Abstract

Replacing Ir with anode catalyst materials that are more abundant is a long-sought objective within the CO2 electrolysis community. The chemical environment (near-neutral pH, carbonate buffer electrolyte) that inherently develops during long-term operation, however, limits the pool of applicable candidates. In this contribution, Ir was replaced with a porous Co3O4 nanosheet catalyst layer as the anode of a zero-gap CO2 electrolyzer cell. The catalyst was directly deposited on the Ti porous transport layer via hydrothermal synthesis, which allowed the precise control of the catalyst loading. Under optimal conditions (7 mg cm-2 Co3O4 loading), 300 mA cm-2 current density was reached at 3.4 V applied cell voltage. The electrolyzer cell with the Co3O4 anode was operated continuously for 50 hours at 250 mA cm-2 current density with stable cell voltage and CO2 reduction selectivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Iridium is the most frequently employed anode catalyst in CO2 electrolysis1. However, due to mainly economic reasons, and its instability under certain CO and CO2 reduction conditions2, its replacement with more abundant and stable catalysts has been a long-sought objective of the electrolysis community. While it seems to be a straightforward task at first glance, several peculiarities of CO2 electrolysis must be considered, to find the right anode catalyst material. The anode and cathode compartments are typically separated by an anion exchange membrane (AEM), and in these cases, carbonate ions are the main species maintaining ion conduction (especially at high current densities)3. This means that during the operation of the electrolyzer cell, a high carbonate flux crosses over the membrane from the cathode to the anode side and directly hits the anode catalyst layer. If the anolyte is recirculated (which must be the case in any practical application), the continuous transport of carbonate ions gradually decreases the anolyte pH until a near-neutral value is reached (a carbonate/bicarbonate buffer solution forms)3. This is a key difference compared to AEM water electrolyzers, where the OH- ions crossing over the AEM are immediately neutralized by the H+ ions formed at the surface of the anode catalyst during water oxidation (OER)4. This is the reason why materials such as Ni, which shows high activity and stability in alkaline media, can only be used in CO2 electrolysis if the anolyte pH is continuously monitored and adjusted by the addition of concentrated alkaline electrolyte to preserve its alkaline character3.

Based on the above considerations, first and foremost, the ideal catalyst candidate should show high OER activity in near-neutral pH electrolytes containing carbonate/bicarbonate ions in high concentrations. Secondly, it should be composed of cheap and abundant materials (that are ideally not declared as critical raw materials) (https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/raw-materials/areas-specific-interest/critical-raw-materials_en), and that can be synthesized by a method that is readily scalable to meet the needs of large-scale electrolyzer cells. Precedent reports on near-neutral OER were carried out mostly either in borate or phosphate buffer solutions5. In contrast, only a handful of research employed carbonate buffer solutions1,6,7. Catalysts in these studies are mostly based on Cu, Fe, Ni, Co, or even Ir, and their common feature is that the active form develops during the OER6,7,8,9,10,11. The formation of transition metal carbonates can stabilize metals that are otherwise unstable at the near-neutral pH environment3, such as Ni12. Such a catalyst-electrolyte interaction was observed first in the case of Co in a neutral pH electrolyte solution containing phosphate ions13.

Research on Co-based oxides dates back to the 1980s’14. Since then, Co-based oxides gained most notable attention due to their high OER activity and durability in alkaline media15,16. The durability of Co3O4 in alkaline electrolytes lies in its low dissolution rates. However, a reversible structural and morphological alteration of the catalyst surface has been observed under OER conditions17. More closely, an amorphous CoOx(OH)y layer with di-μ-oxo-bridged Co4+/3+ ions forms on top of Co3O4. The development of these sites is an essential condition for Co3O4 to drive the OER17. The demonstration of the stability of Co3O4 in neutral phosphate anion-containing electrolytes13, was followed by the application of Co3O4 in near-neutral and even acidic electrolytes18,19,20,21. Furthermore, Co3O4 has already been tested as an anode catalyst in pure water electrolysis22,23 and in neutral pH seawater electrolysis24. In the former examples, the short-term (20 h) OER performance of Co3O4 matched closely with the values obtained for IrO2 at j = 500 mA cm-2 applied current density. It was demonstrated that OER activity can be maintained even for 250 hours at the same current density, keeping the degradation rate below 1 mV h-1. Similarly to IrO2, the reason behind the observed degradation is mainly due to ionomer oxidation coupled with the change in surface composition/morphology. One of the main issues with Co3O4 is that it is intrinsically a semiconductor, which in turn results in higher cell voltage.

