Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease associated with age, prominently marked by articular cartilage degradation. In OA cartilage, the pathological manifestations show elevated chondrocyte hypertrophy and apoptosis. The mitochondrion serves as key energy supporter in eukaryotic cells and is tightly linked to a myriad of diseases including OA. As age advances, mitochondrial function declines progressively, which leads to an imbalance in chondrocyte energy homeostasis, partially initiating the process of cartilage degeneration. Elevated oxidative stress, impaired mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics jointly contribute to chondrocyte pathology, with mitochondrial DNA haplogroups, particularly haplogroup J, influencing OA progression. Therapeutic approaches directed at mitochondria have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in treating various diseases, with triphenylphosphonium (TPP) emerging as the most widely utilized molecule. Other strategies encompass Dequalinium (DQA), the Szeto-Schiller (SS) tetrapeptide family, the KLA peptide, and mitochondrial-penetrating peptides (MPP), etc. These molecules share common properties of lipophilicity and positive charge. Through various technological modifications, they are conjugated to nanocarriers, enabling targeted drug delivery to mitochondria. Therapeutic interventions targeting mitochondria offer a hopeful direction for OA treatment. In the future, mitochondria-targeted therapy is anticipated to improve the well-being of life for the majority of OA patients. This review summarizes the link between chondrocyte mitochondrial dysfunction and OA, as well as discusses promising mitochondria-targeted therapies and potential therapeutic compounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a prevalent joint disease, marked by joint cartilage degeneration alongside secondary hyperostosis, and usually accompanied by pain and physical disability, consequently leading to work incapacitation and diminished quality of life.1 In addition to the pain associated with joint damage, patients with OA also presented allodynia and hyperalgesia around the joint due to nerve sensitization, which further reduces the quality of life.2 Prevalence studies consistently indicate a close association between OA and age, particularly evident post the age of 50.3 Other risk factors encompass obesity, metabolic diseases, joint malformation, mechanical load and trauma.4 With the increase of aged population in developed countries, the incidence of OA will significantly increase and become a burden for society. As the elderly population burgeons in developed countries, the incidence of OA is predictable to escalate significantly, constituting a substantial societal burden. According to an epidemiological investigation, prevalent cases of OA increased from 247.51 million to 527.81 million globally from 1990 to 2019, which has shown an amplification of 13.25%.5

Despite the fact that the pathological characteristics of OA involve impairment of the entire joint structure, including remodeling of subchondral bone, osteophyte formation, and synovial inflammation,6 the primary pathological hallmark remains cartilage damage. Articular cartilage is primarily composed of chondrocytes and extracellular matrix (ECM), which is comprised of water (up to 80% of the wet weight), type II collagen, hyaluronans, and other proteoglycans synthesized by chondrocytes.7 Due to the avascular property of cartilage, the chondrocytes rely on passive diffusion from the synovial fluid (SF) to obtain essential oxygen and nutrients. Under physiological conditions, articular chondrocytes highly depend on glycolysis for energy production.8 Nevertheless, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation still contributes about 25% of the ATP.9 Chondrocytes show metabolic flexibility, which supports cell survival under nutrient stress by enhancing mitochondrial respiration. However, in OA chondrocytes, this flexibility is weakened, manifested by declined mitochondrial respiration and enhanced anaerobic glycolysis.10

The microscopic pathological manifestations of OA cartilage show chondrocyte hypertrophy and apoptosis, as well as ECM loss and calcification11,12(Fig. 1). While chondrocytes normally maintain cartilage integrity ECM synthesis, this anabolic function is impaired in OA cartilage, and may even lead to cartilage degradation with direct involvement of chondrocytes.13 Apoptosis of chondrocytes leads to pericellular matrix degradation and the release of apoptotic bodies into chondrocyte lacunae and in the interterritorial space, promoting pathological calcification in OA cartilage.14 In physiological endochondral ossification, chondrocyte hypertrophy occurs as an intermediate stage between chondrocyte maturation and apoptosis. In OA joints, hypertrophic chondrocytes are present near the mineralized cartilage matrix and the surface lesions, with diminished synthesis of collagen II and aberrant expression of alkaline phosphatase (ALP). However, although the current mainstream view of chondrocyte hypertrophy as one of the characteristics of OA, this claim is still open to debate.15

Articular cartilage structure and OA pathology. a Organization of articular cartilage. Articular cartilage mainly consists of chondrocytes and extracellular matrix (ECM). Oxygen and nutrients are delivered through the passive diffusion from the synovial fluid, thus forms a concentration gradient. b The microscopic pathological manifestations of OA cartilage show chondrocyte hypertrophy and apoptosis, as well as ECM loss and calcification

In eukaryotic cells, the bilayer organelle mitochondrion supplies energy through peroxidation phosphorylation and has an independently inherited genome.16 The outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), similar in composition to the plasma membrane, contains channels like voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) for small molecule transport, whereas the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) is protein-rich and contains negatively charged cardiolipin.17 Proteins comprising the respiratory chain reside on the IMM, bringing the tricarboxylic acid cycle in the matrix to convert ADP to ATP.18 Numerous studies have illustrated that mitochondrial dysfunction could lead to manifold diseases such as oncogenesis, neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic diseases, and musculoskeletal degenerative diseases, including OA.19,20

Currently, the organelle targeting treatment has gathered increasing interest among researchers. For most mitochondria targeting strategies, the molecules typically exhibit both lipophilicity and positive charge. The lipophilic nature facilitates insertion into the mitochondrial membrane via lipophilic affinity, while the positive charge interacts with the negative membrane potential and aids in translocating the molecule into the mitochondrial matrix.21 Since the mitochondrion is associated with multifarious diseases and its a pivotal role in cellular physiological processes, it is foreseeable that mitochondria-targeted drug delivery will emerge as a hotspot in biomedical research.

This review summarizes the link between chondrocyte mitochondrial dysfunction and OA, along with promising mitochondria targeting schemes and therapeutic compounds with potential implications for mitochondrial dysfunction. Our aim is to offer valuable perspectives into the advancement of mitochondria-targeted therapies for the treatment of OA.

Mitochondria in OA

As previously noted, the hypoxic environment within the articular cavity traditionally suggests that chondrocytes primarily derive energy from glycolysis. The significance of mitochondria in chondrocyte degeneration has gained increasing recognition in the last 20 years. Present studies have emphasized the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in OA pathogenesis. Alterations in mitochondrial function induced by oxidative stress or mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) heterogeneity have been implicated in chondrocyte apoptosis.22

Mitochondrial oxidative stress and antioxidant system

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) refer to a broad category of oxygen-containing free radicals and peroxides that readily generate oxygen radicals within organisms, which includes hydroxyl radical (•OH), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anion (O2•−), and nitric oxide (NO), etc. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is one of the primary contributors of intracellular ROS.23 Oxidative stress refers to the imbalance between the generation of ROS and antioxidant defense, resulting in an elevated level of oxidation intermediates, ultimately culminating in mitochondrial dysfunction.

A heightened state of oxidative stress has been noted in patients with OA. A study has demonstrated that synovial cells in OA patients exhibit significant lipid peroxidation measured by the lipid peroxidation product malondialdehyde (MDA), possibly mediated by NO or other ROS produced by chondrocytes.24 Ostalowska et al. have found significantly increased antioxidant enzyme activity in knee osteoarthritis (KOA) patients, with the MDA level showing a rising trend (though not statistically significant). These findings suggest that elevated antioxidant enzyme levels may represent an adaptive response to increased ROS in SF, although the enzyme levels tend to decline as the disease progresses. They also found that the secondary OA exhibits heightened compensatory antioxidant responses and more pronounced oxidative tissue damage (lower SF viscosity), likely driven by trauma-induced inflammation, whereas primary OA reflects chronic adaptive mechanisms despite longer disease duration.25

Excessive level of ROS can induce mitochondrial damage by triggering mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT), membrane depolarization, IMM cardiolipin peroxidation, and cytochrome c release from both MPT dependent and independent pathway,26 which then enters the cytoplasm and activates the caspase cascade to trigger chondrocyte apoptosis,27 along with impaired mtDNA integrity and repair capabilities28(Fig. 2). This consequently instigates a cycle of sustained ROS production and release, fosters regional persistent oxidative stress and chronic inflammation,29 and eventually result in chondrocyte death.30 Moderate mechanical stress has been demonstrated to preserve mitochondrial function and effectively clearing ROS, thus mitigating IL-1β-induced chondrocyte apoptosis. Conversely, intense mechanical stress can induce severe mitochondrial dysfunction.31 Additionally, aging enhances mitochondrial-associated ROS production in chondrocytes, thereby exacerbating OA progression.32

Excessive level of ROS promotes cytochrome c release via two distinct mechanisms: (1) MPT-dependent pathways, where ROS oxidize thiol groups on the adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT), inducing MPT, matrix swelling, and OMM rupture; and (2) MPT-independent pathways, involving cardiolipin peroxidation—which destabilizes cytochrome c binding to IMM—and subsequent release through OMM channels (e.g., VDAC) or Bax/Bak oligomerization. Cytochrome c then enters the cytoplasm and activates the caspase cascade to trigger chondrocyte apoptosis

Organisms possess antioxidants that counteract the effects of ROS, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione (GSH), etc. Among these enzymes, SOD catalyzes the dismutation of O2•− into H2O2 and O2, subsequently other antioxidants such as CAT converting H2O2 into H2O.33 The major O2•− scavenger, the SOD family consists of three members: SOD1, SOD2 and SOD3. Among them, SOD2 is primarily localized in the mitochondria, while SOD1 predominantly resides in the cytoplasm, and SOD3 mainly exists in the ECM.

