Other important factors, such as logistics, frequency of clinic visits, total duration of active therapy and cost, were not compared here. Although important, these outcomes were not frequently reported in trials to allow for a systematic review and comparison. In general, CAR-T therapies involve complex logistics, including apheresis, manufacturing and potential inpatient care for acute toxicities, as well as post-treatment monitoring requirements such as proximity to treatment centres and driving restrictions. In contrast, BsAb, being off-the-shelf products, avoid many of these logistical challenges but require prolonged administration and frequent clinic visits.

Fourthly, a key consideration often under-reported in clinical trials is patient-reported outcomes and health-related quality of life, which were not reported in all the studies we included here. These factors may significantly influence patient preferences. A study led by the Lymphoma Epidemiology of Outcome Consortium found that patients with FL value a holistic and individualised approach to treatment that minimises side effects, fits their lifestyle and reduces overall treatment burden [33]. While both patients and physicians prioritise disease control and survival, patients are often more willing to trade some degree of efficacy for convenience, reduced toxicity and fewer monitoring visits [34, 35].

Finally, our study is unable to address the optimal sequencing of therapies, as data on PFS2 and OS2 were not available. It is likely that CAR-T and BsAb both serve important roles at different stages of FL management, rather than being mutually exclusive options. Ongoing clinical trials are evaluating both modalities in earlier lines of therapy, which may reshape future treatment sequencing.

In conclusion, this pooled analysis shows that CAR-T therapy could be potentially more effective and have longer durability of remission compared to BsAb in the third line and beyond setting, for adult patients with R/R FL. Toxicity profiles vary not only between the two modalities, and among the different agents within each category. Future comparative randomised controlled clinical trials are essential to determine the optimal sequencing and integration of these treatments in the evolving therapeutic landscape.

Data availability

For original data, please contact lawrence.ng.c.k@singhealth.com.sg.

References

Cerhan JR. Epidemiology of follicular lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2020;34:631–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2020.02.001.

Casulo C, Byrtek M, Dawson KL, Zhou X, Farber CM, Flowers CR, et al. Early relapse of follicular lymphoma after rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone defines patients at high risk for death: an analysis from the National LymphoCare Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2516–22. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7534.

Batlevi CL, Sha F, Alperovich A, Ni A, Smith K, Ying Z, et al. Follicular lymphoma in the modern era: survival, treatment outcomes, and identification of high-risk subgroups. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10:74. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-020-00340-z.

Casulo C, Larson MC, Lunde JJ, Habermann TM, Lossos IS, Wang Y, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes of patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma receiving three or more lines of systemic therapy (LEO CReWE): a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9:e289–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00033-3.

Neelapu SS, Chavez JC, Sehgal AR, Epperla N, Ulrickson M, Bachy E, et al. Three-year follow-up analysis of axicabtagene ciloleucel in relapsed/refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (ZUMA-5). Blood. 2024;143:496–506. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2023021243.

Dreyling M, Fowler NH, Dickinson M, Martinez-Lopez J, Kolstad A, Butler J, et al. Durable response after tisagenlecleucel in adults with relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma: ELARA trial update. Blood. 2024;143:1713–25. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2023021567.

Morschhauser F, Dahiya S, Palomba ML, Martin Garcia-Sancho A, Reguera Ortega JL, Kuruvilla J, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel in follicular lymphoma: the phase 2 TRANSCEND FL study. Nat Med. 2024;30:2199–207. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02986-9.

Sehn LH, Bartlett NL, Matasar MJ, Schuster SJ, Assouline SE, Giri P, et al. Long-term 3-year follow-up of mosunetuzumab in relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma after ≥2 prior therapies. Blood. 2025;145:708–19. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2024025454.

Linton KM, Vitolo U, Jurczak W, Lugtenburg PJ, Gyan E, Sureda A, et al. Epcoritamab monotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (EPCORE NHL-1): a phase 2 cohort of a single-arm, multicentre study. Lancet Haematol. 2024;11:e593–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(24)00166-2.

Kim TM, Taszner M, Novelli S, Cho SG, Villasboas JC, Merli M, et al. Safety and efficacy of odronextamab in patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2024;35:1039–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2024.08.2239.

Ng LCK, Casulo C. Current landscape of frontline and relapsed follicular lymphoma trials. Blood Neoplasia. 2025;100131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bneo.2025.100131.

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160.

Brooke BS, Schwartz TA, Pawlik TM. MOOSE Reporting Guidelines for Meta-analyses of Observational Studies. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:787–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0522.

Solal-Céligny P, Roy P, Colombat P, White J, Armitage JO, Arranz-Saez R, et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood. 2004;104:1258–65. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2003-12-4434.

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies in meta-analysis. Available: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 2 November 2024.

Shapiro H, Shodimu V, Webb N. SA109 quality assessment tools for single-arm studies: a rapid review. Value Health. 2024;27:S635–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2024.10.3190.

Fowler NH, Dickinson M, Dreyling M, Martinez-Lopez J, Kolstad A, Butler J, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: the phase 2 ELARA trial. Nat Med. 2022;28:325–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01622-0.

