Abstract

Introduction Smoking is a major contributor to health inequalities in the UK. The ENHANCE-D trial is evaluating three smoking cessation interventions (nicotine replacement therapy [NRT], electronic cigarettes [ECs] or ‘very brief advice') delivered in NHS primary dental care. This qualitative study aimed to provide insight into the factors that could influence the adoption of the interventions in these settings.

Methods Interviews were conducted at two timepoints. Purposive maximum variation sampling was used to recruit and interview a total of 24 dental patients, 12 dental professionals and three NHS dental commissioners. Thematic analysis was carried out using normalisation process theory as an analytical framework.

Results Dental settings were perceived as an appropriate location to deliver smoking cessation interventions. Patients had several motivating and demotivating factors regarding use of NRTs or ECs; they often had negative preconceptions. Financial considerations were major influencers for both patients and dental teams. The time pressures for dental practices were identified as a major barrier. Some practical issues, such as procurement and stock supply, would need to be considered if the ENHANCE-D interventions were to be implemented in routine practice.

Conclusion Primary dental care teams are well-placed to deliver smoking cessation interventions. However, a number of facilitators and deterrents have been identified and strategic changes are needed for successful implementation.

Key points

-

This paper provides insight into the factors that could influence the adoption of two smoking cessation interventions (nicotine replacement therapy and electronic cigarettes) in addition to very brief advice in NHS dental practices.

-

Dental patients, professionals and commissioners consider NHS dental practices to be a strategic and viable place to offer smoking cessation interventions.

-

Pragmatic changes to NHS dental regulations and contracts are needed to accommodate smoking cessation interventions in routine primary care dentistry.

-

This study provides qualitative evidence to compliment clinical findings from the wider ENHANCE-D trial which may inform policy development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smoking is a major contributor to health inequalities in the UK1 and is independently associated with reduced oral health-related quality of life.2 Severe periodontitis is a leading cause of tooth loss among UK adults and smoking is the biggest risk factor for periodontitis development and its progression.3,4Smokers have poorer responses to periodontal treatment3 and smokers who attend dental appointments are more likely than non-smokers to be found to be having trouble with their teeth or dentures.5 These symptoms can be used as powerful prompts - a ‘teachable moment' - for a quit attempt.

Since 2007, multiple editions of Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention (DBOH)6 and other focused resources7 have provided support for dental professionals (DPs) to deliver high-quality preventive care. This includes asking about smoking status and options for smoking cessation. DBOH advises that DPs should support smoking cessation conversations through a ‘very brief advice' (VBA) approach. This has been shown to double a patient's success with quitting smoking.8 VBA is designed to be delivered in under 30 seconds, following the 3A approach (ask, advise, act), typically resulting in signposting to a local pharmacy, stop smoking services or general practitioner.6 This is very much in keeping with the Making Every Contact Count agenda,9 which focuses on the millions of day-to-day interactions that organisations and individuals have to support people to improve their lifestyle and look after their wellbeing and mental health through lifestyle changes, such as stopping smoking.9

Dental teams are potentially well-placed to offer more intensive smoking cessation interventions. For example, they are one of the few healthcare settings that asymptomatic patients regularly attend. There is moderate-certainty evidence from clinical trials that DPs can achieve further improved quit rates by offering behavioural support combined with provision of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or electronic cigarettes (ECs).8 However, there are several potential barriers to dental teams delivering effective smoking cessation interventions. The most cited barriers include: a lack of time; training; perceived interest by patients; and remuneration.10,11

The ENHANCE-D study is a clinical trial that aims to evaluate the clinical- and cost-effectiveness and safety of three enhanced interventions (NRT or EC starter kit), each combined with a single-visit behavioural intervention in NHS primary dental care settings. Dental team members (dental nurse, dental hygienist, dental therapist or dentist) received pragmatic training in the smoking cessation interventions. They were required to complete four existing training packages available through the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT). As part of study-specific training sessions, dental teams were given brief guidance on adapting the standard NCSCT training into a single-visit behavioural intervention.

This study is a qualitative evaluation of the ENHANCE-D trial to explore experiences from a range of stakeholder perspectives that have the potential to influence adoption of the proposed interventions in NHS primary dental care. In this study, patients' perceptions of the EC and NRT interventions compared to usual care (VBA) were sought, alongside DPs' perceptions of facilitators and barriers to provision of these interventions within the NHS. A third participant group comprised NHS commissioners and service managers who have responsibility for commissioning appropriate local dental services. This study aims to provide insight into each intervention's acceptability, as well as issues with implementation, and regulatory and NHS service considerations.

