Abstract

Background

Survival differences between socioeconomic groups in colorectal cancer have been studied for patients diagnosed in the 90s and 00s, but research on recent patients using individual measures of socioeconomic position is limited.

Methods

CRCBaSe, a database of linked national registry data, was used to analyse stage I–III colorectal cancer patients diagnosed in Sweden between 2008 and 2021. The exposures of interest were income and education. Flexible parametric survival models were fitted and standardised survival probabilities and hazard ratios (HR) were calculated for cancer-specific survival, recurrence, and overall survival.

Results

Analysis of 59,995 patients showed better 5-year standardised cancer-specific survival in the least deprived income group, 77.8% (95%CI 76.9–78.6) vs. 73.2% (95%CI 72.6–73.9) in the most deprived income group, HR 0.93 (95%CI 0.87–0.99). Time to recurrence was not statistically different between socioeconomic groups. Overall survival was better in the least deprived income group, with a 5-year standardised overall survival of 70.0% (95%CI 69.1–70.8) vs. 63.5% (95%CI 62.9–64.1) in the most deprived income group, HR 0.82 (95%CI 0.79–0.86).

Conclusion

We found large disparities in cancer-specific and overall survival between the highest and most deprived income and education groups, despite improvements in care and the introduction of guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Is the prognosis after colorectal cancer (CRC) resection dependent upon socioeconomic position (SEP) in a modern material? Previous studies show a substantial variation in CRC survival by SEP, age and to some extent sex [1, 2]. Differences by SEP persist even in countries with universal healthcare access and irrespective of how deprivation is defined, with the most deprived individuals having the worst prognosis. Many studies on the subject have been performed before the introduction of national and international guidelines, and the establishment of national quality registries. This has also been the case in Sweden where regional guidelines existed in the late 00s and national guidelines were introduced in 2016 [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. The quality of care has improved during the last decades and evaluations based on earlier data are probably not representative of the current practices [10, 11]. Today, nearly all elective colorectal cancer patients are discussed at preoperative multidisciplinary team conferences (MDT), yet differences in treatment remain [12, 13].

The most deprived are more likely to have emergency surgery [3, 12] and differences can be seen across SEP for oncological, surgical treatment [12, 14, 15], and outcomes [16]. In data from England, relative survival differences of 10% between socioeconomic groups have been observed [17]. Some of this is explained by differences in prognostic factors [18], but it is unlikely to be entirely through such factors [19]. Most previous studies have focused on overall survival, which captures both the effect of recurrences and mortality from other causes, without distinguishing these two [20]. Cancer-specific survival is useful for assessing the risks and benefits of treatment while recurrence rates or time to recurrence measures if the cancer treatment was successful and highlights treatment and stage differences between groups.

This study aimed to investigate differences in time to recurrence, cancer-specific survival, and overall survival for stage I–III CRC in Sweden across socioeconomic groups. The hypothesis was that the most deprived have more recurrences and worse survival outcomes despite improvements in the quality of care.

Materials and methods

The study was approved by the Regional Board of the Ethical Committee in Stockholm (DNR: 2014/71-31, 2018/328-32) and by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (DNR: 2021-00342, 2023-03305-02).

Patient data

Patient data originated from the Colorectal Cancer Database (CRCBaSe), a register-linkage of the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry (SCRCR) and national registries at the National Board of Welfare and Statistics Sweden described in more detail elsewhere [21, 22]. Registry data were linked using the Swedish personal identification number, the unique number issued to everyone living in Sweden.

All adults (≥18 years old) with a resected stage I–III CRC in CRCBaSe with a first-time diagnosis between 2008 and 2021 were included in the study.

