Abstract

In newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM), current risk stratification relies on cytogenetics and disease burden, but emerging immune parameters may refine prognosis. While a higher non-clonal plasma cell fraction (NCPF) predicts favorable outcomes in smoldering myeloma, its relevance in NDMM remains unexplored. We retrospectively analyzed 798 patients with NDMM where baseline bone marrow aspirates were tested to determine the NCPF, defined as the proportion of non-clonal plasma cells among total plasma cells. An NCPF ≥ 5% defined the NCPF-Enriched group. NCPF-High was observed in 124 patients (15.5% of all cohort). Compared to NCPF-Low, NCPF-Enriched patients had lower overall bone marrow plasma cell burden (median 20% vs. 50%, p < 0.0001), higher rates of hyperdiploidy (71% vs. 59%, p = 0.025), and similar cytogenetic risk. Six-year overall survival (OS) was significantly higher in NCPF-Enriched (70.3% vs. 56.5%, p = 0.0096), with independent prognostic value in multivariable analysis (HR 0.64, p = 0.03). Progression-free survival was also superior (HR 0.69, p = 0.006) in the NCPF-Enriched cohort in the setting of comparable treatment approaches. A higher non-clonal plasma cell fraction at diagnosis is independently associated with improved outcomes in NDMM, highlighting its potential as a novel immune prognostic biomarker warranting further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a clonal plasma cell neoplasm marked by considerable biological and clinical heterogeneity [1,2,3]. Despite therapeutic advances, including proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs, monoclonal antibodies, and cellular therapies, MM remains largely incurable, and long-term disease control remains elusive for a significant subset of patients [4, 5]. Current risk stratification such as the second revision of the International Staging System (R2-ISS) and the International Myeloma Society (IMS)/International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) risk stratification in NDMM relies heavily on cytogenetic abnormalities detected via interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), including del(17p), t(4;14), t(14;16)/t(14;20), 1q gain/amplification, and del(1p32), as well as markers of disease burden [3, 6]. However, these models do not account for the residual normal plasma cells, which can influence tumor behavior and host response [7]. In smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM), a clonal plasma cell fraction ≥95% is associated with rapid progression, whereas a higher non-clonal plasma cell fraction (NCPF) is linked to more indolent disease [8]. Despite these insights in SMM, the prognostic relevance of NCPF in newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) remains largely unexplored in the context of other contemporary established high-risk features.

There are several hypotheses postulated to support the improved prognosis in patients with higher normal/non-clonal plasma cell fraction. A higher NCPF may reflect a better preserved immune surveillance capable of restraining malignant plasma cell expansion and/or reduced infection risk due to maintained humoral immunity, or a reflection of lower tumor burden [9, 10]. When compared to plasma cells from healthy donors, polyclonal plasma cells from patients multiple myeloma demonstrate an upregulation in autophagy and interferon-related pathways, and these alterations correlated with immunoparesis [11]. In the current study, we retrospectively analyzed a large cohort of NDMM patients with available bone marrow flow cytometry data to investigate the clinical and prognostic significance of NCPF. We hypothesized that patients with a higher NCPF at diagnosis can be associated with favorable biological features and improved survival outcomes.

Methods

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The Mayo Clinic Intitutional Review Board Approval was obtained for conducting the study (25-000605). Individual informed consent was obtained per institutional requirements and guidelines.