Methods

This qualitative study is a component of the wider ENHANCE-D clinical trial funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme (project reference number: NIHR129780). The trial is registered with the following references: IRAS 1004761; EudraCT 2021-005440-30; NHS REC 22/NE/0040; ISRCTN 13158982. The trial is a pragmatic, multi-centre, definitive, open-label, three-arm, parallel group, individually randomised controlled superiority trial, with the aim to recruit dental patients from 56 NHS primary dental care settings across seven UK regional hubs (Newcastle, Sheffield, Birmingham, Plymouth, Dundee, Glasgow and Edinburgh).

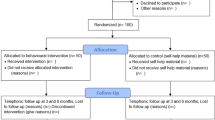

The analytical framework for this qualitative study draws on normalisation process theory (NPT) which helps to understand how actions and practices become embedded and integrated into their social context.12 Purposive maximum variation sampling (ie patients were selected based on their age, sex, location and intervention arm to ensure variation within interviewees) was used to recruit patients from all trial arms, DPs from the dental practices at which the interventions were delivered, and commissioners from different geographical regions of the UK. Selected participants for this study were invited to participate in a qualitative interview at both one-month and six-month time points (relative to randomisation) (Fig. 1). Participants were offered a choice of face-to-face, online or telephone interviews, or focus groups with other participants. Topic guides were constructed by the researchers based upon the research aims and NPT constructs (see online Supplementary Information). A participation information sheet was issued to all potential participants and written informed consent was obtained for all participants in line with the study's ethical approval (see IRAS and NHS REC reference above). Participants were informed that their names would not be used in any published findings or other study dissemination. All interviews were audio-recorded either by Zoom cloud recording or an external recording device (for telephone interviews) and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription company. Transcripts were imported into NVivo software (Lumivero, Version 13, released March 2020).

The qualitative element of the wider ENHANCE-D randomised clinical trial. Flowchart illustrates the timing of qualitative interventions with various participant groups. For patients, qualitative data was collected approximately one month following intervention start (early) and at approximately six months following intervention start (late)

The research team analysed the data using thematic analysis to identify data-driven themes and subthemes. RDH reviewed the initial themes with AW before validation of the themes, carried out by consensus in a meeting between the authors. The themes were presented in relation to their fit with the NPT constructs (coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring).

In NPT, ‘coherence' relates to ensuring comprehension among people involved in its implementation of the need for an intervention and its constituent parts. ‘Cognitive participation' describes the relationship between those involved in implementing an intervention and helps them understand how they can invest commitment and ownership in the intervention. ‘Collective action' describes the interaction between implementers (ie DPs) and recipients (ie smokers/patients), the work they do to make the intervention function, and the need to maintain confidence in their activities. ‘Reflexive monitoring' describes how implementers assess the impact of an intervention, identifying its worth individually and collectively using formal and informal avenues.12

Results

All interviews were conducted either online via Zoom or by telephone; no participants selected a focus group setting. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of those interviewed in this study. In total, 24 patients, 13 DPs and three NHS commissioners/managers were interviewed by AW between November 2022 and August 2023.

As indicated above, NPT was used as a framework to explore the social organisation and the interplay of factors associated with the implementation of the ENHANCE-D trial and its interventions. Therefore, the results are presented thematically and associated with four NPT constructs (Table 2).

Coherence

In this study, coherence explained the motivating factors for smoking cessation interventions ie what patients envisage to be the potential benefits thereof. Patients identified a financial motivation to quit smoking:

-

‘It's expensive to smoke…it's cheaper to vape' (patient, male, 18-34 years, NRT, Newcastle).

Patients were also motivated to quit smoking using the interventions delivered by dental and general health considerations:

-

‘Just having the EC is more beneficial and less harmful for my health than having cigarettes' (patient, female, 55+ yrs, EC, Birmingham).

Patients perceived the interventions not only as less risky, but also a more convenient and more psychologically effective substitute for smoking. For instance:

-

‘It's not obvious [NRT patch]. Slap it on in the morning and you don't have to think about it all day' (patient, female, 35-54 yrs, NRT, Dundee)

-

‘I was more up to it [EC] because it would mimic the real thing but then I can psychologically push the real thing out and keep that one' (patient, female, 35-54 yrs, NRT, Birmingham).