Exposures

SEP was defined based on two indicators, the individual part of disposable household income and the highest education achieved, with income being the main exposure of interest. These variables are collected by Statistics Sweden yearly from other government agencies. The average individual part of disposable household income 2 years before diagnosis was split into sex and age-specific quartiles to allocate patients in groups of high and low socioeconomic positions (cut-points in Supplementary Table 1). The quartiles were created separately for patients above and below 65 years of age of the same sex with income quartile 1 (Q1) being the most deprived, and income quartile 4 (Q4) being the least deprived. The highest level of education attained at diagnosis was categorised as <9 years, 9–12 years and >12 years, with <9 years corresponding to the least educated (and most deprived) and >12 years to the most educated (least deprived).

Outcomes

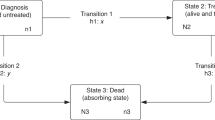

The outcomes of interest were time to recurrence (TTR) from surgery and cancer-specific survival (CSS) from diagnosis. In addition, overall survival (OS) was investigated [20]. Follow-up for TTR was set to 6.5 years after diagnosis since the mandatory reporting to the registry stops at 5 years (with some delay). Cases with events or follow-up beyond this period were censored at 6.5 years.

Other covariates

Civil status at diagnosis was classified into two categories (living alone or not) reported by Statistics Sweden based on registered marriages, divorces, partnerships and cohabitation information from the census. For those with missing information on civil status, individual and household income data was used to infer their civil status. Specifically, patients with a ratio of individual income to weighted household income smaller than 0.9 or larger than 1.1 were reclassified as living with someone even if they were unmarried or not in a registered partnership.

Comorbidities were measured using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [23] calculated before cancer diagnosis from the National Patient Registry, containing all diagnoses from in- and outpatient care since the 1980s [24]. In addition, the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification (ASA) reported in the SCRCR and based on the preoperative anaesthesia evaluation was included [25]. Compared to the Charlson comorbidity index, the ASA classification captures functional limitations instead of relying solely on previous diagnoses.

Age at diagnosis, sex, year of diagnosis, tumour location and pT and pN stage was obtained from the SCRCR and included as confounders in the models.

Statistical methods

No power analysis was performed since the study design called for using all available cases in the CRCBaSe. Complete case analysis was used since there were few cases with missing data for the exposures, covariates and outcomes. Demographics were obtained by income and education and presented as the number of patients in each group and the proportion in each group. Kaplan–Meier graphs for OS by income and education groups including the number at risk throughout follow-up were drawn, corresponding to unadjusted estimates.

Data were analysed using flexible parametric survival models (FPM) with 4 knots for the baseline hazard shape to adjust for confounding [26, 27]. Knots were placed at equally distributed quantiles of the log of the event times. Direct acyclic graphs were used to assess potential confounders (Supplementary Fig. 1). Separate FPM were fitted for each of the exposures of interest (income and education) and these were adjusted for civil status (partner/no), year of diagnosis (year), sex (male/female), age (continuous with restricted cubic splines to allow a non-linear effect of age with 3 knots), Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI, continuous) [23], American Society of Anesthesiologists classification (ASA, categorised 1–5) [25], T (1–4) and N (0–2) stage and tumour location (colon/rectum) to get stage adjusted estimates. Estimates without adjusting for the stage (T-stage and N-stage) and comorbidities (CCI and ASA) were produced separately to assess the role of the mediators (this corresponds to the adjustment set without potential mediators).

Five models using all available data were fitted for each outcome and adjustment set (with and without the adjustment for mediators stage and comorbidities): (1) without exposures, (2) with income, (3) with education, (4) with a time-varying effect (i.e., non-proportional hazards) for income (5) with a time-varying effect for education. Models within each adjustment set were compared using the likelihood ratio test to test the statistical significance of the exposure of interest (by comparing model 2–5 to model 1) and test for time-varying effects (by comparing model 4 to model 2 and model 5 to model 3). Based on the likelihood ratio test, the best models for income and education (i.e., with or without time-varying effects) were used to obtain marginal estimates, i.e., standardised survival curves under the least and most deprived groups using the adjustment sets described in the previous paragraph.