Co3O4 has a spinel structure15, in which it is relatively easy to incorporate other cations (di-, and trivalent), which opens the possibility to tailor its intrinsic properties. There are many examples in the literature where the bare Co3O4 structure was doped with Pd, Cr, Fe, Ni, etc15,24,25. Besides cations, Co3O4 can be modified by other elements (e.g., F and N) too26,27. The purpose of the various dopants is to tailor the electronic structure of the catalyst, leading to improved charge transfer and, hence, higher OER activity and increased durability in acidic electrolytes (corrosion resistance of bare Co3O4 at acidic pH is moderate). The resulting modified Co3O4 anodes were successfully applied in polymer electrolyte membrane water electrolyzers, achieving high current densities (over 1 A cm-2) at low overpotentials in acidic electrolytes approaching the performance of state-of-the-art noble metal systems (e.g., RuO2)25,26.

In contrast to water electrolysis28, to our knowledge, no information is available on how Co3O4 behaves in the environment that develops during long-term CO2 electrolysis with recirculated electrolyte (near-neutral pH carbonate buffer). According to thermodynamics, bare Co oxides are only stable at relatively high overpotentials in such an environment, in the potential regime where OER typically proceeds12. However, these statements have not been verified under CO2 electrolysis conditions where kinetic effects could alter predictions from thermodynamics.

In this study, Ir was replaced with porous Co3O4 as the OER catalyst in a CO2 electrolyzer cell. Co3O4 was prepared via a hydrothermal method allowing the direct deposition of the catalyst on the Ti porous transport layer (PTL). This approach resulted in direct contact between the catalyst and the PTL, which is critically important in achieving high-performance CO2 electrolysis. The synthesis method is scalable; it is only limited by the size of the substrate and the autoclave. The electrochemical performance was probed in a zero-gap electrolyzer cell as a function of the thickness of the catalyst layer. The experienced stable long-term activity and CO2RR selectivity highlight the possible use of this alternative anode catalyst to replace scarce and expensive catalysts in CO2 electrolyzer cells.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2 · 6H2O, ≥98%, Sigma-Aldrich), urea (CO(NH2)2, 99.0-100.5%, Sigma-Aldrich), ammonium fluoride (NH4F, ≥99.99%, Sigma-Aldrich), cesium hydroxide (Sigma-Aldrich), isopropanol (IPA, WVR), Ag nanoparticles (d < 100 nm, Sigma-Aldrich), Ir black (d = 4-6 nm, FuelCellStore), and commercial Co3O4 nanoparticles (NPs) (US Research Nanomaterials Inc., d = 30-50 nm) were purchased in analytical grade and used without further purification. The Nafion ionomer dispersion (10 wt%), Ti porous transport layer (PTL, 250 µm thickness) and the Freudenberg H23C6 carbon-based gas diffusion layer (GDL)was acquired from FuelCellStore. The PiperION anion exchange membrane (40 µm thickness), along with the PiperION ionomer (A5-HCO3-EtOH) used in the cathode catalyst layer, was purchased from Versogen. All solutions were prepared using MilliQ grade (Millipore Direct Q3-UV, 18.2 MΩ cm) ultrapure water. A 4.5 purity CO2, and 4.7 purity Ar were used to perform the electrolysis measurements. Both gases were purchased from Messer.

Preparation of the anode and cathode catalyst layers

Prior to synthesis, Ti PTLs were cleaned by using a detergent and a brush under water flow. Afterward, all PTLs were sonicated in ultrapure water until no foaming was observed on top of the water layer. The PTLs were dried under air.

The synthesis of Co3O4 on the cleaned Ti PTLs was adapted from the work of Chen et al. 29, Scheme S1. First, varied amounts (3 mmol for the loading of ca. 13.0 ± 0.3 mg cm-2 of Co3O4 on Ti) of Co(NO3)2 · 6H2O were dissolved in 35 cm3 (for the higher loadings) or 17.5 cm3 (for the lower loadings) of H2O. Then, 8 mmol of NH4F and 14 mmol of CO(NH2)2 were added to the solution and stirred until complete dissolution. Afterwards, the Ti PTL was placed at the bottom of the 100 cm3 Teflon-lined autoclave, where subsequently the prepared solution was added. It was then heated up to 120 °C for 12 hours. After cooling to room temperature, the Ti PTL covered with the Co precursor was removed from the autoclave, cleaned with water, dried, and transferred to the crucible for calcination at 400 °C for 1 hour in air atmosphere in a muffle furnace. The heating rate was set to 1 °C min-1 to avoid rapid heating and thus destruction of the formed oxide layers. The final loading of Co3O4 on the Ti PTLs was obtained gravimetrically.

