Abstract

Aim The study aims to conduct economic evaluation of the Peninsula Dental Social Enterprise (PDSE) programme for people experiencing homelessness over an 18-month period, when compared to a hypothetical base-case scenario (‘status quo').

Methods A decision tree model was generated in TreeAge Pro Healthcare 2024. Benefit-cost analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis were performed using data informed by the literature and probabilistic sensitivity analysis (Monte Carlo simulation with 1,000 cycles). The pre-determined willingness-to-pay threshold was estimated to be £59,502 per disability-adjusted life year (DALY) averted. Costs (£) and benefits were valued in 2020 prices. Health benefits in DALYs included dental treatment for dental caries, periodontitis and severe tooth loss.

Results The hypothetical cohort of 89 patients costs £11,502 (SD: 488) and £57,118 (SD: 2,784) for the base-scenario and the PDSE programme, respectively. The health outcomes generated 0.9 (SD: 0.2) DALYs averted for the base-case scenario, and 5.4 (SD: 0.9) DALYs averted for the PDSE programme. The DALYs averted generated £26,648 (SD: 4,805) and £163,910 (SD: 28,542) in benefits for the base-scenario and the PDSE programme, respectively. The calculated incremental benefit-cost ratio was 3.02 (SD: 0.5) and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was £10,472 (SD: 2,073) per DALY averted. Uncertainty analysis demonstrated that the PDSE programme was 100% cost-effective.

Conclusions Funding a targeted dental programme from the UK healthcare perspective that provides timely and affordable access to dental services for people experiencing homelessness is cost-effective.

Key points

-

The community-based, targeted, Peninsula Dental Social Enterprise programme is a cost-effective model for delivering care to people experiencing homelessness.

-

Governments should consider the broader benefits and health impacts when providing dental services to vulnerable populations.

-

Policy decision-makers should look beyond cost-efficiency comparisons when formulating dental funding arrangements and related resource allocation decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oral health is an integral part of overall health and plays an important role in the wellbeing of individuals and populations.1 The majority of oral diseases can be prevented. Yet, they remain a global public health challenge, affecting more than 3.5 billion people worldwide.2 Socially excluded and vulnerable groups in society are disproportionately affected, with people in each lower socioeconomic position category exhibiting successively worse oral health.3 The effects of oral diseases in terms of quality of life and economic impact are significant,4 contributing to 5-10% of health expenditure (>£3 billion/year).

Homeless populations experience the ‘cliff-edge' of inequities as they experience very high levels of oral disease, including dental caries, periodontal disease and tooth loss, as well as increased risk of oral cancer.5,6,7,8 Additionally, there are often significant challenges in accessing dental services compared to the general population,9 commonly resulting in late presentation of oral diseases and the use of emergency department visits.10 It has been estimated that the health and social care needs of people experiencing severe and multiple disadvantage (which includes a combination of homelessness, problematic substance use and repeat offending) cost the UK public sector around £10 billion/year.11

In the UK, access to NHS dentistry has become increasingly challenging for all population groups. However, vulnerable people encounter additional barriers in accessing timely care.8 Both the lived experience of homelessness and feature characteristics of dental services act as barriers to oral health.9 There are variations in the utilisation of dental services among the UK population,12 which suggest that different models of care are required for different population groups.

Considering that many people experiencing homelessness find it challenging to access dental services, the Smile4life survey indicated a clear need for alternative models of care that supports people experiencing homelessness.13 This should include three ‘tiers' of dental care: 1 = emergency dental services for those unable to access routine dental care; 2 = single-item treatments provided on an ad hoc occasional basis without the need to attend a full course of treatment; and 3 = routine dental care/full course of treatment.13 Taking into account the ‘unfair and avoidable differences in health across the population and between different groups in society',14 the NHS long term plan highlights the important role that social enterprises can play in improving health outcomes.15 This is due to their advantage in being able to respond more flexibly to patient needs than other NHS bodies.

Responding to local needs, Peninsula Dental Social Enterprise (PDSE), the clinical provider of the Dental School at the University of Plymouth in the South West of England, developed a community model of delivering dental care for people experiencing homelessness (details of the PDSE programme have been described elsewhere).16 The service provides routine and urgent care by a qualified dentist. An evaluation of the service highlighted significant patient benefits which often acted as a catalyst for change in multiple areas of a patient's life.16

In fiscal terms, the analysis showed a significant gap between government funding levels and the actual cost of treating this population group,16 meaning that a service contract based on NHS England's current funding structure would not be economically viable. However, the degree to which the PDSE programme is cost-effective has not been investigated. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has guidelines that use economic evaluation to inform resource allocation decisions,17 and which consider both costs and health outcomes. An economic evaluation of the PDSE programme can provide important insight relevant to the future commissioning of services for groups experiencing social exclusion.