Survival estimates and Hazard ratios (HR) of recurrence, cancer-specific mortality and all-cause mortality, were obtained from the models as they provide distinct insights. HRs compare the rates of experiencing an outcome across different income or education groups, while survival probabilities indicate the risk of experiencing the event within a specific timeframe [28]. Different income and education groups have different covariate distributions that can explain part of the survival differences. The HRs are adjusted for the covariate distribution (the adjustment sets described previously), and it is therefore assumed that the relative difference in rates is the same within each covariate pattern. However, this is not the case for the survival function since it is an absolute measure and will be different for each covariate pattern. To make fairer comparisons, standardised survival functions were therefore obtained. Different choices can be made in terms of which population is used as the “standard“ population [28]. In the present study, the covariate pattern observed in the most deprived (i.e., lowest income or education group) was used. For the analysis, flexible parametric survival models were fitted by including all patients and adjusting for all covariates. Then, standardised survival estimates were obtained based on these model parameters and using the covariate pattern of the most deprived as the standard. We obtained the standardised survival functions under the highest and under the lowest deprivation, and these can be interpreted as the observed survival of the most deprived and the survival that the most deprived would have if they had belonged to the least deprived group, respectively. HR and standardised survival proportions were calculated at 1, 3 and 5 years for TTR and at 1, 3, 5 and 10 years for CSS and OS. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistics were calculated using R (version 4.3.2; R Core Team 2023) [29] and the rstpm2 package [30, 31] was used to produce FPM and calculate HR, rates and survival curves.

Results

There were 89,107 patients diagnosed with first-time CRC between 2008 and 2021 included in the database. After the exclusion of 18,925 patients with synchronous metastatic disease, 1864 patients without pathological stage information, 7818 where no resection was performed and 505 individuals who were classified as stage 0 in the registry the final cohort contained 59,995 patients where the most advanced tumour (highest T and N stage) was used in cases of multiple tumours diagnosed on the same day (Supplementary Fig. 2). There were 56,204 patients with data on income and 55,584 with data on education. Patients who did not have surgery were older, more comorbid and had lower income and less education than patients who had surgery (Supplementary Table 2).

Patient and tumour characteristics

The patients in the most deprived income (Q1) or least education (<9 years) groups were older, more comorbid (proportion of ASA3 and ASA4 38.7% vs. 25.2% in most vs. least deprived for income), and more often lived alone. In this group, colon cancer was more common (72.2% vs. 68.1% in least vs. most deprived for income) as were, higher malignancy grade, mucinous features, emergency surgery, more postoperative complications, and less neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment. In addition, patients with the most deprived income had higher T-stage (18.1% T4 vs. 16.6% in the least deprived) and were more often node-positive. In those with the least education, T3 and node-negative tumours (N0) were more common, whereas vascular and perineural invasion were less common. See Tables 1 (Demographics) and 2 (Tumour characteristics) for details.

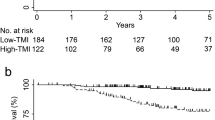

Unadjusted estimates of mortality

The median follow-up until censoring or death was 4.9 years. Unadjusted estimates for OS in the form of Kaplan–Meier curves along with the number at-risk table to illustrate censoring for OS are presented in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4. In these unadjusted analyses, the most deprived had worse survival than the least deprived.

Recurrences

Neither income nor education was statistically significantly associated with TTR in the multivariable models. Models with time-varying effects did not yield a better fit and were therefore not used.

There was no difference in the standardised probability of patients being recurrence-free at 5 years (82.2% in income Q1 vs. 82.3% in income Q4), Supplementary Fig. 5 and Table 3. Results were similar when omitting tumour characteristics, Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 3, and comorbidities, another potential mediator, from the model, Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 4.