Despite the motivations to quit smoking already mentioned, some patients still needed to have an intrinsic motivation or be mentally ready to quit before they could accept the interventions offered:

-

‘People don't want to stop smoking unless you've decided to stop smoking' (patient, male, 18-34 yrs, NRT, Newcastle).

Although some patients had both intrinsic (within a person) and extrinsic (external factors) motivations to quit smoking, they became demotivated if they were randomised to an arm of the trial that did not match with their views on what they wanted to use to stop smoking:

-

‘The majority of the ones that have been quite excited about it have obviously been the ones who have been randomised to NRT or e-cig…which seems to have a more positive effect than the two people that we've just done the very brief interventions with the advice…and it's almost like they're like, “oh well, yeah, I kind of knew that” and they go away' (dental nurse, Scotland).

Cognitive participation

In this study, cognitive participation explained two implementation considerations: the benefits of smoking cessation interventions in NHS primary care settings and patient demotivators towards the interventions.

All stakeholders interviewed shared similar views that dental appointments provide a unique opportunity for DPs to discuss and potentially implement smoking cessation interventions. However, one commissioner also acknowledged that demands upon the funding of NHS dental services is often subject to tensions and competing priorities. This may potentially limit the availability and provision of certain smoking cessation interventions in dentistry (particularly NRT- and EC-based interventions). These issues are exemplified in the statements from a dentist and commissioner:

-

‘People come and see their dentist on a six-monthly basis, and you're in a great position to have those conversations with people. I cannot remember the last time I saw my GP…so, if I was a smoker, I would have no exposure to anyone telling me to stop' (dentist, Northern England)

-

‘So, in terms of using dentists to provide services regarding smoking cessation or anything else, I think it's a fantastic idea. But of course, if they're only seeing - or funded to see - 50% of the population…then we're probably getting to about 30% of the population that they see. And possibly half of those might be children. However, even those people they do see, it's an absolutely great idea to capture those patients' (NHS commissioner, Southern England).

NHS commissioners, DPs and patients also shared the view that receiving smoking cessation interventions from DPs has the potential to be viable because smoking-related oral health problems are relatable to patients who can see the aesthetic value of stopping smoking. All participant groups acknowledged this point:

-

‘I think we can get quite a high success rate of smoking cessation…patients quite often don't really care that they're going to die of smoking strangely enough. But actually, if they're going to lose all their teeth because of smoking, that can sometimes be more immediate, if you like' (NHS commissioner, Scotland)

-

‘Because of the effect smoking has on your gums, on your teeth, obviously we are a good profession to be able to give that advice and to be able to show patients the effect of smoking…in the dental practice, you can say, “right, look in this mirror, look at your gums, look at the staining. This is the effect of smoking”' (dentist, Midlands)

-

‘You can make a direct correlation between the benefits of it and what could go wrong if you were to carry on, in terms of something like, your mouth is a very prominent area of your body, you know, everybody's really conscious about it' (patient, female, 35-54 yrs, NRT, Dundee).

With respect to the patient demotivators regarding using EC and NRT as an aid to stop smoking, some patients reported that they struggled to cope with stress without using cigarettes, they had negative sentiments towards and negative experiences of using smoking cessation interventions, and an unwillingness to pay for the interventions. Some patients, from both the NRT and EC arms, who were attempting to quit smoking found themselves occasionally returning to smoking as a coping strategy when faced with stressful life events. Patients who received the NRT and EC interventions expressed the opinion that if patients were to pay for the interventions in a dental practice, they would be less likely to use them to quit smoking:

-

‘I was doing really well, and then over the weekend I failed and started smoking again…due to my cat, dying, unexpectedly' (patient, male,18-34 yrs, NRT, Dundee)

-

‘I think everything's more attractive to people if it's free…people would be less likely to pay out their own pocket for it [EC]' (patient, female, 35-54 yrs, EC, Glasgow).

Misinformation about the safety of ECs underpinned negative perceptions of the intervention among some patients. Other patients described weight gain and other side effects of the interventions as deterring them from continued engagement with the intervention:

-

‘I think a lot of people are put off using ECs because of all the advertising at the beginning saying they were worse than cigarettes, they're bad for your health' (patient, female, 55+ yrs, EC, Sheffield)

-

‘I probably wouldn't choose the patches again though because they play a bit of havoc with like, my heart rate and I was getting some really crazy dreams with them' (patient, female, 35-54 yrs, NRT, Dundee)

-

‘But there is that combination of giving up smoking. I think anybody you speak to who has smoked, will tell you that they have, when they've given up, they've put on a lot of weight' (patient, female, 55+ yrs, NRT, Newcastle).