Study cohort and statistical considerations

We included patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) between 01/01/2013 and 01/31/2023. Non-clonal plasma cell fraction, defined as the percentage of non-clonal plasma cells among total plasma cells, was measured using MFC on bone marrow aspirates collected at the time of initial diagnosis at the same institution before initiation of myeloma-directed therapy. Flow cytometric immunophenotyping was performed using the following antibodies: CD19, CD38, CD45, CD138, cytoplasmic kappa and lambda immunoglobulin, and DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) as previously described [12]. The plasma cell clonality was determined through demonstrating CD38 and CD138 positivity, absence of CD19/CD45 expression, immunoglobulin light chain restriction, and/or ploidy difference by DAPI staining. An NCPF of ≥5% was considered as NCPF-Enriched and we hypothesized this to be associated with better prognosis. High-risk cytogenetic abnormalities (HRCA) by FISH were defined as follows: presence of deletion 17p (del17p), t(4;14), t(14;16), t(14;20), 1q21 gain/amplification, and deletion 1p. An adaptation of the 2024 IMS/IMWG classification was utilized for risk stratification [without the TP53 mutation data and biallelic del(1p)] and the R2-ISS were applied to the current cohort. Immunoparesis was defined as having one uninvolved immunoglobilins (IgG, IgA and IgM) below the lower limit of laboratory normal and severe immunoparesis was defined as having two or more uninvolved immunoglobulins below the lower limit of laboratory normal. Categorical variables were compared using chi square test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using the non-parametric Wilcoxon test. All time-to-event analyses were performed using the Kaplan Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards analyses were performed to assess the independent prognostic impact of the NCPF-Enriched fraction. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

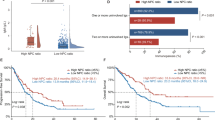

We included 798 patients with data available for NCPF estimation. The median follow-up for the entire cohort was 6 years and the estimated median overall survival (OS) was 8.2 years (95% CI: 5.6-6.4 years). The median NCPF for the entire cohort was 0.4% (interquartile range: 0.11–1.8%). As a continuous variable, a higher NCPF was associated with an improved survival [HR 0.98; 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.97-9.99, p = 0.02]. Out of this cohort, 124 patients (15.5%) had a NCPF of ≥5% (NPCF-Enriched), which was chosen as the cutoff for the study cohort based on comparable survival between NCPF < 1% (6-year OS 58%) and NCPF 1.0-4.99% cohorts (6-year OS: 61%) and significantly improved survival for the NCPF ≥ 5% cohort (6-year OS: 70.3%, Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, the 5% cutoff has been used in prior studies in the setting of smoldering myeloma and shown to have prognositic value [8]. Baseline characteristics of the patients in the two cohorts are depicted in Table 1. Patients with a NCPF-Enriched had a significantly lower median bone marrow plasma cell infiltration (20% vs. 50%, p < 0.0001). The NCPF-Enriched cohort was also enriched for hyperdiploid cytogenetics (71.1% vs. 58.8%, p = 0.025) and had a lower prevalence of the t(11;14) translocation (14.3% vs. 24.3%, p = 0.02). Notably, the rate of two or more high-risk cytogenetics (11.8% vs. 13.2%, p = 0.76) and the IMS/IMWG high-risk designation (25.2% vs. 25.5%, p = 0.94) were comparable between the NCPF-Enriched and NCPF-Low cohorts, respectively. No significant differences were observed in age, sex, elevated S-phase or treatment intensity between the NCPF Enriched and NCPF-Low groups (Table 1).

Patients within the NCPF-Enriched cohort had a lower likelihood of having immunoparesis. The rates of immunoparesis (with one uninvolved immunoglobulin being suppressed) were also significantly lower in NCPF-Enriched cohort (56.7% vs. 92.2%, OR 0.11, p < 0.0001), Fig. 1. Similarly, within the NCPF-Enriched cohort, a significantly lower proportion of patients had two or more uninvolved immunoglobulins suppressed (23.7%) compared to the NCPF-Low cohort (73.2%) [odds ratio (OR) of 0.12, P < 0.0001]. Notably, patients with immunoparesis demonstrated a trend toward an inferior OS [HR 1.41 (0.96–2.1), p = 0.07] compared to patients without immunoparesis (Supplementary Fig. 2A).

