Abstract

Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) have garnered attention for their potential in cancer therapy due to their ability to home to tumor sites. Engineered MSCs have been developed to deliver therapeutic proteins, microRNAs, prodrugs, chemotherapy drugs, and oncolytic viruses directly to the tumor microenvironment, with the goal of enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects. Despite promising results in preclinical studies and clinical trials, challenges such as variability in delivery efficiency and safety concerns persist. Ongoing research aims to optimize MSC-based cancer eradication and immunotherapy, enhancing their specificity and efficacy in cancer treatment. This review focuses on advancements in engineering MSCs for tumor-targeted therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Facts

-

MSCs possess tumor-homing abilities and exhibit low immunogenicity.

-

MSCs can be engineered to deliver therapeutic agents, such as proteins, microRNAs, and drugs, directly to the tumor microenvironment.

-

Significant advancements have been made in engineering MSCs to enhance their efficacy in cancer treatment.

Open Questions

-

How can the targeting efficiency and therapeutic delivery of MSCs be further optimized?

-

What are the long-term safety and efficacy profiles of engineered MSCs in clinical settings?

-

How do MSC-based therapies compare with other emerging treatments, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T cell therapy, particularly regarding cost-effectiveness, patient outcomes, and long-term benefits?

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) were first discovered in the bone marrow stroma in 1967 and identified as “colony-forming unit fibroblasts” [1]. Subsequently, it has been found that MSCs are distributed throughout nearly all types of tissue [2], including, but not limited to, the umbilical cord (UC) [3], adipose tissue (AD) [4, 5], and dental pulp (DP) [6]. As one of the most widespread cell types in the human body, MSCs exhibit an exceptional capacity to differentiate into multiple mesenchymal cell lineages, such as adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes [7, 8]. MSCs have elicited considerable interest due to their immune privilege, specifically low immunogenicity (absence of MHC-I expression and nearly negligible expression of MHC-II on the surface) [9].

Quality control standardization of MSC treatment may accelerate the advancement of MSC clinical applications. Since 2006, the International Society for Cell and Gene Therapy and the MSC Scientific Committee have promoted the standardization of MSC therapy in both preclinical researches and human translational studies [10,11,12]. The quality control explicitly defines the identification, purity, potency, proliferative capacity, genomic stability, and microbiological testing of MSCs. By the end of 2023, over 1000 MSC-based clinical trials were registered with clinicaltrials.gov to confirm the feasibility and effectiveness of MSC therapies for various diseases. MSCs have been successfully applied to treat inflammatory diseases and organ injuries, such as graft versus host disease and systemic lupus erythematosus [13, 14], due to their ability to migrate to sites of tissue injury and participate in repair [15]. And there have been no explicit records of significant donor rejection in several clinical trials for treatment [16]. Similarly characterized by chronic inflammation, tumors can be considered “wounds that never heal” [17]. MSCs are continuously recruited to tumors and become crucial components of the tumor microenvironment [18, 19].

Bioengineering methods, as a powerful approach to enhance the efficacy of MSCs, can expand the applications of MSC treatment, particularly in anti-cancer therapeutics. MSCs have been modified to deliver interferons, interleukins, anti-angiogenic agents, pro-apoptotic proteins, pro-drugs, or oncolytic viruses, to directly induce tumor apoptosis or activate immune cells to combat tumors [20,21,22]. Here, we summarize the mechanisms by which naïve MSCs are involved in tumor progression, as well as the applications and challenges of engineered MSCs in tumor treatment.

MSCs as Trojan Horses

The tumor microenvironment generates an immunosuppressive niche, characterized by overrepresentation of immunosuppressive immune cells, continuous tissue remodeling, and a diverse array of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors [23]. The anti-inflammatory immune state in the tumor microenvironment compromises healing processes [24]. A hallmark of all solid tumors is their heightened metabolic activity coupled with an inadequate oxygen supply [25]. During tumor progression, MSCs are mobilized and recruited to the tumor site and become tumor-associated MSCs in response to signals from growing tumors, thereby orchestrating the local immune microenvironment.

In 1955, Thomlinson and Gray proposed the concept of tumor hypoxia after examining histological sections of human epithelial tumors [26]. To this day, this concept has been repeatedly confirmed by scientists, who have reached a consensus that a hypoxic microenvironment is a common feature of most solid tumors [27, 28]. As transcription factors directly responding to the hypoxic environment, hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) are involved in fundamental cellular processes that promote tumor cell survival in the hostile hypoxic tumor microenvironment, such as glucose metabolism and angiogenesis. Thus, chaotic angiogenesis pathways and blood flow variations significantly hinder effective drug delivery to the tumor. Recently, scientists found that among the downstream target genes of HIF-1α, the concentration gradient of C-X-C motif ligand 12 (CXCL12) plays a pivotal role in recruiting MSCs expressing the CXCL12 receptor CXCR4 into the tumor microenvironment [29,30,31]. Regarding the direct effects of the hypoxic environment on MSCs, bone marrow, for example, is considered a tissue with limited oxygen supply, and bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs) can be recruited to tumors that reach similarly low oxygen tension. Additionally, growth factors such as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) can also recruit MSCs into the tumor environment [32,33,34]. Other tumor-derived factor like tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) are also involved in MSC tumor-tropism by promoting endothelial adhesion and remodeling the cytoskeletal migration system [35, 36].

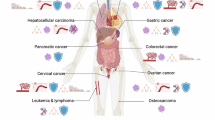

Their inherent ability to home to tumor sites can be harnessed for antitumor treatment, making them suitable for use as cellular therapies to deliver therapeutics directly to tumors. Genetically modified MSCs can function as ‘Trojan horses’ for cancer treatment. By homing to the tumor microenvironment, they can significantly enhance antitumor immunity or response to chemotherapy, while mitigating the toxicity associated with the systemic administration of high doses of cytokines or chemotherapeutic agents. Various strategies can be leveraged to further enhance the efficacy of MSC-based anticancer therapies and to tailor these therapies to the specific needs of different tumors and their microenvironments (Fig. 1).

MSCs are engineered to leverage their tumor-homing capabilities while exhibiting low immunogenicity, facilitating the targeted delivery of therapeutic proteins, microRNAs (miRNAs), prodrugs, and oncolytic viruses directly into the tumor microenvironment and activating antitumor immunity, which aims to enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects. Key advantages of this approach include precise tumor targeting, improved intratumoral penetration, sustained tumoricidal effects, and higher therapeutic safety.

Engineered MSCs for Cancer Treatment

Owing to the tumor tropism of MSCs, research efforts have focused on the genetic modification of MSCs via transfection to facilitate the overexpression of specific therapeutic agents [37, 38]. MSCs are readily amenable to genetic modification through viral vectors. This review will explore the engineering of MSCs through viral transfection-based modifications. The “ammunition” includes a spectrum of therapeutic proteins, microRNAs, prodrugs, chemotherapeutic drugs, suicide genes, and oncolytic viruses. MSCs, acting as efficient carriers, are equipped with these “munitions” which are subsequently delivered to the tumor site. These payloads, either by altering the immune cell landscape within the tumor microenvironment or exerting direct effects on tumor cells, play a crucial role in inhibiting tumor growth or directly inducing tumor cell death (Fig. 2).

MSCs from different sources, including adipose tissue, umbilical cord, bone marrow, dental pulp, and lung, are engineered through viral infection and genetic modification to express therapeutic factors, such as interferons and interleukins, miRNAs, prodrugs, and oncolytic viruses. These engineered MSCs contribute to cancer therapy by modulating tumor biology—enhancing tumor apoptosis, inhibiting angiogenesis, reducing tumor cell migration, and modulating inflammatory infiltration.

