Abstract

We report a giant spin-orbit torque (SOT) induced by spin Hall effect (SHE) in amorphous Pt(P) alloys, which is confirmed by magnetization switching and spin torque-ferromagnetic resonance measurements. Pt(P) is fabricated by ion-implantation technique using energies from 10 to 30 keV with doses ranging from 2.5 × 1016 to 10 × 1016 ions/cm2. The P-ion implantation process causes distortion and defects in the fcc structure of the as-deposited Pt layer and changes it to an amorphous structure as the accelerating energy as well as the dose increases, leading to a decrease in the electrical conductivity. However, we can obtain a higher spin Hall conductivity, \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\) of \(3.62\times {10}^{3}\frac{\hslash }{2e}{\Omega }^{-1}{\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\) for Pt(P) as compared to that of \(1.03\times {10}^{3}\frac{\hslash }{2e}{\Omega }^{-1}{\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\) for pure Pt. The spin Hall efficiency, \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) is drastically increased up to 1.17 for Pt(P) with 30 keV energy and dose of 7.5 × 1016 ions/cm2. We also observe a significant reduction in the critical switching current density, \({J}_{{\rm{sw}}}\) of the SOT magnetization switching from 1.5 × 1011 A/m2 for pure Pt to 3.0 × 1010 A/m2 for Pt(P). Such a giant SHE can reduce the power consumption to control the magnetization by using SOT, and therefore our findings may provide an alternate path to enhance \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) by using amorphous materials with a variety of elements, beyond crystalline solids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Current induced spin-orbit torque (SOT) arising from the spin Hall effect (SHE)1,2, or the Rashba-Edelstein effect (REE)3,4, has been at the forefront of spintronics in the designing of memory and logic devices for controlling the magnetization in the magnetic layer5,6. The strength of this SOT is quantified by the spin Hall efficiency, \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\), defined as the amount of spin current density \({{\boldsymbol{j}}}_{{\bf{s}}}\), generated from the charge current density, \({{\boldsymbol{j}}}_{{\bf{c}}}\) in the SHE or the REE layer, which then exerts an in-plane damping like torque, \({\tau }_{{\rm{DL}}}\) on the magnetization \(\hat{m}\) of the magnetic layer. In this regard, the relation between \({{\boldsymbol{j}}}_{{\bf{s}}}\), \({{\boldsymbol{j}}}_{{\bf{c}}}\) and \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) can be given as \({{\boldsymbol{j}}}_{{\bf{s}}}=\frac{\hslash }{2e}{\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}({{\boldsymbol{j}}}_{{\bf{c}}}\times \hat{\sigma })\), where \(\hat{\sigma }\) is polarization of spin current, \(e\) is the electronic charge and \(\hslash\) is the reduced Planck constant7. \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{DL}}}\) is proportional to \(\hat{m}\times (\hat{\sigma }\times \hat{m})\)8\(,\) meaning that stronger the \({\tau }_{{\rm{DL}}}\), higher is the \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\). Typically, \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) has been widely explored in 5 d transition metals with strong spin-orbit coupling (SOC) via intrinsic scattering, such as Pt, Ta and W6,7. Alternatively, \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) has also been studied by alloying lighter elements such as Al and Pd with Os, Ir and Pt via extrinsic scattering9, as well as in 5 d transition metal oxides like IrO210. However, \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) is restricted to low values and/or higher longitudinal resistivity, \({\rho }_{{\rm{xx}}}\) of 5 d transition metals, alloys and oxides, curtailing their practical applications in low power consumption in SOT magnetic random-access memory (SOT-MRAM), as it relies heavily on the ratio of \({\rho }_{{\rm{xx}}}/{\theta }_{{SH}}^{2}\)11\(.\) Moreover, reducing the critical switching current density, \({J}_{{\rm{sw}}}\) for magnetization switching is imperative to make the SOT-MRAM endurable to large current operations and thermal fluctuations12,13.

Recently, ion-implantation or irradiation-based engineering has been used for tuning the \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) via lighter impurities such as sulfur (S)14, oxygen (O)15, and nitrogen (N)16 implanted in the host Pt layer. To study the extrinsic mechanism of SHE, in general, light metals such as Cu and Al are used as the host material and the impurity scattering with strong SOC is investigated by doping an element with large atomic number5,8,9. On the other hand, the intrinsic mechanism, relies on the Berry curvature of the momentum of conduction electrons in a material, and is largely found in 5 d transition metals with a strong SOC. Therefore, for doping S, O and N in Pt, electrons are scattered by their impurity potential and then the spin dependent scattering is caused by SOC in the host Pt, which leads to an increase in \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) up to 0.23, as compared to \(\approx\)0.04–0.09 for pure Pt, at room temperature. In these irradiation processes, a low irradiation energy of 12 keV and 20 keV for S and O, N, respectively, were used, and thus no significant change was observed in the crystallographic property of the host Pt layers14,15,16. However, under a high irradiation energy condition, vacancies, interstitial atoms, and atomic displacements occur and then the cores of displacement cascades are available to produce phase changes and structural alternations, which are otherwise not observed in thermal equilibrium condition17. Systematic studies on SHE induced SOT and magnetization switching in materials with defects and vacancies of this nature, are found to be lacking.

