Abstract

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are heterogeneous hematopoietic stem cell disorders defined by ineffective hematopoiesis, multilineage dysplasia, and risk of progression to acute myeloid leukemia. Improvements have been made to identify recurrent genetic mutations and their functional roles, but translating this into preclinical models is still difficult. Traditional murine systems lack the human-specific cytokine support and microenvironmental support that is necessary to reproduce MDS pathophysiology. Humanized mouse models, particularly those incorporating human cytokines (e.g., MISTRG, NSG-SGM3, NOG-EXL), immunodeficient backgrounds, and co-transplantation strategies, have improved the engraftment and differentiation of human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. These models allow the study of clonal evolution, mutation-specific disease dynamics, and response to therapies in vivo. However, difficulties persist, such as limited long-term engraftment, incomplete immune reconstruction, and limited possibilities of modeling early-stage or low-risk MDS. This review presents an overview of current humanized and genetically engineered mouse models suitable for studying MDS, evaluating their capacity to replicate disease complexity, preserve clonal architecture, and support translational research. We highlight the need to develop new approaches to improve the actual methodologies and propose future directions for standardization and improved clinical relevance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Facts

-

Conventional murine models lack the human cytokine support required for efficient engraftment and differentiation of MDS stem and progenitor cells.

-

Cytokine-humanized strains support improved multilineage hematopoiesis but show limitations in long-term stability and lineage-specific maturation.

-

There is no current murine model representative for MDS that fully copies the complex human bone marrow environment or immune system.

Open questions

-

How accurately do current humanized models reflect the sequential acquisition of mutations and clonal evolution in MDS?

-

Can preclinical models be standardized for therapeutic evaluation to improve reproducibility and inter-study comparability?

-

What are the optimal conditions (mouse strain, cytokine profile, preconditioning) for stable and representative engraftment of MDS?

-

What role do underrepresented mutations (e.g., BCOR, STAG2) play in disease progression and therapy response, and how can these be integrated into future models?

Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous group of clonal hematopoietic bone marrow disorders characterized by abnormal hematopoiesis and the presence of dysplasia in one or more blood cell lineages, which have the potential to progress to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Complex and less predictive interactions between genetic, epigenetic and microenvironmental factors contribute to the pathogenesis of MDS, making the development of animal models more challenging compared to AML, which is a more aggressive and well-defined disease [1]. The absence of sufficiently reliable MDS animal models has delayed the advancement of therapies. However, recent efforts have led to the improvement of more dependable and efficient animal models that better capitulate MDS providing a more optimistic perspective for future progress.

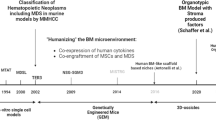

Early efforts to model hematologic malignancies focused on subcutaneous implantation of patient-derived AML cells into immunodeficient mice, as documented by early studies [2]. Functional engraftment of MDS cells in immunodeficient mice was only demonstrated in the early 2000s [3, 4]. However, these models had low efficiency and incomplete clonal representation. Later advancements like systemic engraftment via tail vein injections and the use of more immunocompromised strains (e.g., NSG, NOG mice lacking functional B, T, NK cells), improved hematological diseases representation in vivo [5].

Another breakthrough was the introduction of co-transplantation of MSCs with hematopoietic cells from MDS patients into immunocompromised mice which has shown mixed results, but while some studies report stable engraftment of mutations like RUNX1 and SF3B1, others find MSCs provide only temporary support [6,7,8,9]. Also, preconditioning strategies, such as low-dose radiation or macrophage-depleting drugs like clodronate, help improve these models, particularly for low-risk MDS cases [10].

Humanized mouse models have revolutionized MDS research by facilitating the study of clonal dynamics and bone marrow microenvironment (BME) interactions in vivo. While early models relied on immunodeficient strains like NSG (NOD/SCID-γ) for basic engraftment, modern approaches such as cytokine-humanized mice (e.g., MISTRG) and genetically engineered HSPCs have improved MDS representation. For example, MISTRG mice, which express human M-CSF, IL-3, GM-CSF, SIRPα, and thrombopoietin, has substantial myeloid engraftment ( > 80% CD33+ cells) and preserve patient-specific mutations, exceeding traditional NSG models [6, 11,12,13].

Spontaneous MDS have the advantage of increased clonal heterogeneity, but generating such models require maintaining approximately 30,000 mice for 20 months, as reported by Zhou et al., making large-scale or long-term studies financially impractical [14].

Mutations in MDS and their representation in preclinical mouse models

MDS are caused by various somatic mutations that disrupt critical regulatory processes controlling hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal, differentiation, and apoptosis pathways [15]. High-throughput sequencing studies have shown recurrent mutations in genes involved in RNA splicing (SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1, ZRSR2), epigenetic regulation (TET2, DNMT3A, ASXL1, EZH2), transcriptional control (RUNX1, TP53), and signal transduction (RAS pathway genes, CBL, JAK2) [16,17,18,19,20,21]. The functional impact of these mutations varies, some of them promote early clonal hematopoiesis, and others facilitate disease progression and leukemic transformation.

For example, SF3B1 mutations induce impaired erythropoiesis and the production of ring sideroblasts, while TP53 loss-of-function mutations correlate with genomic instability and resistance to therapy [22]. Table 1 provides an overview of MDS-associated mutations (selected based on their high frequency), their pathogenic mechanisms, occurrence in MDS patients, representative preclinical models, and associated limitations.

Expanding long-term HSCs in vitro is challenging, and the availability of MDS cell lines is limited, highlighting the necessity for in vivo models that accurately reproduce primary MDS [23]. The extent to which preclinical models replicate human MDS is an important consideration, particularly regarding hematopoietic microenvironment interactions and immunological regulation [24].

The molecular heterogeneity of MDS reinforces the need for model systems that can represent the human disease pathogenesis. So, genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) have been generated to incorporate specific driver mutations, and can offer insight into disease mechanisms in an immune-competent system. A summary of mutation-specific mouse models and their correspondence to clinical MDS subtypes is provided in Table 2. On the other hand, patient derived xenograft (PDX) models can accurately reproduce the biological characteristics of the disease and facilitate the analysis of primary MDS cells in a murine environment. In addition, PDX models are particularly valuable tools to investigate therapeutic responses. The specific relevance of these models depends on their capacity to maintain clonal hierarchy, differentiation biases, and responsiveness to therapeutic interventions [25]. Figure 1 illustrates three key strategies for developing mouse models of MDS.

The left column illustrates genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs), where MDS-related genetic modifications are introduced using transgenic, knock-in/knock-out, or inducible systems. The middle column represents cell line-derived xenografts (CDX), where mouse or human cell lines are transplanted into immunocompetent or immunodeficient mice, respectively. The right column depicts primary cell transplantation/humanized models, where primary human hematopoietic with or without stromal cells are transplanted into preconditioned mice to create a more physiologically relevant microenvironment for studying MDS. Created with BioRender.com.

Genetically engineered immunodeficient models

Foundational models: NSG and BRG mice

NOD/SCID/IL2rγ−/− (NSG) mice, characterized by the IL2rg null and Prkdcscid mutations, remain the gold standard for human HSC engraftment due to their T, B, and NK cell deficiencies [26]. Their NOD genetic background improves compatibility with human CD47-SIRPα interactions, reducing macrophage-mediated clearance of engrafted cells compared with BRG mice [27, 28]. This allows human HSC engraftment levels to reach 60% in bone marrow by 16 weeks post-transplantation [29].

However, a significant limitation of NSG mice is their limited support for myeloid engraftment and differentiation, which complicates the modeling of MDS that frequently include erythroid and megakaryocytic dysplasia. As a result, derivative strains like NSG-SGM3 and NOG-EXL were designed to express human cytokines including GM-CSF and IL-3 in order improve myeloid and erythroid differentiation [1].

CD3E humanized mice

While PDX models primarily focus on preserving tumor heterogeneity for cancer research, CD3E humanized mice provide a platform for detailed investigations into T cell receptor signaling and therapeutic antibody interactions. This model facilitates the study of T-cell interactions and responses to therapies targeting specific antigens, such as CD20 or CD19 [30].

