Abstract

Prognosis for patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) has been improving. Short-term survival information, such as crude survival rates that consider deaths immediately after the transplantation, may not be sufficiently useful for assessing long-term survival. Using the data of the Japanese HCT registry, the net survival rate of patients who survived for a given period was determined according to age, disease, and type of transplant. We included a total of 41,716 patients who received their first allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation between 1991 and 2015. For each disease, age group, graft source subcategory, net survival was calculated using the Pohar-Perme method, and 5-year conditional net survival (CS) was calculated. Ten-year net survivals of total patient cohort were 41.5% and 47.4% for males and females, respectively. Except for myelodysplastic syndrome, multiple myeloma, and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, 5-year CS for 5-year transplant survivors exceeded 90%. CS was especially high for aplastic anemia, of which was over 100% for children and younger adults receiving cord blood, suggesting that these patients have similar longevity to an equivalent group from the general population. These findings provide useful information for long-term survival, and can serve as benchmark for comparisons among registries, including other cancers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) is performed to treat various malignant and non-malignant hematological diseases. Transplant outcome has improved over the past decades, and resulted in increasing numbers of long-term transplant survivors [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Although many transplant survivors live healthy lives, the delayed effects of transplantation as well as increased risk of secondary cancers continue to affect the clinical courses of transplant survivors [8].

In the field of cancer studies, population-based descriptive studies are a commonly used methodology [9,10,11,12]. Cancer patients may die from causes other than the studied cancer; therefore, the methodology used in population-based descriptive studies removes risks of dying from other causes from the assessment and estimates the proportion of patients dying from direct or indirect consequences of cancer [13, 14]. Transplant recipients may die of the causes other than original disease, which are commonly grouped as non-relapse mortality. It is assumed that a significant portion of these deaths are associated with the transplantation process. However, this assumption may not be valid for individuals who survive for an extended period, as they could potentially face mortality from causes unrelated to the transplant [15]. Few population-based studies have been performed in transplant settings [7, 16,17,18]; however, population-based descriptive epidemiology studies employing methodologies such as net survival may also provide useful information for patients receiving transplants similarly to cancer survival studies while excluding the risks of dying from causes other than cancer or transplantation.

Previous studies have investigated the prognosis of patients who would receive a future transplant. Statistical time analyses in the majority of previous transplant outcome studies are generally performed using the time of transplantation as the time origin [19]. However, information on survival trends obtained from those studies are limited for patients who have already survived more than a couple of years post-transplant [20]. Conditional survival (CS) is defined as the probability that a person will survive an additional number of years if they have already survived a specific number of years. This metric offers an updated prediction of survival throughout the course of the disease [21, 22]. For long-term transplant survivors, CS may provide more relevant information compared to survival measured from the time of transplantation. Meanwhile, the graft source differently affects the course of the transplant and survivals due to the factors such as delayed engraftment, risk of infection, acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GvHD). Although many studies have reported differences in transplant outcomes between bone marrow, peripheral blood (PB), and cord blood (CB) for various diseases [23,24,25,26], these studies were generally analyzed from the time of transplant. Information of long-term survival probabilities after the 2-year period when most deaths occur are scarce.

This study aimed to evaluate the outcomes of transplant survivors from year 0 to year 5 after transplant. We also aimed to provide an overview of long-term survival of children and adults who had already survived up to 5 years from the time of transplant, by investigating different graft sources for different diseases using a population-based methodology incorporating net-survival analysis [27] and CS using net-survival probabilities.

Methods

Patients and data

Data were obtained from the Japanese Data Center for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (JDCHCT) [28,29,30,31,32]. Survival information for patients were annually updated at each transplant center, and the final annual update cycle of this dataset was performed during the period from June to October, 2016.

Patients included in the analysis were patients who received first allogeneic HCT between 1991 and 2015. Diseases consisted of: acute myeloid leukemia (AML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), malignant lymphoma (ML), multiple myeloma (MM), and aplastic anemia (AA). For age group analysis, children were defined as those 15 years old and under, younger adults as those aged 16 years to 59 years old, and older adults as those aged 60 years and over. Patients with unknown sex were excluded. In total, 41,716 patients were eligible. The study was approved by Nagoya University Ethics Committee (approval no. 2018-0150) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients provided informed consent for the use of clinical information.

