Abstract

Background

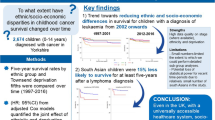

Previous social determinants of health (SDoH) studies on laryngeal cancer (LC) have assessed individual factors of socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity but seldom investigate a wider breadth of SDoH-factors for their effects in the real-world. This study aims to delineate how a wider array of SDoH-vulnerabilities interactively associates with LC-disparities.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study assessed 74,495 LC-patients between 1975 and 2017 from the Surveillance-Epidemiology-End Results (SEER) database using the Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) from the CDC, total SDoH-vulnerability from 15 SDoH variables across specific vulnerabilities of socioeconomic status, minority-language status, household composition, and infrastructure/housing and transportation, which were measured across US counties. Univariate linear and logistic regressions were performed on length of care/follow-up and survival, staging, and treatment across SVI scores.

Results

Survival time dropped significantly by 34.37% (from 72.83 to 47.80 months), and surveillance time decreased by 28.09% (from 80.99 to 58.24 months) with increasing overall social vulnerability, alongside advanced staging (OR 1.15; 95%CI 1.13–1.16), increased chemotherapy (OR 1.13; 95%CI 1.11–1.14), decreased surgical resection (OR 0.91; 95%CI 0.90–0.92), and decreased radiotherapy (OR 0.97; 95%CI 0.96–0.99).

Discussion

In this SDoH-study of LCs, detrimental care and prognostic trends were observed with increasing overall SDoH-vulnerability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Laryngeal cancer accounted for nearly 19% of all new head and neck cancer diagnoses in the United States in 2023 [1]. While the incidence of laryngeal cancer has decreased over the past 30 years, overall mortality rates have increased, largely contributed by patients being diagnosed with late-staged malignancies on first presentation [2]. Thus, many investigations have sought to identify what clinicodemographic factors have contributed to this increased risk for morbidity and mortality related to laryngeal cancer.

Social determinants of health (SDoH) have been increasingly investigated in relation to the disparities found within head and neck cancers (HNC) in adult populations. Studies have found that patient race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), sex, insurance status, and rurality, each account for disparities in survival of HNC [3,4,5]. Regarding laryngeal cancer, Liu et al. [6] observed that patients with higher SES had better survival, but Black patients with high SES had significantly decreased survival rates compared to White patients. Shaikh et al. [7] found that being a member of a racial or ethnic minority, advanced age, female sex, residing more than 30 miles from treatment a facility, and lack of insurance, was associated with greater diagnosis-to-treatment interval. However, given that the influences of SDoH are simultaneously experienced and derived from a patient’s lived-in environment, prior investigations have yet to encapsulate this amalgamated impact of these represented factors and others, downplaying the actual apparent disparities imparted by SDoH, especially in regards to SDoH-vulnerabilities on a community-level. Thus, comprehensive approaches to assess this interplay of a larger scope of SDoH and their associations with disparities in laryngeal cancer remains in dire need.

The Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) is a tool developed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention based on US Census data featuring 15 SDoH factors grouped into 4 themes: SES, household composition, minority race/ethnicity and English language status, and housing type & transportation [8]. These themes are ranked along every census tract and county, creating a nation-wide framework by which clinicians can quantifiably evaluate social vulnerability influence and their relation to health disparities. The SVI has been utilized previously to evaluate the interaction between multiple SDoH and their impact on care and survival in pediatric HNC and head and neck melanomas [9, 10]. Given the gaps in understanding SDoH-influences on laryngeal cancer disparities, our study aims to apply SVI towards a national patient cohort to analyze the relationships of summated and specific SDoH-vulnerabilities with the care and prognostic outcomes of adult laryngeal squamous cell cancer patients in the United States.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. The Northwestern University IRB/ethics committee has exempted this study (STU00216871) due to the data queried consisting of publicly available, de-identified data.

Databases

The CDC-SVI was queried for ranked scores among 15 census factors within four SDoH themes of socioeconomic status (poverty, unemployment, income level, high school, diploma status), minority status-language (minority status, proficiency with English), household composition (household members 65+ years, household members ≤ 17 years, disability status, single-parent status), and housing-transportation (multiunit structure, mobile homes, crowding, no vehicle, group quarters), as well as total composite scores. Based on CDC-SVI documentation, SVI-theme sub-scores are differentially weighed to formulate the total composite score and are assigned different weights based on sociodemographic-census data of the designated area. Total and SVI-theme scores are based on relative social vulnerabilities of a particular census tract among all 72,158 US census tracts, ranging from 0 to 1, with 0 representing the lowest social vulnerability and 1 representing the highest [8]. Further description of these formulations can be found in the Methods Supplement.