CD3E humanized mice (e.g., BALBc-hCD3EDG) enable precise evaluation of T-cell-engaging therapies by preserving human CD3ε/δ/γ heterodimers critical for TCR signaling [31, 32]. This is particularly relevant to MDS, where immune dysregulation manifests as skewed regulatory T-cell (Treg) ratios and exhausted cytotoxic T cells [33, 34]. In CD3E models, anti-human thymocyte globulin (ATG) selectively depletes conventional T cells while sparing Tregs [34], recapitulating the immunosuppressive Treg dominance observed in significant number of MDS cases [35, 36].

A clinically relevant example is vibecotamab, a CD3–CD123 bispecific antibody, which achieved a 68% clinical benefit rate in MDS/CMML after failure of hypomethylating agents in a Phase II study [37]. In CD3E-humanized mouse models such as BALB/c-hCD3EDG, T-cell subpopulation distributions, including the CD4:CD8 ratio, are maintained at levels closely resembling wild-type mice, ensuring physiologically relevant immune responses [30].

To date, there is no direct mechanistic data to validate these models for MDS, but studies in analogous humanized and CD123-targeting systems show T-cell activation, IFN-γ release [38], and preferential targeting of CD123⁺ blasts over normal CD34⁺ progenitors [39]. These findings validate the model’s utility for studying checkpoint inhibitor responses and bispecific antibody efficacy in MDS-associated immune evasion.

CD3E humanized mice are developed by replacing the murine CD3E protein with its human version using gene targeting techniques. This modification allows T cells in these mice to effectively interact with human-specific antibodies, facilitating studies on T-cell activation and proliferation. These mice have normal thymic development and can be activated by crosslinking with anti-human CD3E antibodies, similar to wild-type T cells [40]. These models bind human CD3E antibodies and transduce the necessary signals for T-cell activation, making them particularly useful for screening anti-human CD3E antibodies and evaluating drugs that target the human CD3 signaling pathway [41]. Moreover, studies indicate that the distribution of lymphocyte subpopulations in CD3E humanized mice is aligned with wild-type mice, suggesting that introducing human CD3E does not affect overall immune cell functionality [30].

By enabling human-specific CD3E interactions, these models can be useful for testing immunotherapies, screening novel T cell-engaging and antibody therapies and investigating T cell-mediated immune responses.

Cytokine-humanized models

One important challenge in modeling MDS is cytokine dependency since murine cytokines show minimal cross-reactivity with human hematopoietic cells, limiting the efficiency of human hematopoiesis in patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models [42]. The changes in the microenvironmental interactions between murine and human hematopoietic systems can influence disease progression since mouse stromal and immunological components do not perfectly match the human bone marrow niche [43]. Also, genetic background contributes to variations in disease progression, as some mutations may have distinct functional effects in mice compared to human hematopoietic cells [44].

Cytokine-humanized mouse models integrate human cytokines to augment the proliferation of donor-derived human cells and the development of the immune system. In contrast to traditional models, these have distinct cytokine expression profiles that influence their capacity to support diverse hematopoietic lineages using factors such SCF, CSF-1, GM-CSF, IL-3, IL-6, IL-7, and IL-15 [45].

As summarized in Table 3, selecting an appropriate humanized mouse model depends on the specific research objectives and the hematopoietic lineage under investigation.

The differential expression of human cytokines in these strains demonstrates the importance of species-specific cytokine support in promoting efficient engraftment. Murine cytokines present suboptimal interactions with human hematopoietic cells, so there is the need to introduce human-specific cytokines that support the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of transplanted hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) [45].

This is particularly relevant in MISTRG and MITRG mice, where human TPO, IL-3, GM-CSF, G-CSF, and SCF collectively promote the expansion of both myeloid and erythroid lineages, making these models ideal for studies of MDS progression [46]. This combination improves the survival of human HSCs and facilitates the development of functional macrophages, granulocytes, and NK cells. This expression pattern makes MISTRG highly effective for studying disorders that involve both myeloid and erythroid lineages, including MDS [47].

Similarly, NSG-SGM3 mice, which express human IL-3, GM-CSF, and SCF, have demonstrated improved myeloid cell differentiation, making them useful for investigating hematopoietic malignancies [29]. Still, their utility is limited by issues such as severe anemia and graft exhaustion over time [48]. Moreover, studies show that NSG-SGM3 mice are incapable of supporting MDS grafts long-term, with 100% of low-risk and 75% of high-risk MDS xenografts progressively losing engraftment viability after 24 weeks. This reduction is associated with insufficient support for lineage-specific differentiation processes, especially the TPO-mediated maturation of megakaryocytes, which is absent in existing NSG-derived models [1, 49].

In contrast, as mentioned, MISTRG have an optimized cytokine expression that facilitates both myeloid and erythroid lineage differentiation, by incorporating human TPO, making this strain of mice highly suitable for studying MDS [50].

In 2024, a study introduced MISTRG6kitW41 (M6k) as an improved cytokine-humanized PDX model for MDS research. By incorporating the c-kit W41/W41 mutation, M6k improves HSC engraftment without the need of irradiation preconditioning, and outperforms conventional MISTRG models, particularly in erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation. At the molecular level, M6k preserves the genetic and transcriptomic profiles of patient-derived MDS samples and retains mutations such as SRSF2, U2AF1, TET2, RUNX1, IDH2, ASXL1. scRNA-seq analysis confirmed that CD34 + MDS cells in M6k mice closely showed a high similarity with the patient-derived equivalents. The model demonstrates stable huCD45+ and CD34+ engraftment in bone marrow and peripheral blood, supporting long-term disease simulation and replicating secondary AML progression. While NSG-SGM3 supports human hematopoiesis via transgenic cytokine expression, M6k enhances engraftment by impairing host stem cells through a c-kit mutation, promoting stable erythroid and megakaryocytic development [10].

The NOGW-EXL model represents an alternative to NSG-SGM3 for studies requiring sustained human hematopoiesis. Although not specifically developed for MDS, it can address some limitations of NSG-SGM3, such as anemia and graft exhaustion. This model carries a c-kit W41 mutation, which improves stem cell maintenance, and transgenically expresses human IL-3 and GM-CSF, supporting myeloid differentiation. Also, this mutation facilitates the engraftment of HSCs without requiring irradiation. Compared to NSG-SGM3, NOGW-EXL demonstrates improved long-term engraftment stability, particularly for granulocytes and megakaryocytes, making it a suitable alternative for preclinical research on MDS and related disorders [51, 52].

For example, in a study investigating alternative models to NSG-SGM3 for hematological malignancies, researchers demonstrated that NOG-EXL mice present a more controlled myeloid differentiation program, reducing excessive cytokine-driven activation. At molecular level, NOG-EXL mice presented more balanced activation of myeloid pathways, with reduced eosinophilic infiltrates and a lower incidence of mast cell hyperplasia compared to NSG-SGM3. Also, histological assessments showed that tissue infiltration by activated macrophages, which is prominent in NSG-SGM3, is significantly expressed in NOG-EXL, suggesting a more stable immune environment [48].

While cytokine-humanized models primarily support hematopoiesis, the Bone Marrow–Liver–Thymus (BLT) model is suitable for studying human immune function. BLT mice are generated by transplanting human fetal liver and thymus tissues under the kidney capsule of immunodeficient mice, followed by intravenous injection of CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells [53]. As a result, they develop a functional human adaptive immune system, with mature T and B cells, dendritic cells and macrophages. Their capacity to support proper thymic selection of human T cells makes them relevant for studies on immune responses, immune modulation in hematological diseases, and preclinical evaluation of immunotherapeutic strategies such as immune checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T cell therapy [54]. Compared to cytokine-humanized models, which primarily support specific hematopoietic lineages, BLT mice provide a more complex immune system model, allowing for investigations into host-tumor interactions and immune dysregulation in MDS [55].

Additionally, hIL-7 NOG mice have been studied for their role in improving T-cell development, direct evidence on their use in hematological disease modeling is limited. For example, transgenic expression of hIL-7 under murine regulatory elements in NSGW41 mice has been shown to improve human T cell expansion following CD34+ hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [56]. These findings indicate that incorporating hIL-7 into humanized models can create a more physiologically relevant system for studying immune cell interactions and evaluating immunotherapeutic approaches. Direct evidence on hIL-7 NOG mice is limited but studies have shown that transgenic expression of human IL-7 in NSGW41 mice promotes the expansion of functional human T cells following CD34+ hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [56, 57]. Moreover, the administration of human IL-7 in vivo leads to a sustained increase in T-cell numbers [58].

Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) in MDS research

MDS research has advanced through the use of PDX models, which are generated by transplanting primary human MDS cells, often mononuclear cells into immunodeficient mice. Unlike conventional murine models, such as GEMMs, PDXs preserve the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of the original disease, better reflecting its complexity [59].

Co-transplantation models: NSG, NSG-SGM3

Multiple research groups have attempted to co-engraft MSCs and MDS cells to promote leukemic stem cell myeloid differentiation and persistence. In one study, researchers co-transplanted 10⁴ CD34 + MDS-SCs with MSCs into gelatin-based porous scaffolds implanted in NSG-SGM3 immunodeficient mice, achieving long-term engraftment rates ranging from 0.2% to 86% hCD45+ cells, with 82% of cases reaching ≥20% hCD45+ cells after 12 to 18 weeks. The engrafted cells preserved key MDS-associated mutations, including SF3B1, DNMT3A, SRSF2, and TET2 [7].

In another study, transplanted 5 × 10⁵ CD34+ HSPCs and 1.5 × 10⁶ autologous MSCs from MDS patients into NSG mice using direct intramedullary injection, achieving 100% engraftment across patient samples. Human chimerism levels ranged from 59.7% to 0.0175% hCD45+ cells after 6 months, with secondary transplantation of 1 × 10⁵ CD34+ cells without MSCs maintaining 53.33% chimerism, demonstrating the long-term self-renewal capacity of MDS-initiating cells. Genetic analysis confirmed the stability of key mutations, including TP53, SF3B1, RUNX1, and KIT, across both primary and secondary recipients [9].

Some studies indicate improved engraftment with MSC co-injection, but others show minimal or no long-term advantage. Krevvata et al. examined the engraftment of MDS cells in NSG and NSG-SGM3 strains, showing that MSC co-injection provided a minimal influence on engraftment levels. MSCs offered temporary support to MDS cells, and the presence of MSCs did not substantially modify the clonal structure of the engrafted cells [8]. Rouault-Pierre et al. noted that MSC co-injection resulted in 100% engraftment in NSG and NSG-SGM3 mice but human chimerism levels showed considerable variability, spanning from 59.7% to 0.0175% hCD45+ cells after 6 months. The secondary transplantation of 1 × 10⁵ CD34+ cells without MSCs resulted in 53.33% chimerism, which indicates that MSCs are not critical for the maintenance of long-term hematopoiesis [6].

Preconditioning strategies for improved engraftment

Recent studies have optimized PDX models to improve the representation of low-risk MDS, characterized by low CD34+ blast counts and limited clonal dominance [11]. One important advancement in this field has been the optimization of preconditioning strategies to improve human hematopoietic engraftment in immunodeficient mice. A comparative summary of preconditioning strategies and their impact on engraftment efficiency across commonly used mouse strains is presented in Table 4. Traditionally, sublethal irradiation with doses varying from 200–375 cGy has been used to suppress murine hematopoiesis, creating space for transplanted human MDS cells [60,61,62]. In some cases, irradiation alone has been insufficient to achieve optimal engraftment, requiring the implementation of alternative or complementary methodologies.

To address the challenge of low-risk MDS modeling, Teodorescu et al. used NSG-S mice preconditioned with clodronate liposomes and low-dose radiation to model low-risk MDS, improving engraftment efficiency. Clodronate liposomes, administered intraperitoneally at 100 µL per animal 2 days before irradiation, depleted murine macrophages by up to 97% in bone marrow and over 99% in spleen, inhibiting human erythroid precursor clearance. Before intravenous transplantation of human CD34+ cells, mice received 2 Gy radiation on day 0 to inhibit residual mouse hematopoiesis. This method effectively preserved the genetic profile of low-risk MDS, including mutations such as SF3B1, ZRSR2, and ASXL1, while supporting long-term hematopoiesis [11].

Another strategy is the use of ultra-low dose irradiation (0.5 Gy) as a preconditioning method. A recent study, showed that this approach facilitates engraftment while preserving the bone marrow microenvironment. The low dose did not compromise the vascular barrier (increase vascular permeability). In general, an irradiation threshold of 2 Gy has been reported to induce secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators, degradation of endothelial junctions, and an increase in vascular permeability and allowed long-term engraftment compared to non-conditioned host animals [63].

Antypiuk et al. developed an alternative preconditioning method by targeting iron metabolism in CD45.2 + MDS mice. Using TMPRSS6 silencing via GalNAc-conjugated siRNA in CD45.2 + MDS mice they increased hepcidin levels, reducing conditioning-induced Non-Transferrin Bound Iron and improving donor HSPC engraftment after BMT. Their results suggest that iron restriction improved transplantation outcomes by reducing chemotherapy-induced toxicity [64].

Another option is busulfan, a chemotherapeutic drug that eliminates host hematopoietic cells without requiring radiation exposure. Research has shown that administering busulfan at 20 mg/kg intraperitoneally may produce similar levels of hematopoietic suppression in mice [65, 66]. However, busulfan can induce significant toxic effects. Doses ≥25 mg/kg/day in NSG mice can result in increased severity of clinical signs and mortalities between Days 1 and 25 [67]. Also, busulfan can also induce toxic effects on the epididymis and cause long-term morphological damage to sperm, potentially leading to permanent sterilization [68].

Figure 2 provides a comparative overview of commonly used immunodeficient mouse models in MDS research, including their cytokine expression profiles, lineage support capacities, engraftment sites, and key experimental features.

Five immunodeficient mouse models commonly utilized for MDS research (NSG, NSGS-SGM3, MISTRG, MISTRG KitW41, and NOG-EXL) are presented. Each mouse model is depicted with key human cytokines they express, lineage support capacity (myeloid, erythroid, megakaryocytic, and lymphoid lineages), and sites of human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) engraftment. Color and size-coded circles illustrate the extent of lineage differentiation support provided by each model, ranging from minimal to very high. Additionally, the figure summarizes key characteristics and commonly associated applications of each model (clipboard symbol), as well as their advantages in supporting human hematopoiesis (checkmark symbol) and their experimental limitations (exclamation mark symbol). Created with BioRender.com.

Alternative genetically diverse models

In addition to humanized models, genetically diverse mouse strains have been also developed to investigate the impact of host genetics on MDS pathogenesis and disease heterogeneity. To address genetic diversity limitations in mouse modeling, The Collaborative Cross (CC) mouse population has been developed, which captures over 90% of the genetic variation in mice, and has been proposed as an alternative for more representative disease modeling [69]. Compared to traditional inbred strains, CC mice facilitate the study of genetic factors that influence disease susceptibility, clonal evolution and treatment response variability [70]. Among CC strains, the JUN mouse strain has been identified as a candidate due to its spontaneous development of MDS-like symptoms, including cytopenia and abnormal differentiation of bone marrow progenitor cells. These strains are important for investigating host-specific genetic contributions to MDS, but their translational utility is limited, as murine hematopoietic and immune systems differ significantly from human counterparts. While CC and JUN mice allow for the study of genetic susceptibility and environmental influences in MDS, humanized models are the primary platform for translational research, particularly in drug development and immunotherapy [71].

Preclinical modeling using cell line-derived xenografts

Most MDS cell lines do not successfully develop stable xenografts due to their dependency on the microenvironment, and insufficient murine cytokine support. Compared to AML cell lines, MDS cells have a limited proliferative capacity and require exogenous cytokines, like IL-3, GM-CSF, and SCF, which is limiting in vivo studies [8]. For example, MDS-L has two subclones, MDS-L-2007 and MDS-LGF, each with distinct IL-3 dependency and proliferation capacity [72]. MDS-LGF proliferates with minimal IL-3 (1 ng/mL) and achieves higher engraftment rates, while MDS-L-2007 needs higher supplementation of IL-3 (100 ng/mL), which reduces the in vivo applicability [8].