Delivery of therapeutic proteins

The tumor microenvironment is characterized by substantial infiltration of diverse immune cell populations, including T cells, B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and macrophages. NK cells are innate immunocytes that directly kill tumors. However, in the highly metabolic environment of tumors, the accumulation of excessive lactate and depletion of amino acids (such as arginine and leucine) impair NK cell function [39]. In addition to metabolic constraints, the tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer contains PGE2 and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which inhibit the activation of DNAX accessory molecule-1 (DNAM-1) and NK cell activating receptors NKp44 and NKp30, thereby suppressing NK cell antitumor effects [40]. Metastatic tumors often evade T cell-mediated killing by downregulating MHC-I expression, thereby reducing antigen presentation and leading to immune therapy failure [41]. CD8+ T cells, recognized as the primary mediators of tumor eradication, frequently exhibit an exhausted phenotype characterized by the co-expression of PD-1 and TIM-3 [42, 43]. In addition to inherent factors contributing to T-cell exhaustion, immunosuppressive factors within the tumor microenvironment, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, can induce the transition of effector and memory T cells into an exhausted state [44, 45]. Researchers have suggested that reversing the exhausted phenotype in CD8+ T cells could potentially enhance tumor suppression. Among therapeutic proteins, cancer-prohibitory interferons and cytokines can achieve highly precise targeted delivery when transported by MSCs (Table 1).

Interferons

Type I and type II interferons are expressed under physiological conditions and are important regulators of immunity and inflammation [46]. On the one hand, type I interferons are known for their pivotal role in antiviral immune responses [47]. Type I interferons promote antigen presentation and NK cell function, while inhibiting proinflammatory pathways and cytokine production. They activate the adaptive immune system, promoting high-affinity antigen-specific T cell and B cell responses and immunological memory [48]. An increasing body of evidence suggests that exogenous type I interferons exhibit antitumor efficacy when administered at specific tumor sites. Ren et al. first genetically engineered MSCs to overexpress IFN-α (IFNα-MSCs) and observed their ability to suppress tumor growth through the induction of apoptosis in both tumor cells and tumor-associated endothelial cells [49]. Furthermore, IFNα-MSCs stimulated the production of CXCL10 in tumor cells, upregulated the expression of granzyme B (GZMB) in CD8+ T cells, and increased the number and cytotoxic activity of infiltrating CD8+ T cells [49, 50]. Similarly, IFNβ-MSCs can directly kill tumor cells independent of the immune system [51]. More importantly, IFNβ-loaded MSCs can initiate a robust antitumor immune response in the tumor microenvironment. IFN-β plays a regulatory role in the expression of TNF-α and IL-12 in peripheral blood monocytes [52]. Additionally, IFN-β modulates the expression of chemokines, including CXCL10, in macrophages [53]. Furthermore, IFNβ-MSCs can enhance NK cell activities [54]. Another study demonstrated that this cell-mediated immunity increases the numbers of splenic mature dendritic cells (DCs) and decreases the numbers of Treg cells [55].

IFN-γ, a type II interferon, was initially believed to possess antitumor effects; however, subsequent research revealed that IFN-γ promotes the expression of inhibitory molecules such as programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), PD-L2, IDO1, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), FAS, and FAS ligand (FASL), all of which limit antitumor immunity [56]. In earlier studies, we found that IFN-γ significantly enhances the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs in immune regulation [57, 58]. Although IFN-γ, as a stimulatory factor for proinflammatory macrophages, can yield promising antitumor effects, caution should be exercised in utilizing IFNγ-MSCs for tumor immunotherapy [38]. Additionally, IFNs can enhance the expression of surface MHC molecules, including in MSCs, and then increase the processing and presentation of tumor-specific antigens, thus facilitating T-cell recognition and cytotoxicity [59, 60]. Given that IFNs are classic cytokines known to induce MSC immunosuppression, caution is warranted on IFNs-overexpression MSCs in cancer therapy.

Interleukins

Engineered MSCs overexpressing cytokines demonstrate potent antitumor effects in various cancer models through mechanisms such as reinvigoration of exhausted tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, augmentation of cytotoxic T cell and NK cell activities, reduction of tumor vascularization, and induction of tumor cell apoptosis and necrosis. MSCs overexpressing IL-2 (IL2-MSCs) exhibited inhibitory effects on glioma and melanoma in murine models, potentially mediated through the involvement of CD8+ T cells within the tumor microenvironment [61, 62]. These MSCs were engineered with the dual objectives of enhancing the homing capacity of MSCs to tumor sites and optimizing the interaction between IL-2 and its respective receptors. In this context, IL2-MSCs reinvigorated exhausted tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) by amplifying the population of PD1+TIM3-CD8+ T cells, while concurrently diminishing the frequency of terminally exhausted T cells and reigniting their cytotoxic functionality [62]. IL-12, a potent proinflammatory cytokine, has garnered extensive attention as a prospective immunotherapeutic agent for cancer. However, initial clinical trials showed that systemic delivery of IL-12 led to dose-limiting toxicities [63]. Thus, local administration of IL12-MSCs demonstrated excellent therapeutic effects in glioma and melanoma. These mechanisms may involve the augmentation of IFN-γ secretion, reduction of vascular density, and increase in proinflammatory macrophages and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) [64, 65]. IL-18 can stimulate T cells and NK cells, prompting them to secrete IFN-γ and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). IL-18 enhances the cytolytic activity of NK cells, promotes the proliferation of T cells, activates CD8+ CTLs, and acts as a chemoattractant for immature DCs. This recruitment is a pivotal event capable of eliciting robust immune responses [66]. Indeed, IL18-overexpressing human UC-MSCs (IL18-hUCMSCs) effectively curtailed tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in the in vitro experiments [67]. Similarly, the introduction of IL-21 into MSCs (IL21-MSCs) substantially augmented NK cytotoxic activity by elevating the secretion of secondary cytokines, including IFN-γ and TNF-α. This effect led to the induction of tumor cell necrosis, apoptosis, and vascular hemorrhage [68, 69]. Additionally, TRAIL-engineered MSCs also showed antitumor effects [70, 71]. These approaches highlight the potential of cytokine-engineered MSCs as innovative and effective strategies for cancer immunotherapy, emphasizing the importance of localized cytokine delivery to minimize systemic toxicities and enhance therapeutic outcomes.

Delivery of miRNA

The interaction between MSCs and tumors can be mediated through extracellular vesicles (EVs). A diverse subset of EVs, especially exosomes, has gained significant attention in recent times [72]. Notably, exosomes, which are ubiquitously present in various body fluids, are characterized by the inheritance of their parental molecular and genetic profiles [73]. Remarkably, exosomes can traverse the blood-brain barrier and reach virtually every region of the human body, an attribute that circumvents a limitation associated with conventional cell-based therapies [74]. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are non-coding RNA molecules known for their diverse roles in various biological processes, primarily through their post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression [75]. The occurrence and progression of tumors are often associated with the up-regulation or down-regulation of various miRNAs. The extensive study of the myriad miRNAs linked to tumorigenesis remains an active area of research. The exosome-derived secretome from MSCs holds significant promise for advancing tumor therapy (Table 2).