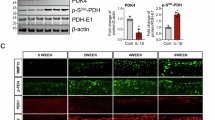

Studies have demonstrated that the SOD family is abundantly expressed in chondrocytes. However, in OA chondrocytes, there is a notable decrease in SOD expression, especially SOD2.34,35 Controversially, another research mentioned that serum SOD2 levels increased in patients with OA, indicating an elevated oxidative stress related with OA.36 Under oxidative stress, the expressions of both SOD1 and SOD2 are upregulated.37 Mechanical overload also reduced the expression and protein level of SOD2 gene in knee joint chondrocytes, which leads to excess production of mitochondrial superoxide, ultimately resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent cartilage damage.38 The activity of SOD2 in chondrocytes declines with age,32 possibly due to reversible acetylation modification. However, this effect can be relieved by the deacetylation ability of SIRT339 (Fig. 3).

The structure of the mitochondrion. IMM and OMM are phospholipid bilayers surrounding mitochondrial matrix. The components of mitochondrial electron transport chain are located on IMM, including complexes I-IV and ATP synthase, among which the complexes I and III are the major source of O2•−. SOD2 catalyses the dismutation of O2•− into H2O2 and O2, subsequently other antioxidants such as CAT converting H2O2 into H2O. The activity of SOD2 can be upregulated by the deacetylation of SIRT3. ΔΨ, mitochondrial membrane potential; mPTP, mitochondrial permeability transition pore; MPT, mitochondrial permeability transition; OMM, outer mitochondrial membrane; IMM, inner mitochondrial membrane

SIRT3, a member of the sirtuin family, serves as a major deacetylase located in mitochondria that deacetylates various mitochondrial antioxidant enzymes, including isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH2)40 and SOD2.41 Under oxidative stress, the SIRT3 expression is downregulated.37 Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4 isoform 2 (COX4I2) is also a substrate of SIRT3, the deacetylation of which rescues maintain mitochondrial homeostasis and attenuates the progression of post-traumatic OA.42 Loss of SIRT3 impairs the function of antioxidant proteins by impeding mitochondrial aerobic respiration, leading to amassment of ROS and RNS and accelerating.42 The antioxidant ability of SIRT3 also depended on IDH2, which has been found to be able to defend cells against oxidative stress through elevated GSH levels.43

Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2(Nrf2) is a transcription factor serves as a communication bridge between the nucleus and the mitochondria, responding to ROS-induced oxidative stress.44 The Nrf2 pathway is activated in response to oxidative stress, which is essential for mitigating mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) levels and preserving mitochondrial structural integrity.45 It has been proved that the kinases Mst1 and Mst2 detect ROS and preserve cellular redox by regulating the stability of Nrf2 in macrophages.46 In rat model of OA, the nuclear localization of Nrf2 enhanced by Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid (TRPV)-1 activation via the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)/Nrf2 signaling pathway inhibited M1 macrophage polarization in synovium, thus attenuating OA progression.47

Heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) is an iron-dependent antioxidant enzyme, with its expression and activity upregulated by Nrf2.48 In OA chondrocytes, the expression of HO-1 is elevated,49 but downregulated upon stimulation of pro-inflammatory factors such as TNF- α, IL-1β and IL-17.50 HO-1 plays a protective role by reducing ROS production, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) as well as pro-inflammatory factors in OA chondrocytes.51 In mouse models with HO-1 overexpressed, the level of SOD2 is upregulated and the chondrocytes apoptosis is suppressed.52 The activation of Nrf2/HO-1 axis suppresses OA development through downregulating NF-κB.53

Under oxidative stress conditions, Nrf2 has been demonstrated to upregulate the expression of PTEN-induced putative kinase 1(PINK1)54 and Parkin,55 ultimately inducing mitophagy.56 The activation of Nrf2/Parkin axis alleviates OA progress.55 Additionally, increased Nrf2 activity contributes to the degradation of Dynamin-Related Protein 1(Drp1), consequently inhibiting the fission of mitochondria.57 However, another study has demonstrated that Nrf2 over-expression activated ERK1/2,50 which in turn activates DRP1 in a pathologic condition.58 Nrf2 also modulates mitochondrial biogenesis via the activation of HO-1,59 potentially mediated by the production of carbon monoxide (CO).60 These findings indicate the association of oxidative stress with mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics.

NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3), serves as an intracellular sensor that detects a variety of pathogenic signals, triggering the assembly and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.61 Research has demonstrated that reduced level of ROS restrains the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in vitro.62 Inhibition of TRPV4, a calcium-permeable cation channel, suppresses the polarization of M1 macrophages in synovium via the ROS/NLRP3 pathway, thereby delaying OA progression.63 Conversely, silencing Nrf2/HO-1 pathway activates the NLRP3 inflammasome,64 while elevated Nrf2 expression reduces mitochondrial ROS production, thereby inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation,65 potentially contributing to the progression of OA.

Several other molecules have been reported to regulate the oxidative stress of mitochondria. Notably, sterol carrier protein 2 (SCP2) is highly expressed in human OA cartilage, where it is associated with the accumulation of lipid hydroperoxides (LPO). This accumulation leads to increased mitochondrial oxidative stress and subsequent ROS release. Inhibition of SCP2 can provide significant protection to mitochondria, reduce LPO levels, alleviate chondrocytes ferroptosis in vitro, consequently mitigate the progression of OA in rats.66 Kindlin-2 deficiency results in mice spontaneous OA and instability-induced OA lesions by exacerbating mitochondrial oxidative stress.67 The deletion of Krüppel-like factors 10/TGFβ inducible early gene-1 (Klf10/TIEG1) in mice can reduce ROS level in senescent mouse chondrocytes and restore mitochondrial membrane potential.68

Mitophagy

Mitophagy is a process that selectively eliminates damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria through autophagy mechanism. Under normal physiological conditions, this process ensures mitochondrial homeostasis. It can be triggered by a variety of factors, including mechanical stress,31 hypoxia, oxidative stress69, and iron starvation.70 Mitophagy impairment leads to cell apoptosis and ECM degradation.71 Mitochondrial autophagy pathway is divided into Parkin-dependent pathway and Parkin-independent pathway.71

It has been proven that the Parkin-dependent pathway is triggered by significant mitochondrial depolarization induced by mitochondrial uncouplers72 or acute production of mtROS.73 Meanwhile, Parkin-independent pathway can be induced by hypoxia.74 However, few studies have clarified how chondrocytes choose between these two pathways.

Parkin-dependent pathway is induced by PINK1 and E3-ubiquitin ligase Parkin.75 There is a mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS) attached to the N-terminus of PINK1, allowing PINK1 to be introduced into the IMM through translocases located in both of the OMM and the IMM in a mitochondrial transmembrane potential-dependent way. Then mitochondrial matrix processing peptidase and presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protein (PARL) cleave PINK1, maintaining a relatively low level of PINK1.76,77

When mitochondria sustain damage, abnormal mitochondrial transmembrane potential blocks the translocation of PINK1, therefore, PINK1 is bound to the translocase of the OMM. Parkin is attracted to the mitochondria from the cytoplasm and triggers ubiquitination of mitochondrial membrane proteins including VDAC1,78 mitofusin 1 (MFN1) and mitofusin 2(MFN2),79 subsequently facilitating the recruitment of p62/SQSTM1/sequestosome-178 and microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3).80 These effects impede the re-fusion of impaired and normal mitochondria, separating damaged mitochondria for subsequent incorporation into autophagosomes,80 which then fuse with lysosomes to degrade damaged mitochondria.81

Mild and sustained H2O2 stimulation can lead to Parkin-dependent mitophagy in vitro.82 In response to IL-1β stimulation, chondrocytes lacking Parkin expression exhibit compromised mitophagy, eventually resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction and elevated oxidative stress.83 Overexpression of Parkin can diminish mitochondrial ROS levels and chondrocyte apoptosis by clearing dysfunctional mitochondria.84 By comparison, a study conducted on a monosodium iodoacetate (MIA) -induced rat OA model revealed that deletion of Pink1 could mitigate cartilage damage.85

Activation of AMPK/SIRT3 pathway induces Parkin expression, parkin-dependent mitochondrial autophagy, and SOD2 activation, which coordinately alleviate mitochondrial stress.86,87 Through suppressing SIRT3 expression and consequently inhibiting Parkin-dependent mitophagy, IL-1β triggers chondrocytes apoptosis.88 α-ketoglutaric acid (α-KG) is a key metabolic intermediate in the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle.89 It has been shown that α-KG level is lower in IL-1β-induced OA chondrocytes and human OA cartilage compared with normal cartilage. α-KG enhances the transcription of PINK1, Parki,n and other proteins, promoting mitochondrial autophagy and inhibits ROS production, thereby alleviating OA symptoms.90

