Abstract

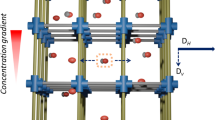

Gradient porous structures enable the fast capillary-directed mass transport and enhance the chemical reaction rate with optimal efficiency and minimal energy consumption. Rational design and facile synthesis of functional mesoporous materials with sheet structure and gradient mesopores still face challenges of stacked structures and unadjustable pore sizes. Herein, an interfacial co-assembly strategy for gradient mesoporous hollow silica sheets is reported. The modulated oil-water interface allows the assembly of gradient mesoporous silica layers on the water-removable ammonium sulfate crystals. The obtained mesoporous silica layers possess narrow pore size distributions (~2.2 nm and ~6.6 nm). Owing to the good mono-dispersity, sheet structure and proper pore size, the designed gradient mesoporous hollow silica sheets can serve as flexible building blocks for fabricating nanoscale molecule filtration device. Experiments reveal that the obtained nanofiltration device shows remarkable gradient rejection rates (range from 23.5 to 99.9%) for molecules with different sizes (range from 1.2 to 4.4 nm).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past decades, functional mesoporous materials with rich structures hold great potential in the fields of energy storage, catalysis technology, biomedicine, adsorption and separation owing to their characteristic properties such as high surface areas, controllable pore structures and pore sizes, large pore volumes, tunable morphologies and dimensions1,2,3,4. Rational design and controllable synthesis of functional mesoporous materials with well-defined proper pore size and structure for the target application scenarios have been a long-pursued goal5,6,7.

Molecule-level filtration has shown great potential in water purification, gas separation and pharmaceutical industries8,9,10. The filtration is performed by applying porous materials to selectively reject or pass molecules with different sizes. Mesoporous sheet structure with proper pore size is highly preferred because of the highest surface utilization efficiency, minimized molecular diffusion within the porous structure, and the precise control of species size during filtration, which is of great challenge to achieve for zero-dimensional, one-dimensional and bulk materials and the commercial filtration materials11,12,13. The commonly used strategies for preparing mesoporous sheet materials with narrow pore size distribution, such as chemical vapor deposition and electrochemical deposition, mainly rely on complicated synthetic procedures or complex equipment. And the obtained materials are usually coexistent with the original substrates or scaffolds, which results in the lack of flexibility. Moreover, the supported non-porous substrate prevents the use of mesoporous sheet materials for substance filtration14,15,16,17,18. Therefore, it is highly desirable to design facile and practical synthesis strategy for fabricating flexible filtration modules with appropriate pore size and sheet filtration structure, to achieve satisfactory size-selective filtration performance.

Herein, an interfacial co-assembly strategy for synthesizing gradient mesoporous hollow silica sheets is reported. In the synthesis process, (NH4)2SO4 crystals grow at the n-pentanol-water interface, and then negatively charged silica oligomers can be confined on the (NH4)2SO4 crystal surface by the Coulomb interaction of NH4+ and co-assembled with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) at the interface to form the first layer of mesoporous silica. By modulating the n-pentanol-water interface to n-hexane-water interface, a second layer of mesoporous silica with a uniform pore size of ~6.6 nm was coated19,20. After removing (NH4)2SO4 core and CTAB template, gradient mesoporous hollow silica sheets were obtained. When applied to nanoscale molecule filtration, the rejection rate increases gradually (from 23.5 to 99.9%) with the increasing of molecular size (from 1.2 to 4.4 nm). The narrow pore size distribution and hollow sheet structure make it capable of precise particle size selection and secondary filtration12,21,22.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and materials

Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, ≧99%), Fe2(SO4)3·xH2O, n-pentanol (AR, 98%), n-hexane (AR, 98%), tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, AR, 98%), Direct red 23 (DR23, 3.3 nm), Reactive red 120 (RR, 2.1 nm), Rhodamine B (RhB, 1.2 nm), Evans blue (EB, 3.1 nm), Rose bengal (RB, 1.5 nm), Congo red (CR, 2.5 nm), Direct red 80 (DR80, 4.4 nm), and Methylene blue (MB, 1.3 nm) were obtained from Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ammonium hydroxide (27 wt%, aqueous solution) was obtained from Beijing Chemical Co. Inc. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, molecular weight 40 kg mol−1) and anhydrous ethanol (EtOH, AR) were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. (Shanghai, China). Hydrochloric acid (37%) was obtained from Shanghai Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. All of the chemicals were used as received in the experiment process without further purification. Deionized water (>18 mΩ) was used for the synthesis.

