Abstract

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is the most frequent autoimmune disease (AD) treated with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). There are no prospective trials comparing the most used conditioning regimens, BEAM/Anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) and cyclophosphamide (CYC)/ATG. Herein, we report a retrospective analysis of the EBMT database aimed to assess their risk/benefit ratio. We included 1114 MS patients who were conditioned with either BEAM/ATG or CYC/ATG. Neutrophil engraftment in BEAM/ATG- and CYC/ATG-treated patients occurred at a median time of 11 and 10 days after HSCT (p = 0.079). Overall, 2.0% of patients conditioned with BEAM/ATG and 1.0% with CYC/ATG died within 100 days from HSCT (p = 0.19). Overall, the incidence of NEDA (No-Evidence of Disease Activity) failure in BEAM/ATG and CYC/ATG at 5 years was 42.3% (95% CI: 36.3–48.8%) and 44.1% (95% CI: 30.8–60.1%), respectively (p = 0.081). No statistically significant differences between the two treatments [HR = 0.90 (95% CI = 0.61; 1.34), p = 0.60] were confirmed, when adjusting for disease type, disability at baseline and year of transplant. A clear difference between the regimens is lacking, both in terms of toxicity and efficacy, in this large population. Type of disease (relapsing/remitting vs progressive) is still the major determinant of neurological outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is the most frequent autoimmune disease (AD) treated with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Starting from 1995 [1, 2] more than 2000 patients underwent the procedure and were reported to the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) registry, with a constant increasing trend in the last 10 years [3].

Increasing evidence support the use of autologous HSCT as highly effective therapeutic strategy for treatment-resistant inflammatory types of MS [4,5,6,7,8] in the relapsing-remitting phase [9]. According to the EBMT and the European Committee for treatment and research in multiple sclerosis (ECTRIMS) guidelines, highly active relapsing-remitting MS who have failed high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies (HE-DMT) is recommended as a standard care indication for HSCT [9,10,11]. This gradual shift to a major predominance of relapsing remitting over progressive forms [12, 13], including more patients in earlier inflammatory phases of the disease, was also supported by the EBMT data [9]. Therefore, patient selection plays a key role in providing the best risk/benefit ratio of the procedure.

In the last decade better outcomes have been obtained in MS patients with autologous HSCT, owing to the growing experience of both neurologists and hematologists in selecting the most appropriate patients to transplant, paralleled by advances in conditioning and support regimens. Freedom from inflammatory activity and maintenance immunosuppression is typically achieved for several years, and potentially permanently [14]. Importantly, autologous HSCT seems to offer clear advantage in terms of NEDA (no evidence of disease activity), showing rates of 66–93% compared with alemtuzumab, natalizumab or ocrelizumab [9]. Recent EBMT data reported 100-day transplant-related mortality (TRM) of 1.1%, 3-year TRM of 1.5%, relapse incidence of 34.4%, progression-free survival of 64%, and an overall survival of 95.5% [13, 15]. Despite the recent pandemic, the non-relapse mortality (NRM) remains stable at 1% (95% confidence interval, CI: 0.5–1.9) from 2015 through 2020 [3, 15].

A variety of conditioning regimens have been used in HSCT in autoimmune diseases and the EBMT have previously grouped regimens according to intensity [8, 16]. Whilst a minority of patients have received ‘low’ intensity regimens (such as high dose cyclophosphamide alone) or ‘high intensity’ regimens (containing high dose busulfan or total body irradiation), the vast majority of patients with MS have received ‘intermediate intensity’ regimens, based upon a combination of intensive chemotherapy and anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG). Up to 2013, most European patients with MS were conditioned with the ‘intermediate intensity’ conditioning regimen, BEAM (BCNU 300 mg/m2 on day -6, cytosine arabinoside, 200 mg/m2 and etoposide 200 mg/m2 day -5 to day -2, melphalan 140 mg/m2 day -1) plus ATG [7]. In more recent years, another ‘intermediate’ intensity regimen, cyclophosphamide usually at 200 mg/kg (CYC) and ATG, was successfully adopted and predominated in the following years [17]. In a phase III randomized clinical trial, the CYC (total dose 200 mg/kg) and rabbit ATG (total dose 6 mg/kg) showed a pronounced decrease in disease progression events as compared to approved DMTs [5].

