Abstract

Addressing mucosal inflammatory disorders in the ocular surface or respiratory system remains a formidable challenge owing to the limited penetration of biological therapeutics across epithelial barriers. In this study, we explored the potential of human single-domain antibodies (UdAbs) as topical therapeutics for the targeted modulation of interleukin-33 (IL-33) in two mucosal-associated inflammatory disorders. The anti-IL-33 UdAb A12 demonstrated potent inhibition of the IL-33-mediated signaling pathway, despite not potently blocking the IL-33 receptor interaction. Compared with the anti-IL-33 control IgG itepekimab, the topical delivery of A12 resulted in significantly elevated corneal concentrations in vivo, which resulted in negligible ocular penetration. Moreover, A12 considerably ameliorated dry eye disease severity by exerting anti-inflammatory effects. Furthermore, in another murine model of allergic asthma, inhaled A12 substantially reduced overall lung inflammation. Our findings revealed the capacity of UdAbs to penetrate mucosal barriers following noninvasive localized delivery, highlighting their potential as an innovative therapeutic strategy for modulating mucosal inflammation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

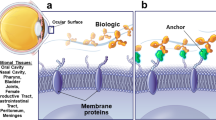

Inflammatory disorders, such as dry eye disease or allergic asthma, significantly impact quality of life and contribute to increased mortality [1]. These disorders are characterized by aberrant inflammatory responses localized to mucosal epithelia, including the ocular surface and pulmonary airways. To date, a number of therapeutic antibodies targeting inflammation-related targets have been widely developed for the treatment of diseases such as neovascular age-related macular degeneration and severe asthma [2, 3]. However, the impermeable nature of mucosal barriers limits the penetration of systemically administered antibodies. For example, less than 2% of intravenously injected antibodies reach ocular tissues because of the outer blood–retinal barrier of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) with tight junctions [4]. Similarly, previous pharmacokinetic studies in primates revealed that only ~0.2% of systemically administered antibodies could be recovered in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid [5]. The poor bioavailability at inflamed mucosal sites leads to suboptimal therapeutic effects and often necessitates high systemic doses, increasing the risk of adverse effects [6]. In recent years, a variety of nonsystemic approaches, such as local injection of therapeutic antibodies to improve local concentrations, have been suggested for ocular diseases [7]. Nonetheless, specialized personnel are needed for administration, which places a tremendous burden on individuals and the health-care system and results in poor patient compliance. Furthermore, the invasive nature of local injection can result in trauma and a high risk of infection. Therefore, there has been significant interest in developing a more tolerable therapeutic strategy for long-term treatment regimens.

Topical delivery is the most common and convenient method for preventing the abovementioned complications and efficiently targeting mucosal inflammatory disorders. However, few studies have reported the use of topical delivery platforms for therapeutic antibodies. First, their large molecular weight and poor tissue penetration decrease their delivery efficiency and affect drug distribution. Additionally, antibodies are susceptible to denaturation and aggregation when formulated for localized delivery or under extra pressure, which may lead not only to loss of activity but also to improved immunogenicity. While topically delivered bevacizumab with cell-penetrating peptides can deliver antibodies to the posterior segment and exert therapeutic effects in a model of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) [8], concerns remain regarding the stability and immunogenicity of such complexes, which may hinder further development. Various kinds of engineered smaller antibody fragments, such as licaminlimab, a single-chain antibody fragment (scFv) that binds to TNF-α, have been developed. Topical ocular administration of licaminlimab relieves ocular discomfort in patients with severe dry eye disease (DED) [9]. However, stability and immunogenicity concerns still exist owing to the susceptibility of fragments to aggregation and denaturation.

Single-domain antibodies (sdAbs), alternative novel antibodies derived from the VH domain of camelid heavy-chain-only immunoglobulins, also known as VHHs or nanobodies, are frequently exploited for disease therapy [10]. Like all sdAbs, sdAbs are small (12–15 kDa), retain strong affinity for binding to antigens, and possess high stability [11]. In combination, this enables them to withstand high temperature and pressure, extreme pH, and proteolysis and maintain functionality, which lends them particularly well to topical delivery. Nevertheless, the animal origin of nanobodies raises safety concerns related to the immunogenicity caused by nonhuman sequences, resulting in their limited applications in the clinic. Our group previously developed a human single-domain antibody (UdAb) library by grafting human naïve complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) into framework regions of a heavy chain variable region allele [12]. We demonstrated that high-affinity UdAbs targeting various targets are highly stable and can be delivered via inhalation [13, 14]. As a proof of concept, one bispecific antibody integrating two UdAbs recognizing different epitopes has completed a phase II clinical trial, indicating good tolerability and safety [CXSL2300258].

Type 2 cytokines are crucial to the pathogenesis of many inflammatory diseases [15]. One of the predominant epithelial cell–derived cytokines, interleukin-33 (IL-33), has emerged as an important initiator of mucosal inflammation. IL-33 belongs to the IL-1 family [16] and is widely expressed in mucosal endothelial cells [17, 18]. When cells are damaged or stressed by allergens or pathogens, IL-33, a key alarm cytokine, is released from the epithelium and other local stromal compartments and activates signaling pathways mediated by the IL-33-ST2 axis, thereby triggering the innate and adaptive immune systems [19]. Recent studies have revealed that the aberrant increase in IL-33 exacerbates mucosal inflammation in diseases such as asthma [20], atopic dermatitis [21], rheumatoid arthritis [22], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [23], and dry eye diseases [24]. Indeed, neutralizing IL-33 with monoclonal antibodies has shown efficacy in dampening mucosal inflammation in animal models [25, 26]. However, in a clinical study of patients with moderate-to-severe asthma treated with itepekimab (REGN3500), a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-33 showed inferior therapeutic efficacy compared with approved therapeutics via subcutaneous administration [27], suggesting the low effectiveness of systemic antibody delivery for the treatment of mucosal inflammation. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the potential of UdAbs as topical therapeutics for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. For this purpose, we developed a UdAb that targets IL-33, named A12, which exhibited superior structural integrity and high-affinity antigen binding (3.04 nM). Although UdAb A12 did not block the interaction of IL-33 with its receptor, ST2, it potently inhibited the IL-33 signaling pathway in vitro. We utilized two models, dry eye disease (DED) and allergic asthma, to investigate the therapeutic efficacy of the topical delivery of A12. In a murine DED model, topical ocular instillation of UdAb A12 demonstrated superior anti-inflammatory efficacy in vivo, as assessed by disease scoring. Furthermore, in an ovalbumin-induced allergic asthma model, inhalation of UdAb A12 markedly reduced IgE levels, lung eosinophilia, and lung inflammation. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of UdAbs as topical biologics for the localized treatment of mucosal inflammatory disorders.

Results

UdAb A12 inhibits the IL-33-induced signaling pathway by targeting a nonblockade epitope for its receptor interaction

The full-length human IL-33 protein is composed of two evolutionarily conserved domains, the N-terminal nuclear domain (amino acids 1–65) for nuclear localization and the C-terminal IL-1-like cytokine domain (amino acids 112–270), which is responsible for the conformation of the IL-33/ST2 complex and confers cytokine-like activities [28]. Therefore, the coding sequences of the C-terminal domain, including amino acids 112–270, were synthesized and cloned and inserted into an expression vector. After expression and purification, the IL-33 protein was biotinylated and used as an antigen for antibody panning from a naïve phage library displaying UdAb (Fig. 1A) [12]. Binding to IL-33 was enriched during four rounds of selection, and eight unique UdAbs were identified. These UdAbs were expressed in Escherichia coli and characterized for their biophysical properties, including expression yield, purity, aggregation and thermal stability. Among these, A12 presented a single peak via size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and dynamic light scattering (DLS), whereas most UdAbs tended to aggregate and form large particles (Supplementary Fig. S1A, B). In the thermal stability experiment, A12 demonstrated comparable thermal stability to the other UdAbs, with no superior thermal stability (Supplementary Fig. S1C). The hydrodynamic diameter (Dh) of A12 was similar to that of VHH and smaller than that of bivalent VHH and IgG (Supplementary Fig. S1D). The results of hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC) also indicated that the A12 antibody is hydrophilic and comparable to the marketed monoclonal antibodies Itepekimab and Trastuzumab (Supplementary Fig. S1E). Moreover, the molecular weight (MW) of A12 was 15165.12 Daltons, which is consistent with the predicted MW (Supplementary Fig. S1F). Size-exclusion chromatography-multiangle light scattering (SEC-MALS) further revealed a primary peak at 7.82 mL, indicating an MW of 17078 Da, with no detectable aggregation observed (Supplementary Fig. S1G). Notably, UdAb A12 exhibited the most advantageous properties among all the tested antibodies and had a binding affinity of 3.04 nM (kon = 4.60 × 10³ M⁻¹s⁻¹, koff = 1.40 × 10⁻⁵s⁻¹), as measured by biolayer interferometry (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, UdAb A12 specifically bound to hIL-33 and did not bind to unrelated antigens (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Identification and characterization of fully human single-domain antibodies (UdAbs) that target IL-33. A Screening strategy for anti-IL-33 fully human single-domain antibodies via a phage display library. In brief, four rounds of UdAb panning were performed on biotinylated IL-33. The enrichment of antigen-specific clones was assessed by soluble ELISA after the fourth round. The positive clones were subsequently sequenced and purified for further verification. B Binding affinity of A12 for IL-33 determined via BLI; the KD value is shown. C Competition of antibodies (A12 and Itepekimab) with ST2 for IL-33 binding and with each other and the inhibition of the IL1RAcP-IL-33-ST2 binary complex by antibodies were determined via BLI. The values are the percentage of binding that occurred during competition in comparison with noncompeted binding, which was normalized to 100%, and the range of competition is indicated by the box color. Residual binding <30% indicates strongly competing pairs, residual binding 30–70% indicates intermediate competition, and residual binding >70% indicates noncompeting pairs. D The inhibition of IL-33-induced NF-κB activity by 10 μg/mL antibodies or ST2-Fc was determined by immunofluorescence staining, with DAPI (blue) for nuclei and NF-κB (green)