Control measurements were performed using Ir black as the anode catalyst. 150 mg catalyst was dispersed in 1:1 ultrapure water:IPA (7.5 cm3 total volume). 15 wt% PiperION was added to the catalyst dispersion, which was homogenized for 20 min in an ultrasonic bath. The dispersion was spray-coated on the Ti PTL using an airbrush and compressed air. The catalyst loading was maintained at 1 mg cm-2 with respect to the metal content. As for the cathode catalyst ink, 196 mg Ag NPs were dispersed in 1:1 ultrapure water:IPA (8 cm3 total volume). Prior to adding the ionomer (PiperION, 0.3 wt%) the dispersion was homogenized with an immersion sonotrode (Hielscher UP200ST). After adding the ionomer, the dispersion was sonicated further for 20 min in an ultrasonic bath. The dispersion was spray-coated on a Freudenberg H23C6 GDL until reaching 1 mg cm-2 metal loading.

Structural and morphological characterization

Crystal structure of the pristine and the used Co3O4 layers was determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Rigaku MiniFlex II instrument equipped with a Cu Kα (λ = 1.5418 Å) X-ray source. Operating conditions were 30 kV, 15 mA in the 5°–80° 2Θ range, with a scan speed of 1.0° min–1.

The composition and morphology of the anode catalyst layer were scrutinized with scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Thermo Scientific Apreo 2) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray detector.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Al Kα hν = 1486.6 eV) was used to reveal the surface composition of the anode catalyst layers. XPS was employed with a SPECS instrument equipped with a PHOIBOS 150 MCD 9 hemispherical analyzer. It was used in a fixed analyzer transmission mode with 40 eV pass energy for the survey scans and 20 eV pass energy for the high-resolution scans. Charge referencing was done to the adventitious carbon (284.8 eV) on the surface of the sample. Spectra were evaluated using the CasaXPS software package.

Electrolysis experiments

All electrochemical results presented in this study were performed in a custom-designed zero-gap electrolyzer cell (A = 8 cm2). Details on the structure of the cell and further information are available in our precedent publications3,30,31. The Co3O4-modified Ti PTLs were employed as the anode of the cell, while the Ag NPs-coated Freudenberg H23C6 GDE was used as the cathode in all cases. The anode and cathode compartments were separated with a 40 µm thick PiperION AEM, which was activated and stored in 1.0 M CsOH at least 24 h prior to use. Humidified CO2 or Ar (in the case of the water electrolysis control experiments) was fed to the cathode with a flow rate of 100 cm3 min-1, while a 0.05 M CsOH solution was used as the anolyte, which was saturated with CO2 prior to the electrolysis measurements (to yield CsHCO3) and pumped to the anode compartment of the cell with a flow rate of ca. 70 cm3 min-1. 100 cm3 electrolyte was recirculated over the course of the measurements. The gas flow rate was controlled by a Bronkhorst MASS-STREAM D-6321 type mass flow controller. The cell temperature was maintained at 60 °C throughout the measurements.

All electrochemical measurements were performed using a BioLogic VMP-300 potentiostat/galvanostat equipped with an impedance module and a 5 A/10 V booster. The reported current density values correspond to normalizing the current measured by the geometric active area of the cell. The electrochemical protocol consisted of recording three linear sweep voltammograms (LSVs) in the potential range of 0.8 V and 3.2 V (Ir black anode) or 3.4 V (Co3O4 anode). This was followed by 30-minute-long potentiostatic experiments at different fixed cell voltages of 2.8 – 3.4 V, ΔU = 0.2 V. The protocol was finished by recording an electrochemical impedance spectrum at the cell voltage value that was applied in the given potentiostatic experiment. The formed CO2RR products were quantified with either a Shimadzu Nexis-GC-2030 gas chromatograph, equipped with a barrier discharge ionization detector or with an online infrared-thermal conductivity gas analyzer (Gasboard-3100, customized for CO2-CO-H2 mixtures, Hubei Cubic-Ruiyi). The latter allowed the quantification of gas phase products in real-time. Long-term measurements were performed using the same test framework described above. For evaluating the long-term stability of the catalyst layer, a galvanostatic protocol was used by applying 250 mA cm-2 current density. The current density was ramped up in two steps to this value by applying 100 mA cm-2 and 200 mA cm-2 current density, each for an hour, prior to reaching the 250 mA cm-2 value.

Ex-situ ICP-MS measurements

The electrolytes collected after the cell operation were analyzed by inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, PerkinElmer NexION 350X). ICP-MS was calibrated prior to each set of measurements by a four-point calibration slope (0, 0.5, 1.0, and 5.0 μg L-1) prepared from standard solutions that contained 59Co and 48Ti in each concentration. 74Ge and 45Sc were used as an internal standards for Co and Ti, respectively. The internal standard solution was prepared in 1% HNO3 electrolyte and was introduced to the nebulizer of the ICP-MS via a Y-connector. All the analyzed electrolytes were diluted 100 times, and this dilution factor was considered when calculating the concentrations of the dissolved species.