Characterization

The morphologies and structures of the materials were analyzed with field emission transmission electron microscope (TEM, FEI Tecnai G2 F20S-Twin D573) at 200 kV and field-emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, HITACHI SU8020 and JEOL JSM-6700F) with accelerating voltage of 5 and 15 kV, respectively. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were recorded with a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer using monochromatic Cu Kα irradiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) at 50 kV and 200 mA. The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms were obtained at 77 K on a NOVA 4200e. The decomposition process of samples was measured through thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA Q50) under air flow (10 °C/min) from 40 to 800 °C. The fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) was performed on a Bruker IFS 66 V/S FTIR spectrometer (500-4000 cm−1, KBr pellets). The dye concentrations in the solutions before and after filtration were measured by UV–vis spectra (Shimadzu UV-2450 spectrometer). The optical photos in this paper were taken with a smartphone (K30, Redmi, China). The water contact angle (CA) were measured on a drop shape analysis system at room temperature (Krüss, Germany).

Experimental procedures

In a typical synthesis, PVP (1000 mg) was dispersed in n-pentanol (10 mL) under sonication and stirring. Fe2(SO4)3 aqueous solution (280 μL, 40 mg mL−1), anhydrous ethanol (1000 μL) and CTAB (72 mg) were added subsequently. The mixture was shaken vigorously for 3 min. Then, NH3·H2O (120 μL, 27 wt%) and TEOS (100 μL, 98%) were added and continually stirred for 5 min. The reaction was completed at 30 °C for 3 h without stirring. The fabricated samples (10 mg) were re-dispersed in a mixed solution containing H2O (8 mL), CTAB (50 mg) and NH3·H2O (80 μL). Then, n-hexane (2 mL) was added to the mixed solution. After stirring for 2 h at 500 rpm, TEOS (80 μL) was added dropwise into the mixed solution under mild stirring. This reaction was then completed at room temperature (30 °C) with continuous stirring at 170 rpm for 12 h. The final product was collected and washed with water and ethanol and dried at an oven (65 °C, 8 h). Then, 200 mg of product was treated three times with 20 mL of the extraction solutions (2 mL conc. HCl and 18 mL EtOH) by stirring at 60 °C for 12 h to remove CTAB template and gradient mesoporous hollow silica sheet was finally obtained.

Nanoscale filtration

The nanofiltration device was fabricated by depositing the gradient mesoporous hollow silica sheet dispersion on the surface of commonly used cellulose membrane filters. Typically, the obtained sample (1 mg) was dissolved in anhydrous ethanol (10 mL) under vigorously stirring and ultrasonic treatment. After vacuum filtration, the dispersion was cast over the cellulose membrane filters (Diameter: 13 mm, Pore size: 0.22 μm). After drying at the oven (65 °C, 8 h), the nanofiltration device was obtained. Next, five milliliters of dye solution (20 ppm) was injected into the nanofiltration device and original cellulose membrane filter, respectively. The filtrates were collected and the concentration of dye solutions before and after the filtration were measured by UV–vis absorption spectroscopy. After filtration, the dye molecules on mesoporous silica surfaces and porous channels can be removed by calcination at 600 °C in air. The regenerated mesoporous silica sheets were used for next filtration cycle.

Results and discussion

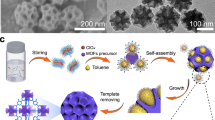

Scheme 1 shows the interfacial co-assembly synthesis process of gradient mesoporous hollow silica sheets. The synthetic process mainly contains three stages:

(a) Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, MW = 40,000) and ethanol were dissolved in n-pentanol firstly. An aqueous solution of iron (III) sulfate (Fe2(SO4)3) and ammonium hydroxide was then introduced into the mixture to form n-pentanol-water interface. The amphiphilic polymer PVP was located on the interface to minimize the interfacial tension and stabilize the oil-water interface. Driven by the electrostatic attraction and hydrogen bonding, the SO42− and NH4+ were aggregated by protonated PVP and formed (NH4)2SO4 crystals. (b) The subsequently introduced tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) was hydrolyzed into silica oligomers, and these negatively charged oligomers can be confined on the (NH4)2SO4 crystal surface by the Coulomb interaction of NH4+ and co-assembled with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) under the catalysis of residual ammonia molecules. After removing the (NH4)2SO4 cores and CTAB template by washing and extraction, the first layer of mesoporous silica was formed. (c) The second layer of mesoporous silica was fabricated by modulating the n-pentanol-water interface to n-hexane-water interface. Different hydrophobicity and swelling behavior of oil molecules leaded to gradient mesoporosity19,23. Finally, a gradient mesoporous hollow silica sheet was obtained.

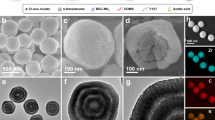

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were used to characterize the morphology and structure of (NH4)2SO4 crystals and mesoporous silica layers. As shown in Fig. 1a, the cuboid shape of (NH4)2SO4 crystals originates from the selective interaction between PVP and crystallographic planes. The high concentration of PVP distributed at the n-pentanol-water interface can be selectively absorbed on the {010} facets of (NH4)2SO4 crystals, which induced the formation of cuboid crystals24. The {011}, {110} and {010} facets of (NH4)2SO4 crystals can be clearly observed in the SEM image (Fig. 1a and Fig. S1). In the control experiments, no regular nanoparticles were formed when the dosage of PVP was decreased to 600 mg or when PVP was replaced with other amphiphilic molecules (Fig. S2), which further supported the crystal facet selectively preferential growth under high concentration of PVP25. As shown in Fig. 1b, the silica coated (NH4)2SO4 crystals were more uniformity compared with the pure (NH4)2SO4 cuboids, which was attributed to the coating of silica layers limited the growth of crystals. The mesoporous silica layers were obtained after washing and extraction to remove (NH4)2SO4 cores and CTAB template. Without the support of salt crystal, the first layer of mesoporous silica shell would shrink and flatten to a hollow sheet (Fig. 1c and Fig. S3). The hollow structure created by salt crystal can be further observed in the partially fractured regions of the silica sheets. The edge of silica sheets was crimped because of the ultrathin thickness (Fig. S4)26. The pore size on the first layer of mesoporous silica sheets was close to 2 nm, which was created by CTAB micelle. The deposited second layer of mesoporous silica reinforced the hollow sheet and possesses vertical mesopores with a pore size of about 6 nm (Fig. 1d)27. The CTAB micelle swelled by n-hexane leaded to the larger pore size. From the side view, the monodispersed hollow sheet structure can be clearly observed (Fig. 1d inset).

a SEM image of (NH4)2SO4 crystals. b SEM image of silica coated (NH4)2SO4 crystals. c TEM image of the first layer mesoporous silica sheets after removing (NH4)2SO4 cores and CTAB. d TEM images of the samples after coating the second layer of mesoporous silica. Inset is the side view of the samples.

The composition evolution of the products in different stages were monitored by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern and Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy. The formation of (NH4)2SO4 crystals were confirmed by XRD (Fig. S5). The diffraction peaks match well with orthorhombic (NH4)2SO4 (JCPDS No. 00-040-0660). The XRD diffraction pattern of silica layers (Fig. S6) exhibits a broad peak from 15 to 30° with a peak value at 22°, indicating the amorphous nature28. FT-IR spectra (Fig. 2a) of (NH4)2SO4 crystals shows peak at 1655 cm−1, correspond to the bond vibrations of C = O within PVP, which confirms the interaction of PVP and (NH4)2SO425. The FT-IR spectra of mesoporous silica layers (Fig. S7) shows that several typical absorption bands related to (NH4)2SO4, PVP and CTAB are basically eliminated compared with the silica-coated crystals before washing and extraction, which indicated the removal of salt cores and pore generators. The typical absorption band of mesoporous silica layers at 800 and 1100 cm−1 corresponded to the stretching vibration of Si-O-Si.