Outcomes and statistical analysis

The main outcomes of the study were 10-year net survival and the conditional 5-year net survival at 5 years after transplantation, which is defined as the net probability of surviving a further 5 years given that the patient had already survived for 5 years. In cancer studies, net survival provides the cumulative probability for cancer patients to survive their cancer up to an elapsed point in time from the starting time, such as the time of diagnosis or time of transplantation, after controlling for risks of death from other background mortalities (see Supplementary Materials for further details) [10, 13, 14, 33]. Survival was defined as the time after transplantation or landmark time until death from any cause, with surviving patients censored at the time of last follow up. Conditional 5-year net survival by disease and age groups were calculated for patients who had already survived 5 years after transplantation. The Pohar-Perme method was applied for the estimation of net survival. The background mortality of the patients was calculated using the complete Japanese population life tables by birth year, age, and sex. These tables are published annually by Center for Cancer Control and Information Services, National Cancer Center, which is based on information provided by the Statistics and Information Department of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan [34, 35].

For each disease, graft source, and age group sub-analysis, conditional 5-year net survival was further estimated annually for patients who had survived up to 5 years after the transplant. Upper and lower boundaries of 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to compare the survivals of each graft source. For younger adults, AML, ALL, ATL, CML, MDS, MM, ML, and AA were analyzed; however, we only analyzed AML, ALL, MDS, ML, and AA for children, and AML, ALL, MDS, ML, and ATL for older adults, due to the limited number of patients with other diseases. Overall survival (OS) and conditional OS were estimated using Kaplan–Meier method (as described in the Supplementary Materials). Causes of death and completeness of follow-up [36, 37] are also summarized in the Supplementary materials. Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp, TX) was used for analyses.

Results

Characteristics of patients and transplantation outcomes

The characteristics of the patients, their diseases, and transplants received are shown in Table 1. The median age of the recipients was 41 years. AML (39%), ALL (22%), MDS (11%), and ML (10%) were the most frequent indications for transplantation. Bone marrow transplantation accounted for 60%, PB accounted for 19%, and CB was used in 20%. Detailed patient characteristics according to graft source and age groups are shown in Table S1. Completeness of follow-up at 5 years after transplantation for patients who received a transplantation between 1991 and May 2011 was 92.9%.

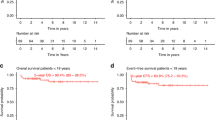

Net survival and conditional net survival for each disease

We calculated net survival by sex and disease. Five-year net survivals were 45.5% (95% CI, 44.9–46.2) and 50.8% (50.0–51.6), and 10-year net survivals were 41.5% (40.7–42.2) and 47.4% (46.6–48.3), for males and females respectively (Fig. 1a). Ten-year net survival estimates for each disease were relatively high for AA (78.1% [76.2–80.1]), and relatively low for ATL (27.6% [24.9–30.4]) and MM (21.1% [15.6–26.6]) (Table 2 and Fig. 1b). Net survival of CML, ALL, MDS, ML, and AML ranged intermediately.

Five-year CS at 5 years after transplantation by disease and age group is shown in Table 2. For the all-age and younger adult cohorts, 5-year CS of 5-year transplant survivors was relatively low for MM compared to other diseases (77.9% [95% CI, 65.5–90.3] and 76.6% [63.4–89.8], respectively). For children, 5-year CS of 5-year transplant survivors with AML, ALL, MDS, ML, and AA were relatively high with point estimates above 90%.

Conditional net survival of each graft source

Five-year conditional net survival by disease and age categories is shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Corresponding point estimates and 95% CIs are shown in Table S2. The impact of age on each disease is also illustrated for AML, ALL, MDS, ML, AA, and ATL by graft source and diseases in Fig. S1, using the same point estimates.

Five-year conditional net survivals of: (a) all ages and (b) younger adult patients at year 0 to year 5 after the transplant. Five-year conditional survival CS (t = 5 | X) was defined as the probability of surviving an additional number of years (t = 5), conditional on survival of (X) years where X = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. For each disease, changes of 5-year conditional net survivals over time are illustrated yearly to compare the results among different graft sources.

