Abstract

Radiation-induced colitis is a common clinical problem after radiation therapy and accidental radiation exposure. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) have immunosuppressive functions that use a variety of mechanisms to alter both the innate and the adaptive immune systems. Here, we demonstrated that radiation exposure in mice promoted the expansion of splenic and intestinal MDSCs and caused intestinal inflammation due to the increased secretion of cytokines. Depletion of monocytic MDSCs using anti-Ly6C exacerbated radiation-induced colitis and altered the expression of inflammatory cytokine IL10. Adoptive transfers of 0.5 Gy-derived MDSCs ameliorated this radiation-induced colitis through the production IL10 and activation of both STAT3 and SOCS3 signaling. Intestinal-inflammation recovery using 0.5 Gy-induced MDSCs was assessed using histological grading of colitis, colon length, body weight, and survival rate. Using in vitro co-cultures, we found that 0.5 Gy-induced MDSCs had higher expression levels of IL10 and SOCS3 compared with 5 Gy-induced MDSCs. In addition, IL10 expression was not enhanced in SOCS3-depleted cells, even in the presence of 0.5 Gy-induced monocytic MDSCs. Collectively, the results indicate that 0.5 Gy-induced MDSCs play an important immunoregulatory role in this radiation-induced colitis mouse model by releasing anti-inflammatory cytokines and suggest that IL10-overexpressing mMDSCs may be potential immune-therapy targets for treating colitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Radiotherapy generates free radicals in the exposed cells and tissues, resulting in DNA damages in various organs [1]. Patients receiving radiation to treat a pelvis-abdomen-thoracic malignancy commonly experience gastrointestinal side effects, including radiation colitis, radiation mucositis, and pelvic radiation disease [2]. The pathogenesis of radiation-induced colitis consists of many inflammatory components of the intestine, including the epithelial barrier, cytokine expression, deregulation of the immune response, and leukocytes recruitment [3, 4]. Radiation exposure recruited and expanded Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) through the increased expression of various pro-inflammatory cytokines. MDSCs play a critical role in the body’s response to this increased inflammation during colitis, with a paradoxical immunomodulatory activity that apparently exacerbates the disease [5, 6]. MDSCs represent a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells (IMCs) that are precursors to granulocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages at early stages of differentiation [7]. These cells are distinguished from other bone-marrow cell types in that they are known to have strong immunosuppressive properties rather than being immunostimulating. Clinical studies have revealed that the imbalance of MDSC fraction is correlated with disease severity in ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. In particular, MDSC levels are elevated in T cell-dependent colitis which serves to protect mice from developing intestinal inflammation [6]. Furthermore, accumulating evidence indicates that MDSC can be a therapeutic target to relieve the inflammatory burden of the patients under radiotherapy.

In mice, MDSCs are commonly identified as co-expressing the cell surface markers CD11b and GR1. Two distinct subsets of MDSCs have been identified, granulocytic MDSCs (gMDSCs: CD11b+ , Ly6G+, and Ly6Clow) and monocytic MDSCs (mMDSCs: CD11b+ , Ly6G-, and Ly6Chigh), which can be differentiated from each other according to GR1-antibody recognition of the Ly6G and Ly6C epitopes [8, 9]. It is possible that MDSC subsets, defined by specific cell-surface phenotypes, may express different biochemical-suppression mediators or simply different mediator amounts under different pathological conditions [10]. These MDSC subsets may also function differently by using distinct mechanisms to suppress T cells in a disease-dependent manner. The accumulation of MDSCs is tightly correlated with the regulation of chronic inflammation and the immune responses against cancer and infections [11]. However, some studies have shown that the adoptive transfer of MDSCs has an anti-inflammatory effect in diseases with chronic inflammation and that pharmacological depletion of MDSCs significantly exacerbates both inflammation and pathological cardiac remodeling [12, 13]. In addition, a positive feedback loop between MDSCs and T cells via TGF-β signaling has been shown to inhibit intestinal inflammation in a murine colitis model [14].

MDSC immunosuppressive activity and proliferation are both regulated by a crucial transcription factor: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) [15]. Activated STAT3 not only drives the transcription of many genes related to cell proliferation, function, and survival, but it also induces the transcription of suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) genes [16]. The SOCS3 protein is one family member that attenuates cytokine signal transduction in response to signals from a diverse range of cytokines and growth factors. Current evidence indicates that intracellular Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT signaling not only governs cytokine-induced immunological responses but also rapidly initiates SOCS3 expression and its biological functions [17, 18]. This signaling can regulate a variety of cytokine functions and is involved in the development of many diseases (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis) and acts as a general driver of chronic inflammation [19]. The importance of SOCS3 in inflammatory bowel disease has been highlighted by studies documenting its involvement in all stages of disease development [20]. Given the different roles of SOCS3 in different diseases, further SOCS3 studies are expected to provide important new insights into their pathophysiologies and possible therapeutic strategies.

Here, we examined population changes in MDSCs in response to radiation exposure and investigated their immune-modulatory functions using a murine model of radiation-induced colitis. In addition, we explored the anti-inflammatory signaling mechanism of the IL10/STAT3/SOCS3 axis in this radiation-induced inflammation.

Results

Radiation increases intestinal inflammation accompanied by MDSC expansion

Inflammatory responses in intestinal tissue are characterized by weight loss, crypt damage, epithelial-layer defects, and leukocyte infiltration [21]. For the present disease model, mice were exposed to radiation at 2.5 Gy three times during a one-week period (Fig. S1A). This irradiation induced the upregulation of inflammatory cytokines (Fig. S1B), loss of body weight, colon shortening, and high-grade inflammation in these mice 21 days after radiation exposure, and led to decreased survival (Fig. 1A). The accumulation of MDSCs is associated with inflammatory disease [22]. To examine whether radiation exposure increased the population of MDSCs, the cells isolated from the spleen and intestine of these mice were gated based on CD45+ myeloid-derived cells for further analysis of CD11b and GR1 expression using flow cytometry. Radiation significantly expanded the splenic and intestinal CD11b+ and GR1+ cell populations (Fig. 1B). Immunofluorescence staining also showed that both CD11b+ and GR1+ cells were markedly increased after radiation exposure in both the spleen and intestine (Fig. 1C). To determine whether these radiation-induced MDSCs suppressed immune responses, we co-cultured the splenic MDSCs with CFSE-labeled CD3+ T cells at different ratios in the presence of anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 1D, MDSCs significantly blocked the proliferation of CD3+ T cells at a 1:1 ratio compared to a 1:10 ratio, an essential stimulator for activation and expansion of T cells. However, T cells co-cultured with MDSCs were not significantly proliferated without stimulation by the treatment of anti-CD3/anti-CD28. To further investigate the change of MDSCs subtypes by radiation exposure, we compared the population of subtypes, which are indicated with the specific markers for granulocytic MDSCs and monocytic MDSCs. We found no significant differences between the MDSC subtypes in the spleen and intestines in the radiation-induced colitis mouse model, although MDSCs were increased by radiation (Fig. 1E).