Similarly, the standardised probability of being recurrence-free at 5 years in the least and the most educated groups was 82.5% and 82.4%, respectively, Supplementary Fig. 5 and Table 3. Results were similar when omitting tumour characteristics, Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 3, and comorbidities from the model, Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 4. The HR for recurrence rates was 0.99 (95%CI 0.92–1.05) for income Q4 vs. Q1 and 1.01 (95%CI 0.95–1.07) for >12 years vs. <9 years of education. Similar results were seen when omitting tumour characteristics and comorbidities, Supplementary Tables 5 and 6.

Cancer-specific survival

Both income and education were statistically significantly associated with cancer-specific mortality within their respective models (Likelihood ratio test p < 0.001 for both income and education). Time-varying effects for income and education were also statistically significant (Likelihood ratio test p < 0.001 for both income and education) and so the models with time-varying effects were used to calculate adjusted survival and HR for CSS.

The 5-year standardised CSS was 73.2% (95%CI 72.6–73.9) in income Q1, and the standardised CSS estimate had they been in the least deprived income group, Q4, was 77.8% (95%CI 76.9–78.6), resulting in a difference of 4.6 percentage points between income groups, Fig. 1 and Table 3. Omitting tumour characteristics from the model, the difference in 5-year standardised CSS was 5.3% between the most and least deprived income groups, Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 3. Omitting tumour characteristics and comorbidities from the model, the difference in 5-year standardised CSS was 6.1% between the most and least deprived income groups, Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 4.

Left panel: Income, Right panel: Education. Adjusted to the distribution of civil status, year of diagnosis, sex, age, CCI, ASA, T and N stage and tumour location of the most deprived. Least deprived: Income Q4. Most deprived: Income Q1. Most educated: >12 years of education. Least educated: <9 years of education.

Similarly, the 5-year standardised CSS by education were 76.5% (95%CI 75.6-77.3) in those with <9 years of education and 79% (95%CI 78.2–79.9) with >12 years of education, resulting in a 2.5 percentage points difference between education groups, Fig. 1 and Table 3. Omitting tumour characteristics from the model, the difference in 5-year standardised CSS was 2.9% between the least and most educated, Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 3. Omitting tumour characteristics and comorbidities from the model, the difference in 5-year standardised CSS was 3.3% between the least and most educated, Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 4. Overall, differences in CSS between the groups increased during the first 5 years and then decreased (for income group) or stabilised (for education groups).

The HR for CSS at 1 year was 0.76 (95%CI 0.71–0.82) in income Q4 vs. Q1 and 0.86 (95%CI 0.80–0.91) for >12 years vs. <9 years of education. HRs at 3, 5 and 10 years moved towards 1 over time, Table 4. When omitting tumour characteristics, the 1-year HR was 0.74 (95%CI 0.68–0.79) in income Q4 vs. Q1 and 0.84 (95%CI 0.78–0.89) for >12 years vs. <9 years of education, Supplementary Table 5. Differences between income and education groups were increased when omitting stage and comorbidities from the models, with the 1-year HR at 0.70 (95%CI 0.65–0.75) for income Q4 vs. Q1 and 0.81 (95%CI 0.76–0.86) for >12 years vs. <9 years of education, Supplementary Table 6.

Overall survival

Both income and education were statistically significantly associated with all-cause mortality within their respective models (Likelihood ratio test p < 0.001 for both income and education). Time-varying effects for income and education were also statistically significant (Likelihood ratio test p 0.001 and <0.001 for income and education, respectively) and so the models with time-varying effects were used to calculate adjusted survival and HR for OS.

The standardised 5-year OS by income were 63.5% (95%CI 62.9–64.1) in income Q1 and 70.0% (95%CI 69.1–70.8) in income Q4, Fig. 2 and Table 3. Omitting tumour characteristics from the model, the difference in 5-year standardised OS was 6.9% between the least and most deprived income groups, Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 3. Omitting tumour characteristics and comorbidities from the model, the difference in 5-year standardised OS was 8.3% between the least and most deprived income group, Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Table 4.