Parkin-independent mitophagy pathway mainly relies on OMM proteins, which includes NIP3-like protein X/BNIP3-like protein(NIX/BNIP3L), BCL2 interacting protein 3 (BNIP3)91 and FUN14 domain protein 1 (FUNDC1).74 Skipping of ubiquitination, these proteins that can directly initiate mitophagy of the impaired mitochondria via the interaction between their LC3-interacting region (LIR) domain and LC3.92 The transcription of BNIP3 and NIX is positively modulated by hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit α(HIF-1α).93 The expression of HIF-1α increases in OA cartilage, and promotes mitophagy to perform a protective effect on chondrocytes.94 Downregulation of Klf10 upregulates BNIP3, therefore promotes mitophagy.68 Knocking down proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) can activate mitophagy by promoting the expression of BNIP3.95 ATAD3Bs is a novel mitotic receptor which contains a LIR motif that binds to LC3 and exacerbates Parkin-independent mitophagy induced by oxidative stress.69 Additionally, Mechanical stress strength-dependently promotes chondrocytes mitophagy.31

Mitochondrial dynamics and biogenesis

Mitochondrial dynamics is defined as the dynamic equilibrium between the fusion and fission of mitochondria. This mechanism is essential to preserving mitochondrial quality and function.96 Dynamin-Related Protein 1(DRP1) is a GTPase, functioning as a key regulator of mitochondrial fission and can be upregulated by IL-1β.97 Suppression of DRP1-mediated mitochondrial fission blocks mitochondrial damage and chondrocyte apoptosis induced by IL-1β. ERK1/2 activates DRP1 in pathologic condition, the inhibition of which can suppress DRP1 activation, thereby mitigating mitochondrial network disruption and apoptosis in chondrocytes.58

TRPV4 is capable to activate DRP1 mitochondrial translocation via Ca2+ fluxion, leading to excessive mitochondrial fragmentation. In the anterior cruciate ligament transection (ACLT) mouse model, TRPV4 inhibition reversed cartilage degeneration mediated by DRP1.98 Chondrocyte-targeted delivery of Nrf2 inhibited the phosphorylation and mitochondrial translocation of DRP1, thereby averting mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction, consequently attenuating cartilaginous endplate degeneration in vivo.99 In OA mouse models, TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) overexpression results in DRP1 Ser637 phosphorylation, inhibiting mitochondrial fragmentation and promoting the fusion of impaired mitochondria with autophagosomal membranes during mitophagy.100 In the presence of norepinephrine (NE) stimulation, mitochondrial dynamics in chondrocytes is enhanced through the upregulation of MFN1/2, Optic Atrophy Protein 1(OPA1) and DRP1.101

OPA1, along with MFN1/2, mediates mitochondrial fusion. MFN1/2 primarily regulate OMM fusion, whereas OPA1 predominantly manages IMM fusion.102 OPA1 is a GTPase, which is subject to the deacetylation and activation by SIRT3, thus regulating mitochondrial dynamics to preserve the integrity of mitochondrial network.103 Moderate mechanical stress fosters mitochondrial dynamics, preserving mitochondrial quality by upregulating MFN1/2 and OPA1 and facilitating the DRP1 translocation from cytoplasm to mitochondria.31 Conditional deletion of OPA1 leads to cartilage degeneration, eventually resulting in OA in aged mice.104

The expression of MFN2 is increased in both human and rat OA chondrocytes,105 along with chondrocytes stimulated by IL-1β.106 In the destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) rat model, Overexpression of MFN2 in articular cartilage accelerated the progression of OA, while knockdown of MFN2 mitigated cartilage degeneration.107 In contrast, another study has reported that overexpression of MFN2 enhances chondrocyte-specific gene expression and exhibits protective effects against OA.108 Stimulation of IL-1β downregulates the expression of MFN1.97 However, the relationship between MFN1 and OA chondrocytes has not been fully studied.

Adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a pivotal regulator of energy homeostasis109 and is important for in mitochondrial biogenesis.110 The expression of AMPK is decreased in both mouse and human OA articular chondrocytes.111,112 Conversely, activation of AMPK signaling has been illustrated to protect chondrocytes from apoptosis.113,114 AMPK activator preserves mtDNA integrity and improves mitochondrial function in chondrocytes by reducing acetylation and upregulating SOD2 expression via the SIRT3 pathway, therefore attenuating aging-associated mouse KOA.115 Promoted AMPK signaling induces mitochondrial division, consequently increases the number of mitochondria in chondrocytes.116

AMPK regulates SIRT1, a NAD+-dependent deacetylase, with the important substrate PGC-1α.117 SIRT1, belonging to the same sirtuin family as SIRT3, predominantly localizes in the nucleus and the cytoplasm.118 The expression of SIRT1 is downregulated under various stresses known to induce apoptosis of human chondrocytes. The overexpression of SIRT1 counteracted the high glucose-induced upregulation of DRP1 and downregulation of MFN1, thereby diminishing mitochondrial fission.119 Inhibition of the AMPK /SIRT1/PGC-1α pathway reduces the expression of mitochondrial fusion proteins and suppresses mitochondrial function in chondrocytes, consequently exacerbating OA.120,121 In contrast, the activation of AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α pathway promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and fusion, thereby reducing oxidative stress in chondrocytes.121,122 The same effect in the spinal cord relieves OA pain.123

The key proteins and signaling pathways involved in mitochondrial dynamics are summarized in Fig. 4.

Summary of the key proteins and signaling pathways involved in mitochondrial dynamics. Mitochondrial fission is mainly mediated by DRP1, which binds to the OMM in a ring-like structure, and then the organelle divides into two separate mitochondria. OPA1, together with MFN1/2, mediates mitochondrial fusion, with MFN1/2 mainly regulating OMM fusion and OPA1 primarily controlling IMM fusion. Red arrows indicate activation or upregulation of pathway; while blue lines indicate repression or inhibition of the pathway. OMM, outer mitochondrial membrane; IMM, inner mitochondrial membrane; DRP1, Dynamin-Related Protein 1; MFN1 and MFN2, mitofusin 1 and mitofusin 2; OPA1, Optic Atrophy Protein 1

mtDNA haplogroup

Mitochondria possess their own DNA, which is inherited independently from nuclear genomes. mtDNA is maternal inherited and exhibits a remarkably high mutation rate, allowing for continuous evolution through the accumulation of genetic variations.22 mtDNA haplogroup refers to a specific set of mtDNA polymorphisms with continent specificity.124 These haplogroups are intricately relevant to the pathogenesis, progression, and prognosis of OA.

The protective effects of mtDNA haplogroups can be manifested at the molecular level. mtDNA haplogroup J carriers have shown reduced consumption of oxygen and diminished production of ATP and ROS than non J variants,125 whereas haplogroup H carriers demonstrate higher mitochondrial oxidative damage, oxygen consumption and ROS production.126 In correspondence, haplogroup J cybrids display the same property, along with increased cell survival under oxidative stress.127 In vitro, chondrocytes from haplogroup J carriers demonstrate decreased NO production.128 In addition to influencing ROS production, mtDNA haplogroups have been illustrated to impact serum levels of antioxidant enzymes. Carriers of mtDNA haplogroup J exhibit a higher level of serum catalase compared to non-J carriers, while a trend of lower serum level of SOD2 has been found in carriers of haplogroup H.36

Besides, serum biomarkers relevant with OA are also affected. MMP3, also known as Stromelysin 1, can cause ECM cleavage129 while MMP13, or collagenase 3, is essential for the degradation of type II collagen, the primary component of superficial layers of cartilage.130 Both enzymes are upregulated with the progression of OA13,131 and make contributions to OA development by affecting joint cartilage ECM integrity.132 In OA patients, the serum level of MMP3 increases,131,133 and this change was more significant in carriers of haplogroup H. Additionally, a trend has been observed for haplogroup J carriers to have lower serum levels of MMP-13 than carriers of the mtDNA haplogroup H.133 Correspondingly, it has been observed that serum type II collagen in mtDNA haplogroup H carriers was more abundant, whereas haplogroup J carriers display lower levels.134 However, in haplogroup J cybrids, the expression of SIRT3 is initially lower than in H cybrids under moderate H2O2 stimulation. However, as the stimulation becomes severe, this difference disappears.37

The distinct impact of mtDNA haplogroups on OA is also clinically validated. Several European researchers have reported a reduced risk of KOA and hip OA in mtDNA haplogroup J carriers.127,135,136 Additionally, haplogroup T is linked to a decreased risk of KOA.137 Nevertheless, this effect may vary with regions and races.138 The association between mtDNA haplogroups and OA has also been described in Asian studies. Fang et al. has indicated that haplogroup B may serve as a protective factor against OA, while haplogroup G appears to have the opposite effect.139 This may because of the elevated mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in haplogroup G cybrids than in haplogroup B cybrids.140 Conversely, Koo et al. have suggested that mtDNA haplogroup B contributes to the onset of KOA.141

In radiography studies, knees of radiographic KOA patients carrying haplogroup J significantly decrease the risk of medium to large bone marrow lesions in the medial compartment.142 In patients with KOA, mtDNA haplogroup T was associated with the lowest increase in Kellgren-Lawrence grade, indicating a reduced risk of radiological progression.143 The TJ cluster of mtDNA haplogroups has revealed a milder radiographic OA progression, primarily driven by type T.144 In comparison, haplogroup Uk has been associated with rapid progression of OA.145(Table 1).