Mice were exposed to 7.5 Gy for 1 week to induce intestinal inflammation. A Photomicrographs of colon sections, histological grades, colon lengths, body weights, and survival rates for mice 21 days after irradiation. Scale bar = 100 μm B Representative dot plots of the gating strategy used to identify CD11b+ /GR1+ cells from the spleens and intestines of mice 21 days after irradiation. C Representative immunofluorescence images of spleen and intestine stained for CD11b (green), GR1 (red), and CD11b+ /GR1+ (yellow) cells. DAPI staining (blue) was used to determine the number of nuclei. Scale bar = 100 μm D CFSE-labeled CD3+ T cells were co‑cultured with splenic MDSCs and stimulated using anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies. The cells were harvested and analyzed after 7 days. CFSE dilution demonstrated that T-cell proliferation was inhibited by MDSCs (left) and that this inhibition occurred in a dose-dependent manner (right). E The two MDSC subtypes, namely gMDSCs (CD11b+ , Ly6G+, and Ly6Clow) and mMDSCs (CD11b+ , Ly6G-, and Ly6Chigh), were identified and analyzed by flow cytometry from spleen and intestine samples. The data are represented as the mean ± SD (n = 8). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control. IR irradiation.

Depletion of mMDSCs exacerbates radiation-induced intestinal inflammation

To determine the role of each MDSC subset in radiation-induced inflammation, we treated radiation-exposed mice with anti-Ly6G or anti-Ly6C to deplete endogenous gMDSCs and mMDSCs, respectively (Fig. S2A). We confirmed that both gMDSCs and mMDSCs were reduced by these treatments (Fig. S2B). Depletion of mMDSCs using the anti-Ly6C neutralizing antibody exacerbated radiation-induced intestinal injury by increasing inflammation and weight loss (Fig. 2A). Moreover, it markedly enhanced the level of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL6 and reduced the level of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 (Fig. 2B). However, the depletion of gMDSCs by anti-Ly6G treatment resulted in no significant changes in histological grade as inflammation marker, compared to the IgG-treated group (Fig. 2A). These results suggest that the expansion of mMDSCs due to radiation exposure may have a beneficial influence on intestinal inflammatory responses in this mouse model.

Mice were tail-vein injected with either anti-IgG, anti-Ly6G, or anti-Ly6C (250 μg/mouse) four times per week after irradiation. All the results were determined 21 days after irradiation. A Photomicrographs of colon sections, histological grades, and body weights after depletion of Ly6G or Ly6C. Scale bar = 100 μm. B The relative expression of cytokines (IL10, TGFβ, IL6, IFNγ, IL1β, and TNFα) in the intestines of irradiated mice were measured by qRT-PCR. The data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 8). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. IR + IgG. IR irradiation.

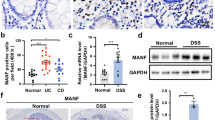

MDSCs and IL10 increase in 0.5 Gy-exposed mice

Previous studies have shown that radiation can both increase or decrease MDSCs depending on the exposure dose [23]. To determine whether the MDSC populations are changed with exposure amount, mice were exposed to 0.1, 0.5, 1, or 5 Gy levels (Fig. S3A). We found that MDSCs were increased by all radiation doses in bone marrow, spleen and the intestine 7 days after exposure (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3C). In particular, mMDSCs increased up to the 0.5-Gy exposure level, but decreased at 1 Gy and above. On the other hand, 5 Gy-exposure mice showed accumulations of gMDSCs in spleen and intestinal inflammatory responses (Fig. 3B and Fig. S3D). In addition, we showed the changes of inflammatory cytokines in the intestinal tissues of irradiated mice with 0, 0.5, and 5 Gy, of which doses induced the specific subtype of MDSCs. The expression level of IL10 (anti-inflammatory) was enhanced by radiation exposure at 0.5 Gy, but IL6, IL1β, and TNFα levels (pro-inflammatory) were only induced by the highest dose at 5 Gy (Fig. S3E). We therefore, hypothesized that the mMDSC expansion by radiation exposure at 0.5 Gy may have been attenuated by higher radiation-induced intestinal injury. To determine whether the elevated IL10 levels were derived from 0.5 Gy induced MDSCs, we isolated the spleens and intestines from radiation-exposed mice at 0.5 Gy and assessed IL10 levels. The majority of spleen and intestine IL10+ cells were CD11b+ and GR1+ , and the proportional expression was higher in mMDSCs compared with gMDSCs after 0.5 Gy exposure (Fig. 3C). Therefore, we confirmed that 0.5 Gy-induced mMDSCs (CD11b+ , Ly6G+, and Ly6Clow) expressed IL10. Furthermore, immunofluorescence staining revealed that radiation-expanded GR1+ cells expressed IL10 at higher levels than those from unexposed mice (Fig. 3D). These results demonstrated that radiation exposure 0.5 Gy enhanced CD11b+ and GR1+ MDSCs producing produced IL10. Consistent with these results, intestinal pathological conditions were not altered in response to radiation exposure 0.1 Gy and 0.5 Gy exposures compared with the unexposed mice (Fig. S3B).