IL-33 signals to cells through the membrane-bound receptor ST2 [29]. Thus, we investigated whether A12 blocked the interaction between IL-33 and ST2 via competitive binding assays. We found that the ability of IL-33 to bind to ST2 decreased to 70% in the presence of A12 (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. S3A), indicating that it likely binds to a partially overlapping epitope with ST2. However, the IL-33 neutralizing antibody Itepekimab, a human IgG4 antibody developed by Regeneron, Inc., was in a phase II clinical trial [27] and did not compete with ST2 (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. S3A). Moreover, competitive binding studies revealed that A12 and tepekimab do not share an overlapping epitope on IL-33 (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. S3B), indicating that A12 recognizes a different epitope on IL-33.

Studies have revealed that the binding of ST2 allows IL-33 to interact with IL-1RAcP, an IL-1 superfamily member coreceptor, and this IL-33 receptor complex signals through the MyD88, IRAK1, and IRAK4 kinases and TRAF6 to culminate in the activation of several MAP kinases and NF-κB [16, 30]. Therefore, we next tested whether A12 impacted the formation of the IL-33/ST2/IL-1RAcP ternary signaling complex. Interestingly, A12 inhibited the recruitment of the IL-1RAcP coreceptor to the binary IL-33/ST2 complex, similar to that of tepekimab (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. S3C–E). Moreover, flow cytometry revealed that preincubation of the IL-33/ST2 complex with an antibody (A12 or itepekimab) significantly reduced the binding of the IL-33/ST2 binary complex to Huh-7 cells, which express IL1RAcP on their surface [31] (Supplementary Fig. S3F, G).

To explore the binding epitopes of A12, we performed alanine scanning mutagenesis on the IL-33 protein at the sites involved in receptor and coreceptor binding [32, 33] (Supplementary Fig. S4A). We successfully constructed and expressed a total of 11 single-point mutants and 9 double-point mutants (Supplementary Fig. S4B). As expected, the S162A and Y163A mutations at site 2 of the IL-33/ST2 interface significantly reduced the binding affinity of A12 for ST2 (Supplementary Fig. S4C–E), indicating that A12 primarily interacts with site 2 of the IL-33/ST2 interface. Typically, antibody‒antigen interactions involve a single binding site, whereas IL-33 and ST2 interact at two separate binding sites. This characteristic explains the limited competition with ST2 for binding to IL-33 via A12. Since IL-33 does not directly bind to the coreceptor IL1RAcP [33], mutations in IL-33 that have been reported in previous studies as related to IL1RAcP binding do not substantially affect the binding affinity of A12 (Supplementary Fig. S4C–E). These findings demonstrated that A12 does not directly disrupt coreceptor binding but rather affects the conformation of the IL-33/ST2 binary complex, thereby influencing its interaction with the coreceptor.

To further elucidate the impact of A12 on IL-33 signaling, we utilized a HUVEC line expressing the IL-33 receptor ST2 and the coreceptor IL-1RAcP to assess the effects on the NF-κB pathway. We first confirmed that IL-33 could activate NF-κB signaling by inducing the nuclear translocation of NF-κB (Fig. 1D). Next, prior to preincubation with IL-33 and A12 or control antibody at a concentration of 10 μg/mL, the mixture was added to HUVECs, and NF-κB activation signaling was measured. We observed that A12 markedly suppressed IL-33-induced NF-κB activation (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Fig. S5A), indicating that A12 can potently inhibit IL-33 downstream signaling. Moreover, we used Western blotting (WB) to detect the phosphorylation and activation of NF-κB (p65) induced by IL-33 in HUVECs. The WB results revealed that A12 tended to reduce IL-33-induced NF-κB phosphorylation, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. S5B, C). In summary, although A12 does not directly block IL-33 binding to ST2, it can effectively inhibit IL-33-mediated signal transduction through interference with IL-1RAcP coreceptor recruitment and attenuation of NF-κB activation.

Blockade of IL-33 has anti-inflammatory effects in vitro

Recently, emerging studies have indicated that the IL-33/ST2 axis is also involved in the pathogenesis of a wide range of ocular diseases, such as dry eye disease (DED) [17]. To evaluate the potential efficacy of blocking IL-33 activity via A12, we employed a hyperosmotic stress-induced human ocular epithelial cell (HCEC) model of DED. HCECs represent the frontline of innate ocular immunity [34]. When HCECs were exposed to 500 mOsm of hyperosmolarity stress, we characterized the kinetics of inflammatory cytokine expression in HCECs. Consistent with previous studies [35], we observed that hyperosmotic stress significantly increased the expression of IL-33, as well as the mRNAs of other proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL1-β and TNF-α (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the peak IL-33 mRNA expression occurred at 15 min posthyperosmotic stress insult and returned to normal levels by 24 h. In contrast, the mRNA expression of IL-6 and TNF-α peaked at 30 min, whereas that of IL1-β peaked at 4 h poststress and maintained their increased expression at 24 h (Fig. 2A). The temporal pattern underscores the alarming role of IL-33. Since the IL-33 expression level peaked at 15 min poststress, we first utilized this timepoint to investigate the inhibitory activity of A12. Compared with normal osmotic conditions, hyperosmotic stress dramatically increased the IL-33 concentration in the supernatant and IL-33 mRNA expression in HCECs (Fig. 2B, C). In contrast, A12 treatment led to a dose-dependent reduction in IL-33, with 2 μg/mL A12 decreasing the concentration of IL-33 to 25.95 pg/mL (Fig. 2B). Further assessment revealed that 2 μg/mL A12 significantly downregulated hyperosmotic stress-induced IL-33, IL-6, TNF-α and IL1-β mRNA expression (p < 0.01, p < 0.05, p < 0.001, and p < 0.05, respectively) (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, at 24 h poststress, the IL-33 concentration in the supernatants increased to 96.16 pg/mL, whereas it was 58.97 pg/mL (Fig. 2D). Upon A12 treatment, the mRNA level of IL-33 promptly decreased, simultaneously suppressing the mRNA expression of IL-6, TNF-α and IL1-β (Fig. 2E). Similarly, cell viability assays also revealed a decrease in viability of 56.3% after hyperosmotic stimulation, while A12 at 2 μg/mL significantly improved cell viability (p < 0.0001, Fig. 2F). Compared with tepekimab, an anti-IL-33 monoclonal antibody in an IgG format, A12 demonstrated comparable anti-inflammatory effects and enhanced cell viability at the same concentration (Supplementary Fig. S6). Together, these in vitro results demonstrated the potent anti-inflammatory effects of A12 in DED models, supporting further investigation of its therapeutic potential in vivo.