The expression of miR-101 is significantly downregulated across a broad spectrum of malignancies. The introduction of miR-101 into MSCs (miR101-MSCs) demonstrated enhanced therapeutic efficacy in osteosarcoma and oral cancer [76, 77]. MiR-125a can directly target specific oncogenes, as reported in various studies [78]. Moreover, miR-125a has been consistently observed to be downregulated in ovarian cancer [79], cervical cancer [80], breast cancer [81], gastric cancer [82], and medulloblastoma [83]. Recently, the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells with exosomes overexpressing miR-125a from miR125a-MSCs has been shown to be efficacious in suppressing vasculogenic mimicry formation in both in vitro and in vivo models [84]. The miR-34 family, directly regulated by the tumor suppressor p53, is recognized as a crucial component in tumor suppression. However, methylation of its promoter region results in miR-34 downregulation, contributing to the pathogenesis of ovarian and colorectal cancers [85, 86]. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is often associated with the downregulation of miR-374c-5p during cancer development [87]. The overexpression of miR-374c-5p in MSCs inhibited EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma through the LIMK1-Wnt/β-catenin axis, halting the occurrence and development of liver cancer [88]. The transcriptional regulator MYB showed heightened expression in ovarian cancer, potentially regulated by reduced levels of miR-424. Exosomes secreted by MSCs overexpressing miR-424 significantly impacted the onset and progression of ovarian cancer, holding promise for clinical applications [89]. Similarly, MSCs with elevated miR-6553p expression have been demonstrated to be effective in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) [90]. Additionally, numerous miRNAs undergo dysregulation in tumorous conditions, underscoring the potential of EVs/exosomes as innate vesicular entities acting as highly effective and promising drug delivery systems for precise and targeted tumor therapy. Overall, engineering MSCs to overexpress specific miRNAs offers an effective approach for cancer treatment, and has therapeutic potential in various cancers by inhibiting tumor progression, promoting apoptosis, and preventing vasculogenic mimicry and EMT through miRNA-mediated modulation of oncogenic pathways and gene expression.

Drug delivery

Prodrugs

Cancer treatment using prodrug delivery methodologies began in the early 1980s [91]. Previous therapeutic approaches were involved in introducing a non-toxic enzyme gene under a tumor-specific promoter. After the administration of a non-toxic prodrug, these enzymes catalyze the conversion of the prodrug into toxic metabolites, leading to programmed cell death in tumor [92, 93]. Prominent systems in this domain include the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/ganciclovir (HSV-TK/GCV) system [94] and the cytosine deaminase/5-fluorocytosine (CD/5-FC) system [95]. However, in solid tumors, gaining access to the innermost tumor cells is a formidable challenge [96]. Tumor proliferation is often rapid and nearly uncontrolled. While the prodrug delivery system can trigger apoptosis, it may also generate a ‘bystander effect’ that affects adjacent cells, potentially diminishing its efficacy against cancer cells [97]. Therefore, this type of clinical treatment has seen slow progress. Exosomes from MSCs have been studied as delivery vehicles [98]. The mRNA of suicide genes carried by exosomes from engineered MSCs was internalized by recipient tumor cells, triggering tumor cell death in the presence of a prodrug [98] (Table 3).

The neurotropism of HSV makes it a widely used agent in the treatment of glioma [99]. This enzyme has a high affinity for ganciclovir and generates triphosphorylated ganciclovir (GCV) when catalyzed by endogenous cellular enzymes [100]. During DNA synthesis, GCV undergoes three phosphorylation steps and is subsequently integrated into DNA strands, impeding DNA chain elongation and ultimately resulting in cell death. Exosomes loaded with herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) from MSCs (HSV-TK/GCV) are internalized by tumor cells. In the presence of the prodrug GCV, these exosomes facilitate the intracellular conversion of ganciclovir into GCV triphosphate, resulting in the death of the recipient tumor cells [101, 102]. This system demonstrates a potent inhibitory effect on glioma and is regarded as a cell-specific drug delivery method that acts within tumor cells [101,102,103].

Cytosine deaminase (CD) is an enzyme found in bacteria and fungi but absent in mammalian cells [92]. 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) can passively diffuse through cellular membranes, thereby inflicting cytotoxicity in cells adjacent to those expressing CD [92, 104]. 5-FU is enzymatically converted to 5-fluoro-2’-deoxyuridine-5’-monophosphate (5-FdUMP) or phosphorylated to 5-fluorouridine-5’-triphosphate (5-FUTP) [105, 106]. These metabolites derived from 5-FC can be incorporated into both RNA and DNA, leading to the inhibition of nuclear processing and inflicting direct damage on newly synthesized DNA strands [106]. While prodrug delivery systems utilizing CD and 5-FC have shown promise in treating certain tumor types, the direct delivery of therapeutic agents to cancer cells within solid tumors is often hindered by irregular vascularization and tight tissue architecture [107]. Engineered MSCs present a plausible solution for converting the prodrug 5-FC into its toxic counterpart 5-FU. Indeed, studies have demonstrated that MSCs engineered with CD/5-FC successfully inhibit the growth of osteosarcoma [108], lung carcinoma [109], and glioma [110]. Overall, prodrug delivery systems in cancer treatment leverage engineered MSCs and exosomes to convert non-toxic prodrugs into toxic metabolites within tumor cells, presenting a targeted approach to induce tumor cell apoptosis despite challenges in treating solid tumors.

Chemotherapy drugs

Chemotherapy is a conventional and widely employed treatment modality. Chemotherapy often carries significant risks and can lead to severe consequences for cancer patients, resembling a balance of “either you kill me or we both die.” Its non-selective nature often results in collateral damage to normal tissues. Therefore, achieving targeted and localized drug delivery has become a primary objective in the field of chemotherapy [111]. Chemotherapeutic agents such as gemcitabine (GCB), paclitaxel (PTX), and doxorubicin (DOX) remain widely used in cancer treatment. In the quest for more effective and less toxic cancer treatments, the engineering of MSCs for targeted drug delivery has emerged as a promising strategy.

GCB is classified as a pyrimidine nucleotide analogue and falls within the category of cancer antimetabolites. Metabolites of GCB inhibit DNA synthesis and prevent cell cycle transition from the G1 phase to the S phase, ultimately leading to apoptosis [112]. Recent evidence showed that GCB loaded within extracellular vesicles derived from dental pulp-derived MSCs (DPMSC-sEV) was as effective as the pure drug and efficiently inhibited pancreatic carcinoma growth in vitro [113]. PTX is a widely used chemotherapy drug with a well-established reputation in clinical practice. It functions by inhibiting cell mitosis through promoting tubulin polymerization and inhibiting tubulin depolymerization. However, delivering PTX specifically to tumor sites has been a significant challenge, prompting researchers to exploit nanometer-scale delivery methods. Despite these advancements, the limited tumor-targeting capacity of these methods has hindered further development in clinical trials. Exposed to high concentrations of PTX in vitro, MSCs can load and deliver the drug via EVs. These results showed that exosomes generated by gingival MSCs can be an ideal vector, delivering high drug concentrations in a minimal volume [114]. This method has been proven effective in pancreatic carcinoma, glioblastoma, mesothelioma, and squamous cell carcinoma [114]. Traditional chemotherapy agents demonstrate enhanced efficacy with reduced side effects when delivered through MSC-derived extracellular vesicles, marking a significant advance in achieving localized treatment. This approach not only addresses the inherent non-selectivity of conventional chemotherapy, which often harms healthy tissues, but also leverages the natural tumor-homing capabilities of MSCs, offering a novel pathway for precision oncology.

Delivery of oncolytic virus

Oncolytic virotherapy, using both genetically modified and naturally occurring viruses, offers a targeted approach to cancer treatment by selectively infecting and lysing tumor cells. Using MSCs as vectors to deliver oncolytic viruses directly to tumors enhances this specificity, overcoming challenges of non-specific retention and systemic toxicity. This strategy has shown promise in treating malignancies such as glioma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and metastatic melanoma, utilizing MSCs’ tumor-homing capabilities and the ability of viruses to induce potent immune responses against cancer cells (Table 4).