Aim

The aim of this study was to conduct economic evaluation of the PDSE programme for people experiencing homelessness when compared to a hypothetical scenario of ‘status quo'.

Methodology

Economic evaluation was conducted to determine whether the PDSE programme is a cost-effective intervention from the UK healthcare perspective. The PDSE population cohort included 89 patients experiencing homelessness who accessed dental services within a period of approximately 18 months.

This study was conducted using publicly available data in the literature and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Therefore, this economic evaluation study is exempt from requiring ethics approval. All data used for the PDSE programme were previously published and received ethics approval approved by the Faculty of Health Research Ethics and Integrity Committee, University of Plymouth (ID 17/18-854).16 Therefore, this economic evaluation study, including additional patient consent from the PDSE programme, is exempt from requiring further ethics approval.

Base-case scenario (‘status quo')

A hypothetical cohort of patients experiencing homelessness was created as the base-case scenario. It assumed that only 17% of them had used dental services in the last 1-2 years.18 Timely access would have prevented disability. In addition, 27% of patients in this cohort would have at least one accident and emergency (A&E) admission due to dental problems,18 likely due to worsened severity of dental caries. Given that there was an absence of A&E re-admissions, it was assumed that this rate was 3.244 over 18 months.19 For patients who did not use dental services, they had 1.32 higher odds for A&E admission.20

Peninsula Dental Social Enterprise (intervention)

The intervention included all 89 patients experiencing homelessness who accessed dental services offered by PDSE. Treatments that were provided included 298 extractions, 224 restorations, three root canal treatments, 29 periodontal treatments, 38 partial dentures and 28 full dentures.16

Modelling approach

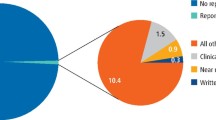

Benefit-cost analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis were conducted using the decision tree method using Treeage Pro Healthcare 2024 (TreeAge Software, LLC), with probabilistic sensitivity analysis using Monte Carlo simulation with 1,000 cycles (Fig. 1). Where appropriate, cost parameters were generated using the gamma distribution with ±10% of the expected value being assigned as the 95% confidence interval. The same rationale was applied to outcome parameters using normal distributions. A summary of the parameter variables is reported in Table 1.

The decision tree model developed for economic evaluation of the PDSE programme. (Probability_Access_Dentistry = proportion of people experiencing homelessness accessing dental services [last 1-2 years]; Probability_A_E_Homeless = proportion of people experiencing homelessness having an admission and emergency visit; NHS_Dentistry_Refusal_Odds = increased odds of an admission and emergency visit if access to NHS dentistry was refused)

Time horizon

The selected time horizon is 18 months.

Health benefit modelling

Estimating disability-adjusted life years

Health outcomes were quantified using methods adapted from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study22 to derive disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) averted. The health benefits included dental treatment for dental caries, periodontitis and severe tooth loss.

The disability weight of 0.010 (SD: 0.004) for dental caries22 was applied to extractions, root canal treatment and restorations. Time spent with disability includes two components: 1) terminal pain; and 2) periodic pain. Terminal pain was relevant to extraction and root canal treatment, which assumed constant pain for 55.2 days.23 Periodic pain was applied for restorative procedures, which is a disability equivalent to one hour per day for the same duration of terminal pain.

For patients who received periodontal treatment, the disability weight of 0.007 (SD: 0.003) for periodontitis22 was applied, with DALYs averted for one year.

Similarly, prosthetic dental services provided for partial and full dentures were associated with DALYs averted due to severe tooth loss. The disability weight of 0.067 (SD: 0.013) for severe tooth loss22 was applied for the 18-month period.

For patients who had an A&E admission, it was assumed that DALYs accrued due to symptomatic utilisation of healthcare, primarily due to dental caries, was the common cause of dental pain.24,25

Costs

Costs are reported in the national currency (£) in 2020 prices.