Anti-inflammatory effect of A12 in vitro. A HCECs were treated with 500 mOsm HS medium to induce DED. The expression of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-33, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, in HCECs at different times after hyperosmotic stress, 0 min, 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 12 h and 24 h, was analyzed via RT‒qPCR. The red rectangle indicates the peak expression of the mRNAs. B Schematic diagram of 500 mOsm hyperosmotic medium (HS) medium-induced DED, where HCECs were treated with a high dose of A12 (2 μg/mL) or a low dose of A12 (0.2 μg/mL). HCECs under physiological osmotic pressure were used as controls (n = 4). After 15 minutes of 500 mOsm HS stimulation, the IL-33 concentration in the supernatants of HCECs was analyzed via ELISA. C mRNA expression levels of inflammatory cytokines in HCECs 15 min after hyperosmotic stress. D Schematic diagram of DED induced with 500 mOsm HS medium for 24 h. E Expression of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-33, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, in HCECs 24 h after hyperosmotic stress. F Cell viability measured by a CCK-8 assay after hyperosmotic stress for 24 h. The results are representative of 2 independent experiments. The error bars represent the means ± SDs. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was employed for multiple comparisons among the different experimental conditions to adjust the calculation power. Statistical significance levels are represented as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 and ns not significant

Topical instillation as an effective route for delivery of A12 to the eye

Topical instillation is the predominant clinical route for drug administration to treat dry eye disease [36]. However, challenges such as large size, poor tissue permeation, and low stability of proteins impede their efficacy via topical instillation [36]. Leveraging the favorable size and stability properties of human single-domain antibodies, we explored the potential of the topical delivery of human single-domain antibodies for corneal penetration.

To compare the performance of A12 with that of conventional IgG antibodies for ocular penetration in mice, we first conjugated the antibodies with DyLight 650 to enable imaging. We employed freshly enucleated eyeballs from wild-type C57BL/6 mice as an ex vivo model. To mimic the disrupted corneal epithelial barrier in dry eye disease, 0.1% benzalkonium chloride was added according to a previous study [37] (Fig. 3A). After 12 h of incubation, imaging revealed greater corneal penetration of A12 than of tepekimab, with a 3-fold greater fluorescence intensity (Fig. 3B, C). To further assess in vivo distribution, C57BL/6 mice were treated with an antibody through topical instillation, and the amount of fluorescence in the eyeballs was measured at various timepoints (Supplementary Fig. S7A). In vivo bioimaging also revealed that A12 was significantly present in the cornea, with the highest fluorescence detectable at 15 min postinstillation (Supplementary Fig. S7B, C). Additionally, A12 was distributed in the conjunctiva (Supplementary Fig. S7D). In contrast, there were few cases of tepekimab in the cornea and none in the conjunctiva. Neither A12 nor itepekimab reached the retina (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Fig. S7E). Therefore, we further quantified the antibody concentrations in eyeballs at various timepoints (Fig. 3D). The results revealed that A12 effectively penetrated ocular tissues, reaching peak concentrations at 1.3 h, whereas tepekimab was not detectable in ocular tissues (Fig. 3E). The amount of A12 penetration was more than 20-fold greater than that of tepekimab (Fig. 3F). Together, these results indicate that A12 has superior permeability across the ocular surface barrier compared with conventional IgG antibodies.

Biodistribution of A12 and Itepekimab in vivo. A Schematic diagram of the antibody penetration experiments. Fluorescence signal (B) and intensity (C) in the cornea and retina of mice after incubation for 12 h in 2 mg/mL A12 or Itepekimab in the presence of 0.1% benzalkonium chloride. The scale bar is 50 μm. D Schematic diagram of A12 biodistribution in mice by instillation. E, F Eyeballs treated by topical instillation of A12 or itepekimab were harvested at different time points for homogenization, after which the concentration of antibodies was determined via ELISA. The results are representative of 2 independent experiments. The error bars represent the means ± SDs. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests were used in the statistical analysis. Statistical significance levels are represented as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 and ns not significant

Potential effects of A12 as a topical eye drop in a DED mouse model

To investigate the anti-inflammatory therapeutic effect of A12, a DED mouse model was induced by subjecting mice to 14 days of low humidity (relative humidity <20%) in a controlled environment (CEC) [38]. We explored whether A12 binds to mouse IL-33 and performed sequence alignments of the IL-33 protein between humans and mice. Numerous differences were observed, and the homology was found to be only 55% [16] (Supplementary Fig. S8A). The results of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) also indicated that A12 specifically binds to human IL-33 (Supplementary Fig. S8B). Therefore, C57BL/6 mice with genetically engineered human IL-33 were used. Following desiccation, the mice were randomly assigned to receive either phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or A12 (60 μg/μL) three times daily for 7 consecutive days, with observations conducted on day 14 (Fig. 4A). Compared with those of the control, positive fluorescein-stained spots were observed on day 0 in DED mice, confirming the successful establishment of the dry eye model (Fig. 4B). In the DED group, a modest decrease in the corneal fluorescein score (CFS) was noted on day 7, followed by a resurgence after the discontinuation of PBS on day 14. Conversely, after 3 days of A12 treatment, corneal fluorescence rapidly decreased, gradually decreased until day 7, and a lower score was maintained even after A12 withdrawal on day 14. Notably, the CFS scores of A12-treated eyes were significantly lower than those of DED-treated eyes at different observation time points (14.25 vs 8.38 on day 3, p < 0.0001; 12.50 vs 5.00 on day 5, p < 0.001; 10.75 vs 3.88 on day 7, p < 0.0001; 10.88 vs 3.75 on day 14, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4B, C). Tear production remained similar between the two groups during the observation period (Supplementary Fig. S9A). Histomorphology assessments were then conducted to investigate structural and morphological changes in the ocular surface after treatment. Hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining revealed thinning of the corneal superficial epithelial layers after DED modeling in the DED group (26.49 μm ± 0.33 μm), whereas the A12 group showed a recovery of corneal epithelial thickness (33.20 μm ± 1.72 μm) similar to that of the control group (33.35 μm ± 2.84 μm) (Fig. 4D, E). The mucus layer, the innermost layer of the tear film responsible for lubrication on the ocular surface and tear film homeostasis, was assessed via periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining. In the DED group, the conjunctival fornix was nearly deprived of goblet cells, whereas A12 treatment markedly restored the goblet cell density to levels comparable to those in the control group (Fig. 4D, F). Consistent with PAS staining, immunofluorescence staining of mucin 5AC (Muc5AC) revealed abundant positive-stained cells in the A12 group (Fig. 4G, Supplementary Fig. S9B). Compared with DED, A12 treatment resulted in a reduction in the mRNA levels of three classic inflammatory cytokines, namely, IL1-β, TNF-α and IL-6, in corneal and conjunctival tissues (Fig. 4H). Furthermore, apoptotic signals were detected in both the cornea and conjunctiva in the DED group. In contrast, A12 treatment rescued cell apoptosis induced by desiccation stress, with few apoptotic cells in ocular surface tissues (Supplementary Fig. S10). These findings indicate the superior therapeutic effect of A12 in restoring corneal structure, maintaining mucin content in the conjunctiva, reducing inflammatory cytokines, and rescuing cell apoptosis.

Instillation of A12 downregulates inflammation in CEC-induced dry eye disease. A Schematic diagram of the therapeutic procedure of A12 in DED. Naïve C57BL/6-IL-33tm1 (hIL-33) mice were used as controls. B, C Representative fluorescein sodium-stained images and corresponding staining scores are shown. (For the control, DED and DED + A12 mouse models, n = 8, 8 and 8, respectively; n number of eyeballs). D Representative H&E staining images of the cornea and conjunctival PAS staining images. The arrows indicate goblet cells. The scale bar is 50 μm. (For the control, DED and DED + A12 mouse models, n = 4, 4 and 4, respectively; n number of eyeballs). E Quantitative analysis of the corneal epithelial thickness in H&E-stained sections (D). F Quantitative analysis of the number of goblet cells per 100 μm in diameter in PAS-stained sections (D). G Immunofluorescence staining of Muc5AC in conjunctiva of mice in DED modeling. The scale bars are 50 μm. H Expression of inflammatory cytokine mRNA levels, including mIl-1β, mTnf-α and mIl-6 detected by RT‒qPCR in cornea and conjunctiva. (For control, DED and DED + A12 mouse models, n = 4, 4 and 4, respectively, n number of eyeballs). I Expression of mST2 and human IL-33 mRNA levels in cornea and conjunctiva. (For control, DED and DED + A12 mouse models, n = 4, 4 and 4, respectively, n: number of eyeballs). J Immunofluorescence staining of hIL-33 and mST2 in conjunctiva in DED modeling. (For control, DED and DED + A12 mouse models, n = 4, 4 and 4, respectively, n number of eyeballs). The scale bars are 50 μm. K Evaluations of F4/80+ cells by immunostaining on the conjunctival. The scale bars are 50 μm. L Representative flow cytometry plots and frequencies of CD11c+MHCII+DCs, CD11c+CD86+ DCs (K), and CD11c+F4/80+ macrophages in the DLNs. (For control, DED and DED + A12 mouse models, n = 4, 4 and 4, respectively, n number of mice). Frequencies of Th1 cells (M) and ST2+ CD4+ cells (N) in the DLNs. Results are representative of 2 independent experiments. Error bars represent means ± SDs. CEC controlled environment chamber. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was employed in the statistical analysis. Statistical significance levels are represented as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 and ns not significant