The National Cancer Institute-Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (NCI-SEER) database contains national datasets of patient variables, pathological characteristics, treat- ment modalities, and prognostic outcomes. Months under surveillance represent a length-of-care measurement reflecting the active follow-up a patient receives for their primary malignancy up until the last provider interaction. Months survival represents active follow-up until patient suffers a mortal outcome.

SVI scores were abstracted and matched to SEER-patient data based on county of residence at the time of diagnosis. County-assigned scores were generated by weighted score means per population density of each census tract within the county. These methodologies were adapted from prior SVI-based investigations for heterogenous database linkage [9, 10]. A schematic workflow of this data linkage process can be found in Supplement eFigure 1. These are also fully described in the Methods Supplement.

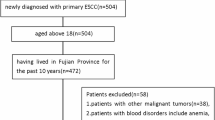

Population definitions

SEER was queried for adult (20+ years) patients diagnosed with laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas between 1975 and 2017. Head–neck regions were extracted using International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3) topographic codes [C32.0-C32.9].

Statistical analysis

Months surveillance or followed up within each disease class were analyzed by total CDC-SVI score and theme subscores. CDC-SVI scores were split into relative equivalently sampled quintiles based on actual scores within each disease class. The relative SVI quintiles were delineated by quintiles of gradually increasing percentile based on their actual SVI-scores (i.e. “less than 20’, “20 to 39.99”, “40 to 59.99”, “60 to 79.99”, and “80 to 99.99”) per disease class (e.g., within disease A, patients with the lowest CDC-SVI scores are grouped into the “less than 20” quintile group, then the “20 to 39.99” represents the next set of higher scores, and etc.).

Among these total and SVI-theme quintiles, differences between the mean surveillance months for lowest and highest SVI- scored quintiles were calculated. Trend significance was assessed by linear regression across all data points against relative-SVI quintiles for surveillance months (i.e., not a trend through the base- line descriptive values), and violin plots were generated to assess relative sample distribution for surveillance months along the contour widths within each relative-SVI quintile while simultaneously measuring the median, interquartile range (IQR), and 1.5 times the IQR with its inner box plot. Means, standard deviations, and ranges for surveillance months per quintile were also calculated. The proportion of patients who were alive/lost to follow-up or dead was calculated per quintile.

Survival months were analyzed similarly as surveillance months. However, patients who were alive/lost upon last follow-up were excluded to extract patients who were dead upon last follow-up. Primary surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation (external beam) therapy occurrence and advanced staging on time of diagnosis within disease classes were analyzed with univariate logistic regression across relative SVI quintiles per CDC-SVI category (reference being least socially vulnerable/”<20” quintile, compared to increasing quintiles of vulnerability). Univariate analyses, rather than multivariate, were selected due to the preservation of differential weights applied to each of the SVI-themes in formulating the total/overall SVI scores for each region. Full description of this rationale.

Statistical significance was set as p-value < 0.05. Two-sided p-values were reported for analyses.

Results

There were 74,495 patients with laryngeal squamous cell neoplasms identified in the SEER database and included in the analytic cohort. The most represented clinicodemographic characteristics were patients aged 65–84 years (n = 34,651, 46.5%), being of male sex (n = 60,114, 80.7%), non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity (n = 56,606, 76.0%). Primary sites of glottic (n = 39,779, 53.4%), supraglottic (n = 25,672, 34.5%), and subglottic (n = 1129, 1.5%) were well-represented. Total SVI scores ranged from 0.000 to 0.947. SES SVI scores ranged from 0.000 to 0.976. Minority-language (ML) SVI scores ranged from 0.002 to 0.945. Household-composition (HC) SVI scores ranged from 0.091 to 0.971. Housing-transportation (HT) SVI scores ranged from 0.051 to 0.942.

Further patient clinical characteristics stratified by total CDC-SVI scores are summarized in Table 1.