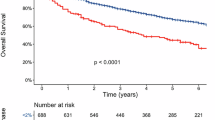

The 6-year overall survival (OS) rate was significantly higher in patients with a high non-clonal plasma cell fraction (NCPF-Enriched), at 70.3% (95% CI: 62–79%), compared to 56.5% (95% CI: 52.2–61%) in the NCPF-Low cohort, Fig. 2. The median OS was not reached in the NCPF-Enriched group, whereas it was 7.6 years in the NCPF-Low group. This translated into a statistically significant survival benefit for the NCPF-Enriched group [p = 0.0096; hazard ratio (HR) 0.64, 95% CI: 0.46–0.90]. On univariate analysis, age ≥75 years at diagnosis, IMS/IMWG high-risk cytogenetic status, elevated S-phase fraction (≥2%), bone marrow plasma cell infiltration ≥50%, and reduced renal function (eGFR <45 mL/min) were prognostic for OS (Supplementary Table 1). When included in a multivariable model, NCPF-Enriched remained independently associated with improved overall survival [HR 0.64, 95% CI: 0.43–0.96; p = 0.03], Fig. 3. These results were consistent after adjusting for treatment parameters (Supplementary Table 2) as well immunoparesis (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Substituting the IMS/IMWG high-risk designation by incorporating ≥2 HRCAs within the multivariable model (to account for the absence of the sequencing data for a complete assessment of the IMS/IMWG high-risk desgination) demonstrated consistent results for the prognostic impact of NCPF (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Treatment details and progression-free survival (PFS) event information were available for 753 (94.4%) patients. The median PFS with frontline therapy was 4.2 years (95% CI: 2.7–7 years) for the NCPF-Enriched cohort compared to 2.6 years (2.3–2.9 years) for the NCPF-Low cohort [HR 0.69 (95% CI: 0.53–0.9), p = 0.006], Fig. 4. The induction, transplant and maintenance strategies were comparable in the two cohorts (Table 1). After adjusting for factors predictive of PFS on a univariate analysis including factors including age ≥75 years at diagnosis, IMS/IMWG high-risk cytogenetic status, elevated S-phase fraction ( ≥ 2%), bone marrow plasma cell infiltration ≥50% and reduced renal function (eGFR <45 mL/min) (Supplementary Table 3), the NCPF-Enriched status was independently associated with an improved PFS [HR 0.72 (95% CI: 0.53–0.99, p = 0.049; Supplementary Table 4). Even when adjusted for type of induction (doublet, triplet or quadruplet), ASCT or not and maintenance (received or not), the NCPF-Enriched designation was associated with an improved PFS [HR 0.62 (95% CI: 0.4–0.86, p = 0.003].

Discussion

In this cohort of patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma with well-anotated cytogenetic profiles and proliferative signatures, we demonstrate that a higher non-clonal plasma cell fraction (NCPF ≥ 5%) at diagnosis is independently associated with favorable clinical and biological features, including lower marrow infiltration, lower rates of severe immunoparesis, and improved survival. These findings support the hypothesis that residual non-clonal plasma cells, measurable via baseline multiparameter flow cytometry, may serve as a marker of biologically indolent disease.

The observed association between high NCPF and reduced BMPC infiltrate underscores the inverse relationship between residual normal plasma cells and disease burden. A higher NCPF may indicate not only a lower malignant burden but also a protective coexistence of functional repertoire of plasma cells. A NCPF-Enriched state was associated with significantly lower rates of immunoparesis, particularly severe immunoparesis (23.7% vs. 73.2%). Immunoparesis is a known negative prognostic factor in MM, thought to reflect both direct tumor-induced immune suppression and broader microenvironmental dysregulation [8, 11, 13]. The independent prognostic value of NCPF was retained even after adjusting for the immunoparesis status and its strong yet independent prognostic value suggests that NCPF may integrate broader aspects of immune fitness beyond what the traditional serum markers capture.