Encouraged by the promising therapeutic efficacy of the phenotype, we further explored the potential mechanism by which A12 alleviates dry eye syndrome. The gene expression of the A12 target mST2 was upregulated on the ocular surface in the DED group, whereas it was downregulated in the A12 group (Fig. 4I). However, the gene expression of hIL-33 was unchanged in all groups, which may be explained by the function of the alarmin IL-33 (Fig. 4I). Compared with the RT–qPCR results, the immunofluorescence staining results revealed noticeably positive expression of the hIL-33 and mST2 proteins in the conjunctival stroma (Fig. 4J, Supplementary Fig. S11). Ocular surface immunoregulation relies significantly on the integrity of the corneal epithelium and goblet cells [39]. In DED, extrinsic insults and inflammatory cytokines disrupt the ocular surface, abrogating immune tolerance and promoting the adoption of “mature” phenotypes by resident antigen-presenting cells (APCs) [40]. These phenotypes are characterized by increased expression of MHC class II (MHC-II) and the costimulatory molecules B7 (CD80 and CD86) [40,41,42]. In this study, we performed immunofluorescence staining for the mature macrophage marker F4/80 on the ocular surfaces of all the groups. We found increased frequencies of F4/80+ cells within the ocular surface in DED mice treated with PBS compared with those in naïve mice, whereas treatment with A12 decreased the frequency of F4/80+ cells (Fig. 4K). In DED, activated antigen-bearing APCs migrate from the ocular surface to the draining lymph node (DLN), where mature APCs can induce naïve CD4+ T cells to differentiate into different effector T cells [43]. We next investigated whether A12 treatment downregulated APC trafficking to DLNs and the priming of T cells. Flow cytometric analysis of DLNs revealed markedly greater frequencies of mature APCs (CD11c+ MHCII+) and macrophages (CD11c+ F4/80+) in the DED group than in the naïve group, while treatment with A12 significantly decreased these frequencies (Fig. 4L, Supplementary Fig. S12A). Moreover, we confirmed that the population of IFN-γ-expressing CD4+ T cells also notably increased in the DED group, whereas a depletion of Th1 cells was found in the A12 group (Fig. 4M, Supplementary Fig. S12B). Additionally, A12 treatment also reduced the frequency of ST2+ CD4+ T cells in the DLNs of DED model mice, but a surprising increase in these cells was found in the DED group (Fig. 4N, Supplementary Fig. S12B).

Furthermore, we also conducted a comparative experiment on the therapeutic efficacy of A12 and tepekimab in DED (Supplementary Fig. S13A). Comparative analysis revealed that A12 treatment significantly improved corneal epithelial integrity (reduced fluorescein staining), restored epithelial thickness, and increased goblet cell density, whereas itepekimab had limited effects (Supplementary Fig. S13B-G). Notably, A12 exhibited more potent anti-inflammatory cytokine activity (Supplementary Fig. S13H, I). These results collectively highlight the superior efficacy of topical A12 in attenuating DED symptoms, preserving goblet cell function and modulating key inflammatory mediators.

Overall, we demonstrated that the human single-domain antibody A12 could be efficiently delivered to the ocular surface via topical instillation, exert an excellent anti-inflammatory profile in DED and holds great potential for future clinical application.

Potential effects of A12 through inhalation in an asthma mouse model

With evidence indicating the significant impact of A12 in alleviating inflammation through blockade of IL-33 signaling, we explored the potential of this unique domain antibody to ameliorate inflammatory pathology in a distinct disease model. Our focus was asthma, a complex condition influenced by genetic susceptibility and environmental interactions, affecting approximately 334 million people worldwide [44]. Asthma, an allergic disorder characterized by elevated levels of type 2 inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13), increased IgE production, and eosinophil infiltration into lung tissues [21], is strongly correlated with increased IL-33 levels [45].

Inhalation delivery has become an emerging route for the treatment of lung diseases. In our previous work, UdAbs were inhaled into aerosol particles 3–5 μm in size and efficiently deposited in the lungs via intranasal inhalation [13]. Here, we also found that A12 strongly bound to IL-33 before or after inhalation and exhibited unchanged binding activities, indicating the high stability of A12 (Supplementary Fig. S14A, B). Furthermore, aerosolization did not cause apparent aggregation of A12, as determined by DLS and HPLC (Supplementary Fig. S14C, D). Moreover, we used a next-generation impactor (NGI) to determine the aerodynamic characteristics of A12 and IgG Itepekimab after aerosolization via a vibrating mesh nebulizer. As expected, inhaled A12 was mostly deposited in stage 5, indicating that the cutoff diameter of A12 after inhalation was approximately 2.08 μm. Therefore, A12 has the potential for aerosol deposition within the respiratory tract. In contrast, the majority of the IgG itepekimab remains in the device under the same conditions (Supplementary Fig. S15A). To test whether aerosol particle size affects the performance of antibodies in mice, we carried out a single-dose in vivo pharmacokinetic study of A12 and Itepekimab through the inhalation route via a high-pressure microsprayer (Supplementary Fig. S15B). After inhalation, three mice per group were euthanized, and the lungs, trachea and blood were collected at the indicated time points. The concentration of antibodies in each sample was quantified via ELISA. The results revealed that IgG itepekimab was deposited mainly in the trachea because of the large number of particles larger than 5 µm, resulting in a failure to deposit in the lungs (Supplementary Fig. S15C–E) [46]. Notably, the concentration of A12 in the lungs was much greater than that in the trachea or circulating blood, indicating the effective deposition of A12 in the lungs (Supplementary Fig. S15C–G). These results indicate that A12 can be delivered directly to the lungs via inhalation.

Finally, we sought to assess the in vivo therapeutic effects of A12 against allergic asthma. We used an ovalbumin (OVA)-induced mouse asthma model that is characterized by eosinophilic asthma through a TH2-mediated inflammatory response and is widely used to verify the anti-asthmatic activity of drugs [47]. C57BL/6-IL-33tm1(hIL-33) mice were intraperitoneally sensitized with a low dose of OVA on day 0 and day 7 and challenged with a high dose of OVA on days 14–16 after inhalation administration (INH) of either PBS or A12 (Fig. 5A). Delivery of A12, which targets IL-33 in the lungs, robustly inhibited multiple features of OVA-induced asthma. Specifically, mice exposed to OVA presented significantly increased levels of serum IgE, whereas A12 inhalation significantly reduced IgE levels (Fig. 5B). Goblet cell metaplasia, a key pathological manifestation of asthma characterized by increased production of Muc5AC, was investigated to determine whether A12 treatment could ameliorate impaired mucociliary clearance in asthma patients. Strikingly, histopathological analysis confirmed a reduction in mucus-producing cells in A12-treated mice (Fig. 5C, D). In parallel with the histopathological findings, A12 inhibited lung Muc5ac mRNA production in OVA-induced allergic asthma (Fig. 5E). Further analysis of the effect of A12 on cellular infiltration via flow cytometry revealed a decrease in lung eosinophil infiltration and the ratio of lung CD4+/CD8+ T cells after A12 treatment (Fig. 5F, Supplementary Fig. S16). Consistent with the findings concerning cell types, analysis of cytokine mRNAs confirmed the upregulation of multiple signature genes related to type 2 inflammasome (IL-33, ST2, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13) in the lung and airway-draining lymph nodes exposed to OVA, whereas the expression of these cytokines was blocked in the A12-treated group (Fig. 5G, H, Supplementary Fig. S17). Moreover, immunofluorescence staining of the lung revealed reduced positive staining of IL-33+ and ST2+ cells in A12-treated mice compared with OVA-exposed mice (Fig. 5I, J). Taken together, the current data suggested that inhalation of A12 significantly reversed pathological progress in an OVA-induced asthma model.