Results and Discussion

We employed a straightforward two-step synthesis route adapted from the literature29 to grow the cobalt oxide layers on the Ti mesh. Scheme S1 demonstrates the concept and the synthesis steps, which include (1) mixing the cobalt nitrate as a precursor and two surfactants (or growth-directing agents)32,33: urea and ammonium fluoride (NH4F), in water; (2) performing a hydrothermal step overnight; and (3) calcining the obtained materials at 400 °C on air. By changing the concentration of the precursor, we managed to vary the final loading of Co3O4 on the Ti PTL from ca. 2.5 mg cm-2 to ca. 13.3 mg cm-2.

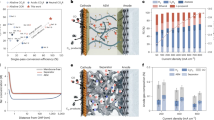

The morphology of the synthesized Co3O4 electrodes was studied with SEM. As shown in Fig. 1A, Co3O4 was deposited with a porous morphology, and coated the surface of the Ti PTL evenly. Co3O4 appears as relatively large (several μm in diameter) 2D flakes (Fig. S1), in line with the precedent literature29. The homogeneous coating was further confirmed by SEM-EDX maps (Fig. S1 and Table S1). The amount of Co in the sample was 47.9 ± 1.99 at% while the O content was 51.2 ± 2.01at%. The small Ti signal originates from the underlying porous Ti PTL.

A SEM image recorded for the synthesized Co3O4 sample. B XRD patterns collected for the as-synthesized Co3O4 sample, a Co3O4 sample after performing the electrochemical protocol described in the experimental, and for a Co3O4 sample acquired from a commercial source. C, D High-resolution XPS spectra recorded for the Co3O4 sample. The catalyst loading on the Ti PTL was ≈ 7 mg cm-2.

The crystal structure and composition of the as-synthesized samples were scrutinized by XRD (Fig. 1B). A total of seven diffraction peaks ((111), (220), (311), (222), (400), (511), (440)) can be identified on the diffractogram recorded for the Co3O4 electrode, that match well with the ones detected for the commercial sample and with previous reports in the literature34,35,36. According to these, the synthesized Co3O4 bears a face-centered-cubic crystal structure typical for spinels. XRD data was processed further by performing Rietveld refinement (Figs. S2, Fd-3m point group Co3O4, a = 8.05671 Å). Based on the analysis, the average crystal domain size is 19 nm, which is identical to the value determined from the Scherrer equation.

The surface composition of Co3O4 was analyzed with XPS, where Co, O, and C could only be identified on the survey scans (Figure S3). The adventitious carbon on the sample surface was used for charge referencing (Figure S4). High-resolution scans of the Co 2p3/2 region (Fig. 1C) suggest that Co3O4 is the dominant phase in the case of all samples37. Two cobalt chemical environments were considered (octahedrally (Peak 1) and tetrahedrally (Peak 2) coordinated) with their respective satellite features hallmark of spinel structured Co3O4. The core-level O1s spectrum (Fig. 1D) was fitted with three peaks corresponding to lattice oxide (33 at%) to surface carbonate/hydroxide (63 at%), and a small amount of adsorbed water (3 at%) at the surface of the sample. The exact components and binding energies used for the fittings are summarized in Table S2.

Figure 2A shows linear sweep voltammograms (LSVs) recorded using either Ir black or Co3O4 as the anode catalyst, under identical experimental conditions. In the case of Ir, the current density monotonously increased to reach 600 mA cm-2, after the onset (a cell voltage of 1.85 V is required for Ir to reach 10 mA cm-2 current density). Contrastingly, the highest current density that was measured for the Co3O4 sample (≈7 mg cm-2 loading) was 225 mA cm-2 at 3.20 V cell voltage, which is a notable difference between the two systems (in the case of Ir, 100 mA cm-2 current density was reached at Ucell = 2.40 V, while the cell required Ucell = 2.88 V to achieve the same value for Co3O4). The other difference is that in the case of the Co3O4 sample, two small peaks appeared at 1.27 V and 1.67 V cell voltage. The first corresponds to the transformation of Co3O4 to CoOOH (Co2+ to Co3+), while the second appeared due to the further oxidation of the Co3+ to Co4+ sites (CoO2 formation)34,38. These intermediates play a key role in driving the OER, hence, it starts only after the oxidation of the catalyst surface38. The onset of OER is approximately 300 mV more positive compared to what was observed for Ir.

A LSVs recorded for the zero-gap cell employing either Ir or Co3O4 as the anode catalyst in 60°C, 0.05 M CsOH electrolyte saturated with CO2. The sweep rate was 100 mV s-1. Electrolyte and CO2 flow rates were maintained at 70 cm3 min-1 and 100 cm3 min-1, respectively. The anode catalyst loading was 1 mg cm-2 and 7 mg cm-2 for the Ir and Co3O4 catalysts, respectively. B Chronoamperometry measurements performed at different fixed cell voltages in the range of 2.8 V and 3.4 V for 30 min. Conditions were identical as in the case of (A). C CO2RR selectivity monitored during the chronoamperometry measurements. Selectivity was determined after the measured current reached a stable value.