Several studies have classified MDS cell lines into three distinct groups: false/non-malignant cell lines, malignant cell lines in the leukemic phase and valid MDS cell lines [1, 23].

As summarized in Table 5, only a subset of characterized MDS cell lines including M-TAT, MDS92, TER-3, and MDS-L serve as standardized experimental models for studying disease pathogenesis and therapeutic responses. These models have been validated through foundational studies, which demonstrate their functional attributes and genetic profiles, confirming their relevance in preclinical research.

Diagnostic alignment: progress and pitfalls

The diagnosis of MDS in animal models requires criteria that balance translational relevance to human disease with species-specific biological differences. The Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium (MMHCC) established diagnostic guidelines to standardize the classification of murine hematopoietic neoplasms, addressing inconsistencies in preclinical MDS research. This system categorizes nonlymphoid hematopoietic neoplasms into four groups: nonlymphoid leukemias, hematopoietic sarcomas, myeloid dysplasias, and myeloid proliferations [14].

According to this system, the diagnosis of nonlymphoid leukemia requires the presence of ≥20% immature forms or blasts in the bone marrow or spleen. In contrast, myeloid dysplasias are characterized by cytopenias and abnormal differentiation, with the exclusion of cases exhibiting ≥20% blasts. These cytopenias include neutropenia, anemia, or thrombocytopenia without leukocytosis or erythrocytosis being present. Morphological abnormalities can further support this diagnosis. Dyserythropoiesis is recognized by megaloblastic changes, fragmented nuclei, or ringed sideroblasts, while dysgranulopoiesis is characterized by atypical nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation. Dysplastic megakaryocytes are marked by multiple distinct nuclei or micromegakaryocytes [73, 74]. Moreover, molecular tests could help to confirm the existence of a monoclonal population [75].

While these criteria reflect human diagnostic parameters, including cytopenias, dysplasia, and blast thresholds, they do not fully capture species-specific differences that limit translational accuracy. For example, in humans, bone marrow fat (BMF) constitutes ~70% of marrow volume in adults and regulates HSC behavior through adipocyte-derived factors like leptin and adiponectin. With aging, BMF expansion correlates with reduced hematopoiesis which can drive MDS progression [14].

In contrast, murine marrow contains <5% BMF, and they may fail to capture for example adipokine-mediated inflammation, like elevated TNF-α and IL-6 which are representative for human MDS [43].

Also, while genetically engineered models can replicate individual mutations like TP53 or SF3B1, they can fail to capture the clonal complexity of human MDS, where the sequential accumulation of mutations such as TET2, ASXL1, and splicing factors drives disease progression [14].

In terms of validation practices, studies show that only 12% of MDS mouse studies report randomization, while less than 5% implement blinding. This aspect could introduce bias and reduce the relevance of the results and therefore limiting the translational applicability [76]. To improve the protocol standardization and crosslab reproducibility, the preregistration of preclinical protocols in platforms like preclinical.eu or animalstudyregistry.org could reduce selective reporting [77].

Emerging trends and future directions

The development of humanized mouse models has transformed and expanded our capacity to study MDS, however critical limitations remain to be addressed, limiting their ability to fully reproduce the complexity of human disease.

The Minimal Information for Standardization of Humanized Mice (MISHUM) initiative points out the need for community-driven, standardized reporting guidelines that improve quality and reproducibility in these models; still these frameworks have not been systematically implemented in MDS research due to persistent challenges in protocol alignment and data standardization [78].

Other guidelines like the ARRIVE 2.0 [79] and PREPARE guidelines [80] provide foundational principles for transparent reporting and precise experimental design, but their application to MDS-specific studies is inconsistent. Although standardization of MDS mouse models is achievable in principle, its practical implementation remains complex due to the need for precise, shared databases and consensus on experimental design, which are currently lacking in most research settings. As discussed in recent reviews, the heterogeneous nature of MDS and the variability in model systems, and insufficient reporting of critical parameters present significant challenges to the development of universally accepted standards [78].

In an overview of 31 systematic reviews, Hirst et al. reported that only 29% of animal studies using models such as mice documented randomization, 15% reported allocation concealment, and 35% reported blinded outcome assessment. Lack of randomization was significantly associated with exaggerated effect sizes. These results indicate substantial methodological deficiencies in animal research, which undermine the reliability and translational relevance of murine models, including those applied in MDS [81].

While cytokine supplementation (e.g., SCF, GM-CSF, IL-3) and niche-specific conditioning (e.g., c-kit targeting) have improved human hematopoietic cell engraftment in murine models, they still fail to replicate the full complexity of BME [82]. A major challenge is the rapid clearance of mature human blood cells, like platelets and erythrocytes, by the host immune system. Current strategies, like anti-CD117 antibodies or transient immune suppression, offer only partial solutions. Advancing humanized models is important to simulate better MDS and improve long-term engraftment [83].

Most current MDS research is focused on high-frequency mutations (SF3B1, TP53) while omitting rarer variants that have distinct clinical impacts. SF3B1 mutations, present in 31% of MDS cases, are studied intensively due to their association with favorable outcomes in ring sideroblast subtypes [84]. Similarly, TP53 mutations ( ~ 25% prevalence) are extensively studied for their link to aggressive disease and treatment resistance [85]. While mouse models have advanced our understanding of common MDS-associated mutations like SF3B1 and TP53, the field requires models that capture rare but clinically significant variants such as BCOR and STAG2 [86].

While advanced murine models of MDS have started to cover immune evasion strategies, like Treg expansion or CD8 + T-cell exhaustion, there is a gap in understanding the causality and mutation-specific dynamics [87, 88].

For example, studies on transgenic TRAF6-overexpressing mice show that MDS HSPCs can adapt to inflammation by upregulating A20. This favors the survival of MDS HSPCs while normal HSPCs are affected by inflammatory stress [89]. However, these murine models are mostly used to study late stages disease, like NUP98-HOXD13 or S100A9 transgenic mice, which replicate advanced MDS phenotype, but offer insights about early clonal competition or pre-malignant stages [90, 91].

The next generation of MDS models should move beyond studying high-frequency mutations and late-stage disease to incorporate the full spectrum of genetic, immune, and stromal interactions. We anticipate that these improvements would ultimately lead to more efficient preclinical drug development and better personalized treatment strategies.

References

Mina A, Pavletic S, Aplan PD. The evolution of preclinical models for myelodysplastic neoplasms. Leukemia. 2024;38:683–91.

Franks CR, Bishop D, Balkwill FR, Oliver RT, Spector WG. Growth of acute myeloid leukaemia as discrete subcutaneous tumours in immune-deprived mice. Br J Cancer. 1977;35:697–700.

Nilsson L, Åstrand-Grundström I, Anderson K, Arvidsson I, Hokland P, Bryder D, et al. Involvement and functional impairment of the CD34 + CD38−Thy-1+ hematopoietic stem cell pool in myelodysplastic syndromes with trisomy 8. Blood. 2002;100:259–67.

Kerbauy DMB, Lesnikov V, Torok-Storb B, Bryant E, Deeg HJ. Engraftment of distinct clonal MDS-derived hematopoietic precursors in NOD/SCID-β2-microglobulin-deficient mice after intramedullary transplantation of hematopoietic and stromal cells. Blood. 2004;104:2202–3.

Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645–8.

Rouault-Pierre K, Mian SA, Goulard M, Abarrategi A, Di Tulio A, Smith AE, et al. Preclinical modeling of myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2017;31:2702–8.

Mian SA, Abarrategi A, Kong KL, Rouault-Pierre K, Wood H, Oedekoven CA, et al. Ectopic humanized mesenchymal niche in mice enables robust engraftment of myelodysplastic stem cells. Blood Cancer Discov. 2021;2:135–45.

Krevvata M, Shan X, Zhou C, Dos Santos C, Habineza Ndikuyeze G, Secreto A, et al. Cytokines increase engraftment of human acute myeloid leukemia cells in immunocompromised mice but not engraftment of human myelodysplastic syndrome cells. Haematologica. 2018;103:959–71.

Meunier M, Dussiau C, Mauz N, Alary AS, Lefebvre C, Szymanski G, et al. Molecular dissection of engraftment in a xenograft model of myelodysplastic syndromes. Oncotarget. 2018;9:14993–5000.