As such, both regimens are included in the guidelines and recommendations from the EBMT Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP) [9]. Intensity of conditioning regimen results in different toxicity and, in the oncological setting, in different efficacy. A retrospective study from Sweden [18] has recently compared efficacy and safety of these regimens in 174 patients affected by relapsing-remitting MS. The NEDA at 5 years was 81% (CI 68–96%) with BEAM/ATG and 71% (CI 63–80%) with CYC/ATG (p = 0.29). Severe adverse events and prolonged hospitalization were more common with BEAM/ATG. However, there are no larger studies or prospective trials comparing these two regimens.

We report here an observational retrospective analysis of the EBMT database aimed to compare the effectiveness, safety and tolerability of the two regimens.

Methods

Study design and data source

This study is a retrospective multicenter study analyzing EBMT registry data, aiming to compare the safety and efficacy of the most used conditioning regimens (BEAM/ATG or CYC/ATG), in MS patients receiving autologous HSCT in centers reporting to the EBMT registry. The study was approved by the ADWP, and we extracted registry data on patients affected by MS who had been treated with autologous HSCT from 1995 to 2019 in EBMT centers (99 centers / 27 countries). Centers were invited to participate in a specific data collection for neurological data. Additional information was collected using a specific questionnaire (one section for hematologists including data on early transplant-related complications and one section for neurologists dedicated to collect MS data). Given the registry-based nature of this study, data were reported by centers on a voluntary basis.

Patient eligibility

The following inclusion criteria have been considered: diagnosis of MS according to the revised McDonald’s criteria [19]; availability of a detailed MS clinical history, including disability progression and relapse rate in the 2 years before the HSCT; availability of information about previous DMTs administered, patients aged 18 or more at time of transplant, first HSCT, and availability of a clinical follow-up, including regular neurological assessment and MRI scans. Enrolment in clinical trial, e.g. MIST [5], was an exclusion criterion for this analysis.

Endpoints and definitions

The primary study objective was to provide data about safety and efficacy of the two conditioning regimens in MS. Secondary study objectives were: early infectious and non-infectious complications (within 100 days after HSCT), fertility and pregnancy. In addition, data about post-transplant re-vaccinations given to patients with MS have been collected.

Primary endpoint was time to fail NEDA (No-Evidence of Disease Activity) [20, 21], consisting of the following features: (1) no relapses, (2) no disability progression measured by Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [22], and (3) no magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) activity (new or enlarging T2 lesions or Gd-enhancing lesions). Patients have been stratified according to major clinical variables, including time from diagnosis, previous treatments, MS disease course, age and baseline level of disability.

Statistical methods

Results were reported as N (%), mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) depending on the distribution of the variables. Characteristics were compared between the two groups using t-test or Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier estimator was used to estimate survival functions and log-rank test was employed to compare survival curves between the two groups (BEAM/ATG vs CYC/ATG). Univariable and multivariable Cox regression models were performed to study NEDA failure, adjusting for MS type, EDSS at baseline and year of transplant. All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software Stata (v.18; StataCorp); p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

We included 1114 MS patients from the EBMT database, who were conditioned with either BEAM/ATG (n = 442) or CYC/ATG (n = 672). Patients and HSCT characteristics are described in Table 1. The main characteristics of the BEAM/ATG- treated patients, as compared to CYC/ATG-treated patients, were greater disease duration at HSCT, higher numbers of progressive MS, worse EDSS and more lines of previous DMTs. Treatment epochs also differed, with the majority of BEAM/ATG- treatment before 2016 and the opposite for CYC/ATG. On patients alive, median follow up is 1.4 years in the CYC/ATG group and 4.6 years in the BEAM/ATG group. CD34 selection was adopted only in a minority of cases (n = 13; 2%).