The most widely utilized oncolytic virus is the oncolytic adenovirus. Due to the natural affinity of adenoviruses for liver and other organ cells [115], modifications predominantly focus on capsid protein engineering to manipulate viral tropism, to redirect viral infection, to reduce non-specific viral retention in non-tumor locations, and to optimize cellular delivery [116,117,118]. MSCs are ideal vector cells with intrinsic tumor tropism [119], carrying viruses across host defenses and directing them to tumors. Oncolytic viruses have exhibited remarkable therapeutic efficacy in treating malignant intracranial glioma and hepatocellular carcinoma [120, 121]. This therapeutic effect is characterized by heightened immunogenicity and reduced blood circulation duration, addressing non-specific hepatic sequestration and associated liver toxicity. A recent study showed that HSV-armed MSCs were effective in tracking and killing metastatic melanoma cells in the brain [122]. The oncolytic measles virus presents a strong cytopathic effect. Oncolytic measles virus, delivered via MSCs, may inhibit tumor growth through xenogeneic cell fusion. Existing studies have shown that MSCs carrying oncolytic measles virus have a strong inhibitory effect on liver cancer [123] and ovarian cancer [124]. However, further research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms of selectivity and action of oncolytic viruses in this context.

Optimization of Engineered MSCs

The use of engineered MSCs and their exosomes for targeted tumor therapy represents a significant advancement in cancer treatment, providing a platform for the controlled release of therapeutic agents. MSCs have a wide range of sources and are relatively easy to obtain, with lower ethical risks compared to other cell types. For example, MSCs engineered to deliver IL-2 mutein dimer to tumor-infiltrating T cells exhibit capacity to reinvigorate exhausted CD8+ T cells, making it a more potent antitumor therapeutic agent [125]. Concurrently, MSCs were engineered with a hypoxia-inducible promoter and NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), responsible for regulating the production of IL-2 within the tumor microenvironment. This modification not only enhances MSC survival in the challenging tumor microenvironment but also renders these cells more susceptible to β-lap-mediated cytotoxicity, offering a new therapeutic paradigm. Additionally, due to the complexity of the tumor microenvironment and the heterogeneous expression patterns of solid tumor antigens, any strategy relying solely on a single effector targeting one antigen may not achieve complete tumor eradication [126]. The team of M. Suzuki presents a novel binary vector containing OAd and HDAd (a helper-dependent Ad), which directly kills tumors, activates the immune response through IL-12, and facilitates PD-L1 immune checkpoint therapy [127, 128]. This implies that the vector potential of MSCs can be augmented through the integration of oncolytic virus therapy, cytokine therapy, and immune checkpoint therapy.

Although engineered MSC exosomes exhibit the drawbacks of limited circulatory lifespan and suboptimal targeting efficiency [129], their transformation is undergoing significant progress through surface alterations, peptide insertion, and chemical modifications. The incorporation of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) serves to protect exosomal surface proteins against proteolytic degradation and facilitates the targeted delivery of exosomes to tumor tissues [130]. The specificity and circulation time of exosomes modified with PEGylated liposomes were significantly prolonged [131]. Diverse tumor cells exhibit distinct antigen profiles, some of which are exclusive to tumor cells and others characteristic of specific tumor types. Therefore, incorporating antibodies that can selectively bind to tumor antigens on exosome surfaces is a promising strategy.

The immunoregulatory function of MSCs is highly plastic. After being recruited by chemokines in the tumor microenvironment, the immunosuppressive niche initially created by MSCs is reversed by the factors they produce following transformation [132]. Inflammatory cytokines upregulate MSCs to express PD-L1 or induce the expression of PD-L1 in tumors, thereby conferring immunosuppressive properties [133]. This mechanism offers potential for combination with immune checkpoint blockade therapies [134, 135]. In contrast, certain tissue-derived MSCs may exert immunosupportive effects on immune cells [136]. Thus, a better understanding of the plasticity of immunoregulation by MSCs will help optimize strategies for MSC applications in tumor treatment. Overloading IFNs or other drugs inevitably lead to induced intratumoral IFN production. Consequently, the precise role of upregulated MSC histocompatibility complex in the tumor microenvironment, whether it operates in a “hit-and-run” manner or through “long-lasting release,” remains unclear. Additionally, investigating the alterations in the tumor microenvironment following engineered MSC treatment will provide further evidence to support the combination of immune checkpoint blockade therapy and the clinical application of MSCs [50, 125, 128].

Current therapeutic strategies involve isolating MSCs in vitro, followed by the establishment of stable cell lines to enable large-scale expansion. After validation in animal models, these approaches hold the potential to advance into clinical trials (Fig. 3). Despite these advances, MSCs and MSC-derived exosomes have demonstrated limitations in targeting efficiency and therapeutic potential. Further investigations are needed to fully harness the potential of MSC-based therapies in oncology for clinical applications.

Initially, the preparation and modification of MSCs involve meticulous donor selection, considering factors such as health status, genetic background, sex, age, and tissue origin. Subsequently, bioengineering approaches—such as particle engineering, genetic modifications, and oncolytic virus incorporation—are integrated into standardized manufacturing processes to produce engineered MSCs. In the intermediate stage, rigorous quality control measures and potency assessments are conducted. These steps include monitoring cell viability, ensuring genetic stability, and evaluating the release of biologic factors, along with conducting in vitro and in vivo efficacy tests. Characterization of the immune microenvironment and tumorigenic phenotypes further elucidates the therapeutic potential and underlying mechanisms of action. Finally, during clinical trials and application, patient stratification is performed based on factors such as pathological grading, disease stage and severity, prior treatments, drug susceptibility, and oncogenomic profiles. This stratification enables the formulation of personalized therapeutic regimens, incorporating synergistic treatment strategies, tailored administration routes, continuous tumor monitoring, nutritional support, and clinical follow-up. Together, these steps enable the safe, effective, and precise translation of engineered MSC therapies from bench to bedside.

Conclusions

The exploration and utilization of MSCs have marked a significant advancement in cancer therapy, bridging decades of research from their initial discovery in bone marrow stroma to their identification across various tissues. MSCs have demonstrated remarkable versatility, not only in their differentiation potential across mesenchymal and non-mesodermal cell types but also in their ability to interact with and modulate the tumor microenvironment. The development and application of engineered MSCs have opened new avenues for targeted cancer treatment, utilizing their low immunogenicity and innate tumor tropism. Another important aspect is that engineered MSCs secrete cytokines that increase the number of memory T cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes, thereby enhancing long-term immune surveillance [50]. Moreover, these cells elevate the expression of tumor PD-L1 or T cell PD-1 when combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors, a strategy that has shown superior outcomes in tumor therapy [50, 125]. Engineered MSCs, through viral transfection or other modification techniques, have been tailored to deliver a wide array of therapeutic agents—including therapeutic proteins, miRNAs, prodrugs, chemotherapy drugs, and oncolytic viruses—directly to the tumor site. Innovations in exosome modification, surface alterations, and the incorporation of specific targeting moieties aim to refine the delivery of therapeutic agents and increase the precision of MSC-based therapies. Despite the promising outcomes of MSC-based therapies in preclinical research and clinical trials, challenges remain. For instance, the heterogeneity of MSCs derived from different tissue sources can lead to unpredictable therapeutic outcomes [136]. Additionally, it is essential to assess whether the homing ability and proliferative potential of genetically modified MSCs remain consistent after in vitro expansion, compared to their pre-modification state. Furthermore, it is crucial to examine whether external signaling cues or intercellular communication could trigger inappropriate differentiation of these cells. Therefore, it is vital to establish standardized protocols and rigorous evaluation criteria for the application of engineered MSCs in cancer therapy, aiming to effectively eradicate tumors while minimizing the risk of adverse effects.