For the intervention, each patient received dental services that had an average health expenditure of £854.50.16

The healthcare costs of an A&E admission is estimated to be £344, calculated from £418 in 202421 deflated to 2020 prices.26

Discount rate

Given the short time horizon of 18 months, neither costs nor outcomes were discounted.

Economic evaluation

Economic evaluation is the comparative analysis of an alternative care pathway in terms of both costs and outcomes.27

For the benefit-cost analysis, the incremental benefit-cost ratio (IBCR) was calculated to determine the marginal benefit in monetary terms relative to the costs of the intervention being compared. DALYs can be converted into monetary value based on previous costing methods.28 One DALY is equal to £30,504 gross domestic product per capita in 2020 constant prices.29 If an intervention resulted in DALYs averted, it is considered a benefit, and vice versa; DALYs accrued is treated as a cost.30 An IBCR greater than one indicates there is more benefit in monetary terms relative to the costs. The IBCR is calculated using the formula:

where the benefit includes DALYs averted converted into costs, and the costs include both the cost of the care pathway and the DALYs accrued converted into costs.

With the cost-effectiveness analysis, the calculated incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was compared to a pre-determined willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold. The WTP is a concept whereby a specified ‘threshold' of monetary value is assigned to each unit of outcome gained to determine whether an intervention is cost-effective, usually decided by the decision-maker. In principle, if the additional cost generated by an additional unit of outcome is below the WTP threshold, the alternative care pathway should be adopted. Given that the NICE guideline does not have a WTP threshold per DALY averted, this was estimated as £59,502 per DALY averted, with the UK considered a very high-income country (US $69,499 in 2016 inflated to 2020 prices and converted to £.31 The ICER is calculated using the formula:

where the outcome is DALYs accrued, and the cost component includes the costs of the care pathways.

Results

The economic evaluation modelled results are reported in Table 2.

The total estimated costs were £57,118 (SD: 2,784) for the PDSE programme and £11,502 (SD: 488) for the base-case scenario. The PDSE programme generated 5.4 (SD: 0.9) DALYs compared to 0.9 (SD: 0.2) DALYs averted for the base-case scenario. When DALYs were converted into monetary value, the benefits were £163,910 (SD: 28,542) for the PDSE programme and £26,648 (SD: 4,805) for the base-case scenario.

The IBCR was calculated to be 3.02 (SD: 0.5) ie for every pound invested into the PDSE programme, the intervention produced an additional benefit of £2.02. The ICER was calculated to be £10,472 (SD: 2,073) per DALY averted. The cost-effectiveness plane (Fig. 2) shows that the PDSE programme is 100% cost-effective and was robust to probabilistic sensitivity analysis. Each green dot indicates modelled outputs being cost-effective when comparted against the WTP threshold of £59,502 per DALY averted. The green circle indicates the 95% confidence interval of the 1,000 modelled data points.

Discussion

Our study has shown that the PDSE programme for people experiencing homelessness is a cost-effective intervention with significant health benefits in terms of DALYs averted. Considering the high rate of visits to A&E for dental problems by people who experience homelessness, and associated cost implications, our findings have significant implications for the commissioning of dental services from the NHS. To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the cost-effectiveness of a dedicated model that provides urgent and routine dental care for people experiencing homelessness.

It is very common for people experiencing homelessness to suffer from the most severe complications of oral diseases, such as pain and infections, and for these to go untreated or to require emergency care.2,5,10 A study in the USA10 has shown that odontogenic infections causing pain accounted for over 80% of emergency department visits for this population. Also, 46% of people experiencing homelessness who visited the emergency department for dental problems did so more than once during the study period.10 As the authors suggest,10 repeat emergency department visits indicate that dental problems impacted significantly on people experiencing homeless, and that they were unable to access appropriate dental care in the community. The treatment of non-traumatic dental problems at the emergency department is particularly interesting, since most of these problems can be resolved more effectively in a dental surgery.10 Insufficient access to dental care has been confirmed by both national and international studies, which indicate that this population has very limited access to routine and preventive healthcare.32,33

The Marmot review highlighted how the most advantaged groups often stand to get the greatest benefit from population-wide interventions.34 Therefore, without attention to distributional impact, such interventions may actually increase inequities.34 If the steepness of the social gradient in health is to be decreased, it is essential that we act universally, but at a scale and intensity proportional to the level of disadvantage and of health needs.34 The unequal distribution and burden of oral diseases among vulnerable groups, including people experiencing homelessness, necessitates the development of novel dental care pathways which allow dental professionals to respond flexibly to the complex needs of this group.