Engraftment and mortality

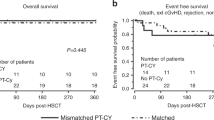

Complete data about engraftment and 100-days mortality were available in 1056 and 1103 patients respectively. Neutrophil engraftment (Fig. 1) occurred in 98.8% (n = 426) of BEAM/ATG- treated patients and in 99.38% (n = 638) of CYC/ATG-treated patients, at a median time of 11 (95% CI: 11; 11) and 10 (95%CI: 10; 11) days after HSCT respectively (log-rank test: p = 0.079). Nine out 442 [2.04%; 2/9 before 2000, 5/9 between 2000 and 2009, 2/9 between 2010 and 2019; median (range) time to death: 23 days (4–61)] patients conditioned with BEAM/ATG and 7 out 672 [1.04%; 1/7 between 2000 and 2009, 6/7 between 2010 and 2019; median (range) time to death: 2 days (1-90)] with CYC/ATG died within 100 days from HSCT, without significant differences among the two strategies (log-rank test: p = 0.19; Supplementary Fig. 1). Most deaths after HCT occur as a result of infections (n = 4), cardiac toxicity (n = 3), bleeding (n = 2), MS progression (n = 1), or other acute or subacute toxicities of HSCT (n = 6).

Efficacy

Overall, 19 centers from 11 countries participated in the collection for neurological data. Exhaustive MS data about the primary endpoint (time to fail NEDA) were available from 615 patients (295 received BEAM/ATG, 320 CYC/ATG; Supplementary Table 1), treated with HSCT between 1995 and 2018. The Kaplan-Meier estimate of NEDA failure in BEAM/ATG and CYC/ATG at 5 years (Fig. 2) was 42.3% (95% CI: 36.3–48.8%) and 44.1% (95% CI: 31.0–60.1%), respectively [HR = 0.75 (95% CI = 0.55; 1.04), p = 0.082]. No statistically significant differences between the two treatments [HR = 0.90 (95% CI = 0.61; 1.34), p = 0.604] were confirmed, when adjusting for disease type (progressive vs relapsing), Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) at baseline and year of transplant (Supplementary Figure 2). At 10 years (Fig. 3) the Kaplan-Meier estimate of NEDA failure was 51.5% (44.9%-58.4%). The Kaplan-Meier estimate of NEDA failure is significantly affected by MS type (Fig. 4), showing worse outcome in progressive MS as compared to relapsing-remitting MS [HR = 2.18 (1.61; 2.95), p < 0.001]. At 5-year the proportion of NEDA patients was 68% (95% CI = 61%; 74%) in the relapsing/remitting MS group and 45% (95% CI = 36%; 53%) in the progressive MS group (log-rank test: p < 0.001).

Early complications and secondary endpoints

We collected additional data on early complications and secondary endpoints through a specific study questionnaire in 653 patients, who were conditioned with either BEAM/ATG (n = 306/653; 47%) or CYC/ATG (n = 347/653; 53%).

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation was reported in 68/313 MS patients (21.7%; n = 39/165 in the BEAM/ATG and n = 29/148 in the CYC/ATG group, p = 0.385); antiviral treatment was administered in 26 cases (15 in the BEAM/ATG and 11 in the CYC/ATG group, p = 0.987) among the 64 patients with reactivation who reported details on CMV treatment. Median time to CMV reactivation was of 32 days (range 12–56) in the BEAM/ATG and 21 days (4–51 days) in the CYC/ATG group (Log-rank test: p = 0.520). Routine screening and monitoring for CMV was performed in 329 patients, not performed in 171 patients, not reported in the other cases. CMV reactivations were reported mostly in relation to high doses of ATG (rabbit ATG 7.5 mg/kg) and high CYC dose at mobilization (4 g/m2).

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reactivation was reported in 145/276 MS patients (52.5%; n = 43/132 in the BEAM/ATG and n = 102/144 in the CYC/ATG group, p < 0.001); EBV treatment was reported for 99/145 patients with EBV reactivation and a specific treatment was administered in 25 cases (5/25 in the BEAM/ATG and 20/25 in the CYC/ATG group, p = 0.006). No post-tranplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) was reported. Median time to EBV reactivation was 26 days (range 5–91) in the BEAM/ATG and 22 days (1–82 days) in the CYC/ATG group (Log-rank test: p < 0.001). Routine screening and monitoring for EBV was performed in 299 patients, not performed in 201 patients, not reported in the other cases. EBV reactivations were reported mostly in relation to high doses of ATG (rabbit ATG 7.5 mg/kg).