Hirayama AV, Gauthier J, Hay KA, Voutsinas JM, Wu Q, Pender BS, et al. High rate of durable complete remission in follicular lymphoma after CD19 CAR-T cell immunotherapy. Blood. 2019;134:636–40. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019000905.

Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA, Nasta SD, Mato AR, Anak Ö, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells in refractory B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2545–54. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1708566.

Chong EA, Ruella M, Schuster SJ, Lymphoma Program Investigators at the University of Pennsylvania. Five-year outcomes for refractory B-cell lymphomas with CAR T-cell therapy. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:673–4. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2030164.

Fried S, Shkury E, Itzhaki O, Sdayoor I, Yerushalmi R, Shem-Tov N, et al. A. Point-of-care anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2023;64:1956–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2023.2246611.

Bannerji R, Arnason JE, Advani RH, Brown JR, Allan JN, Ansell SM, et al. Odronextamab, a human CD20×CD3 bispecific antibody in patients with CD20-positive B-cell malignancies (ELM-1): results from the relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma cohort in a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9:e327–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00072-2.

Budde LE, Sehn LH, Matasar M, Schuster SJ, Assouline S, Giri P, et al. Safety and efficacy of mosunetuzumab, a bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:1055–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00335-7.

Goto H, Kumode T, Mishima Y, Kataoka K, Ogawa Y, Kanemura N, et al. Efficacy and safety of mosunetuzumab monotherapy for Japanese patients with relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma: FLMOON-1. Int J Clin Oncol. 2025;30:389–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-024-02662-5.

Schubert ML, Schmitt M, Wang L, Ramos CA, Jordan K, Müller-Tidow C, et al. Side-effect management of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:34–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.10.478.

Gazeau N, Liang EC, Wu QV, Voutsinas JM, Barba P, Iacoboni G, et al. Anakinra for refractory cytokine release syndrome or immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome after chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. Transplant Cell Ther. 2023;29:430–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtct.2023.04.001.

Oluwole OO, Bouabdallah K, Muñoz J, De Guibert S, Vose JM, Bartlett NL, et al. Prophylactic corticosteroid use in patients receiving axicabtagene ciloleucel for large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2021;194:690–700. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.17527.

van Besien HJ, Easwar N, Demetres M, Pasciolla M, Shore T, Leonard JP, et al. Comparative infection risk in CAR T vs bispecific antibodies in B cell lymphoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Adv. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2025016291.

Mohan M, Szabo A, Cheruvalath H, Clennon A, Bhatlapenumarthi V, Patwari A, et al. Effect of Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) Supplementation on infection-free survival in recipients of BCMA-directed bispecific antibody therapy for multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2025;15:74. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01282-0.

Kim J, Cho J, Lee MH, Yoon SE, Kim WS, Kim SJ. CAR T cells vs bispecific antibody as third- or later-line large B-cell lymphoma therapy: a meta-analysis. Blood. 2024;144:629–38. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2023023419.

Morschhauser F, Tilly H, Chaidos A, McKay P, Phillips T, Assouline S, et al. Tazemetostat for patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1433–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30441-1.

Zinzani PL, Mayer J, Flowers CR, Bijou F, De Oliveira AC, Song Y, et al. ROSEWOOD: a Phase II randomized study of zanubrutinib plus obinutuzumab versus obinutuzumab monotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:5107–17. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.00775.

Tsang M, Durani U, Day JR, Larson MC, Holets M, Yost KJ, et al. Understanding the patient perspective on treatment preferences for follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2024;144:7598.

Thomas C, Marsh K, Trapali M, Krucien N, Worth G, Cockrum P, et al. Preferences of patients and physicians in the United States for relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma treatments. Cancer Med. 2024;13:e70177. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.70177.

Gaballa S, Xue M, Totev TI, Meng Y, Challagulla S, Chen Z, et al. Patient medication preferences in follicular lymphoma (FL) in the United States (USA): a discrete-choice experiment (DCE). Blood. 2024;144:3655.

Jacobson CA, Chavez JC, Sehgal AR, William BM, Munoz J, Salles G, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel in relapsed or refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (ZUMA-5): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:91–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00591-X.

Ying Z, Zou D, Yang H, Wu J, Guo Y, Li W, et al. Preliminary efficacy and safety of Relmacabtagene autoleucel (Carteyva) in adults with relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma in China: a Phase I/II clinical trial. Am J Hematol. 2022;97:E436–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26711.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LCKN and MLMP conceptualised and designed the study. LCKN, XHL, YCT, KLW, JCYC, WWLC, VWTL, EWST, EHLC, MS and MLMP screened the literature identified using the search protocol. LCKN, XHL, YCT, MS and MLMP abstracted data from selected studies. LCKN, XHL, YCT, MS and MLMP drafted the initial manuscript, and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MLMP: study PI for Regeneron and Genmab trials, advisory steering committee and speaker bureau for Regeneron, Travel support by Kite/GiLEAD.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ng, L.C.K., Lee, X.H., Tan, Y.C. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: CAR-T vs bispecific antibody as third or later-line therapy for follicular lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 16, 17 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01439-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01439-x