Collective action

A common issue among DPs was the time constraint to accommodate giving ENHANCE-D interventions within routine dental care. As one dental professional mentioned:

-

‘It's not something that we can deliver within clinical time and still stick to time' (dental nurse, Scotland).

Some of the highlighted time constraints were research-related ie given that the interventions were offered as part of a clinical trial, there were research-related procedures and documentation that required additional time to administer:

-

‘Most people aren't going to be able to find that many hours [of] free time to go through a load of smoking cessation advice, that is a bit overkill for a dentist…and then there's the prescription ordering, there's the logging it…it doubles the time you have to spend with patients which I think in busy-it would, in busy practices, is going to be a major no no' (dentist, Southern England).

Perceptions of limited time to undertake certain smoking cessation interventions were frequently associated with remuneration concerns. Dental practices are businesses, and, in England, NHS practices must generate units of dental activity (UDAs) in order to meet their annual contractual obligations. Therefore, DPs working within the NHS in England arguably need to prioritise clinical activity that generates UDAs and financial income. One of the DPs summarised this scenario:

-

‘Reduced capacity to provide units of dental activity for your NHS contract…the more time you spend delivering your intervention, the less time you are earning money…there would need to be some sort of financial incentive to cover the time spent doing that, and I think that would be the biggest thing' (dentist, Northern England).

Reflexive monitoring

Commissioners felt the need for a training programme for dental staff to equip them to administer EC and NRT interventions effectively. Commissioners also expressed concerns about the logistics of product (NRT or EC) delivery to dental practices as adopted by the ENHANCE-D trial:

-

‘It's a difficult question, saying to somebody, “have you thought about giving up smoking?” …so, the first thing will be training…so you can't just say to them, provide this information…that is a difficult conversation so use like some form of mentorship…so, there's a big training programme behind this' (NHS commissioner, Southern England)

-

‘I mean, there's very basic things like getting the stock out to them and who would do that and, if it was ECs for example, how would they be procured? How would you even choose which one you would use? How would you make sure it was safe and all that kind of stuff?' (NHS commissioner, Scotland).

Commissioners and DPs perceived the current regulatory framework in NHS dentistry as potentially constraining the viability of EC and NRT interventions in primary dental care settings:

-

‘The problem and constraint we have in primary care is that the current regulatory system and the way that the system of commissioning works is not really patient-centred. Again, this is a personal view, it's not really patient-centred, it's not really holistic care-focused. It's very much about delivering activity and payment for activity' (NHS commissioner, Northern England)

-

‘There would have been an immediate barrier with the old contract that the dentist would have immediately said “I'm not paid to deliver that”. Whereas now you could-I'm hoping what will come out is there would be time allocated for prevention so there wouldn't be that barrier of the dentist being able to say “I'm not paid to do this”. We could argue back, “yes you are, you're getting enhanced preventive fees”' (NHS commissioner, Scotland).

Discussion

The wider and ongoing ENHANCE-D clinical trial presents the potential to substantially change the NHS offer of smoking cessation support in dental settings by informing policy and practice on the effective and cost-effective smoking cessation interventions that can be delivered by DPs. This qualitative evaluation provides insight into stakeholders' perspectives on the facilitators, barriers and strategic changes needed for successful implementation and viability of smoking cessation interventions in primary dental care settings.

Previous studies have surveyed British DPs to explore their attitudes and opinions regarding implementing tobacco cessation strategies in dental practices.10,11Our study is different as we have used interviews rather than questionnaire-style surveys to provide more in-depth and rich data. The earlier studies10,11also explored usual care, which is VBA, designed to be delivered in under 30 seconds. The ENHANCE-D trial is delivering more intensive NRT and EC interventions combined with a single visit behavioural intervention, allowing exploration of the views surrounding these.

NPT was selected as an analytical framework because the study aimed to provide valuable insight on ENHANCE-D intervention acceptability and implementation issues. NPT helps us to understand how practices become embedded and integrated into their social context. This study may have also benefited from using the COM-B model of behaviour13 as a framework to identify what needs to change in order for a behaviour change intervention (ie EC and NRT for smoking cessation) to be effective. The COM-B model identifies three factors that need to be present for any behaviour to occur: motivation, opportunity and capability. This study identified several ‘motivations' for smoking cessation interventions, ‘opportunities'/benefits of smoking cessation interventions in NHS dental practices, and considerations to ensure the ‘capability' of NHS dental practice to implement the interventions as routine practice (see Table 2). However, our focus was on stakeholder perspectives that have the potential to influence adoption of the proposed interventions in NHS primary dental care and therefore, NPT was judged to provide the most appropriate explanatory fit with the data obtained.