Five-year conditional net survivals of: (a) children and (b) older adults at year 0 to year 5 after the transplant. Changes in 5-year conditional net survival are compared between different graft sources for the age sub-groups using the methodology described in Fig. 2.

AML

Considering the whole patient cohort, 5-year CS of PB was lower than BM from year 0 to year 5 and lower than CB from year 1 to year 3. Five-year CS of CB was lower than BM at year 0, but trends of CS for CB became similar to BM in the following years and were higher than PB from year 1 to year 3 (Fig. 2a and Table S2A). Trends of younger adults were similar to those of the all-age cohort. Five-year CS of PB was also lower than BM from year 0 to year 4 and lower than CB from year 1 to year 3. Five-year CS of CB was lower than BM at year 0 and higher than PB from year 1 to year 3 (Fig. 2b and Table S2B). For children, 5-year CS of PB with AML tended to be lower than BM only at year 0 (Fig. 3a and Table S2C). For older adults, 5-year CS of BM tended to be higher than PB at year 0 and year 5, and 5-year CS of PB was lower than CB only at year 4 (Fig. 3b and Table S2D).

ALL

For the whole patient cohort, 5-year CS of PB was lower than BM and CB from year 0 to year 2 (Fig. 2a and Table S2A). For younger adults, 5-year CS of PB tended to be lower than BM at year 0 and year 1, and was also lower than CB at year 1 (Fig. 2b and Table S2B). For children, 5-year CS of PB tended to be lower than BM at year 0 and year 1 and lower than CB only at year 0 (Fig. 3a and Table S2C). For older adults, trends were not different among different sources (Fig. 3b and Table S2D).

MDS

For all-ages cohort, 5-year CS of PB was lower than BM from year 0 to year 3, and CS of CB was lower than BM at year 0 (Fig. 2a and Table S2A). For younger adults, 5-year CS of CB was lower than BM only at year 0 (Fig. 2b and Table S2B). For older adults, 5-year CS of PB was lower than BM only at year 0 (Fig. 3b and Table S2D).

ML

For whole patient cohort, 5-year CS of PB and CB was lower than BM at year 0, and CS of PB was lower than CB at year 1 (Fig. 2a and Table S2A). For younger adults, 5-year CS of CB and PB were lower than BM only at year 0 (Fig. 2b and Table S2B). For children, 5-year CS of PB was lower than BM and CB at year 0 (Fig. 3a and Table S2B).

AA

For whole patient cohort, 5-year CS of PB was lower than BM from year 0 to year 5 and CS of CB was lower than BM only at year 0 (Fig. 2a and Table S2A). For younger adults, 5-year CS of PB was lower than BM from year 0 to year 2 and at year 4 and year 5, and CS of CB was lower than BM at year 0 (Fig. 2b and Table S2B). For children, 5-year CS of CB was lower than BM only at year 0 (Fig. 3a and Table S2C).

CML

For whole patient cohort, 5-year CS of CB was lower than BM only at year 0 (Fig. 2a and Table S2A). Sub analysis of CML was performed only for younger adults, and 5-year CS of CB was lower than BM at year 0 and year 1 (Fig. 2b and Table S2B).

MM

For the whole patient cohort, 5-year CS of CB was lower than BM and PB at year 0 (Fig. 2a and Table S2A). Sub analysis was performed for younger adults, and 5-year CS was not different among sources (Fig. 2b and Table S2B).

ATL

For whole patient cohort, 5-year CS of CB was lower than BM and PB at year 0 (Fig. 2a and Table S2A). As the number of patients were limited, sub analysis was performed only for younger and older adults. For younger adults, 5-year CS of CB was lower than BM and PB at year 0 (Fig. 2a and Table S2A). For older adults, 5-year CS of CB was lower than BM at year 0 (Fig. 2b and Table S2B).

Conditional OS using Kaplan–Meier method

Point estimates of 5-year conditional OS by diseases and age categories using Kaplan–Meier method are shown in Table S3. Survival trends were similar to those of conditional net survival. Point estimates of survival were comparatively lower than those of net survival.