In contrast to traditional models of NHS dentistry, where some patients may be required to pay for a proportion of treatment costs, the PDSE community clinic is free of charge to patients and provides flexibility around attendance. Despite an earlier evaluation demonstrating that the average cost per treatment course compares unfavourably with NHS contract funding if the service were solely state funded,16 the current study identified an additional £2.02 in cost benefits for every pound invested in the PDSE programme. This can be explained by the health benefits gained in monetary value and the ability to access timely routine and urgent care through a supportive community model.

Besides the oral health improvements of people receiving dental care through the PDSE programme, there can be additional productivity and financial benefits to the NHS funding pool because of freed-up capacity in other parts of the NHS system. The transfer of dental commissioning responsibilities of dental services to integrated care boards may present new opportunities for innovative commissioning of place-based models that tailor care to the needs of targeted populations. Further investigation of such data could be undertaken in studies.

There are currently different service models that provide dental care to people experiencing homelessness in England. Examples of best practice targeted services include ‘primary care delivery (“high street” dental practices), mobile dental units (MDUs) and community clinics operated through social enterprises'.35 Since people experiencing homelessness have diverse needs, these models can complement each other to ensure that patients have access to dental care that is tailored to their circumstances.35 Although a cost analysis of high street practices and MDUs is yet to be conducted, MDUs have shown to increase costs, with units of dental activity (UDAs) at MDUs costing 2.4 times more than UDAs at fixed sites.36 For some people experiencing homelessness, an MDU might be more effective, so a more costly model such as this may be justified according to local conditions.37 Further research is warranted into the cost-effectiveness of different targeted models when compared to mainstream ones.

Healthcare provision must be rationally targeted to those at greatest risk, in the greatest need and experiencing the greatest difficulty accessing treatment, with care tailored effectively to their individual situations.36 Considering high levels of co-morbidity among people experiencing homelessness and their complex social care needs, integrating health and social care appears to be an effective way of organising care around the individual. Some suggested ways to achieve this include co-location with other health or food provision facilities, or in open-access day centres with housing and social services, establishing links with support organisations and offering cross-referral opportunities between services.37

The integration of health and social care can improve overall wellbeing outcomes for people experiencing homelessness, as well as contributing to ending homelessness,38 with potential economic and societal benefits. The need for a combination of downstream, midstream and upstream interventions to promote oral health equity across the population39 should not be underestimated. Additionally, to tackle oral diseases, it is necessary to have, across the healthcare system, a focus on prevention that considers service delivery models that are tailored to and meet the needs of the target population.

Strengths and limitations

A main strength of this study is that it expands on the application of economic evaluation techniques less commonly used in oral health contexts, such as periodontitis40 and severe tooth loss. Furthermore, modelled economic evaluations in oral health have often used a tooth-level model rather than the person-level model approach used in this study. Our work also synthesised and applied a methodology that combined the cumulative health outcomes in DALYs across three common oral diseases as a more realistic care pathway, instead of an intervention targeting one oral disease at a time as mutually exclusive health states.

It is common that studies conducting the economic evaluation of oral health interventions use outcome measures that make it impossible to determine whether an intervention is cost-effective due to the absence of WTP thresholds,40 other than those established for DALYs and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). The NICE guidelines generally adopt an explicit threshold of £20,000-£30,000 per QALY gained.17 Furthermore, our study provides a fairly conservative estimate of the DALYs averted generated from the PDSE programme, given that many people experiencing homelessness do not have regular access to affordable dental care, and 13% had not seen a dental practitioner for more than ten years.18

A key limitation of this study is the biased assignment of a hypothetical cohort of patients for the base-case scenario as the comparator to the PDSE programme. Ideally, matched data on A&E admissions, dental service utilisation and health outcomes at an individual level should be used for economic evaluation for both cohorts of people experiencing homelessness. However, it would be ethically problematic to deny dental care to patients if they are assigned to the base-case scenario under a more robust study design, like a randomised controlled trial, given the high needs of people experiencing homelessness.16,18

There are some limitations to the analysis which relate to the specific service model delivered by the PDSE programme and its costs, which includes provision for additional administration and outreach activities not associated with the delivery of dental services to people experiencing homelessness in other NHS settings. However, despite these additional costs, the PDSE programme was still found to be cost-effective. Previous research has shown that community-based targeted dental programmes can potentially reduce homelessness and improve employability,41 and increasing dental care access can reduce dental-related emergency department visits.42 Whether the PDSE programme has led to a reduction in unscheduled dental care appointments or attendances at A&E is currently unknown.