Inhalation of A12 suppresses OVA-induced experimental asthma. A Schematic diagram of the therapeutic evaluation of A12 by inhalation in OVA-induced asthma in hIL-33 transgenic mice (n = 4). Naïve C57BL/6-IL-33tm1 (hIL-33) mice were used as controls (n = 4). B Serum IgE levels determined by ELISA. C H&E and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining of lung sections (original magnification x15). The arrows indicate goblet cells. The scale bar is 50 μm. D Percentages of PAS-positive areas. E Expression of Muc5ac in lung tissue measured via RT‒qPCR. F Lung immune cell quantification of mice exposed to OVA and treated with PBS or A12 as indicated, as determined via flow cytometry. The numbers on the representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting plots indicate the frequencies of eosinophils and T cells. G, H Lung cytokine mRNA levels measured by RT‒qPCR. Immunofluorescence staining of hIL-33 and mST2 in the lung (I) and the mean fluorescence intensity (J). The results are representative of 2 independent experiments. The error bars represent the means ± SDs. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was employed for multiple comparisons in the statistical analysis. Statistical significance levels are represented as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 and ns not significant, i.p. Intraperitoneal, INH inhalation, i.n. Intranasal

In vivo safety of A12 through topical instillation and inhalation

Given the above prominent therapeutic results, ex vivo biosafety evaluations of A12 were carried out using human corneoscleral rims. A TUNEL assay was used to assess cell apoptosis, and as shown in Supplementary Fig. S18, no significant TUNEL signal was observed in the groups treated with A12 at concentrations of 10 mg/mL, 60 mg/mL, or 100 mg/mL. Further in vivo safety assessments demonstrated that A12 exhibited a favorable safety profile, as indicated by the absence of significant histological abnormalities, including in the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, as well as serum biochemical parameters following topical instillation (Supplementary Fig. S19A‒C). Locally, A12 showed excellent tolerability, with normal corneal morphology, epithelial integrity, and preserved tissue architecture (Supplementary Fig. S19D).

Similarly, A12 was highly safe for inhalation. H&E staining revealed no histopathological abnormalities or lesions in the heart, liver, kidney, spleen, or lung (Supplementary Fig. S20A, B). Serum biochemical evaluations revealed no significant differences between the A12-treated and control groups, with all the parameters remaining within the normal range (Supplementary Fig. S20C). Collectively, these results suggest the exceptional biosafety of A12 for both topical instillation and inhalation.

Discussion

IL-33 is known primarily as an alarmin cytokine that triggers immune responses in mucosal inflammatory diseases, underscoring the pressing need for the development of topically applicable IL-33-specific biologics [17, 30]. Here, a fully human single-domain antibody, A12, was developed, which specifically binds to IL-33 and inhibits the IL-33-mediated NF-κB signaling pathway. Importantly, A12 can serve as a topical delivery agent, either via instillation into ocular tissues or inhalation (INH) into the respiratory tract, and has anti-inflammatory therapeutic efficacy in both the DED model and the asthma model.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) stand out as one of the most significant categories of biologics, demonstrating their effectiveness across a diverse range of diseases, which is attributed to their enhanced specificity, increased druggability, and versatile mechanism of action [48]. Since the approval of the first therapeutic antibody in 1986 [49], more than 100 antibody-based therapeutics have been approved [50]. Advancements in antibody engineering and a deeper comprehension of antibodies have led to the emergence of novel antibody formats, including single-chain variable fragment antibodies (scFvs), sdAbs and antibody‒drug conjugates (ADCs) [51]. Among these, sdAbs, comprising only the variable region of the heavy chain, represent the smallest antibody and can recognize some cryptic epitopes, exhibiting enhanced protective efficacy [12, 13]. Compared with camel-derived single-domain antibodies, our UdAbs incorporate human germline framework regions (FR1, FR2, and FR3) and human heavy-chain complementarity-determining regions (CDR1, CDR2 and CDR3). Furthermore, one bispecific antibody integrating two UdAbs has demonstrated good tolerability and safety in humans. Taken together, A12 is anticipated to exhibit low immunogenicity and good safety.

Despite the challenges posed by tissue barriers, topical administration of antibody-based therapeutics remains the preferred delivery route in clinical settings owing to its advantages, including better patient compliance, higher local drug concentration and a lower risk of systemic side effects than systemic injection. In ocular disease, however, topical antibody delivery faces significant challenges owing to the large molecular weight and tight junctions in the cornea. For example, the topical delivery of the monoclonal IgG1 bevacizumab (150 kDa) is limited in penetrating intact corneas unless it is administered through subconjunctival injection [52]. Recent studies have highlighted OCS-02, a scFv that targets TNF-α (26.7 kDa), which is delivered as an eye drop to alleviate severe DED [50]. In comparison, single-domain antibodies prove advantageous because of their stability and smaller size, facilitating easier traversal through ocular surface barriers. The instillation of A12, as demonstrated, achieves high bioavailability, and penetration experiments with fluorescence imaging also revealed a concentrated presence in the corneal epithelium.

Interestingly, the IL-33/ST2 axis is implicated in various nonallergic mucosal inflammatory diseases, including dry eye disease, rheumatoid arthritis and colitis [53]. The ocular mucosal system shares similarities with the airway, including the cover of mucus, presence of goblet cells and immune cells, and mucosal tolerance mechanisms [54]. Dry eye disease (DED) is a multifactorial disorder of the ocular surface characterized by chronic inflammation due to a disturbance in immune homeostasis [55]. In human corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells, both the RNA and protein levels of IL-33 significantly increase under hyperosmotic conditions [24, 56]. Moreover, tears from patients with DED exhibit a significant elevation in the IL-33 concentration, accompanied by elevated levels of various proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [57]. Studies have revealed that the release of IL-33 from the corneal epithelium under environmental stress is associated with corneal defects and the amplification of inflammatory cascades in DED [58]. In the DED model of ST2-deficient mice, there was a notable improvement in the integrity of the ocular surface barrier, along with improvements in other dry eye-related indicators [59]. These findings demonstrate that IL-33 is a promising therapeutic target in DED. The utilization of an anti-IL-33 neutralizing antibody ameliorated corneal epithelial injury [58], which aligns with our own results. Moreover, our data demonstrate that the administration of A12 alleviates ocular mucosal inflammation by downregulating proinflammatory cytokines and blocking the trafficking of APCs and Th1 cells. Notably, in previous studies, mice with DED were subjected to 14 days of treatment to achieve therapeutic efficacy [60]. In contrast, our study revealed that a short 7-day regimen of A12 is sufficient to suppress ocular inflammation in DED patients, and this effect persists even after the withdrawal of A12.

Additionally, previous studies have established that elevated IL-33 levels contribute to asthma exacerbation and steroid resistance [25, 61]. Several IL-33-targeting biologics, including mAbs against ST2 (RG6149; CNTO7160) and mAbs binding to IL-33 (ANB020; REGN3500), have been developed for asthma therapy. However, low efficacy of systemic administration has been reported in clinical trials [62]. Notably, a previous study demonstrated that a bispecific human single-domain antibody exhibited superior therapeutic efficacy through inhalation compared with intravenous administration for treating lung infection [13]. Therefore, we demonstrated the efficient delivery of the single-domain antibody A12 to lung tissues via inhalation. Our results revealed that inhalation of A12 led to a noticeable reduction in various asthma-related indicators, including decreased serum IgE levels, decreased eosinophil infiltration, and the suppression of Th2-related cytokines. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies [53], suggesting the feasibility of A12 in asthma treatment.

Studies have revealed that there is an IL-33-dependent upregulation of IL-33 and its receptor, ST2, which further propagates the inflammatory response and contributes to severe mucosal inflammation. Gene analysis revealed that IL-33 and ST2 mRNA expression significantly increased in response to extrinsic stimuli in the mucosal environment, as did the number of IL-33-expressing cells, the number of ST2-expressing cells and the level of IL-33 expression [25, 59]. Blockade of IL-33 with Itepekimab completely abrogated this increase. Similarly, A12 could inhibit the recruitment of the IL-1RAcP coreceptor to the IL-33/ST2 binary complex, providing a rationale for the observed downregulation, which could explain the downregulation of IL-33 and mST2 mRNA expression in both in vitro and in vivo experiments. Therefore, blocking IL-33 with A12 might disrupt the amplification of the inflammatory response and decrease the perpetual drive of inflammation in the absence of challenge.

Therapeutic mAbs targeting IL-33 for clinical trials tend to utilize the IgG4-PAA format, where the modified Fc portion contains an S228P mutation in the hinge region to reduce half-antibody formation and F234A/L235A mutations to abrogate Fc effector function [25, 63, 64]. Notably, several studies have demonstrated that the introduction of the LALA mutation results in minimal, but sometimes detectable, Fcγ receptor binding activity [65]. Since A12 possesses only the heavy-chain variable region, it completely eliminates the effector functions of the Fc region. Additionally, recent efforts have suggested that this small-sized single-domain antibody exhibits deep tissue penetration and stability. Conjugation with an Fc region increases the molecular weight, significantly diminishing tissue penetration and rendering effective inhalation unfeasible [13]. Therefore, the half-life of antibody fragments can be extended significantly by fusion with a single-domain antibody targeting human serum albumin (HSA) [66], which is limited by its small size and feasibility for topical administration. Moreover, monomeric Fcs consisting of several mutants on the IgG1 Fc dimerization interface with smaller molecules (27 kDa) and enhanced tissue penetration retain the ability to bind to FcRn in a pH-dependent manner and extend the half-life of FcRn [67,68,69].