The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) has also been used for evaluating the thermal decomposition process of the samples. As shown in Fig. 2b and Fig. S8, three different weight loss ranges of the silica-coated crystals appeared during the thermal treatments: (i) the weight loss of 4% below 240 °C, which is due to the evaporation and release of water molecules and ammonia molecules. (ii) The dramatically weight loss of ∼39% (from 96 to 57%) appears from 240 to 380 °C, which is mainly ascribed to the thermolysis of CTAB and (NH4)2SO4. (iii) An obvious weight loss of ∼22% (from 57 to 35%) appears from 380 to 760 °C, which can be assigned to the thermal decomposition of PVP. The TGA data is consistent with the FT-IR results and supports the function of CTAB and PVP in the synthesis process.

Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms were measured to analyze the porosity of the obtained mesoporous silica sheets. As depicted in Fig. 2c, the sorption isotherms of the first layer mesoporous sheets exhibit characteristic type IV curves with a hysteresis loop in the pressure (P/P0) range of 0.4-0.9. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area and pore volume were calculated to be 380 m2 g−1 and 0.43 cm3 g−1 respectively which demonstrating the existence of mesopores29. The pore size distribution curve was derived from the adsorption branch and was calculated by the density functional theory pore size distribution (NLDFT) model. As presented in Fig. 2c inset, the pore size is mainly distributed at 2.2 nm, which is consistent with the TEM image (Fig. S4). After depositing the second layer of mesoporous silica, a higher BET surface area (913 m2 g−1) and pore volume (1.78 cm3 g−1) were obtained due to the increased amounts of mesopores (Fig. 2d). The low-angle X-ray diffraction pattern of the mesoporous silica sheet displays a broad diffraction peaks at 1.3° (Fig. S9), indicating uniform mesopores around 6 nm30, which is consistent with those observed in TEM image (Fig. 1d) and the calculated pore size distribution (the inset in Fig. 2d).

Molecule-level filtration plays a crucial part in industrial processes such as biomolecular purification, gas separation, and effluent treatment8,9,10. Benefiting from their sheet structure, appropriate pore size and superior mono-dispersity, the gradient mesoporous hollow silica sheet is a promising material for fabricating nanoscale molecule filtration device11,12,13. Here, a nanofiltration device was facilely fabricated by casting the mesoporous silica sheets dispersion over the cellulose membrane filter through vacuum filtration (Figs. S10–11). As shown in Fig. S12a, the cellulose membrane filter with 0.22 μm mesh-like macropores was served as a scaffold for the deposition of mesoporous silica sheets. Through vacuum filtration, the surface of cellulose membrane was covered with mesoporous silica sheets (Fig. S12c), and the original macroporous texture could not be observed. The fabricated nanofiltration device can be easily operated in the process of experiment. Surface wettability is an important parameter affecting nanofiltration molecular transport31. As depicted in Fig. 3a–c, the water contact angle of the nanofiltration device is close to 0°, indicating its excellent wettability and super hydrophilic features. The vertical porous channels, sheet structure and hydrophilic surface can minimize the flow resistance of water-soluble molecules, leading to a prominent water permeation flux (625 ± 20 L m−2 h−1 bar−1) (Fig. 3e)12,32.

a–c The water contact angle test procedure of the nanofiltration device. d Comparison to the nanofiltration device, the water contact angle of bare glass surface was 36.5o. e Permeation flux of the nanofiltration device compared with reported filtration materials33,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51. UV–vis absorption spectra of f MB, g RR, and h EB solutions before and after filtration through the nanofiltration device and pristine cellulose membrane. i Rejection performance of nanofiltration device and pristine cellulose membrane for dye molecules with different sizes. j Cycling tests of the nanofiltration device for EB filtration. k Nitrogen sorption isotherms of the regenerated mesoporous silica sheets. Inset is the corresponding TEM image.