This study identified many positive experiences and motivating factors for patients who received the smoking cessation interventions in this trial. However, there were also some perceived barriers that may need to be addressed in a pragmatic sense before considering a wider roll out in primary dental care. As the interventions in this study were part of a funded clinical trial, patients were not required to pay for the intervention (product) they received, and they were additionally incentivised for their participation. This may have motivated some groups of patients to use the interventions provided. Additionally, with the current cost of living pressures, individuals are often looking to identify ways to cut down upon their expenditure. This study found that patients were motivated to substitute cigarette smoking by use of ECs because of their cheaper cost. Patients' views on the cost of ECs relative to a combustible cigarette were consistent with a cross-country survey14 which showed that, although the initial upfront cost of a reusable EC device may be higher than the cost of cigarettes, the average costs of cartridges and e-liquids relative to a pack of cigarettes is lower.14 The ENHANCE-D trial includes an economic evaluation which will explore this in more detail. If smoking cessation interventions in NHS dental practices are rolled out into routine practice in the future, any intervention should entail further education of smokers to correct some misperceptions identified in this study, including that ECs are more dangerous than conventional cigarettes. In 2023, 43% of surveyed UK adults thought that ECs are ‘a lot more', ‘more', or ‘as equally harmful' as cigarettes.15 There should also be tailored recommendations and reassurance strategies for weight management post-smoking cessation for smokers. In this study, some patients believed that stopping smoking leads to unwanted weight gain, and this deterred them from stopping smoking. A narrative review of the literature showed that smoking cessation can cause excessive weight gain in some individuals.16

Administering ECs and NRTs using primary care-based DPs, as exemplified by the ENHANCE-D clinical trial, opens another avenue that would potentially widen the reach of these interventions to smokers, but this would require significant investment. Resources would also be required for appropriate training and reimbursement of DPs, alongside any necessary dental regulatory changes. These are important pragmatic considerations because, similar to the findings of this study, previous research has revealed that DPs often feel inadequately prepared to deliver such smoking cessation advice for a number of reasons previously identified.10,11 However, one of the barriers highlighted by this study (the amount of time needed to complete research-related documentation) would not be needed if these interventions were adopted into mainstream and routine dental practice.

This ENHANCE-D qualitative study has some limitations. We were not able to represent all areas of the UK, or from Wales or Northern Ireland, which operate under different dental regulations. However, participants were recruited from six regions within England and Scotland (Edinburgh hub was excluded as they had no open sites at the time of conducting the qualitative interviews). Only English-speaking patients were interviewed due to resource constraints, and some of those contacted by the research team declined to participate in this qualitative study, without providing a reason. Hence, some patient views could not be captured. Furthermore, we were not able to explore the views of other stakeholders outside of dentistry, including smoking cessation teams, primary care doctors, pharmacists and those working in local authorities who are often involved with delivering smoking cessation activities. There is also the potential that participants may have expressed more positive opinions, particularly towards EC and NRT interventions, because they received the interventions for free as part of this study. Finally, we interviewed participants within a month post-intervention and again six months later. It may have been preferable to have assessed perceptions over a longer duration (eg 12-18 months) to identify potentially changing opinions over time.

The findings from this qualitative study will complement analysis of the main ENHANCE-D clinical findings when they become available. This study will therefore contribute to identifying the perceived value, facilitators, barriers and potential viability of interventions delivered by ENHANCE-D if embedded into primary care dental practice settings more widely. The findings will help to inform policymakers and dental commissioners on the perceived barriers, potential solutions and service-related considerations associated with the interventions used in this study.

Conclusion

Participants were aware of the effects of smoking on oral, general and public health. Patients understood the importance of quitting smoking and responded well to the primary dental care-based smoking cessation interventions. The delivery of smoking cessation interventions by primary dental care teams provides yet another option to ‘make every contact count' and contribute to reducing the burden of cigarette smoking in society. However, to facilitate this, DPs and NHS dental commissioners acknowledge that further training of DPs, changes to NHS dental regulations (including appropriate renumeration), and provision for procurement and storage of pharmacotherapy-related smoking interventions would be required. Further research is needed to explore qualitative findings in the longer-term and at different geographic locations nationally and internationally to build the global body of evidence.