Fever of unknown origin (FUO) was reported in 116/348 MS patients (33.3%; n = 76/177 in the BEAM/ATG and n = 40/172 in the CYC/ATG group, p < 0.001); data on treatment was available for 97 patients with fever of unknown origin and a specific treatment was administered to all these cases (57/97 in the BEAM/ATG and 40/97 in the CYC/ATG group). Median time to FUO occurrence was 5 days (range 1–18) in the BEAM/ATG and 5 days (1–14 days) in the CYC/ATG group (Log-rank test: p < 0.001).

Sepsis was reported in 48/338 MS patients (14.2%; n = 44/161 in the BEAM/ATG and n = 4/177 in the CYC/ATG group, p < 0.001); a specific treatment was administered in 47 cases while for 1 patient the information was missing (43/47 in the BEAM/ATG and 4/47 in the CYC/ATG group). Median time to sepsis occurrence was 5 days (range 2–20) in the BEAM/ATG and 4 days (1–15 days) in the CYC/ATG group (Log-rank test: p < 0.001).

At day 100, infections with an identified pathogen occurred in 57/154 cases (37%; n = 37/110 in the BEAM/ATG and n = 20/44 in the CYC/ATG group, p = 0.166): first observed infection 21 bacterial, 9 viral, 2 fungal and 23 other infections (ie colitis, pneumonia, tonsillitis, catheter infection). Most patients (50/55) experienced only 1 episode of infection. Median time to first infection occurrence was 9 days (range 1–78) in the BEAM/ATG and 8 days (1–62 days) in the CYC/ATG group (log-rank: p = 0.122).

In the first 100 days, non-infectious complications occurred in 60/342 patients (39/174 in BEAM/ATG and 21/168 in CYC/ATG, p = 0.022) and were: mucositis (33; n = 29 in the BEAM/ATG and n = 4 in the CYC/ATG group, p < 0.001), liver toxicity (16; n = 7 in the BEAM/ATG and n = 9 in the CYC/ATG group, p = 0.037), renal/urinary tract complications (3, all in the CYC/ATG group), seizures (2, all in the CYC/ATG group), skin toxicity (2, all in the BEAM/ATG group), cardiac toxicity (1, in the CYC/ATG group), engraftment syndrome (2, all in the BEAM/ATG group), depression (1, in the BEAM/ATG group). Vaccinations were administered in 121/363 cases (33.3%), equally distributed in both groups of treatment (p = 0.234).

Different types and doses of ATG have been adopted. Most patients (88%) received rabbit ATG, with a prevalence of higher ATG doses in the BEAM/ATG group (p < 0.001; 7.5 mg/kg versus 6.5 mg/kg). Horse ATG was administered in 10% of patients, while goat ATG and monoclonal antibodies only in 2% of cases. ATG reaction was reported in 27/354 MS patients (7.6%; n = 25 in the BEAM/ATG and n = 2 in the CYC/ATG group); a specific treatment was administered in 14 cases (12 in the BEAM/ATG and 2 in the CYC/ATG group).

Data on pregnancy were reported only for 261 patients after HSCT (BEAM/ATG n = 154; CYC/ATG n = 107). A total of 13/261 pregnancies after transplant were observed, 11 cases in BEAM/ATG (11/154, 7%) and 2 cases in CYC/ATG (2/107, 2%), without significant differences in terms of potential impact from the type of conditioning regimen (p = 0.130) and similarly distributed between age ranges (18-30 vs 31-40 years). Median (IQR) age at transplant was 30 (26; 34) years. Data on the recurrence of spontaneous menstrual cycles after treatment was reported only for 144 females with <50 years. In the BEAM/ATG group, spontaneous menstrual cycles occurred in 29/78 patients (n = 18 in patients with 18–30 years, n = 9 in 31–40 years and n = 2 in 41–50 years at HSCT); in the CYC/ATG group, spontaneous menstrual cycles occurred in 5/66 patients (n = 4 in patients with 18–30 years and n = 1 in 31–40 years at HSCT; p < 0.001).