Mice were exposed to either 0.5 Gy or 5 Gy total body irradiation and analyzed seven days later. Representative dot plots of the gating strategies. A The population of CD11b+ /GR1+ cells. B gMDSCs (CD11b+ , Ly6G+, and Ly6Clow) and mMDSCs (CD11b+ , Ly6G-, and Ly6Chigh) from the spleens and intestines of irradiated mice were identified and analyzed by flow cytometry. C Representative dot plots of the gating strategy used to identify IL10+ cells. IL10+ cells were gated and the proportions of CD11b+ /GR1+ cells. These cells were gated on gMDSCs (CD11b+ , Ly6G+, and Ly6Clow) and mMDSCs (CD11b+ , Ly6G−, and Ly6Chigh) cells were evaluated from mouse spleens and intestines. D Representative immunofluorescence images of cells from spleen stained for GR1 (green), IL10 (red), and GR1/IL10 (yellow). DAPI staining (blue) was used to determine the number of nuclei. Scale bar = 100 μm. The data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 8). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control.

Adoptive transfer of MDSCs ameliorates radiation-induced intestinal injury and inflammation

To determine whether radiation-expanded MDSCs altered intestinal inflammation, splenic MDSCs (induced either by radiation of 0.5 and 5 Gy) were intravenously injected into mice one and 4 days after radiation exposure for adoptive transfer (Fig. S1A). We found that transferred CSFE labeled 0.5 Gy-induced MDSCs (0.5 Gy/MDSCs) and 5 Gy-induced MDSCs (5 Gy/MDSCs) were located in the intestines (Fig. 4A). The histological analysis of intestinal sections revealed that radiation exposure promoted severe intestinal inflammation, whereas the adoptive transfer of 0.5 Gy/MDSCs alleviated intestinal inflammation and injury compared with the PBS-treated mouse group. However, the adoptive transfer of MDSCs induced by radiation exposure at 5 Gy exacerbated the intestinal inflammatory response (Fig. 4B). The results also showed that colon length, body weight, and survival were improved by the adoptive transfer of 0.5 Gy/MDSCs compared to PBS-treated mice, but the transfer of 5 Gy/MDSCs exacerbated radiation-induced damage (Fig. 4C). Therefore, the transfer of 0.5 Gy/MDSCs had a therapeutic effect of reversing intestinal inflammation. As shown in Fig. 4D, the adoptive transfer of 0.5 Gy/MDSCs reduced the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL6 and enhanced the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 in the intestines of mice after radiation exposure. These results suggest that 0.5 Gy/MDSCs expressing elevated IL10 levels may reduce radiation-induced intestinal damage.

Adoptive transfers of 0.5 Gy- or 5 Gy-induced splenic MDSCs were intravenously injected in mice on days 1 and 4 after irradiation. A Mice were injected with CFSE-labeled 0.5 Gy- or 5 Gy-induced splenic MDSCs (5 × 106 cells/100 µL) twice after irradiation. Fluorescence images of intestines were obtained 24 h after injections using an IVIS 200 image system. B Photomicrographs of colon sections and histological grades of mice 21 days after irradiation. Scale bar = 100 μm. C Photomicrograph of colons and measurements of colon length, survival rates, and body weights in mice 21 days after irradiation. D The relative expression of cytokines (IL10, TGF β, IL6, IFNγ, IL1β, and TNFα) in the intestines of irradiated mice were measured using qRT-PCR. The data are represented as the mean ± SD (n = 8). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. PBS. IR irradiation.

MDSCs reduce radiation-induced intestinal damage in vivo by activating IL10 and SOCS3

Both IL6 and IL10 have been shown to induce STAT3 activation in a variety of cellular responses [24]. In addition, Hovsepian et al. showed that activated IL10 promoted STAT3 phosphorylation and enhanced the expression of SOCS3, which prevented an inflammatory response [25]. We therefore, explored whether the adoptive transfer of 0.5 Gy/MDSCs could enhance STAT3 and SOCS3 expression in recipient mice. Western blot analysis of intestinal samples from recipient mice showed that STAT3 phosphorylation was elevated 7 days after treatment with 0.5 Gy/MDSCs (Fig. 5A), and the levels of both SOCS3 and IL10 were increased 21 days after treatment, whereas IL6 expression was inhibited. In addition, immunofluorescence staining of IL6 and SOCS3 in spleens of radiation-exposed recipient mice showed that 0.5 Gy/MDSCs significantly reduced IL6 expression but enhanced SOCS3 expression (Fig. 5B). Compared to radiation exposure alone, the adoptive transfer of 0.5 Gy/MDSCs increased the activation of both phosphorylated STAT3 and SOCS3 in the intestines of radiation-exposed recipient mice (Fig. 5C). We also found that treatment with 0.5 Gy/MDSCs increased the expression of SOCS3 and IL10 in the intestines of recipient mice when compared to the intestines of mice exposed to radiation alone (Fig. 5D). IL10 is an important cytokine in the immune regulation that mediates its effects via a transmembrane IL10 receptor (IL10R). To reveal whether 0.5 Gy/MDSC could induce the level of the specific receptor for IL10, we examined it in the intestinal tissue of recipient mice with 0.5 Gy/MDSC (Fig. S4). The expression of IL10R was not changed by the radiation exposure and 0.5 Gy/MDSC, compared to control. We concluded that IL10 secreted by MDSC could directly activate the STAT3/SOCS3 signal pathway in the intestinal epithelial cells without fluctuation of IL10 receptor expression.

A Colon tissue was collected from IR-exposed mice at the indicated time points. The expression patterns of p-STAT3, STAT3, SOCS3, IL10, and IL6 in the intestines of adoptive-transfer mice (0.5 Gy/MDSCs) were confirmed by western-blot analysis. β-actin was used as a loading control. The data are represented as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. day 0. B Representative immunofluorescence images of spleen stained for IL6 (green), SOCS3 (red). Scale bar = 100 μm. C Spleen was stained for p-STAT3 (green), SOCS3 (red) and p-STAT3 and SOCS3 (yellow) cells. DAPI staining (blue) was used to determine the number of nuclei. Scale bar = 100 μm. D The levels of SOCS3 and IL10 in the intestine were evaluated using immunohistochemistry. The quantitative analyses of labeled cells in the intestines were performed by randomly selecting different regions from three separate slides using Zeiss Zen 2009 software. Scale bar = 100 μm. The data are represented as the mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 vs. control. IR irradiation.