The molecular filtration performance was evaluated by filtering molecules with different sizes (Fig. S13 and Table 1). Eight different dye solutions were chosen as feed materials and injected into the nanofiltration device, respectively31,33. The dye concentration in the feeds and permeate solutions were measured by UV–vis spectra. During the filtration process, water molecules and dye molecules smaller than 2.2 nm can pass through the porous channel smoothly under a gentle vacuum (≦0.04 MP) and capillary attraction20. As shown in Fig. S14 and Fig. 3f, adverse rejection rate (≦42.6%) were observed for Rhodamine B (RhB, 1.2 nm), Methylene blue (MB, 1.3 nm), and Rose bengal (RB, 1.5 nm). The Reactive red 120 (RR, 2.1 nm) and Congo red (CR, 2.5 nm) molecules, whose size are close to the 2.2 nm, can pass through the mesoporous silica layers with moderate rejection rate (≦57.5%, Fig. 3g and Fig. S14). For Evans blue (EB, 3.1 nm), Direct red 23 (DR23, 3.3 nm) and Direct red 80 (DR80, 4.4 nm), whose molecule size larger than 3 nm, the nanofiltration device can block almost all of the dyes with a high rejection rate (>99.0%, Fig. 3h and Fig. S14). As depicted in Fig. 3i, the removal rate of nanofiltration device increases gradually with the increase of molecular size, while for the pristine cellulose membrane, inferior removal rates (<20.0%) are observed for eight different dye molecules. The superior gradient rejection performance benefits from the narrow pore size distribution and sheet structure of mesoporous silica layers which enable precise size selection and secondary filtration possible12,21,22.

In addition, the reusability of the mesoporous silica sheets for nanoscale molecule filtration was further studied34,35. After filtration, the dye molecules on mesoporous silica surfaces and porous channels can be effectively removed by calcination at 600 °C in air. The regenerated mesoporous silica sheets were used for refabricating the nanofiltration device. Results demonstrated that even after multiple regenerate cycles (i.e. ≦5), the rejection rate for EB molecules was not significantly decreased (Fig. 3j). The excellent reusability benefits from good structural stability of the gradient mesoporous silica sheets. This can be further confirmed by the TEM and nitrogen adsorption-desorption analysis (Fig. 3k). The regenerated mesoporous silica sheets maintained structure integrity during the reuse cycles and the calculated BET surface area slightly decreases from 913 to 841 m2 g−1.

Conclusion

In summary, an interfacial co-assembly strategy for synthesizing gradient mesoporous hollow sheets is reported in this paper. In this method, the carefully selected oil-water interface enabled the formation of ammonium sulfate crystals and gradient mesoporous silica coatings. The mesoporous silica sheets have good prospects for nanoscale molecular filtration due to their sheet structure and appropriate pore size to maximize osmotic flux and enable precise species size control. Experiments reveal that the molecular removal rate of the fabricated nanofiltration device increases gradually with the increase of molecular size. This method provides a new way to prepare advanced functional porous materials with wide application fields.

References

Liu, J., Wickramaratne, N. P., Qiao, S. Z. & Jaroniec, M. Molecular-based design and emerging applications of nanoporous carbon spheres. Nat. Mater. 14, 763–774 (2015).

Yuan, G., Liu, D., Feng, X. & Zhang, Y. 3D carbon networks: design and applications in sodium ion batteries. ChemPlusChem 86, 1135–1161 (2021).

Kankala, R. K. et al. Nanoarchitectured structure and surface biofunctionality of mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 32, 1907035 (2020).

Li, W., Liu, J. & Zhao, D. Mesoporous materials for energy conversion and storage devices. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16023 (2016).

Li, C. et al. Self-assembly of block copolymers towards mesoporous materials for energy storage and conversion systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 4681–4736 (2020).

Liu, S. H. et al. Patterning two-dimensional free-standing surfaces with mesoporous conducting polymers. Nat. Commun. 6, 8817 (2015).

Lv, H. et al. Asymmetric multimetallic mesoporous nanospheres. Nano Lett. 19, 3379–3385 (2019).

Li, X., Younas, M., Rezakazemi, M., Ly, Q. V. & Li, J. A review on hollow fiber membrane module towards high separation efficiency: process modeling in fouling perspective. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33, 3594–3602 (2022).

Liu, Y. P. et al. Mesoporous silica thin membranes with large vertical mesochannels for nanosize-based separation. Adv. Mater. 29, 1702274 (2017).

Gao, X., Zou, X., Ma, H., Meng, S. & Zhu, G. Highly selective and permeable porous organic framework membrane for CO2 capture. Adv. Mater. 26, 3644–3648 (2014).

Duan, L. L. et al. Synthesis of fully exposed single-atom-layer metal clusters on 2D ordered mesoporous TiO2 nanosheets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202211307 (2022).

Yuan, G. B. et al. In situ fabrication of porous CoxP hierarchical nanostructures on carbon fiber cloth with exceptional performance for sodium storage. Adv. Mater. 34, 2108985 (2022).