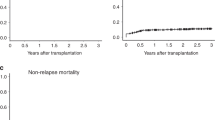

Causes of death

Figure S2 summarizes the proportion of each cause of death category. Over time, the percentage of patients who died from secondary malignancy or post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders, organ failure increased after transplantation. On the other hand, the contribution of relapse as a cause of death decreased after 3 years post-transplantation. The proportion of deaths classified as “cause of death unknown” increased in the later years after transplant.

Discussion

In this study, Japanese transplant registry data were analyzed to investigate long-term survival, utilizing the method used in population-based descriptive epidemiology studies. Five-year conditional net survival of children and younger adults with AA who had survived several years after the transplantation was nearly and exceeded 100% except for PB in younger adults, indicating that these patients had a similar chance of survival compared to the general population. On the other hand, 5-year conditional net survival of younger adults with MM receiving BM remained at 69% after 5 years survival, suggesting that some patients had recurrent disease. Furthermore, net survival of female patients was continuously higher than that of the male patients.

Differences in graft source continuously had an impact on 5-year CS through 5 years of transplantation for certain diseases. In previous studies, increased chronic GvHD in PB graft recipients with AA has been reported compared to BM among younger patients and adults [38, 39]. Increased chronic GvHD in PB could have continuously affect the survivals of the long-term survivors with AA. A previous study from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research reported superior overall and GvHD, relapse-free survival of AML receiving BM grafts compared to PB in well-matched unrelated donor transplant [40]. The current study suggested extended effect of graft source on survival of the recipients with AML who had already survived for 5 years. Long-term outcomes of CB were favorable in certain indications such as younger and older adults with leukemia. Ethnic differences in CB outcomes, particularly in relation to GvHD, have been reported in a collaborative study between European and Japanese populations [41].

In this study, we used net survival to estimate conditional survival for two reasons. First, although the registry captures causes of death reported by the physicians, causes of death are sometimes reported as either unknown or others; moreover, some causes of death are not clear during follow-up [15]. Second, causes of death that are major long-term transplant complications, such as cancer and cardiovascular or respiratory infection, are also the main causes of death among Japanese or other general populations [42, 43]. These causes would be difficult to be categorized as the causes of or not directly related to the transplant. Since introduction of the method that are used in population-based descriptive epidemiology removes death other than that caused by the baseline disease or transplant-related causes, we aimed to investigate survival while excluding potential causes unrelated to the transplant or disease using this method.

We did not perform statistical hypothesis testing to compare the outcomes of different graft sources, as this study was exploratory research and to avoid the multiple testing problems. We analyzed the data by referring to the general population to see survival trends in different transplant sources by observing 95% CIs. Statistical analysis using observed survival rates with Kaplan–Meier method could be generally useful for comparison of factors related to survival within the transplant cohort. In this study, the trends of conditional survival within different grafts were comparable between conditional survivals using net-survival methods and Kaplan–Meier method (Tables S2 and S3).

Unlike prospective clinical studies, the transplant registry collects real world data; thus, the accuracy of data remains a limitation of the present study especially for assessing long-term survival of patients due to the loss of follow-up, which is a common limitation of using registry data. Second, this study included patients who underwent transplantation over 30 years ago. The impact of these patients on the outcomes remains uncertain, given the improvements in transplant outcomes in the past decade. Third, the analysis did not consider donor type for sub-analysis. Unrelated PB donors became available from the JMDP only after 2010, and the cumulative number of long-term survivors is still limited. Preliminary analysis suggests that conditional net survivals of related and unrelated BM recipients were comparable at later years after transplantation (result not shown).

In this study, we performed analysis of overall transplant patients, adapting methods used in population-based descriptive epidemiology. As few population-based studies have been performed in transplant settings [16], the results of this study can serve as a benchmark of survival for future studies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions that it exceeds the scope of the recipient/donor’s consent for research use in the registry but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with permission of the JSTCT/JDCHCT.

References

Bhatia S, Dai C, Landier W, Hageman L, Wu J, Schlichting E, et al. Trends in late mortality and life expectancy after allogeneic blood or marrow transplantation over 4 decades: a blood or marrow transplant survivor study report. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:1626–34.

Tanaka Y, Kurosawa S, Tajima K, Tanaka T, Ito R, Inoue Y, et al. Analysis of non-relapse mortality and causes of death over 15 years following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:553–9.