The potentiodynamic experiments were immediately followed by chronoamperometry measurements at different cell voltages (Fig. 2B). In the case of the Co3O4 sample, 65 mA cm-2 current density was measured at 2.80 V cell voltage. The current rapidly increased with the applied cell voltage reaching almost 315 mA cm-2 at 3.40 V. After setting the given cell voltage, the current stabilizes (in the first five minutes) and remains constant throughout the measurement. Contrastingly, around 350 mA cm-2 total current was measured at the lowest cell voltage (Ucell = 2.80 V) when the Ir black catalyst was the anode, which rose up to almost 450 mA cm-2 at 3.20 V. Stabilization of the measured current took notably longer compared to the Co3O4-case. CO2RR selectivity is similar regardless of the anode catalyst (Fig. 2C); 85–92% of the passed charge was consumed by CO formation.

After the first CO2 electrolysis measurements, a control experiment was performed using the same anode (Co3O4 and Ir black) and cathode (Ag NPs) catalysts but running water electrolysis instead. The electrolyte was saturated with CO2 prior to the measurements, but CO2 was switched to Ar at the start of the electrolysis (Fig. S5). Galvanostatic experiments were performed to facilitate comparison with Ir (i.e., at identical reaction rates). In the case of Co3O4, the cell voltage gradually increases with the current density (around 3.05 V at 300 mA cm-2). These values are considerably higher than what is expected from a water electrolyzer cell running with pure water as the electrolyte22, but the cell voltage remained stable throughout the experiments. When the same measurement was performed with Ir black as the anode, the cell voltage was notably lower (as expected from the previous CO2RR experiments), around 2.57 V at 300 mA cm-2 applied current density. Cell voltage remained stable at all three current density values. These values are also higher than the ones typically measured for IrO2 in water electrolyzer cells (e.g., around 2 V in pure water at 500 mA cm-2 current density22), most likely because Ag was applied as a HER catalyst and because of the near-neutral pH carbonate buffer electrolyte.

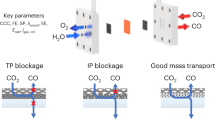

The Co3O4 catalyst loading was varied between 2.45 and 13.26 mg cm-2. The achievable current density is visibly affected by the thickness of the catalyst layer (Fig. 3A). The thinner Co3O4 layers yield higher current densities than their thicker counterparts, indirectly suggesting that the conductivity of the catalyst layer could be one of the key factors limiting the apparent activity. Besides conductivity, the lower measured current density could be the result of mass-transport limitations developed due to the considerably thicker catalyst layer (especially an issue with higher loadings of 10.7 and 13.26 mg cm-2). The highest current densities at all applied cell voltages were found for the anode catalyst layer with 7.0 mg cm-2 loading (for specific values cf. Figure 3B). The measured current density rapidly decreases when the catalyst loading exceeds the optimum value. Figure 3C depicts the CO2RR selectivity data for all the tested Co3O4 loadings at 3.40 V applied cell voltage. The CO2:H2 ratio is unaffected by the loading of the anode catalyst regardless of the applied cell voltage (see Fig. S6-S10).

A Chronoamperometry measurements performed at Ucell = 3.40 V varying the loading of the Co3O4 anode catalyst in 60°C, 0.05 M CsOH electrolyte saturated with CO2. Anolyte and CO2 flow rates were maintained at 70 and 100 cm3 min-1, respectively. B CO2RR selectivity monitored during the chronoamperometry measurements. Selectivity was determined after the measured current reached a stable value. Error bars were calculated from at least two separate measurements, using fresh MEA each time.

To characterize the performance loss experienced for the thicker catalyst layers further, an impedance spectrum was recorded at each applied cell voltage. This was followed by the extraction of the Rs values (Fig. 4A), which are more or less constant until reaching the 7 mg cm-2 catalyst loading, but then rapidly increase with the amount of the catalyst deposited on the Ti PTL. The Rs values determined for the Co3O4 samples with low-loading (until 7 mg cm-2) are similar to the values typically experienced when Ir black is used as the anode catalyst.

A Series resistance values extracted from potentiostatic impedance spectra recorded applying 3.4 V cell voltage and varying the loading of the anode catalyst. Measurements were performed in 60°C, 0.05 M CsOH electrolyte saturated with CO2 applying 70 cm3 min-1 anolyte, and 100 cm3 min-1 CO2 flow rate. The blue-shaded area represents a range of Rs values typically determined when Ir is used as the anode catalyst. B Dissolved amount of Co determined with ICP-MS from the electrolyte after performing the electrochemical protocol described in the experimental section.