The journey of MSCs from discovery to therapeutic agents in cancer treatment exemplifies the dynamic interplay between scientific innovation and clinical application. While significant progress has been made, ongoing research and development are crucial to fully harness the potential of engineered MSCs in revolutionizing cancer therapy, establishing it as a promising frontier in precision oncology.

References

Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhjan RK, Lalykina KS. The development of fibroblast colonies in monolayer cultures of guinea-pig bone marrow and spleen cells. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1970;3:393–403.

Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:641–50.

Lee OK, Kuo TK, Chen WM, Lee KD, Hsieh SL, Chen TH. Isolation of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2004;103:1669–75.

Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, De Ugarte DA, Huang JI, Mizuno H, et al. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4279–95.

Dicker A, Le Blanc K, Astrom G, van Harmelen V, Gotherstrom C, Blomqvist L, et al. Functional studies of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult human adipose tissue. Exp Cell Res. 2005;308:283–90.

Pierdomenico L, Bonsi L, Calvitti M, Rondelli D, Arpinati M, Chirumbolo G, et al. Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells with immunosuppressive activity can be easily isolated from dental pulp. Transplantation. 2005;80:836–42.

Rebelatto CK, Aguiar AM, Moretao MP, Senegaglia AC, Hansen P, Barchiki F, et al. Dissimilar differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, and adipose tissue. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2008;233:901–13.

Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–7.

Gu LH, Zhang TT, Li Y, Yan HJ, Qi H, Li FR. Immunogenicity of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells transplanted via different routes in diabetic rats. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:444–55.

Viswanathan S, Shi Y, Galipeau J, Krampera M, Leblanc K, Martin I, et al. Mesenchymal stem versus stromal cells: International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT(R)) Mesenchymal Stromal Cell committee position statement on nomenclature. Cytotherapy. 2019;21:1019–24.

Viswanathan S, Blanc KL, Ciccocioppo R, Dagher G, Filiano AJ, Galipeau J, et al. An International Society for Cell and Gene Therapy Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSC) Committee perspectives on International Standards Organization/Technical Committee 276 Biobanking Standards for bone marrow-MSCs and umbilical cord tissue-derived MSCs for research purposes. Cytotherapy. 2023;25:803–7.

Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–7.

Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, Gotherstrom C, Hassan M, Uzunel M, et al. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363:1439–41.

Sun L, Wang D, Liang J, Zhang H, Feng X, Wang H, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in severe and refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2467–75.

Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:726–36.

Ankrum J, Karp JM. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy: Two steps forward, one step back. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:203–9.

Dvorak HF, Flier J, Frank H. Tumors - Wounds That Do Not Heal - Similarities between Tumor Stroma Generation and Wound-Healing. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1650–9.

Ren GW, Zhao X, Wang Y, Zhang X, Chen XD, Xu CL, et al. CCR2-Dependent Recruitment of Macrophages by Tumor-Educated Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Promotes Tumor Development and Is Mimicked by TNFα. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:812–24.

Kidd S, Spaeth E, Dembinski JL, Dietrich M, Watson K, Klopp A, et al. Direct evidence of mesenchymal stem cell tropism for tumor and wounding microenvironments using in vivo bioluminescent imaging. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2614–23.

Shah K. Mesenchymal stem cells engineered for cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:739–48.

Svajger U, Kamensek U. Interleukins and interferons in mesenchymal stromal stem cell-based gene therapy of cancer. Cytokine Growth F R. 2024;77:76–90.

Weng ZJ, Zhang BW, Wu CZ, Yu FY, Han B, Li B, et al. Therapeutic roles of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:136.

Xiao Y, Yu DH. Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer. Pharmacol Therapeut. 2021;221:107753.

Dvorak HF. Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1650–9.

Michieli P. Hypoxia, angiogenesis and cancer therapy: to breathe or not to breathe? Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3291–6.

Thomlinson RH, Gray LH. The Histological Structure of Some Human Lung Cancers and the Possible Implications for Radiotherapy. Brit J Cancer. 1955;9:539–49.

Goethals L, Debucquoy A, Perneel C, Geboes K, Ectors N, De Schutter H, et al. Hypoxia in human colorectal adenocarcinoma: Comparison between extrinsic and potential intrinsic hypoxia markers. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2006;65:246–54.

Walsh JC, Lebedev A, Aten E, Madsen K, Marciano L, Kolb HC. The Clinical Importance of Assessing Tumor Hypoxia: Relationship of Tumor Hypoxia to Prognosis and Therapeutic Opportunities. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2014;21:1516–54.

Ceradini DJ, Gurtner GC. Homing to hypoxia: HIF-1 as a mediator of progenitor cell recruitment to injured tissue. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:57–63.

Liu L, Yu Q, Lin J, Lai X, Cao W, Du K, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha is essential for hypoxia-induced mesenchymal stem cell mobilization into the peripheral blood. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1961–71.

Babazadeh S, Nassiri SM, Siavashi V, Sahlabadi M, Hajinasrollah M, Zamani-Ahmadmahmudi M. Macrophage polarization by MSC-derived CXCL12 determines tumor growth. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2021;26:30.

Spaeth E, Klopp A, Dembinski J, Andreeff M, Marini F. Inflammation and tumor microenvironments: defining the migratory itinerary of mesenchymal stem cells. Gene Ther. 2008;15:730–8.

Naaldijk Y, Johnson AA, Ishak S, Meisel HJ, Hohaus C, Stolzing A. Migrational changes of mesenchymal stem cells in response to cytokines, growth factors, hypoxia, and aging. Exp Cell Res. 2015;338:97–104.

Lu JH, Zhang Y, Wang DY, Xu XJ, Xu JW, Yang XY, et al. Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor Promotes Mesenchymal Stem Cell Migration by Regulating Glycolysis-Dependent β-Catenin Signaling. Stem Cells. 2023;41:628–42.

Ho IAW, Chan KYW, Ng WH, Guo CM, Hui KM, Cheang P, et al. Matrix Metalloproteinase 1 Is Necessary for the Migration of Human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Toward Human Glioma. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1366–75.

Rattigan Y, Hsu JM, Mishra PJ, Glod J, Banerjee D. Interleukin 6 mediated recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells to the hypoxic tumor milieu. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:3417–24.

Li Z, Fan D, Xiong D. Mesenchymal stem cells as delivery vectors for anti-tumor therapy. Stem Cell Investig. 2015;2:6.

Relation T, Yi T, Guess AJ, La Perle K, Otsuru S, Hasgur S, et al. Intratumoral Delivery of Interferongamma-Secreting Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Repolarizes Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Suppresses Neuroblastoma Proliferation In Vivo. Stem Cells. 2018;36:915–24.

Terrén I, Orrantia A, Vitallé J, Zenarruzabeitia O, Borrego F. NK Cell Metabolism and Tumor Microenvironment. Front Immuno. 2019;10:2278.

Caligiuri G, Tuveson DA. Activated fibroblasts in cancer: Perspectives and challenges. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:434–49.

Baldominos P, Barbera-Mourelle A, Barreiro O, Huang Y, Wight A, Cho J-W, et al. Quiescent cancer cells resist T cell attack by forming an immunosuppressive niche. Cell. 2022;185:1694–1708.e1619.

Dolina JS, Van Braeckel-Budimir N, Thomas GD, Salek-Ardakani S. CD8(+) T Cell Exhaustion in Cancer. Front Immunol. 2021;12:715234.

Jiang W, He Y, He W, Wu G, Zhou X, Sheng Q, et al. Exhausted CD8+T Cells in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment: New Pathways to Therapy. Front Immunol. 2020;11:622509.