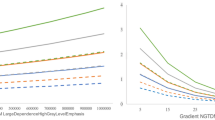

Trends in survival months with increasing social vulnerability

With increased total SVI score, significant decreases in mean months survival among patients with laryngeal cancer were observed. Significant differences in mean months survival between the lowest and highest total SVI quintile was 34.37% (72.83 to 47.80 months; p < 0.001) (Fig. 1, Supplement eFigure 2). By magnitude, SES vulnerabilities were the greatest contributors to total vulnerability trends, followed by HC, HT, then ML status (Fig. 1).

Trends in months under surveillance with increasing social vulnerability

Mirroring the trends seen in survival, there was a significant decrease in months of surveillance/follow-up with increasing total SVI score. Between the first and fifth SVI quintile, surveillance time decreased 28.09% (80.99 to 58.24 months; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2, Supplement eFigure 3. Across SVI trends, SES vulnerabilities contributed the most to total vulnerability trends, followed by HC and HT (Fig. 2).

Advanced staging and high grading on presentation occurrence with increasing social vulnerability

Increasing total SVI score was associated with increased odds of advanced staging (OR 1.15; 95% CI, 1.13–1.16, p < 0.001) and high grading (OR 1.02. 95%CI 1.01–1.03; p = 0.029). For advanced staging, SES-vulnerability was most associated with this overall trend, followed by HC and HT. For high grade, HT was most associated with this overall trend (Table 2).

Treatment receipt with increasing social vulnerability

Patients with laryngeal cancers displayed significantly increased odds of receiving chemotherapy with increased total SVI score (OR 1.13; 95% CI, 1.11–1.14; p < 0.001). Increasing SES, followed by HC-vulnerability contributed to these overall social vulnerability trends of chemotherapy receipt (Table 3).

Increases in total social vulnerability were associated with significantly decreased odds of a patient receiving radiation therapy (OR 0.97; 95% CI, 0.96–0.99; p < 0.001). SES vulnerability contributed significantly to these overall social vulnerability trends (Table 3).

Increasing total SVI scores were associated with significantly decreased odds of having surgical resection performed (OR 0.91; 95% CI, 0.90–0.92; p < 0.001). SES vulnerability contributed significantly to these overall social vulnerability trends (Table 3).

Discussion

To our current knowledge, this is the first study to utilize the SVI comprehensively in order to evaluate the impact of SDoH in a nationally-representative patient population diagnosed with laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas while accounting for the differential influence of multiple social vulnerability factors. Overall, increasing social vulnerability were associated with decreases in months under surveillance and survival, increased odds of advanced staging at presentation, and decreased odds of radiation therapy or primary surgery receipt.

As demonstrated by our group’s prior work, the SVI themes offer a distinctive interpretation of the interplay between SDoH factors, influencing the associations between social vulnerability and laryngeal cancer outcomes [9, 10]. These methods allow for showcasing how the culmination of multiple social vulnerabilities impact patient outcomes while simultaneously elaborating on the interactions of each SDoH theme on one another. Instead of utilizing individual-level variables of SDoH, the SVI factors in the sociodemographic contexts of each census tract by differentially weighing each theme sub-score to calculate total social vulnerability. This adaptable feature of the SVI allowed for our utilization of non-multivariable regression analyses, as performing such multivariate analyses would result in many of the SVI associations and their outcomes without their sociodemographic contexts properly represented. Even in comparison to other large data SDoH-indices, such as the Yost Index or Area Deprivation Index, the SVI’s features in delineating separate themes of varied SDoH-factors remain unique [11,12,13].

The results of our study align with many of those that examined the impact of singular social vulnerabilities on patients with laryngeal cancer. For instance, previous findings that members of racial and ethnic minority groups present with further advanced stages of disease, experience differences in treatment modalities as compared to white patients, and have decreased overall survival conferred with our own [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. However, our study did contrast previous findings with regard to minority group status and its association with advanced initial disease staging [22,23,24]. Specifically, Shin et al. [22] observed that black and Hispanic patients in the SEER database were diagnosed with advanced stage disease significantly more often than white patients were. Our group found that the ML sub-group was the only theme not associated with increased odds of advanced staging at presentation. This poses the question of whether the advanced staging of disease attributed to race was not due to confounding SDoH variables. Nevertheless, while previous studies explain the individual impact of minority status, ours demonstrates that its impact across various clinical outcomes is still significant in the context of multiple social vulnerabilities. Our findings did not differ from previous studies affirming the associations between SES and education with laryngeal cancer prognosis, as covered in the SES theme score [15, 25].