In summary, the findings presented herein shed light on the unique properties of UdAb A12, which specifically targets IL-33. Inhibiting the IL-33-induced signaling pathway has superior anti-inflammatory efficacy, highlighting the versatility of A12 delivery routes through inhalation or instillation and indicating its therapeutic potential in treating mucosal inflammation diseases. However, there are limitations to this study. First, since A12 targets human IL-33 and does not bind to mouse IL-33, we used hIL-33 transgenic mice, resulting in a relatively small number of mice per group. Second, we used models of DED and asthma and included additional mucosal inflammation-related disease models to further verify the universal anti-inflammatory activity of the anti-IL33 UdAb.

Materials and methods

Study approval

All the procedures related to animal handling, care, and treatment were performed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Basic Medical Sciences at Fudan University in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Fudan University.

Cell culture

Human corneal epithelial cells (hCECs, donated by Professor Weiyun Shi, Qingdao, China) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, donated by Professor Changyou Zhan, Shanghai, China) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM)/HAM F12 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin, and a 100 U/mL streptomycin mixture (Gibco, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Huh-7 cells (preserved in our laboratory) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin, and a 100 U/mL streptomycin mixture (Gibco, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). All the cells were incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C.

Antibody screening of anti-IL-33 UdAbs from phage libraries

The panning antigen IL-33-biotin (109–270) protein was purchased from Acro (ACROBiosystems, Beijing, China). The fully human single-domain antibody library was constructed essentially as described previously [12]. Panning was also carried out essentially as previously described [12]. A total of 4 rounds of panning were performed on biotinylated IL-33. The enrichment of antigen-specific phages after each round of panning was evaluated through polyclonal phage ELISA, as detailed in the ‘Polyclonal phage, monoclonal phage and soluble ELISAs’ section. Positively expressed antibodies from the enriched rounds were identified through monoclonal phage ELISA, as described in the same section.

Protein expression and purification

a) Antibodies: The sequences of single-domain antibodies that were positive by soluble ELISA were cloned and inserted into the pComb3x vector with an N-terminal OmpA signal peptide (MKKTAIAIAVALAGFATVAQA) and C-terminal hexahistidine and a Flag tag and were expressed in E. coli HB2151. The expression plasmid was transformed into bacteria, and a single colony was selected into SB medium supplemented with 100 μg/μL ampicillin. When the SB medium was cultured to A600 nm ~0.6, 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, Yeasen Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) was added to induce expression. After 16 h of expression at 30 °C, the bacteria were collected, resuspended in buffer A (PBS with 500 mM NaCl) and disrupted by high-pressure homogenization, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant of the single-domain antibody was purified with Ni-NTA (Yeasen Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. First, the supernatant containing the single-domain antibody was incubated with Ni-NTA. After incubation, the resin was washed in buffer C (buffer A with 25 mM imidazole), and the antibody was eluted with buffer B (buffer A with 250 mM imidazole). Finally, the antibody was buffer-exchanged into PBS via a Millipore protein ultrafiltration tube (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The amino acid sequence of UdAb fused with the Fc fragment of human IgG1 was cloned and inserted into the mammalian expression vector pSecTag. The resulting plasmid was transfected into HEK293 cells, which were subsequently cultured at 37 °C for 4 days. The supernatant containing the secreted protein was collected and purified via protein G affinity chromatography via Protein G Resin (GenScript Biotech, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Similarly, the heavy and light chain sequences of Itepekimab were cloned and inserted into the mammalian expression vector pTT, and the plasmids encoding the heavy and light chains were cotransfected into HEK293 cells at a 1:1 ratio and cultured at 37 °C for 4 days. The supernatant containing the secreted protein was harvested and purified with Protein G Resin (GenScript Biotech, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

b) IL-33 and ST2: The DNA sequence of IL-33 (112--270) with an N-terminal 6×His tag was cloned and inserted into the pET28a vector and expressed in E. coli Rosetta. Mutations in IL-33 were introduced via a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). SB medium supplemented with 100 µg/µL kanamycin was grown to an OD600 of approximately 0.6, and 1 mM IPTG was added to induce expression. After 16 h of expression at 16 °C, the cells were collected, resuspended in PBS and disrupted by high-pressure homogenization. The purification steps were the same as those described above. The recombinant ST2-Fc and ST2-His amino acids used for binding to IL-33 were expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 Freestyle cells (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The amino acids of ST2 fused with the Fc fragment of human IgG1 or the C-terminal hexahistidine were subsequently cloned and inserted into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.4. The plasmid was transfected into HEK293 cells, which were subsequently incubated at 37 °C for 4 days. The supernatant containing the secreted protein was collected and purified via protein G affinity chromatography via protein G resin (GenScript Biotech, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) or Ni-NTA (Yeasen Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Polyclonal phage, monoclonal phage and soluble ELISA

Costar half-area high binding assay plates (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) were coated with purified antigen protein at a concentration of 100 ng/well in PBS overnight at 4 °C. The plates were then blocked with PBS buffer containing 3% milk (w/v) at 37 °C. For polyclonal phage ELISA, phages from each round of panning were incubated with the immobilized antigen, and bound phages were detected with an anti-M13-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) polyclonal antibody (Pharmacia, New York, NY, USA). For the monoclonal phage ELISA, monoclonal phages from the enriched rounds were incubated with immobilized antigen, and bound monoclonal phages were detected with an anti-M13-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) polyclonal antibody (Pharmacia, New York, NY, USA). For the purified single-domain antibody binding assay, serially diluted antibody solutions were added and incubated for 1.5 h at 37 °C, and bound antibodies were detected with a monoclonal anti-Flag-HRP antibody (Sigma‒Aldrich, Louis, MO, USA; clone number M2). The enzyme activity was measured with the subsequent addition of the substrate ABTS (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), and the signal reading was recorded at 405 nm via a microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA).

Biolayer interferometry (BLI) binding assays

BLI was carried out on an Octet RED96 device (ForteBio, Dallas, TX, USA), and assays were carried out in 96-well black plates. To determine the kinetics of the binding of A12 with IL-33, the hIL-33-Biotin-His protein at 10 μg/mL buffered in 0.04% PBST was immobilized onto SA biosensors (ForteBio, Dallas, TX, USA) and incubated with three serial dilutions of A12 in kinetics buffer (PBS supplemented with 0.04% Tween 20). The experiments included the following steps at 37 °C: (1) baseline in water (60 s); (2) immobilization of hIL-33-Biotin-His protein onto sensors (300 s); (3) baseline in kinetics buffer (60 s); (4) association of A12 for measurement of kon (300 s); and (5) dissociation of A12 for measurement of koff (300 s).

For the unrelated antigens binding to A12, the recombinant A12-Fc protein at 15 μg/mL buffered in 0.02% PBST was immobilized onto AHC biosensors (ForteBio, Dallas, TX, USA) and incubated with one concentration (500 nM) of hIL-33 or unrelated antigens in kinetics buffer (PBS supplemented with 0.02% Tween 20).

All the curves were fitted by a 1:1 binding model via Data Analysis software (ForteBio, Dallas, TX, USA). The mean kon, koff, and KD values were determined by averaging the binding curves within a dilution series with R2 values greater than the 95% confidence level.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

For analysis of the aggregation tendency of UdAbs, the UdAb protein samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 min to remove precipitates. The supernatants were filtered through a 0.45-μm filter and diluted to 1 mg/mL. Measurements were performed on a Zetasizer Nano ZS ZEN3600 (Malvern Instruments Limited, Westborough, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each sample was measured three times.

Size-exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography (SEC-HPLC)

Fifty micrograms of protein were applied to a TSK-Gel Super G3000SW (Tosoh Bioscience, Griesheim, Hesse, Germany) using a Waters AQUITY UPLC H-class system. For the analysis of UdAb properties (Supplementary Fig. S1B), an AdvanceBio SEC 300 A column (2.7 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm) and a 2.7 μm, 4.6 × 50 mm guard column were used. For A12, both before and after aerosolization (Supplementary Fig. S14D), the same AdvanceBio SEC 300 A column (2.7 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm) was used. The mobile phase consisted of PBS buffer (pH 7.4), and the system was run at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The absorbance was monitored at 280 nm. The UV traces were analyzed and integrated by the area under the curve (AUC) to determine the percentages of aggregation, monomers and degradants.