Zou, X. & Zhu, G. Microporous organic materials for membrane-based gas separation. Adv. Mater. 30, 1700750 (2018).

Wu, Z. Y., Liang, H. W., Chen, L. F., Hu, B. C. & Yu, S. H. Bacterial cellulose: a robust platform for design of three dimensional carbon-based functional nanomaterials. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 96–105 (2016).

Gao, Y. F. et al. Nanoceramic VO2 thermochromic smart glass: a review on progress in solution processing. Nano Energy 1, 221–246 (2012).

Marichy, C., Bechelany, M. & Pinna, N. Atomic layer deposition of nanostructured materials for energy and environmental applications. Adv. Mater. 24, 1017–1032 (2012).

Li, C. L. et al. Electrochemical deposition: an advanced approach for templated synthesis of nanoporous metal architectures. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 1764–1773 (2018).

Walcarius, A. Mesoporous materials and electrochemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 4098 (2013).

Shen, D. K. et al. Biphase stratification approach to three-dimensional dendritic biodegradable mesoporous silica nanospheres. Nano Lett. 14, 923–932 (2014).

Hung, C. T. et al. Gradient hierarchically porous structure for rapid capillary-assisted catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 6091–6099 (2022).

Liu, Y. P. et al. Ultrahigh adsorption capacity and kinetics of vertically oriented mesoporous coatings for removal of organic pollutants. Small 17, 2101363 (2021).

Yadav, A., Labhasetwar, P. K. & Shahi, V. K. Fabrication and optimization of tunable pore size poly (ethylene glycol) modified poly(vinylidene-co-hexafluoropropylene) membranes in vacuum membrane distillation for desalination. Separ. Purif. Technol. 271, 118840 (2021).

Han, L. et al. Synthesis and characterization of macroporous photonic structure that consists of azimuthally shifted double-diamond silica frameworks. Chem. Mater. 26, 7020–7028 (2014).

Yang, Y. et al. Synthesis and assembly of colloidal cuboids with tunable shape biaxiality. Nat. Commun. 9, 4513 (2018).

Xiong, H. L. et al. Polymer stabilized droplet templating towards tunable hierarchical porosity in single crystalline Na3V2(PO4)3 for enhanced sodium-ion storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 10334–10341 (2021).

Im, H. G. et al. Hybrid crystalline-ITO/metal nanowire mesh transparent electrodes and their application for highly flexible perovskite solar cells. NPG Asia Mater. 8, e282 (2016).

Gao, W. et al. Preparation microstructure and mechanical properties of steel matrix composites reinforced by a 3D network TiC ceramic. Ceram. Int. 48, 20848–20857 (2022).

Feng, D. Y. et al. A general ligand-assisted self-assembly approach to crystalline mesoporous metal oxides. NPG Asia Mater. 10, 800–809 (2018).

Zhang, L. L. et al. Multistage self-assembly strategy: designed synthesis of N-doped mesoporous carbon with high and controllable pyridine N content for ultrahigh surface-area-normalized capacitance. CCS Chem. 2, 870–881 (2020).

Zhou, W. W. et al. Hydrodesulfurization of 4,6-dimethyldibenzothiophene over NiMo sulphide catalysts supported on meso-microporous Y zeolite with different mesopore sizes. Appl. Catal. B. 238, 212–224 (2018).

Yang, J., Lin, G. S., Mou, C. Y. & Tung, K. L. Mesoporous silica thin membrane with tunable pore size for ultrahigh permeation and precise molecular separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 7459–7465 (2020).

Zou, X. Q. et al. Effective heavy metal removal through porous stainless-steel-net supported low siliceous zeolite ZSM-5 membrane. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 124, 70–75 (2009).

Jiang, M. et al. Conventional ultrafiltration as effective strategy for dye/salt fractionation in textile wastewater treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 10698–10708 (2018).

El-Safty, S. A., Shahat, A. & Mekawy, M. Large three-dimensional mesocage pores tailoring silica nanotubes as membrane filters: nanofiltration and permeation flux of proteins. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 5593–5603 (2011).

Lin, X., Yang, Q., Ding, L. & Su, B. Ultrathin silica membranes with highly ordered and perpendicular nanochannels for precise and fast molecular separation. ACS Nano 9, 11266–11277 (2015).