Considering the detrimental mortality trends of laryngeal cancer seen in this study and overall in the US, our study provides a means of identifying the sociodemographic risk factors patients face pertaining to decreased survival and surveillance time. It is well documented that laryngeal neoplasms present later due to poor screening methods [26]. Aligned with this pattern, this study shows that social vulnerability associates with these disparate outcomes and provides an argument of how these factors should be taken into account when evaluating a patient’s risk for laryngeal cancer, especially in regards to disease management. Given the differences in therapy receipt related to social vulnerabilities, which have been shown to be a point of health disparity in patients with laryngeal cancer [17, 22]. Although our study did not specifically examine the use of laryngeal preservation therapies, we demonstrated that increasing social vulnerability was associated with decreased odds of radiation, a hallmark of salvage therapy [27]. By accounting for the complex interactions of SDoH, our use of the SVI can help inform health professionals of which social vulnerabilities need more investigation and guidance on how they can be used to inform policy and guidelines in managing complex and aggressive diseases like laryngeal cancer.

By utilizing large data and interactive SDoH approaches, modeling of sociodemographic factors in health disparities more accurately mirrors the real-world impact of manifold sociodemographic factors. With such progress, the question becomes less of what the problems are and more of how to take action against these specifically quantified targets [6, 28, 29]. As indicated by the degree of systemic factors affecting health outcomes, disparities affecting communities largely originate from public, private, and other institutions that make up the surroundings of patients. With these systemic origins, ameliorating community-based SDoH requires reshaping policies across the clinical and non-clinical spectrum, whether that includes neighborhood redistricting, increased subsidies of transportation and health insurance, publicly supported construction of food accessibility and affordable shelter, private-organization outreach, lobbying, and other initiatives [30, 31]. However, as national policy has begun to adopt approaches of addressing laryngeal cancer and other oncologic needs on a large scale, nuanced approaches and discourse of investigations like ours will enable careful resource allocation towards specific SDoH that present the most demonstrated need for support [32]. Next steps necessitate a calculated approach to initiating prospective implementations from large-data retrospective data in local contexts to provide proof of concept for nation-wide initiatives.

Strengths and Limitations

The foremost strength of this study lies in the use of the SVI to assess a wide range of social vulnerabilities that provide both a breadth of comparative SDoH-measures and the depth of county-level specificity. Furthermore, it also provides quantifiable associative measures of each SDoH-theme for its contributions to overall vulnerability impact on patient outcomes. Other strengths include the large sample size made possible by the utilization of a national database.

However, certain limitations must be considered for this study. Clinicodemographic variables of interest were either unavailable or had substantial levels of missingness, leading to prohibition of further analyses the specific SEER dataset iteration. These include the lack of information into the type of surgical procedure and revisions performed, immunotherapy receipt, and cause-of-death missingness. In light of these shortcomings, utilization of proprietary clinical datasets that require paid-access with fuller cataloging of such detailed measures not all SDoHs are covered by the SVI variables, leaving unknown factors that could contribute to a patient’s overall vulnerability. These restrictions also apply to the SVI, which remains restricted to its 15 SDoH-variables of interest. Future studies should consider the creation of custom SDoH-indices that encompass SVI-related factors, as well as others not traditionally investigated. In addition, considerations of multilevel analyses encompassing individual- and community-level SDoH-factors should be incorporated in future studies to extend beyond this investigation’s largely community-level contexts, as more recent investigations have engaged with [11, 12]. Lastly, as with any large retrospective study, the findings purported here can only be inferred as associative rather than causative for the relationships observed among laryngeal cancer disparities.

Conclusion

This investigation provides comprehensive insights into how a wide variety of social vulnerabilities interact and influence laryngeal cancer prognosis and treatment disparities within the United States. Not only do our results remain consistent with prior SDoH-studies, they also dynamically contextualize prior findings with socioeconomic status and minority race/ethnicity through additional factor considerations within these themes as well as themes of housing, transportation, and household composition. Through incorporating a large-data, interactional approach of publicly available tools, our insights harken the growing public and private consortium vowing to ameliorate observed nationwide disparities of cancers. Only through the synergies of social disparities observed here can individuals, their local communities, and representative institutions cooperatively initiate the specific prospective investigations and policies to enact positive change for laryngeal cancer disparities.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NCI-SEER repository, https://seer.cancer.gov/, and CDC-SVI repository, https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/place-health/php/svi/index.html.