Left panel: Income, Right panel: Education. Adjusted to the distribution of civil status, year of diagnosis, sex, age, CCI, ASA, T and N stage and tumour location of the most deprived. Least deprived: Income Q4. Most deprived: Income Q1. Most educated: >12 years of education. Least educated: <9 years of education.

The standardised 5-year OS by education was 67.7% (95%CI 66.8–68.6) in those with <9 years of education and 71.4% (95%CI 70.5–72.3) for >12 years of education, Fig. 2 and Table 3. The differences in OS between groups increased with time, and contrary to what was seen with CSS there was no plateau. Omitting tumour characteristics from the model, the difference in 5-year standardised OS was 3.8% between the least and most educated, Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 3. Omitting tumour characteristics and comorbidities from the model, the difference in 5-year standardised OS was 4.5% between the least and most educated, Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Table 4.

The adjusted HR for OS at 1 year were 0.82 (95%CI 0.79–0.86) in income Q4 vs. Q1 and 0.84 (95%CI 0.81–0.87) for >12 years vs. <9 years of education. HRs at 3, 5 and 10 years remained stable for income and decreased for education, Table 3. The 1-year HRs were 0.77 (95%CI 0.72–0.81) for income Q4 vs. Q1 and 0.90 (95%CI 0.85–0.95) for >12 years vs. <9 years of education when omitting tumour characteristics, Supplementary Table 5. When omitting tumour and comorbidities, differences between income groups were larger with a 1-year HR at 0.72 (95%CI 0.67–0.76) for income Q4 vs. Q1 and 0.86 (95%CI 0.81–0.90) for >12 years vs. <9 years of education, Supplementary Table 6.

Discussion

In this nationwide cohort study of 59,995 CRC patients with curatively treated stage I–III disease, we show that differences in survival by SEP persist in a modern material. The most deprived (based on income) have 6.5% lower standardised 5-year overall survival. The biggest differences between income and education groups were seen for standardised OS, while there were smaller differences for standardised CSS between income groups. However, differences between the least and most deprived remained above 4 percentage points during follow-up. Interestingly, there was no difference in time to recurrence after adjusting for demographic and tumour factors. This suggests that the survival differences between socioeconomic groups are not necessarily driven by an increased risk of recurrence in the most deprived, besides differences in stage and comorbidities.

The standardised CSS comparing the least to the most deprived in terms of income decreased after 5 years, suggesting that complications from treatment and early recurrences could be partly responsible for the larger early difference between deprivation groups. The difference in standardised OS between those with most and least education increased with time, suggesting that education matters more with time since diagnosis. Income is thought to measure the ability to maintain a healthier lifestyle and affect psychosocial determinants of health, which seem more important in short-term survival after cancer diagnosis [32, 33]. Education is associated with health awareness and the ability to access health care and appears to be more important in long-term survival [33, 34].

CSS captures mortality related to CRC diagnosis, and TTR captures recurrences in the absence of death which might explain the lack of an effect on TTR despite previously explored treatment differences [12]. The cancer care may be equal but unable to compensate for preexisting differences between the groups. Overall, the most deprived patients may be at a higher risk of non-related cancer death due to poorer health, which might compete with the risk of recurrences. There might also be a difference in survival after recurrences explaining part of the differences in CSS between socioeconomic groups. Another explanation could be that more advanced metastatic disease upon diagnosis of recurrence in the most deprived, paralleling the observed more advanced stage at diagnosis. Other potential explanations are lower treatment tolerance or worse general health increasing the risk of complications in the most deprived.

We have previously shown that there are differences in treatment in non-metastatic colorectal cancer according to SEP, even after adjusting for the differences in age, comorbidities, tumour location and staging [35], a difference that is also present in patients with recurrences. Recent studies have shown differences in the treatment and survival of synchronous metastatic disease between men and women [36], access to surgery for metastatic disease between parts of the country, SEP [37,38,39], and differences in loss of life expectancy by income [13].