Our study further shows that patients with NCPF-Enriched status were more likely to exhibit hyperdiploidy, a cytogenetic feature generally associated with favorable prognosis. Interestingly, the rates of t(11;14), considered to be prognostically neutral, were lower in patients with NCPF-enriched cohort, further highlighting their distinct clinical and pathologic features compared to other cytogenetic abnormalities [14, 15]. The biologic rationale for higher rates of t(11;14) in the NCPF-Low is intriguing and needs further study. Notably, NCPF remained an independent predictor of both OS and PFS in multivariable models adjusting for known high-risk features. This finding confirms that NCPF captures prognostic information not entirely accounted for by existing risk stratification systems that are focused on tumor cell characteristics [3]. The 6-year OS rate of 70.3% in the NCPF-Enriched group, compared to 56.5% in the NCPF-Low group, is clinically meaningful and consistent with survival differences seen with other recognized prognostic biomarkers.

These findings suggest that NCPF may serve as a surrogate for preserved immunologic architecture within the marrow, echoing the concept that immune function plays a pivotal role in controlling disease progression in MM [16,17,18]. This is further supported by recent single-cell studies showing that residual normal plasma cells and intact immune subsets in the marrow correlate with deeper responses and longer remissions [11, 16, 17]. Thus, NCPF could potentially be used in future as an immune-microenvironmental marker for risk stratification, alongside existing genetic and laboratory-based models.

From a translational perspective, assessing NCPF is a technically feasible and cost-effective addition to routine flow cytometry panels already employed at MM diagnosis [12]. Multiparameter flow cytometry enables precise immunophenotypic distinction between clonal and non-clonal plasma cells using surface and cytoplasmic markers and immunoglobulin light chain restriction [19,20,21,22]. Incorporating the presence of normal plasma cells into risk assessment frameworks could provide a more comprehensive understanding of disease biology and therapeutic responsiveness, particularly in the era of immunotherapy. These approaches allow for quantification of the non-clonal component of plasma cells and may provide a surrogate for immune microenvironment integrity. It requires no additional reagents or processing and can be standardized across laboratories. The clinical relevance of NCPF also opens the door to potential interventional strategies aimed at preserving or restoring normal plasma cell and B-cell function, which may be particularly relevant in the era of immunotherapy. For example, vaccine responses and infection risk stratification could be guided by NCPF status, given its correlation with immunoparesis.

Our study has certain limitations. First, as a retrospective single-institution analysis, it is subject to inherent biases, including referral and selection bias. Second, although our flow cytometry protocols were standardized, inter-laboratory reproducibility of NCPF measurement remains to be tested. Third, while this MFC based approach is easily reproducibly, there is a possibility that the lack of B-cell receptor sequencing and single-cell level approach can misclassify a small proportion of clonal and non-clonal plasma cells. Fourth, the absence of the sequencing data for a complete assessment of the IMS/IMWG high-risk desgination is a limitation of the study. However, the consistency of the results when using ≥2 HRCAs in the multivariable model provides further reinforcement of the prognostic implications of the NCPF-enriched cohort. The impact of prior vaccination status on the NCPF fraction is also unknown. Lastly, study cohort was restricted to patients enrolled until January 2023, resulting in a small fraction of patients treated with quadruplet induction therapy. These findings merit confirmation in a predominantly CD38 antibody-based quadruplet induction therapy.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that a high non-clonal plasma cell fraction at diagnosis is independently associated with favorable clinicopathologic features and superior survival outcomes in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. NCPF represents a novel and clinically accessible biomarker that reflects preserved marrow immunoarchitecture and offers complementary prognostic value to established cytogenetic and laboratory-based risk factors. These findings warrant external validation and suggest a role for NCPF in future models of risk stratification, particularly those incorporating immune and microenvironmental parameters.

Data availability

De-identified data utilized for the analysis in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhan F, Huang Y, Colla S, Stewart JP, Hanamura I, Gupta S, et al. The molecular classification of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:2020–8.

Skerget S, Penaherrera D, Chari A, Jagannath S, Siegel DS, Vij R, et al. Comprehensive molecular profiling of multiple myeloma identifies refined copy number and expression subtypes. Nat Genet. 2024;56:1878–89.

Zanwar S, Rajkumar SV. Current risk stratification and staging of multiple myeloma and related clonal plasma cell disorders. Leukemia. 2025.