Treatments targeting on mitochondria

Modified nanomaterials targeting on chondrocytes

In recent years, the polymer or lipid-based nanocarrier has emerged as a prominent drug delivery strategy. These nanoparticles are transported into cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis via caveolin-dependent, clathrin-dependent, or micropinocytosis pathways.146 Additionally, in order to ensure the rate of endocytosis, the optimal particle radius is preferably 25−30 nm.147

There have been reports regarding the use of modified nanocarriers for OA treatment. To target chondrocytes, the surface of these nanocarriers is typically modified with chondrocyte affinity peptides (CAP) or WYRGRL peptide. Another strategy takes advantage of the cationic charges of the nanocarriers to approach the chondrocyte ECM, which is composed of negative charged glycosaminoglycans,148 coinciding with the strategies of targeting mitochondria discussed later.

Primary chondrocytes-derived exosomes cultured under normal conditions have been demonstrated to ameliorate mitochondrial dysfunction and impede OA progression.149 Transplantation of mitochondria derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells has been shown to promote mitochondrial biogenesis.106 Kim et al. researchers have designed fusogenic capsules synthesized by a neutral lipid (1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine, DSPE) and a cationic lipid (1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane, DOTAP) to effectively encapsule and transfer mitochondria from mesenchymal stem cells to chondrocytes, leading to reduction in the expression of inflammatory cytokines and MMP13, while promoting cartilage regeneration. Besides, they observed that the encapsulation efficiency increased in proportion to the amount of DOTAP, indicating that cationic substance exhibit affinity with anionic mitochondria.150 Chen et al. have constructed the cartilage-targeted nanomicelles modified with the WYRGRL peptide, which were developed to deliver Pioglitazone. The nanomicelles reduced intracellular ROS levels and restored the mitochondrial membrane potential, eventually inhibited H2O2-induced chondrocyte death and delayed OA progression.151

Mitochondria-targeting strategies

Constructing nanoparticles through coating drugs with lipids and subsequently modifying their surface with mitochondria-targeting molecules has proven to be a viable approach. Examples of these molecules include triphenylphosphonium (TPP), Dequalinium (DQA), Szeto-Schiller (SS) tetra-peptide family, the KLA peptide, mitochondrial penetrating peptides (MPP), etc.152 (Table 2).

Cations for modification

For most mitochondria-targeting cations, the molecules share two common properties: lipophilicity and positive charge. The former enables insertion into the mitochondrial membrane via lipophilic affinity, while the latter capacitate translocation into the mitochondrial matrix depending on the negative membrane potential, which can reach up to -180 mV.21,153

Among cations, TPP has been most extensively applied for modification to target mitochondria. TPP is a lipophilic cation featuring a phosphorus atom surrounded by three hydrophobic phenyl groups.21 Its ability to aggregate in mitochondria has already been discovered since the 1960s, the mechanism of which has been thoroughly explored.154,155,156 According to the Nernst equation, at physiological temperatures, for every 60 mV increase in membrane potential, the accumulation of TPP within mitochondria will increase by a factor of 10. Given that the mitochondrial membrane potential typically ranges from 140 to 180 mV, the TPP cation is able to accumulate several hundred-fold within the mitochondrial matrix, presenting a highly efficient targeting ability.154 During the last 20 years, a series of mitochondria-targeted antioxidants have been developed through the covalent attachment of the TPP cation to various antioxidant molecules, including derivatives of ubiquinol (MitoQ) and alpha-tocopherol (MitoVit E), etc.154,157

Recently, increasingly numerous studies have combined TPP with nanocarriers to target mitochondria for drug delivery. In another research, modified exosomes coated with circRNA mSCAR (a mitochondrial circular RNA) with TPP- poly-D-lysine (PDL) were able to target macrophages mitochondria, thereby reducing the level of mtROS, facilitating the polarization of macrophages towards M2 phenotype and alleviating sepsis in mice.158 In another study, nanoparticles modified with TPP were synthesized to selectively target bone marrow-derived macrophages mitochondria. These nanoparticles inhibited production of mtROS, thus performs protective effect against OA.159

DQA is a lipophilic dication, consisting of two cationic quinolinium moieties connected by a 10-carbon alkyl chain.21 The chloride of DQA has antibacterial and anticancer activity.160,161 Bae et al. constructed nanoparticles composed of DQA/DOTAP/ 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), which enhanced ROS production and impaired mitochondrial membrane potential, eventually inducing cell apoptosis.162 In another study, for cancer therapy, researchers synthesized an amphiphilic polymeric nanoparticle using glycol chitosan, with DQA serving as both the mitochondria-targeting moiety and the lipophilic component.163 However, due to the cytotoxicity of DQA, which inhibits the production of mitochondrial ATP and thus inhibits cell growth,164 it may be difficult to apply DQA in the field of cell repairment.

In addition to these two cations, rhodamine derivatives are also able to selectively accumulate in mitochondria.165 The targeting mechanism is similar to the two cations mentioned above, but because rhodamine has one less positive charge than the two positive charges of DQA, its targeting ability and therapeutic efficacy are considered to be not as good.164 Rhodamine is often applied as dyes for fluorescent probes and biomolecular tracer.166,167 At higher concentration, it performs cytotoxity towards cancer cells.168 Rhodamine 19 derivatives can act as mild mitochondria-targeted cationic uncouplers, causing a limited decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential.169 Consequently, ATP production would decrease, but ROS production would also decline.170 However, researches on rhodamine derivatives modification for mitochondrial-targeted drug delivery are extremely rare.

Peptides for modification

The SS-peptides are small, water-soluble tetrapeptides characterized by a structural motif of alternating basic amino acids and aromatic residues. This structural feature allows the SS peptides to selectively accumulated on IMM depending on mitochondrial membrane potential.171 It has been found that SS03 could achieve a 100-fold concentration in mitochondria after incubated with mouse liver mitochondria.172 Nevertheless, their ability to pass into the mitochondrial matrix is relatively insufficient.172 The components of the SS peptides include tyrosine (Tyr), dimethyltyrosine (Dmt), arginine (Arg), phenylalanine (Phe), and lysine (Lys) residues, among which Tyr and Dmt perform antioxidant activity and scavenge ROS.21

The mechanism by which SS peptides pass through OMM is poorly reported, but given that the composition of OMM is similar to the plasma membrane, there may be some reference. Take SS02 as an example, prior to the discovery of its mitochondrial targeting ability, SS02 was considered an opioid analog. It has been demonstrated that there is an energy-independent way for the cellular uptake of SS02.173

Treatment with SS31 alone could reserve mitochondrial function through Sirt3/PGC-1α signaling pathway174 and upregulate OPA1 via Sirt3.175 Li et al. have constructed a nanozyme called Mn3O4@PDA@Pd-SS31, which targeted mitochondria via SS31 modification. This nanozyme simulated SOD activity, effectively clearing chondrocyte mtROS, thereby reserving mitochondrial dysfunction, promoting mitophagy, and alleviating OA progression.176 Hui Wang et al. used the combination of SS peptides and the antioxidant Tiron to achieve a significant diminishing of LPS-mediated mtROS production in mouse LPS model of acute lung injury.177

Inspired by SS peptides, Mitochondrial penetrating peptides (MPP) were primarily synthesized by Horton et al. MPP contain four or eight residues, forming a motif of alternating cationic and hydrophobic residues comparable similar to SS peptides, with Lys and Arg providing positive charge while Phe and cyclohexylalanine residues imparting lipophilicity.178 Yousif et al have reported that rather than endocytosis, MPP seems to cross the plasma membrane through direct uptake, and relys on a balanced, dispersed distribution of cationic charge and hydrophobicity to traverse mitochondrial membranes. In addition, successful cargo delivery requires a logP ≥ -2.5 of the drug (logP: The logarithm of a compound’s partition coefficient between octanol and water, indicating its lipophilicity and membrane permeability potential).179

A compound composing pyrrole-imidazole polyamides, MPP and chlorambucil has been discovered to be capable of selectively modulating mtDNA mutations.180 Yang et al. have designed a MPP-modified Doxorubicin-loaded N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymer conjugates to target mitochondria, aiming to address mitochondrial dysfunction and achieve anticancer effects.181

The KLA peptides with amino acid sequence KLAKLAKKLAKLAK also possess mitochondrial targeting ability. Primarily, they were employed as disruptors of the mitochondrial membrane to induce cell apoptosis,182 thus making them mainly applicable in tumor therapy due to their cytotoxic properties. Yang et al. constructed a polymeric dual-drug nanoparticle that integrates an oxaliplatin derivate with the mitochondria-targeting peptide FKLAK. This innovative nanoparticle could disrupt mitochondrial membrane potential and inhibit ATP-dependent processes, such as drug efflux and DNA damage repair in tumor cells, resulting in enhanced anticancer activity.183 Cheng et al. utilized the KLA peptide to modify nanoparticles equipped with a thioketal linker that could respond to elevated levels of ROS around mitochondria, subsequently transform into the fibrous structures, and demonstrated multivalent cooperative interactions with mitochondria.184