Discussion and conclusions

The intensity of the immunoablation in MS patients undergoing autologous HSCT is affected by different factors such as conditioning regimen, mobilization chemotherapy, graft manipulation (ie, CD34 selection), inclusion/dosage of serotherapy (ie. ATG) in the conditioning regimen [23], and prior DMTs. For these reasons, in this setting, it is commonly considered the ‘treatment’ intensity more than the simple conditioning intensity [24].

Intensive conditioning protocols, including total body irradiation or Busulfan, are associated with a higher risk of toxicity [25] and are generally no longer recommended. In this context, intermediate-intensity conditioning protocols, such as BEAM/ATG or CYC/ATG, have been widely adopted for HSCT in MS and are currently recommended by the European guidelines [9, 11]. In the last decade, CYC/ATG has become the most commonly used, owing to easier inpatient management and the influence of the MIST trial [5, 26]. A recent Swedish retrospective study compared 33 patients treated with BEAM/ATG and 141 with CYC/ATG, reporting similar efficacy but more severe adverse events and prolonged hospitalization in the BEAM/ATG cohort [18].

In this EBMT study with larger numbers, the two conditioning regimens performed similarly in terms of toxicity and efficacy. Similar neutrophil engraftment rates and times have been observed in the two groups. No significant differences among the two strategies have been observed in terms of mortality. Although a population with more severe and slightly more advanced forms of MS was reported for the BEAM/ATG cohort, the Kaplan-Meier estimate of NEDA failure in BEAM/ATG and CYC/ATG at 5 years was 42.3% and 44.1%, respectively, without statistically significant differences between the two treatments when adjusting for disease type, EDSS at baseline and year of transplant. However, long-term data may be partially affected by the fact that the median follow up is shorter in the CYC/ATG group as compared to the BEAM/ATG group.

In line with previous data [14], the disease type maintains a strong impact on outcomes. In this analysis, the proportion of NEDA patients at 5-year is 68% in the relapsing/remitting MS group versus 45% in the progressive MS group.

At day 100, a sub-analysis on early complications has mainly shown 21.6% CMV reactivations (similar rates in the two groups), 51.2% EBV reactivations (higher numbers in the CYC/ATG group), 33.1% FUO and 14.2% sepsis (higher numbers in the BEAM/ATG group), 32.9% infections (similar rates in the two groups), and 9.5% mucositis (higher numbers in the BEAM/ATG group). CMV and EBV reactivations are reported mostly in relation to high doses of ATG (ie rabbit ATG 7.5 mg/kg), while higher CYC dose at mobilization (CYC 4 g/m2) impacts only on the rates of CMV reactivations. CD34 selection was adopted only in a minority of patients, not allowing to properly investigate its role in this study.

However, given the registry-based nature of this study and the long period of data collection, more details on practices for screening, prophylaxis and monitoring of infectious complications are missing and data from earlier cohorts may be underreported. A recent EBMT ADWP survey has confirmed heterogeneity across centers in the current practices for diagnosis, monitoring, prophylaxis and therapy for CMV and EBV [27]. Although infections are common in MS patients undergoing HSCT, infectious adverse events are reported also using DMT, especially alemtuzumab and interferons [28].

MS is frequent in young women of childbearing age. Successful pregnancies after HSCT have been reported in the retrospective EBMT survey in ADs, without any apparent effects of conditioning regimens or increased risk of disease reactivation [11, 29]. In this study, a total of 13 pregnancies out of 261 females have been reported, without a significant impact of the conditioning regimen adopted. However, data on pregnancies are limited by the low numbers of patients reported for this specific item and the retrospective nature of the study.

This study has the strength of a large number of treated patients, but also limitations that include lack of randomization, retrospective assessment, heterogeneous and voluntary-based data reporting, and some differences in patient baseline characteristics and treatment epochs.

Despite the relevant number of patients included in this analysis and differently from the Swedish retrospective study [18], a clear difference between the regimens is lacking, both in terms of toxicity and efficacy. Type of disease (relapsing/remitting vs progressive) is still the major determinant of neurological outcome [14]. A prospective comparative trial is necessary to assess the risk/benefit ratio of the two regimens. However, in the meantime a tailored approach according to patients and disease characteristics might be considered.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

References

Fassas A, Anagnostopoulos A, Kazis A, Kapinas K, Sakellari I, Kimiskidis V, et al. Peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in the treatment of progressive multiple sclerosis: first results of a pilot study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;20:631–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1700944.