Teodorescu P, Pasca S, Choi I, Shams C, Dalton WB, Gondek LP, et al. An accessible patient-derived xenograft model of low-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Haematologica. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2023.282967.

Coriu D, Stancioaica M-C. Moving low risk myelodysplastic syndromes from human to mice: is it truly that simple? Haematologica. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2023.283652.

Villaume MT, Savona MR. Pathogenesis and inflammaging in myelodysplastic syndrome. Haematologica. 2024. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2023.284944.

Chen B, Liu H, Liu Z, Yang F. Benefits and limitations of humanized mouse models for human red blood cell-related disease research. Front Hematol. 2023;1. https://doi.org/10.3389/frhem.2022.1062705.

Zhou T, Kinney MC, Scott LM, Zinkel SS, Rebel VI. Revisiting the case for genetically engineered mouse models in human myelodysplastic syndrome research. Blood. 2015;126:1057–68.

Hosono N. Genetic abnormalities and pathophysiology of MDS. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24:885–92.

Caponetti GC, Bagg A. Mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes: core abnormalities and CHIPping away at the edges. Int J Lab Hematol. 2020;42:671–84.

Kontandreopoulou C-N, Kalopisis K, Viniou N-A, Diamantopoulos P. The genetics of myelodysplastic syndromes and the opportunities for tailored treatments. Front Oncol. 2022;12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.989483.

Cook MR, Karp JE, Lai C. The spectrum of genetic mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome: should we update prognostication?. EJHaem. 2022;3:301–13.

Malcovati L, Hellström-Lindberg E, Bowen D, Adès L, Cermak J, del Cañizo C, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary myelodysplastic syndromes in adults: recommendations from the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2013;122:2943–64.

Bejar R, Stevenson K, Abdel-Wahab O, Galili N, Nilsson B, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2496–506.

Haferlach T, Nagata Y, Grossmann V, Okuno Y, Bacher U, Nagae G, et al. Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2014;28:241–7.

Jiang M, Chen M, Liu Q, Jin Z, Yang X, Zhang W. SF3B1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes: a potential therapeutic target for modulating the entire disease process. Front Oncol. 2023;13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1116438.

Drexler HG, Dirks WG, MacLeod RAF. Many are called MDS cell lines: one is chosen. Leuk Res. 2009;33:1011–6.

Ogawa S. Genetics of MDS. Blood. 2019;133:1049–59.

Liu W, Teodorescu P, Halene S, Ghiaur G. The coming of age of preclinical models of MDS. Front Oncol. 2022;12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.815037.

Hasan T, Pasala AR, Hassan D, Hanotaux J, Allan DS, Maganti HB. Homing and engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells following transplantation: a pre-clinical perspective. Current Oncol. 2024;31:603–16.

Li F, Cowley DO, Banner D, Holle E, Zhang L, Su L. Efficient genetic manipulation of the NOD-Rag1-/-IL2RgammaC-null mouse by combining in vitro fertilization and CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5290.

Zhao Y, Liu P, Xin Z, Shi C, Bai Y, Sun X, et al. Biological characteristics of severe combined immunodeficient mice produced by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Rag2 and IL2rg mutation. Front Genet. 2019;10:401.

Wunderlich M, Chou F-S, Sexton C, Presicce P, Chougnet CA, Aliberti J, et al. Improved multilineage human hematopoietic reconstitution and function in NSGS mice. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0209034.

Wang L, Leach V, Muthusamy N, Byrd J, Long M. A CD3 humanized mouse model unmasked unique features of T-cell responses to bispecific antibody treatment. Blood Adv. 2024;8:470–81.

Yang X, Ju C, Zhang M, Zhao J. Abstract 5195: Humanized CD3E,D,G mice: an ideal model for efficacy study of CD3-bispecific antibodies. Cancer Res. 2022;82:5195.

Wu Y, Yu X-Z. Modelling CAR-T therapy in humanized mice. EBioMedicine. 2019;40:25–26.

Liu S, Joshi K, Zhang L, Li W, Mack R, Runde A, et al. Caspase 8 deletion causes infection/inflammation-induced bone marrow failure and MDS-like disease in mice. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15:278.

Buszko M, Cardini B, Oberhuber R, Oberhuber L, Jakic B, Beierfuss A, et al. Differential depletion of total T cells and regulatory T cells and prolonged allotransplant survival in CD3Ɛ humanized mice treated with polyclonal anti human thymocyte globulin. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0173088.

Costantini B, Kordasti SY, Kulasekararaj AG, Jiang J, Seidl T, Abellan PP, et al. The effects of 5-azacytidine on the function and number of regulatory T cells and T-effectors in myelodysplastic syndrome. Haematologica. 2013;98:1196–205.

Bontkes HJ, Alhan C, Eeltink C, Westers TM, Ossenkoppele GJ, Van de Loosdrecht AA. Immunomodulatory effects of azacitidine treatment in high risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2010;116:1860.

Nguyen D, Ravandi F, Wang SA, Jorgensen JL, WANG W, Loghavi S, et al. Updated results from a phase II study of vibecotamab, a CD3-CD123 bispecific T-cell engaging antibody, for MDS or CMML after hypomethylating failure and in MRD-positive AML. Blood. 2024;144:1007.

Uy GL, Godwin J, Rettig MP, Vey N, Foster M, Arellano ML, et al. Preliminary results of a phase 1 study of flotetuzumab, a CD123 x CD3 Bispecific Dart® protein, in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2017;130:637.

Barwe SP, Kisielewski A, Bonvini E, Muth J, Davidson-Moncada J, Kolb EA, et al. Efficacy of flotetuzumab in combination with cytarabine in patient-derived xenograft models of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1333.

Zhang R, Zhang J, Zhou X, Zhao A, Yu C. The establishment and application of CD3E humanized mice in immunotherapy. Exp Anim. 2022;71:22–0012.

Itani HA, McMaster WG, Saleh MA, Nazarewicz RR, Mikolajczyk TP, Kaszuba AM, et al. Activation of human T cells in hypertension. Hypertension. 2016;68:123–32.

Coats JS, Baez I, Stoian C, Milford T-AM, Zhang X, Francis OL, et al. Expression of exogenous cytokine in patient-derived xenografts via injection with a cytokine-transduced stromal cell line. J Vis Exp. 2017. https://doi.org/10.3791/55384.

Wang J, Erlacher M, Fernandez-Orth J. The role of inflammation in hematopoiesis and bone marrow failure: What can we learn from mouse models? Front Immunol. 2022;13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.951937.

Saito Y, Shultz LD, Ishikawa F. Understanding normal and malignant human hematopoiesis using next-generation humanized mice. Trends Immunol. 2020;41:706–20.

Allen TM, Brehm MA, Bridges S, Ferguson S, Kumar P, Mirochnitchenko O, et al. Humanized immune system mouse models: progress, challenges and opportunities. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:770–4.

Song Y, Rongvaux A, Taylor A, Jiang T, Tebaldi T, Balasubramanian K, et al. A highly efficient and faithful MDS patient-derived xenotransplantation model for pre-clinical studies. Nat Commun. 2019;10:366.

Ito R, Takahashi T, Katano I, Ito M. Current advances in humanized mouse models. Cell Mol Immunol. 2012;9:208–14.

Willis E, Verrelle J, Banerjee E, Assenmacher C-A, Tarrant JC, Skuli N, et al. Humanization with CD34-positive hematopoietic stem cells in NOG-EXL mice results in improved long-term survival and less severe myeloid cell hyperactivation phenotype relative to NSG-SGM3 mice. Vet Pathol. 2024;61:664–74.

Griessinger E, Andreeff M. NSG-S mice for acute myeloid leukemia, yes. For myelodysplastic syndrome, no. Haematologica. 2018;103:921–3.

Gutierrez-Barbosa H, Medina-Moreno S, Perdomo-Celis F, Davis H, Coronel-Ruiz C, Zapata JC, et al. A comparison of lymphoid and myeloid cells derived from human hematopoietic stem cells xenografted into NOD-derived mouse strains. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1548.

Ito R, Ohno Y, Mu Y, Ka Y, Ito S, Emi-Sugie M, et al. Improvement of multilineage hematopoiesis in hematopoietic stem cell-transferred c-kit mutant NOG-EXL humanized mice. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024;15:182.