Other modification methods

Doxorubicin (DOX) has been extensively used as an anticancer drug in clinic. However, it performs cardiotoxic effects, with mitochondrial membrane as the major target of cellular toxicity.185 Xi et al. initiatively found that a straightforward amphiphilic modification, realized by connecting lipids to DOX through a PEG linker, could enable its selective accumulation in tumor cell mitochondria in vivo.186 This strategy has been used by Wang et al. to construct a mesoporous silicon-coated gold nanorods modified with DSPE-PEG2000-DOX, the nanoparticle played the role of the carrier of NO prodrug (BNN6) and achieved the mitochondrial site-specific release of NO.187

The physiological process of mitochondrial respiration can also be exploited as a target. Pyruvate, an organic compound that participates in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, can be specifically transported into mitochondria by the monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) on the OMM.188 Wang et al. used pyruvate to modify a silica-carbon hybrid nanoparticle coated with lipid membrane, thereby specifically producing ROS in mitochondria and targeting DOX to mitochondria.189

Nanomaterials naturally targeting on mitochondria

Despite modified compounds, there exist other organic molecules that naturally targeting mitochondria. Dihydromyricetin (DMY) is a natural agonist of SIRT3,190 which is a deacetylase localized in mitochondria as mentioned before. Xia et al. used microfluidic technology to achieve the formation of a molecule termed DMY@HGP, which consisted of gelatin methacrylate and benzenediboronic acid (PBA) anchored to hyaluronic acid methacrylate. Given PBA’s sensitivity to ROS, intra-articular injection of DMY@HGP ROS-responsively restored the endogenous balance between mitochondrial apoptosis and mitophagy, consequently ameliorating cartilage wear and subchondral osteosclerosis in mice with an OA model induced by trauma.191

Urolithin A(UA) is a natural compound known to activate mitophagy and promote mitochondrial respiration in primary chondrocytes from both healthy donors and OA patients. This activity contributed to the mitigation of cartilage degeneration in a mouse OA model.192 Chen et al. modified chondrophilic peptide (WYRGRL) on the surface of UA-carrying liposomes by microfluidic technology. These liposomes were then integrated into methacrylate hyaluronic acid hydrogel microspheres, which were capable of targeting chondrocytes and selectively remove subcellular dysfunction mitochondria.193

Other medicines affecting chondrocytes mitochondria

There are several medicals illustrated to affect mitochondria, either by diminishing oxidative stress or by activating signaling pathways on mitochondrial dynamics.

Pretreatment with Angelica sinensis polysaccharide (ASP) has been demonstrated to notably activate SOD2 in tert butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) -cultured rat chondrocytes, effectively clearing ROS and promoting mitochondrial metabolism.194 In addition, ASP exhibits protective effects in chondrocytes against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis mediated by mitochondrial signaling pathway.195 Prussian Blue nanoparticles (PBNPs) exhibit antioxidant activity. Zhou et al. discovered that PBNPs alleviated intracellular oxidative stress by stabilizing SOD1, thereby preserving mitochondrial structure, enhancing antioxidant capacity, and ultimately rescuing ROS-induced intervertebral disc degeneration in a rat model.196 Astaxanthin (ATX) is a natural ketocarotenoid pigment. Wang et al. have illustrated that ATX was able to restore GSH levels, clear ROS, reserve mitochondrial membrane potential, and structure damage in chondrocytes under the stimulation of IL-1β.197

Metformin has been demonstrated to upregulate both AMPK and LC3 expression in articular cartilage tissue,114,198 and act as an activator of Parkin-dependent mitophagy via the SIRT3 signaling pathway, combating IL-1β-induced oxidative stress in chondrocytes.87 Administration of metformin has significantly reduced cartilage degradation in DMM mouse model.114 Gastrodin (GAS), derived from Gastrodia elata, along with Irisin, a soluble peptide upregulated by the PGC-1α signaling pathway, and Mitochonic acid-5, a mitochondrial homing drug, all activate the SIRT3/Parkin pathway, thus enhancing mitochondrial membrane potential and promoting mitophagy.88,97,199 Koumine, an alkaloid extracted from Gelsemium elegans,200 alleviates chondrocyte inflammation by activating Parkin-mediated mitophagy, consequently slowing down the progression of OA.201

Trehalose, a natural disaccharide, demonstrates efficacy in mitigating mitochondrial membrane potential impairment induced by oxidative stress, ATP depletion and DRP1 translocation into the mitochondria.202 Nodakenin (Nod) is one of the main active components in Radix Angelicae biseratae, a traditional Chinese medicine for OA treatment. Research has demonstrated that Nod inhibited DRP1 phosphorylation, thus suppressing ROS generation via DRP1-dependent mitochondrial fission in LPS-stimulated chondrocytes in vitro and attenuated cartilage degradation and inflammation in a mouse OA model.203 Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) intraarticular injection, commonly used for OA treatment,204 has been proven to inhibit mitochondrial damage mediated by LPS through diminishing ROS production, inhibiting DRP1 expression, and upregulating MFN1 expression, eventually repairing mitochondrial function.205

Challenges and future perspectives

Although mitochondrial-targeted delivery of drugs can reduce toxicity and increase therapeutic effectiveness, several challenges remain to be addressed. There are some researches on mitochondrial-targeted delivery of drugs for OA treatments, but few have been tested in clinical settings. To achieve the goal of OA treatment, the drugs or nanocarriers should possess key properties, including chondrocyte or synoviocyte selectivity, activity of an antioxidant or interaction with signaling pathways such as SIRT3/Parkin and AMPK /SIRT1/PGC-1α, etc. By incorporating these properties, the therapeutic compound can restore mitochondrial function, reduce oxidative stress, and ultimately slow down the progression of OA. Therefore, mitochondria-targeting molecules should be carefully selected, as DQA, rhodamine derivatives, KLA peptides and DOX-lipid mentioned above are cytotoxic and more suitable for anticancer therapy. The SS peptides, despite their antioxidant activity, the relatively weaker ability to enter the mitochondrial matrix may limit their application.

There are many options for therapeutic compounds delivered to the mitochondria. In addition to the drugs that interact with mitochondria described above, nanoenzyme and RNA are also promising. This review summarizes the mitochondria-related protein changes and signaling pathways in OA, which may be potential targets to search for appropriate compounds. For example, miR-30 families have been demonstrated to interact with DRP1 in several researches,206,207,208 and it has been confirmed that the expression of miR-30b is upregulated in OA chondrocytes.209 MnO2 as a nanoenzyme has been illustrated to simulate SOD activity and protect cartilage from oxidative stress,210,211 it can also modulate macrophage phenotype and reduce inflammation.212,213

In addition to regulating mitochondria-related proteins and clearing mtROS, targeting mtDNA provides a new idea for OA therapy to improve cell metabolism and anti-inflammatory from the root, especially in the early intervention potential. Mitochondrial replacement technology (MRT) has been reported as a method to prevent severe mitochondrial diseases in newborns with maternal genetic risks by transplanting the nuclear genome from an affected egg to an enucleated donor egg. However, its application between donors and recipients with different haplogroups is not recommended to avoid reversion to affected mtDNA.214 While there has been research suggesting that eggs with random haplogroups can serve as donors,215 the suitability of MRT for preventing degenerative diseases like OA and its ethical issues are still open to debate. RNA-free DddA-derived cytosine base editors (DdCBEs), a base editor specifically converting C-G to T-A in human mtDNA reported by Mok et al.216 may serve as a potential OA prevention method by precise editing of mtDNA. Nevertheless, identifying precise sequence targets for editing and assessing potential side effects remains challenging.

Besides, bare therapeutic compounds may be degraded or inhibited by biomolecules in the cytoplasm. In consequence, nanocarriers can be a promising way to handle this issue. For clinical application, the ideal nanocarrier should have the characteristics of self-assembly, ROS response, and easy preservation. Due to the avascular nature of the joint cavity, the clearance of nanocarriers mainly depends on lymphatic drainage, and larger particles may result in delayed clearance.

Conclusion

In this Review, we have outlined the molecular processes pertaining to the interplay between chondrocyte mitochondria and the onset and progression of OA from diverse perspectives. Recently, organelle targeting has emerged as a promising method for precision drug delivery. Molecular modifications stand out as the primary strategy for mitochondrial targeting, including cations and peptides modification. The common principle of the two methods hinges on taking advantage of the negative mitochondrial membrane potential to attract the positively charged molecules. Additionally, we have highlighted some drugs capable of impacting mitochondria via pathways involving oxidative stress, mitophagy, or mitochondrial dynamics.

In conclusion, mitochondria exert a significant influence on the pathogenesis and progression of OA. Therapeutic strategies targeting mitochondria represent a novel direction in OA treatments. Further exploration of mitochondrial dysfunction’s role in OA pathogenesis and the mechanisms underlying mitochondria-targeted therapies holds the potential to inspire more efficacious treatments for OA patients. In the future, mitochondria targeted therapy is expected to bring better life quality to the majority of OA patients.

References

Martel-Pelletier, J. et al. Osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2, 16072 (2016).

Tong, L. et al. Current understanding of osteoarthritis pathogenesis and relevant new approaches. Bone Res. 10, 60 (2022).