Annacker O, Asseman C, Read S, Powrie F. Interleukin-10 in the regulation of T cell-induced colitis. J Autoimmun. 2003;20:277–9.

Thomas DA, Massague J. TGF-beta directly targets cytotoxic T cell functions during tumor evasion of immune surveillance. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:369–80.

Barrat FJ, Crow MK, Ivashkiv LB. Interferon target-gene expression and epigenomic signatures in health and disease. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:1574–83.

Aref S, Castleton AZ, Bailey K, Burt R, Dey A, Leongamornlert D, et al. Type 1 Interferon Responses Underlie Tumor-Selective Replication of Oncolytic Measles Virus. Mol Ther. 2020;28:1043–55.

Ivashkiv LB, Donlin LT. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;14:36–49.

Ren C, Kumar S, Chanda D, Chen J, Mountz JD, Ponnazhagan S. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells producing interferon-alpha in a mouse melanoma lung metastasis model. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2332–8.

Zhang T, Wang Y, Li Q, Lin L, Xu C, Xue Y, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells equipped by IFNalpha empower T cells with potent anti-tumor immunity. Oncogene. 2022;41:1866–81.

Studeny M, Marini FC, Champlin RE, Zompetta C, Fidler IJ, Andreeff M. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells as vehicles for interferon-beta delivery into tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3603–8.

Rudick RA, Ransohoff RM, Peppler R, VanderBrug Medendorp S, Lehmann P, Alam J. Interferon beta induces interleukin-10 expression: relevance to multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:618–27.

Jungo F, Dayer JM, Modoux C, Hyka N, Burger D. IFN-beta inhibits the ability of T lymphocytes to induce TNF-alpha and IL-1beta production in monocytes upon direct cell-cell contact. Cytokine. 2001;14:272–82.

Ren C, Kumar S, Chanda D, Kallman L, Chen J, Mountz JD, et al. Cancer gene therapy using mesenchymal stem cells expressing interferon-beta in a mouse prostate cancer lung metastasis model. Gene Ther. 2008;15:1446–53.

Ling X, Marini F, Konopleva M, Schober W, Shi Y, Burks J, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Overexpressing IFN-beta Inhibit Breast Cancer Growth and Metastases through Stat3 Signaling in a Syngeneic Tumor Model. Cancer Microenviron. 2010;3:83–95.

Ivashkiv LB. IFNγ: signalling, epigenetics and roles in immunity, metabolism, disease and cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:545–58.

Ren G, Zhang L, Zhao X, Xu G, Zhang Y, Roberts AI, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Mediated Immunosuppression Occurs via Concerted Action of Chemokines and Nitric Oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:141–50.

Shi Y, Hu G, Su J, Li W, Chen Q, Shou P, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: a new strategy for immunosuppression and tissue repair. Cell Res. 2010;20:510–8.

Shankaran V, Ikeda H, Bruce AT, White JM, Swanson PE, Old LJ, et al. IFNgamma and lymphocytes prevent primary tumour development and shape tumour immunogenicity. Nature. 2001;410:1107–11.

Xu C, Lin L, Cao G, Chen Q, Shou P, Huang Y, et al. Interferon-α-secreting mesenchymal stem cells exert potent antitumor effect in vivo. Oncogene. 2014;33:5047–52.

Nakamura K, Ito Y, Kawano Y, Kurozumi K, Kobune M, Tsuda H, et al. Antitumor effect of genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cells in a rat glioma model. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1155–64.

Stagg J, Lejeune L, Paquin A, Galipeau J. Marrow stromal cells for interleukin-2 delivery in cancer immunotherapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:597–608.

Nguyen KG, Vrabel MR, Mantooth SM, Hopkins JJ, Wagner ES, Gabaldon TA, et al. Localized Interleukin-12 for Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2020;11:575597.

Ryu CH, Park SH, Park SA, Kim SM, Lim JY, Jeong CH, et al. Gene therapy of intracranial glioma using interleukin 12-secreting human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22:733–43.

Kulach N, Pilny E, Cichon T, Czapla J, Jarosz-Biej M, Rusin M, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells as carriers of IL-12 reduce primary and metastatic tumors of murine melanoma. Sci Rep. 2021;11:18335.

Li Z, Yu X, Werner J, Bazhin AV, D’Haese JG. The role of interleukin-18 in pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2019;50:1–12.

Liu X, Hu J, Sun S, Li F, Cao W, Wang YU, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells expressing interleukin-18 suppress breast cancer cells in vitro. Exp Therapeutic Med. 2015;9:1192–1200.

Hu W, Wang J, He X, Zhang H, Yu F, Jiang L, et al. Human umbilical blood mononuclear cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells serve as interleukin-21 gene delivery vehicles for epithelial ovarian cancer therapy in nude mice. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2011;58:397–404.

Zhang Y, Wang J, Ren M, Li M, Chen D, Chen J, et al. Gene therapy of ovarian cancer using IL-21-secreting human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in nude mice. J Ovarian Res. 2014;7:8.

Kim SM, Lim JY, Park SI, Jeong CH, Oh JH, Jeong M, et al. Gene therapy using TRAIL-secreting human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells against intracranial glioma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9614–23.

Un Choi Y, Yoon Y, Jung PY, Hwang S, Hong JE, Kim WS, et al. TRAIL-overexpressing Adipose Tissue-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Efficiently Inhibit Tumor Growth in an H460 Xenograft Model. Cancer Genomics Proteom. 2021;18:569–78.

Whiteside TL. Exosome and mesenchymal stem cell cross-talk in the tumor microenvironment. Semin Immunol. 2018;35:69–79.

Yu B, Zhang X, Li X. Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:4142–57.

Do AD, Kurniawati I, Hsieh CL, Wong TT, Lin YL, Sung SY. Application of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Targeted Delivery to the Brain: Potential and Challenges of the Extracellular Vesicle-Based Approach for Brain Tumor Treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:11187.

Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W. The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:597–610.

Xie C, Du LY, Guo F, Li X, Cheng B. Exosomes derived from microRNA-101-3p-overexpressing human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells suppress oral cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and migration. Mol Cell Biochem. 2019;458:11–26.

Zhang K, Dong C, Chen M, Yang T, Wang X, Gao Y, et al. Extracellular vesicle-mediated delivery of miR-101 inhibits lung metastasis in osteosarcoma. Theranostics. 2020;10:411–25.

Wang JK, Wang Z, Li G. MicroRNA-125 in immunity and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019;454:134–45.

Yang J, Li G, Zhang K. MiR-125a regulates ovarian cancer proliferation and invasion by repressing GALNT14 expression. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;80:381–7.

Fan Z, Cui H, Xu X, Lin Z, Zhang X, Kang L, et al. MiR-125a suppresses tumor growth, invasion and metastasis in cervical cancer by targeting STAT3. Oncotarget. 2015;6:25266–80.

Li W, Duan R, Kooy F, Sherman SL, Zhou W, Jin P. Germline mutation of microRNA-125a is associated with breast cancer. J Med Genet. 2009;46:358–60.

Nishida N, Mimori K, Fabbri M, Yokobori T, Sudo T, Tanaka F, et al. MicroRNA-125a-5p is an independent prognostic factor in gastric cancer and inhibits the proliferation of human gastric cancer cells in combination with trastuzumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2725–33.

Ferretti E, De Smaele E, Po A, Di Marcotullio L, Tosi E, Espinola MS, et al. MicroRNA profiling in human medulloblastoma. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:568–77.