Patients in the most deprived income quartile had a 6.5% lower standardised OS at 5 years, which echoes results from England where relative survival was investigated [17]. In a previous Swedish study of rectal cancer patients diagnosed in 1995–2005, the HR of death in resected patients comparing income Q1 vs. Q4 was 1.35 (0.74 if reversing the ratio) suggesting that disparities have not decreased over time [16].

Strengths and limitations

The SCRCR covers at least 99% of all diagnosed CRC in Sweden and was recently validated [35, 40]. All patients who had surgery for a non-metastasised CRC were included resulting in a large sample size reflective of practice in Sweden, and likely generalisable to other European countries with similar healthcare systems. Data from national registries allow near complete follow-up due to personal identification numbers allowing linkage of information. Previous validation of the national cause of death registry and patient registry indicates that severe disease and malignant diseases are captured to a high degree [41, 42]. Autopsy rates in Sweden are low which could lead to missed recurrences [43]. However, there is no apparent SEP-dependent difference in the correctness of cause of death registration in Sweden [44], but autopsy rates have not been evaluated in relation to SEP. Previous studies on SEP and CRC were performed before the national care guidelines and do not reflect practice today. This study included more recently diagnosed patients, but given the follow-up needed, it is difficult to evaluate discrepancies in real time.

The analysis is limited to what is registered and the reasons and causes for differences cannot be ascertained. The individual part of disposable household income was chosen over individual disposable income to capture income deprivation for those not working or those working and supplying others. Previous research has shown that the most deprived have worse health overall and survival in the general population [45]. Information on tobacco use and performance status was not available, which could have an impact on survival and eligibility for treatment. The missing data in this setting would be challenging to impute, e.g. imputing the education status of individuals with missing data based on the observed data requires strong assumptions. This could lead to biased imputed values and potential misclassification in education groups and, consequently, biased estimates of interest [46]. National screening for CRC started in 2023 after the patients were included in this study but regional screening in one healthcare region has been running since 2008. In the future, screening may impact the rate of emergency surgery, the stage distribution and possibly reduce the difference in recurrence rates. Unfortunately, those with low SEP have lower participation in screening [47].

Conclusion

In this material spanning 14 years with an average of 5 years of follow-up, there was no difference in TTR, but there were large disparities in both CSS and OS between the least and most deprived income groups and between the most and least educated. Further investigation is required to understand the reasons for these disparities. Efforts to improve screening participation and detection of disease early for the most deprived, and to improve public health for all may impact some disparities.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry, Swedish National Board of Welfare, and Statistics Sweden. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. The statistical code used to produce the results is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hussain SK, Lenner P, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. Influence of education level on cancer survival in Sweden. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:156–62.

Abdoli G, Bottai M, Moradi T. Cancer mortality by country of birth, sex, and socioeconomic position in Sweden, 1961–2009. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e93174.

Gunnarsson H, Ekholm A, Olsson LI. Emergency presentation and socioeconomic status in colon cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:831–6.

Sjövall A, Blomqvist L, Martling A. Pretreatment staging of colon cancer in the Swedish population. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1361–6.

Cavalli-Björkman N, Lambe M, Eaker S, Sandin F, Glimelius B. Differences according to educational level in the management and survival of colorectal cancer in Sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1398–406.

Sjöström O, Dahlin AM, Silander G, Syk I, Melin B, Hellquist BN. Travel time to care does not affect survival for patients with colorectal cancer in northern Sweden: a data linkage study from the Risk North database. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0236799.

Pavlidis N, Stahel R, Hansen H, Cervantes A. Fourteen years of evolution of ESMO Guidelines: from the minimum recommendations to the Consensus Conference-derived guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:vi7–11.

Konradsen AA, Lund CM, Vistisen KK, Albieri V, Dalton SO, Nielsen DL. The influence of socioeconomic position on adjuvant treatment of stage III colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 2020;59:1291–9.