Oliveria, S. A., Felson, D. T., Reed, J. I., Cirillo, P. A. & Walker, A. M. Incidence of symptomatic hand, hip, and knee osteoarthritis among patients in a health maintenance organization. Arthritis Rheum. 38, 1134–1141 (1995).

Sellam, J. & Berenbaum, F. Is osteoarthritis a metabolic disease?. Jt. Bone Spine 80, 568–573 (2013).

Long, H. et al. Prevalence trends of site-specific osteoarthritis from 1990 to 2019: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Arthritis Rheumatol. 74, 1172–1183 (2022).

Blanco, F. J., Rego, I. & Ruiz-Romero, C. The role of mitochondria in osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 7, 161–169 (2011).

Rim, Y. A., Nam, Y. & Ju, J. H. The role of chondrocyte hypertrophy and senescence in osteoarthritis initiation and progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 2358 (2020).

Mobasheri, A. et al. The role of metabolism in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 13, 302–311 (2017).

Zheng, L., Zhang, Z., Sheng, P. & Mobasheri, A. The role of metabolism in chondrocyte dysfunction and the progression of osteoarthritis. Ageing Res. Rev. 66, 101249 (2021).

Maneiro, E. et al. Mitochondrial respiratory activity is altered in osteoarthritic human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 48, 700–708 (2003).

Bernabei, I., So, A., Busso, N. & Nasi, S. Cartilage calcification in osteoarthritis: mechanisms and clinical relevance. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 19, 10–27 (2023).

Fujii, Y. et al. Cartilage homeostasis and osteoarthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 6316 (2022).

Aigner, T., Söder, S., Gebhard, P. M., McAlinden, A. & Haag, J. Mechanisms of disease: role of chondrocytes in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis-structure, chaos and senescence. Nat. Clin. Pr. Rheumatol. 3, 391–399 (2007).

Hashimoto, S. et al. Chondrocyte-derived apoptotic bodies and calcification of articular cartilage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 3094–3099 (1998).

Bertrand, J., Cromme, C., Umlauf, D., Frank, S. & Pap, T. Molecular mechanisms of cartilage remodelling in osteoarthritis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42, 1594–1601 (2010).

Henze, K. & Martin, W. Essence of mitochondria. Nature 426, 127–128 (2003).

Szeto, H. H. & Schiller, P. W. Novel therapies targeting inner mitochondrial membrane-from discovery to clinical development. Pharm. Res. 28, 2669–2679 (2011).

Nunnari J, Suomalainen A. Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell. 148, 1145-1159 (2012).

Wang, P. F. et al. Mitochondrial and metabolic dysfunction of peripheral immune cells in multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroinflamm.21, 28 (2024).

Zhang, L., Wu, J., Zhu, Z., He, Y. & Fang, R. Mitochondrion: a bridge linking aging and degenerative diseases. Life Sci. 322, 121666 (2023).

Battogtokh, G. et al. Mitochondria-targeting drug conjugates for cytotoxic, anti-oxidizing and sensing purposes: current strategies and future perspectives. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 8, 862–880 (2018).

Blanco, F. J., Valdes, A. M. & Rego-Perez, I. Mitochondrial DNA variation and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis phenotypes. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 14, 327–340 (2018).

Lepetsos, P. & Papavassiliou, A. G. ROS/oxidative stress signaling in osteoarthritis. Biochim Biophys. Acta 1862, 576–591 (2016).

Grigolo, B., Roseti, L., Fiorini, M. & Facchini, A. Enhanced lipid peroxidation in synoviocytes from patients with osteoarthritis. J. Rheumatol. 30, 345–347 (2003).

Ostalowska, A. et al. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes in synovial fluid of patients with primary and secondary osteoarthritis of the knee joint. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 14, 139–145 (2006).

Zhao, K. et al. Cell-permeable peptide antioxidants targeted to inner mitochondrial membrane inhibit mitochondrial swelling, oxidative cell death, and reperfusion injury. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34682–34690 (2004).

Ansari, M. Y., Ball, H. C., Wase, S. J., Novak, K. & Haqqi, T. M. Lysosomal dysfunction in osteoarthritis and aged cartilage triggers apoptosis in chondrocytes through BAX mediated release of Cytochrome c. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 29, 100–112 (2021).

Grishko, V. I., Ho, R., Wilson, G. L. & Pearsall, A. W. t. Diminished mitochondrial DNA integrity and repair capacity in OA chondrocytes. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 17, 107–113 (2009).

Valcarcel-Ares, M. N. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction promotes and aggravates the inflammatory response in normal human synoviocytes. Rheumatology 53, 1332–1343 (2014).

Wang, C. & Youle, R. J. The role of mitochondria in apoptosis*. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 95–118 (2009).

Zhang, J., Hao, X., Chi, R., Qi, J. & Xu, T. Moderate mechanical stress suppresses the IL-1beta-induced chondrocyte apoptosis by regulating mitochondrial dynamics. J. Cell Physiol. 236, 7504–7515 (2021).

Fu, Y. et al. Aging promotes Sirtuin 3-Dependent Cartilage Superoxide Dismutase 2 Acetylation and Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68, 1887–1898 (2016).

Liu, M. et al. Insights into manganese superoxide dismutase and human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 15893 (2022).

Scott, J. L. et al. Superoxide dismutase downregulation in osteoarthritis progression and end-stage disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 1502–1510 (2010).

Ruiz-Romero, C. et al. Mitochondrial dysregulation of Osteoarthritic human articular chondrocytes analyzed by proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 8, 172–189 (2009).

Fernandez-Moreno, M. et al. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups and serum levels of anti-oxidant enzymes in patients with osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 12, 264 (2011).

D’Aquila, P., Rose, G., Panno, M. L., Passarino, G. & Bellizzi, D. SIRT3 gene expression: a link between inherited mitochondrial DNA variants and oxidative stress. Gene 497, 323–329 (2012).

Koike, M. et al. Mechanical overloading causes mitochondrial superoxide and SOD2 imbalance in chondrocytes resulting in cartilage degeneration. Sci. Rep. 5, 11722 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. Tumour suppressor SIRT3 deacetylates and activates manganese superoxide dismutase to scavenge ROS. EMBO Rep. 12, 534–541 (2011).

Onyango, P., Celic, I., McCaffery, J. M., Boeke, J. D. & Feinberg, A. P. SIRT3, a human SIR2 homologue, is an NAD-dependent deacetylase localized to mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13653–13658 (2002).

Qiu, X., Brown, K., Hirschey, M. D., Verdin, E. & Chen, D. Calorie restriction reduces oxidative stress by SIRT3-mediated SOD2 activation. Cell Metab. 12, 662–667 (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Reprogramming of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex by targeting SIRT3-COX4I2 axis attenuates osteoarthritis progression. Adv. Sci.10, e2206144 (2023).

Yu, W., Dittenhafer-Reed, K. E. & Denu, J. M. SIRT3 protein deacetylates isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2) and regulates mitochondrial redox status. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 14078–14086 (2012).

Da, W., Chen, Q. & Shen, B. The current insights of mitochondrial hormesis in the occurrence and treatment of bone and cartilage degeneration. Biol. Res. 57, 37 (2024).

Zhang, X., Li, H., Chen, L., Wu, Y. & Li, Y. NRF2 in age-related musculoskeletal diseases: Role and treatment prospects. Genes Dis. 11, 101180 (2024).

Wang, P. et al. Macrophage achieves self-protection against oxidative stress-induced ageing through the Mst-Nrf2 axis. Nat. Commun. 10, 755 (2019).

Lv, Z. TRPV1 alleviates osteoarthritis by inhibiting M1 macrophage polarization via Ca2+/CaMKII/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 12, 504 (2021).

Sanada, Y., Tan, S. J. O., Adachi, N. & Miyaki, S. Pharmacological Targeting of Heme Oxygenase-1 in Osteoarthritis. Antioxidants 10, 419 (2021).

Khan, N. M., Ahmad, I. & Haqqi, T. M. Nrf2/ARE pathway attenuates oxidative and apoptotic response in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes by activating ERK1/2/ELK1-P70S6K-P90RSK signaling axis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 116, 159–171 (2018).

Fernández, P., Guillén, M. I., Gomar, F. & Alcaraz, M. J. Expression of heme oxygenase-1 and regulation by cytokines in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Biochem. Pharm. 66, 2049–2052 (2003).

Alcaraz, M. J. & Ferrándiz, M. L. Relevance of Nrf2 and heme oxygenase-1 in articular diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 157, 83–93 (2020).

Takada, T. et al. Bach1 deficiency reduces severity of osteoarthritis through upregulation of heme oxygenase-1. Arthritis Res Ther. 17, 285 (2015).

Shi, Y. et al. Tangeretin suppresses osteoarthritis progression via the Nrf2/NF-κB and MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathways. Phytomedicine 98, 153928 (2022).

Murata, H. et al. NRF2 Regulates PINK1 expression under oxidative stress conditions. PLoS One 10, e0142438 (2015).

Hou, L. et al. Mitoquinone alleviates osteoarthritis progress by activating the NRF2-Parkin axis. iScience 26, 107647 (2023).