MDSC-secreted IL10 enhances STAT3/SOCS3 signaling in vitro

To investigate the possibility that increased IL10 directly stimulates STAT3 and SOCS3, we treated recombinant IL10 protein to CCD841 and IEC-6 cells. This IL10 treatment resulted in activation of both phosphorylated STAT3 and SOCS3 protein levels (Fig. 6A). Next, to explore the mechanisms for the intestinal-damage protection of MDSC after radiation exposure, we directly co-cultured IEC-6 cells with either splenic 0.5 Gy/MDSCs or 5 Gy/MDSCs after radiation exposure. As shown in Fig. 6B, the level of phosphorylated STAT3 in IEC-6 cells was increased by radiation alone and after co-culture with both MDSC types. Co-culturing with 0.5 Gy/MDSCs promoted the expression of both SOCS3 and IL10 compared to radiation exposure treatment alone, whereas co-culturing with 5 Gy/MDSCs did not result in changes to the expression of these proteins in IEC-6 cells. In addition, we found that the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL6 was suppressed by co-culturing with 0.5 Gy/MDSCs. To determine whether the elevation of IL10 caused by 0.5 Gy/MDSC plays an important role for inhibiting inflammation, 0.5 Gy/MDSCs were co-cultured with radiation-exposed IEC-6 cells using a transwell system. As expected, 0.5 Gy/MDSCs significantly reduced IL6 levels and upregulated both SOCS3 and IL10 expression in IEC-6 cells (Fig. 6C). These data indicated the secreted IL10 from 0.5 Gy/MDSC stimulated the activation of SOCS3 signaling, and consequently increased the expression of IL10 in IEC-6 cells. We therefore hypothesized that increased IL10 expression in 0.5 Gy/MDSCs could suppress radiation-induced damage by enhancing SOCS3 expression. To evaluate the protective effect of SOCS3 in the radiation-induced inflammatory response, we depleted SOCS3 using a siRNA approach in IEC-6 cells. Under co-culture conditions, 0.5 Gy/MDSCs did not alter the expression of IL6 and IL10 in SOCS3 knockdown cells (Fig. 6D). Moreover, the treatment of recombinant IL10, mimicking the secretion of 0.5 Gy/MDSCs could not suppress the IL6 expression in SOCS3-depleted IEC-6 cells (Fig. 6E and F). These results indicate that 0.5 Gy/MDSCs suppressed radiation-induced intestinal inflammation through the upregulation of IL10 and SOCS3 expression.

A Western blot analyses were used to determine the expression patterns of IL10-stimulated p-STAT3 and SOCS3 protein levels in CCD841 and IEC-6 cells. B, C Western-blot analysis was used to determine the expression of p-STAT3, STAT3, SOCS3, IL10, and IL6 in co-cultured IEC-6 cells with 0.5 Gy/MDSCs or 5 Gy/MDSCs directly or indirectly using a transwell system. D The expression of p-STAT3, SOCS3, IL10, and IL6 in IEC-6 cells depleted of SOCS3 using siRNA and co-cultured with splenic 0.5 Gy/MDSCs after IR exposure were determined using western blot analysis. E The expression of p-STAT3, SOCS3, IL10, and IL6 in IEC-6 cells depleted of SOCS3 using siRNA and co-cultured with recombinant IL10 after IR exposure were determined using western blot analysis. F Representative immunofluorescence images of spleen cells stained for phosphorylated STAT3 (green), IL6 (red), and both p-STAT3 and IL6 (yellow). DAPI staining (blue) was used to determine the number of nuclei. Scale bar = 100 μm. IR irradiation.

Discussion

Radiation-induced colitis is an insidious and clinically important sequel to radiotherapy for abdominal and pelvic malignancies [26]. It can result in dysplasia-based radiation-associated colon cancer, which tends to be diagnosed at an advanced stage and to have a dismal prognosis [27]. Using a mouse model, we have demonstrated that radiation-induced mMDSCs substantially ameliorates colon inflammation through the production of IL10 and activation of the STAT3/SOCS3 signaling pathway. To our knowledge, this is the first experimental evidence indicating that mMDSCs have an immunoregulatory function in a model of radiation-induced colitis.

We firstly focused on the changes of MDSDs at the site of inflamed lesions such as the spleen and intestine, where inflammatory cytokines are increasingly secreted and MDSCs are recruited in pathological conditions such as chronic infection, inflammation, and cancer. IMCs generated in bone marrow quickly differentiate into different peripheral organs. Therefore, we also examined the level of MDSCs in bone marrow, but could not observe the different data from those of the spleen and intestines (Fig. S1C). We found that radiation exposure caused intestinal inflammation accompanying with changes in several inflammatory parameters, including increased proliferation of epithelial cells, a decrease of villus length and an increase of crypt depth, and extension of muscularis and submucosa in the intestine (Figs. 1A, 2A and 4B). The morphological changes in the inflammatory intestinal tissue were caused by the radiation-induced changes of intestinal epithelial cells, including enlargement and lengthening of the cell body, and protruding around the cells (Fig. S5). Moreover, MDSCs levels were increased by radiation exposure together with increased inflammation in the intestinal tissue, which is in accordance with the expression of several inflammatory cytokines (Fig. S3). Cytokines fluctuation in the intestinal epithelial cells responding to radiation exposure contributed to the histological changes, clearly indicating that that the inflammation of the intestine was aggravated with the radiation exposure over 1 Gy (Fig. S3E).

We found that mMDSC depletion using anti-Ly6C treatment exacerbated radiation-induced inflammation, increased pro-inflammatory cytokines, and decreased anti-inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 2B). This supports previous findings that mMDSC-derived IL10 enhanced immunosuppressive activity by inhibiting CD4+ T-cell proliferation [28]. The findings related to injecting IL10-overexpressing MDSCs into mice with radiation colitis support the hypothesis that these MDSCs may decrease intestinal injury and inflammation through STAT3 and SOCS3 signaling (Figs. 5 and 6). Such intestinal-damage recovery may have been stimulated by anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL10 and TGFβ, after the adoptive transfer of 0.5 Gy/MDSCs. The clinical significance of MDSC subtypes in different pathological processes related to intestinal inflammation has been previously reported, including inflammatory bowel diseases, colon inflammatory mucosa, and tumors [29, 30]. The present data suggest that mMDSC accumulation in radiation-damaged sites relieves immunosuppressive inflammatory stress through the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines.