In this article, we study the SHE by introducing a new lighter impurity, phosphorus (P) into host Pt, i.e., Pt(P) fabricated by the ion-implantation technique using an energy of 10–30 keV with fluence/dose ranging from 2.5 × 1016 to 10 × 1016 ions/cm2. The ion-implantation process causes distortion and defects in the fcc structure of Pt and changes it to an amorphous structure as the accelerating potential as well as the dose are increased. Such a change leads to a decrease in the electrical conductivity, \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xx}}}\) due to the defects created by P-ion implantation. Despite the decrease in \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xx}}}\), we observe a significant reduction in SOT switching current density, \({J}_{{\rm{sw}}}\) from 1.5 × 1011 A/m2 for Pt/GdFeCo to 3.0 × 1010 A/m2 for Pt(P)/GdFeCo. To further confirm and determine the enhanced \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\), we perform spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance (ST-FMR) based lineshape (LS) and linewidth (LW) analysis measurements of Pt(P)/NiFe. We observe a giant \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) up to 1.17 for Pt(P) with 30 keV energy and dose of 7.5 × 1016 ions/cm2, which is 34-times higher than the \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) of 0.034 for pure Pt, due to the extrinsic scattering from impurities. Furthermore, due to the controlled trade-off in \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) and \({\rho }_{{\rm{xx}}}\), we obtain a higher spin Hall conductivity, \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\) of \(3.62\times {10}^{3}\frac{\hslash }{2e}{\Omega }^{-1}{\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\), which is higher than state-of-the-art samples of IrAl and OsAl with a value of \(1.5\times {10}^{3}\frac{\hslash }{2e}{\Omega }^{-1}{\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\) and \(1.3\times {10}^{3}\frac{\hslash }{2e}{\Omega }^{-1}{\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\), respectively9. Due to this higher \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\) as well as \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\), we can obtain a lower power consumption ratio, \({\rho }_{{\rm{xx}}}/{\theta }_{{SH}}^{2}\) for Pt(P), in comparison to metals such as Pt, Ta, W, our previous ion-implantation materials of Pt(S), Pt(O), and Pt(N), and also the IrAl and OsAl alloys.

Results

Spin-orbit torque driven magnetization switching measurements

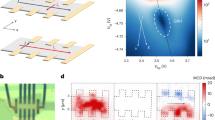

We realize perpendicular magnetization switching of the ferrimagnetic rare earth (RE)- transition metal (TM) alloy GdFeCo (10 nm), using the SOT generated from the Pt layer or the Pt(P) layer. When measuring the Hall voltage \({{V}_{\rm{Hall}}}\) under an out-of-plane external field sweep, we obtain square hysteresis loops for both Pt/GdFeCo and Pt(P)/GdFeCo (see Fig. 1a and Supplementary Information S1 for Polar Magneto-Optic Kerr effect (PMOKE) measurements), confirming the perpendicular magnetic anisotropy (PMA) of the GdFeCo layer18,19. The polarity of the measured signal indicates that the GdFeCo is TM-dominated with a coercivity of 10 mT. The magnitude of the anomalous Hall voltage of Pt(P)/GdFeCo is drastically increased at the same applied current of 1 mA to the samples because the resistance of the Pt(P) increases, and thus a higher current passes through the GdFeCo layer. A schematic illustration of the measurement set-up for performing SOT driven magnetization switching is shown in Fig. 1b. The magnetization was initialized along the z axis by applying an out-of-plane external field of 100 mT. After initialization, direct current (DC), \({{I}_{\rm{DC}}}\) of different magnitudes were swept along the current channel in the presence of a fixed external field along the x-direction. The polarity of the magnetic field determines the sense of switching achieved19. Under a positive (negative) external field, a(n) (anti) clockwise sense of switching can be observed. The critical switching current \({{{I}}}_{{\rm{sw}}}\) is defined as that current at which \({{V}_{\rm{Hall}}}\) changes its polarity in Fig. 1c. The critical switching current density \({{\boldsymbol{J}}}_{{\bf{sw}}}\) was found to decrease from 1.5 × 1011 A/m2 for Pt/GdFeCo to 3.0 × 1010 A/m2 for Pt(P)/GdFeCo. It should be noted that one order smaller \({{\boldsymbol{J}}}_{{\bf{sw}}}\) of ~ 1010 A/m2 for Pt(P)/GdFeCo is confirmed for different magnitudes and polarities of the external field Hx, as shown in Fig. 1d. The observed asymmetric switching behavior may be attributed to several possible reasons such as Joule heating, edge domains nucleated under electrode pads20, tilted uniaxial magnetic anisotropy21, etc. The possible underlying mechanism for such asymmetric switching is still under investigation13. Furthermore, we also obtain a 4 times smaller switching energy density, \({{{U}}}_{{\rm{sw}}}\) for Pt(P) as compared to Pt, due to the enhancement in SOT induced by SHE (see Supplementary Information S2). Therefore, the reasonable \({{\boldsymbol{J}}}_{{\bf{sw}}}\) of ~ 1011 A/m2 and lower \({{{U}}}_{{\rm{sw}}}\) for Pt/GdFeCo suggests that the magnetization switching is mainly caused by SOT and therefore the low \({{\boldsymbol{J}}}_{{\bf{sw}}}\) of ~ 1010 A/m2 for Pt(P)/GdFeCo is attributed to an increase of SHE of Pt(P).