Maser I-P, Hoves S, Bayer C, Heidkamp G, Nimmerjahn F, Eckmann J, et al. The tumor milieu promotes functional human tumor-resident plasmacytoid dendritic cells in humanized mouse models. Front Immunol. 2020;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.02082.

Smith DJ, Lin LJ, Moon H, Pham AT, Wang X, Liu S, et al. Propagating humanized BLT mice for the study of human immunology and immunotherapy. Stem Cells Dev. 2016;25:1863–73.

Aryee K-E, Shultz LD, Brehm MA. Immunodeficient mouse model for human hematopoietic stem cell engraftment and immune system development. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;118:267–78.

Yan H, Semple KM, Gonzaléz CM, Howard KE. Bone marrow-liver-thymus (BLT) immune humanized mice as a model to predict cytokine release syndrome. Translational Res. 2019;210:43–56.

Coppin E, Sundarasetty BS, Rahmig S, Blume J, Verheyden NA, Bahlmann F, et al. Enhanced differentiation of functional human T cells in NSGW41 mice with tissue-specific expression of human interleukin-7. Leukemia. 2021;35:3561–7.

Chuprin J, Buettner H, Seedhom MO, Greiner DL, Keck JG, Ishikawa F, et al. Humanized mouse models for immuno-oncology research. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:192–206.

Kim S, Lee SW, Koh J-Y, Choi D, Heo M, Chung J-Y, et al. A single administration of hIL-7-hyFc induces long-lasting T-cell expansion with maintained effector functions. Blood Adv. 2022;6:6093–107.

Tian H, Lyu Y, Yang Y-G, Hu Z. Humanized rodent models for cancer research. Front Oncol. 2020;10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.01696.

van der Loo JCM, Hanenberg H, Cooper RJ, Luo F-Y, Lazaridis EN, Williams DA. Nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mouse as a model system to study the engraftment and mobilization of human peripheral blood stem cells. Blood. 1998;92:2556–70.

Andrade J, Ge S, Symbatyan G, Rosol MS, Olch AJ, Crooks GM. Effects of sublethal irradiation on patterns of engraftment after murine bone marrow transplantation. Biology Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:608–19.

Zhang Q, Rydström A, Hidalgo I, Cammenga J, Nilsson AR. Medium-dose irradiation impairs long-term hematopoietic stem cell functionality and hematopoietic recovery to cytotoxic stress. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.10.29.620607.

Lee K, Dissanayake W, MacLiesh M, Hong C-L, Yin Z, Kawano Y, et al. Ultralow-dose irradiation enables engraftment and intravital tracking of disease initiating niches in clonal hematopoiesis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:20486.

Antypiuk A, Martinez A, Schaeper U, Platzbecker U, Vinchi F. Myelodysplastic syndromes benefit from iron-restricted bone marrow transplant in preclinical mouse model. Blood. 2023;142:2462.

Montecino-Rodriguez E, Dorshkind K. Use of busulfan to condition mice for bone marrow transplantation. STAR Protoc. 2020;1:100159.

Garcia-Perez L, van Roon L, Schilham MW, Lankester AC, Pike-Overzet K, Staal FJT. Combining mobilizing agents with busulfan to reduce chemotherapy-based conditioning for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cells. 2021;10. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10051077.

Ballesteros C, Wong K, Abrahim MA, Li C, Authier S. Model characterization: total body irradiation or busulfan for conditioning in human cell therapy toxicology and tumorigenicity studies using NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull (NSG) mice. Int J Toxicol. 2023;42:219–31.

Bucci LR, Meistrich ML. Effects of busulfan on murine spermatogenesis: cytotoxicity, sterility, sperm abnormalities, and dominant lethal mutations. Mutat Res. 1987;176:259–68.

Threadgill DW, Miller DR, Churchill GA, de Villena FP-M. The collaborative cross: a recombinant inbred mouse population for the systems genetic era. ILAR J. 2011;52:24–31.

Churchill GA, Airey DC, Allayee H, Angel JM, Attie AD, Beatty J, et al. The Collaborative Cross, a community resource for the genetic analysis of complex traits. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1133–7.

Li W, Cao L, Li M, Yang X, Zhang W, Song Z, et al. Novel spontaneous myelodysplastic syndrome mouse model. Animal Model Exp Med. 2021;4:169–80.

Shafiee S, Gelebart P, Popa M, Hellesøy M, Hovland R, Brendsdal Forthun R, et al. Preclinical characterisation and development of a novel myelodysplastic syndrome-derived cell line. Br J Haematol. 2021;193:415–9.

Wegrzyn J, Lam JC, Karsan A. Mouse models of myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Res. 2011;35:853–62.

Li W, Li M, Yang X, Zhang W, Cao L, Gao R. Summary of animal models of myelodysplastic syndrome. Animal Model Exp Med. 2021;4:71–76.

Kogan SC, Ward JM, Anver MR, Berman JJ, Brayton C, Cardiff RD, et al. Bethesda proposals for classification of nonlymphoid hematopoietic neoplasms in mice. Blood. 2002;100:238–45.

Herrmann K, Jayne K, editors. Animal experimentation: working towards a paradigm change. Brill Publishing House, Leiden (The Netherlands) and Boston (USA); 2019. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004391192.

Huang W, Percie du Sert N, Vollert J, Rice ASC. General principles of preclinical study design. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2020;257:55–69.

Stripecke R, Münz C, Schuringa JJ, Bissig K-D, Soper B, Meeham T, et al. Innovations, challenges, and minimal information for standardization of humanized mice. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12:e8662.

Hair K, Macleod MR, Sena ES. A randomised controlled trial of an intervention to improve compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (IICARus). Res Integr Peer Rev. 2019;4:12.

Smith AJ, Clutton RE, Lilley E, Hansen KEA, Brattelid T. PREPARE: guidelines for planning animal research and testing. Lab Anim. 2018;52:135–41.

Hirst JA, Howick J, Aronson JK, Roberts N, Perera R, Koshiaris C, et al. The need for randomization in animal trials: an overview of systematic reviews. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e98856.

Baassiri A, Maziarz J, Blackburn HN, Maul-Newby H, VanOudenhove J, Zhang X, et al. MISTRG6kitW41: enhanced engraftment in a cytokine humanized patient-derived xenotransplantation mouse model. Blood. 2024;144:1815.

Dal Collo G, van Hoven-Beijen A, He Y, Muller YM, Wang Y, Zhao J, et al. Novel anti-CD117 antibodies for rapid and efficient hematopoietic stem cell depletion and safe bone marrow conditioning. Blood. 2022;140:4496–7.

Huber S, Haferlach T, Meggendorfer M, Hutter S, Hoermann G, Baer C, et al. SF3B1 mutated MDS: Blast count, genetic co-abnormalities and their impact on classification and prognosis. Leukemia. 2022;36:2894–902.

Zhang L, Chen K, Li Y, Chen Q, Shi W, Ji T, et al. Clinical outcomes and characteristics of patients with TP53 -mutated myelodysplastic syndromes. Hematology. 2023;28. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078454.2023.2181773.

Baranwal A, Gurney M, Basmaci R, Katamesh B, He R, Viswanatha DS, et al. Genetic landscape and clinical outcomes of patients with BCOR mutated myeloid neoplasms. Haematologica. 2024. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2023.284185.

Barakos GP, Hatzimichael E. Microenvironmental features driving immune evasion in myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia. Diseases. 2022;10:33.

Tasis A, Spyropoulos T, Mitroulis I. The emerging role of CD8 + T cells in shaping treatment outcomes of patients with MDS and AML. Cancers. 2025;17:749.

Muto, Walker T, Choi CS, Hueneman K, Smith MA K, Gul Z, et al. Adaptive response to inflammation contributes to sustained myelopoiesis and confers a competitive advantage in myelodysplastic syndrome HSCs. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:535–45.

Chen X, Eksioglu EA, Zhou J, Zhang L, Djeu J, Fortenbery N, et al. Induction of myelodysplasia by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Clin Investig. 2013;123:4595–611.