Interestingly, MDSC-subtype levels were different in mice exposed to different doses of radiation, from 0.1 to 5 Gy (Fig. S3). It is not easy to differentiate the physiological response of radiation caused by radiation exposure itself from the radiation-induced inflammation, including subpopulation expansion of MDSDs expansion. However, based on our results, it can be interpreted as a specific response of radiation itself, rather than expansion of MDSC caused by radiation-induced inflammation. As shown in Supplementary Figs. S3D and S3E, particularly, radiation exposure at 0.1 Gy and 0.5 Gy increased mMDSC, which contains high level of IL10 and TGFβ. Exposure with 1 Gy and 5 Gy showed that increased gMDSC accompanied with elevated IL6 and IL1β expression. We also found that high doses of radiation of 1 Gy and 5 Gy induced pathophysiology inflammatory response in the intestine, whereas lower doses of radiation of 0.1 Gy and 0.5 Gy could not affect inflammatory phenotype changes (Fig. S3B). In other words, although the mMDSC population was increased by radiation exposure at 0.5 Gy, inflammation was not observed as shown in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and histological inflammation. Therefore, we concluded that the change of MDSCs subpopulation could be governed by the different mechanisms depending on the dose of radiation exposure, and we proposed that MDSCs expansion could be driven by the radiation exposure itself, not by radiation-induced inflammation.

Similar to other studies, these findings demonstrate that physiological responses to radiation, particularly immune responses, may vary depending on dosage exposure [31]. Detrimental effects of high dose radiation, usually over 0.5 Gy are well known to induce the much of cell deaths leading to tissue damage through several pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL6, IL1β, TNFα, etc.) and consequently, the malfunction of organs. However, lower level of radiation <0.5 Gy showed various physiological effects, including increase longevity, activation of immunity, and adaptive response to stress [32, 33]. Understanding of health effects of low dose radiation, especially <100 mSv, is still incomplete and difficult. Our finding of the 0.5 Gy/MDSCs with anti-inflammatory function could be one of key data to reveal the unknown physiology of beneficial effects of radiation at low doses.

Selective depletion or adaptive transfer of monocytic MDSC (mMDSC) or granulocytic MDSC (gMDSC) are being investigated as a potential therapeutic strategy to modulate MDSCs from the pathology condition [34]. Ingunn M et al. suggested that targeted depletion of a single myeloid subset, the gMDSC, can unmask an endogenous T cell response, revealing an unexpected latent immunity and invoking targeting of gMDSC as a potential strategy to exploit for treating this highly lethal disease [35]. It is suggested that radiation-induced subtypes of MDSCs cannot be directly controlled, but can be modulated through depletion or adaptive transfer of subtype MDSC. Developing strategies to target the plastic and interrelated myeloid cell lineages should take into account the potential for homeostatic regulation between distinct MDSC subsets. After the adoptive transfer of 0.5 Gy/MDSCs to mice, high levels of phosphorylated STAT3 and SOCS3 were found, IL10 expression was significantly increased, and colitis symptoms were alleviated (Figs. 4 and 5). The SOCS families of gene products are cytoplasmic molecules that regulate cytokine signaling [36], bidirectionally decreasing IL6 expression and increasing IL10 expression [24]. Decreased IL6 by treatment with IL10 in the radiation exposure IEC-6 cells was recovered when SOCS3 was depleted (Fig. 6E). These results showed that SOCS3 plays an important anti-inflammatory role through inhibition of radiation-induced IL6 in colitis. These findings, taken together with our in vitro results of co-cultured IEC-6 cells with 0.5 Gy/MDSCs (Fig. 6B and C), suggest that the mMDSC-activated STAT3 signaling pathway inhibits radiation-induced intestinal damage via SOCS3-mediated modulation of inflammatory cytokines. Intestinal epithelial cells occupy a prominent place within the complex and dynamic system of the intestinal barrier, highlighting their role in pathogenesis [37]. We first focused on human or mouse-derived intestinal epithelial cell lines, which are the pathological conditions cause of colitis. Furthermore, we found that treatment of 0.5 Gy/MDSCs in mouse-derived endothelial cells (C166) promoted the expression of both SOCS3 and IL10 compared to the control group without 0.5 Gy/MDSC treatment, whereas it suppressed the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine IL6 (Fig. S6). In other words, the etiological factors of colitis are not only epithelial barrier damage and inflammatory response, but also dysfunction of the endothelium as mentioned in previous papers [37].

Conventional anti-inflammatory drugs use is somewhat limited to cure of IR-induced colitis. Steroids treatment for many years as the traditional anti-inflammatory treatment for colitis is at risk for adverse drug reactions and complications, including reduced glucose tolerance, reduced bone density, cataract, and progression of atherosclerosis [38]. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the most commonly used medications for the treatment of various inflammations, could induce the development of gastrointestinal toxicity such as mucosal injury in the form of erosions and ulcers, small bowel bleeding [39]. Thus, we thought that cell therapy using MDSCs could be one of the potential therapeutic approaches for overcoming IR-induced colitis [26]. Treatment of MDSCs may suppress the toxicity of conventional anti-inflammatory drugs, which could enhance the treatment efficiency of colitis. Further studies should be performed to examine whether the targeting of MDSCs could be applied as a better strategy than traditional anti-inflammatory therapy in the era of immunotherapy.

Therefore, our findings that 0.5 Gy-induced MDSCs play an important immunoregulatory role in the colitis mouse model could be consolidated with further clinical experiments using the patients suffering from the colitis. Some previous studies reported that the increased human MDSCs with the suppressive function was observed in peripheral blood from patients with inflammatory bowel disease [6] and patients with ulcerative colitis [10]. These results propose that our in-vivo experimental data could be confirmed in the clinical cases if appropriate design and implementation of experiment are followed, including the measurement of MDSCs level and cytokines, identifying the subtypes and characterizing the function of MDSCs from the patients’ peripheral blood. However, we should carefully consider the function of cytokines regulating the MDSCs in the therapeutic strategy on radiation-induced colitis. Some studies have shown that the pathological mechanisms of colitis driving mucosal inflammation are likely to differ between patients depending on the effective cytokines, which would explain why the targeting of a single inflammatory cytokine is not effective in many cases [28]. Moreover, Mohammed et al. reported the example of a double-edged sword role of IL-10 in colitis-associated colorectal cancer. In contrast to IL-10 which acts as an inhibitor of colitis, higher levels of IL-10 in the colon lamina propria activate the STAT3 pathway promoting tumor growth in the colitis-associated colorectal cancer [40].