Hydrophobicity determination of UdAbs by HIC-HPLC

The hydrophobicity of the UdAbs was analyzed via HIC-HPLC. HIC-HPLC was carried out using a butylnonporous resin (NPR) column (4.6 mm inner diameter [I.D.] × 10 cm, Tosoh Corporation, Chuo-ku, Tokyo, Japan) with running buffer 20 mM phosphate buffer, 1.5 M (NH4)2SO4, pH 7.0 (mobile phase A), and 20 mM phosphate buffer, 25% isopropanol, pH 7.0 (mobile phase B). A total of 50 μg of UdAbs or IgG (ittepekimab and trastuzumab) was loaded and eluted at a flow rate of 10 mL/min with a gradient of 100% A to 100% B over 2 min. Absorbance at 280 nm was used to detect the elution.

Determination of melting (Tm), onset (Tonset) and aggregation (Tagg) temperatures

The thermal stability of UdAbs was assessed by using an Uncle/UNit system (Unchained Labs, Pleasanton, CA). Briefly, static light scattering (SLS) at 473 nm was used as an indicator of colloidal stability, indicating the onset of aggregation temperature (Tagg), which can be defined as the temperature at which the measured scatter reaches a threshold that is approximately 10% of its maximum value. The changes in the SLS signal represented changes in the average molecular mass observed due to protein aggregation. Thermal stability was evaluated at an intrinsic fluorescence intensity ratio (350/330 nm) by measuring the temperature of the onset of melting. The UdAbs at a concentration of 5 mg/mL were heated from 20 °C to 95 °C in 1 °C increments, with an equilibration time of 60 s before each measurement. Measurements were made in duplicate.

Molecular weight determination of A12 via the SCIEX ZenoTOF 7600 System

The molecular weight of A12 was determined with a SCIEX ZenoTOF 7600 system (SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA). Briefly, A12 was dissolved in 0.1% formic acid solution to ensure proper ionization during mass spectrometry. The prepared sample was injected into a liquid chromatography (LC) system, where gradient elution was initiated to separate the analytes on the basis of their chemical properties. The separated analytes then entered the electrospray ionization (ESI) source for ionization. Full-scan spectra were recorded to detect the m/z signals of the protein. The data were deconvoluted via SCIEX OS software to calculate the molecular weight of A12.

Size-exclusion chromatography-multiangle light scattering (SEC–MALS)

SEC-MALS was conducted on an Agilent Infinity III (Agilent, DE, USA), followed by a MALS detector (DAWN, Wyatt Technology, CA, USA). Separation was performed with an AdvanceBio SEC 130 A (2.7 µm, 7.8 × 300 mm) column. An optimized flow rate of 0.8 mL/min was employed, and the column temperature was set at 35 °C. The data were collected and processed via ASTRA® software V7.2 (Wyatt Technology, CA, USA). The aqueous mobile phase consisted of 25 mM NaH2PO4, 25 mM Na2HPO4, and 300 mM NaCl at pH 7.4 dissolved in HPLC-grade water and was filtered through 0.22 µm membrane filters. Prior to injection, the samples were centrifuged and injected in duplicate (100 µL each).

Binding competition assays

The epitopes of the antibodies against IL-33 were analyzed via BLI. IL-33 (200 nM, blue) was preincubated with A12 (500 nM, red) or Itepekimab (500 nM, green). Sensor tips loaded with ST2 (15 μg/mL) were immersed in wells containing IL-33 or a mixture of IL-33 and antibodies. Competition of tepekimab with A12 for IL-33 binding was also measured by BLI. The immobilized IL-33 was incubated with itepekimab (200 nM, red) or PBST (blue), followed by incubation of the sensors with a mixture of A12 (500 nM, red) with itepekimab (200 nM, red) or A12 (500 nM, blue). On the basis of previous experimental methods [12], we categorized the antibodies into competitive, intermediate competitive and noncompetitive. The antibodies were defined as competing if the presence of the first antibody reduced the signal of the second antibody to less than 30% of its maximal binding capacity and noncompeting when binding was greater than 70%. A level of 30–70% was considered intermediate competition.

Inhibition of IL1RAcP binding to the IL-33-ST2 binary complex

The ability of IL1RAcP to inhibit the IL-33-ST2 binary complex with antibodies was determined by BLI and flow cytometry.

BLI: Sensor tips were loaded with IL-33 (15 μg/mL) and immersed in wells containing either ST2 (200 nM), a mixture of ST2 (200 nM) with A12 (300 nM), or a mixture of ST2 (200 nM) with itepekimab (200 nM). The interaction was allowed to reach binding saturation after 300 s. Subsequently, biosensors were dipped into wells containing the same concentration of IL1RAcP (200 nM).

Flow cytometry

IL-33-biotin (1 μM) was preincubated with ST2 (1 μM) or a mixture of ST2 (1 μM) with antibodies (A12, itepekimab, or negative control, 2 μM) overnight at 4 °C in FPBS (containing 2% fetal bovine serum). A total of 1 × 10⁶ Huh-7 cells were incubated with the above protein mixture for 1 h on ice, followed by two washes with FPBS. The cells were then incubated with APC-conjugated streptavidin (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) for 30 minutes on ice and washed three times with FPBS. Staining was analyzed via flow cytometry (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the data were analyzed via FlowJo 10.4.

NF-κB activation assays

HUVECs were stimulated with a constant concentration of IL-33 with or without proteins (A12, ST2 or Itepekimab) for 30 min. Following stimulation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and blocked before being stained with rabbit anti-NF-kB antibody (ABclonal, Wuhan, Hubei, China; clone number ARC51086). After washing, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). After washing, the nuclei were stained with DAPI. Confocal images were captured via a Leica confocal microscope and processed with LAS AF Lite software. The colocalization of NF-κB with nuclei was quantified via ImageJ software.

Western blotting

Protein was extracted from HUVECs via radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Solarbio, Beijing, China). The samples were sonicated on ice for 30 min to ensure complete lysis of the cellular components. The lysates were then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C, and the supernatants were collected for further analysis. The protein concentration was determined via a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). For SDS‒PAGE analysis, 20 μg of protein from each sample was loaded onto a 4–20% gradient gel and electrophoresed at a constant voltage (80 V for 20 min, followed by 120 V for 45 min) to separate proteins by molecular weight. The proteins were then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk in TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at 25 °C, followed by three washes with TBST. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4 °C with the appropriate primary antibody. After the samples were washed, they were incubated with an HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were washed and developed using a chemiluminescent substrate. Protein signals were visualized with a Kodak imaging system (Wazobia, TX, USA) and quantified via ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Administration of A12 to a hyperosmotic model of HCECs

Hyperosmotic medium (HS) at 500 mOsm was applied to generate inflammatory stress in HCECs. HCECs were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 per well or in 6-well plates at a density of 1.5 × 105 per well. After HCECs reached 50% confluence, the cells in the 96-well plates were treated with HS or HS with a high dose of A12 (2 μg/mL) or itepekimab (2 μg/mL) or a low dose of A12 (0.2 μg/mL). After 15 min or 24 h, the supernatants were collected for ELISA, and after 24 h, the cell viability was measured with a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Dojindo Laboratories, Kamimashiki-gun, Kumamoto, Japan). The cells in the 6-well plates were treated with HS, HS with a high dose of A12 (2 μg/mL) or a low dose of A12 (0.2 μg/mL) and harvested at 0 (before stimulation), 15 min and 24 h for real-time PCR and at each point in the supernatants of hCECs for detection of the IL-33 protein by ELISA, as described in the ‘Determination of the IL-33 levels in the supernatants by ELISA’.

Determination of IL-33 levels in supernatants by ELISA

The supernatants of HCECs were analyzed with commercially available ELISA kits (Multi Science, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions to determine the concentration of IL-33. In brief, each 100 μL sample was added to the wells of a microplate precoated with 50 μL of antibody and then incubated for 2 h at room temperature on a plate shaker set to 100 rpm. The plates were subsequently washed 6 times with phosphate-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (PBST). Subsequently, 100 μL of streptavidin-HRP solution was added to each well, and the samples were incubated for 45 min on a plate shaker set to 100 rpm. Following incubation, the wells were washed six times with PBST. Subsequently, 100 μL of TMB solution was added to each well and incubated for 10 min in the dark before 100 μL of stop solution was added. The microplate was read with a microplate reader (Spark, Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland), and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm, with a reference at 570 nm.

Single-domain antibody penetration experiments

Penetration experiments were carried out as described previously with minor modifications [37]. The fully human single-domain antibodies A12 and Itepekimab used in this experiment were labeled with a DyLight 650 antibody labeling kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). After anesthesia, the eyes of wild-type C57BL/6 mice (SiPeiFu, Beijing, China) were enucleated and rinsed in PBS twice before being incubated in each well. Each eye was incubated with a solution containing 2 mg/mL antibody and 0.1% benzalkonium chloride in a well of a ninety-six-well plate. After 12 h, the eyeballs were carefully removed from the well and rinsed in PBS twice for fluorescence imaging. Eyeballs were fixed in 4% PFA for 24 h and embedded in optimum cutting temperature (OCT) solution (SAKURA, Torrance, CA, USA). The 10-μm frozen slices were freshly sectioned and then observed under a confocal fluorescence microscope at 650 nm.