Lin Y-W, Slape C, Zhang Z, Aplan PD. NUP98-HOXD13 transgenic mice develop a highly penetrant, severe myelodysplastic syndrome that progresses to acute leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:287–95.

Kanagal-Shamanna R, Montalban-Bravo G, Sasaki K, Darbaniyan F, Jabbour E, Bueso-Ramos C, et al. Only SF3B1 mutation involving K700E independently predicts overall survival in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer. 2021;127:3552–65.

Mupo A, Seiler M, Sathiaseelan V, Pance A, Yang Y, Agrawal AA, et al. Hemopoietic-specific Sf3b1-K700E knock-in mice display the splicing defect seen in human MDS but develop anemia without ring sideroblasts. Leukemia. 2017;31:720–7.

Côme C, Balhuizen A, Bonnet D, Porse BT. Myelodysplastic syndrome patient-derived xenografts: from no options to many. Haematologica. 2020;105:864–9.

Liang Y, Tebaldi T, Rejeski K, Joshi P, Stefani G, Taylor A, et al. SRSF2 mutations drive oncogenesis by activating a global program of aberrant alternative splicing in hematopoietic cells. Leukemia. 2018;32:2659–71.

Wu S-J, Kuo Y-Y, Hou H-A, Li L-Y, Tseng M-H, Huang C-F, et al. The clinical implication of SRSF2 mutation in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and its stability during disease evolution. Blood. 2012;120:3106–11.

Arbab Jafari P, Ayatollahi H, Sadeghi R, Sheikhi M, Asghari A. Prognostic significance of SRSF2 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: a meta-analysis. Hematology. 2018;23:778–84.

Garcia-Manero G. Myelodysplastic syndromes: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2023;98:1307–25.

Velasco-Hernandez T, Säwén P, Bryder D, Cammenga J. Potential pitfalls of the Mx1-Cre system: implications for experimental modeling of normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Stem Cell Rep. 2016;7:11–18.

Kim E, Ilagan JO, Liang Y, Daubner GM, Lee SC-W, Ramakrishnan A, et al. SRSF2 mutations contribute to myelodysplasia by mutant-specific effects on exon recognition. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:617–30.

Niparuck P, Police P, Noikongdee P, Siriputtanapong K, Limsuwanachot N, Rerkamnuaychoke B, et al. TP53 mutation in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Diagn Pathol. 2021;16:100.

Jiang Y, Gao S-J, Soubise B, Douet-Guilbert N, Liu Z-L, Troadec M-B. TP53 in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancers. 2021;13:5392.

Hanel W, Marchenko N, Xu S, Xiaofeng Yu S, Weng W, Moll U. Two hot spot mutant p53 mouse models display differential gain of function in tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:898–909.

Sato H, Wheat JC, Steidl U, Ito K. DNMT3A and TET2 in the pre-leukemic phase of hematopoietic disorders. Front Oncol. 2016;6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2016.00187.

Mayle A, Yang L, Rodriguez B, Zhou T, Chang E, Curry CV, et al. Dnmt3a loss predisposes murine hematopoietic stem cells to malignant transformation. Blood. 2015;125:629–38.

Venugopal K, Feng Y, Shabashvili D, Guryanova OA. Alterations to DNMT3A in hematologic malignancies. Cancer Res. 2021;81:254–63.

Midic D, Rinke J, Perner F, Müller V, Hinze A, Pester F, et al. Prevalence and dynamics of clonal hematopoiesis caused by leukemia-associated mutations in elderly individuals without hematologic disorders. Leukemia. 2020;34:2198–205.

Zhang X, Su J, Jeong M, Ko M, Huang Y, Park HJ, et al. DNMT3A and TET2 compete and cooperate to repress lineage-specific transcription factors in hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1014–23.

Xue L, Pulikkan JA, Valk PJM, Castilla LH. NrasG12D oncoprotein inhibits apoptosis of preleukemic cells expressing Cbfβ-SMMHC via activation of MEK/ERK axis. Blood. 2014;124:426–36.

Xu Y, Li Y, Xu Q, Chen Y, Lv N, Jing Y, et al. Implications of mutational spectrum in myelodysplastic syndromes based on targeted next-generation sequencing. Oncotarget. 2017;8:82475–90.

Li Q, Haigis KM, McDaniel A, Harding-Theobald E, Kogan SC, Akagi K, et al. Hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis in mice expressing oncogenic NrasG12D from the endogenous locus. Blood. 2011;117:2022–32.

Gough SM, Slape CI, Aplan PD. NUP98 gene fusions and hematopoietic malignancies: common themes and new biologic insights. Blood. 2011;118:6247–57.

Park M-S, Kim B, Jang JH, Jung CW, Kim H-J, Kim H-Y. Rare non-cryptic NUP98 rearrangements associated with myeloid neoplasms and their poor prognostic impact. Ann Lab Med. 2025;45:53–61.

Boultwood J, Perry J, Pellagatti A, Fernandez-Mercado M, Fernandez-Santamaria C, Calasanz MJ, et al. Frequent mutation of the polycomb-associated gene ASXL1 in the myelodysplastic syndromes and in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:1062–5.

Gelsi-Boyer V, Brecqueville M, Devillier R, Murati A, Mozziconacci M-J, Birnbaum D. Mutations in ASXL1 are associated with poor prognosis across the spectrum of malignant myeloid diseases. J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:12.

Inoue D, Kitaura J, Togami K, Nishimura K, Enomoto Y, Uchida T, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes are induced by histone methylation–altering ASXL1 mutations. J Clin Investig. 2013;123:4627–40.

Kaisrlikova M, Vesela J, Kundrat D, Votavova H, Dostalova Merkerova M, Krejcik Z, et al. RUNX1 mutations contribute to the progression of MDS due to disruption of antitumor cellular defense: a study on patients with lower-risk MDS. Leukemia. 2022;36:1898–906.

Illango J, Sreekantan Nair A, Gor R, Wijeratne Fernando R, Malik M, Siddiqui NA, et al. A systematic review of the role of runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1) in the pathogenesis of hematological malignancies in patients with inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Cureus. 2022. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.25372.

Graubert TA, Shen D, Ding L, Okeyo-Owuor T, Lunn CL, Shao J, et al. Recurrent mutations in the U2AF1 splicing factor in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:53–57.

Wu S-J, Tang J-L, Lin C-T, Kuo Y-Y, Li L-Y, Tseng M-H, et al. Clinical implications of U2AF1 mutation in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and its stability during disease progression. Am J Hematol. 2013;88. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.23541.

Fei DL, Zhen T, Durham B, Ferrarone J, Zhang T, Garrett L, et al. Impaired hematopoiesis and leukemia development in mice with a conditional knock-in allele of a mutant splicing factor gene U2af1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1812669115.

Rinke J, Chase A, Cross NCP, Hochhaus A, Ernst T. EZH2 in myeloid malignancies. Cells. 2020;9:1639.

Rinke J, Müller JP, Blaess MF, Chase A, Meggendorfer M, Schäfer V, et al. Molecular characterization of EZH2 mutant patients with myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2017;31:1936–43.

Ling VY, Saw J, Tremblay CS, Sonderegger SE, Toulmin E, Boyle J, et al. Attenuated acceleration to leukemia after Ezh2 loss in Nup98-HoxD13 (NHD13) myelodysplastic syndrome. Hemasphere. 2019;3. https://doi.org/10.1097/HS9.0000000000000277.

Bülbül H, Kaya ÖÖ, Karadağ FK, Olgun A, Demirci Z, Ceylan C. Prognostic impact of next-generation sequencing on myelodysplastic syndrome: a single-center experience. Medicine. 2024;103:e39909.

Inoue D, Abdel-Wahab O. Modeling SF3B1 mutations in cancer: advances, challenges, and opportunities. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:371–3.

Kon A, Yamazaki S, Ota Y, Kataoka K, Shiozawa Y, Morita M, et al. Srsf2 P95H mutation causes impaired stem cell repopulation and hematopoietic differentiation in mice. Blood. 2015;126:1649.

Smeets MF, Tan SY, Xu JJ, Anande G, Unnikrishnan A, Chalk AM, et al. Srsf2 P95H initiates myeloid bias and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative syndrome from hemopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2018;132:608–21.