Coughlin SS. Social determinants of colorectal cancer risk, stage, and survival: a systematic review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35:985–95.

Lindskog EB, Gunnarsdóttir KÁ, Derwinger K, Wettergren Y, Glimelius B, Kodeda K. A population-based cohort study on adherence to practice guidelines for adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:948.

Rosander E, Holm T, Sjövall A, Hjern F, Weibull CE, Nordenvall C. Preoperative multidisciplinary team assessment is associated with improved survival in patients with locally advanced colon cancer; a nationwide cohort study in 3157 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47:2398–404.

Osterman E, Syriopoulou E, Martling A, Andersson TM-L, Nordenvall C. Despite multi-disciplinary team discussions the socioeconomic disparities persist in the oncological treatment of non-metastasized colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2024;199:113572.

Syriopoulou E, Osterman E, Miething A, Nordenvall C, Andersson TM-L. Income disparities in loss in life expectancy after colon and rectal cancers: a Swedish register-based study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2024;78:402.

Olsson LI, Granström F, Glimelius B. Socioeconomic inequalities in the use of radiotherapy for rectal cancer: a nationwide study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:347–53.

Olsson LI, Granström F, Påhlman L. Sphincter preservation in rectal cancer is associated with patients’ socioeconomic status. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1572–81.

Olsson LI, Granstrom F. Socioeconomic inequalities in relative survival of rectal cancer most obvious in stage III. World J Surg. 2014;38:3265–75.

Syriopoulou E, Morris E, Finan PJ, Lambert PC, Rutherford MJ. Understanding the impact of socioeconomic differences in colorectal cancer survival: potential gain in life-years. Br J Cancer. 2019;120:1052–8.

Wrigley H, Roderick P, George S, Smith J, Mullee M, Goddard J. Inequalities in survival from colorectal cancer: a comparison of the impact of deprivation, treatment, and host factors on observed and cause specific survival. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:301–9.

Lyratzopoulos G, West CR, Williams EMI. Socioeconomic variation in colon cancer tumour factors associated with poorer prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:828–30.

Punt CJA, Buyse M, Köhne C-H, Hohenberger P, Labianca R, Schmoll HJ, et al. Endpoints in adjuvant treatment trials: a systematic review of the literature in colon cancer and proposed definitions for future trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:998–1003.

Weibull CE, Boman SE, Glimelius B, Syk I, Matthiessen P, Smedby KE, et al. CRCBaSe: a Swedish register-based resource for colorectal adenocarcinoma research. Acta Oncol. 2023;62:342–9.

Ludvigsson JF, Svedberg P, Olén O, Bruze G, Neovius M. The longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and its use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34:423–37.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Ludvigsson JF, Appelros P, Askling J, Byberg L, Carrero J-J, Ekström AM, et al. Adaptation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index for register-based research in Sweden. Clin Epidemiol. 2021;13:21–41.

Fitz-Henry J. The ASA classification and peri-operative risk. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93:185–7.

Royston P, Lambert PC Flexible parametric survival analysis using Stata: beyond the Cox model. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2011.

Syriopoulou E, Mozumder SI, Rutherford MJ, Lambert PC. Robustness of individual and marginal model-based estimates: a sensitivity analysis of flexible parametric models. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;58:17–24.

Syriopoulou E, Wästerlid T, Lambert PC, Andersson TM-L. Standardised survival probabilities: a useful and informative tool for reporting regression models for survival data. Br J Cancer. 2022;127:1808–15.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023. https://www.R-project.org/.

Liu X-R, Pawitan Y, Clements M. Parametric and penalized generalized survival models. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27:1531–46.

Liu X, Pawitan Y, Clements MS. Generalized survival models for correlated time-to-event data. Stat Med. 2017;36:4743–62.

Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. Income inequality and population health: a review and explanation of the evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1768–84.

Galobardes B. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:7–12.