Konuma T, Mizuno S, Kondo T, Arai Y, Uchida N, Takahashi S, et al. Improved trends in survival and engraftment after single cord blood transplantation for adult acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12:81.

Yanada M, Masuko M, Mori J, Aoki J, Mizuno S, Fukuda T, et al. Patients with acute myeloid leukemia undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: trends in survival during the past two decades. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019;54:578–86.

Konuma T, Itonaga H, Ishiyama K, Hamamura A, Uchida N, Ozawa Y, et al. Progress in survival following three decades of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for myelodysplastic syndrome: a real-world registry study in Japan. Am J Hematol. 2023;98:E68–71.

Shouval R, Fein JA, Labopin M, Kroger N, Duarte RF, Bader P, et al. Outcomes of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation from HLA-matched and alternative donors: a European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation registry retrospective analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6:e573–84.

Ohbiki M, Ito Y, Inamoto Y, Miyamura K, Uchida N, Fukuda T, et al. Improved long-term net survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with hematologic malignancies over two decades. Transpl Cell Ther. 2023;29:768.e761–10.

Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1813–26.

Hori M, Matsuda T, Shibata A, Katanoda K, Sobue T, Nishimoto H, et al. Cancer incidence and incidence rates in Japan in 2009: a study of 32 population-based cancer registries for the Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan (MCIJ) project. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2015;45:884–91.

Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, Harewood R, Matz M, Niksic M, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391:1023–75.

Ito Y, Miyashiro I, Ito H, Hosono S, Chihara D, Nakata-Yamada K, et al. Long-term survival and conditional survival of cancer patients in Japan using population-based cancer registry data. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1480–6.

Okuyama A, Shibata A, Nishimoto H. Critical points for interpreting patients’ survival rate using cancer registries: a literature review. J Epidemiol. 2018;28:61–6.

Pohar Perme M, Esteve J, Rachet B. Analysing population-based cancer survival—settling the controversies. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:933.

Roche L, Danieli C, Belot A, Grosclaude P, Bouvier AM, Velten M, et al. Cancer net survival on registry data: use of the new unbiased Pohar-Perme estimator and magnitude of the bias with the classical methods. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:2359–69.

Atsuta Y, Hirakawa A, Nakasone H, Kurosawa S, Oshima K, Sakai R, et al. Late mortality and causes of death among long-term survivors after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:1702–9.

Kliman D, Nivison-Smith I, Gottlieb D, Hamad N, Kerridge I, Purtill D, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients surviving at least 2 years from transplant have survival rates approaching population levels in the modern era of transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26:1711–8.

Vanderwalde AM, Sun CL, Laddaran L, Francisco L, Armenian S, Berano-Teh J, et al. Conditional survival and cause-specific mortality after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 2013;27:1139–45.

Smeland KB, Kiserud CE, Lauritzsen GF, Fagerli UM, Falk RS, Fluge O, et al. Conditional survival and excess mortality after high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation for adult refractory or relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma in Norway. Haematologica. 2015;100:e240–3.

Klein JP, Rizzo JD, Zhang MJ, Keiding N. Statistical methods for the analysis and presentation of the results of bone marrow transplants. Part I: unadjusted analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:909–15.

Wingard JR, Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, Wang Z, Sobocinski KA, Jacobsohn D, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2230–9.

Assouline S, Li S, Gisselbrecht C, Fogarty P, Hay A, van den Neste E, et al. The conditional survival analysis of relapsed DLBCL after autologous transplant: a subgroup analysis of LY.12 and CORAL. Blood Adv. 2020;4:2011–7.

Abdallah NH, Smith AN, Geyer S, Binder M, Greipp PT, Kapoor P, et al. Conditional survival in multiple myeloma and impact of prognostic factors over time. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13:78.

Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, Waller EK, Weisdorf DJ, Wingard JR, et al. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1487–96.

Jo T, Arai Y, Kondo T, Mizuno S, Hirabayashi S, Inamoto Y, et al. Advantages of peripheral blood stem cells from unrelated donors versus bone marrow transplants in outcomes of adult acute myeloid leukemia patients. Cytotherapy. 2022;24:1013–25.