Gumeni, S., Papanagnou, E. D., Manola, M. S. & Trougakos, I. P. Nrf2 activation induces mitophagy and reverses Parkin/Pink1 knock down-mediated neuronal and muscle degeneration phenotypes. Cell Death Dis. 12, 671 (2021).

Sabouny, R. et al. The Keap1-Nrf2 stress response pathway promotes mitochondrial hyperfusion through degradation of the mitochondrial Fission Protein Drp1. Antioxid. Redox Signal 27, 1447–1459 (2017).

Ansari, M. Y., Novak, K. & Haqqi, T. M. ERK1/2-mediated activation of DRP1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and apoptosis in chondrocytes. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 30, 315–328 (2022).

Piantadosi, C. A., Carraway, M. S., Babiker, A. & Suliman, H. B. Heme oxygenase-1 regulates cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis via Nrf2-mediated transcriptional control of nuclear respiratory factor-1. Circ. Res. 103, 1232–1240 (2008).

Rhodes, M. A. et al. Carbon monoxide, skeletal muscle oxidative stress, and mitochondrial biogenesis in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297, H392–399 (2009).

Xiao, Y. & Zhang, L. Mechanistic and therapeutic insights into the function of NLRP3 inflammasome in sterile arthritis. Front. Immunol. 14, 1273174 (2023).

Jia, L. et al. Ginkgolide C inhibits ROS-mediated activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in chondrocytes to ameliorate osteoarthritis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 325, 117887 (2024).

Sun, H. et al. Blocking TRPV4 Ameliorates Osteoarthritis by Inhibiting M1 Macrophage Polarization via the ROS/NLRP3 Signaling Pathway. Antioxidants11, 2315 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Inhibition of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling leads to increased activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 21, 300 (2019).

Lin, Y. et al. Gallic acid alleviates gouty arthritis by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis through enhancing Nrf2 signaling. Front. Immunol. 11, 580593 (2020).

Dai, T. et al. SCP2 mediates the transport of lipid hydroperoxides to mitochondria in chondrocyte ferroptosis. Cell Death Discov. 9, 234 (2023).

Wu, X. et al. Kindlin-2 preserves integrity of the articular cartilage to protect against osteoarthritis. Nat. Aging 2, 332–347 (2022).

Shang, J. et al. Inhibition of Klf10 attenuates oxidative stress-induced senescence of chondrocytes via modulating mitophagy. Molecules 28, 924 (2023).

Shu, L. et al. ATAD3B is a mitophagy receptor mediating clearance of oxidative stress-induced damaged mitochondrial DNA. EMBO J. 40, e106283 (2021).

Schiavi, A. et al. Iron-starvation-induced mitophagy mediates lifespan extension upon mitochondrial stress in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 25, 1810–1822 (2015).

Sun, K., Jing, X., Guo, J., Yao, X. & Guo, F. Mitophagy in degenerative joint diseases. Autophagy 17, 2082–2092 (2021).

Vives-Bauza, C. et al. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 378–383 (2010).

Wang, Y., Nartiss, Y., Steipe, B., McQuibban, G. A. & Kim, P. K. ROS-induced mitochondrial depolarization initiates PARK2/PARKIN-dependent mitochondrial degradation by autophagy. Autophagy 8, 1462–1476 (2012).

Liu, L. et al. Mitochondrial outer-membrane protein FUNDC1 mediates hypoxia-induced mitophagy in mammalian cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 177–185 (2012).

Clark, I. E. et al. Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature 441, 1162–1166 (2006).

Jin, S. M. et al. Mitochondrial membrane potential regulates PINK1 import and proteolytic destabilization by PARL. J. Cell Biol. 191, 933–942 (2010).

Yamano, K. & Youle, R. J. PINK1 is degraded through the N-end rule pathway. Autophagy 9, 1758–1769 (2013).

Geisler, S. et al. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 119–131 (2010).

Gegg, M. E. et al. Mitofusin 1 and mitofusin 2 are ubiquitinated in a PINK1/parkin-dependent manner upon induction of mitophagy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 4861–4870 (2010).

Youle, R. J. & Narendra, D. P. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 9–14 (2011).

Nguyen, T. N., Padman, B. S. & Lazarou, M. Deciphering the molecular signals of PINK1/Parkin Mitophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 26, 733–744 (2016).

Zhang, C. et al. Oxidative stress-induced mitophagy is suppressed by the miR-106b-93-25 cluster in a protective manner. Cell Death Dis. 12, 209 (2021).

Ansari, M. Y., Khan, N. M., Ahmad, I. & Haqqi, T. M. Parkin clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria regulates ROS levels and increases survival of human chondrocytes. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 26, 1087–1097 (2018).

Dai, Y., Hu, X. & Sun, X. Overexpression of parkin protects retinal ganglion cells in experimental glaucoma. Cell Death Dis. 9, 88 (2018).

Shin, H. J. et al. Pink1-mediated chondrocytic mitophagy contributes to cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritis. J. Clin. Med. 8, 1849 (2019).

Wei, T. et al. Sirtuin 3 deficiency accelerates hypertensive cardiac remodeling by impairing angiogenesis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6, e006114 (2017).

Wang, C. et al. Protective effects of metformin against osteoarthritis through upregulation of SIRT3-mediated PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy in primary chondrocytes. Biosci. Trends 12, 605–612 (2019).

Xin, R. et al. Mitochonic Acid-5 inhibits reactive oxygen species production and improves human chondrocyte survival by upregulating SIRT3-mediated, Parkin-dependent Mitophagy. Front. Pharm. 13, 911716 (2022).

Yuan, Y. et al. alpha-Ketoglutaric acid ameliorates hyperglycemia in diabetes by inhibiting hepatic gluconeogenesis via serpina1e signaling. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn2879 (2022).

Liu, L. et al. The physiological metabolite alpha-ketoglutarate ameliorates osteoarthritis by regulating mitophagy and oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 62, 102663 (2023).

Novak, I. et al. Nix is a selective autophagy receptor for mitochondrial clearance. EMBO Rep. 11, 45–51 (2010).

An, F. et al. New insight of the pathogenesis in osteoarthritis: the intricate interplay of ferroptosis and autophagy mediated by mitophagy/chaperone-mediated autophagy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 1297024 (2023).

Sowter, H. M., Ratcliffe, P. J., Watson, P., Greenberg, A. H. & Harris, A. L. HIF-1-dependent regulation of hypoxic induction of the cell death factors BNIP3 and NIX in human tumors. Cancer Res. 61, 6669–6673 (2001).

Hu, S. et al. Stabilization of HIF-1alpha alleviates osteoarthritis via enhancing mitophagy. Cell Death Dis. 11, 481 (2020).

Kim, D., Song, J. & Jin, E. J. BNIP3-Dependent mitophagy via PGC1alpha promotes cartilage degradation. Cells 10, 1839 (2021).

Chan, D. C. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in mammals. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 79–99 (2006).

Wang, F. S. et al. Irisin mitigates oxidative stress, chondrocyte dysfunction and osteoarthritis development through regulating mitochondrial integrity and autophagy. Antioxidants 9, 810 (2020).

Yan, Z. et al. TRPV4-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction induces pyroptosis and cartilage degradation in osteoarthritis via the Drp1-HK2 axis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 123, 110651 (2023).

Lin, Z. et al. Chondrocyte-targeted exosome-mediated delivery of Nrf2 alleviatescartilaginous endplate degeneration by modulating mitochondrial fission. J.Nanobiotechnol. 22, 281 (2024).

Hu, S. L. et al. TBK1-medicated DRP1 phosphorylation orchestrates mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy activation in osteoarthritis. Acta Pharm. Sin. 44, 610–621 (2023).

He, J. et al. Upregulated mitochondrial dynamics is responsible for the procatabolic changes of chondrocyte induced by alpha2-Adrenergic signal activation. Cartilage, 19476035231189841 (2023).

Gao, S. & Hu, J. Mitochondrial fusion: the machineries in and out. Trends Cell Biol. 31, 62–74 (2021).

Samant, S. A. et al. SIRT3 deacetylates and activates OPA1 to regulate mitochondrial dynamics during stress. Mol. Cell Biol. 34, 807–819 (2014).

Madhu, V. et al. OPA1 protects intervertebral disc and knee joint health in aged mice by maintaining the structure and metabolic functions of mitochondria. bioRxiv (2024).

Xu, L. et al. MFN2 contributes to metabolic disorders and inflammation in the aging of rat chondrocytes and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 28, 1079–1091 (2020).

Yu, M., Wang, D., Chen, X., Zhong, D. & Luo, J. BMSCs-derived Mitochondria Improve Osteoarthritis by ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction and promoting mitochondrial biogenesis in chondrocytes. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 18, 3092–3111 (2022).

Deng, X. et al. Moderate mechanical strain and exercise reduce inflammation and excessive autophagy in osteoarthritis by downregulating mitofusin 2. Life Sci. 332, 122020 (2023).

Moqbel, S. A. A. et al. The effect of mitochondrial fusion on chondrogenic differentiation of cartilage progenitor/stem cells via Notch2 signal pathway. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 13, 127 (2022).

Yao, Q. et al. Osteoarthritis: pathogenic signaling pathways and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 8, 56 (2023).