Conclusions

Dental care provision for people experiencing homelessness necessitates using various service models that take their unique circumstances into consideration. Our study has shown that despite the higher cost compared to the standard NHS contract funding model, a community-based targeted service is a cost-effective model for delivering timely and affordable care to people experiencing homelessness. NHS dental commissioning approaches must shift from focusing on costs based on UDAs to one that focuses on need and reducing inequities in access to dental care.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Peres M A, Macpherson L M D, Weyant R J et al. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet 2019; 394: 249-260.

Watt R G, Daly B, Allison P et al. Ending the neglect of global oral health: time for radical action. Lancet 2019; 394: 261-272.

Sabbah W, Tsakos G, Chandola T, Sheiham A, Watt R G. Social gradients in oral and general health. J Dent Res 2007; 86: 992-996.

Jevdjevic M, Trescher A-L, Rovers M, Listl S. The caries-related cost and effects of a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages. Public Health 2019; 169: 125-132.

McGowan L J, Joyes E C, Adams E A et al. Investigating the Effectiveness and Acceptability of Oral Health and Related Health Behaviour Interventions in Adults with Severe and Multiple Disadvantage: Protocol for a Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 11554.

UK Government. Inequalities in oral health in England. 2021. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6051f994d3bf7f0453f7b9a9/Inequalities_in_oral_health_in_England.pdf (accessed March 2024).

Stennett M, Tsakos G. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on oral health inequalities and access to oral healthcare in England. Br Dent J 2022; 232: 109-114.

Watt R G, Venturelli R, Daly B. Understanding and tackling oral health inequalities in vulnerable adult populations: from the margins to the mainstream. Br Dent J 2019; 227: 49-54.

Paisi M, Kay E, Plessas A et al. Barriers and enablers to accessing dental services for people experiencing homelessness: a systematic review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2019; 47: 103-111.

Figueiredo R, Dempster L, Quiñonez C, Hwang S W. Emergency Department Use for Dental Problems among Homeless Individuals: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2016; 27: 860-868.

Lankelly Chase Foundation. Hard edges: mapping severe and multiple disadvantage in England. 2015. Available at https://lankellychase.org.uk/publication/hard-edges/ (accessed March 2024).

O'Connor R, Landes D, Harris R. Trends and inequalities in realised access to NHS primary care dental services in England before, during and throughout recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Br Dent J 2023; DOI: 10.1038/s41415-023-6032-1.

Coles E, Edwards M, Elliott G M, Freeman R, Heffernan A, Moore A. Smile4life: The oral health of homeless people across Scotland. 2009. Available at https://discovery.dundee.ac.uk/files/3399534/smile4life_report.pdf (accessed March 2024).

NHS England. What are healthcare inequalities? Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/what-are-healthcare-inequalities/ (accessed March 2024).

NHS. NHS Long Term Plan. 2019. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf (accessed March 2024).

Paisi M, Baines R, Worle C, Withers L, Witton R. Evaluation of a community dental clinic providing care to people experiencing homelessness: a mixed methods approach. Health Expect 2020; 23: 1289-1299.

Sculpher M, Palmer S. After 20 Years of Using Economic Evaluation, Should NICE be Considered a Methods Innovator? Pharmacoeconomics 2020; 38: 247-257.

Groundswell. Healthy Mouths: A peer-led health audit on the oral health of people experiencing homelessness. Available at https://tfl.ams3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/media/documents/Groundswell-Healthy-Mouths-Report-Final-Web-2_sic5EBa.pdf (accessed February 2024).

Lewer D, Menezes D, Cornes M et al. Hospital readmission among people experiencing homelessness in England: a cohort study of 2772 matched homeless and housed inpatients. J Epidemiol Community Health 2021; 75: 681-688.

Elwell-Sutton T, Fok J, Albanese F, Mathie H, Holland R. Factors associated with access to care and healthcare utilization in the homeless population of England. J Public Health 2017; 39: 26-33.

The Kings Fund. Key facts and figure about the NHS. Available at https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/data-and-charts/key-facts-figures-nhs (accessed February 2024).

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020; 396: 1204-1222.