Khalatbari-Soltani S, Maccora J, Blyth FM, Joannès C, Kelly-Irving M. Measuring education in the context of health inequalities. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51:701–8.

Osterman E, Hammarström K, Imam I, Osterlund E, Sjöblom T, Glimelius B. Completeness and accuracy of the registration of recurrences in the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry (SCRCR) and an update of recurrence risk in colon cancer. Acta Oncol. 2021;60:842–9.

Osterlund E, Glimelius B. Temporal development in survival, and gender and regional differences in the Swedish population of patients with synchronous and metachronous metastatic colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2022;61:1278–88.

Ljunggren M, Weibull CE, Palmer G, Osterlund E, Glimelius B, Martling A, et al. Sex differences in metastatic surgery following diagnosis of synchronous metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2022:152:363–73.

Ljunggren M, Weibull CE, Rosander E, Palmer G, Glimelius B, Martling A, et al. Hospital factors and metastatic surgery in colorectal cancer patients, a population-based cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:907.

Vallance AE, van der Meulen J, Kuryba A, Braun M, Jayne DG, Hill J, et al. Socioeconomic differences in selection for liver resection in metastatic colorectal cancer and the impact on survival. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:1588–94.

Moberger P, Sköldberg F, Birgisson H. Evaluation of the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry: an overview of completeness, timeliness, comparability and validity. Acta Oncol. 2018;57:1611–21.

Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim J-L, Reuterwall C, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450.

Johansson LA, Westerling R. Comparing Swedish hospital discharge records with death certificates: implications for mortality statistics. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:495–502.

Rosendahl A, Mjörnheim B, Takman C, Eriksson LC. The clinical value of autopsies at a university hospital in Sweden. Nord J Nurs Res. 2017;37:119–26.

Kulhánová I, Menvielle G, Bopp M, Borrell C, Deboosere P, Eikemo TA, et al. Socioeconomic differences in the use of ill-defined causes of death in 16 European countries. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1295.

Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam A-JR, Schaap MM, Menvielle G, Leinsalu M, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2468–81.

Hughes RA, Heron J, Sterne JAC, Tilling K. Accounting for missing data in statistical analyses: multiple imputation is not always the answer. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48:1294–304.

Strömberg U, Peterson S, Holmén A, Holmberg E, Hultcrantz R, Martling A, et al. Rational targeting of population groups and residential areas for colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;60:23–30.

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible by the continuous work of steering groups of the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Register (SCRCR) and Colorectal Cancer Base Sweden (CRCBaSe). We also thank Sol Erika Boman and Ida Hed Myrberg for their help with the database and analysis tools, and Professor Bengt Glimelius for his valuable input on the analysis plan.

Funding

The study was supported financially by the Ihre Foundation and Swedish Medical Society [grant number SLS-972711], Gävleborg County Council [grant number CFUG-978856], Swedish Research Council for Health Working Life and Welfare [grant number 2022-00898], the Swedish Cancer Society [grant number 22-2126], the Stockholm Cancer Society, the Swedish Cancer and Allergy Foundation and supported by the Regional Agreement on Medical Training and Clinical Research (ALF) between the Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institute. Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Erik Osterman: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft. Elisavet Syriopoulou: conceptualisation, methodology, writing—review and editing. Anna Martling: resources, supervision, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing. Therese M.-L. Andersson: conceptualisation, methodology, writing—review and editing. Caroline Nordenvall: resources, supervision, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Regional Board of the Ethical Committee in Stockholm (DNR: 2014/71-31, 2018/328-32) and by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (DNR: 2021-00342, 2023-03305-02). Informed consent was obtained from patients to be included in the SCRCR for quality and research purposes. The need for additional approval was waived. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Osterman, E., Syriopoulou, E., Martling, A. et al. Impact of socioeconomics on recurrences and survival in non-metastasized colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 133, 1854–1863 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-025-03224-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-025-03224-w