Zong, H. et al. AMP kinase is required for mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle in response to chronic energy deprivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 15983–15987 (2002).

Terkeltaub, R., Yang, B., Lotz, M. & Liu-Bryan, R. Chondrocyte AMP-activated protein kinase activity suppresses matrix degradation responses to proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor α. Arthritis Rheum. 63, 1928–1937 (2011).

Ge, Y. et al. Estrogen prevents articular cartilage destruction in a mouse model of AMPK deficiency via ERK-mTOR pathway. Ann. Transl. Med. 7, 336 (2019).

Zhou, Y. et al. Berberine prevents nitric oxide-induced rat chondrocyte apoptosis and cartilage degeneration in a rat osteoarthritis model via AMPK and p38 MAPK signaling. Apoptosis 20, 1187–1199 (2015).

Li, J. et al. Metformin limits osteoarthritis development and progression through activation of AMPK signalling. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 79, 635–645 (2020).

Chen, L. Y., Wang, Y., Terkeltaub, R. & Liu-Bryan, R. Activation of AMPK-SIRT3 signaling is chondroprotective by preserving mitochondrial DNA integrity and function. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 26, 1539–1550 (2018).

Du, X. et al. TGF-beta3 mediates mitochondrial dynamics through the p-Smad3/AMPK pathway. Cell Prolif. 57, e13579 (2023).

Landry, J. et al. The silencing protein SIR2 and its homologs are NAD-dependent protein deacetylases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5807–5811 (2000).

Haigis, M. C. & Sinclair, D. A. Mammalian sirtuins: biological insights and disease relevance. Annu Rev. Pathol. 5, 253–295 (2010).

Chen, H. et al. Inhibition of the lncRNA 585189 prevents podocyte injury and mitochondria dysfunction by promoting hnRNP A1 and SIRT1 in diabetic nephropathy. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 578, 112065 (2023).

Jin, T. et al. Exosomes derived from diabetic serum accelerate the progression of osteoarthritis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 755, 109960 (2024).

Kan, S. et al. FGF19 increases mitochondrial biogenesis and fusion in chondrocytes via the AMPKα-p38/MAPK pathway. Cell Commun. Signal 21, 55 (2023).

Wang, Y., Zhao, X., Lotz, M., Terkeltaub, R. & Liu-Bryan, R. Mitochondrial biogenesis is impaired in osteoarthritis chondrocytes but reversible via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1alpha. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 2141–2153 (2015).

Sun, J. et al. Sestrin2 overexpression attenuates osteoarthritis pain via induction of AMPK/PGC-1alpha-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis and suppression of neuroinflammation. Brain Behav. Immun. 102, 53–70 (2022).

Torroni, A. et al. Classification of European mtDNAs from an analysis of three European populations. Genetics 144, 1835–1850 (1996).

Marcuello, A. et al. Human mitochondrial variants influence on oxygen consumption. Mitochondrion 9, 27–30 (2009).

Martinez-Redondo, D. et al. Human mitochondrial haplogroup H: the highest VO2max consumer-is it a paradox?. Mitochondrion 10, 102–107 (2010).

Fernandez-Moreno, M. et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups influence the risk of incident knee osteoarthritis in OAI and CHECK cohorts. A meta-analysis and functional study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 1114–1122 (2017).

Fernandez-Moreno, M. et al. mtDNA haplogroup J modulates telomere length and nitric oxide production. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 12, 283 (2011).

Piskór, B. M., Przylipiak, A., Dąbrowska, E., Niczyporuk, M. & Ławicki, S. Matrilysins and Stromelysins in Pathogenesis and Diagnostics of Cancers. Cancer Manag. Res. 12, 10949–10964 (2020).

Hu, Q. & Ecker, M. Overview of MMP-13 as a Promising Target for the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Int J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1742 (2021).

Shi, J., Zhang, C., Yi, Z. & Lan, C. Explore the variation of MMP3, JNK, p38 MAPKs, and autophagy at the early stage of osteoarthritis. IUBMB Life 68, 293–302 (2016).

Qiu, L., Luo, Y. & Chen, X. Quercetin attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction and biogenesis via upregulated AMPK/SIRT1 signaling pathway in OA rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 103, 1585–1591 (2018).

Rego-Pérez, I. et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups and serum levels of proteolytic enzymes in patients with osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 646–652 (2011).

Rego-Pérez, I. et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups modulate the serum levels of biomarkers in patients with osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 910–917 (2010).

Rego-Perez, I., Fernandez-Moreno, M., Fernandez-Lopez, C., Arenas, J. & Blanco, F. J. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups: role in the prevalence and severity of knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 2387–2396 (2008).

Rego, I. et al. Role of European mitochondrial DNA haplogroups in the prevalence of hip osteoarthritis in Galicia, Northern Spain. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 210–213 (2010).

Soto-Hermida, A. et al. mtDNA haplogroups and osteoarthritis in different geographic populations. Mitochondrion 15, 18–23 (2014).

Shen, J. M., Feng, L. & Feng, C. Role of mtDNA haplogroups in the prevalence of osteoarthritis in different geographic populations: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 9, e108896 (2014).

Fang, H. et al. Role of mtDNA haplogroups in the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in a southern Chinese population. Int J. Mol. Sci. 15, 2646–2659 (2014).

Fang, H. et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups modify the risk of osteoarthritis by altering mitochondrial function and intracellular mitochondrial signals. Biochim Biophys. Acta 1862, 829–836 (2016).

Koo, B. S. et al. Association of Asian mitochondrial DNA haplogroup B with new development of knee osteoarthritis in Koreans. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 22, 411–416 (2019).

Rego-Pérez, I. et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups associated with MRI-detected structural damage in early knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 26, 1562–1569 (2018).

Soto-Hermida, A. et al. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups influence the progression of knee osteoarthritis. Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI). PLoS One 9, e112735 (2014).

Zhao, Z. et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups participate in osteoarthritis: current evidence based on a meta-analysis. Clin. Rheumatol. 39, 1027–1037 (2020).

Durán-Sotuela, A. et al. Mitonuclear epistasis involving TP63 and haplogroup UK: risk of rapid progression of knee OA in patients from the OAI. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 32, 526-534 (2024).

Gyimesi, G. & Hediger, M. A. Transporter-mediated drug delivery. Molecules 28, 1151 (2023).

Yuan, H., Li, J., Bao, G. & Zhang, S. Variable nanoparticle-cell adhesion strength regulates cellular uptake. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 138101 (2010).

Morici, L., Allémann, E., Rodríguez-Nogales, C. & Jordan, O. Cartilage-targeted drug nanocarriers for osteoarthritis therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 666, 124843 (2024).

Zheng, L. et al. Primary chondrocyte exosomes mediate osteoarthritis progression by regulating mitochondrion and immune reactivity. Nanomedicine14, 3193–3212 (2019).

Kim, H. R. et al. Fusogenic liposomes encapsulating mitochondria as a promising delivery system for osteoarthritis therapy. Biomaterials 302, 122350 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Pioglitazone-loaded cartilage-targeted nanomicelles (Pio@C-HA-DOs) for osteoarthritis treatment. Int. J. Nanomed. 18, 5871–5890 (2023).

Saminathan, A., Zajac, M., Anees, P. & Krishnan, Y. Organelle-level precision with next-generation targeting technologies. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 355–371 (2021).

Zielonka, J. et al. Mitochondria-targeted triphenylphosphonium-based compounds: syntheses, mechanisms of action, and therapeutic and diagnostic applications. Chem. Rev. 117, 10043–10120 (2017).

Ross, M. F. et al. Lipophilic triphenylphosphonium cations as tools in mitochondrial bioenergetics and free radical biology. Biochemistry 70, 222–230 (2005).

Ketterer, B., Neumcke, B. & Läuger, P. Transport mechanism of hydrophobic ions through lipid bilayer membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 5, 225–245 (1971).

Liberman, E. A., Topaly, V. P., Tsofina, L. M., Jasaitis, A. A. & Skulachev, V. P. Mechanism of coupling of oxidative phosphorylation and the membrane potential of mitochondria. Nature 222, 1076–1078 (1969).

Wang, J. Y., Li, J. Q., Xiao, Y. M., Fu, B. & Qin, Z. H. Triphenylphosphonium (TPP)-based antioxidants: a new perspective on antioxidant design. ChemMedChem 15, 404–410 (2020).

Fan, L. et al. Exosome-based mitochondrial delivery of circRNA mSCAR alleviatessepsis by orchestrating macrophage activation. Adv. Sci. 10, e2205692 (2023).

Lei, X. et al. Mitochondrial calcium nanoregulators reverse the macrophage proinflammatory phenotype through restoring mitochondrial calcium homeostasis for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Int. J. Nanomed. 18, 1469–1489 (2023).

Bailly, C. Medicinal applications and molecular targets of dequalinium chloride. Biochem Pharm. 186, 114467 (2021).

Gaspar, C. et al. Dequalinium chloride effectively disrupts bacterial Vaginosis (BV) Gardnerella spp. Biofilms. Pathogens 10, 261 (2021).

Bae, Y. et al. Dequalinium-based functional nanosomes show increased mitochondria targeting and anticancer effect. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 124, 104–115 (2018).