a Hall voltage loops for Pt/GdFeCo and Pt(P)/GdFeCo under an out-of-plane field sweep. b Schematic diagram showing the setup for switching measurement under current sweep. c Hall voltage as a function of current density through the Pt or Pt (P) layer, in the presence of a fixed external field \({\mu }_{0}{H}_{{\rm{x}}}\) = + 10 mT. d Critical switching current density \({J}_{{\rm{sw}}}\) as a function of the external in-plane field \({H}_{{\rm{x}}}\), for both Pt/GdFeCo and Pt(P)/GdFeCo.

Spin torque-ferromagnetic resonance measurements

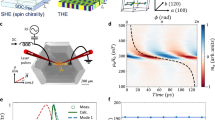

To study the effect of P ion implantation in the Pt layer on the SHE, we measure \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) using two methods of spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance (ST-FMR) measurements (see Materials and Methods for details), i.e., lineshape (LS) analysis and linewidth (LW) analysis (DC-bias ST-FMR)7. For the ST-FMR measurements, NiFe (5 nm) was deposited on top of the Pt(P) layer. The schematic of the ST-FMR measurement set-up is shown in Fig. 2a. In this measurement technique, \({I}_{{\rm{rf}}}\) with microwave frequencies (\(f\)) ranging from 5 to 11 GHz was applied to the Pt(P) layer along the x-axis using a signal generator with an applied power of 5 dBm. An external in-plane magnetic field \({\mu }_{{\rm{o}}}{H}_{{\rm{ext}}}\), was swept from −200 mT to +200 mT at an angle of \(\phi\) = 45ο with respect to \({I}_{{\rm{rf}}}\). Due to \({I}_{{\rm{rf}}}\), i.e., the \({{\boldsymbol{j}}}_{{\bf{c}}}\) along x-axis, y-polarized spins are generated in Pt(P) due to SHE, which travel upwards as \({{\boldsymbol{j}}}_{{\bf{s}}}\) along the z-axis, to NiFe and exert an-in plane damping-like torque, \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{DL}}}(\propto \hat{m}\times \hat{\sigma }\times \hat{m})\) on the magnetization \(\hat{m}\) of NiFe. Simultaneously, the Oersted field \(({h}_{{\rm{rf}}})\) generated from the \({I}_{{\rm{rf}}}\) along y-axis exerts an out-of-plane Oersted field torque, \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{OF}}}\left(\propto \hat{m}\times {h}_{{\rm{rf}}}\right)\). Furthermore, an out-of plane field-like torque \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{FL}}}\left(\propto -(\hat{\sigma }\times \hat{m}\right))\) may also arise and overlap with \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{OF}}}\). Fundamentally, both bulk and interface effects can give rise to these torques, \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{DL}}}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{FL}}}\), with the former emanating from SHE, and the latter from REE. In the case of negligible or less dominant \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{FL}}}\), the combined torques (\({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{DL}}}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{OF}}}\)) drive the magnetization precession in NiFe, yielding a time dependent change of the anisotropic magnetoresistance \(\Delta R\) of NiFe and upon satisfying the FMR condition, produces an output ST-FMR voltage due to periodic mixing of the change in magnetoresistance \(\Delta R\) of NiFe and \({I}_{{\rm{rf}}}\). The ST-FMR voltage here is the low frequency voltage with the \({I}_{{\rm{rf}}}\) being amplitude modulated by a low frequency sinusoidal signal of 79 Hz which is provided as a reference signal into the reference port of lock-in amplifier22,23. Figure 2b shows the ST-FMR (spectrum) voltage obtained at f = 5 GHz at \({I}_{{\rm{dc}}}\) = 0 mA for Pt/NiFe and Pt(P)/NiFe expressed as:

where, \({F}_{\mathrm{sym}}\left({H}_{\mathrm{ext}}\right)=\frac{{\left(\Delta H\right)}^{2}}{{({H}_{\mathrm{ext}}-{H}_{{\rm{o}}})}^{2}+{\left(\Delta H\right)}^{2}}\) is the symmetric part, and \({F}_{{\rm{a}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{y}}{\rm{m}}}({H}_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{x}}{\rm{t}}})=\frac{\Delta H({H}_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{x}}{\rm{t}}}-{H}_{{\rm{o}}})}{{({H}_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{x}}{\rm{t}}}-{H}_{{\rm{o}}})}^{2}+{(\Delta H)}^{2}}\) is the antisymmetric part, \(\Delta H\) and \({H}_{{\rm{o}}}\) are the linewidth and resonance field of FMR spectra, while S and A are the weight factors of the symmetric and antisymmetric part, respectively. For the ST-FMR spectra, the weight factor of the symmetric (S) component arises from \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{DL}}}\), while the weight factor of the antisymmetric (A) component is mainly dominated by \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{OF}}}\). Noticeably, a giant symmetric component \(({{\rm{S}}F}_{{\rm{sym}}}\left({H}_{{\rm{ext}}}\right))\) is observed for Pt(P)/NiFe in comparison to Pt/NiFe as shown in Fig. 2b. To quantify the \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{DL}}}\) in terms of \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) using the lineshape (LS) analysis, \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LS}}}\), we utilize the self-calibrated ratio of S/A given by7:

where \({\mu }_{{\rm{o}}}\) is the permeability of free space, \({M}_{{\rm{s}}}\) is the saturation magnetization of NiFe, \(t\) is NiFe thickness, \(d\) is Pt(P) thickness, and \({M}_{{\rm{eff}}}\) is the effective demagnetization field obtained from Kittel fitting23,24. The obtained \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LS}}}\) values for Pt/NiFe and Pt(P)/NiFe are 0.034 and 0.750, respectively. Figure 2c shows \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LS}}}\) as a function of the applied microwave frequency \(f\). \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LS}}}\) being independent of \(f\) implies a negligible role of thermal effect and uncontrolled relative phase between \({I}_{{\rm{rf}}}\) and \({h}_{{\rm{rf}}}\) that arises from sample design25.

a Schematic showing ST-FMR measurement technique and detection principle for Pt(P)/NiFe, along with an optical image of the micro-device. b ST-FMR voltage \({V}_{{\rm{mix}}}\) obtained at f = 5 GHz with the de-convoluted symmetric and antisymmetric component fitted using Eq. (1) for Pt/NiFe and Pt(P)/NiFe. c \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LS}}}\) plotted as a function of \(f\) for Pt/NiFe and Pt(P)/NiFe.

The LS analysis at a confined angular range of \(\phi\) = 45ο that hinges on the conjecture of S/A being invariant with \(\phi\) may not divulge the complete visualization of SOT. Therefore, it is imperative to perform an in-plane angular dependence of the ST-FMR lineshape22,26, to rule out the artefacts and unconventional torques present in the system as independently demonstrated by Skinner27 and later revisited by Sklenar et al.28. Figure 3a, b shows the weight factors of S and A components well fitted with the dominant \(\sin 2\phi \cos \phi\) behaviour for Pt/NiFe and Pt(P)/NiFe. SHE exhibits a \(\cos \phi\) dependence in both S and A components and combined with \(\sin 2\phi\) arising from the AMR of NiFe, it subsequently yields a dominant \(\sin 2\phi \cos \phi\) behaviour. The linewidth (LW) modulation (or the modulation of effective damping, \({\alpha }_{{\rm{eff}}}\)) using DC-bias ST-FMR is an additional method to circumvent issues such as spin pumping contribution in the symmetric component of \({V}_{{\rm{mix}}}\) obtained via LS analysis29, broken two-fold and mirror symmetry of torques due to unconventional SOT30, and the inaccuracy in estimating \({\theta }_{{\rm{DL}}}\) from LS due to interfacial REE31. Hence, in linewidth (\(\Delta H\)) modulation, a DC current (\({I}_{{\rm{dc}}}\)) is applied along with \({I}_{{\rm{rf}}}\) in the same set-up, as shown in Fig. 2a to overcome these issues. Upon changing the polarity of \({H}_{{\rm{ext}}}\), we observe a reversed slope of \({\alpha }_{{\rm{eff}}}\), defined as \({\alpha }_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{f}}{\rm{f}}}=\gamma /2\pi f({\mu }_{{\rm{o}}}\Delta H-{\mu }_{{\rm{o}}}\Delta {H}_{{\rm{o}}})\). By reversing the polarity of \({H}_{{\rm{ext}}}\) from (\(+{H}_{{\rm{ext}}}\)) \(\phi\) = 45ο to (\(-{H}_{{\rm{ext}}})\) \(\phi\) = 225ο, NiFe magnetizes in the opposite direction, thereby leading to a reversed polarity of \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{DL}}}\). This subsequently results in a reversal in the slope of \(\frac{\Delta {\alpha }_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{f}}{\rm{f}}}}{\Delta {j}_{{\rm{d}}{\rm{c}}}}\) upon changing the polarity of \({H}_{{\rm{ext}}}\), as shown in Fig. 3c, d for Pt/NiFe and Pt(P)/NiFe, respectively. Accordingly, by utilizing the slope of \(\frac{\Delta {\alpha }_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{f}}{\rm{f}}}}{\Delta {j}_{{\rm{d}}{\rm{c}}}}\), the spin Hall efficiency is evaluated from modulation of linewidth, \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LW}}}\) is given as7:

Noticeably, a higher slope is observed for Pt(P)/NiFe, depicting a higher \({\theta }_{{\rm{DL}}}^{{\rm{LW}}}\) compared to Pt/NiFe, in Fig. 3c, d. \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LW}}}\approx 0.761\) is obtained for Pt(P), which is \(\approx\)16 times higher than for Pt (\({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LW}}}\approx 0.045\)).

As discussed earlier, there may be \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{FL}}}\) arising from interfacial REE which can overlap with \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{OF}}}\) in the lineshape analysis. Therefore, to rule out the presence of \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{FL}}}\) in Pt(P), the \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LS}}},{\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LW}}}\) and \({\theta }_{{\rm{FL}}}\) can be correlated as31:

where \({\theta }_{{\rm{FL}}}\) is field-like torque efficiency from \({\tau }_{{\rm{FL}}}\). We obtain \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LS}}}\approx\) 0.034 and \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LW}}}\approx\) 0.045 for Pt, \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LS}}}\approx\) 0.750 and \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LW}}}\approx\) 0.761 for Pt(P). The similar values of \({\theta }_{{\rm{DL}}}^{{\rm{LS}}}\) and \({\theta }_{{\rm{DL}}}^{{\rm{LW}}}\) implies that \({\theta }_{{\rm{FL}}}\) is insignificant for Pt(P). Consequently, the obtained \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LS}}}\) and \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}^{{\rm{LW}}}\) are attributed to conventional \({{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}_{{\bf{DL}}}\) acting on the magnetization of NiFe due to \({j}_{{\rm{s}}}\) generated from bulk SHE.

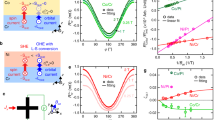

Spin Hall efficiency, spin Hall conductivity, and power consumption

Figure 4 shows \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) as a function of \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xx}}}\) for all the samples evaluated in this study. Note that the P composition in Pt(P) could be lower for smaller accelerating potential (10–20 keV) due to the protective MgO/Al2O3 layers, which decelerates the diffusion of P ions into the Pt layer as compared to 30 keV (see supplementary information S3 for SRIM simulations). The conductivity of Pt(P) is strongly affected by the accelerating potential and the dose of P ions. Additionally, \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) of Pt(P) increases with decreasing \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xx}}}\), as can be seen in Fig. 4. Here, the \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\) is defined as \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}={\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\times {\sigma }_{{\rm{xx}}}\). Interestingly, we do not observe a linear relation between \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) and \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xx}}}\), hinting at the \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\) following a non-linear scaling with \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xx}}}\), as seen in our previous work for the ion-implantation samples14,15,16. Such a non-linear scaling of \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\) with \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xx}}}\), i.e., \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\propto {\sigma }_{{\rm{xx}}}^{1.6-1.8}\) or \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\propto {\sigma }_{{\rm{xx}}}^{2}\), can arise from co-existence of intrinsic and spin-dependent extrinsic scattering from impurities16,23. For Pt(P) with \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) > 0.5, defect and void accumulation in the Pt(P) layer during the ion implantation process causes amorphization (please see supplementary information S4, S5, S6 for XRD, HAADF-STEM, XAS measurements, respectively). Therefore, due to the presence of these defects and voids, we may not apply a simple scaling model of \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\) with \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xx}}}\), for the Pt(P) alloys, and would require further investigations and future work. However, an important finding is that the largest \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) are found at higher P-doses where the structure loses its crystalline texture and transitions to amorphous nature. In the case of IrO2, the crystallographic properties (polycrystalline or amorphous nature) do not affect \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\), as shown in Fig. 5a. Recently, topological insulators (TIs) are proposed theoretically in amorphous materials32,33, and large anomalous Hall effect (AHE) has been experimentally reported in amorphous films34. Since AHE and SHE share the same analogy, such a giant SHE in amorphous Pt(P) may be an exciting research direction, in addition to these previous theoretical and experimental reports. Interestingly, such a modification of crystallographic properties does not adversely affect the SOC, and therefore, the impurity scattering of P which is a light element can cause a spin-dependent extrinsic scattering via its SOC of Pt and generate the giant spin current in Pt(P). Therefore, our findings provide an alternative path to enhance \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) by using amorphous materials, beyond crystalline solids.