Cheng, X. Q., Shao, L. & Lau, C. H. High flux polyethylene glycol based nanofiltration membranes for water environmental remediation. J. Membr. Sci. 476, 95–104 (2015).

Lohokare, H. R., Chaudhari, H. D. & Kharul, U. K. Solvent and pH-stable poly (2, 5-benzimidazole) (ABPBI) based UF membranes: preparation and characterizations. J. Membr. Sci. 563, 743–751 (2018).

Fang, W., Shi, L. & Wang, R. Interfacially polymerized composite nanofiltration hollow fiber membranes for low-pressure water softening. J. Membr. Sci. 430, 129–139 (2013).

Yang, Z. et al. Tannic acid/Fe3+ nanoscaffold for interfacial polymerization: toward enhanced nanofiltration performance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 9341–9349 (2018).

Homayoonfal, M., Akbari, A. & Mehrnia, M. R. Preparation of polysulfone nanofiltration membranes by UV-assisted grafting polymerization for water softening. Desalination 263, 217–225 (2010).

Werber, J. R., Porter, C. J. & Elimelech, M. A path to ultraselectivity: support layer properties to maximize performance of biomimetic desalination membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 10737–10747 (2018).

Martín, A., Arsuaga, J. M., Roldan, N., Martínez, A. & Sotto, A. Effect of amine functionalization of SBA-15 used as filler on the morphology and permeation properties of polyethersulfone-doped ultrafiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 520, 8–18 (2016).

Peng, L., Xu, X., Yao, X., Liu, H. & Gu, X. Fabrication of novel hierarchical ZSM-5 zeolite membranes with tunable mesopores for ultrafiltration. J. Membr. Sci. 549, 446–455 (2018).

Pereira, B. D. et al. Water permeability increase in ultrafiltration cellulose acetate membrane containing silver nanoparticles. Mater. Res. 20, 887–891 (2017).

Chen, X. F. et al. Enhanced performance arising from low-temperature preparation of α-alumina membranes via titania doping assisted sol-gel method. J. Membr. Sci. 559, 19–27 (2018).

Holland, M. C. et al. Facile post processing alters the permeability and selectivity of microbial cellulose ultrafiltration membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 13249–13256 (2020).

Zhang, W. N. et al. Ultrathin nanoporous membrane fabrication based on block copolymer micelles. J. Membr. Sci. 570-571, 427–435 (2019).

Pandey, R. P. et al. Enhanced water flux and bacterial resistance in cellulose acetate membranes with quaternary ammoniumpropylated polysilsesquioxane. Chemosphere 289, 133144 (2022).

Bi, R., Zhang, Q., Zhang, R., Su, Y. & Jiang, Z. Thin film nanocomposite membranes incorporated with graphene quantum dots for high flux and antifouling property. J. Membr. Sci. 553, 17–24 (2018).

Fan, H., Gu, J., Meng, H., Knebel, A. & Caro, J. High-flux imine linked covalent organic framework COF-LZU1 membranes on tubular alumina supports for highly selective dye separation by nanofiltration. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 4083–4087 (2018).

Zhu, J. et al. Elevated salt transport of antimicrobial loose nanofiltration membranes enabled by copper nanoparticles via fast bioinspired deposition. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 13211–13222 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21671073, 21621001, and 22105033), the “111” Project of the Ministry of Education of China (B17020), the Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Plan (YDZJ202101ZYTS137), and Program for JLU Science and Technology Innovative Research Team, Interdisciplinary Integration and Innovation Project of Jilin University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.A.Q. and F.W. designed the experiments. Y.B.D. performed all the experiments and wrote the manuscript. D.Y.F. modified the manuscript. W.L. and S.Z.D. discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. R.Z. contributed to the Scheme 1. L.Q.W. and Y.Y. carried out the TEM and SEM imaging. L.W. investigated the effect of particle morphology on filtration performance and contributed to the thermogravimetric analysis in the revised manuscript. Y.Y. carried out the TEM and SEM imaging in the revised manuscript and reviewed the response to reviewers.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, Y., Feng, D., Li, W. et al. Interfacial co-assembly strategy towards gradient mesoporous hollow sheet for molecule filtration. NPG Asia Mater 15, 53 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-023-00500-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-023-00500-0