Data availability

Requests to access the data supporting this publication may be made to the corresponding author.

References

Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, Fidler J A, Munafò M. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012; 1248: 107-123.

Bakri N N, Tsakos G, Masood M. Smoking status and oral health-related quality of life among adults in the United Kingdom. Br Dent J 2018; 225: 153-158.

Chambrone L, Preshaw P M, Rosa E F et al. Effects of smoking cessation on the outcomes of non-surgical periodontal therapy: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol 2013; 40: 607-615.

Morris A, Chenery V, Douglas G, Treasure, E. Service considerations - a report from the Adult Dental Health Survey 2009. Available at https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-dental-health-survey/adult-dental-health-survey-2009-summary-report-and-thematic-series (accessed August 2024).

Csikar J, Kang J, Wyborn C, Dyer T A, Marshman Z, Godson J. The Self-Reported Oral Health Status and Dental Attendance of Smokers and Non-Smokers in England. PLos One 2016; 11: e0148700.

UK Government. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 2021. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/delivering-better-oral-health-an-evidence-based-toolkit-for-prevention/chapter-1-introduction#fnref:1 (accessed August 2024).

UK Government. Smokefree and smiling: helping dental patients to quit tobacco. 2013. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/288835/SmokeFree__Smiling_110314_FINALjw.pdf (accessed August 2024).

Holliday R, Hong B, McColl E, Livingstone-Banks J, Preshaw P M. Interventions for tobacco cessation delivered by dental professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021; 2: CD005084.

UK Government. Making Every Contact Count (MECC): Implementation guide. 2018. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/769488/MECC_Implememenation_guide_v2.pdf#:~:text=Making%20Every%20Contact%20Count%20%28MECC%29%20is%20an%20approach,to%20their%20physical%20and%20mental%20health%20and%20wellbeing (accessed August 2024).

Johnson N W, Lowe J C, Warnakulasuriya K A. Tobacco cessation activities of UK dentists in primary care: signs of improvement. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 85-89.

Ahmed Z, Preshaw P M, Bauld L, Holliday R. Dental professionals' opinions and knowledge of smoking cessation and electronic cigarettes: a cross-sectional survey in the north of England. Br Dent J 2018; 225: 947-952.

May C, Finch T. Implementing, Embedding, and Integrating Practices: An Outline of Normalization Process Theory. Sociology 2009; 43: 535-554.

West R, Michie S. A brief introduction to the COM-B Model of behaviour and the PRIME Theory of motivation. Qeios 2020; DOI: 10.32388/WW04E6.

Kai-Wen C, Ce S, Hye Myung L et al. Costs of vaping: evidence from ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. Tob Control 2021; 30: 94-97.

Action on Smoking and Health. Use of e-cigarettes (vapes) among adults in Great Britain. 2023. Available at https://ash.org.uk/uploads/Use-of-e-cigarettes-among-adults-in-Great-Britain-2023.pdf?v=1691058248 (accessed August 2024).

Bush T, Lovejoy J C, Deprey M, Carpenter K M. The effect of tobacco cessation on weight gain, obesity, and diabetes risk. Obesity 2016; 24: 1834-1841.

Murray E, Treweek S, Pope C et al. Normalisation process theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med 2010; 8: 63.

Funding

This study is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) [Health Technology Assessment (NIHR129780)].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Anthony Weke: conceptualisation; investigation; writing - original draft; writing - review & editing. Richard D. Holmes: conceptualisation; investigation; writing - review & editing; supervision. Richard Holliday: conceptualisation; investigator; writing - review & editing; supervision. Elaine McColl: conceptualisation; investigator; writing - review & editing. Chrissie Butcher: conceptualisation; writing - review & editing. Roland Finch: writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

This qualitative study is a component of the wider ENHANCE-D clinical trial [project reference number: NIHR129780]. The trial is registered with the following references: IRAS 1004761; EudraCT 2021-005440-30; NHS REC 22/NE/0040; ISRCTN 13158982. A participation information sheet was issued to all potential participants and written informed consent was obtained for all participants in line with the study's ethical approval.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.© The Author(s) 2024.

About this article

Cite this article

Weke, A., Holmes, R., McColl, E. et al. Delivering smoking cessation interventions in NHS primary dental care - lessons from the ENHANCE-D trial. Br Dent J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7850-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7850-5

This article is cited by

-

‘I am enthusiastic about the future of my career'

BDJ Team (2025)