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:12–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21820.

Divakar P, Davies L. Trends in Incidence and Mortality of Larynx Cancer in the US. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;149:34–41. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2022.3636.

Batool S, Burks CA, Bergmark RW. Healthcare Disparities in Otolaryngology. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep. 2023;11:95–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-023-00459-0.

Baliga S, Yildiz VO, Bazan J, Palmer JD, Jhawar SR, Konieczkowski DJ, et al. Disparities in Survival Outcomes among Racial/Ethnic Minorities with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer in the United States. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15061781.

Taylor DB, Osazuwa-Peters OL, Okafor SI, Boakye EA, Kuziez D, Perera C, et al. Differential Outcomes among Survivors of Head and Neck Cancer Belonging to Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148:119–27. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2021.3425.

Liu Y, Zhong L, Puram SV, Mazul AL. Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status and Racial and Ethnic Survival Disparities in Oral Cavity and Laryngeal Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2023;32:642–52. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0963.

Shaikh N, Morrow V, Stokes C, Chung J, Fancy T, Turner MT, et al. Factors Associated With a Prolonged Diagnosis-to-Treatment Interval in Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;166:1092–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998221090115.

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. CDC SVI documentation 2018. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/documentation/SVI_documentation_2018.html.

Fei-Zhang DJ, Chelius DC, Patel UA, Smith SS, Sheyn AM, Rastatter JC. Assessment of Social Vulnerability in Pediatric Head and Neck Cancer Care and Prognosis in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:E230016. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.0016.

McCampbell L, Fei‐Zhang DJ, Chelius D, Rastatter J, Sheyn A. Analyzing County‐level Social Vulnerabilities of Head and Neck Melanomas in the United States. Laryngoscope. Published online June 21, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.30832.

Verma R, Fei-Zhang DJ, Fletcher LB, Fleishman SA, Chelius DC, Sheyn AM, et al. Multilevel Disparities of Sex-Differentiated Human Papilloma Virus-Positive Oropharyngeal Cancers in the United States. J Clin Med. 2024;13:6392. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216392.

Fei-Zhang DJ, Sethia R, Wang LW, Sheyn AM, D’Souza JN, Chelius DC, et al. (2025) Causal Assessments of Multilevel Social Determinant Factors on Meningioma Disparities in the US. Neuro-Oncol Pract. npaf020, https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npaf020.

Diaz A, Lindau ST, Obeng-Gyasi S, Dimick JB, Scott JW, Ibrahim AM. Association of Hospital Quality and Neighborhood Deprivation With Mortality After Inpatient Surgery Among Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2253620. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.53620.

Feit NZ, Wang Z, Demetres MR, Drenis S, Andreadis K, Rameau A. Healthcare Disparities in Laryngology: A Scoping Review. Laryngoscope. 2022;132:375–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/LARY.29325.

Chen AY, Fedewa S, Zhu J. Temporal Trends in the Treatment of Early- and Advanced-Stage Laryngeal Cancer in the United States, 1985-2007. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137:1017–24. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHOTO.2011.171.

Jayakrishnan TT, White RJ, Greenberg L, Colonias A, Wegner RE. Predictors of chemotherapy and its effects in early stage squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2019;5:445–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/LIO2.327.

Hou WH, Daly ME, Lee NY, Farwell DG, Luu Q, Chen AM. Racial disparities in the use of voice preservation therapy for locally advanced laryngeal cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138:644–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHOTO.2012.1021.

Morse E, Fujiwara RJT, Judson B, Mehra S. Treatment delays in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A national cancer database analysis. Laryngoscope. 2018;128:2751–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/LARY.27247.

Saini AT, Genden EM, Megwalu UC. Sociodemographic disparities in choice of therapy and survival in advanced laryngeal cancer. Am J Otolaryngol. 2016;37:65–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJOTO.2015.10.004.

Li H, Li EY, Kejner AE. Treatment modality and outcomes in larynx cancer patients: A sex-based evaluation. Head Neck. 2019;41:3764–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/HED.25897.