The amount of Co3O4 dissolved/detached during electrolysis was quantified by ex-situ ICP-MS measurements (Fig. 4B). The as-prepared Co3O4 catalyst layers were rather porous, which might lead to the detachment of at least part of the catalyst layer due to the moderate electrolyte flow rate. ICP-MS data can provide information only on the amount of Co dissolved during electrolysis; it is not able to directly quantify the amount of potentially detached Co3O4 nanoparticles. At low Co3O4 loadings, the Co loss due to dissolution is around 0.1 μg cm-2 (e.g., it is around 2·10-3 w% in the case of the sample with 4.85 mg cm-2 loading), while this value increases above 0.158 µg cm-2 when the oxide loading reaches 7 mg cm-2. All in all, the amount of dissolved Co seemingly does not change notably by the increasing catalyst loading. Based on these dissolved Co amounts, it can be concluded that the synthesized Co3O4 nanosheet anode catalysts are reasonably stable under conditions that develop in zero-gap CO2 electrolyzer cells (carbonate electrolyte and high carbonate flux through the AEM, near-neutral pH).

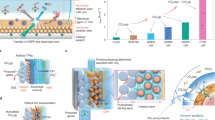

To assess the long-term stability of the CO2 electrolyzer cell equipped with the Co3O4 anode catalyst layer, long-term chronopotentiometry experiments were conducted using an in-house developed automated test station39. First, tests were performed employing the anodes with 7 mg cm-2 catalyst loading, applying 300 mA cm-2 constant current density (Figure S11). The cell voltage and the CO2RR selectivity remained stable for the first 20 hours of the 50 hours of constant operation, and then the CO selectivity decreased gradually. This was followed by the disassembly of the electrolyzer cell and the MEA. A series of small pinholes were observed in the membrane that probably formed upon cell assembly and increased in size slowly during operation. It might be that the morphology of the Co3O4 nanosheets (sharp edges) caused this issue (see images captured at higher magnification in Fig. S1). To test this hypothesis, an anode Co3O4 layer with 4.85 mg cm-2 catalyst loading was used (i.e., an anode having a less rough surface). The applied final current density was also decreased to 250 mA cm-2, and it was ramped up in a series of 100, 200 mA cm-2, each one was held for an hour prior to reaching the final value (Fig. 5). Cell voltage was stable over the course of the measurement revolving around 3.40–3.50 V. CO2RR selectivity remained constant for 50 hours with around 90% FE towards CO formation. The anolyte pH was monitored throughout the measurement. The measured pH values were scattered in between 7.05 and 7.30 meaning that the electrolyte preserved its near-neutral character over the course of the experiment under which Co3O4 is stable.

Long-term chronopotentiometry measurement was performed by applying jtotal = 250 mA cm-2 current using a Co3O4 anode catalyst with a loading of 4.85 mg cm-2. Data was collected in 60°C, 0.05 M CsOH electrolyte saturated with CO2. Electrolyte and CO2 flow rate was maintained at 70 and 100 cm3 min-1, respectively. CO2RR selectivity data is presented at the bottom.

After the successful long-term experiment, the cell was disassembled, and the MEA components were scrutinized. Figure S12 shows the SEM images recorded after the measurement. The original plate-like structures transformed to needle-like features on the top of the catalyst layer. EDX analysis (Table S1) shows a decrease in the amount of Co, along with an increase in the O-content and in the recorded Ti signal. The latter suggests that at least part of the catalyst layer either detached from the surface to the electrolyte or stuck to the AEM upon disassembly, decreasing the catalyst layer thickness, which can be penetrated by the electrons reaching even the underlying Ti paper PTL. High-resolution Co 2p3/2 XPS spectra (Figure S13) suggest the formation of CoOOH phase besides Co3O4, which is in line with the experienced morphology change. The O1s peak shifted towards lower binding energies after the measurement, implying also the formation of the oxohydroxide phase (lattice oxide is around 45 at%, while the surface hydroxide is around 55 at%). Contrastingly, XRD of the as-synthesized Co3O4 (Fig. 1C) and the one after the long-term experiment are identical, indirectly indicating that the previously described alterations appeared only at the catalyst surfac,e leaving the bulk unchanged. No Co was detected within or on the cathode side of the AEM by looking at the EDX mapping data (Figure S14). The membrane remained intact throughout the measurement; using the lower Co3O4 loading, no holes can be observed by the naked eye in the membrane.