In light of this, the application of 0.5 Gy/MDSC in the colitis model is a potent anti-inflammatory strategy, but the risk of tumorigenesis cannot be excluded. Therefore, further studies for the therapeutic approach of MDSCs secreting IL10 using the model mice with colorectal cancer and some colitis patients should be performed continuously.

Materials and methods

Animal models and radiation exposure

C57BL/6 mice (male, 7-week old) were obtained from Orient Bio Inc. (Seongnam, Korea) and were housed in a temperature-controlled room under 12-h light/dark cycles. Food and water were provided ad libitum under specific pathogen-free conditions at the animal facility of the Korea Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences. After the adaptation period, all animals were randomly grouped (n = 8). The selection of sample sizes for clinically significant differences between groups was based on previously published studies [41, 42]. To establish our intestinal inflammation model, mice received a total of three 2.5 Gy doses (one dose every other day) for a total dose of 7.5 Gy. To determine whether the expansion of MDSCs by radiation altered intestinal inflammation, mice were tail vein-injected with either 0.5 Gy- or 5 Gy-induced MDSCs twice (days 1 and 4) after irradiation (Fig. S1A). To determine whether the expansion of MDSCs by radiation altered intestinal inflammation, mice were tail vein-injected with either 0.5 Gy- or 5 Gy-induced MDSCs twice (days 1 and 4) after irradiation (Fig. S1A). To determine the roles of specific MDSC subsets during radiation-induced inflammation, C57BL/6 mice were tail-vein injected with antibodies against either IgG, Ly6G, or Ly6C (250 μg/mouse) once per week for four weeks after 7.5 Gy irradiation (as described above). All animal experiments were independently implemented depending on each purpose, following the guideline of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All tested animals are included to interpret the data. Results were determined beginning 21 days after irradiation. Body weights were measured every 3 days. A schematic diagram of the experimental design is shown in Fig. S2A. To determine whether MDSC populations changed with radiation dosing, mice were irradiated using a single 0.1, 0.5, 1, or 5 Gy whole-body dose in an X-RAD 320 X-ray irradiator (Precision X-RAY, Softex, CT, USA). The spleens and intestinal tissues were harvested from these mice 7 days after irradiation, and the MDSC populations and histological lesions were analyzed (Fig. S3).

Histological analysis and scoring

Mouse colon samples were fixed using 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin wax, and sectioned (4 μm) transversely. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Grading scores (0–4 for each) were based on both observed inflammation and observed epithelial injury. The observed inflammation scores were defined as follows: 0, no inflammation; 1, low level of inflammation with mildly increased inflammatory cells in the lamina propria; 2, moderately increased inflammation in the lamina propria (multiple foci); 3, a high level of inflammation with evidence of wall thickening by inflammation; and 4, severe inflammation with transmural leukocyte infiltration and/or architectural distortion [14, 43]. Image from each group was evaluated randomly selecting different locations in each group. The histological grade was blindly determined by two observers and the discrepancy between evaluations was resolved after a joint review using a multi-head microscope.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence staining

Immunohistochemical analyses were performed to evaluate SOCS3, IL10, and IL10 receptor expression levels in the intestine. Tissues were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated with ethanol, and cleared with xylene. Microscopy images of the tissue were analyzed for the specific 3,3′-diaminobenzidine signals. For immunofluorescence staining, spleen and intestinal samples from each mouse were embedded in OCT solution (Tissue-Tek, Sakura Finetek, USA) and then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue cryosections (10 μm) on slides were washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and incubated in blocking solution (1× PBS with 5% bovine serum albumin) for 1 h at room temperature. The tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies against CD11b (CST, 17800, 1:100 dilution, IL6 (CST, 12912, 1:100 dilution), IL10 (Abcam, ab192271, 1:100 dilution), and SOCS3 (Abcam, ab16030, 1:100 dilution), phospho-STAT3 (CST, 9145, 1:100 dilution), and GR1 (R&D Systems, MN, USA, MAB1037-100, 1:100 dilution) overnight at 4 °C. For detection of primary-antibody binding, the tissue sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488- or Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-rat or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) for 2 h at room temperature. All primary antibodies were diluted 1:100, and the second antibodies were diluted to 1:200, in blocking solution. Nuclei were counterstained using DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). Images of the fluorescent signals were examined using a scanning confocal laser microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and quantified using ImageJ analysis software.

Cell-surface marker staining for flow cytometry

Intestinal and splenic samples were collected to measure any changes in MDSC populations. The tissues were homogenized gently in RPMI 1640 medium containing 3% FBS using the plunger of a 2-mL syringe and passed through a 40-μm cell strainer. The suspension was subjected to centrifugation at 300 × g for 10 min and the supernatant was discarded. The resulting cell pellets were resuspended in flow-cytometry stain buffer. For staining, 200-μL samples were incubated for 20 min in the dark at 4 °C with antibodies against cell type-specific markers. All events were first gated on CD45 signaling to identify hematopoietic cells, and then were gated on CD11b signaling to identify myeloid cells. The events were further sub-gated based on granulocytic MDSCs (gMDSCs; CD11b+ , Ly6G+, and Ly6Clow) and monocytic MDSCs (mMDSCs; CD11b+ , Ly6G–, and Ly6Chigh). The populations of lymphocytes (CD45 + and CD3+ ) and IL10+ in splenocytes or intestine were also analyzed. All antibodies (CD45; Cat.147708, CD11b; Cat.101206, Ly6G; Cat.127608, Ly6C; Cat. 128018, CD3; Cat.100204, IL10; Cat. 505008) for flow cytometric analysis were purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Each experiment was analyzed using a BD FACSCanto II Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and FlowJo v7.6.5 software.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the mouse intestine using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA synthesis was performed using oligo-dT primers and a RevertAid Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The resulting cDNA was then subjected to PCR amplification using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) and gene-specific primers for the various inflammatory cytokines (Table S1). The primers for IL10, TGFβ, IL6, IFNγ, IL1β, and TNFα were designed from their sequences. Amplifications were performed using an activation step at 95 °C for 10 s, followed by 30 s of denaturation at 98 °C, and 8 s of annealing at 60.5 °C for 35 cycles. GAPDH transcript levels in each sample were used to normalize the results, and the fold-changes in mRNA levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with the values expressed relative to the non-irradiated group values.