Ravi P, Kumar SK, Cerhan JR, Maurer MJ, Dingli D, Ansell SM, et al. Defining cure in multiple myeloma: a comparative study of outcomes of young individuals with myeloma and curable hematologic malignancies. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8:26.

Jagannath S, Martin TG, Lin Y, Cohen AD, Raje N, Htut M, et al. Long-Term (≥5-Year) remission and survival after treatment with ciltacabtagene autoleucel in CARTITUDE-1 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:2766–71.

Avet-Loiseau H, Davies FE, Samur MK, Corre J, D’Agostino M, Kaiser MF, et al. International myeloma society/international myeloma working group consensus recommendations on the definition of high-risk multiple myeloma. J ClinOncol.2025: Jco2401893.

Paiva B, Vidriales M-B, Mateo G, Pérez JJ, Montalbán MA, Sureda A, et al. The persistence of immunophenotypically normal residual bone marrow plasma cells at diagnosis identifies a good prognostic subgroup of symptomatic multiple myeloma patients. Blood. 2009;114:4369–72.

Pérez-Persona E, Vidriales MB, Mateo G, García-Sanz R, Mateos MV, de Coca AG, et al. New criteria to identify risk of progression in monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance and smoldering multiple myeloma based on multiparameter flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow plasma cells. Blood. 2007;110:2586–92.

Ghosh T, Gonsalves WI, Jevremovic D, Dispenzieri A, Dingli D, Timm MM, et al. The prognostic significance of polyclonal bone marrow plasma cells in patients with relapsing multiple myeloma. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:E507–E512.

Paiva B, Vídriales MB, Rosiñol L, Martínez-López J, Mateos MV, Ocio EM, et al. A multiparameter flow cytometry immunophenotypic algorithm for the identification of newly diagnosed symptomatic myeloma with an MGUS-like signature and long-term disease control. Leukemia. 2013;27:2056–61.

Da Vià MC, Lazzaroni F, Matera A, Marella A, Maeda A, De Magistris C, et al. Aberrant single-cell phenotype and clinical implications of genotypically defined polyclonal plasma cells in myeloma. Blood. 2025;145:3124–38.

Zanwar S, Jevremovic D, Kapoor P, Olteanu H, Buadi F, Horna P, et al. Clonal plasma cell proportion in the synthetic phase identifies a unique high-risk cohort in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2025;15:20.

Ledergor G, Weiner A, Zada M, Wang S-Y, Cohen YC, Gatt ME, et al. Single cell dissection of plasma cell heterogeneity in symptomatic and asymptomatic myeloma. Nat Med. 2018;24:1867–76.

Kitadate A, Terao T, Narita K, Ikeda S, Takahashi Y, Tsushima T, et al. Multiple myeloma with t(11;14)-associated immature phenotype has lower CD38 expression and higher BCL2 dependence. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:3645–54.

Robillard N, Avet-Loiseau H, Garand R, Moreau P, Pineau D, Rapp MJ, et al. CD20 is associated with a small mature plasma cell morphology and t(11;14) in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2003;102:1070–1.

Zavidij O, Haradhvala NJ, Mouhieddine TH, Sklavenitis-Pistofidis R, Cai S, Reidy M, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals compromised immune microenvironment in precursor stages of multiple myeloma. Nat Cancer. 2020;1:493–506.

Maura F, Boyle EM, Coffey D, Maclachlan K, Gagler D, Diamond B, et al. Genomic and immune signatures predict clinical outcome in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma treated with immunotherapy regimens. Nat Cancer. 2023;4:1660–74.

Dang M, Wang R, Lee HC, Patel KK, Becnel MR, Han G, et al. Single cell clonotypic and transcriptional evolution of multiple myeloma precursor disease. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:1032–47.e1034.

Paiva B, Vidriales MB, Pérez JJ, Mateo G, Montalbán MA, Mateos MV, et al. Multiparameter flow cytometry quantification of bone marrow plasma cells at diagnosis provides more prognostic information than morphological assessment in myeloma patients. Haematologica. 2009;94:1599–602.