Biodistribution of antibodies administered by topical instillation

A fully human single-domain antibody A12 or Itepekimab labeled with the DyLight 650 antibody Labeling Kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) at a concentration of 3 mg/mL was administered by instilling 5 μL onto the eyes of wild-type C57BL/6 mice (SiPeiFu, Beijing, China). The mice were sacrificed at distinct time points (0, 5, 10, 15, 30, and 60 min) precisely after administration, soon after which their eyeballs were carefully removed from the orbits and rinsed in PBS twice for fluorescence imaging. Eyeballs were fixed in 4% PFA for 24 h and embedded in optimum cutting temperature (OCT) solution (SAKURA, Torrance, CA, USA). The 10-μm frozen slices were freshly sectioned and then observed under a confocal fluorescence microscope at 650 nm.

The pharmacokinetics of antibodies in mice subjected to topical instillation

The single-domain antibodies A12 and IgG Itepekimab were administered by topical instillation at a concentration of 15 mg/mL. After antibody administration, two mice were sacrificed, and the eyes were collected at the indicated time points. The eyes were weighed, homogenized and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm. The supernatant was harvested and stored at −80 °C for subsequent quantification.

The antibody concentration in the eyes was determined via ELISA. In brief, IL-33 or anti-hFc antibody (100 ng per well) was used to coat a 96-well half-area microplate (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) overnight at 4 °C. The antigen-coated plate was blocked with PBS containing 5% BSA for 1 h at 37 °C and washed three times with PBST (PBS with 0.05% Tween 20). Fifty microlitres of eye homogenate in PBS at a dilution of 1:2 was added for binding at 37 °C for 1.5 h. The plate was washed three times with PBST and incubated with anti-Flag-HRP (Sigma‒Aldrich, Louis, MO, USA; clone number M2) or anti-Fab-HRP (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) for 45 min at 37 °C. The plate was washed five times with PBST, and the enzyme activity was measured by recording the absorbance at 405 nm after a 10-min incubation with ABTS substrate (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Gradient serially diluted purified antibodies were used to generate a quantitative standard curve, which was fitted by a four-parameter logistic model. The antibody concentration in the eye was calculated from the standard curve.

Dry eye model mice

As human and mouse IL-33 exhibit 55% identity at the amino acid level [16] and considering the specificity of A12 binding to human IL-33, human IL-33 transgenic mice were selected according to a previous study [25]. Ten hIL-33 transgenic mice (C57BL/6-IL-33tm1(hIL-33), female, 8 weeks, 20 ± 2 g) were purchased from BIOCYTOGEN (BIOCYTOGEN, Beijing, China). Four mice (8 eyes) housed in a standard environment (temperature: 25 °C; relative humidity: 60%) were used as controls (n = 4, 8 eyes). A controlled environment chamber (CEC) was used to induce experimental DED in mice as described previously [70]. Briefly, the CEC allows continuous regulation and maintenance of the temperature (21–23 °C), relative humidity (<20%), and airflow (15 L/min). The mice were exposed to the CEC for 2 weeks. Then, eight mice were randomly divided into a dry eye group and an A12 treatment group (n = 4, 8 eyes) and received topical instillations of 5 μL of PBS or A12 (300 μg) three times a day for 7 days, after which they were observed for another 7 days in a standard environment (temperature: 25 °C; relative humidity: 60%). On day 28, the eyeball and cervical draining lymph nodes (DLNs) were collected. To compare the therapeutic efficacy of A12 and itepekimab for clinical translation, dosing concentrations were selected on the basis of prior research [27]. A single subcutaneous injection of itepekimab (5 mg/kg) was administered on day 0, while A12 (300 μg) was delivered via topical ocular administration three times daily for 7 days. After seven days of treatment, the samples were observed for another 7 days in a standard environment (temperature: 25 °C; relative humidity: 60%). On day 14, the eyeballs were collected for further evaluation.

Detection of basal tear secretion (Schirmer I test)

The Schirmer I test was performed via the use of phenol red-impregnated cotton threads (Jing Ming Tech Co., Ltd., Tianjing, China) at 5 p.m. on days 0, 3, 5, 7 and 14 (one week after treatment, 2 weeks after modeling). After general anesthesia, the cotton thread was placed onto the lower eyelid conjunctiva near the canthus for 30 s. The length of the reddened part of the cotton thread was measured.

Corneal fluorescein sodium staining score

A total of 5 μL of 1% sodium fluorescein (w/v) was instilled into the lateral conjunctival sac to evaluate the degree of corneal epithelium defects in the mice. The corneal epithelium was visualized with a cobalt blue filter under a slit lamp microscope. Each cornea was divided into 4 quadrants and scored separately by a masked observer via a four-point scale (0–4): 0 points, no staining; 1 point, <30% stained dots; 2 points, >30% nondiffuse stained dots; 3 points, severe diffuse staining but without plaque staining; and 4 points, positive fluorescein plaque. The final score was obtained by adding scores from each quadrant (0–16).

Safety evaluation

Cadaveric human corneoscleral rims were obtained from fresh cadavers and provided by the Eye Bank of the Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat Hospital, Fudan University, under the approval of the hospital ethics committee. The tissues used for the experiments did not meet the criteria for clinical use.

The corneoscleral rim was sectioned into small 2 mm × 1 mm pieces and randomly divided into five groups, which were subsequently placed in Optisol, 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), or A12 at concentrations of 10 mg/mL, 60 mg/mL and 100 mg/mL, respectively, and incubated at 4 °C. The 10% DMSO group was used as a positive control. After 24 h, the tissues were collected for further analysis via the TUNEL assay.

Immunofluorescence and TUNEL assays

After anesthesia, eyeball or lung tissues collected from the mice, as well as human corneoscleral pieces, were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight and processed into 10 μm paraffin sections. For the paraffin sections processed for the immunofluorescence and TUNEL assays, the sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and subjected to antigen retrieval. The slides were then dried at room temperature for 20 min and washed 3 times with PBS. The slides were subsequently incubated in 0.1% Triton X-100 (prepared in PBS) for 15 min. To prepare slides for the TUNEL assay, a commercial kit (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) was used following the manufacturer’s instructions.

For immunofluorescence staining, the slides were blocked in blocking buffer containing 3% BSA in a humidified box at room temperature for 30 min. The slides were incubated with primary antibodies against human IL-33 (1:100, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or ST2 (1:200, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA; clone number 7A2A7) at 4 °C overnight. The slides were then incubated with either an anti-goat secondary antibody (1:500, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA; clone number AB_2925786) or an anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:500, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA; clone number AB_2536180) for 1 h at room temperature. For macrophage detection, the specific antibody F4/80 (1:100, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA; clone BM8) was applied, and the slides were incubated for 1 h. Finally, the nuclei were stained with DAPI. TUNEL images were taken at 10x, and immunofluorescence images were taken at 40× with an oil-immersion microscope (Leica, Witzler, Hesse, Germany).

Aerodynamic particle size measured by a next-generation impactor

To determine the size distribution of the aerosolized antibodies, we used a next-generation impactor (NGI; Beijing Huironghe Technology, Beijing, China) to analyze the aerodynamic parameters of the antibodies according to the USP monograph. There are seven-stage droplet collectors with different cutoff diameters for the collected particles, which are located at the bottom frame. A12 and IgG Itepekimab (4 mg/mL) were aerosolized and deposited on different collection cups under ambient room conditions within 180 s. Specifically, after the assembly was set up and airtightened, a vacuum pump running at a constant flow rate of 15 L/min was used, and the antibody mixture was added and immediately aerosolized into the cascade impactor. Droplets from each collection plate were washed and collected with 0.02% PBST, and then the components were dried before proceeding with the next experiment. The concentration of antibodies in the collected solution was quantified by ELISA, as described in the section ‘The pharmacokinetics of antibodies in mice administered by topical instillation’.

Pharmacokinetics of antibodies in mice administered via inhalation

UdAb A12 and IgG Itepekimab were administered via the intratracheal route via a microsprayer aerosolizer (YUYANBIO, Shanghai, China) at a dose of 10 mg/kg. Following antibody administration, three mice were sacrificed, and lung, trachea and blood samples were collected at the indicated time points (0.5 h, 2 h, 4 h, 8 h and 12 h). The lungs and tracheas were weighed, homogenized and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm to collect the supernatant. The antibody concentration in the supernatant was subsequently determined via ELISA, as described in the ‘The pharmacokinetics of antibodies in mice administered by topical instillation’ section.

Asthma model mice