Figure 5a shows \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\) as a function of \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xx}}}\) for all the samples evaluated in this study compared with other 5 d transition metals, alloys, oxides and other ion-implanted Pt such as Pt(S), Pt(O) and Pt(N). For Pt(P) with \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) < 0.5, low energies of 10–15 keV are not sufficient to cause amorphization, however, the extrinsic SHE can enhance \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\), which is comparable to our previous results of Pt(S) fabricated at 12 keV and Pt(O) and Pt(N) fabricated at 20 keV14,15,16. For Pt(P) with \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) lying between 0.5 and 1, i.e., 0.5 \(< \,{\theta }_{{\rm{S}}{\rm{H}}}\) < 1, moderate energies of 20–30 keV are enough to cause amorphization, leading to a giant \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\) of \(3.62\times {10}^{3}\frac{\hslash }{2e}{\Omega }^{-1}{\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\), which is higher than the state-of-the-art samples of IrAl and OsAl with a value of \(1.5\times {10}^{3}\frac{\hslash }{2e}{\Omega }^{-1}{\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\) and \(1.3\times {10}^{3}\frac{\hslash }{2e}{\Omega }^{-1}{\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\), respectively9. Finally, for \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) > 1, i.e, 1.17, it is higher than 5 d transition metals and their alloys, and quite useful for low power consumption in SOT-MRAM, which we explore next.

Figure 5b shows \({\rho }_{{\rm{xx}}}/{\theta }_{{SH}}^{2}\) as a function of \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xx}}}\) for all the samples evaluated in this study. For Pt(P) with \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) < 0.5, i.e., the low energy 10–15 keV samples, the power consumption factor is moderate. It is comparable to that of our ion-implantation samples, Pt(S), Pt(O) and Pt(N). Nevertheless, it is lower than oxides such as amorphous-IrO2 (a-IrO2) and polycrystalline-IrO2 (p-IrO2). For Pt(P) with \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) lying between 0.5 and 1, i.e., 0.5 \(< \,{\theta }_{{\rm{S}}{\rm{H}}}\) < 1, moderate energies of 20–30 keV, power consumption is better than PdPt and our previous ion-implanted samples of Pt(S), Pt(O), Pt(N). The actual benchmark is achieved for Pt(P) with \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) > 1, i.e., \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) = 1.17, when it has the lowest power consumption to materials in our knowledge. It is noteworthy to mention that despite the considerable \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) in TIs11,34,35, the enhanced energy dissipation due to current shunting from a larger \({\rho }_{{\rm{xx}}}\) makes the overall ratio of \({\rho }_{{\rm{xx}}}/{\theta }_{{SH}}^{2}\) higher, making it energetically unfavourable for SOT-MRAM. Therefore, our Pt(P) not only reduces the \({J}_{{\rm{sw}}}\) for PMA magnetization switching, which can be useful in SOT-MRAM, but it also leads to a giant SHE which is not dependent on the ferromagnetic material, propelling it to be indispensable in modern spintronics.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we report a systematic study of the giant SHE in Pt(P) layers, fabricated by P-ion implantation, with varying acceleration energies of 10–30 keV and doses of 2.5 × 1016 to 10.0 × 1016 ions/cm2. The ion implantation process causes distortion and defects, leading to amorphization of the Pt layer, confirmed by XRD, HAADF-STEM, and XAS measurements. We confirm \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\), by ST-FMR based LS and LW analysis measurements, and find it to be up to 1.17 for Pt(P), which is 34-times higher than the \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) of 0.034 for pure Pt. Furthermore, we confirm the \(\sin 2\phi \cos \phi\) behaviour via the in-plane angular dependence of the ST-FMR lineshape, depicting the bulk and conventional nature of SHE. Furthermore, we obtain a higher \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\) of \(3.62\times {10}^{3}\frac{\hslash }{2e}{\Omega }^{-1}{\mathrm{cm}}^{-1}\) for Pt(P) with ion dose of 7.5 × 1016 ions/cm2 at acceleration energy of 30 keV. Due to this higher \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\), we obtain a lower power consumption ratio, \({\rho }_{{\rm{xx}}}/{\theta }_{{SH}}^{2}\) for these samples in comparison to Pt, Ta, W, our previous ion-implantation samples, Pt(S), Pt(O), and Pt(N), and even PdPt, IrAl and OsAl alloys. Performing current driven perpendicular magnetization switching of ferrimagnetic GdFeCo, using both pure Pt and Pt(P) as SOT sources, \({J}_{{\rm{sw}}}\) is found to decrease for Pt(P). This decrease is attributed to the increase in \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\). Expressing the magnetization switching efficiency in terms of the switching energy density, \({U}_{{\rm{sw}}}\) for Pt(P) exhibits 4 times smaller as compared to pure Pt. Our findings of a giant SHE in Pt(P) also provide an alternative pathway to enhance \({\theta }_{{\rm{SH}}}\) by using amorphous materials with a variety of elements, leading to a higher \({\sigma }_{{\rm{xy}}}^{{\rm{SH}}}\), a PMA friendly material for reduced \({J}_{{\rm{sw}}}\), and lower power consumption for SOT driven memory and logic devices.