Wan F, Zhang H, Hu J, Chen L, Geng S, Kong L, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Inhibits Migration and Vasculogenic Mimicry in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Via Exosomal MiR-125a. Front Oncol. 2022;12:781979.

Corney DC, Hwang CI, Matoso A, Vogt M, Flesken-Nikitin A, Godwin AK, et al. Frequent downregulation of miR-34 family in human ovarian cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1119–28.

Bu P, Wang L, Chen KY, Srinivasan T, Murthy PK, Tung KL, et al. A miR-34a-Numb Feedforward Loop Triggered by Inflammation Regulates Asymmetric Stem Cell Division in Intestine and Colon Cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:189–202.

Li Q, Wang C, Cai L, Lu J, Zhu Z, Wang C, et al. miR‑34a derived from mesenchymal stem cells stimulates senescence in glioma cells by inducing DNA damage. Mol Med Rep. 2019;19:1849–57.

Ding BS, Lou WY, Fan WM, Pan J. Exosomal miR-374c-5p derived from mesenchymal stem cells suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinoma via the LIMK1-Wnt/beta-catenin axis. Environ Toxicol. 2023;38:1038–52.

Li P, Xin H, Lu L. Extracellular vesicle-encapsulated microRNA-424 exerts inhibitory function in ovarian cancer by targeting MYB. J Transl Med. 2021;19:4.

Chen M, Xia Z, Deng J. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles carrying miR-655-3p inhibit the development of esophageal cancer by regulating the expression of HIF-1alpha via a LMO4/HDAC2-dependent mechanism. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2023;39:1319–39.

Carl PL, Chakravarty PK, Katzenellenbogen JA, Weber MJ. Protease-activated “prodrugs” for cancer chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:2224–8.

Portsmouth D, Hlavaty J, Renner M. Suicide genes for cancer therapy. Mol Asp Med. 2007;28:4–41.

Xu G, McLeod HL. Strategies for enzyme/prodrug cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3314–24.

Beltinger C, Fulda S, Kammertoens T, Meyer E, Uckert W, Debatin KM. Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/ganciclovir-induced apoptosis involves ligand-independent death receptor aggregation and activation of caspases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8699–704.

Ostertag D, Amundson KK, Lopez Espinoza F, Martin B, Buckley T, Galvao da Silva AP, et al. Brain tumor eradication and prolonged survival from intratumoral conversion of 5-fluorocytosine to 5-fluorouracil using a nonlytic retroviral replicating vector. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:145–59.

Karjoo Z, Chen X, Hatefi A. Progress and problems with the use of suicide genes for targeted cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;99:113–28.

Floeth FW, Shand N, Bojar H, Prisack HB, Felsberg J, Neuen-Jacob E, et al. Local inflammation and devascularization-in vivo mechanisms of the “bystander effect” in VPC-mediated HSV-Tk/GCV gene therapy for human malignant glioma. Cancer Gene Ther. 2001;8:843–51.

Altanerova U, Jakubechova J, Benejova K, Priscakova P, Pesta M, Pitule P, et al. Prodrug suicide gene therapy for cancer targeted intracellular by mesenchymal stem cell exosomes. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:897–908.

Grandi P, Peruzzi P, Reinhart B, Cohen JB, Chiocca EA, Glorioso JC. Design and application of oncolytic HSV vectors for glioblastoma therapy. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:505–17.

Oishi T, Ito M, Koizumi S, Horikawa M, Yamamoto T, Yamagishi S, et al. Efficacy of HSV-TK/GCV system suicide gene therapy using SHED expressing modified HSV-TK against lung cancer brain metastases. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2022;26:253–65.

Pastorakova A, Jakubechova J, Altanerova U, Altaner C. Suicide Gene Therapy Mediated with Exosomes Produced by Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells Stably Transduced with HSV Thymidine Kinase. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:1096.

Song C, Xiang J, Tang J, Hirst DG, Zhou J, Chan KM, et al. Thymidine kinase gene modified bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells as vehicles for antitumor therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22:439–49.

de Melo SM, Bittencourt S, Ferrazoli EG, da Silva CS, da Cunha FF, da Silva FH, et al. The Anti-Tumor Effects of Adipose Tissue Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transduced with HSV-Tk Gene on U-87-Driven Brain Tumor. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128922.

Ramnaraine M, Pan W, Goblirsch M, Lynch C, Lewis V, Orchard P, et al. Direct and bystander killing of sarcomas by novel cytosine deaminase fusion gene. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6847–54.

Chen JK, Hu LJ, Wang D, Lamborn KR, Deen DF. Cytosine deaminase/5-fluorocytosine exposure induces bystander and radiosensitization effects in hypoxic glioblastoma cells in vitro. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:1538–47.

Boucher PD, Im MM, Freytag SO, Shewach DS. A novel mechanism of synergistic cytotoxicity with 5-fluorocytosine and ganciclovir in double suicide gene therapy. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3230–7.

Altaner C. Prodrug cancer gene therapy. Cancer Lett. 2008;270:191–201.

NguyenThai QA, Sharma N, Luong DH, Sodhi SS, Kim JH, Kim N, et al. Targeted inhibition of osteosarcoma tumor growth by bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells expressing cytosine deaminase/5-fluorocytosine in tumor-bearing mice. J Gene Med. 2015;17:87–99.

Krassikova LS, Karshieva SS, Cheglakov IB, Belyavsky AV. Combined treatment, based on lysomustine administration with mesenchymal stem cells expressing cytosine deaminase therapy, leads to pronounced murine Lewis lung carcinoma growth inhibition. J Gene Med. 2016;18:220–33.

Chung T, Na J, Kim YI, Chang DY, Kim YI, Kim H, et al. Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase Is a Prognostic Marker for Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Mediated Cytosine Deaminase Gene and 5-Fluorocytosine Prodrug Therapy for the Treatment of Recurrent Gliomas. Theranostics. 2016;6:1477–90.

Goldberg EP, Hadba AR, Almond BA, Marotta JS. Intratumoral cancer chemotherapy and immunotherapy: opportunities for nonsystemic preoperative drug delivery. J Pharm Pharm. 2002;54:159–80.

Plunkett W, Huang P, Xu YZ, Heinemann V, Grunewald R, Gandhi V. Gemcitabine: metabolism, mechanisms of action, and self-potentiation. Semin Oncol. 1995;22:3–10.

Klimova D, Jakubechova J, Altanerova U, Nicodemou A, Styk J, Szemes T, et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from dental mesenchymal stem/stromal cells with gemcitabine as a cargo have an inhibitory effect on the growth of pancreatic carcinoma cell lines in vitro. Mol Cell Probes. 2023;67:101894.

Cocce V, Franze S, Brini AT, Gianni AB, Pascucci L, Ciusani E, et al. In Vitro Anticancer Activity of Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) Secreted by Gingival Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Primed with Paclitaxel. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11:61.

Martin K, Brie A, Saulnier P, Perricaudet M, Yeh P, Vigne E. Simultaneous CAR- and alpha V integrin-binding ablation fails to reduce Ad5 liver tropism. Mol Ther. 2003;8:485–94.

Korokhov N, Mikheeva G, Krendelshchikov A, Belousova N, Simonenko V, Krendelshchikova V, et al. Targeting of adenovirus via genetic modification of the viral capsid combined with a protein bridge. J Virol. 2003;77:12931–40.

Kreppel F, Gackowski J, Schmidt E, Kochanek S. Combined genetic and chemical capsid modifications enable flexible and efficient de- and retargeting of adenovirus vectors. Mol Ther. 2005;12:107–17.

Pereboeva L, Curiel DT. Cellular vehicles for cancer gene therapy: current status and future potential. BioDrugs. 2004;18:361–85.