Burt RK, Traynor AE, Cohen B, Karlin KH, Davis FA, Stefoski D, et al. T cell-depleted autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis: report on the first three patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21:537–41. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1701129.

Alexander T, Greco R. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and cellular therapies for autoimmune diseases: overview and future considerations from the Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP) of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2022;57:1055–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-022-01702-w.

Boffa G, Massacesi L, Inglese M, Mariottini A, Capobianco M, Lucia M, et al. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000011461.

Burt RK, Balabanov R, Burman J, Sharrack B, Snowden JA, Oliveira MC, et al. Effect of Nonmyeloablative Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation vs Continued Disease-Modifying Therapy on Disease Progression in Patients With Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321:165–74. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.18743.

Das J, Snowden JA, Burman J, Freedman MS, Atkins H, Bowman M, et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation as a first-line disease-modifying therapy in patients with ‘aggressive’ multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2021;27:1198–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458520985238.

Mancardi GL, Sormani MP, Gualandi F, Saiz A, Carreras E, Merelli E, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis: a phase II trial. Neurology. 2015;84:981–8. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001329.

Snowden JA, Saccardi R, Allez M, Ardizzone S, Arnold R, Cervera R, et al. Haematopoietic SCT in severe autoimmune diseases: updated guidelines of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:770–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2011.185.

Sharrack B, Saccardi R, Alexander T, Badoglio M, Burman J, Farge D, et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and other cellular therapy in multiple sclerosis and immune-mediated neurological diseases: updated guidelines and recommendations from the EBMT Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP) and the Joint Accreditation Committee of EBMT and ISCT (JACIE). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55:283–306. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-019-0684-0.

Snowden JA, Sanchez-Ortega I, Corbacioglu S, Basak GW, Chabannon C, de la Camara R, et al. Indications for haematopoietic cell transplantation for haematological diseases, solid tumours and immune disorders: current practice in Europe, 2022. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2022;57:1217–39. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-022-01691-w.

Muraro PA, Mariottini A, Greco R, Burman J, Iacobaeus E, Inglese M, et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for treatment of multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder - recommendations from ECTRIMS and the EBMT. Nat Rev Neurol. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-024-01050-x.

Saccardi R, Freedman MS, Sormani MP, Atkins H, Farge D, Griffith LM, et al. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for aggressive multiple sclerosis: a position paper. Mult Scler. 2012;18:825–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458512438454.

Snowden JA, Badoglio M, Labopin M, Giebel S, McGrath E, Marjanovic Z, et al. Evolution, trends, outcomes, and economics of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in severe autoimmune diseases. Blood Adv. 2017;1:2742–55. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2017010041.

Muraro PA, Pasquini M, Atkins HL, Bowen JD, Farge D, Fassas A, et al. Long-term outcomes after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:459–69. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.5867.

Greco R, Badoglio M, Labopin M, Kaur M, Pasquini MC. The EBMT-ADWP and the CIBMTR. Handb Clin Neurol. 2024;202:295–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-90242-7.00008-0.

Burt RK, Marmont A, Oyama Y, Slavin S, Arnold R, Hiepe F, et al. Randomized controlled trials of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for autoimmune diseases: the evolution from myeloablative to lymphoablative transplant regimens. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3750–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22256.

Burt RK, Loh Y, Cohen B, Stefoski D, Balabanov R, Katsamakis G, et al. Autologous non-myeloablative haemopoietic stem cell transplantation in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase I/II study. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:244–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70017-1.

Silfverberg T, Zjukovskaja C, Noui Y, Carlson K, Auto MSSI, Burman J. BEAM or cyclophosphamide in autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2024;59:1601–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-024-02397-x.

Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, Carroll WM, Coetzee T, Comi G, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:162–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2.

Sormani MP, Muraro PA, Saccardi R, Mancardi G. NEDA status in highly active MS can be more easily obtained with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation than other drugs. Mult Scler. 2017;23:201–4. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458516645670.

Banwell B, Giovannoni G, Hawkes C, Lublin F. Editors’ welcome and a working definition for a multiple sclerosis cure. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2013;2:65–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2012.12.001.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33:1444–52. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444.