Conclusions

In this proof-of-concept study, Ir was replaced by porous Co3O4 nanosheets and employed as an anode catalyst in a CO2 electrolyzer cell. To alleviate conductivity issues intrinsically originating from the semiconducting nature of Co3O4 and from the inadequate connection between the PTL and the catalyst particles, Co3O4 was directly synthesized on the surface of the Ti paper PTL by a simple hydrothermal method. This approach allowed the precise tailoring of the catalyst loading. 7 mg cm-2 catalyst loading was found to be optimal, the measured current densities reached around 300 mA cm-2 at 3.4 V applied cell voltage. Additionally, only a marginal amount of Co leached to the electrolyte during the several hours-long electrochemical protocol. The CO2 electrolyzer with Co3O4 as the anode catalyst was operated galvanostatically continuously for over 50 hours, applying 250 mA cm-2 current density. CO2RR selectivity and Ucell remained stable throughout the measurement. Our results indicate that Co3O4 can withstand the conditions developing during long-term CO2 electrolysis (near-neutral pH, carbonate-containing electrolyte). The presented results could be further improved by optimizing the initial morphology of Co3O4 or by introducing other metals in the spinel crystal structure (therefore improving the conductivity of the oxide requiring the deposition of less material on the Ti PTL). Overall, we demonstrated that it is possible to replace Ir with more abundant, non-noble, and, hence, financially more favorable alternatives. The presented synthesis method is readily scalable; only the size of the hydrothermal reactor is the limit. These together can support the penetration of CO2 electrolysis technology at an industrial level.

References

Vass, A., Kormányos, A., Kószó, Z., Endrődi, B. & Janáky, C. Anode catalysts in CO2 electrolysis: challenges and untapped opportunities. ACS Catal. 12, 1037–1051 (2022).

Xu, Q. et al. Identifying and alleviating the durability challenges in membrane-electrode-assembly devices for high-rate CO electrolysis. Nat. Catal. 6, 1042–1051 (2023).

Vass, et al. Local chemical environment governs anode processes in CO2 electrolyzers. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 3801–3808 (2021).

Li, Q. et al. Anion exchange membrane water electrolysis: the future of green hydrogen. J. Phys. Chem. C. 127, 7901–7912 (2023).

Dong, Y., Oloman, C.W., Gyenge, E.L., Su, J. & Chen, L. Transition metal based heterogeneous electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction at near-neutral pH. Nanoscale 12, 9924–9934 (2020).

Jiang, N., Zhu, Z., Xue, W., Xia, B.Y. & You, B. Emerging electrocatalysts for water oxidation under near-neutral CO2 reduction conditions. Adv. Mater. 34, 1–22 (2022).

Joya, K.S., Takanabe, K. & de Groot, H.J.M. Surface generation of a Cobalt-derived water oxidation electrocatalyst developed in a neutral HCO3−/CO2 System. Adv. Energy Mater. 4, 2–7 (2014).

Meng, Y. et al. Highly active oxygen evolution integrated with efficient CO2 to CO electroreduction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 23915–23922 (2019).

Joya, K.S., Joya, Y.F. & de Groot, H.J.M. Ni-based electrocatalyst for water oxidation developed in-situ in a HCO3− /CO2 system at near-neutral pH. Adv. Energy Mater. 4, 3–7 (2014).

Chen, Z., Kang, P., Zhang, M.-T., Stoner, B.R. & Meyer, T.J. Cu(ii)/Cu(0) electrocatalyzed CO2 and H2O splitting. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 813 (2013).

Chen, Z. & Meyer, T.J. Copper(II) Catalysis of water oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 700–703 (2013).

Marcel Pourbaix. Atlas of Electrochemical Equilibria in Aqueous Solutions. (National Association of Corrosion Engineers, 1974).

Kanan, M.W., Surendranath, Y. & Nocera, D.G. Cobalt–phosphate oxygen-evolving compound. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 109–114 (2009).

Burke, L.D., Lyons, M.E. & Murphy, O.J. Formation of hydrous oxide films on cobalt under potential cycling conditions. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 132, 247–261 (1982).

Yu, M., Budiyanto, E. & Tüysüz, H. Principles of water electrolysis and recent progress in Cobalt-, Nickel-, and Iron-based oxides for the oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202103824 (2022).

Zhang, W., Cui, L. & Liu, J. Recent advances in cobalt-based electrocatalysts for hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. J. Alloy. Compd. 821, 153542 (2020).

Bergmann, A. et al. Reversible amorphization and the catalytically active state of crystalline Co3O4 during oxygen evolution. Nat. Commun. 6, 8625 (2015).

Wang, C., Deng, R., Guo, M. & Zhang, Q. Recent progress of advanced Co3O4-based materials for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction in acid: from rational screening to efficient design. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 31920–31942 (2023).

Cherevko, S. Stabilization of non-noble metal electrocatalysts for acidic oxygen evolution reaction. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 38, 101213 (2023).

Mondschein, J.S. et al. Crystalline Cobalt oxide films for sustained electrocatalytic oxygen evolution under strongly acidic conditions. Chem. Mater. 29, 950–957 (2017).