Materials and methods

Material preparation and characterization

Multilayer stacks of Pt (5–10 nm)/MgO (10 nm)/Al2O3(10 nm) was deposited on Si/SiO2 substrates at room temperature using an ultra high vacuum magnetron sputtering. The Pt layer was deposited at a DC power of 50 W and Ar gas pressure of 1 Pa. Then the sample was transferred to an oxide deposition chamber for preparing MgO and Al2O3 capping layers under partial pressure of Ar and O2 gas. The deposited Pt/MgO/Al2O3 stacks were implanted with 10–30 keV-P ion-beam using ULVAC IMX-3500. The XRD and XRR data were collected using Rigaku SmartLab. Cross-sectional TEM samples were prepared by mechanical polishing, followed by Ar-ion thinning technique. The observations of HAADF-STEM images as well as electron diffraction patterns were carried out with JEM-3000F (acceleration voltage: 300 kV) and JEM-F200 (acceleration voltage: 200 kV) microscopes at room temperature. The electronic structure and local crystallographic structure of pure and implanted Pt films were studied by XAS measurements carried out at National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center, Taiwan. The XAS spectra at Pt L3 edge was recorded using beamline TPS 44A1 in total electron yield mode, aligning the film surface normal to the incident beam.

SOT-driven magnetization switching measurements

For the samples used for SOT-driven switching measurements, the capping layers of MgO and Al2O3 were removed from the Pt(P)/MgO/Al2O3 stacks by Ar+ ion milling and monitored using end point detector monitor. Following this, Gd25(Fe75Co25)75 (10 nm) amorphous layers were deposited by co-sputtering FeCo and Gd targets at room temperature. A SiN (10 nm) capping layer was used to prevent oxidation of GdFeCo. The deposited stacks were patterned into Hall crosses of different dimensions by ultraviolet photolithography and Ar+ ion milling. Ti(10 nm)/Al(200 nm) electrodes were sputtered onto the samples to perform electrical measurements. The results in this work correspond to measurements performed on Hall crosses having both current channel width and Hall voltage channel width of 30 μm.

ST-FMR measurements

For the ST-FMR measurements, firstly, the remaining protective layers of MgO/Al2O3 were removed from Pt(P)/MgO/Al2O3 by Ar+ ion milling and monitored using end point detector monitor. Secondly, NiFe (5 nm) was deposited on top of these samples by using an ultrahigh vacuum sputtering. Thirdly, the Pt(P)/NiFe bilayers were patterned into microstrips using standard photolithography techniques. Finally, coplanar waveguides (CPW) electrodes with a Ground-Source-Ground (G-S-G) of Ti (10 nm) and Al (200 nm) were formed by DC sputtering with 50 W and 100 W, respectively.

References

Hirsch, J. E. Spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 1834–1837 (1999

Sinova, J., Valenzuela, S. O., Wunderlich, J., Back, C. H. & Jungwirth, T. Spin Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 1213–1260 (2015

Bychkov, Y. A. & Rashba, E. I. Properties of a 2D electron gas with lifted spectral degeneracy. JETP Lett. 39, 78–81 (1984

Edelstein, V. M. Spin polarization of conduction electrons induced by electric current in two-dimensional asymmetric electron systems. Solid State Commun. 73, 233–235 (1990

Shao, Q. et al. Roadmap of spin-orbit torques. IEEE Trans. Magn. 57, 1–39 (2021

Liu, L. et al. Spin-Torque Switching with the Giant Spin Hall Effect of Tantalum. Science 336, 555–558 (2012

Liu, L., Moriyama, T., Ralph, D. C. & Burhman, R. A. Spin-Torque Ferromagnetic Resonance Induced by the Spin Hall Effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 036601 (2011

Manchon, A. et al. Current-induced spin-orbit torques in ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 035004 (2019

Wang, P. et al. Giant spin Hall effect and spin–orbit torques in 5d transition metal–aluminum alloys from extrinsic scattering. Adv. Mater. 34, 2109406 (2022

Fujiwara, K. et al. 5d iridium oxide as a material for spin-current detection. Nat. Commun. 4, 2893 (2013

Han, J. et al. Room-Temperature Spin-Orbit Torque Switching Induced by a Topological Insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 077702 (2017