Whyman R A, Treasure E T, Ayers K M. Dental disease levels and reasons for emergency clinic attendance in patients seeking relief of pain in Auckland. N Z Dent J 1996; 92: 114-117.

Boeira G F, Correa M B, Peres K G et al. Caries is the main cause for dental pain in childhood: findings from a birth cohort. Caries Res 2012; 46: 488-495.

Pentapati K C, Yeturu S K, Siddiq H. Global and regional estimates of dental pain among children and adolescents—systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2021; 22: 1-12.

Bank of England. Inflation calculator. Available at https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator (accessed February 2024).

Drummond M F, Sculpher M J, Claxton K, Stoddart G L, Torrance G W. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Righolt A J, Jevdjevic M, Marcenes W, Listl S. Global-, Regional-, and Country-Level Economic Impacts of Dental Diseases in 2015. J Dent Res 2018; 97: 501-507.

International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook Database April 2022 Edition. Available at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2022/April (accessed November 2023).

Woldemariam W. Prioritization of Low-Volume Road Projects Considering Project Cost and Network Accessibility: An Incremental Benefit-Cost Analysis Framework. Sustainability 2021; 13: 13434.

US Inflation Calculator. Available at https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/ (accessed December 2023).

Daly B, Newton T J, Batchelor P. Patterns of dental service use among homeless people using a targeted service. J Public Health Dent 2010; 70: 45-51.

Freitas D J, Kaplan L M, Tieu L, Ponath C, Guzman D, Kushel M. Oral health and access to dental care among older homeless adults: results from the HOPE HOME study. J Public Health Dent 2019; 79: 3-9.

Institute of Health Equity. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: The Marmot Review. 2010. Available at www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-full-report-pdf.pdf (accessed July 2022).

Serban S, Bradley N, Atkins B, Whiston S, Witton R. Best practice models for dental care delivery for people experiencing homelessness. Br Dent J 2023; 235: 933-937.

Simons D, Pearson N, Movasaghi Z. Developing dental services for homeless people in East London. Br Dent J 2012; DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.891.

Bradley N, Heidari E, Andreasson S, Newton T. Models of dental care for people experiencing homelessness in the UK. a scoping review of the literature. Br Dent J 2023; 234: 816-824.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Integrated health and social care for people experiencing homelessness. 2022. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng214/resources/integrated-health-and-social-care-for-people-experiencing-homelessness-pdf-66143775200965 (accessed March 2024).

Dawson E R, Stennett M, Daly B, Macpherson L M D, Cannon P, Watt R G. Upstream interventions to promote oral health and reduce socioeconomic oral health inequalities: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2022; DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059441.

Nguyen T M, Tonmukayakul U, Le L K, Calache H, Mihalopoulos C. Economic Evaluations of Preventive Interventions for Dental Caries and Periodontitis: A Systematic Review. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2023; 21: 53-70.

Ghoneim A, Ebnahmady A, D'Souza V et al. The impact of dental care programs on healthcare system and societal outcomes: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2022; 22: 1574.

Cothron A, Diep V K, Shah S et al. A systematic review of dental-related emergency department visits among Medicaid beneficiaries. J Public Health Dent 2021; 81: 280-289.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organised by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: Tan Minh Nguyen, Robert Witton, Martha Paisi; investigation: Tan Minh Nguyen; formal analysis: Tan Minh Nguyen; investigation: Robert Witton, Lyndsey Withers, Martha Paisi; methodology: Tan Minh Nguyen, drafting the article: Tan Minh Nguyen; validation: Tan Minh Nguyen, Robert Witton, Lyndsey Withers, Martha Paisi; writing - original draft: Tan Minh Nguyen, Martha Paisi; writing - review and editing: Tan Minh Nguyen, Robert Witton, Lyndsey Withers, Martha Paisi.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This study was conducted using publicly available data in the literature and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Therefore, this economic evaluation study is exempt from requiring ethics approval. All data used for the PDSE programme were previously published and received ethics approval approved by the Faculty of Health Research Ethics and Integrity Committee, University of Plymouth (ID 17/18-854).16 Therefore, this economic evaluation study, including additional patient consent from the PDSE programme, is exempt from requiring further ethics approval.

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.© The Author(s) 2024.

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, T., Witton, R., Withers, L. et al. Economic evaluation of a community dental care model for people experiencing homelessness. Br Dent J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-8166-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-8166-1