Hakkarainen T, Sarkioja M, Lehenkari P, Miettinen S, Ylikomi T, Suuronen R, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells lack tumor tropism but enhance the antitumor activity of oncolytic adenoviruses in orthotopic lung and breast tumors. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:627–41.

Sonabend AM, Ulasov IV, Tyler MA, Rivera AA, Mathis JM, Lesniak MS. Mesenchymal stem cells effectively deliver an oncolytic adenovirus to intracranial glioma. Stem Cells. 2008;26:831–41.

Yoon AR, Hong J, Li Y, Shin HC, Lee H, Kim HS, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Mediated Delivery of an Oncolytic Adenovirus Enhances Antitumor Efficacy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2019;79:4503–14.

Du WL, Seah I, Bougazzoul O, Choi GH, Meeth K, Bosenberg MW, et al. Stem cell-released oncolytic herpes simplex virus has therapeutic efficacy in brain metastatic melanomas. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E6157–E6165.

Ong HT, Federspiel MJ, Guo CM, Ooi LL, Russell SJ, Peng KW, et al. Systemically delivered measles virus-infected mesenchymal stem cells can evade host immunity to inhibit liver cancer growth. J Hepatol. 2013;59:999–1006.

Mader EK, Maeyama Y, Lin Y, Butler GW, Russell HM, Galanis E, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Carriers Protect Oncolytic Measles Viruses from Antibody Neutralization in an Orthotopic Ovarian Cancer Therapy Model. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7246–55.

Bae J, Liu L, Moore C, Hsu E, Zhang A, Ren Z, et al. IL-2 delivery by engineered mesenchymal stem cells re-invigorates CD8(+) T cells to overcome immunotherapy resistance in cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2022;24:1754–65.

Lorenzo-Sanz L, Muñoz P. Tumor-Infiltrating Immunosuppressive Cells in Cancer-Cell Plasticity, Tumor Progression and Therapy Response. Cancer Microenviron. 2019;12:119–32.

Rosewell Shaw A, Porter CE, Watanabe N, Tanoue K, Sikora A, Gottschalk S, et al. Adenovirotherapy Delivering Cytokine and Checkpoint Inhibitor Augments CAR T Cells against Metastatic Head and Neck Cancer. Mol Ther. 2017;25:2440–51.

McKenna MK, Englisch A, Brenner B, Smith T, Hoyos V, Suzuki M, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell delivery of oncolytic immunotherapy improves CAR-T cell antitumor activity. Mol Ther. 2021;29:1808–20.

Zhao M, van Straten D, Broekman MLD, Preat V, Schiffelers RM. Nanocarrier-based drug combination therapy for glioblastoma. Theranostics. 2020;10:1355–72.

Vidal M. Exosomes and GPI-anchored proteins: Judicious pairs for investigating biomarkers from body fluids. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;161-162:110–23.

Kooijmans SAA, Fliervoet LAL, van der Meel R, Fens M, Heijnen HFG, van Bergen En Henegouwen PMP, et al. PEGylated and targeted extracellular vesicles display enhanced cell specificity and circulation time. J Control Release. 2016;224:77–85.

Jung Y, Kim JK, Shiozawa Y, Wang J, Mishra A, Joseph J, et al. Recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells into prostate tumours promotes metastasis. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1795.

Wang S, Wang G, Zhang L, Li F, Liu K, Wang Y, et al. Interleukin-17 promotes nitric oxide-dependent expression of PD-L1 in mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Biosci. 2020;10:73.

Zhang Q, Zhang J, Wang P, Zhu G, Jin G, Liu F. Glioma-associated mesenchymal stem cells-mediated PD-L1 expression is attenuated by Ad5-Ki67/IL-15 in GBM treatment. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13:284.

Sun L, Huang C, Zhu M, Guo S, Gao Q, Wang Q, et al. Gastric cancer mesenchymal stem cells regulate PD-L1-CTCF enhancing cancer stem cell-like properties and tumorigenesis. Theranostics. 2020;10:11950–62.

He Y, Qu Y, Meng B, Huang W, Tang J, Wang R, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells empower T cells in the lymph nodes via MCP-1/PD-L1 axis. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13:365.

Choi SH, Stuckey DW, Pignatta S, Reinshagen C, Khalsa JK, Roozendaal N, et al. Tumor Resection Recruits Effector T Cells and Boosts Therapeutic Efficacy of Encapsulated Stem Cells Expressing IFNbeta in Glioblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:7047–58.

Quiroz-Reyes AG, Gonzalez-Villarreal CA, Limon-Flores AY, Delgado-Gonzalez P, Martinez-Rodriguez HG, Said-Fernandez SL, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Genetically Modified by Lentivirus-Express Soluble TRAIL and Interleukin-12 Inhibit Growth and Reduced Metastasis-Relate Changes in Lymphoma Mice Model. Biomedicines. 2023;11:595.

Sheykhhasan M, Kalhor N, Sheikholeslami A, Dolati M, Amini E, Fazaeli H. Exosomes of Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Proper Vehicle for Transfecting miR-145 into the Breast Cancer Cell Line and Its Effecton Metastasis. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:5516078.

Li L, Guan Y, Liu H, Hao N, Liu T, Meng X, et al. Silica nanorattle-doxorubicin-anchored mesenchymal stem cells for tumor-tropic therapy. ACS Nano. 2011;5:7462–70.

Wei HX, Chen JY, Wang SL, Fu FH, Zhu X, Wu CY, et al. A Nanodrug Consisting Of Doxorubicin And Exosome Derived From Mesenchymal Stem Cells For Osteosarcoma Treatment In Vitro. Int J Nanomed. 2019;14:8603–10.

Josiah DT, Zhu D, Dreher F, Olson J, McFadden G, Caldas H. Adipose-derived stem cells as therapeutic delivery vehicles of an oncolytic virus for glioblastoma. Mol Ther. 2010;18:377–85.

Kazimirsky G, Jiang W, Slavin S, Ziv-Av A, Brodie C. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance the oncolytic effect of Newcastle disease virus in glioma cells and glioma stem cells via the secretion of TRAIL. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7:149.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82430086, 82202032 and U24A20379), National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1100600 and 2022YFA0807300), Basic Research Program of Jiangsu Province (BK20243007), Jiangsu Province International Joint Laboratory for Regenerative Medicine Fund, Suzhou Foreign Academician Workstation Fund (SWY202202) and Foundation and Frontier Innovation Interdisciplinary Research Special Project of Suzhou Medical College, Soochow University (YXY2303020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuzhu Shi and Jia Zhang drafted this review and designed the figures through BioRender; Yanan Li contributed to literature search; Chao Feng gave some valuable suggestions; Changshun Shao, Yufang Shi and Jiankai Fang provided the design and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed to publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Edited by Professor Gerry Melino

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Y., Zhang, J., Li, Y. et al. Engineered mesenchymal stem/stromal cells against cancer. Cell Death Dis 16, 113 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-025-07443-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-025-07443-0

This article is cited by

-

Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for end-stage liver disease: adversity and opportunity

Stem Cell Research & Therapy (2025)

-

ARM-X: an adaptable mesenchymal stromal cell-based vaccination platform suitable for solid tumors

Stem Cell Research & Therapy (2025)

-

Harnessing engineered mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles for innovative cancer treatments

Stem Cell Research & Therapy (2025)

-

Generation of hTERT-immortalized human mesenchymal stromal cells with optical and magnetic labels for in vivo transplantation and tracking

Stem Cell Research & Therapy (2025)

-

MiR-145 encapsulated small extracellular vesicles inhibit colorectal cancer progression by downregulating fascin actin-bundling protein 1 expression

Stem Cell Research & Therapy (2025)