Jeong, J. et al. Reduced Spin-Orbit Torque Switching Current by Voltage-Controlled Easy-Cone States. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2107944 (2022

Zhu, L. Switching of Perpendicular Magnetization by Spin–Orbit Torque. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300853 (2023

Shashank, U. et al. Enhanced Spin Hall Effect in S-Implanted Pt. Adv. Quantum Technol. 4, 2000112 (2021

Shashank, U. et al. Highly dose dependent damping-like spin–orbit torque efficiency in O-implanted Pt. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 252406 (2021

Shashank, U. et al. Disentanglement of intrinsic and extrinsic side-jump scattering induced spin Hall effect in N-implanted Pt. Phys. Rev. B 107, 064402 (2023

Was, G. S. Fundamentals of Radiation Materials Science; Metals and Alloys. (Springer, New York, 2017).

Yu, J. et al. Long spin coherence length and bulk-like spin–orbit torque in ferrimagnetic multilayers. Nat. Mat. 18, 29–34 (2019

Mathew, A. J. et al. Realization of logic operations via spin–orbit torque driven perpendicular magnetization switching in a heavy metal/ferrimagnet bilayer. J. Appl. Phys. 135, 213902 (2024

Zhao, X. et al. Asymmetric current-driven switching of synthetic antiferromagnets with Pt insert layers. Nanoscale 10, 7612–7618 (2018

Torrejon, J. et al. Current-driven asymmetric magnetization switching in perpendicularly magnetized CoFeB/MgO heterostructures. Physical Review B 91, 214434 (2015

Shashank, U. et al. Room-Temperature Charge-to-Spin Conversion from Quasi-2D Electron Gas at SrTiO3-Based Interfaces. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 17, 2200377 (2022

Shashank, U. et al. Charge-spin interconversion in nitrogen sputtered Pt via extrinsic spin Hall effect. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 36, 235802 (2024

Vashisht, G. et al. Pinning-assisted out plane anisotropy in reverse stack FeCo/FePt intermetallic bilayers for controlled switching in spintronics. J. Alloys. Compd. 877, 160249 (2021

Harder, M., Gui, Y. & Hu, C.-M. Electrical detection of magnetization dynamics via spin rectification effects. Phys. Rep. 661, 1–59 (2016

Kumar, A. et al. Interfacial origin of unconventional spin-orbit torque in Py/IrMn3. Adv. Quantum Technol. 6, 2300092 (2023

T. Skinner, Electrical control of spin dynamics in spin-orbit coupled ferromagnets, Doctoral Dissertation, University of Cambridge, (2014).

Sklenar, J. et al. Unidirectional spin-torque driven magnetization dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 95, 224431 (2017

Okada, A. et al. Spin-pumping-free determination of spin-orbit torque efficiency from spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 014040 (2019

MacNeill, D. et al. Control of spin–orbit torques through crystal symmetry in WTe2/ferromagnet bilayers. Nat. Phys. 13, 300–305 (2017

Pai, C.-F., Ou, Y., Vilela-Leão, L. H., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Dependence of the efficiency of spin Hall torque on the transparency of Pt/ferromagnetic layer interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 92, 064426 (2015

Agarwala, A. & Shenoy, V. B. Topological Insulators in Amorphous Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 236402 (2017

Mitchell, N. P., Nash, L. M., Hexner, D., Turner, A. M. & Irvine, W. T. M. Amorphous topological insulators constructed from random point sets. Nat. Phys. 14, 380–385 (2018

Fujiwara, K. et al. Berry curvature contributions of kagome-lattice fragments in amorphous Fe–Sn thin films. Nat. Commun. 14, 3399 (2023

Kondou, K. et al. Fermi-level-dependent charge-to-spin current conversion by Dirac surface states of topological insulators. Nat. Phys. 12, 1027–1031 (2016

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by JSPS Grant-in-Aid (KAKENHI No. 22K04198), Iketani Science and Technology Foundation, Tanaka Kikinzoku Memorial Foundation, Heiwa Nakajima Foundation and Meisenkai. We thank Dr Rohit Medwal and Dr Asokan Kandasami for discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

U. S. and Y. F. designed the experiments. U. S., T. T., A. J. M, G. V., K. I., Y. K, and H. A. fabricated devices and collected the data. H. A. deposited GdFeCo films. C. –L. D. and C. –L. C. performed XAS measurements. Y. H. and M. I. performed XRD, XRR and STEM measurements. U. S., A. J. M and G. V. wrote the manuscript with input from Y. H., M. I., H. A., and Y. F. Y. F. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shashank, U., Tomoda, T., Mathew, A.J. et al. Giant spin-orbit torque induced by spin Hall effect in amorphous Pt(P) alloys. NPG Asia Mater 17, 15 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00596-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00596-6