T-cell and MDSC isolation

For MDSC and T-cell isolations, individual spleens were homogenized in 10 mL RPMI 1640 complete medium to release splenocytes. Splenocyte mixtures were then passed through 40-μm cell strainers to obtain single-cell suspensions. CD3+ T cells were isolated by positive selection using magnetic cell sorting (Pan T Cell Isolation Kit II, Miltenyl), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. MDSC isolation was performed using total splenocytes from either non-irradiated or irradiated mice according to the protocol for the Myeloid-derived Suppressor Cell Isolation Kit (MACS Mitenyl Biotec). GR1 high cells from naïve mice were used for the T-cell suppression assays, and GR1 high cells isolated from irradiated mice dosed with 0.5 Gy (0.5 Gy/MDSC) or 5 Gy (5 Gy/MDSC) were used for the adoptive transfer experiments and the in vitro treatment experiments (Table 1).

Proliferation assay for T cells and MDSCs

Isolated T cells (1.5 × 106 cells/μL) were stained with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl esther (CFSE) and co-cultured with splenic MDSCs from naïve mice at T-cell:MDSC ratios of 0:1, 1:1, 5:1 and 10:1 in RPMI-1640 medium and stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). T cells were seeded into 96-well plates (Costar, Lowell, MA, USA) either in the presence or absence of MDSCs, as indicated above. After 7 days of culture, the cells were harvested. As CFSE signaling was reduced with each cell division, cells exhibiting low CFSE fluorescence intensity were considered to have proliferated.

Adoptive transfer

CFSE-labeled splenic 0.5 Gy/MDSCs or 5 Gy/MDSCs (200 μL/mouse, 4 × 106 cells) were tail-vein injected into mice with radiation-induced colitis on days 1 and 4 after irradiation. Fluorescence imaging of colons was performed 24 h after these MDSC injections using an IVIS 200 imaging system (535-nm excitation filter, 600-nm emission filter).

Cell culture and siRNA transfection

The normal human colon epithelial cell line CCD841 (CRL-1790), the rat small intestinal epithelial cell line IEC-6 (CRL-1592), and mouse-derived endothelial cell line C166 (CRL-2581) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). All cell lines were examined by mycoplasma contamination with MycoSEQ™ Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Cells were maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 0.1 U/mL recombinant human insulin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. CCD841 or IEC-6 cells were seeded in six-well culture dishes, and 1 × 106 cells/well were stimulated with IL10 (50 or 100 ng/mL) for 24 h and analyzed for protein levels of STAT3, phosphorylated STAT3, and SOCS3. Briefly, 0.5 Gy radiation-induced MDSCs were described as 0.5 Gy/MDSCs, and 5 Gy radiation-induced MDSCs were described as 5 Gy/MDSCs. IEC-6 cells and C166 cells were either directly co-cultured or indirectly co-cultured (using a transwell system) with splenic 0.5 Gy/MDSCs or 5 Gy/MDSCs (3 × 105 cells/μL) after radiation exposure. For SOCS3 mRNA silencing, SOCS3 siRNA was transfected into IEC-6 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. IEC-6 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well into six-well dishes and cultured overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2 until the cells reached 70% confluency. The transfected cells were then incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 24 h with SOCS3 siRNA. Transfected IEC-6 cells were then treated with either splenic 0.5 Gy/MDSCs or non-irradiated MDSCs. In addition, recombinant IL10 (100 ng/mL) was treated to SOCS3-depleted IEC-6 cells, mimicking the secretion of 0.5 Gy/MDSCs. Analyses of changes in SOCS3 protein by SOCS3 mRNA silencing were determined using western blots.

Western blot

Cells or tissues were lysed in lysis buffer (Cell signaling Technology, MA, USA) containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 1 μg/mL leupeptin supplemented with both a proteinase-inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). Lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. After probing with primary antibodies, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, and visualized using Pierce ECL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). We used antibodies to IL10 (CST, 12136 or Abcam, ab192271, 1:1000 dilution), SOCS3 (CST, 52113, 1:1000 dilution), IL6 (CST, 12912 or CST, 12153, 1:1000 dilution), STAT3 (CST, 30835, 1:1000 dilution), and phosphorylated STAT3 (CST, 9145, 1:1000 dilution). β-actin (SC-47778, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) was used as the loading control.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments with three replicates each. The variation is similar for groups that are being statistically compared. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 software. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant using Student’s t-test or a one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons. The variation is similar for groups that are being statistically compared.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

25 February 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-04643-w

29 September 2022

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-05295-6

References

Holley AK, Miao L, St Clair DK, St Clair WH. Redox-modulated phenomena and radiation therapy: the central role of superoxide dismutases. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1567–89.

Stacey R, Green JT. Radiation-induced small bowel disease: latest developments and clinical guidance. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2014;5:15–29.

Theis VS, Sripadam R, Ramani V, Lal S. Chronic radiation enteritis. Clin Oncol. 2010;22:70–83.

Webb GJ, Brooke R, De Silva AN. Chronic radiation enteritis and malnutrition. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:350–7.

Wang Y, Ding Y, Deng Y, Zheng Y, Wang S. Role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the promotion and immunotherapy of colitis-associated cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e000609.

Haile LA, von Wasielewski R, Gamrekelashvili J, Krüger C, Bachmann O, Westendorf AM, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in inflammatory bowel disease: a new immunoregulatory pathway. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:871–81.

Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–74.

Bergenfelz C, Leandersson K. The generation and identity of human myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Front Oncol. 2020;10:109.

Ma P, Beatty PL, McKolanis J, Brand R, Schoen RE, Finn OJ. Circulating myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSC) that accumulate in premalignancy share phenotypic and functional characteristics with MDSC in cancer. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1401.

Greten TF, Manns MP, Korangy F. Myeloid derived suppressor cells in human diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:802–7.

Dorhoi A, Du Plessis N. Monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in chronic infections. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1895.

Kustermann M, Klingspor M, Huber-Lang M, Debatin KM, Strauss G. Immunostimulatory functions of adoptively transferred MDSCs in experimental blunt chest trauma. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7992.

Zhou L, Miao K, Yin B, Li H, Fan J, Zhu Y, et al. Cardioprotective role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in heart failure. Circulation. 2018;138:181–97.