Misono S, Marmor S, Yueh B, Virnig BA. T1 glottic carcinoma: do comorbidities, facility characteristics, and sociodemographics explain survival differences across treatment? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152:856–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599815572112.

Shin JY, Truong MT. Racial disparities in laryngeal cancer treatment and outcome: A population-based analysis of 24,069 patients. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:1667–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/LARY.25212.

Chen AY, Schrag NM, Halpern M, Stewart A, Ward EM. Health Insurance and Stage at Diagnosis of Laryngeal Cancer: Does Insurance Type Predict Stage at Diagnosis? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:784–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHOTOL.133.8.784.

Chen S, Dee EC, Muralidhar V, Nguyen PL, Amin MR, Givi B. Disparities in Mortality from Larynx Cancer: Implications for Reducing Racial Differences. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:E1147–E1155. https://doi.org/10.1002/LARY.29046.

Chen AY, Halpern M. Factors predictive of survival in advanced laryngeal cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:1270–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHOTOL.133.12.1270.

Bevers T, El-Serag H, Hanash S, Thrift AP, Tsai K, Maresso KC, et al. Screening and Early Detection. Abeloff’s Clin Oncol. Published online January 1, 2020:375-398.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-47674-4.00023-2.

The Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group. Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1685–90. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199106133242402.

Cox SR, Daniel CL. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Laryngeal Cancer Care. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;9:800–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40615-021-01018-3. 2021 9:3.

Fei-Zhang DJ, Chelius DC, Sheyn AM, Rastatter JC. Large-data contextualizations of social determinant associations in pediatric head and neck cancers. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Published online September 15, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0000000000000931.

Winkfield KM, Regnante JM, Miller-Sonet E, González ET, Freund KM, Doykos PM. Development of an Actionable Framework to Address Cancer Care Disparities in Medically Underserved Populations in the United States: Expert Roundtable Recommendations. JCO Oncol Pr. 2021;17:e278–e293. https://doi.org/10.1200/op.20.00630.

American Association for Cancer Research. Overcoming Cancer Health Disparities Through Science-based Public Policy. https://cancerprogressreport.aacr.org/disparities/chd20-contents/chd20-overcoming-cancer-health-disparities-through-science-based-public-policy/.

The White House. Cancer Moonshot. https://www.whitehouse.gov/cancermoonshot/.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Brad DeSilva from the Ohio State University for his feedback on parts of the Discussion.

Funding

There were no sources of funding for this study. Dr. Osazuwa-Peters is a Scientific Advisor for Navigating Cancer and report funding from the NIH outside of the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DF-Z: Concept and design, Data acquisition and analysis, Data interpretation, Drafting, Critical revision for important intellectual content, Statistical analysis. CC: Concept and design, Data acquisition and analysis, Data interpretation, Drafting, Critical revision for important intellectual content. AH: Data interpretation, Critical revision for important intellectual content. AS: Data interpretation, Critical revision for important intellectual content. DL: Data interpretation, Critical revision for important intellectual content. UP: Data interpretation, Critical revision for important intellectual content. SS: Data interpretation, Critical revision for important intellectual content. AD: Data interpretation, Critical revision for important intellectual content. NO-P: Data interpretation, Critical revision for important intellectual content. JD: Concept and design, Data acquisition and analysis, Data interpretation, Drafting, Critical revision for important intellectual content, Supervision. AS: Concept and design, Data acquisition and analysis, Data interpretation, Drafting, Critical revision for important intellectual content, Supervision. JR: Concept and design, Data acquisition and analysis, Data interpretation, Drafting, Critical revision for important intellectual content, Supervision. DC: Concept and design, Data acquisition and analysis, Data interpretation, Drafting, Critical revision for important intellectual content, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Northwestern University IRB/ethics committee has exempted this study (STU00216871) due to the data queried consisting of publicly available, de-identified data. No consent to participate was necessitated due to the nature of this study comprising retrospective analyses of a publicly available, de-identified national database.

Consent to publication

The authors of this manuscript consent to the accuracy of the contents of this manuscript and approve for its submission to be published if accepted.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fei-Zhang, D.J., Cuenca, C.M., Haskins, A.D. et al. Assessments of social vulnerability on laryngeal cancer treatment & prognosis in the US. Br J Cancer 133, 248–254 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-025-03056-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-025-03056-8