Ismail A, Nitti R, Sharrack B, Badoglio M, Ambron P, Labopin M, et al. ATG and other serotherapy in conditioning regimens for autologous HSCT in autoimmune diseases: a survey on behalf of the EBMT Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2024;59:1614–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-024-02383-3.

Burt RK, Farge D, Ruiz MA, Saccardi R, Snowden JA Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapies for Autoimmune Diseases. 2021; eBook: 978-1-315-15136-6: https://www.routledge.com/Hematopoietic-Stem-Cell-Transplantation-and-Cellular-Therapies-for-Autoimmune/Burt-Farge-Ruiz-Saccardi-Snowden/p/book/978113855855.

Atkins HL, Bowman M, Allan D, Anstee G, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, et al. Immunoablation and autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for aggressive multiple sclerosis: a multicentre single-group phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2016;388:576–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30169-6.

Burt RK, Han X, Quigley K, Helenowski IB, Balabanov R. Real-world application of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in 507 patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2022;269:2513–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10820-2.

Alexander T, Badoglio M, Labopin M, Daikeler T, Farge D, Kazmi M, et al. Monitoring and management of CMV and EBV after autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for autoimmune diseases: a survey of the EBMT Autoimmune Diseases Working party (ADWP). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2025;60:110–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-024-02461-6.

Tramacere I, Virgili G, Perduca V, Lucenteforte E, Benedetti MD, Capobussi M, et al. Adverse effects of immunotherapies for multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;11:CD012186.

Snarski E, Snowden JA, Oliveira MC, Simoes B, Badoglio M, Carlson K, et al. Onset and outcome of pregnancy after autologous haematopoietic SCT (AHSCT) for autoimmune diseases: a retrospective study of the EBMT autoimmune diseases working party (ADWP). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:216–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2014.248.

Acknowledgements

This work is dedicated to the memory, life, and work of Riccardo Saccardi MD. Riccardo fought valiantly against a prolonged illness and left us on February 19th 2024. The entire EBMT Autoimmune Diseases Working Party community will never forget the time Riccardo spent with us, his friendship, his personal and high scientific contribution. He was ADWP Chair for years 2004–2010, giving huge contribution to many EBMT and ADWP activities and dedication to advancing this field. His commitment to advancing the application of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in autoimmune diseases will continue to influence our work for many years to come. The authors contribute this article on behalf of Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP) of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). We acknowledge the ADWP for support in working party activities and outputs, and all EBMT member centers and their clinicians, data managers, and patients for their essential contributions to the EBMT registry. We would like to thank all participating centers (Supplementary Appendix material).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authorship group includes active representatives of the ADWP. RS, RG and JASnowden led on concept, design, coordination and data analysis, provided expert and analytical feedback. RS died during the preparation of this analysis. RG and JASnowden led on reviewing, writing and editing the manuscript. MP, AS and MPS performed the analysis of data, writing sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the acquisition and interpretation of information. All co-authors were involved in drafting the paper, revising it critically, and approval of the submitted and final versions. The EBMT provided resources via the working parties, data office and registry. Other than EBMT support there is no funding body supporting these guidelines, commercial or otherwise.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

AM discloses speaker honoraria for educational events from Biogen, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Sandoz, Sanofi, Viatris. ER declares speaker honoraria from Janssen. JAS discloses honoraria for advisory boards from Vertex, Jazz, BMS and Medac. PAM declares consulting for Teva, Glenmark and Cellerys. RG declares speaker honoraria for educational events from Biotest, Pfizer, Medac, Qiagen, Kyverna MSD and Magenta and advisory board from Pfizer, BMS. TA declares study support from Janssen Cilag. The remaining authors have nothing to declare.

Ethics

This study and registry data analysis were approved, led and supported by the Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP) of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Patients provided informed written consent for the inclusion of their non-identifiable data into the EBMT Registry. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Greco, R., Saccardi, R., Ponzano, M. et al. BEAM/ATG or cyclophosphamide/ATG as conditioning regimen in autologous haemopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis: a retrospective analysis of the EBMT autoimmune diseases working party. Bone Marrow Transplant 60, 1628–1634 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-025-02715-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-025-02715-x