Xu JJ, Chalk AM, Wall M, Langdon WY, Smeets MF, Walkley CR. Srsf2P95H/+ co-operates with loss of TET2 to promote myeloid bias and initiate a chronic myelomonocytic leukemia-like disease in mice. Leukemia. 2022;36:2883–93.

Kon A, Yamazaki S, Nannya Y, Kataoka K, Ota Y, Nakagawa MM, et al. Physiological Srsf2 P95H expression causes impaired hematopoietic stem cell functions and aberrant RNA splicing in mice. Blood. 2018;131:621–35.

Bao Z, Li B, Qin T, Xu Z, Qu S, Jia Y, et al. Molecular characteristics and clinical implications of TP53 mutations in therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood Cancer J. 2025;15:58.

Bahaj W, Kewan T, Gurnari C, Durmaz A, Ponvilawan B, Pandit I, et al. Novel scheme for defining the clinical implications of TP53 mutations in myeloid neoplasia. J Hematol Oncol. 2023;16:91.

Li Y, Yang S, Yang S. Deficiency of Trp53 and Rb1 in myeloid cell lineage spontaneously develops acute myeloid leukemia in a mouse model. Genes Dis. 2024;11:4–6.

Maegawa S, Gough SM, Watanabe-Okochi N, Lu Y, Zhang N, Castoro RJ, et al. Age-related epigenetic drift in the pathogenesis of MDS and AML. Genome Res. 2014;24:580–91.

Li Z, Cai X, Cai C-L, Wang J, Zhang W, Petersen BE, et al. Deletion of Tet2 in mice leads to dysregulated hematopoietic stem cells and subsequent development of myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2011;118:4509–18.

Garcia-Ruiz C, Martínez-Valiente C, Cordón L, Liquori A, Fernández-González R, Pericuesta E, et al. Concurrent Zrsr2 mutation and Tet2 loss promote myelodysplastic neoplasm in mice. Leukemia. 2022;36:2509–18.

Alawieh D, Cysique-Foinlan L, Willekens C, Renneville A. RAS mutations in myeloid malignancies: revisiting old questions with novel insights and therapeutic perspectives. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14:72.

Yoshimi A, Balasis ME, Vedder A, Feldman K, Ma Y, Zhang H, et al. Robust patient-derived xenografts of MDS/MPN overlap syndromes capture the unique characteristics of CMML and JMML. Blood. 2017;130:397–407.

Braun BS, Tuveson DA, Kong N, Le DT, Kogan SC, Rozmus J, et al. Somatic activation of oncogenic Kras in hematopoietic cells initiates a rapidly fatal myeloproliferative disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:597–602.

Xu H, Deblassio TR, Armstrong SA, Nimer S. Role of p21 in a mouse model of NUP98-HOXD13 fusion driven myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Blood. 2014;124:4616.

Choi CW, Chung YJ, Slape C, Aplan PD. A NUP98-HOXD13 fusion gene impairs differentiation of T and B lymphocytes. Blood. 2007;110:2650.

Greenblatt SM, Li L, Slape C, Novak RL, Duffield AS, Nguyen B, et al. Knock-in of a FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutation cooperates with a NUP98-HOXD13 fusion to generate acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:865.

Chung YJ, Choi CW, Slape C, Fry T, Aplan PD. A NUP98-HOXD13 fusion gene induces a transplantable myelodysplastic syndrome in mice. Blood. 2007;110:401.

Nagase R, Inoue D, Pastore A, Fujino T, Hou H-A, Yamasaki N, et al. Expression of mutant Asxl1 perturbs hematopoiesis and promotes susceptibility to leukemic transformation. J Exp Med. 2018;215:1729–47.

Wang J, Li Z, He Y, Pan F, Chen S, Rhodes S, et al. Loss of Asxl1 leads to myelodysplastic syndrome–like disease in mice. Blood. 2014;123:541–53.

Zhang Y, Yan X, Chen A, Sashida G, Xiao Z, Huang G. Modeling and targeting MLL-PTD/RUNX1 related MDS/AML in mouse. Blood. 2013;122:2746.

Shirai CL, White BS, Tripathi M, Tapia R, Ley JN, Ndonwi M, et al. Mutant U2AF1-expressing cells are sensitive to pharmacological modulation of the spliceosome. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14060.

Karantanos T, Gondek LP, Varadhan R, Moliterno AR, DeZern AE, Jones RJ, et al. Gender-related differences in the outcomes and genomic landscape of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome/myeloproliferative neoplasm overlap syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2021;193:1142–50.

Mochizuki-Kashio M, Aoyama K, Sashida G, Oshima M, Tomioka T, Muto T, et al. Ezh2 loss in hematopoietic stem cells predisposes mice to develop heterogeneous malignancies in an Ezh1-dependent manner. Blood. 2015;126:1172–83.

Musheer Aalam SM, Viringipurampeer IA, Walb MC, Tryggestad EJ, Emperumal CP, Song J, et al. Characterization of transgenic NSG-SGM3 mouse model of precision radiation-induced chronic hyposalivation. Radiat Res. 2022;198. https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-21-00237.1.

Rongvaux A, Willinger T, Martinek J, Strowig T, Gearty SV, Teichmann LL, et al. Development and function of human innate immune cells in a humanized mouse model. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:364–72.

Willis E, Verrelle J, Banerjee E, Assenmacher C-A, Tarrant JC, Skuli N, et al. 22 humanized NOG-EXL mice exhibit improved overall survival and less severe myeloid cell activation relative to humanized NSG-SGM3 mice. In: Regular and young investigator award abstracts. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, London; 2023. pp. A24.

Chen J, Liao S, Xiao Z, Pan Q, Wang X, Shen K, et al. The development and improvement of immunodeficient mice and humanized immune system mouse models. Front Immunol. 2022;13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1007579.

Pearson T, Shultz LD, Miller D, King M, Laning J, Fodor W, et al. Non-obese diabetic–recombination activating gene-1 (NOD– Rag 1 null) interleukin (IL)-2 receptor common gamma chain (IL 2 rγ null) null mice: a radioresistant model for human lymphohaematopoietic engraftment. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;154:270–84.

Minegishi N, Minegishi M, Tsuchiya S, Fujie H, Nagai T, Hayashi N, et al. Erythropoietin-dependent induction of hemoglobin synthesis in a cytokine-dependent cell line M-TAT. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27700–4.

Tohyama K, Tsutani H, Ueda T, Nakamura T, Yoshida Y. Establishment and characterization of a novel myeloid cell line from the bone marrow of a patient with the myelodysplastic syndrome. Br J Haematol. 1994;87:235–42.

Mishima Y, Terui Y, Mishima Y, Katsuyama M, Mori M, Tomizuka H, et al. New human myelodysplastic cell line, TER-3: G-CSF specific downregulation of Ca 2 + /calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV. J Cell Physiol. 2002;191:183–90.

Kida J, Tsujioka T, Suemori S, Okamoto S, Sakakibara K, Takahata T, et al. An MDS-derived cell line and a series of its sublines serve as an in vitro model for the leukemic evolution of MDS. Leukemia. 2018;32:1846–50.

Funding

CT is funded by an international grant of the European Commission—Horizon Europe Framework Network, HORIZON-TMA-MSCA-DN, Proposal Number 101227725—“Advancing in the CHallenge of Improving Lymphoma and LEukemia Survival—ACHILLES”, as well as by a bilateral collaboration grant between Romania and Moldova (PN-IV-P8-8.3-ROMD-2023-0036). HE is funded by a national grant of the Romanian Research Ministry—PNRR 2024-2026 (PNRR/2022/C9/MCID/18, Contract No. 760278/26.03.2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RM and DG review conceptualization, literature search, and manuscript drafting. CSM figure preparation, manuscript structure, and content coordination. RF and SP table preparation and data organization. LB content input and section revision. EA, MM, GG, and RH critical review and scientific recommendations. ADB scientific oversight and manuscript approval. HE project mentorship and scientific oversight. CT project supervision, manuscript editing and final approval. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Edited by Professor Hans-Uwe Simon

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Munteanu, R., Gulei, D., Moldovan, C.S. et al. Humanized mouse models in MDS. Cell Death Dis 16, 531 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-025-07861-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-025-07861-0