Lee CR, Kwak Y, Yang T, Han JH, Park SH, Ye MB, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells are controlled by regulatory T cells via TGF-beta during murine colitis. Cell Rep. 2016;17:3219–32.

Wu L, Du H, Li Y, Qu P, Yan C. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3C) promotes myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion and immune suppression during lung tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2131–41.

Rebe C, Vegran F, Berger H, Ghiringhelli F. STAT3 activation: A key factor in tumor immunoescape. JAKSTAT. 2013;2:e23010.

Sims NA. The JAK1/STAT3/SOCS3 axis in bone development, physiology, and pathology. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:1185–97.

Zundler S, Neurath MF. Integrating immunologic signaling networks: the JAK/STAT pathway in colitis and colitis-associated cancer. Vaccines. 2016;4:5.

Fu XY. STAT3 in immune responses and inflammatory bowel diseases. Cell Res. 2006;16:214–9.

Chaves de Souza JA, Nogueira AV, Chaves de Souza PP, Kim YJ, Silva Lobo C, Pimentel Lopes de Oliveira GJ, et al. SOCS3 expression correlates with severity of inflammation, expression of proinflammatory cytokines, and activation of STAT3 and p38 MAPK in LPS-induced inflammation in vivo. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:650812.

Westbrook AM, Szakmary A, Schiestl RH. Mechanisms of intestinal inflammation and development of associated cancers: lessons learned from mouse models. Mutat Res. 2010;705:40–59.

Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking inflammation and cancer. J Immunol. 2009;182:4499–506.

Kang C, Jeong SY, Song SY, Choi EK. The emerging role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol J. 2020;38:1–10.

Niemand C, Nimmesgern A, Haan S, Fischer P, Schaper F, Rossaint R, et al. Activation of STAT3 by IL-6 and IL-10 in primary human macrophages is differentially modulated by suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. J Immunol. 2003;170:3263–72.

Hovsepian E, Penas F, Siffo S, Mirkin GA, Goren NB. IL-10 inhibits the NF-kappaB and ERK/MAPK-mediated production of pro-inflammatory mediators by up-regulation of SOCS-3 in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected cardiomyocytes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e79445.

Kountouras J, Zavos C. Recent advances in the management of radiation colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:7289–301.

Tamai O, Nozato E, Miyazato H, Isa T, Hiroyasu S, Shiraishi M, et al. Radiation-associated rectal cancer: report of four cases. Dig Surg. 1999;16:238–43.

Park MJ, Lee SH, Kim EK, Lee EJ, Baek JA, Park SH, et al. Interleukin-10 produced by myeloid-derived suppressor cells is critical for the induction of Tregs and attenuation of rheumatoid inflammation in mice. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3753.

Katoh H, Wang D, Daikoku T, Sun H, Dey SK, Dubois RN. CXCR2-expressing myeloid-derived suppressor cells are essential to promote colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:631–44.

Xi Q, Li Y, Dai J, Chen W. High frequency of mononuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells is associated with exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease. Immunol Invest. 2015;44:279–87.

Carvalho HA, Villar RC. Radiotherapy and immune response: the systemic effects of a local treatment. Clin (Sao Paulo). 2018;73:e557s.

Cuttler JM, Feinendegen LE, Socol Y. Evidence that lifelong low dose rates of ionizing radiation increase lifespan in long- and short-lived dogs. Dose Response. 2017;15:1559325817692903.

Liu X, Liu Z, Wang D, Han Y, Hu S, Xie Y, et al. Effects of low dose radiation on immune cells subsets and cytokines in mice. Toxicol Res. 2020;9:249–62.

Law AMK, Valdes-Mora F, Gallego-Ortega D. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as a therapeutic target for cancer. Cells. 2020;9:561.

Stromnes IM, Brockenbrough JS, Izeradjene K, Carlson MA, Cuevas C, Simmons RM, et al. Targeted depletion of an MDSC subset unmasks pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma to adaptive immunity. Gut. 2014;63:1769–81.

Ding Y, Chen D, Tarcsafalvi A, Su R, Qin L, Bromberg JS. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 inhibits IL-10-mediated immune responses. J Immunol. 2003;170:1383–91.

Cibor D, Domagala-Rodacka R, Rodacki T, Jurczyszyn A, Mach T, Owczarek D. Endothelial dysfunction in inflammatory bowel diseases: Pathogenesis, assessment and implications. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1067–77.

Okayasu M, Ogata H, Yoshiyama Y. Use of corticosteroids for remission induction therapy in patients with new-onset ulcerative colitis in real-world settings. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019;7:1565889.

Shin SJ, Noh CK, Lim SG, Lee KM, Lee KJ. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced enteropathy. Intest Res. 2017;15:446–55.

Ibrahim ML, Klement JD, Lu C, Redd PS, Xiao W, Yang D, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells produce IL-10 to elicit DNMT3b-dependent IRF8 silencing to promote colitis-associated colon tumorigenesis. Cell Rep. 2018;25:3036–46.e3036.

Oh SY, Cho KA, Kang JL, Kim KH, Woo SY. Comparison of experimental mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:333–40.

Zhu F, Li H, Liu Y, Tan C, Liu X, Fan H, et al. miR-155 antagomir protect against DSS-induced colitis in mice through regulating Th17/Treg cell balance by Jarid2/Wnt/beta-catenin. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;126:109909.

Villanacci V, Antonelli E, Geboes K, Casella G, Bassotti G. Histological healing in inflammatory bowel disease: a still unfulfilled promise. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:968–78.

Funding

This study was supported by the 50535-2021 grant from the Nuclear Safety and Security Commission (NSSC), Republic of Korea, and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea government (MSIT), grant number (No. NRF2019R1F1A105994013). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, and preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors have approved their authorship in this work and contributed as follows: YY and AK implemented most experiments of data analysis and draft writing, final approval of the version to be published. HJ contributed to the animal experiments and acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data. KM and SS aided drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. AK is responsible for the design of the experiments, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Korea Institute of Radiological & Medical Science Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)-approved protocol (Kirams2019-0013).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Edited by Hans-Uwe Simon

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-05295-6

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, Y.Y., Seong, K.M., Lee, H.J. et al. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Expansion of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells ameliorated intestinal inflammatory response by radiation through SOCS3 expression. Cell Death Dis 12, 826 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-04103-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-04103-x