Sanoja-Flores L, Flores-Montero J, Garcés JJ, Paiva B, Puig N, García-Mateo A, et al. Next generation flow for minimally-invasive blood characterization of MGUS and multiple myeloma at diagnosis based on circulating tumor plasma cells (CTPC). Blood Cancer J. 2018;8:117.

Medina A, Puig N, Flores-Montero J, Jimenez C, Sarasquete ME, Garcia-Alvarez M, et al. Comparison of next-generation sequencing (NGS) and next-generation flow (NGF) for minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10:108.

Paino T, Paiva B, Sayagues JM, Mota I, Carvalheiro T, Corchete LA, et al. Phenotypic identification of subclones in multiple myeloma with different chemoresistant, cytogenetic and clonogenic potential. Leukemia. 2015;29:1186–94.

Funding

PK: Loxo Pharmaceuticals: Research Funding; Kite: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees; Oncopeptides: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees; CVS Caremark: Consultancy; Karyopharm: Research Funding; GlaxoSmithKline: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; Pharmacyclics: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees; AbbVie: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; Janssen: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees; Mustang Bio: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees; Sanofi: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; BeiGene: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; Ichnos: Research Funding; Angitia Bio: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees; X4 Pharmaceuticals: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees; Keosys: Consultancy; Bristol Myers Squibb: Research Funding; Regeneron: Research Funding; Amgen: Research Funding. Cook: Geron Corp: Other: Held $600 Geron Stock for one week and sold without profit. AD: Janssen: Research Funding; Alexion: Consultancy, Research Funding; Takeda: Consultancy, Research Funding; HaemaloiX: Research Funding; Alnylam: Research Funding; BMS: Consultancy, Research Funding; Pfizer: Research Funding. DD: Genentech: Consultancy; Sorrento: Consultancy, Honoraria; Janssen: Consultancy, Honoraria; Novartis: Consultancy, Honoraria; Regeneron: Consultancy, Honoraria; K36 Therapeutics: ResearchFunding; BMS: Consultancy, Honoraria; Sanofi: Consultancy, Honoraria; MSD: Consultancy, Honoraria; Apellis: Consultancy, Honoraria, ResearchFunding; Alexion: Consultancy, Honoraria. TK: Novartis: Research Funding; Pfizer: Research Funding. NL: Checkpoint Therapeutics: Current holder of stock options in a privately held company; AbbVie: Current holder of stock options in a privately held company. Lin: Pfizer: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees; Janssen: Consultancy, Research Funding; Caribou: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees; Bristol-Myers Squibb: Consultancy, Research Funding; Sanofi: Consultancy; NexImmune: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees; Genentech: Consultancy; Legend: Consultancy; Celgene: Consultancy, Research Funding; Regeneron: Consultancy. EM: Protego: Consultancy. YLH: GSK: Honoraria; MultiMedia Medical, LLC: Consultancy; Shield Therapeutics: Honoraria; Janssen: Honoraria; Pfizer: Other: Consulting fee located to Mayo Research fund. SK: Celgene: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; Roche: Research Funding; Merck: Research Funding; Takeda: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; KITE: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; MedImmune/AstraZeneca: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; Adaptive: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; Oncopeptides: Other: Independent review committee participation; Abbvie: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; Janssen: Membership on an entity’s Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; Novartis: Research Funding; Sanofi: Research Funding. Rest of the authors do not have any relevant disclosures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SZ and SK conceived the project, performed the primary analysis and wrote the first draft; DJ, HO, PH, GO analyzed the flow cytometry data; SZ and SK; DJ, PK, HO, FB, PH, WG, JS, GO, NA, MB, JC, AD, DD, SD, MAG, TK, NL, YL, EM, MS, MW, RW, RAK, SVR critically reviewed the manuscript, suggested edits, and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript draft for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zanwar, S., Jevremovic, D., Kapoor, P. et al. Elevated non-clonal bone marrow plasma cell fraction at diagnosis is associated with improved outcomes in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 16, 20 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01449-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01449-9