Kuwatsuka Y, Kanda J, Yamazaki H, Mori T, Miyamura K, Kako S, et al. A comparison of outcomes for cord blood transplantation and unrelated bone marrow transplantation in adult aplastic anemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:1836–43.

Smith AR, Wagner JE. Alternative haematopoietic stem cell sources for transplantation: place of umbilical cord blood. Br J Haematol. 2009;147:246–61.

Nagamine CML, Goulart BNG, Ziegelmann PK. Net survival in survival analyses for patients with cancer: a scoping review. Cancers. 2022;14:3304.

Atsuta Y. Introduction of transplant registry unified management program 2 (TRUMP2): scripts for TRUMP data analyses, part I (variables other than HLA-related data). Int J Hematol. 2016;103:3–10.

Kanda J. Scripts for TRUMP data analyses. Part II (HLA-related data): statistical analyses specific for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2016;103:11–19.

Kuwatsuka Y. Quality control and assurance in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation data registries in Japan and other countries. Int J Hematol. 2016;103:20–24.

Atsuta Y, Suzuki R, Yoshimi A, Gondo H, Tanaka J, Hiraoka A, et al. Unification of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation registries in Japan and establishment of the TRUMP System. Int J Hematol. 2007;86:269–74.

Atsuta Y. [The Japanese Transplant Registry Unified Management Program (TRUMP((R))): current issues and the future]. [Rinsho ketsueki] Jpn J Clin Hematol. 2020;61:387–91.

Ssenyonga, Stiller N, Nakata KC, Shalkow J, Redmond S, Bulliard JL, et al. Worldwide trends in population-based survival for children, adolescents, and young adults diagnosed with leukaemia, by subtype, during 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual data from 258 cancer registries in 61 countries. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6:409–31.

Perme MP, Stare J, Esteve J. On estimation in relative survival. Biometrics. 2012;68:113–20.

National Cancer Center. Cancer Registry and Statistics, Cancer Information Service, National Cancer Center, Japan. Cohort Life Table. 2018. https://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/qa_words/cohort01.html.

Clark TG, Altman DG, De Stavola BL. Quantification of the completeness of follow-up. Lancet. 2002;359:1309–10.

Snowden JA, Saccardi R, Orchard K, Ljungman P, Duarte RF, Labopin M, et al. Benchmarking of survival outcomes following haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a review of existing processes and the introduction of an international system from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and the Joint Accreditation Committee of ISCT and EBMT (JACIE). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55:681–94.

Schrezenmeier H, Passweg JR, Marsh JC, Bacigalupo A, Bredeson CN, Bullorsky E, et al. Worse outcome and more chronic GVHD with peripheral blood progenitor cells than bone marrow in HLA-matched sibling donor transplants for young patients with severe acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2007;110:1397–400.

Bacigalupo A, Socie G, Schrezenmeier H, Tichelli A, Locasciulli A, Fuehrer M, et al. Bone marrow versus peripheral blood as the stem cell source for sibling transplants in acquired aplastic anemia: survival advantage for bone marrow in all age groups. Haematologica. 2012;97:1142–8.

Alousi A, Wang T, Hemmer MT, Spellman SR, Arora M, Couriel DR, et al. Peripheral blood versus bone marrow from unrelated donors: bone marrow allografts have improved long-term overall and graft-versus-host disease-free, relapse-free survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:270–8.

Kanda J, Hayashi H, Ruggeri A, Kimura F, Volt F, Takahashi S, et al. The impact of GVHD on outcomes after adult single cord blood transplantation in European and Japanese populations. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2022;57:57–64.

Tsugane S. Why has Japan become the world’s most long-lived country: insights from a food and nutrition perspective. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75:921–8.

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–128.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the physicians and staff at the transplant centers for providing clinical data to the registry. They also thank the staff at the JDCHCT for data management. This study was funded in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 17K08911 and 22K10360 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YK, HI, KT, TK, FK, JK, YA and KM designed the research and contributed to critical review of the manuscript. YK, HI, YA and KM analyzed data, YK performed statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the other authors contributed to data collection. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuwatsuka, Y., Ito, H., Tabuchi, K. et al. Trends in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation survival using population-based descriptive epidemiology method: analysis of national transplant registry data. Bone Marrow Transplant 59, 1295–1301 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-024-02326-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-024-02326-y