Natarajan, K., Munirathinam, E. & Yang, T.C.K. Operando investigation of structural and chemical origin of Co3O4stability in acid under oxygen evolution reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 27140–27148 (2021).

Krivina, R.A. et al. Anode catalysts in anion-exchange-membrane electrolysis without supporting electrolyte: conductivity, dynamics, and ionomer degradation. Adv. Mater. 34, 1–10 (2022).

Zhang, L., Xu, Q., Hu, Y., Chen, L. & Jiang, H. Benchmarking the pH–stability relationship of metal oxide anodes in anion exchange membrane water electrolysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 11, 13251–13259 (2023).

Wang, N. et al. Strong-Proton-adsorption co-based electrocatalysts achieve active and stable neutral seawater splitting. Adv. Mater. 35, 1–7 (2023).

Yan, Q. et al. Chromium-induced high covalent Co–O bonds for efficient anodic catalysts in PEM electrolyzer. Adv. Sci. 11, 1–8 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Tuning the Co pre-oxidation process of Co3O4 via geometrically reconstructed F–Co–O active sites for boosting acidic water oxidation. Energy Environ. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4EE03982C (2024).

Yu, P.C. et al. Nitrogen-mediated promotion of cobalt-based oxygen evolution catalyst for practical anion-exchange membrane electrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 20379–20390 (2024).

Faisal, F. et al. Atomically defined Co3O4 (111) thin films prepared in ultrahigh vacuum: stability under electrochemical conditions. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 7236–7248 (2018).

Chen, G.-Y. et al. Engineering cationic vacancies in octahedral sites of Co3O4 for high-efficiency oxygen evolution. Energy Fuels 37, 8523–8530 (2023).

Samu, A.A., Szenti, I., Kukovecz, A., Endrődi, B. & Janáky, C. Systematic screening of gas diffusion layers for high performance CO2 electrolysis. Commun. Chem. 6, 41 (2023).

Endrődi, B. et al. High carbonate ion conductance of a robust PiperION membrane allows industrial current density and conversion in a zero-gap carbon dioxide electrolyzer cell. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 4098–4105 (2020).

Di, Y. et al. Effect of urea and ammonium fluoride ratio on CuCo2S4 /NF as a highly efficient HER catalyst. RSC Adv. 13, 28713–28728 (2023).

Kiaeerad, P. & Naji, L. Synergistic effect of two complexing agents on the hydrothermal synthesis of self-supported ZnNiCo oxide as electrode material in supercapacitors. J. Electroanal. Chem. 901, 115779 (2021).

Adhikari, H. et al. Synthesis and electrochemical performance of hydrothermally synthesized Co3O4 nanostructured particles in presence of urea. J. Alloy. Compd. 708, 628–638 (2017).

Yetim, N.K. Hydrothermal synthesis of Co3O4 with different morphology: Investigation of magnetic and electrochemical properties. J. Mol. Struct. 1226, 129414 (2021).

Diallo, A., Beye, A.C., Doyle, T.B., Park, E. & Maaza, M. Green synthesis of Co3O4 nanoparticles via Aspalathus linearis: Physical properties. Green. Chem. Lett. Rev. 8, 30–36 (2015).

Biesinger, M.C. et al. Resolving surface chemical states in XPS analysis of first row transition metals, oxides and hydroxides: Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and. Ni. Appl. Surf. Sci. 257, 2717–2730 (2011).

Kang, W. et al. Unraveling sequential oxidation kinetics and determining roles of multi-cobalt active sites on Co3O4 catalyst for water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 3470–3477 (2023).

Samu, A.A. et al. Intermittent operation of CO2 electrolyzers at industrially relevant current densities. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 1859–1861 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Project no. RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00009, titled National Laboratory for Renewable Energy has been implemented with the support provided by the Recovery and Resilience Facility of the European Union within the framework of Programme Széchenyi Plan Plus. T.P. acknowledges the financial support of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. eChemicles Zrt acknowledges funding from the Hungarian NRDI Fund, through the 2021-1.1.4-GYORSÍTÓSÁV-2022-00029 project.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Szeged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.J., S.C., T. P., E.B. and A.K conceived the idea and designed the research. T.P. synthesized the catalyst samples used in this study. A.K. performed all the electrochemical measurements and analyzed the collected data. G.F.S. gathered and analyzed the XPS data. A. S. performed the SEM-EDX measurements. A. K. wrote the first version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to interpreting the results and revising the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

eChemicles is developing and commercializing CO2 electrolyzer systems.

Ethics

No humans or living organisms were subject of the study. In terms of research practices, all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kormányos, A., Priamushko, T., Samu, G.F. et al. Application of Co3O4 as anode catalyst in CO2 electrolyzer cells. NPG Asia Mater 17, 18 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00598-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00598-4